Abstract

Background

While changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover (BTM) have been reported to predict changes in bone mineral density (BMD), the relationship between changes in BMD and BTMs with combined antiresorptive/anabolic therapy is unknown.

Methods

In the DATA study, 94 postmenopausal osteoporotic women (ages 51–91) received either teriparatide 20-mcg SC daily, denosumab 60-mg SC every 6 months, or both for 2 years. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) were calculated to determine the relationship between baseline and early changes in BTMs (as well as serum sclerostin) and 2-year changes in BMD.

Results

In women receiving teriparatide, baseline BTMs did not correlate with 2-year BMD changes though 12-month increases in osteocalcin and P1NP were associated with 2-year increases in spine BMD. In women receiving denosumab, spine and hip BMD gains correlated with both baseline and changes in P1NP and C-telopeptide. In women receiving combined teriparatide/denosumab, while both baseline and decreases in P1NP were associated with spine BMD gains, distal radius increases were associated with less CTX suppression. Neither baseline nor changes in serum sclerostin correlated with BMD in any treatment group.

Summary and Conclusions

In women treated with teriparatide or denosumab, early BTM changes (increases and decreases, respectively) predict 2-year BMD gains, especially at the spine. In women treated with combined teriparatide/denosumab therapy, BMD increases at the distal radius were associated with less suppression of bone turnover. These results suggest that efficacy of combination therapy at cortical sites such as the radius may depend on residual bone remodeling despite RANKL inhibition.

Keywords: osteoporosis, bone resorption, bone turnover markers, denosumab, teriparatide, bone formation

Introduction

Assessing the response to osteoporosis therapy generally requires the serial measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) over 1–2 years. Because biochemical markers of osteoblast and osteoclast function change much more quickly in response to pharmacotherapy, however, it has been suggested that these measurements could be used to predict a patient’s response to therapy much earlier in the treatment course. In prior studies, both baseline and early changes in serum markers of bone turnover have been reported to predict the long-term BMD response in patients taking antiresorptive or anabolic therapy.1–4

In the Denosumab and Teriparatide Administration (DATA) study, we reported that the combination of teriparatide and denosumab increased BMD more than the individual agents.5,6 Whether baseline and early changes in serum markers of bone turnover can predict BMD changes in women who received the combination of denosumab and teriparatide is unknown. To determine whether these bone turnover marker changes can predict long-term BMD response, we now report the relationship between bone turnover markers and BMD in patients treated with combined denosumab and teriparatide, as well as each of the monotherapy treatment groups.

Methods

Details of the DATA and DATA-Switch study trial design and enrollment have been reported previously.5–7 The trial was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00926380). In brief, 94 postmenopausal osteoporotic women at high risk of fracture were randomized to receive teriparatide 20-mcg SC daily, denosumab 60-mg SC every 6 months, or both for 2 years. Women were considered at high risk for fracture if they had a spine or hip T-score of ≤−2.5; T-score of ≤−2.0 with at least one BMD-independent risk factor (fracture after age 50, parental hip fracture after age 50, prior hyperthyroidism, inability to rise from a chair with arms elevated, or current smoking); or T-score ≤−1.0 with a history of a fragility fracture. Women were excluded if they had ever taken parenteral bisphosphonates, teriparatide, or strontium ranelate, if they had taken glucocorticoids or oral bisphosphonates within 6 months of enrollment, or if they had taken estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, or calcitonin within 3 months of enrollment. Subjects were evaluated at 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Areal BMD by dual-energy absorptiometry (DXA) of the hip, spine, and 1/3 distal radius were measured at each visit.

Fasting morning samples were collected at each visit and collected 24 hours post injection, if receiving teriparatide. Serum osteocalcin (OC) was measured via electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD) with inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) of 10 and 8%, respectively. Serum aminoterminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP) was measured via radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland) with inter- and intra-assay CVs of 6–10 and 7–10%, respectively. Serum β-c terminal telopeptide of type one collagen (CTX) was measured via double-antibody ELISA (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with inter- and intra-assay CVs of 2–6 and 1–5%, respectively. Serum sclerostin was measured via an ELISA (Biomedica Gruppe, Wien, Austria) with inter- and intra-assay CVs of 5–7 and 4–6%, respectively. Serum samples were stored at −80C until the end of the study. For each marker, all blood samples from a subject were analyzed together in the same assay run after one thaw. The results of bone turnover markers at 0, 3, 6, and 12 months are reported here.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) were calculated to determine the relationship between bone turnover markers (at baseline and 3-, 6-, 12-month changes) and 24-month changes in BMD. Significance was determined by Fisher’s z-transformed normal approximation.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics, BMD, and bone turnover markers did not differ among the three treatment groups. Additionally, there were no differences in the incidence, duration, or time since discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates (table 1). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between subjects enrolled in the original DATA study and the 69 participants who completed the full 4-year protocol (who form the basis of this report).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all women who completed 48 months. Mean ± STD or %.

| Characteristic | Teriparatide (N=27) |

Denosumab (N=27) |

Combination (N=23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 66.1 ± 7.9 | 65.1 ± 6.2 | 65.3 ± 8.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.5 ± 3.7 | 23.8 ± 4.1 | 25.9 ± 5.2 |

| Percent White, Non-Hispanic | 100% | 89% | 87% |

| HISTORY OF FRACTURE (%) | 52% | 37% | 35% |

| Previous BP use (%) | 44% | 33% | 39% |

| Duration of use (months) | 45 ± 23 | 45 ± 26 | 25 ± 21 |

| Time since discontinuation (months) | 27 ± 20 | 35 ± 24 | 41 ± 18 |

| 25-OH vitamin D (ng/mL) | 32.2 ± 8.5 | 35.9 ± 11.0 | 34.8 ± 12.8 |

| Osteocalcin (ng/mL) | 46.3 ± 26.1 | 43.9 ± 20.2 | 55.0 ± 32.6 |

| P1NP (ug/L) | 54.1 ± 21.9 | 52.7 ± 19.5 | 61.7 ± 20.6 |

| β-CTX (ng/mL) | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Sclerostin (pg/mL) | 801 ± 327 | 797 ± 376 | 863 ± 456 |

Changes in bone mineral density and bone turnover markers

As previously described, BMD increased over 24-months in all three treatment groups at the hip and spine, with the largest increases observed in the combination therapy group (table 2).5 BMD increased similarly at the distal 1/3 radius in the denosumab and combination groups but decreased in the teriparatide group. Figures 1 and 2 show the changes in bone turnover markers and sclerostin over 12-months. In women treated with teriparatide, mean serum OC, P1NP, and CTX increased significantly at all time points whereas they decreased at nearly all time points in the other two groups. In the teriparatide group, the increase in these markers appeared to peak between months 6–12. In the denosumab group, serum OC, P1NP, and CTX decreased by month 3 and remained suppressed through month 12. In the women treated with combination denosumab and teriparatide, serum OC decreased by month 6 whereas serum P1NP and serum CTX decreased by month 3. All three markers remained suppressed at month 12. In all three treatment groups, serum sclerostin increased at 3-months, peaked at 6-months, and remained increased at 12-months (with no between group differences).

Table 2.

Two-year increases (Mean ± STD) in bone mineral density at posterior-anterior spine, femoral neck, total hip, and 1/3 distal radius of all women who completed 48 months.

| Skeletal site | Teriparatide (N=27) |

Denosumab (N=27) |

Combination (N=23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA Spine BMD | 9.5 ± 5.9%# | 8.3 ± 3.4%# | 12.9 ± 5.0# * |

| Femoral neck BMD | 2.8 ± 3.9%# | 4.1 ± 3.8%# | 6.8 ± 3.6%# * |

| Total Hip BMD | 2.0 ± 3.0%# | 3.2 ± 2.5%# | 6.3 ± 2.6%# * |

| 1/3 Radius BMD | −1.7 ± 4.6% | 2.1 ± 3.1%# | 2.2 ± 3.1%# * |

p<0.01 vs baseline,

p<0.01 vs other groups.

Figure 1.

Mean (SEM) percent change in bone turnover markers A. Teriparatide B. Denosumab alone and teriparatide and denosumab combined. Data for teriparatide-alone group are shown separately for clarity. *p<0.05 vs. baseline. a p<0.001 vs denosumab and vs combined therapy. b p<0.01 vs denosumab. TPTD=teriparatide. DMAB=denosumab.

Figure 2.

Mean (SEM) percent change in serum sclerostin. P<0.05 at all timepoints for all groups versus baseline.

Associations between bone mineral density and bone turnover markers

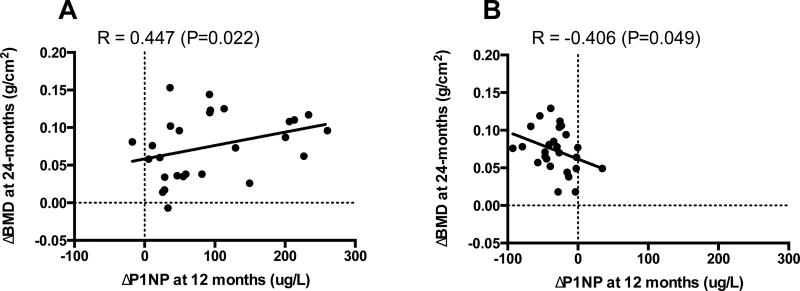

The correlations between baseline levels and change in bone turnover markers with 24-month changes in BMD are shown in Table 3. In women who received teriparatide, baseline levels of OC, P1NP, and CTX did not correlate with 24-month BMD changes at any site. The percent increase in serum OC at 12 months was associated with the increase in spine BMD at 24 months (R=0.428, P=0.029) but not at other sites. The 24-month increases in spine BMD also correlated with the increase in P1NP at months 6 and 12 (Fig 3). Changes in CTX did not correlate with change in BMD at any site. The increase in serum sclerostin at 6 months was inversely associated with the 24-month increase in BMD at the femoral neck but not at other sites (table 4).

Table 3.

Correlations (R) between bone turnover markers and 24 month change in BMD by treatment group.

| TPTD | P1NP at baseline | P1NP at 3mo | P1NP at 6mo | P1NP at 12mo | OC at baseline | OC at 3mo | OC at 6mo | OC at 12mo | CTX at baseline | CTX at 3mo | CTX at 6mo | CTX at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | 0.187 | 0.367 | 0.472* | 0.447* | 0.186 | 0.320 | 0.238 | 0.428* | 0.154 | 0.174 | 0.387 | 0.346 |

| Total hip | 0.028 | 0.109 | 0.290 | 0.116 | 0.039 | 0.023 | 0.228 | 0.343 | 0.043 | −0.283 | 0.172 | 0.172 |

| Femoral neck | 0.141 | 0.149 | 0.233 | 0.091 | 0.102 | 0.031 | −0.015 | 0.138 | −0.062 | 0.068 | 0.154 | 0.068 |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.110 | −0.066 | −0.182 | −0.334 | 0.062 | 0.015 | 0.188 | −0.282 | 0.026 | −0.077 | −0.222 | −0.077 |

| DMAB | P1NP at baseline | P1NP at 3mo | P1NP at 6mo | P1NP at 12mo | OC at baseline | OC at 3mo | OC at 6mo | OC at 12mo | CTX at baseline | CTX at 3mo | CTX at 6mo | CTX at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | 0.583* | −0.514* | −0.554* | −0.406* | 0.462* | −0.460* | −0.455* | −0.468* | 0.509* | −0.462* | −0.465* | −0.445* |

| Total hip | 0.549* | −0.678* | −0.589* | −0.373 | 0.410 | −0.463* | −0.364 | −0.391 | 0.457* | −0.569* | −0.501* | −0.517* |

| Femoral neck | 0.039 | −0.022 | 0.022 | 0.172 | 0.258 | −0.018 | −0.159 | −0.233 | 0.302 | −0.295 | −0.305 | −0.361 |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.116 | −0.078 | −0.153 | −0.233 | 0.206 | −0.129 | −0.170 | −0.110 | −0.154 | 0.140 | 0.045 | 0.132 |

| COMBO | P1NP at baseline | P1NP at 3mo | P1NP at 6mo | P1NP at 12mo | OC at baseline | OC at 3mo | OC at 6mo | OC at 12mo | CTX at baseline | CTX at 3mo | CTX at 6mo | CTX at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | 0.592* | −0.515* | −0.584* | −0.527* | −0.016 | −0.016 | −0.076 | −0.080 | 0.010 | −0.046 | −0.104 | −0.068 |

| Total hip | 0.357 | −0.274 | −0.268 | −0.317 | 0.395 | −0.121 | −0.261 | −0.316 | 0.341 | −0.328 | −0.262 | −0.271 |

| Femoral neck | −0.175 | 0.203 | 0.270 | 0.174 | 0.428 | −0.193 | −0.322 | −0.318 | 0.275 | −0.264 | −0.186 | −0.213 |

| 1/3 Radius | −0.037 | 0.152 | 0.043 | −0.028 | −0.093 | 0.442 | 0.222 | 0.054 | −0.452 | 0.470* | 0.449 | 0.525* |

p value <0.05

Figure 3.

12-month change in P1NP correlated to spine BMD change in women who received teriparatide (A) or denosumab (B).

Table 4.

Correlations (R) between serum sclerostin and 24 month change in BMD by treatment group.

| TPTD | Sclerostin at baseline | Sclerostin at 3mo | Sclerostin at 6mo | Sclerostin at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | 0.122 | −0.026 | −0.073 | 0.181 |

| Total hip | −0.070 | −0.254 | −0.146 | 0.082 |

| Femoral neck | 0.139 | −0.294 | −0.453* | −0.321 |

| 1/3 Radius | −0.414 | −0.257 | −0.121 | −0.285 |

| DMAB | Sclerostin at baseline | Sclerostin at 3mo | Sclerostin at 6mo | Sclerostin at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | −0.261 | −0.112 | −0.056 | 0.229 |

| Total hip | 0.313 | 0.010 | 0.249 | −0.004 |

| Femoral neck | 0.054 | −0.125 | −0.153 | −0.211 |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.161 | 0.011 | 0.132 | 0.192 |

| COMBO | Sclerostin at baseline | Sclerostin at 3mo | Sclerostin at 6mo | Sclerostin at 12mo |

| Lumbar spine | −0.093 | −0.059 | −0.077 | −0.370 |

| Total hip | −0.176 | 0.309 | −0.261 | −0.276 |

| Femoral neck | −0.029 | −0.030 | −0.095 | −0.121 |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.065 | −0.022 | 0.171 | 0.121 |

p value <0.05

In women who received denosumab, higher baseline levels of OC, P1NP, and CTX were associated with greater increases in BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip (table 3). OC, P1NP, and CTX decreases at 3-, 6-, and 12-months were also associated with greater increases in BMD, particularly at the spine (Fig 3). Baseline and early changes in serum sclerostin did not correlate with change in BMD at any site.

In women who received both denosumab and teriparatide, higher baseline levels of P1NP were associated with greater increases in BMD at the lumbar spine (table 3). Decreases in P1NP at each time point were also associated with increases in BMD at the spine. The relationship between changes in distal radius BMD and bone turnover, however, demonstrated a different pattern (Fig 4). Specifically, in women treated with combination therapy, the 3 and 12-month changes in CTX were positively associated with the 24-month increase in distal radius BMD (that is to say that less suppression of CTX was associated with a larger increase in distal radius BMD) (R=0.470, P=0.049; R=0.525, P=0.025, respectively). There was also a trend toward an association between the 3-month change in OC and the increase in radius BMD (R= 0.442, P=0.074). Baseline and early changes in serum sclerostin did not correlate with change in BMD at any site.

Figure 4.

Change in CTX correlated to 1/3 radius BMD change in women who received combination denosumab and teriparatide.

Discussion

In postmenopausal osteoporotic women treated with either teriparatide or denosumab, early changes in bone turnover markers (increases and decreases, respectively) predicted 2-year BMD gains, especially at the spine. In women treated with combination therapy, less suppression of bone resorption was associated with greater BMD gains at the radius whereas more suppression of P1NP correlated with greater BMD gains at the spine.

The observed positive correlations between BMD gains and markers of bone remodeling in women treated with teriparatide are similar to results reported in prior studies. In the 541 postmenopausal women who received teriparatide 20-mcg daily in the Fracture Prevention Trial, baseline values and 3-month increases in P1NP were associated with 18-month increases in spine BMD. Additionally, baseline urine NTX levels correlated with 18-month increases in spine BMD and 12-month increases in hip BMD.1 Similarly, in the European Study of Forsteo (EURFORS), baseline and early changes in P1NP were associated with 24-month increases in BMD at the spine and hip.2 Finally, in a separate study of 207 men and postmenopausal women treated with teriparatide 20-mcg daily for 12 months, baseline levels and 1-month increases in P1NP were positively associated with both spine and hip BMD changes, as were baseline CTX concentrations.3

Denosumab potently suppresses bone resorption and formation and our current results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that the levels of bone turnover suppression correlate with the subsequent increase in BMD.4 In contrast to teriparatide, in which bone turnover markers correlated primarily with spine BMD, early changes in bone turnover markers are associated with both hip and spine BMD in patients treated with denosumab. In the FREEDOM Trial substudy of 160 postmenopausal osteoporotic women, for example, both the 6-month decrease in CTX and 6-month decrease in P1NP were associated with the 36-month increase in BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip.4

Correlations between changes in bone turnover markers and BMD have not previously been reported in patients receiving combined anabolic/antiresorptive therapy. In the current study, higher baseline P1NP levels, but not CTX levels, were associated with spine BMD gains in patients receiving both denosumab and teriparatide. This finding lies in contrast to the significant CTX-BMD relationship observed in the denosumab group. Notably, while the relationships between CTX and BMD differ between the denosumab monotherapy and combination groups, the actual changes in CTX in the two groups were identical over the entire 2-year treatment period. The mechanisms underlying these distinct relationships are unclear. One possible explanation is that BMD increases in women receiving combination therapy (but not denosumab monotherapy) are partially independent of bone resorption (i.e. modeling-based), as we have hypothesized previously.5,6 That said, it is also notable that in women treated with both teriparatide and denosumab, less suppression of bone resorption was associated with greater increases in distal radius BMD. This finding may suggest that some ongoing bone resorption does play an important role in combination therapy’s efficacy in cortical bone.

In the current study, we report that serum sclerostin, an osteocyte-derived Wnt signaling inhibitor, increased in all three treatment groups. Sclerostin is an antagonist of the Wnt pathway and therefore a negative regulator of osteoblast differentiation and proliferation and hence bone formation.8 In animals, SOST expression has been shown to decrease in response to continuous or intermittent PTH, suggesting that sclerostin may in part mediate the anabolic effect of PTH.9,10 Studies investigating the serum sclerostin response to PTH in humans, however, have not been consistent. For example, our group previously reported that serum sclerostin levels and bone formation markers acutely decreased in men during an 18-hour PTH infusion, though in a separate study of 10 postmenopausal women previously treated with bisphosphonates, no acute changes in serum sclerostin were observed 2, 4, or 24-hours after injections of either PTH-1-84 100-mcg or PTH-1-34 20-mcg.11,12 Conversely, in 25 postmenopausal osteoporotic women treated with a single 40-mcg SC dose of teriparatide, mean serum sclerostin increased 4 hours after administration.13

Studies investigating the longer-term effects of PTH on serum sclerostin levels have also reported conflicting results. For example, in men and women with osteoporosis who received 40-mcg teriparatide daily for 24 months, serum sclerostin levels (measured 24-hours post injection) increased with a peak at 3 months followed by reversion towards baseline at 18 months (with no association with BMD).14 There was also no change in serum sclerostin in postmenopausal osteoporotic women who received 6 or 12 months of teriparatide or in women with anorexia nervosa after 18 months of teriparatide.15–18 However, in another study of 27 postmenopausal women who received daily teriparatide, serum sclerostin decreased at 9 months though failed to reach significant difference at months 12 and 18.19 Similarly, in postmenopausal women who received teriparatide 40-mcg SC for 14 days, serum sclerostin drawn 4-hours post teriparatide injection decreased.20 The increase in serum sclerostin observed in the denosumab group in the present study is consistent with most, but not all, prior reports in women treated with antiresorptive agents. Specifically, serum sclerostin has been reported to increase when measured 3, 6, and 12-months post denosumab injection.17,21,22 Conversely, in women who were previously treated with zoledronic acid, there was no change in serum sclerostin after 1 year of denosumab.23 Finally, the increase in serum sclerostin we observed in women receiving combination therapy is consistent with a recent study in which teriparatide therapy was started after three months of denosumab exposure and continued for an additional 9-months.17

The lack of consistency in these reports of serum sclerostin changes in response to teriparatide may suggest that sclerostin does not play a major role in the mechanism underlying PTH’s osteoanabolic effects. Alternatively, while bone marrow plasma and peripheral blood serum sclerostin concentrations have been reported to correlate, the significance of circulating levels of sclerostin in relation to the local sclerostin expression may be minimal.20 Additionally, measurement of peripheral sclerostin is not yet standardized and differences in study results may reflect the various methodologies. The currently available commercial assays may recognize different epitopes and the clinical significance of measuring sclerostin as intact or in fragments is unknown.24

A potential limitation of the current study is that some participants received bisphosphonates prior to enrollment. However, baseline levels of bone turnover markers were similar among the three groups and analysis of subjects with or without a history of bisphosphonate use showed a similar pattern to the entire cohort (data not shown). Additionally, we recognize that our utilization of an uncorrected statistical analysis despite multiple comparisons, along with DATA’s relatively small sample size, limits the definitiveness of our conclusions and may be best understood as hypothesis generating.

In summary, this analysis demonstrates that in women treated with teriparatide or denosumab, early changes in bone turnover markers (increases and decreases, respectively) predicted 2-year increases in BMD, particularly at the lumbar spine. In women treated with combination therapy, however, a more complex relationship may exist wherein changes in bone resorption are not associated with spine or hip BMD while radius BMD gains are at least partially dependent on higher levels of residual bone remodeling. These early changes in bone resorption may be helpful to predict 2-year changes in the distal radius. Further studies, including those that include direct histomorphometric analysis, are now required to better define the relationship between bone remodeling, bone formation, and bone mass accrual in women treated with combined antiresorptive and anabolic agents.

Highlights.

With teriparatide, early increases in BTM were generally associated with BMD increase.

With denosumab, early decreases in BTM were generally associated with BMD increases.

With combo therapy, the BTM-BMD relationship was generally similar to denosumab.

With combo therapy at the radius, BMD gains were associated with less CTX suppression.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study volunteers for their participation. This work is supported by NIH/NIAMS grant K23AR068447 (to JNT), NIH/NIAMS grant K24AR067847 (to BZL), Eli Lilly, and Amgen. Eli Lilly and Amgen did not have any role in study design, data analysis, or data interpretation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: JNT, SMB, and HL have nothing to declare. BZL is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Amgen Inc, and Merck.

References

- 1.Chen P, Satterwhite JH, Licata AA, Lewiecki EM, Sipos AA, Misurski DM, Wagman RB. Early changes in biochemical markers of bone formation predict BMD response to teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20:962–70. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumsohn A, Marin F, Nickelsen T, Brixen K, Sigurdsson G, Gonzalez de la Vera J, Boonen S, Liu-Leage S, Barker C, Eastell R, Group ES. Early changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover and their relationship with bone mineral density changes after 24 months of treatment with teriparatide. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2011;22:1935–46. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1379-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsujimoto M, Chen P, Miyauchi A, Sowa H, Krege JH. PINP as an aid for monitoring patients treated with teriparatide. Bone. 2011;48:798–803. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastell R, Christiansen C, Grauer A, Kutilek S, Libanati C, McClung MR, Reid IR, Resch H, Siris E, Uebelhart D, Wang A, Weryha G, Cummings SR. Effects of denosumab on bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26:530–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leder BZ, Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, Burnett-Bowie SA, Zhu Y, Foley K, Lee H, Neer RM. Two years of Denosumab and teriparatide administration in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (The DATA Extension Study): a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99:1694–700. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, Lee H, Kumbhani R, Siwila-Sackman E, McKay EA, Burnett-Bowie SA, Neer RM, Leder BZ. Teriparatide and denosumab, alone or combined, in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: the DATA study randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:50–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leder BZ, Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, Wallace PM, Lee H, Neer RM, Burnett-Bowie SA. Denosumab and teriparatide transitions in postmenopausal osteoporosis (the DATA-Switch study): extension of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1147–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semenov M, Tamai K, He X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:26770–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellido T, Ali AA, Gubrij I, Plotkin LI, Fu Q, O'Brien CA, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Chronic elevation of parathyroid hormone in mice reduces expression of sclerostin by osteocytes: a novel mechanism for hormonal control of osteoblastogenesis. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4577–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keller H, Kneissel M. SOST is a target gene for PTH in bone. Bone. 2005;37:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piemonte S, Romagnoli E, Bratengeier C, Woloszczuk W, Tancredi A, Pepe J, Cipriani C, Minisola S. Serum sclerostin levels decline in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis following treatment with intermittent parathyroid hormone. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2012;35:866–8. doi: 10.3275/8522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu EW, Kumbhani R, Siwila-Sackman E, Leder BZ. Acute decline in serum sclerostin in response to PTH infusion in healthy men. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96:E1848–51. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai JN, Leder BZ. Immediate Effects of Intermittent Parathyroid Hormone on Circulating Sclerostin Levels. Endocrine Society. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu EW, Schindler E, Wyland JJ, Neer RM, Finkelstein JS. Change in Serum Sclerostin after 24 months of Teriparatide or Alendronate. American Society of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polyzos SA, Anastasilakis AD, Bratengeier C, Woloszczuk W, Papatheodorou A, Terpos E. Serum sclerostin levels positively correlate with lumbar spinal bone mineral density in postmenopausal women--the six-month effect of risedronate and teriparatide. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2012;23:1171–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatti D, Viapiana O, Idolazzi L, Fracassi E, Rossini M, Adami S. The waning of teriparatide effect on bone formation markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis is associated with increasing serum levels of DKK1. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96:1555–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idolazzi L, Rossini M, Viapiana O, Braga V, Fassio A, Benini C, Kunnathully V, Adami S, Gatti D. Teriparatide and denosumab combination therapy and skeletal metabolism. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3647-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fazeli PK, Wang IS, Miller KK, Herzog DB, Misra M, Lee H, Finkelstein JS, Bouxsein ML, Klibanski A. Teriparatide increases bone formation and bone mineral density in adult women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99:1322–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sridharan M, Cheung J, Moore AE, Frost ML, Fraser WD, Fogelman I, Hampson G. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 increases following intermittent parathyroid hormone (1–34) in postmenopausal osteoporosis: association with biomarker of bone formation. Calcified tissue international. 2010;87:398–405. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drake MT, Srinivasan B, Modder UI, Peterson JM, McCready LK, Riggs BL, Dwyer D, Stolina M, Kostenuik P, Khosla S. Effects of parathyroid hormone treatment on circulating sclerostin levels in postmenopausal women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95:5056–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Gkiomisi A, Bisbinas I, Gerou S, Makras P. Comparative effect of zoledronic acid versus denosumab on serum sclerostin and dickkopf-1 levels of naive postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, head-to-head clinical trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:3206–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatti D, Viapiana O, Fracassi E, Idolazzi L, Dartizio C, Povino MR, Adami S, Rossini M. Sclerostin and DKK1 in postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with denosumab. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27:2259–63. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anastasilakis AD, Polyzos SA, Gkiomisi A, Saridakis ZG, Digkas D, Bisbinas I, Sakellariou GT, Papatheodorou A, Kokkoris P, Makras P. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients previously treated with zoledronic acid. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2015;26:2521–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke BL, Drake MT. Clinical utility of serum sclerostin measurements. BoneKEy reports. 2013;2:361. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]