Abstract

Background

Low and middle-income countries like India with a large youth population experience a different environment from that of high-income countries. The Consortium on Vulnerability to Externalizing Disorders and Addictions (cVEDA), based in India, aims to examine environmental influences on genomic variations, neurodevelopmental trajectories and vulnerability to psychopathology, with a focus on externalizing disorders.

Methods

cVEDA is a longitudinal cohort study, with planned missingness design for yearly follow-up. Participants have been recruited from multi-site tertiary care mental health settings, local communities, schools and colleges. 10,000 individuals between 6 and 23 years of age, of all genders, representing five geographically, ethnically, and socio-culturally distinct regions in India, and exposures to variations in early life adversity (psychosocial, nutritional, toxic exposures, slum-habitats, socio-political conflicts, urban/rural living, mental illness in the family) have been assessed using age-appropriate instruments to capture socio-demographic information, temperament, environmental exposures, parenting, psychiatric morbidity, and neuropsychological functioning. Blood/saliva and urine samples have been collected for genetic, epigenetic and toxicological (heavy metals, volatile organic compounds) studies. Structural (T1, T2, DTI) and functional (resting state fMRI) MRI brain scans have been performed on approximately 15% of the individuals. All data and biological samples are maintained in a databank and biobank, respectively.

Discussion

The cVEDA has established the largest neurodevelopmental database in India, comparable to global datasets, with detailed environmental characterization. This should permit identification of environmental and genetic vulnerabilities to psychopathology within a developmental framework. Neuroimaging and neuropsychological data from this study are already yielding insights on brain growth and maturation patterns.

Keywords: Externalizing disorders, Study protocol, Vulnerabilities, Longitudinal study, Cohort, Environmental exposures

Background

India is home to the world’s largest number of adolescents and young people (10–24 years old), comprising about a third (>400 million) of its population [1]. Nearly 20% of young people experience a mental health condition, bearing a disproportionately high burden of mental morbidity [2–4]. The Consortium on Vulnerability to Externalizing Disorders and Addictions (cVEDA) is a multi-site, international, collaborative, cohort study in India, setup to examine the interactions of environmental exposures, and genomic influences on neurodevelopmental trajectories and downstream vulnerability to psychopathology, with a specific focus on externalizing spectrum disorders. cVEDA spans seven recruitment centres, representing different geographical, physical and socio-cultural environments, across India. This paper presents the background, rationale and protocol of the cVEDA study.

The need for longitudinal studies using dimensional, multi-modal measures to study the etiopathological basis of psychiatric morbidity

Birth-cohort studies show that >70% psychiatric illnesses in adults begin before the age of 18 years [5]. Temperamental and psychological disturbances during childhood are prominent predictors of psychiatric disorders in adult life [6]. Childhood onset psychiatric disorders often extend into adulthood on a homotypic or heterotypic continuum [7]. Psychiatric morbidity is increasingly believed to be predicated upon a shared genetic and neurodevelopmental continuum, suggested by commonalities in clinical phenotype, neuroimaging characteristics, neuropsychological impairments, and environmental risk factors [8, 9]. Different psychiatric disorders rather than being discrete categories, possibly reflect differences in timing, severity and patterns of genetic expression and neurodevelopmental deviations [10]. Longitudinal studies over the developmental lifespan are ideally suited to study origins of psychiatric morbidity by tracking developmental trajectories, identifying deviations, and studying how deviations, and their interactions with genes and environment, relate to psychopathology [11–13]. Additionally, a combination of neuroimaging, neuropsychological, toxicological, and psychometric modalities better facilitates construction of models with high predictive power [14].

Role of the ‘exposome’ in determining psychiatric morbidity and the need to study it in low and middle-income countries

Psychiatric disorders have complex, multi-factorial, poly-gene-environmental etiologies [15]. Gene x environment correlation (rGE) and interaction (GxE) are two broad mechanisms that underlie this complex interface [16]. The exposome [17] includes general external environment (socio-economic, habitat), specific external environment (pollutants, infectious agents, substance use) and internal environment (physical activity, oxidative stress, etc.) [18]. Table 1 depicts the time-dependent impact of environmental exposures on developmental and psychopathological outcomes [19, 20].

Table 1.

Developmental and psychopathological impact of environmental exposures over different life stages

| Life stage | Exposure | Developmental impact | Impact on mental morbidity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetus | Maternal mal-nutrition | Early brain development, including key serotonergic and dopaminergic signalling systems | Externalizing problems in early childhood [21] |

| Intra-uterine growth retardation/Low birth weight | Developmental programming of physiological systems | Wide range of cognitive, emotional and behavioural outcomes [22] | |

| Maternal substance use | Later growth and development including trans-generational effects [23] | Wide range of cognitive, emotional and behavioural outcomes | |

| Psychosocial stress during pregnancy/ maternal depression & anxiety | Behavioural disturbances in later childhood [24] | ||

| Environmental pollutants – toluene in traffic smoke, organophosphates in pesticides | Developmental neurotoxicity; Neuroimaging evidence of structural abnormalities | Cognitive deficits [25, 26] | |

| Early childhood | Pollutants, environmental toxins – polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biomass fuels, tobacco smoke, arsenic in ground water, fluoride, lead, polychlorinated biphenyls from insulators in electrical equipment, phthalates from plastics and cosmetics | Injury to the developing human brain either through direct toxicity or interactions with the genome [27] | Low verbal IQ [29]; Cognitive deficits among preschool-age children [30]; behavioral abnormalities [31] |

| Neurotoxicity with effects persistent throughout life [28] | |||

| Absence of primary attachment figure/poor parenting | Deficits in cognitive and socio-emotional development [32] | Indiscriminate friendliness, poor peer relationships [33] | |

| Under-nutrition | Synaptic pruning, Myelination, Executive functioning [34, 35] | Risk of emotional and behavioural problems [36]; High prevalence of health-harming behaviours [37] | |

| Childhood & adolescence | Poverty/deprived neighbourhoods | Via parental psychopathology, less positive parenting, neglect, poor monitoring [38] | Higher prevalence of SUDs [39]; various negative behavioural outcomes [40]; Conduct problems [41] |

| Exposure to war and conflict | Range of psychopathology, including post-traumatic stress disorder [42] | ||

| High conflict home environment (parental marital conflict, parental divorce) | Disruptive behaviours [43] | ||

| Harsh parenting, physical abuse | Disruptive and emotional psychopathology [44] | ||

| Deviant peer relationships | Behavioural reinforcement, exchange of techniques | Delinquentbehaviours [45] | |

| Adolescence | Substance use | Interferes with brain maturation especially in areas affecting self-regulation and control | Substance use disorders and global difficulties in adult functioning [46] |

The exposome, which can potentially modify genetic expression, is multi-cultural. Extrapolating findings from high-income settings to low and middle-income countries (LMIC) is problematic [47]. Ethnic backgrounds, in a diverse country like India [48], and the prevalence of exposures and outcomes pertinent to development and health vary by income group and geography [49–51]. Certain environmental risk factors (nutritional stress, environmental neurotoxins and culturally dependent forms of psychosocial stress) are largely specific to developing societies. Maternal malnutrition, suboptimal breast-feeding, childhood malnutrition, unsafe water, poor sanitation, indoor smoke, and high-risk behaviors are leading causes of death and disability-adjusted life years in LMIC [52, 53]. It is necessary to study the exposome, in diverse settings, transactionally and longitudinally, with attention to both distal and proximal influences [54] to understand its role in psychopathology/resilience [55]. Setting up longitudinal studies in LMIC, using measures comparable to existing studies can provide a more nuanced understanding of the gene-environment contributions to psychiatric morbidity.

The focus on externalizing disorders

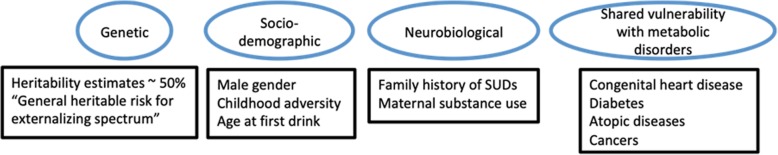

Externalizing disorders are the third most prevalent class of mental disorders (after anxiety and depression) [56]. These include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), Conduct disorder (CD) in childhood, and adult ADHD, mood disorders, substance use disorders, impulse control disorders, emotionally-unstable personality disorder, and antisocial personality disorder in adulthood. They are associated with significant impairment, and health and non-health sector costs [57, 58]. A dimensional framework of “externalizing psychopathology” encompasses poor impulse control, poor attention allocation, heightened emotional reactivity, verbal and physical aggression, violation of rules, and substance abuse [59]. Individuals at ‘high risk’ for externalizing disorders have different patterns of brain activity, neuroadaptation, cognition, and externalizing temperamental traits [60–66]. A number of studies have documented variations in brain regional volumes [67], regional white matter integrity [68], functional blood flow characteristics [69, 70], social intelligence and corresponding functional brain activations [71], brain activation patterns during response inhibition tasks [72], differences in neurophysiological parameters like P300 and pre-exposure cognitive deficits [62]. Interestingly, network disruptions are incrementally related to externalizing symptoms and are proportional to the alcoholism family density [73]. These variations are also seen as intermediate phenotypes in individuals with externalizing disorders [74–76], suggesting that maturation delays, deficits and deviations predate disorder onset and hold promise as early identification markers of vulnerability. Preliminary investigations have also shown that young adults at ‘high risk’ could ‘catch-up’ on brain maturational differences, emphasizing the role of early interventions [77, 78]. The externalizing spectrum has complex, multi-factorial underpinnings (Fig. 1), strong links with sequential development of various disorders and plausibly a common inherited causality [5]. This makes them particularly interesting in the search for common genetic and neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities and moderating environmental influences.

Fig. 1.

Complex, multi-factorial underpinnings of externalizing disorders [60–66, 79–81]

Key concepts emerging from research on the etiopathological basis of psychiatric morbidity have highlighted – a genetic and neurodevelopmental continuum, a poly-gene-environmental etiopathogenesis, unique socio-cultural contexts as environmental determinants of psychopathology, variations in brain trajectories leading to different psychopathological outcomes, and the differential impacts of environmental stressors on developmental trajectories over various life-stages. It follows that studying disparate environmental influences, across the developmental lifespan, on genetically determined trajectories of multimodal brain endophenotypes, using dimensional, multi-modal measures in a longitudinal framework could uncover key etiopathological processes underlying psychiatric morbidity.

The cVEDA collaboration

The c-VEDA is a collaborative venture between researchers from India and the United Kingdom (UK), set up under a joint initiative on the aetiology and life-course of substance misuse and its relationship with mental illness, by the Medical Research Council, UK (MRC) and the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR). National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore (NIMHANS) and King’s College London (KCL) are the coordinating centres in India and the UK, respectively. Other participating centres from India include – (i) Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh (PGIMER), (ii) ICMR-Regional Occupational Health Centre (ROHC), Kolkata, (iii) Regional Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal (RIMS), (iv) Holdsworth Memorial Hospital, Mysore (HMH), (v) Rishi Valley Rural Health Centre, Chittoor (RV), and vi) St. John’s Research Institute, Bangalore (SJRI). European collaborators include researchers who are part of major longitudinal imaging genetics studies – “Reinforcement-related behaviour in normal development and psychopathology” (IMAGEN) (https://imagen-europe.com), the “Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children” (ALSPAC) (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/), and the “Study of Cognition, Adolescents and Mobile Phones” (SCAMP) (https://www.scampstudy.org).

Objectives of the cVEDA study

The cVEDA study is designed to (a) establish a cohort of about 10,000 individuals within specified age bands – 6–11, 12–17, 18–23 years; (b) Conduct detailed phenotypic characterization, with special emphasis on externalizing behaviors (temperament and disorders), in the cohort and parents of all participants; (c) Assess environmental exposures (psychosocial stressors, societal discrimination, nutrition and asset security, environmental toxins) thought to impact gene expression, brain development, temperaments and behaviors; (d) Establish a sustained and accessible data platform and a bio-resource with an integrated database to facilitate analyses and collaborations; and (e) Build research capacity by joint UK–India initiatives.

Methods/Design

Study design

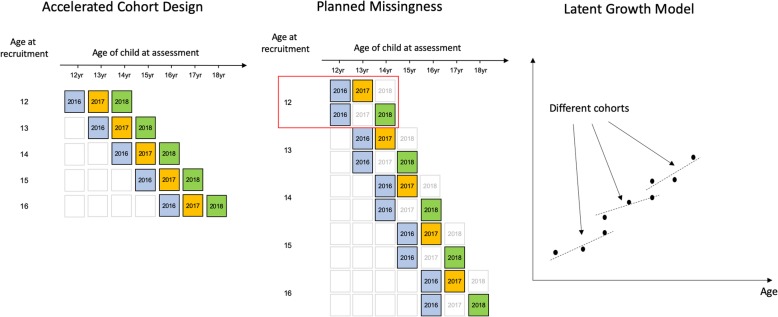

The cVEDA is a cohort of individuals aged 6–23 years across 7 Indian sites. It draws upon existing research systems with well-established tracking and follow-up mechanisms, previously employed in studying the impacts of varied risk factors on non-communicable diseases [82–85]. Cohorts recruited at each centre are followed-up 1 and 2 years after baseline assessments. The study employs a planned missingness [86] (Fig. 2) approach in which participants are randomised to follow-up either 1 or 2 years after enrolment. Such a design permits three waves of data collection to be achieved while reducing the cost of measurement per wave. Since participants are randomly assigned to be present/missing at each follow-up, missing data are completely at random and hence parameters of interest can be estimated without bias. In addition, loss-to-follow up can be reduced as participants suffer less with study-fatigue and also fieldworkers can target their limited resources more effectively when encouraging participants to return.

Fig. 2.

Accelerated longitudinal with planned missingness design and the generation of developmental trajectories (latent growth model)

Since the primary interest of the study is in tracking development over almost the entire developmental lifespan there are cost/time benefits due to recruiting across a wide range of participant ages. Age-variability within-wave permits an accelerated cohort design [87] to be employed (Fig. 2). Here a given age-range can be spanned in a shorter period of time by considering the cohort as being comprised of multiple sub-cohorts each of a different age at recruitment. A variety of longitudinal statistical models, either within a Structural Equation Modelling or Multilevel Modelling framework, including latent growth models (aka mixed-effects models) can take full advantage of such data. For example, using at joint model one might examine the longitudinal interplay between alcohol use and antisocial behaviour through adolescence. In addition, these models, through their use of a maximum-likelihood approach to missing data, based on a Missing At Random assumption, can demonstrate a high level of statistical power for a fraction of the monetary and time costs of following all individuals for the whole time period. Such an analytical framework is also compatible with the planned-missingness aspect to the study design described above.

Timeline

The cVEDA study started in February 2016. After 9 months spent in study set up (staff recruitment, translations of study instruments into 7 Indian regional languages, setting up digital data capture platform, training of recruitment and assessment teams, and quality control exercises), recruitment started in October 2016. Recruitment, baseline assessments and randomized follow-up have been continued in parallel. Under the current funding cycle, we have completed recruitment and baseline assessments; and 1 and 2 year follow-ups on a part of the sample (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

cVEDA study timeline

Sample

Baseline Clinical Assessment: The cVEDA had a target baseline sample size of approximately 10,000 participants in three age bands: C1 (6–11 years), C2 (12–17 years) and C3 (18–23 years). As the objectives of the study were to carry out detailed phenotypic characterisation of participants, examine their environmental exposures and gene-environment interactions that may modulate brain development and affect externalizing and addictive behaviour patterns, the study sample needed to be as large as feasibly possible whilst being representative of the geographic, socioeconomic and cultural diversity of India. The target sample sizes at each recruitment site were decided based upon each site’s estimated capacity to recruit individuals over a 3-year recruitment period, given the site lead’s understanding about ground realities and experience from past studies. The sample represents five geographically, ethnically, and socio-culturally distinct regions; varied environmental risks: toxic exposures (coal-mines), slum-dwellers, socio-political conflict zones (insurgency and inter-ethnic violence); urban and rural areas; school and college attendees; and familial high risk (children of parents with substance use or other mental disorders), in order to have an adequate representation of individuals likely to convert to externalizing disorders.

The study followed non-probabilistic convenience sampling based on accessibility to potential participants in local schools, colleges, community and clinics. Exclusion criteria included legal blindness/deafness, seizure disorder active in the last 1 month, severe physical or active mental illness, refusal of consent, or inability to participate in follow-up assessments (e.g. due to migration). Individuals with specific contra-indications (metal implants, electrical devices, severe claustrophobia) were excluded from neuroimaging. Site-wise exposure characteristics and baseline sample sizes are depicted in Fig. 4. Whilst the recruitment approach was pragmatic, this type of sampling technique may not allow for results that can be generalised to the entire population. However, given the scope and breadth of exposures being assessed, this approach is useful for the target research objectives and may help generate new hypotheses for future studies [88].

Fig. 4.

cVEDA sample distribution and recruitment site characteristics

(Map of India source: http://mapsopensource.com/india-states-outline-map-black-and-white.html; As stated on the webpage “All the content by www.mapsopensource.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License”)

Biological samples and neuroimaging: Blood/buccal swab and urine samples were collected from participants at baseline. Around 15% of the baseline sample, i.e. consenting participants, underwent neuroimaging. Even at the risk of biased sampling, this strategy was adopted given the wide age range, high rate of refusal, especially in non-clinical populations, and the unavailability of research MRI scanners in 4 out of 7 sites.

Procedure

a) Phenotypic characterization

Assessments involved dimensional and categorical phenotypic characterization. The questionnaires and assessment protocols were translated (and back-translated using standard WHO protocols) from English into seven Indian languages (Hindi, Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, Manipuri, Bengali, Punjabi) for use across seven recruitment sites. Age-appropriate instruments are used to capture socio-demographic information, temperament, environmental exposures, parenting, psychiatric morbidity, and neuropsychological functioning. Table 2 details the domains of assessments, tools and protocols.

Table 2.

cVEDA sample characterisation: Assessment domains, tools& protocols

| Assessment domain | Questionnaires | 6–11 years | 12–17 years | 18–23 years | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic information | Socio-demographic questionnaire [89] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Migration questionnaire [90] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Exposures questionnaires | Environmental exposures questionnaire [91] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Adverse childhoodexperiences – International questionnaire [37] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale [92] | |||||

| Short food questionnaire (modified Food Frequency Questionnaire) [93] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Pregnancy History Instrument – Revised [94] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Indian Family Violence and Control Scale [95] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mobile use questionnaire (Self-report) [96] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Mobile use questionnaire (Parent-report) –from the SCAMP study (https://www.scampstudy.org) | ✓ | ||||

| Life Events Questionnaire [97] | ✓ | ||||

| Questions on urbanicity (devised to explore all places a participant has successively resided at) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Parenting | Alabama parenting questionnaire – Child & Parent [98, 99] | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Adolescent attachment questionnaire [100] | ✓ | ||||

| Parental bonding instrument [101] | ✓ | ||||

| Temperament | Childhoodbehavior questionnaire [102] | ✓ | |||

| Early adolescent temperament questionnaire [103] | ✓ | ||||

| Adult temperament questionnaire [104] | ✓ | ||||

| Big Five Personality inventory [105] | ✓ | ||||

| Strengths & difficulties questionnaire – Parent [106] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Strengths & difficulties questionnaire – Child [107] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Strengths & difficulties questionnaire – Self-report [107] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Psychiatric morbidity | MINI-KID [108] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| MINI-5 [109] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ASSIST-Plus [110–113] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ASRS – ADHD [114] | ✓ | ||||

| Family history | Family history questionnaire (clinical assessment for presence of medical and/or psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives of the participant) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Medical history | Medical problems questionnaire (clinical assessment for presence of medical disorders in the participant) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Puberty | PubertalDevelopmentScale [115] | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Neuropsychological assessment | Psychology Experiment Building Language (PEBL)[96] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Digit span test – forward and reverse | |||||

| Corsi block test – forward and reverse | |||||

| Now or later test | |||||

| Trail making test | |||||

| Sort the cards | |||||

| Stop signal task [122] | |||||

| Balloon analogue risk task [121] | |||||

| Emotion recognition task | |||||

| Social Cognition Rating Tool in the Indian Setting [116] | |||||

| Anthropometry | Height | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weight | |||||

| Mid arm circumference | |||||

| Leg length | |||||

| Head circumference | |||||

| Neuroimaging | Structural MRI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| T1-weighted, 3D magnetization prepared gradient echo sequence (MPRAGE) based on the ADNI protocol (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/ADNI/Cores/index.shtml): | |||||

| T2 weighted fast- (turbo-) spin echo | |||||

| FLAIR scans | |||||

| Diffusion MRI | |||||

| Single-shot spin-echo EPI sequence | |||||

| Single acquisition session | |||||

| Acquisition repeated with reversed blips | |||||

|

Resting state functional MRI BOLD functional images acquired with a gradient- echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence, using a relatively short echo-time to optimize reliable imaging of subcortical areas. | |||||

| Toxicology | Urinary volatile organic compounds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Solid phase extraction followed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. | |||||

| Urinary Arsenic | |||||

| Flow injection system by Atomic | |||||

| Absorption Spectrometer (PerkinElmer AA800, USA) | |||||

| Plasma lead | |||||

| Transversely-heated graphite furnace and Zeeman background correctionusing Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (PerkinElmer AA800, USA) |

Neuroimaging

Resting state fMRI (rsfMRI), Diffusion MRI (dMRI) and Structural MRI (sMRI) scans are done at baseline, and are being done for the randomized consenting participants at follow-up. Structural and rsfMRI are collected on 3 T scanners (Siemens, Germany; Philips, The Netherlands). To ensure comparability of image-acquisition techniques and ‘pool’ability of the multi-site MRI data, a set of parameters, particularly those directly affecting image contrast or signal-to-noise are held constant across sites (https://cveda.org/standard-operating-procedures/) (Table 2).

Blood/saliva samples for genetic studies

Blood samples (at least 10 ml, EDTA and Tempus tubes) are collected at baseline for DNA, RNA and plasma lead estimation, as per a Standard Operating Protocol (https://cveda.org/standard-operating-procedures/). Plasma, ‘buffy coat’ (white blood cells) and red blood cells, from centrifugation of blood samples in EDTA tubes, are transferred into labeled aliquots for storage at a central biobank. Tempus tubes and blood component aliquots are stored at − 80 °C. Samples are kept frozen at all times including during transport using temperature-controlled logistics. For participants who do not consent for a blood sample, or where it isn’t possible to obtain a blood sample (e.g. failure to identify a suitable vein for blood draw or an insufficient amount of blood sample), a buccal swab (for DNA) is taken.

Plasma and urine samples for toxicological studies

Estimation of lead in plasma, and arsenic, metabolites of tobacco (cotinine) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), in urine samples, is incorporated in cVEDA as a measure of exposure to environmental neurotoxins. An aliquot of plasma isolated from blood samples is used for lead estimation. Lead is estimated in plasma as evidence suggest that plasma lead represents the toxicologically labile fraction of lead freely available to interact with target tissue rather than lead in whole blood [117, 118]. Mid-stream urine samples collected in sterilized and capped polythene bottles, and stored in deep freezers at −20 °C till analysis. Urine samples are analysed for total arsenic and metabolites of VOCs include trans, trans-muconic acid and s-phenyl mercapturic acid (benzene metabolites), hippuric acid (toluene metabolite), mandelic acid (ethylbenzene metabolite) and methylhippuric acid (xylene metabolite). Analytical methods for toxicological analysis are presented in Table 2. To validate the toxicological assessments in participants, environmental assessments of VOCs in ambient air and arsenic in water will also be carried out. In a phased manner, exposure to other critical developmental neurotoxins, like pesticides, phthalates and polychlorinated biphenyls, will also be assessed.

Follow-up assessments

At follow-up, assessments relevant to tracking development, changes in environmental exposures, and psychopathology are done. These include – socio-demographic and migration information, environmental exposures, MINI/MINI-KID, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, ASSIST-Plus, and neuroimaging. MRI scans are repeated for those participants who underwent neuroimaging at baseline and consented for a repeat scan in follow-up. These would help track structural and functional brain growth trajectories. Blood/buccal swab samples are also collected from all consenting participants in follow-up, for epigenetic investigations.

Data analysis

Handling missing data

Attrition, difficulties in assessment within a set follow-up time frame, changes in recruitment techniques (face-to-face interviews to telephonic-based assessments), changes in reporting individuals (mother to child or vice versa), and, changes in questionnaire design are challenges in longitudinal cohorts. In cVEDA, we also have missing data from exogenous factors such as economic migration, weather catastrophes and political instability resulting in displacement of participants from one geographical area to another. These would be significant caveats to fitting longitudinal growth models for behaviour problems. “Planned missingness” improves the efficiency of longitudinal studies without compromising validity. As this missingness is by design we are able to assume that data are ‘missing completely at random’ and hence likelihood-based methods would produce unbiased effect estimates. Planned missingness can also affect the level of unplanned missingness. By reducing the number of waves of data that each participant contributes, participant-fatigue is reduced, study-dropouts are lower and, thereby, the rates of unplanned missingness.

Statistical analysis and modelling

The cVEDA will have first and foremost a descriptive analysis, as it is the first neurodevelopmental study of its kind in India with a diverse socioeconomic, geographic and cultural spread. It will present findings on key externalizing traits across the cohort with cluster analysis conducted per site to determine effects attributable to site variations. The results of cVEDA will be informed by and compared with the findings of European cohorts of children and young adults such as IMAGEN, ALSPAC, and SCAMP for behavioural traits (temperament and disorders), environmental exposures (e.g. psychosocial stressors and environmental toxins) and gene-environment interactions. Further, techniques like structural equation models [119] that estimate and converge multiple pieces of the outcome into a single latent growth or specific latent classes by age will be used to identify vulnerability factors for externalizing disorders and other mental health outcomes.

Establishment of a repository data and biobank

All cVEDA assessments are run on a digital platform using Psytools software (Delosis Ltd., UK). Data is first synchronized with the Psytools server, from where it is accessed by data management teams in India, UK and France. The final data storage server (Dell power edge R530 Rack server) is located at NIMHANS, along with a back-up safety system and a mirror data storage system in France. The data management team conducts sanity checks and feedback is regularly sent to recruitment sites.

Biological samples form part of a biobank located at NIMHANS. The databank and the biobank are a resource to facilitate research by consortium partners as well as collaborators investigating other areas of mental health, its interface with physical health, and cross-cultural comparisons.

Quality control

Quality control measures have been incorporated in the study protocol right from the beginning. Interviewer training, on-site and online, followed by mock interview assessments and feedback was conducted in the preparatory phase of the study. Following start of study on the field, India and UK based study coordinators conduct weekly recruitment meetings during which recruitment progress and completeness of data entry are reviewed. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) ensure consistency in biological samples collection and neuroimaging. Additionally, quality control procedures for neuroimaging are implemented at each site: (i) a phantom [120] is scanned to provide information about geometric distortions and signal uniformity related to hardware differences in radiofrequency coils and gradient systems, (ii) healthy volunteers are regularly scanned at each site to assess factors that cannot be measured using phantoms alone, and iii) after every subject scan, a quick 2-min script (https://github.com/cveda/cveda_mri) is run at the acquisition centre to detect any subject−/scanner-related artifacts and a decision is made if the data needs to be re-acquired. The India-based study coordinator also regular conducts site visits to monitor adherence to the study protocol.

Discussion

This paper presents the background and protocol of the cVEDA study. The study is designed to answer questions about the developmental, genomic, and environmental underpinnings of psychopathology. This has implications for preventive and early interventions for mental disorders. Biological samples collected from all participants significantly enrich exposome characterization in the sample and this will aid in discovering biomarkers of exposure and early disease through omic technologies (epigenomics, adductomics, proteomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics). Whilst it is beyond the scope of the current funding to carry out extensive omic analyses, we are establishing an integrated exposome database and biobank to facilitate future analyses. The cVEDA cohort is a substantial addition to, and provides comparative and cross-cultural datasets for international studies – IMAGEN that looks at biological and environmental factors affecting reinforcement related behaviours in teenagers; SCAMP looking at effects of mobile phone use on cognition in adolescents; ALSPAC with several decades of longitudinal data on developmental, environmental and genetic factors affecting a person’s overall health and development.

Our initial analyses have focused on establishing trajectories (behavioural, temperamental, neuropsychological) to increase our understanding of maturational brain changes and permit in-depth enquiries into the relationships between brain networks, cognition, behavior and environment during development, and how these contribute to the genesis of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Genomic DNA isolated from the buffy coat component of blood will be used for genetic studies, using next generation genotyping methods as well as genome wide epigenetic studies. RNA from samples stored in Tempus tubes will be used for transcriptome studies by arrays or RNA sequencing methods. Using statistical data reduction techniques (e.g: principal components analysis), endophenotype-genetics relationships (e.g: parallel independent component analysis), and quantitative trait loci, we will examine genetic basis of neuroimaging and neuropsychological endophenotypes.

Community engagement and capacity building

In addition to being a research initiative, cVEDA is an opportunity for community engagement. At the completion of the study we will provide a summary note to participants and an opportunity for group discussion of results, implications and treatment options, where relevant. The cVEDA consortium facilitates exchange of research, technical and statistical expertise and support with dissemination and publication of research findings via workshops and training programmes organised annually at the cVEDA investigators’ meetings at various study sites in India.

cVEDA is a first of its magnitude research exercise in India, an opportunity for research growth and capacity building. The establishment of a completely digitized data collection and transfer platform minimizes human error greatly. It also makes a large databank rapidly available to researchers working in the field. Through collaboration with institutions in the UK, research scholars also have the opportunity to partner with international researchers and faculty to build their research repertoire.

In conclusion, the cVEDA has established the largest neurodevelopmental database in India. The identification of environmental risk factors that contribute to vulnerabilities for psychiatric morbidity could have huge implications in public health interventions and prevention of psychiatric morbidity, in India. This unique database will facilitate international research collaborations, to study cross-cultural variations in the determinants of psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

Paul Elliott1, Neha Parashar2, Dhanalakshmi D2, Nayana KB2, Ashwini K Seshadri2, Sathish Kumar2, Thamodaran Arumugam3, Apoorva Safai3, Suneela Kumar Baligar4, Anthony Mary Cyril2, Aanchal Sharda3, Rashmitha4, Ashika Anne Roy3, Shivamma D2, Kiran L2, Bhavana BR2, Urvakhsh Meherwan Mehta5, Gitanjali Narayanan6, Satish Chandra Girimaji7, Amritha Gourisankar8, Geetha Rani8, Sujatha B8, Madhu Khullar9, Niranjan Khandelwal10, Nainesh Joshi10, Amit9, Debangana Bhattacharya11, Bidisha Haque11, Arpita Ghosh11, Alisha Nagraj11, Anirban Basu11, Mriganka Mouli Pandit11, Subhadip Das11, Anupa Yadav11, Surajit Das11, Sanjit Roy11, Pawan Kumar Maurya11, Ningthoujam Debala Chanu12, M C Fujica12, Ph. Victoria12, Celina Phurailatpam12, Caroline Fall13, Kiran KN14, Ramya MC14, Chaithra Urs14, Santhosh N14, Somashekhara R14, Divyashree K14, U N Arathi Rao15, Poornima R15.

1MRC Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, UK; 2Centre for Addiction Medicine, 3Department of Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, 4Molecular Genetics Laboratory, 5Department of Psychiatry, 6Department of Clinical Psychology, 7Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India; 8Rishi Valley Rural Health Centre, Madanapalle, Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, India; 9Department of Experimental Medicine, 10Department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; 11Regional Occupational Health Centre (ROHC), Eastern, ICMR-National Institute of Occupational Health (NIOH), Kolkata, West Bengal, India; 12Department of Psychiatry, Regional Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS), Imphal, Manipur, India; 13MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southamtpon, UK; 14Epidemiology Research Unit, CSI Holdsworth Memorial Hospital, Mysore, Karnataka, India; 15Division of Nutrition, St John’s Research Institute, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- ALSPAC

Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

- ASSIST

Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test Consortium on

- CD

Conduct Disorder

- cVEDA:

Vulnerability to Externalizing Disorders and Addictions

- dMRI

Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- fMRI

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- ICMR

Indian Council of Medical Research

- IMAGEN

The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology

- KCL

King’s College London

- LMIC

Low and Middle Income Countries

- MINI

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- MINI-KID

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Kids

- MRC UK

Medical Research Council, UK

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- NIMHANS

National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences

- ODD

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- rsfMRI

Resting state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- SCAMP

Study of Cognition Adolescents and Mobile Phones

- sMRI

Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- SOPs

Standard Operating Procedures

- VOCs

Volatile Organic Compounds

Author’s contributions

ES wrote the primary draft of the paper, and prepared subsequent revisions. ES, NV, UI and YZ coordinated the cVEDA study across sites in the UK and India, supervised data collection, and contributed to the methodological details in the paper. BH, RDB, GJB, and CA coordinated the neuroimaging assessments in the cVEDA study and contributed to the imaging protocols in the paper. MP, AC, SD, KamK and GK coordinated and supervised the biological sample acquisitions in the study and contributed to the methodological details in the manuscript. GSF, JH, MH and KT conceptualized the study design and drafted the relevant sections of the manuscript. PJ, MR, MT and KesK conceptualized and coordinated the behavioral and neuropsychological assessments for cVEDA. DPO and DJ set up the data acquisition pipeline and databank. PM, SJ, MV, DB, SBN, RK, SSK, KalK, MK, RLS, LRS, and KarK lead and supervise the various cVEDA recruitment sites. GS and VB conceptualized and lead the cVEDA study, and critically reviewed several drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Gunter Schumann (Centre for Population Neurosciences and Precision Medicine, IoPPN, King’s College London) and Vivek Benegal (Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore) received the Newton-Bhabha Grant for the cVEDA study, jointly funded by the Medical Research Council, UK (https://mrc.ukri.org/; Grant no. RCUK | Medical Research Council MR/N000390/1) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (https://www.icmr.nic.in/; Sanction order, letter no. ICMR/MRC-UK/3/M/2015-NCD-I). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The study protocol was peer-reviewed by both the funding bodies.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated during the cVEDA study are available to interested researchers as per the cVEDA data sharing guidelines (https://cveda.org/access-dataset/).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The cVEDA study received clearance from the Health Ministry’s Screening Committee, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, and ethics approvals at all participating centres in India and in the UK. The study also has an internal ethics advisory board that reviews any ethical issues that arise and supports recruitment centres in their operations. Participants are recruited after written informed consent. In the case of minors (<18 years of age), informed consent is taken from the legal guardian (usually parents) and assent from the child/adolescent. Consent for being contacted for follow-up is taken at the time of baseline recruitment. Consent is taken again before initiating follow-up assessments. Separate consent forms are maintained for behavioral assessments, neuroimaging and biological samples (blood, urine). Each participant recruited into the study is assigned a unique study identification number, following a ‘double anonymization’ procedure. All study data is thereby delinked from any personal identifying information. If any medical/psychosocial concerns are identified in a participant, appropriate referrals are arranged after discussion with the participant/legal guardian. All MRI scans conducted as part of the study are reviewed by a neuroradiologist. The reports are handed over to the participants/legal guardians and, when needed, appropriate neurological/neurosurgical referrals made.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eesha Sharma, Email: eesha.250@gmail.com.

Preeti Jacob, Email: preetijacob@gmail.com.

Pratima Murthy, Email: pratimamurthy@gmail.com.

Sanjeev Jain, Email: docsanjeev.jain@gmail.com.

Mathew Varghese, Email: mat.varg@yahoo.com.

Deepak Jayarajan, Email: deepak.jayarajan@gmail.com.

Keshav Kumar, Email: keshavjkapp@gmail.com.

Vivek Benegal, Email: vbenegal@gmail.com.

Nilakshi Vaidya, Email: nilakshivaidya@ymail.com.

Yuning Zhang, Email: yuning.zhang@kcl.ac.uk.

Sylvane Desrivieres, Email: sylvane.desrivieres@kcl.ac.uk.

Gunter Schumann, Email: gunter.schumann@kcl.ac.uk.

Udita Iyengar, Email: udita.iyengar@kcl.ac.uk.

Bharath Holla, Email: hollabharath@gmail.com.

Meera Purushottam, Email: meera.purushottam@gmail.com.

Amit Chakrabarti, Email: amitc@icmr.org.in.

Gwen Sascha Fernandes, Email: gwen.fernandes@bristol.ac.uk.

Jon Heron, Email: jon.heron@bristol.ac.uk.

Matthew Hickman, Email: matthew.Hickman@bristol.ac.uk.

Kamakshi Kartik, Email: kamakshi.kartik@gmail.com.

Kartik Kalyanram, Email: kartik.kalyanram@gmail.com.

Madhavi Rangaswamy, Email: madwee@gmail.com.

Rose Dawn Bharath, Email: drrosedawn@yahoo.com.

Gareth Barker, Email: gareth.barker@kcl.ac.uk.

Dimitri Papadopoulos Orfanos, Email: dimitri.papadopoulos@cea.fr.

Chirag Ahuja, Email: chiragkahuja@gmail.com.

Kandavel Thennarasu, Email: kthenna@gmail.com.

Debashish Basu, Email: db_sm2002@yahoo.com.

B. N. Subodh, Email: drsubodhbn2002@yahoo.co.in

Rebecca Kuriyan, Email: rebecca@sjri.res.in.

Sunita Simon Kurpad, Email: simonsunita@gmail.com.

Kalyanaraman Kumaran, Email: kk@mrc.soton.ac.uk.

Ghattu Krishnaveni, Email: gv.krishnaveni@gmail.com.

Murali Krishna, Email: muralidoc@gmail.com.

Rajkumar Lenin Singh, Email: leninrk@yahoo.com.

L. Roshan Singh, Email: roshandela@rediffmail.com.

Mireille Toledano, Email: m.toledano@imperial.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Census of India 2011 [Internet]. 2011; Available from: http://censusindia.gov.in

- 2.United Nations Population Fund . The state of world population 2014: adolescents, youth and the transformation of the future. New York: United Nations Population Fund; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. World Health Organization; 2009.

- 4.Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093–2102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothbart MK. Becoming who we are: temperament and personality in development. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. Temperament, environment, and psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shevlin M, McElroy E, Murphy J. Homotypic and heterotypic psychopathological continuity: a child cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(9):1135–1145. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1396-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. Schizophrenia and the neurodevelopmental continuum: evidence from genomics. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2017;16(3):227–235. doi: 10.1002/wps.20440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Brainstorm Consortium. Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395):eaap8757. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Thapar A, Craddock N. Neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(3):173–175. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Séguin JR, Leckman JF. Developmental approaches to child psychopathology: longitudinal studies and implications for clinical practice. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry J Acad Can Psychiatr Enfant Adolesc. 2013;22(1):3–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heron J, Maughan B, Dick DM, Kendler KS, Lewis G, Macleod J, et al. Conduct problem trajectories and alcohol use and misuse in mid to late adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwong ASF, Manley D, Timpson NJ, Pearson RM, Heron J, Sallis H, et al. Identifying critical points of trajectories of depressive symptoms from childhood to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(4):815–827. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0976-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frangou S, Schwarz E, Meyer-Lindenberg A. the IMAGEMEND. Identifying multimodal signatures associated with symptom clusters: the example of the IMAGEMEND project. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):179–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uher R, Zwicker A. Etiology in psychiatry: embracing the reality of poly-gene-environmental causation of mental illness. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2017;16(2):121–129. doi: 10.1002/wps.20436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychol Bull. 1977;84(2):309–322. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niedzwiecki MM, Walker DI, Vermeulen R, Chadeau-Hyam M, Jones DP, Miller GW. The exposome: molecules to populations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;59:107–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wild CP. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(1):24–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun JM, Gray K. Challenges to studying the health effects of early life environmental chemical exposures on children’s health. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(12):e2002800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timothy A, Benegal V, Lakshmi B, Saxena S, Jain S, Purushottam M. Influence of early adversity on cortisol reactivity, SLC6A4 methylation and externalizing behavior in children of alcoholics. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psychiatry. 2019;94:109649. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacka FN, Ystrom E, Brantsaeter AL, Karevold E, Roth C, Haugen M, et al. Maternal and early postnatal nutrition and mental health of offspring by age 5 years: a prospective Cohort Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(10):1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray E, Fernandes M, Fazel M, Kennedy S, Villar J, Stein A. Differential effect of intrauterine growth restriction on childhood neurodevelopment: a systematic review. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;122(8):1062–1072. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babenko O, Kovalchuk I, Metz GAS. Stress-induced perinatal and transgenerational epigenetic programming of brain development and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;48:70–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Bergh BRH, Marcoen A. High antenatal maternal anxiety is related to ADHD symptoms, externalizing problems, and anxiety in 8- and 9-year-olds. Child Dev. 2004;75(4):1085–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laslo-Baker D, Barrera M, Knittel-Keren D, Kozer E, Wolpin J, Khattak S, et al. Child neurodevelopmental outcome and maternal occupational exposure to solvents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(10):956. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauh VA, Perera FP, Horton MK, Whyatt RM, Bansal R, Hao X, et al. Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(20):7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landrigan PJ, Lambertini L, Birnbaum LS. A research strategy to discover the environmental causes of autism and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(7):a258–a260. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):330–338. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi AL, Sun G, Zhang Y, Grandjean P. Developmental fluoride neurotoxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1362–1368. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamadani JD, Tofail F, Nermell B, Gardner R, Shiraji S, Bottai M, et al. Critical windows of exposure for arsenic-associated impairment of cognitive function in pre-school girls and boys: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(6):1593–1604. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engel SM, Miodovnik A, Canfield RL, Zhu C, Silva MJ, Calafat AM, et al. Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with childhood behavior and executive functioning. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(4):565–571. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutter M, O’Connor TG, English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team Are there biological programming effects for psychological development? Findings from a study of Romanian adoptees. Dev Psychol. 2004;40(1):81–94. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chisholm K. A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Dev. 1998;69(4):1092–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–461. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S39776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John CC, Black MM, Nelson CA. Neurodevelopment: the impact of nutrition and inflammation during early to middle childhood in low-resource settings. Pediatrics. 2017;139(Supplement 1):S59–S71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2828H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Raine A, Venables PH, Mednick SA. Malnutrition at age 3 years and externalizing behavior problems at ages 8, 11, and 17 years. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2005–2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Jones L, Baban A, Kachaeva M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):641–655. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.129247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? Am J Sociol. 1993;99(2):353–395. doi: 10.1086/230268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Hickman M, Heron J, Macleod J, Lewis G, et al. Socioeconomic status and alcohol-related behaviors in mid- to late adolescence in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(4):541–545. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrison Gutman L, McLoyd VC, Tokoyawa T. Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. J Res Adolesc. 2005;15(4):425–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodes M, Tolmac J. Severely impaired young refugees. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;10(2):251–261. doi: 10.1177/1359104505051213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenkins JM, Smith MA. Marital disharmony and children’s behaviour problems: aspects of a poor marriage that affect children adversely. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991;32(5):793–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1(1):409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm. Peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol. 1999;54(9):755–764. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green KM, Musci RJ, Johnson RM, Matson PA, Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS. Outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana and alcohol use among urban young adults: a prospective study. Addict Behav. 2016;53:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward JL, Harrison K, Viner RM, Costello A, Heys M. Adolescent cohorts assessing growth, cardiovascular and cognitive outcomes in low and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moorjani P, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Lipson M, Loh P-R, Govindaraj P, et al. Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:422–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antony D. The state of the world’s children 2011-adolescence: an age of opportunity. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2011.

- 50.Gupta PC, Ray CS. Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirol Carlton Vic. 2003;8(4):419–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwok MK, Schooling CM, Lam TH, Leung GM. Does breastfeeding protect against childhood overweight? Hong Kong’s “Children of 1997” birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(1):297–305. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO|Disease and injury country estimates [Internet]. WHO2004 [cited 2018 Aug 18]; Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/

- 53.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Profile: India [Internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2010 [cited 2019 Jan 1]; Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/country_profiles/GBD/ihme_gbd_country_report_india.pdf

- 54.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fryers T, Brugha T. Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health CP EMH. 2013;9:1–50. doi: 10.2174/1745017901309010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23–33. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Dodge KA, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Child, parent, and peer predictors of early-onset substance use: a multisite longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30(3):199–216. doi: 10.1023/A:1015183927979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samokhvalov AV, Popova S, Room R, Ramonas M, Rehm J. Disability associated with alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(11):1871–1878. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, editors. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- 60.Long EC, Verhulst B, Neale MC, Lind PA, Hickie IB, Martin NG, et al. The genetic and environmental contributions to internet use and associations with psychopathology: a twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2016;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1017/thg.2015.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sartor CE, Wang Z, Xu K, Kranzler HR, Gelernter J. The joint effects of ADH1B variants and childhood adversity on alcohol related phenotypes in African-American and European-American women and men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(12):2907–2914. doi: 10.1111/acer.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benegal V, Devi M, Mukundan C, Silva M. Cognitive deficits in children of alcoholics: at risk before the first sip! Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):182. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benegal V, Jain S, Subbukrishna DK, Channabasavanna SM. P300 amplitudes vary inversely with continuum of risk in first degree male relatives of alcoholics. Psychiatr Genet. 1995;5(4):149–156. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199524000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porjesz B, Rangaswamy M, Kamarajan C, Jones KA, Padmanabhapillai A, Begleiter H. The utility of neurophysiological markers in the study of alcoholism. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(5):993–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rangaswamy M, Porjesz B, Chorlian DB, Wang K, Jones KA, Kuperman S, et al. Resting EEG in offspring of male alcoholics: beta frequencies. Int J Psychophysiol Off J Int Organ Psychophysiol. 2004;51(3):239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Venkatasubramanian G, Anthony G, Reddy US, Reddy VV, Jayakumar PN, Benegal V. Corpus callosum abnormalities associated with greater externalizing behaviors in subjects at high risk for alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2007;156(3):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hill SY, Wang S, Kostelnik B, Carter H, Holmes B, McDermott M, et al. Disruption of orbitofrontal cortex laterality in offspring from multiplex alcohol dependence families. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hill SY, Terwilliger R, McDermott M. White matter microstructure, alcohol exposure, and familial risk for alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2013;212(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PT. Reduced amygdala activation in young adults at high risk of alcoholism: studies from the Oklahoma family health patterns project. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(11):1306–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dom G, Sabbe B, Hulstijn W, van den Brink W. Substance use disorders and the orbitofrontal cortex: systematic review of behavioural decision-making and neuroimaging studies. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2005;187:209–220. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hill Shirley Y. International Review of Neurobiology. 2010. Neural Plasticity, Human Genetics, and Risk for Alcohol Dependence; pp. 53–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schweinsburg AD, Paulus MP, Barlett VC, Killeen LA, Caldwell LC, Pulido C, et al. An FMRI study of response inhibition in youths with a family history of alcoholism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:391–394. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holla B, Panda R, Venkatasubramanian G, Biswal B, Bharath RD, Benegal V. Disrupted resting brain graph measures in individuals at high risk for alcoholism. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;265:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1156–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1166–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Porjesz B, Rangaswamy M. Neurophysiological endophenotypes, CNS disinhibition, and risk for alcohol dependence and related disorders. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:131–141. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abus. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holla B, Bharath RD, Venkatasubramanian G, Benegal V. Altered brain cortical maturation is found in adolescents with a family history of alcoholism: brain CTh in familial AUDs. Addict Biol [Internet] 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 23]; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/adb.12662 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Maughan B, Stafford M, Shah I, Kuh D. Adolescent conduct problems and premature mortality: follow-up to age 65 years in a national birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2014;44(5):1077–1086. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen E, Poole TA, Nguyen V, Lerner M, Wigal T, Shannon K, et al. Prevalence of ADHD symptoms in patients with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Int Off J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2012;54(6):838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen H-J, Lee Y-J, Yeh GC, Lin H-C. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with diabetes: a population-based study. Pediatr Res. 2013;73(4 Pt 1):492–496. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuriyan R, Selvan S, Thomas T, Jayakumar J, Lokesh DP, Phillip MP, et al. Body composition percentiles in urban South Indian children and adolescents. Obesity. 2018;26(10):1629–1636. doi: 10.1002/oby.22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kuriyan R, Thomas T, Lokesh DP, Sheth NR, Mahendra A, Joy R, et al. Waist circumference and waist for height percentiles in urban South Indian children aged 3–16 years. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48(10):765–771. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krishna M, Kalyanaraman K, Veena S, Krishanveni G, Karat S, Cox V, et al. Cohort profile: the 1934–66 Mysore Birth Records Cohort in South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(6):1833–1841. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kumaran K, Fall CHD. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease and hypertension and its relevance to India. Review of evidence from the Mysore studies. 2001.

- 86.Little TD, Rhemtulla M. Planned missing data designs for developmental researchers. Child Dev Perspect. 2013;7(4):199–204. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tonry M, Ohlin LE, Farrington DP. Human development and criminal behavior. Research in criminology. New York: Springer; 1991. Accelerated longitudinal design. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012–1014. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.National Family Health Survey [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 12]; Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/index.shtml

- 90.National Sample Survey Office. Migration in India 2007–2008 [Internet]. Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India; 2010. Available from: http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/533_final.pdf

- 91.Chakrabarti A. Biomarkers and gene polymorphisms to predict association of chronic environmental organophosphorus pesticide exposure with neurodegenerative diseases: A case control study in rural West Bengal. Ahmedabad, India. 2014.

- 92.Perrin S, Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P. The Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): validity as a screening instrument for PTSD. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2005;33(4):487. doi: 10.1017/S1352465805002419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zulkifli SN, Yu SM. The food frequency method for dietary assessment. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(6):681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Buka SL, Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT. Maternal recall of pregnancy history: accuracy and bias in schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):335–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kalokhe AS, Stephenson R, Kelley ME, Dunkle KL, Paranjape A, Solas V, et al. The development and validation of the Indian family violence and control scale. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0148120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mireku MO, Mueller W, Fleming C, Chang I, Dumontheil I, Thomas MSC, et al. Total recall in the SCAMP cohort: validation of self-reported mobile phone use in the smartphone era. Environ Res. 2018;161:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Newcomb MD, Huba GJ, Bentler PM. A multidimensional assessment of stressful life events among adolescents: derivation and correlates. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(4):400. doi: 10.2307/2136681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frick PJ. Alabama parenting questionnaire. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frick PJ, Christian RE, Wootton JM. Age trends in the association between parenting practices and conduct problems. Behav Modif. 1999;23(1):106–128. doi: 10.1177/0145445599231005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.West M, Rose MS, Spreng S, Sheldon-Keller A, Adam K. Adolescent attachment questionnaire: a brief assessment of attachment in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1998;27(5):661–673. doi: 10.1023/A:1022891225542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol. 1979;52(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001;72(5):1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Capaldi DM, Rothbart MK. Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. J Early Adolesc. 1992;12(2):153–173. doi: 10.1177/0272431692012002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Developing a model for adult temperament. J Res Pers. 2007;41(4):868–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The big five inventory – versions 4a and 54. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Goodman R, Meltzer H, Bailey V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;7(3):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):313–326. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.WHO ASSIST Working Group The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gearhardt AN, Roberto CA, Seamans MJ, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale for children. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52(2):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Gentile DA. The internet gaming disorder scale. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(2):567–582. doi: 10.1037/pas0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, Naveen Kumar C, Mahadevaiah M, Rao K, Subbakrishna DK, et al. Validation of Social Cognition Rating Tools in Indian Setting (SOCRATIS): A new test-battery to assess social cognition. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(3):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hernández-Avila M, Smith D, Meneses F, Sanin LH, Hu H. The influence of bone and blood lead on plasma lead levels in environmentally exposed adults. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(8):473–477. doi: 10.1289/ehp.106-1533211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Smith D, Hernandez-Avila M, Téllez-Rojo MM, Mercado A, Hu H. The relationship between lead in plasma and whole blood in women. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(3):263–268. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Muthen BO. Second-generation structural equation modeling with a combination of categorical and continuous latent variables: new opportunities for latent class/latent growth modeling. In: Collins LM, Sayer A, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 291–322. [Google Scholar]

- 120.McCollough CH, Bruesewitz MR, McNitt-Gray MF, Bush K, Ruckdeschel T, Payne JT, et al. The phantom portion of the American College of Radiology (ACR) Computed Tomography (CT) accreditation program: Practical tips, artifact examples, and pitfalls to avoid. Med Phys. 2004;31(9):2423–2442. doi: 10.1118/1.1769632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lejuez C. W., Read Jennifer P., Kahler Christopher W., Richards Jerry B., Ramsey Susan E., Stuart Gregory L., Strong David R., Brown Richard A. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2002;8(2):75–84. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Logan Gordon D., Cowan William B. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A theory of an act of control. Psychological Review. 1984;91(3):295–327. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during the cVEDA study are available to interested researchers as per the cVEDA data sharing guidelines (https://cveda.org/access-dataset/).