Summary

The mitochondrial proteome is built mainly by import of nuclear-encoded precursors, which are targeted mostly by cleavable presequences. Presequence processing upon import is essential for proteostasis and survival, but the consequences of dysfunctional protein maturation are unknown. We find that impaired presequence processing causes accumulation of precursors inside mitochondria that form aggregates, which escape degradation and unexpectedly do not cause cell death. Instead, cells survive via activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR)-like pathway that is triggered very early after precursor accumulation. In contrast to classical stress pathways, this immediate response maintains mitochondrial protein import, membrane potential, and translation through translocation of the nuclear HMG-box transcription factor Rox1 to mitochondria. Rox1 binds mtDNA and performs a TFAM-like function pivotal for transcription and translation. Induction of early mtUPR provides a reversible stress model to mechanistically dissect the initial steps in mtUPR pathways with the stressTFAM Rox1 as the first line of defense.

Keywords: mitochondrial protein import, presequence processing, unfolded protein response, mitochondria-nuclear communication, proteostasis, proteotoxic, stress response

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Impaired presequence processing leads to precursor aggregation inside mitochondria

-

•

Intramitochondrial precursor aggregates trigger early transcriptional stress response

-

•

Relocalization of nuclear transcription factor Rox1 to mitochondria ensures survival

-

•

Mitochondrial Rox1 maintains mitochondrial genome expression upon early mtUPR

N-terminal presequences direct cytosolic precursor proteins to mitochondria. Poveda-Huertes et al. show that impaired presequence cleavage leads to proteotoxic aggregates inside mitochondria that trigger an early mtUPR-like stress response. Relocalization of the nuclear transcription factor Rox1 to mitochondria allows maintenance of mtDNA expression ensuring proteostasis and survival upon early mtUPR.

Introduction

A key event in the evolution of mitochondria was the establishment of protein import that allowed gene transfer from the organelle to the nucleus (Chacinska et al., 2009, Neupert and Herrmann, 2007, Nunnari and Suomalainen, 2012, Schulz et al., 2015). This was accompanied by the development of presequences, N-terminal extensions that are present in approximately 70% of all mitochondrial precursor proteins (Burkhart et al., 2015, Mani et al., 2016, Quirós et al., 2015, Teixeira and Glaser, 2013, Vögtle et al., 2009, Vögtle et al., 2018). These presequences allow a cytosolic precursor protein to enter the organelle (via the translocase of the outer membrane [TOM]). Translocation is followed by sorting to the respective subcompartment via the presequence pathway, including the main translocase of the inner membrane (TIM23) and the presequence translocase-associated import motor (PAM) (Chacinska et al., 2009, Endo and Yamano, 2009, Harbauer et al., 2014, Neupert and Herrmann, 2007, Schulz et al., 2015). In parallel, a proteolytic system evolved that removes the presequences upon entry into the mitochondrial matrix (Burkhart et al., 2015, Teixeira and Glaser, 2013, Vögtle et al., 2009, Vögtle et al., 2018). This import process is assisted by a dedicated chaperone network in the matrix, including Hsp70 complexes that mediate the terminal import reaction and together with Hsp60/Hsp10 complexes ensure proper folding of the mature proteins (Balchin et al., 2016, Chacinska et al., 2009, Neupert and Herrmann, 2007).

The main mitochondrial presequence protease MPP is composed of two subunits (Mas1 and Mas2 in yeast, PMPCB and PMPCA in human). The genes encoding for these two subunits are essential for life, and point mutations in the catalytic subunit PMPCB result in severe neurodegeneration and death in childhood in human patients (Vögtle et al., 2018). However, the detrimental molecular and cellular consequences upon impaired presequence processing have not yet been investigated.

Results

Accumulation of Aggregation-Prone Precursor Proteins inside Mitochondria Causes a Transcriptional Stress Response

To analyze the downstream events of impaired precursor processing we used a yeast strain with a temperature-sensitive allele of the catalytic MPP subunit Mas1 (mas1ts) that allows to turn off MPP activity at higher temperature (Figure S1A; Burkhart et al., 2015, Vögtle et al., 2009, Vögtle et al., 2018). As a long-standing paradigm in the field, non-processed precursor proteins were thought to be less stable and rapidly degraded, while removal of the presequence enables maturation of stable, functional proteins (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2007, Teixeira and Glaser, 2013). We systematically profiled isolated mitochondria from wild-type and mas1ts strains, grown under permissive and non-permissive respiratory conditions and first tested if impaired MPP activity has an impact on organellar proteome stability. We lysed mitochondria in non-ionic detergent followed by centrifugation and analyzed supernatant and pellet fractions. We found an unexpected large amount of proteins in the non-soluble pellet fraction specifically in the mas1ts sample in which MPP function was turned off during cell growth for 10 h at 37°C (Figure 1A). Analysis of individual mitochondrial proteins by western blotting revealed that all MPP-dependent proteins tested accumulated as non-processed precursor proteins in the non-soluble pellet fraction (Figure 1B). Their fully processed (and partially reduced) mature forms were predominantly extracted to the soluble fraction (Figure 1B) like MPP-independent proteins (Figure 1C). Under permissive conditions mature proteins of all classes were equally abundant and present in the soluble fraction in wild-type and mas1ts samples (Figures S1B and S1C). Accumulation of immature precursor proteins in the insoluble pellet fraction led us to speculate that defective precursor processing may lead to protein aggregates inside mitochondria that could not be cleared by organellar proteolysis and might be proteotoxic. Indeed, electron microscopy revealed specific accumulation of electron densities, likely reflecting protein aggregates in mas1ts mitochondria (non-permissive conditions; Figures S1D and S1E), while precursor protein import into mitochondria was not compromised (Figure S1F). Moreover, degradation of non-processed precursor proteins was severely inhibited compared with the degradation rate of mature mitochondrial proteins (Figure 1D), while overall degradation capacity in mas1ts mitochondria was not affected (Figure S1G), implying the necessity of a functional presequence processing machinery for balanced organellar protein turnover. We then asked if the aggregation of non-processed precursor proteins inside mitochondria may require a certain level of pre-existing aggregates or if this occurs de novo (i.e., directly upon precursor protein import into the matrix). We tested this by importing radiolabeled MPP substrate precursor proteins (Cox4 and Mdh1) into isolated mitochondria from wild-type and mas1ts strains grown under permissive growth conditions (i.e., without compromised MPP activity; Figures S1A and S1B). In organello heat shock for 15 min (37°C) leads to MPP inactivation and consequently impaired processing of freshly imported precursor proteins (Vögtle et al., 2018). Testing of the solubility of imported precursor proteins revealed their immediate aggregation in mas1ts mitochondria, indicating that the predisposition for aggregation is intrinsic and independent of pre-existing protein aggregates (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Non-processed Precursor Proteins Form Aggregates inside Mitochondria and Escape Organellar Degradation

(A) Coomassie-stained gels from SDS-PAGE of wild-type (WT) and mas1ts mitochondria isolated from cells grown under respiratory conditions and separated into soluble (SN [supernatant]) and aggregated (P [pellet]) protein fractions.

(B) Immunoblots of samples from (A) analyzed with antisera against indicated MPP substrate proteins. i, processing intermediate; m, mature; p, precursor.

(C) Immunoblots of samples from (A) analyzed with antisera against non-processed proteins.

(D) In organello degradation of indicated precursor (p) and mature (m) forms of Cox4, Rip1, and Isu1 in mas1ts mitochondria. i, processing intermediate; Om45 and Tom70, non-processed control proteins.

(E) Import of radiolabeled precursor proteins into isolated WT or mas1ts mitochondria followed by separation into soluble (SN) and aggregated protein (P) fraction. T, total, non-lysed mitochondria. Where indicated the membrane potential (Δψ) was depleted prior to the import reaction.

See also Figure S1.

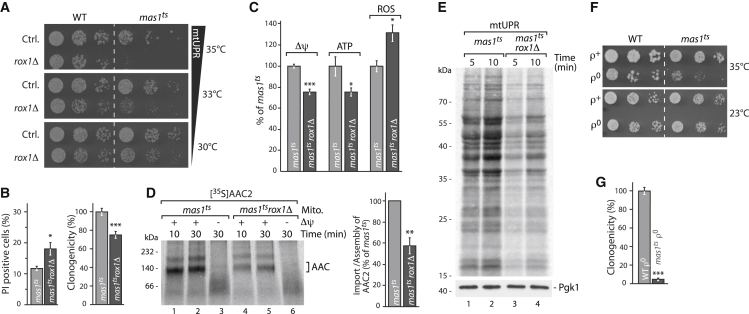

Our finding that impaired presequence processing leads to matrix-localized protein aggregates that escape organellar degradation may explain why this process is essential for eukaryotic cells. We tested for cell viability upon induction of MPP impairment and observed that mas1ts cells survive comparably with wild-type cells (Figures 2A and 2B). Thus, rather unexpectedly, MPP dysfunction and concomitant accumulation of protein aggregates within mitochondria do not trigger cell death. We also noticed that the matrix heat shock protein Hsp10, a component of the mitochondrial GroEL complex and a typical marker of mitochondrial stress responses (Shpilka and Haynes, 2018, Nargund et al., 2012, Quirós et al., 2016, Ryan and Hoogenraad, 2007), is dramatically increased in mas1ts mitochondria (Figure 1C). This led us to the speculation that the increase in Hsp10 might be the consequence of a stress-like response preventing death upon dysfunctional presequence processing. We searched for the minimal induction time of mas1ts for intramitochondrial protein aggregation and found initial accumulation of non-processed precursor proteins already after 2 h (Figure 2C). We wondered if such short induction of intramitochondrial protein aggregation might cause a cellular compensatory response and performed global transcriptional profiling after 2 and 4 h of MPP impairment. While permissive condition (growth at 23°C) did not affect global transcript profiles, the 2 h induction led to upregulation of 180 and downregulation of 205 genes (Figures 2D and S2A; Table S1), indicating a massive transcriptional response upon short-term MPP inactivation (after 4 h induction, the number of deregulated transcripts decreased again; Figure S2A). We wondered if this response could represent a mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR)-like pathway that is among other features characterized by transcriptional changes in chaperone and protease genes. Indeed, many of the upregulated genes in our transcriptional profiling encoded subunits from protein folding/refolding networks within the mitochondrial matrix and the cytosol (Figures 2E and S2B). Several of the mitochondrial folding/refolding proteins, such as Hsp78, the Lon protease Pim1, and the co-chaperone Mdj1, were described to be involved in the classical mtUPR pathways. Indeed, lack of these proteins resulted in a severe growth defect upon MPP impairment (Figure S2C). Next, we assessed further typical characteristics of mtUPR and other mitochondrial stress response pathways, such as stalling of cytosolic and mitochondrial translation, transcriptional activation of the protein import machinery and proteasome assembly, increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Eisenberg-Bord and Schuldiner, 2017, Shpilka and Haynes, 2018, Münch and Harper, 2016, Nargund et al., 2012, Quirós et al., 2016, Taylor et al., 2014, Wrobel et al., 2015). However, unexpectedly, none of these parameters were changed upon induction of intramitochondrial precursor aggregation in the mas1ts cells (Figures S3A–S3F). This classifies this particular immediate stress response as unique, and it might represent the earliest step in classical mtUPR pathways identified so far. The reversible inactivation of MPP will now allow dissection of the long-sought initiation mechanisms of such mitochondrial stress pathways.

Figure 2.

Accumulation of Aggregation-Prone Precursor Proteins inside Mitochondria Causes a Transcriptional Stress Response

(A) Cell death determined by flow cytometric quantification of propidium iodide (PI) staining indicative of loss of plasma membrane integrity of wild-type (WT) and mas1ts cells after shift to 37°C for indicated time. n = 12; data represent mean ± SEM; n.s., not significant.

(B) Determination of clonogenicity via survival plating of WT and mas1ts cells after shift to 37°C for the indicated time. n = 6; data represent mean ± SEM.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of WT and mas1ts mitochondria isolated from strains shifted for indicated times to non-permissive temperature. Sod2preseq., antibody generated against presequence peptide of Sod2.

(D) Distribution of transcripts quantified by RNA-seq in WT and mas1ts cells. Displayed are Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p values. FDR, false discovery rate.

(E) Highlighted transcripts analyzed in (D) for indicated Gene Ontology (GO) terms provided by Saccharomyces Genome Database.

The Nuclear Transcription Factor Rox1 Is a Mediator of the Early mtUPR Pathway

To identify mediators of such an early mtUPR, we profiled 30 transcription factors for synthetic lethality with mas1ts upon MPP dysfunction (Figures S4A–S4C; STAR Methods). We identified one candidate, Rox1, whose presence is required for cell growth and viability upon mtUPR but was dispensable for wild-type cells (Figures 3A, 3B, and S3G–S3I). Rox1 belongs to a highly conserved nuclear HMG-box domain containing transcription factor family and is reported to act as a repressor of several genes upon hypoxia in yeast (Liu and Barrientos, 2013). In the absence of Rox1, already mild mtUPR caused a decline in the membrane potential (Δψ) and mitochondrial ATP levels, as well as an increase of mitochondrial ROS in the mas1 mutant cells (Figures 3C, S3J, and S3K). We also observed severe impairment of protein import activity (Figure 3D; shown for the ADP/ATP carrier precursor protein Aac2/Pet9) and cytosolic translation (Figure 3E). Both are likely consequences of decreased Δψ and elevated ROS, respectively (Topf et al., 2018). Thus, the presence of Rox1 is required for protecting mitochondrial and cellular integrity against intramitochondrial proteotoxic aggregates. In contrast, Rox1 absence leads to the typical characteristics (Eisenberg-Bord and Schuldiner, 2017, Shpilka and Haynes, 2018, Münch and Harper, 2016, Nargund et al., 2012, Quirós et al., 2016, Ryan and Hoogenraad, 2007, Taylor et al., 2014, Wrobel et al., 2015) described in the previously reported various mtUPR pathways. Our observation that lack of Rox1 induces these deteriorations upon mtUPR indicates that Rox1 may mediate a very early and probably common step in mitochondrial stress response pathways.

Figure 3.

Identification of Rox1 as a Mediator of the Early Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response (mtUPR) Pathway

(A) Synthetic growth defect in mas1tsrox1Δ mutant at indicated temperatures on respiratory (YPglycerol) conditions.

(B) Determination of cell death via PI staining and of clonogenic survival via survival plating in mas1ts and mas1tsrox1Δ cells (12 h induction). n = 4 for PI staining and n = 6 for clonogenic survival; data represent mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(C) Measurements of Δψ, ATP levels and ROS in mas1ts and mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria (Δψ, ATP level 10 h, ROS 4 h induction). n = 3; data represent mean ± SEM.

(D) Blue native PAGE autoradiography of assembled AAC2 complex after import into isolated mas1ts and mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria. Quantification for n = 3; data represent mean ± SEM.

(E) SDS-PAGE autoradiography analysis of cytosolic translation activity in mas1ts and mas1tsrox1Δ cells (4 h induction). Pgk1, cytosolic marker as loading control.

(F) Growth of rho+ (ρ+) and rho0 (ρ0) WT and mas1ts cells on YPglucose plates at indicated temperature.

(G) Determination of clonogenicity via survival plating of WT rho0 (ρ0) and mas1ts rho0 (ρ0) cells. n = 8; data represent mean ± SEM.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

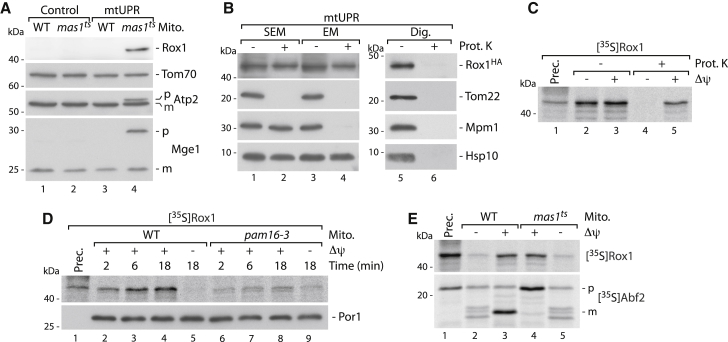

Rox1 Translocates to Mitochondria upon mtUPR

To test if the early mtUPR requires mtDNA, we analyzed mas1ts in the presence (rho+) or absence (rho0) of mtDNA. We found that cell growth and survival cannot be rescued upon mtUPR in the absence of mtDNA (Figures 3F and 3G). Gene expression of the reported nuclear Rox1 targets (COX5B, CYC7) was not affected upon mtUPR (Figure S2B). Together, this led us to hypothesize that the protective function of Rox1 upon mtUPR might depend on Rox1 localization to mitochondria. Live cell imaging demonstrated Rox1 co-localization with mitochondria in mas1ts upon mtUPR (Figure S5A). Western blotting of isolated mitochondria using specific Rox1 antibodies or HA-tagged Rox1 confirmed that Rox1 specifically localizes to mitochondria upon mtUPR in vivo (Figures 4A, 4B, and S5B). Sublocalization using protease protection assays after selective opening of the two mitochondrial membranes revealed the presence of Rox1 in the matrix (Figure 4B). We also tested if Rox1 can be imported as precursor protein in organello and incubated isolated mitochondria with radiolabeled Rox1 protein in the presence or absence of Δψ. Only in the presence of intact Δψ was Rox1 imported into a protease-protected location, demonstrating a characteristic inner mitochondrial protein location (Figure 4C; Burkhart et al., 2015, Vögtle et al., 2009). In contrast, transcription factors with reported overlapping nuclear function of Rox1 did not import (Figure S5C). Moreover, we found that Rox1 import depends on the PAM (import into pam16-3 mitochondria) (Chacinska et al., 2009, Endo and Yamano, 2009, Schulz et al., 2015), which directs precursor proteins from the import channel of the inner membrane into the matrix (Figure 4D), confirming our in vivo submitochondrial localization data (Figures 4A, 4B, S5A, and S5B) also in organello. An unusual feature of the Rox1 precursor is the lack of a cleavable N-terminal presequence, which is present in nearly all precursor proteins destined to the mitochondrial matrix (one of the rare exceptions is Hsp10, which is also imported via the presequence import pathway despite the lack of a cleavable presequence; Burkhart et al., 2015). In contrast, the only so far known mitochondrial HMG-box domain protein Abf2 harbors a 26 amino acid long presequence (Figure S5D) that is cleaved upon import by MPP (Figure 4E). Abf2 therefore requires MPP for maturation and functionality. Taken together, Rox1 does not require MPP processing for maturation and functionality and can bypass the presequence processing machinery upon its mtUPR-induced import into mitochondria. The dependence of the early mtUPR on the presence of mtDNA and the presence of an HMG-box domain in Rox1 tempted us to speculate that the protective role of Rox1 against intramitochondrial precursor aggregates might be directly linked to the mitochondrial genome.

Figure 4.

Rox1 Translocates to Mitochondria upon mtUPR

(A) Immunoblot analysis of wild-type (WT) and mas1ts mitochondria. m, mature; p, precursor.

(B) Immunoblot analysis of mitochondria incubated in the absence or presence of proteinase K in iso-osmotic (SEM) or hypo-osmotic (EM) buffer or after lysis with non-ionic detergent (Dig.). Hsp10, matrix marker; Mpm1, intermembrane space; Tom22, outer membrane.

(C) SDS-PAGE autoradiography of radiolabeled Rox1 precursor imported in isolated WT mitochondria for 30 min in the presence or absence of Δψ. Prec., precursor; Prot. K, proteinase K.

(D) Import reaction as in (C), into WT and pam16-3 mitochondria for indicated time. Samples were treated with Prot. K. Por1, loading control.

(E) Import of Rox1 and Abf2 precursor (as in C) into isolated WT and mas1ts mitochondria.

See also Figure S5.

Mitochondrial Rox1 Performs a TFAM-like Function upon mtUPR and Ensures Proteostasis and Cell Survival

Abf2/mtTFA belongs to the highly conserved TFAM (mitochondrial transcription factor A) family of mitochondrial proteins, which bind mtDNA via their HMG-box domains and control several steps in organellar DNA maintenance and transcription (Gensler et al., 2001, Larsson et al., 1996, West et al., 2015). As early mtUPR appears to depend on mtDNA (Figures 3F and 3G), we wondered if Rox1 might possess a TFAM-like function. Purified Rox1 protein could bind specifically to HMG-box binding protein consensus sites found in mtDNA when incubated with radiolabeled DNA probes (HMG9bp derived from the COX1 gene; HMG6bp contained the core HMG-box binding motif) (Figure 5A). To test for a role of Rox1 in mitochondrial genome maintenance, we performed in organello mtDNA replication assays. Isolated yeast mitochondria were pulse labeled with 33P-dCTP, followed by a chase to monitor the synthesis and stability of de novo synthetized mtDNA (Gensler et al., 2001). In order to assess the direct role of Rox1 in mtDNA maintenance, Rox1 precursor protein was imported in mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria prior to addition of radiolabeled nucleotides (Figures 5B and S5E; Gensler et al., 2001). Interestingly, we found that stability of de novo replicated DNA (chase) was enhanced by imported Rox1 compared with control reactions (import of mock lysate generated without addition of Rox1 mRNA) (Figure 5B). We next assessed mitochondrial transcription by de novo labeling with 33P-UTP. Import of Rox1 in mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria led to a significantly increased rate of mitochondrial transcription (Figure 5C). In vivo analysis of mitochondrial transcripts by qPCR upon mtUPR identified a strong decrease in mitochondrial gene expression upon loss of Rox1, while expression of nuclear genes was not affected (Figure 5D). In addition, in vivo translation of all mitochondrially encoded proteins (tested by incorporation of 35S-methionine; Richter-Dennerlein et al., 2015, Suhm et al., 2018) was severely compromised when Rox1 was lacking (Figure 5E) and targeting of Rox1 to mitochondria could compensate for a loss of the yeast TFAM homolog Abf2/mtTFA (Figures S5F–S5I). Thus, we conclude that Rox1 performs TFAM-like functions within mitochondria that ensure maintenance of mitochondrial transcription and translation upon mtUPR and is therefore crucial for balancing mitochondrial proteostasis and cellular survival (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial Rox1 Performs a TFAM-Like Function upon mtUPR

(A) Autoradiography of gel mobility shift assay using recombinant Rox1 protein and 33P-labeled HMG consensus sequences.

(B) De novo DNA synthesis (labeled by 33P-dCTP incorporation) in isolated mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria with and without prior import of Rox1 precursor protein. n = 3; data represent mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

(C) De novo transcription (labeled by 33P-UTP incorporation) in isolated mas1tsrox1Δ mitochondria with and without prior import of Rox1 precursor protein. n = 3; data represent mean ± SEM. Mitochondrial rRNAs were stained with methylene blue as loading control.

(D) Analysis of representative transcripts encoded by mitochondrial or nuclear DNA by qRT-PCR after cell growth at permissive (Ctrl.) or non-permissive (mtUPR) temperature. n = 6; data represent mean ± SEM (Table S2).

(E) Mitochondrial translation in mas1tsrox1Δ cells in the presence or absence of a Rox1-expressing plasmid. Labeled mtDNA-encoded proteins visualized by incorporation of 35S-methionine.

(F) Model of the early mtUPR pathway showing translocation of the stressTFAM Rox1 into mitochondria upon aggregation of accumulating precursor proteins in the matrix. Rox1 ensures maintenance and expression of mtDNA, thus protecting cells against the decline of transmembrane potential, respiratory activity, and cytosolic and mitochondrial translation and against accumulation of ROS.

Discussion

We find that the conditional mas1ts allele in yeast triggers the accumulation of precursor proteins within mitochondria that form insoluble aggregates and escape degradation. Inactivation of MPP activates a transcriptional stress response, including upregulation of cytosolic and mitochondrial chaperone networks only 2 h after induction of MPP impairment. Most mtUPR and related pathways discovered so far are triggered by induction of severe and often irreversible mitochondrial dysfunctions, such as deletion of mtDNA, chemical inhibition of respiratory chain activity, impairment of protein import pathways, or depletion of the mitochondrial chaperone network and have not enabled detection and dissection of early or mild dysfunctional processes and their mechanisms (Nargund et al., 2012, Vögtle and Meisinger, 2012, Taylor et al., 2014, Wrobel et al., 2015, Eisenberg-Bord and Schuldiner, 2017, Münch and Harper, 2016, Quirós et al., 2016, Hoogenraad, 2017, Shpilka and Haynes, 2018, Weidberg and Amon, 2018, Boos et al., 2019, Mårtensson et al., 2019). In comparison, the possibility of short and modest induction of mtUPR by MPP impairment offers a unique model that allows dissection of these very early steps in mtUPR pathways. In contrast to classical stress pathways, the early mtUPR pathway preserves cytosolic and mitochondrial translation activity and sustains the membrane potential and protein import capacity. This is mediated via retranslocation of the stressTFAM Rox1 to the mitochondrial matrix, where it bypasses the presequence processing machinery. Rox1 serves a TFAM-like function in promoting mtDNA maintenance and expression. Thus, a stressTFAM acts as first line of defense upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix and enables maintenance of membrane potential, import capacity, and notably also cytosolic translation. Early mtUPR contributes to balancing organellar proteostasis and promoting cell survival and may reflect one of the earliest events in mitochondrial stress response pathways. The high conservation of its initiators and effectors also opens up the exiting possibility that these early steps upon mtUPR may counteract human pathologies caused by dysfunctional mitochondrial proteostasis.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Atp2 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR863-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Atp3 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR1671-3 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Atp16 | Burkhart et al., 2015 | GR1967-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Abf2 | This study | GR2073-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Cox4 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR578-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Cox6 | Burkhart et al., 2015 | GR2015-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Isu1 | Wiedemann et al., 2006 | GR724-7 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Mdh1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR1088-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Mge1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 23210-5 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Rip1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR543-6 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tim21 | Burkhart et al., 2015 | GR3883-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tim44 | Burkhart et al., 2015 | GR1835-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp10 | Böttinger et al., 2015 | GR4925-3 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-AAC | Vögtle et al., 2017 | 227-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Msp1 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR1468-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Por1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR3622-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tom20 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR3225-7 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tom40 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 169-7 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Tom70 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | GR657-3 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Pgk1 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR754-1 |

| Anti-HA-Peroxidase, high affinity | Roche | RRID: AB_390917; Cat#12013819001 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Mpm1 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR3096-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Rox1 (affinity purified) | This study | GR5250-2 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Om45 | Burkhart et al., 2015 | GR1390-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Ssa1 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR1011-4 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Sss1 | Vögtle et al., 2017 | GR788-1 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Sod2preseq. (affinity purified) | Mossmann et al., 2014 | GR3409-4 |

| Penta-His antibody | QIAGEN | RRID: AB_2619735; Cat#34660 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) | Promega | Cat#L1195 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| L-[35S]-Methionine | Perkin Elmer | Cat#NEG009005MC |

| [α-33P]dCTP | Hartman Analytic | Cat#FF-205 |

| [α-33P]UTP | Hartman Analytic | Cat#FF-210 |

| 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine (DisC3) | Invitrogen | Cat#D306 |

| Dihydroethidium | Sigma | Cat#37291-25MG |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Rabbit reticulocyte lysate | Promega | Cat#L4540 |

| RTS Wheat Germ System | 5Prime | Cat#BR1401001 |

| Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#69504 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#74104 |

| NEBNext Ultra Directional Library Prep Kit | NEB | Cat#E7420 |

| NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Isolation Module | NEB | Cat#E7490 |

| ATP detection Kit | Abcam | Cat#ab113849 |

| NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris Protein Gels | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#WG1202BOX |

| High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Applied biosystems | Cat#4368814 |

| SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR® Green Supermix | BIORAD | Cat#1725271 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw RNA-seq data | This paper | Short Read Archive National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject PRJNA498270) |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| YPH499 (WT) MATa, ade2-101, his3-Δ200, leu2-Δ1, ura3-52, trp1 Δ63, lys2−801 | Sikorski and Hieter, 1989 | 1501 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1HA | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 4944 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144C-HA | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 4945 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 4947 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144C | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 4948 |

| YPH499-BG-mia1-3 (pam16-3) | Frazier et al., 2004 | 3158 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 aft1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH1WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Caft1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH1R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 aft2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH2WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Caft2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH2R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 cad1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH4WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Ccad1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH4R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 cup2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH5WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Ccup2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH5R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 gcr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH9WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cgcr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH9R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 hac1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH10WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Chac1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH10R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 hap4::natNT2 | This paper | DPH11WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Chap4::natNT2 | This paper | DPH11R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 hap5::natNT2 | This paper | DPH12WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Chap5::natNT2 | This paper | DPH12R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 hog1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH13WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Chog1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH13R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 hsp78::natNT2 | This paper | DPH14WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Chsp78::natNT2 | This paper | DPH14R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 ixr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH15WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cixr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH15R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 mdj1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH16WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cmdj1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH16R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 mig1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH17WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cmig1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH17R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 mot3::natNT2 | This paper | DPH18WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cmot3::natNT2 | This paper | DPH18R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 msn2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH19WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cmsn2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH19R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 msn4::natNT2 | This paper | DPH20WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cmsn4::natNT2 | This paper | DPH20R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 nrg1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH21WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cnrg1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH21R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 pdr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH22WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cpdr1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH22R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 pim1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH23WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cpim1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH23R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rgm1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH24WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crgm1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH24R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rox1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH25WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crox1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH25R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rox1::natNT2 pRS415-ROX1 | This paper | DPH28WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crox1::natNT2 pRS415-ROX1 | This paper | DPH28R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rox1::natNT2 pRS415 (empty vector) | This paper | DPH29WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crox1::natNT2 pRS415 (empty vector) | This paper | DPH29R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rox1::natNT2 pRS415-rox1HA | This paper | DPH30WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crox1::natNT2 pRS415- rox1HA | This paper | DPH30R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rtg1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH31WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crtg1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH31R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 skn7::natNT2 | This paper | DPH32WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cskn7::natNT2 | This paper | DPH32R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 sko1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH33WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Csko1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH33R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 stb3::natNT2 | This paper | DPH34WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cstb3::natNT2 | This paper | DPH34R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 ume6::natNT2 | This paper | DPH35WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cume6::natNT2 | This paper | DPH35R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 upc2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH36WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cupc2::natNT2 | This paper | DPH36R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 usv1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH37WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cusv1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH37R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 xbp1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH38WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cxbp1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH38R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 yap1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH39WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cyap1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH39R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 yap5::natNT2 | This paper | DPH40WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cyap5::natNT2 | This paper | DPH40R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 yap6::natNT2 | This paper | DPH41WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cyap6::natNT2 | This paper | DPH41R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 znf1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH42WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Cznf1::natNT2 | This paper | DPH42R144C |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rho0 | This paper | DPH43WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144C rho0 | This paper | DPH43R144C |

| YPH499 abf2::natNT2 pRS425 (empty vector) | This paper | DPH44 |

| YPH499 abf2::natNT2 pRS425-MTS1rox1 | This paper | DPH45 |

| YPH499 abf2::natNT2 pRS425-MTS2rox1 | This paper | DPH46 |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-MAS1 rox1::ROX1GFP-natNT2 om45::OM45mKate-URA3 | This paper | DPH47WT |

| YPH499 mas1::HIS3MX6 pFL39-mas1R144Crox1::ROX1GFP-natNT2 om45::OM45mKate-URA3 | This paper | DPH47R144C |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S2 | See Table S2 | See Table S2 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pFL39-MAS1 | Vögtle et al., 2018 | 2477 |

| pFL39-mas1R144C | Vögtle et al., 2018 | DPH-Pl1 |

| pFL39-mas1HA | Vögtle et al., 2018 | DPH-Pl2 |

| pFL39-mas1R144C-HA | Vögtle et al., 2018 | DPH-Pl3 |

| pFL39 | Bonneaud et al., 1991 | X15 |

| pRS415 | Christianson et al., 1992 | X24 |

| pRS415-ROX1 | This paper | DPH-Pl4 |

| pRS415-rox1HA | This paper | DPH-Pl5 |

| pRS425 | Christianson et al., 1992 | X30 |

| pRS425-MTS1rox1 | This paper | DPH-Pl6 |

| pRS425-MTS2rox1 | This paper | DPH-Pl7 |

| pFA6a-GFP-natNT2 | Janke et al., 2004 | DPH-Pl8 |

| pFA6a-link-yomKate2-CaURA3 | Lee et al., 2013 | DPH-Pl9 |

| pFA6a-HIS3MX6 | Longtine et al., 1998 | 1424 |

| pET10N-ROX1 | This paper | DPH-Pl10 |

| pGEM4Z-AAC | Meisinger lab | A01 |

| pFA6a-natNT2 | Janke et al., 2004 | 2721 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Institutes of Health, USA | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| oPOSSUM | Kwon et al., 2012 | http://opossum.cisreg.ca |

| ITEM software | Olympus | https://www.olympus-sis.com |

| Trim Galore 0.28 | N/A | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/ |

| TopHat v2.0.9 | Kim et al., 2013 | http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml |

| Samtools rmdup 2.0 | Li et al., 2009 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ |

| HTseq count 0.6 | Anders et al., 2015 | https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/release_0.11.1/count.html |

| Deseq2 2.1.8 | Love et al., 2014 | http://bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/vignettes/DESeq2/inst/doc/DESeq2.html |

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Chris Meisinger (chris.meisinger@biochemie.uni-freiburg.de). All unique reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental Models and Subject Details

Yeast strains used in this study are derivatives of the YPH499 S. cerevisiae strain. All strains are listed with their genotypes in the Key Resources Table. Yeast cells were grown in YPG medium (1% [w/v] yeast extract, 2% [w/v] bacto peptone, 3% [w/v] glycerol, pH 4.9), YPD medium (1% [w/v] yeast extract, 2% [w/v] bacto peptone, 2% [w/v] glucose, pH 4.9) or SM-Leu (selective minimal medium, 0.67% [w/v] yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.2% [w/v] SC amino acid mixture, 2% [w/v] glucose or 3% [w/v] glycerol and 0.1% [w/v] glucose) at 23°C (permissive conditions), 33°C, 35°C (mild mtUPR) or 37°C (mtUPR). The optical density (OD) of the cell culture was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600).

Method Details

Yeast strains and growth conditions

All Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are derived from YPH499 (Mata, ade2-101, his3-Δ200, leu2-Δ1, ura3-52, trp1-Δ63, lys2−801). The temperature-sensitive mutant strains mas1ts (R144C) and pam16-3 have been described in (Frazier et al., 2004, Vögtle et al., 2018). Deletion strains were generated by homologous recombination using a nourseothricin cassette (natNT2) (Janke et al., 2004). ROX1 was expressed under its endogenous promoter and terminator region using the plasmid pRS415. For targeting of Rox1 to mitochondria ROX1 was cloned into the pRS425 expression vector under its endogenous promoter and terminator. The mitochondrial targeting signals (MTS) from Aco1 (amino acids 1-15) and Cym1 (amino acids 1-10) were added to the Rox1 N terminus by PCR. The plasmids and the empty vector as control were transformed into a wild-type strain and the ABF2 gene was subsequently deleted by homologous recombination. Yeast strains lacking mitochondrial DNA were generated by ethidium bromide treatment. Yeast cells were inoculated in selective minimal medium with glucose for three days. Cells were plated on YPD plates and the presence of mtDNA-encoded genes was determined by PCR. For live-cell imaging the ROX1 gene was chromosomally tagged with a C-terminal GFP-tag and the OM45 gene with a C-terminal mKate tag.

For growth tests tenfold serial dilutions were spotted on agar plates containing YPD or YPG medium. Plates were incubated at different temperatures.

Determination of viability

Cells were inoculated to OD600 0.1 and grown for 12 h at permissive temperature (25°C) on media containing glycerol as carbon source. Cells were shifted to 35°C or 37°C for indicated time and then analyzed for viability using two different approaches. For determination of membrane integrity loss, cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI). To this end, 2⋅106 cells were harvested and washed once in 250 μL ddH2O. After resuspending in 250 μL PBS (25 mM potassium phosphate, 0.9% [w/v] NaCl, pH 7.2) containing 500 μg/l PI, cells were incubated for 10 min in the dark and washed once in 250 μL PBS. Subsequently, 30000 cells were evaluated via flow cytometry (BD LSR Fortessa and BD FACSDivia software). To quantify clonogenic survival, the cell number was determined using a CASY cell counting device (Schärfe Systems) and 300 cells were plated on YPglycerol agar plates. Plates were incubated at 25°C (permissive temperature) for 3 days and colony forming units (cfu) were quantified (Aufschnaiter et al., 2018). For survival plating of rho0 cells, cells were cultured and plated on media containing glucose as carbon source.

Isolation of mitochondria

Yeast cells were grown in YPG medium at 23°C, 35°C or 37°C. Cells were harvested in logarithmic growth phase (OD600 0.7-1.5), collected and mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation (Meisinger et al., 2006). Isolated mitochondria were resuspended in SEM buffer (250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2), aliquoted and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Aliquots were stored at −80°C. Crude mitochondria were subjected to sucrose gradient and ultracentrifugation at 125000 g for 1h at 4°C to obtain highly pure organelles (Meisinger et al., 2006).

Protein aggregation assay

Isolated mitochondria were lysed in 1% digitonin solubilization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 10% [v/v] glycerol) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C in an end-over-end shaker. Samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 16000 g. The pellet was resuspended in solubilization buffer. Proteins of supernatant and pellet fractions were precipitated with TCA. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

In organello protein import

Radiolabeled precursor proteins were generated in vitro using the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) in the presence of 35S-methionine. Rox1 chemical amounts were synthesized using the RTS wheat germ system (5 PRIME). Isolated mitochondria (20-60 μg) were resuspended in import buffer (3% [w/v] bovine serum albumin (BSA), 250 mM sucrose, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM L-methionine, 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2, 2 mM NADH, 2 mM ATP). Where indicated mitochondria were subjected to an in organello heat shock (15 min 37°C) prior to the import reaction. Import reactions were started by addition of radiolabeled or chemical amounts of precursors and incubated for different time points at 25°C or 30°C. Where indicated the membrane potential was dissipated prior to the import reaction by addition of AVO (8 μM antimycin A, 1 μM valinomycin and 20 μM oligomycin). Import reactions were terminated by addition of AVO and placing the samples on ice. Non-imported precursor proteins were digested by Proteinase K treatment (50-100 μg/ml) for 10 min on ice. Mitochondria were washed with SEM buffer. Samples were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The following molecular weight markers were used: Protein ladder NEB P7703 and P7704, Thermo Scientific 26616 and Sigma Low Molecular Weight LMW.

To assess mitochondrial degradation capacity pulse-chase import assays were performed. Radiolabelled Hsp10 was imported for 20 min at 37°C into isolated mitochondria (pulse), import was dissipated by addition of AVO and samples treated with Proteinase K. Samples were washed in SEM buffer followed by further incubation (chase) at 37°C in SEM. Samples were taken at different time points and mitochondria re-isolated by centrifugation at 16000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To study protein import and assembly samples were lysed in solubilization buffer and separated on a blue native gradient gel (BN-PAGE) followed by digital autoradiography.

Submitochondrial protein localization

Isolated mitochondria were resuspended in SEM or EM (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2) buffer. Where indicated samples were treated with Proteinase K (50 μg/ml) for 20 min on ice. Samples were precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunodecoration.

In organello protein degradation assay

Isolated mitochondria were resuspended in SEM buffer and incubated at 37°C (Vögtle et al., 2009). Samples were taken at various time points. Mitochondria were re-isolated by centrifugation at 16000 g for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in Laemmli buffer. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Expression and purification of recombinant Rox1

The ROX1 gene was cloned into the pET10N vector. Protein expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain and purification was performed as described before (Schmidt et al., 2011). Antiserum against Rox1 was generated in rabbits by immunization with the purified protein.

Gel mobility shift assay

Double-stranded 50-mer oligonucleotide DNA probes (50 fmol) containing HMG domains (9 bp (aaaattaaataaacatggctattgttctcatggtattttaggaaaaccca) and the core 6 bp (tgattgtcaatttagttaatcattgttattaataaaggaaagatataaaa) motifs, respectively) were labeled with Klenow fill-in kit and [α-33P]dCTP. As control, double-stranded 50-mer oligonucleotide DNA probe without HMG domain (Ctrl.; tagagtagcgaaacggattcgatacccgtgtagttctagtagtaaactat) was used. Reactions were carried out in 200 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 0.1 μg/μl BSA with 3.5 pmol Rox1 protein at 25°C for 20 min. Samples were resolved on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer (1M Tris, 1M boric acid, 200 mM EDTA). The gel was dried and analyzed by autoradiography. For competition experiments, the mtDNA sequence without HMG domain (Ctrl.) was used as heterologous competitor.

De novo DNA synthesis

Freshly isolated mitochondria (800 μg) were resuspended in incubation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM K2HPO4, 0.05 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ADP, 10 mM glutamate, 2.5 mM malate, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing 1 mg/ml BSA, 50 μM dTTP, 50 μM dATP, 50 μM dGTP and 20 μCi [α-33P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 h on a rotating wheel. For pulse-chase experiments, mitochondria were incubated with [α-33P]dCTP (final concentration 5 μM) for 2 h, followed by a chase (1 h) with non-radiolabeled dCTP (5 mM). Mitochondria were pelleted at 9000 g for 4 min at 4°C and washed twice with incubation buffer. Mitochondria were resuspended in 300 μL lysis buffer and DNA was isolated with the Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After DNA precipitation and centrifugation, nucleic acids were dissolved in DNA hydration solution at 55°C for 1 h. DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. After the gel run, wet transfer was performed in 20x SSC (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate dihydrate) overnight onto a nylon membrane (Amersham Hybond™-N+) (Gensler et al., 2001, Matic et al., 2018).

De novo RNA synthesis

400 μg isolated mitochondria were resuspended in incubation buffer (1 mg/ml BSA, 20 μCi [α-33P] UTP (3000 Ci/mmol)). Subsequently, the samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C on a rotating wheel. Mitochondria were re-isolated by centrifugation for 2 min at 9000 g, resuspended in 500 μL incubation buffer supplemented with 2 mM UTP and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Samples were centrifuged at 9000 g for 4 min at 4°C and mitochondria washed twice with incubation buffer. Mitochondrial RNA was purified by the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Samples were mixed in a 1:2 ratio with RNA sample loading buffer (Sigma), incubated at 65°C for 15 min, followed by 2 min incubation on ice. Samples were analyzed using Formaldehyde-agarose gels (1.2% agarose (RNase free, Ambion), 2.2 M formaldehyde in NorthernMax MOPS gel running buffer (Ambion)). Gels were vacuum dried and analyzed by autoradiography. For staining of mitochondrial rRNAs, a wet transfer was performed in 20x SSC overnight onto a nylon membrane followed by staining with Methylene Blue (Molecular Research Center Inc.) for 10 min.

RNA sequencing

Three biological replicates of wild-type and mas1ts yeast strains were grown at 24°C (permissive conditions) or for 2 h and 4 h at 37°C (non-permissive) in YPG medium. Cells were collected in logarithmic growth phase (OD600 0.7-1.5). RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The NEBNext Ultra Directional Library Prep Kit was used in combination with the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Isolation Module (NEB) to prepare strand-specific RNA libraries for Illumina sequencing from more than 100 ng RNA according to the manufacturer`s protocol. Libraries were sequenced on Illumina sequencers in paired-end mode (75 PE).

RNA-seq data analysis

Quality control and adaptor trimming was performed prior to mapping of sequencing reads to remove low quality reads and adaptor contaminations. Sequencing reads were mapped to the yeast genome (sacCer3) using Tophat2 (Kim et al., 2013). RNA fragments mapping to coding regions were counted using HTSeq count (Anders et al., 2015) and differential gene expression was assessed using Deseq2 (Love et al., 2014). Differentially expressed genes correspond to those displaying a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted FDR-corrected P-value ≤ 0.05 and a change of at least 1.3-fold.

In vivo cytosolic protein translation

Yeast cultures were grown in YPG or SM-Leu (with 3% glycerol) at 23°C or 37°C until logarithmic growth phase (OD600 0.5-1). Cells were harvested and washed twice in SM (3% glycerol) without methionine. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in SM without methionine and [35S]methionine was added. Cells were incubated at 23°C or 37°C and samples were taken at different time points. Cytosolic translation was terminated by addition of stop solution (150 μg/ml cycloheximide, 10 mM methionine). Samples were placed on ice and precipitated with TCA. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

In vivo mitochondrial protein translation

Yeast cells were inoculated in YPG or SM-Leu and grown at 23°C or 37°C. Cells were harvested in logarithmic growth phase (OD600 0.5-1) and washed twice in SM without amino acids. Cells were supplemented with an amino acid mix (2 mg/ml amino acids solution, minus methionine) and incubated at the respective growth temperature for 10 min. Cycloheximide (150 μg/ml) was added to the samples and incubated for additional 2.5 min. Cells were supplemented with [35S]methionine and incubated for different time points. Reactions were stopped by addition of cold methionine (10 mM) and stop solution (0.1 M NaOH, 1.1% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol, 3.3 mM PMSF, 13.3 μM puromycin). Cells were placed on ice for 10 min. TCA precipitation was performed and samples were analyzed via NuPAGE electrophoresis system (precast 10% Bis-Tris gels) and autoradiography.

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurement

The mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) was measured by fluorescence quenching using 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine (DisC3) (Mossmann et al., 2014). Isolated mitochondria were resuspended in membrane potential buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 0.1% [w/v] BSA, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 20 mM KPi, pH 7.2) supplemented with DisC3. Addition of valinomycin dissipated the membrane potential.

Measurement of mitochondrial ATP levels

Mitochondrial ATP levels were determined using isolated mitochondria suspended in 0.5 mL BES buffer (75% [v/v] EtOH, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4) (Aufschnaiter et al., 2018). Samples were incubated at 90°C for 3 min followed by centrifugation for 20 min at 4°C at 16000 g. The supernatant was diluted 20 times in 20 mM Tris (pH 8). 150 μL of the diluted sample were transferred to a 96-well plate and incubated for 5 min at RT. 50 μL substrate solution (ATP detection kit, Abcam) were added to the samples and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Luminescence was measured for 10 s using a plate reader (BMG LABTECH Reader CLARIOstar). Substrate solution without mitochondria was used as blank.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species were detected using the superoxide-driven conversion of non-fluorescent dihydroethidium (DHE) to fluorescent ethidium. Isolated mitochondria (20 μg) were resuspended in reaction buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KH2PO4) supplemented with 0.1 mM DHE and incubated for 10 min in the dark. Signal intensity was measured with a fluorescence reader (BMG LABTECH Reader CLARIOstar) using an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and emission wavelength of 604 nm. Blanks were taken from samples without mitochondria and the experiments were performed with biological and technical triplicates (Rhein et al., 2009).

Electron microscopy

Yeast cells were grown in YPG to an OD600 of 0.5-1 at 24°C or shifted for 10 h to 37°C. Cells were harvested and washed in PBS (8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Cells were resuspended in glutaraldehyde fixation buffer with 2% [v/v] glutaraldehyde (EM grade, high purity, Serva) in CaCo buffer (0.1 M sodium cacodylate, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2). Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C and washed three times with CaCo buffer. Subsequently cells were incubated with zymolyase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1.4 M sorbitol, 3 mg/ml zymolyase, 2% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol) for 15 min at 24°C or 37°C. Cells were re-isolated by centrifugation and washed two times with CaCo buffer. Yeast spheroblasts were then fixed in 4% [v/v] paraformaldehyde and 1% [v/v] glutaraldeyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). For electron microscopy samples were contrasted using 1% [w/v] osmium tetroxide (incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature in 0.1 M phosphate buffer) and 1% [w/v] uranyl actetate (45 minutes in 70% ethanol). The samples were then dehydrated and embedded in epoxy resin (Durcupan, Sigma) (Unger et al., 2017). Ultrathin sections were visualized using a Philips CM 100 TEM. Images of yeast cells were taken using ITEM software (Olympus).

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescent microscopy images were recorded with a DeltaVision Ultra High Resolution Microscope with UPlanSApo 100x/1.4 oil Olympus objective, using a sCMOS pro.edge camera at room temperature. For live cell imaging, 40 μL cells (OD600 0.5-1.0) were attached to 35 mm glass bottom dishes (1.5 mm glass (0.16-0.19 mm)) using Concavalin A. To follow the subcellular localization of Rox1-GFP and OM45-mKate upon temperature shift, Z stacks with optical section spacing of 0.25 μm for 5 μm sample thickness (21 optical sections per image per sample) were taken. Raw fluorescent microscopy images were deconvolved at the DeltaVision microscope using SoftWorx deconvolution plugin. All deconvolved images were analyzed with ImageJ/Fiji software. The quantification of the images was performed blindly using a randomizing macro.

RTqPCR analysis

Polyadenylated RNA was extracted from total RNA using oligod(T) paramagnetic beads and reverse transcribed (NEBNext reagents). The SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used for quantitative PCR. Reactions (quadruplicates, 5 μl) were analyzed using an CFX384 Real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Data were analyzed as previously described (Gilsbach et al., 2006) and TAF10 was selected as reference gene. Primers are listed in Table S2.

Measurement of mtDNA levels by qPCR

Total DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Mitochondrial DNA levels were quantified using primers for the COX1 gene. The gene ACT1 was used as control for normalizing mtDNA levels. Primers are listed in Table S2.

Miscellaneous

Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols. Primary antibodies used in this study are listed in the Key Resources Table. For western blotting primary antisera were diluted in 1 × TBS with 5% [w/v] milk powder. Affinity-purified antisera were diluted 1:50 in 1 × TBS with 0.01% [v/v] Tween. Antibodies against Abf2 were generated by immunization of rabbits using a synthetic peptide (KYIQEYKKAIQEYNARYP). The peptide was coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via N-terminal cysteines. To show regions of interest western blots and autoradiography scans were digitally processed.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Candidates of transcriptional factors involved in mtUPR (Table S1) were identified with the oPOSSUM (http://opossum.cisreg.ca/cgi-bin/oPOSSUM3/opossum_yeast_ssa) software. The software conditions selected were 14 bits, 85% of sequence threshold and 500 bp upstream sequence of the promoter (Kwon et al., 2012).

All experiments were replicated at least three times. Data shown represent means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical details of each experiment can be found in the figure legends. To analyze the effect of dependent variables with time and genotype as independent factors, a two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc was applied. A Student’s t test was applied to compare between two groups. Significances are indicated with asterisks: ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, not significant (n.s.) p > 0.05.

Data and Code Availability

All sequencing datasets reported in this manuscript are deposited in the Short Read Archive at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the BioProject PRJNA498270.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Schuldiner, N. Pfanner, N. Wiedemann, M. Ott, and M. Deckers for discussion and B. Schönfisch for technical assistance. We thank the EM facility (Department of Neuroanatomy Freiburg), B. Joch, and Dr. A. Vlachos for help with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging. Work included in this study was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral theses of D.P.H., M.L. and C. Kücükköse at the University of Freiburg. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), under Germany’s Excellence Strategy (CIBSS - EXC-2189 - Project ID 390939984), RTG 2202 and ME 1921/5-1 (to C.M.), SFB1381 (Project ID 403222702; to C.M., F.-N.V., and C. Kraft), CRC992 (to L. Hein), the Emmy-Noether Programm of the DFG (to F.-N.V.), DST-SERB, India (to A.M.), the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the Austrian Science Fund FWF/P27183-B24 (to S.B.), P25522-B20, and P28113-B28, the Vienna Science and Technology Fund WWTF/VRG10-001, from the EMBO Young Investigator Program, from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement 769065 (to C. Kraft), and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement 765912 (to M.L. and C. Kraft). This work reflects only the authors’ view and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Author Contributions

D.P.-H., S.M., A.M., L. Habernig, M.L., L.M., R.G., S.T.-C., D.P., P.M., O.K., C. Kücükköse, A.A.T., and F.-N.V. performed the experiments. D.P.-H., S.M., R.G., O.K., L. Hein, C. Kraft, S.B., F.-N.V., and C.M. designed experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. D.P.-H., F.-N.V., and C.M. developed the project and wrote the manuscript. F.-N.V. and C.M. coordinated and directed the project. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: October 17, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.026.

Contributor Information

Chris Meisinger, Email: chris.meisinger@biochemie.uni-freiburg.de.

F.-Nora Vögtle, Email: nora.voegtle@biochemie.uni-freiburg.de.

Supplemental Information

References

- Anders S., Pyl P.T., Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufschnaiter A., Kohler V., Walter C., Tosal-Castano S., Habernig L., Wolinski H., Keller W., Vögtle F.N., Büttner S. The enzymatic core of the Parkinson’s Disease-associated protein LRKK2 impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in aging yeast. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:205. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balchin D., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F.U. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science. 2016;353:aac4354. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneaud N., Ozier-Kalogeropoulos O., Li G.Y., Labouesse M., Minvielle-Sebastia L., Lacroute F. A family of low and high copy replicative, integrative and single-stranded S. cerevisiae/E. coli shuttle vectors. Yeast. 1991;7:609–615. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos F., Krämer L., Groh C., Jung F., Haberkant P., Stein F., Wollweber F., Gackstatter A., Zöller E., van der Laan M. Mitochondrial protein-induced stress triggers a global adaptive transcriptional programme. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:442–451. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttinger L., Oeljeklaus S., Guiard B., Rospert S., Warscheid B., Becker T. Mitochondrial heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 and Hsp10 cooperate in the formation of Hsp60 complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:11611–11622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart J.M., Taskin A.A., Zahedi R.P., Vögtle F.N. Quantitative profiling of substrates of the mitochondrial presequence processing protease reveals a set of nonsubstrate proteins increased upon proteotoxic stress. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:4550–4563. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacinska A., Koehler C.M., Milenkovic D., Lithgow T., Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138:628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson T.W., Sikorski R.S., Dante M., Shero J.H., Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg-Bord M., Schuldiner M. Ground control to major TOM: mitochondria-nucleus communication. FEBS J. 2017;284:196–210. doi: 10.1111/febs.13778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Yamano K. Multiple pathways for mitochondrial protein traffic. Biol. Chem. 2009;390:723–730. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier A.E., Dudek J., Guiard B., Voos W., Li Y., Lind M., Meisinger C., Geissler A., Sickmann A., Meyer H.E. Pam16 has an essential role in the mitochondrial protein import motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:226–233. doi: 10.1038/nsmb735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensler S., Weber K., Schmitt W.E., Pérez-Martos A., Enriquez J.A., Montoya J., Wiesner R.J. Mechanism of mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication: import of mitochondrial transcription factor A into isolated mitochondria stimulates 7S DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3657–3663. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsbach R., Kouta M., Bönisch H., Brüss M. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo reference genes for internal standardization of real-time PCR data. Biotechniques. 2006;40:173–177. doi: 10.2144/000112052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbauer A.B., Zahedi R.P., Sickmann A., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. The protein import machinery of mitochondria—a regulatory hub in metabolism, stress, and disease. Cell Metab. 2014;19:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad N. A brief history of the discovery of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response in mammalian cells. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2017;49:293–295. doi: 10.1007/s10863-017-9703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C., Magiera M.M., Rathfelder N., Taxis C., Reber S., Maekawa H., Moreno-Borchart A., Doenges G., Schwob E., Schiebel E., Knop M. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21:947–962. doi: 10.1002/yea.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S.L. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon A.T., Arenillas D.J., Worsley Hunt R., Wasserman W.W. oPOSSUM-3: advanced analysis of regulatory motif over-representation across genes or ChIP-Seq datasets. G3 (Bethesda) 2012;2:987–1002. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.003202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson N.G., Garman J.D., Oldfors A., Barsh G.S., Clayton D.A. A single mouse gene encodes the mitochondrial transcription factor A and a testis-specific nuclear HMG-box protein. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:296–302. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Lim W.A., Thorn K.S. Improved blue, green, and red fluorescent protein tagging vectors for S. cerevisiae. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Barrientos A. Transcriptional regulation of yeast oxidative phosphorylation hypoxic genes by oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19:1916–1927. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M.S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D.J., Shah N.G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J.R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani J., Meisinger C., Schneider A. Peeping at TOMs—diverse entry gates to mitochondria provide insights into the evolution of eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:337–351. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson C.U., Priesnitz C., Song J., Ellenrieder L., Doan K.N., Boos F., Floerchinger A., Zufall N., Oeljeklaus S., Warscheid B., Becker T. Mitochondrial protein translocation-associated degradation. Nature. 2019;569:679–683. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic S., Jiang M., Nicholls T.J., Uhler J.P., Dirksen-Schwanenland C., Polosa P.L., Simard M.L., Li X., Atanassov I., Rackham O. Mice lacking the mitochondrial exonuclease MGME1 accumulate mtDNA deletions without developing progeria. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1202. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisinger C., Pfanner N., Truscott K.N. Isolation of yeast mitochondria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;313:33–39. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossmann D., Vögtle F.N., Taskin A.A., Teixeira P.F., Ring J., Burkhart J.M., Burger N., Pinho C.M., Tadic J., Loreth D. Amyloid-β peptide induces mitochondrial dysfunction by inhibition of preprotein maturation. Cell Metab. 2014;20:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A., Yang C.S., Wei B., Weiner H. Precursor protein is readily degraded in mitochondrial matrix space if the leader is not processed by mitochondrial processing peptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37266–37275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch C., Harper J.W. Mitochondrial unfolded protein response controls matrix pre-RNA processing and translation. Nature. 2016;534:710–713. doi: 10.1038/nature18302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund A.M., Pellegrino M.W., Fiorese C.J., Baker B.M., Haynes C.M. Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science. 2012;337:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1223560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert W., Herrmann J.M. Translocation of proteins into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.163409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari J., Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirós P.M., Langer T., López-Otín C. New roles for mitochondrial proteases in health, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:345–359. doi: 10.1038/nrm3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirós P.M., Mottis A., Auwerx J. Mitonuclear communication in homeostasis and stress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:213–226. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhein V., Song X., Wiesner A., Ittner L.M., Baysang G., Meier F., Ozmen L., Bluethmann H., Dröse S., Brandt U. Amyloid-beta and tau synergistically impair the oxidative phosphorylation system in triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:20057–20062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905529106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Dennerlein R., Dennerlein S., Rehling P. Integrating mitochondrial translation into the cellular context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:586–592. doi: 10.1038/nrm4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M.T., Hoogenraad N.J. Mitochondrial-nuclear communications. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:701–722. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.091720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O., Harbauer A.B., Rao S., Eyrich B., Zahedi R.P., Stojanovski D., Schönfisch B., Guiard B., Sickmann A., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. Regulation of mitochondrial protein import by cytosolic kinases. Cell. 2011;144:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C., Schendzielorz A., Rehling P. Unlocking the presequence import pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpilka T., Haynes C.M. The mitochondrial UPR: mechanisms, physiological functions and implications in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:109–120. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R.S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhm T., Kaimal J.M., Dawitz H., Peselj C., Masser A.E., Hanzén S., Ambrožič M., Smialowska A., Björck M.L., Brzezinski P. Mitochondrial translation efficiency controls cytoplasmic protein homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1309–1322.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R.C., Berendzen K.M., Dillin A. Systemic stress signalling: understanding the cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:211–217. doi: 10.1038/nrm3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira P.F., Glaser E. Processing peptidases in mitochondria and chloroplasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topf U., Suppanz I., Samluk L., Wrobel L., Böser A., Sakowska P., Knapp B., Pietrzyk M.K., Chacinska A., Warscheid B. Quantitative proteomics identifies redox switches for global translation modulation by mitochondrially produced reactive oxygen species. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:324. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02694-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger A.K., Geimer S., Harner M., Neupert W., Westermann B. Analysis of yeast mitochondria by electron microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1567:293–314. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6824-4_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vögtle F.N., Meisinger C. Sensing mitochondrial homeostasis: the protein import machinery takes control. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vögtle F.N., Wortelkamp S., Zahedi R.P., Becker D., Leidhold C., Gevaert K., Kellermann J., Voos W., Sickmann A., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. Global analysis of the mitochondrial N-proteome identifies a processing peptidase critical for protein stability. Cell. 2009;139:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vögtle F.N., Burkhart J.M., Gonczarowska-Jorge H., Kücükköse C., Taskin A.A., Kopczynski D., Ahrends R., Mossmann D., Sickmann A., Zahedi R.P., Meisinger C. Landscape of submitochondrial protein distribution. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:290. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00359-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vögtle F.N., Brändl B., Larson A., Pendziwiat M., Friederich M.W., White S.M., Basinger A., Kücükköse C., Muhle H., Jähn J.A. Mutations in PMPCB encoding the catalytic subunit of the mitochondrial presequence protease cause neurodegeneration in early childhood. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;102:557–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidberg H., Amon A. MitoCPR-A surveillance pathway that protects mitochondria in response to protein import stress. Science. 2018;360:6385. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A.P., Khoury-Hanold W., Staron M., Tal M.C., Pineda C.M., Lang S.M., Bestwick M., Duguay B.A., Raimundo N., MacDuff D.A. Mitochondrial DNA stress primes the antiviral innate immune response. Nature. 2015;520:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nature14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann N., Urzica E., Guiard B., Müller H., Lohaus C., Meyer H.E., Ryan M.T., Meisinger C., Mühlenhoff U., Lill R., Pfanner N. Essential role of Isd11 in mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster synthesis on Isu scaffold proteins. EMBO J. 2006;25:184–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel L., Topf U., Bragoszewski P., Wiese S., Sztolsztener M.E., Oeljeklaus S., Varabyova A., Lirski M., Chroscicki P., Mroczek S. Mistargeted mitochondrial proteins activate a proteostatic response in the cytosol. Nature. 2015;524:485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature14951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing datasets reported in this manuscript are deposited in the Short Read Archive at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the BioProject PRJNA498270.