Abstract

The composition, density, diversity, and temporal distribution of mosquito species and the influence of temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall on these data were investigated in 50 sites across five land cover classes (forest, savannah, barren, village, and agriculture) in southeastern Senegal. Mosquitoes were collected monthly in each site between June 2009 and March 2011, with three people collecting mosquitoes landing on their legs for one to four consecutive days. In total, 81,219 specimens, belonging to 60 species and 7 genera, were collected. The most abundant species were Aedes furcifer (Edwards) (Diptera: Culicidae) (20.7%), Ae. vittatus (Bigot) (19.5%), Ae. dalzieli (Theobald) (14.7%), and Ae. luteocephalus (Newstead) (13.7%). Ae. dalzieli, Ae. furcifer, Ae. vittatus, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae. taylori Edwards, Ae. africanus (Theobald), Ae. minutus (Theobald), Anopheles coustani Laveran, Culex quinquefasciatus Say, and Mansonia uniformis (Theobald) comprised ≥10% of the total collection, in at least one land cover. The lowest species richness and Brillouin diversity index (HB = 1.55) were observed in the forest-canopy. The urban-indoor fauna showed the highest dissimilarity with other land covers and was most similar to the urban-outdoor fauna following Jaccard and Morisita index. Mosquito abundance peaked in June and October 2009 and July and October 2010. The highest species density was recorded in October. The maximum temperature was correlated positively with mean temperature and negatively with rainfall and relative humidity. Rainfall showed a positive correlation with mosquito abundance and species density. These data will be useful for understanding the transmission of arboviruses and human malaria in the region.

Keywords: biodiversity, land cover class, mosquitoes, arbovirus, malaria

Mosquitoes are among the animals with the highest medical and veterinary impact because they transmit many arboviruses, protozoa, helminths, and bacteria that cause significant human and animal morbidity and mortality (Peters 1992, Service 1993, Gubler 2009). In Senegal, particularly in the southeast, mosquitoes are vectors of many arboviruses of medical and veterinary importance (dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika, West Nile, and Rift Valley fever) and of human malaria (Monlun et al. 1993; Fontenille et al. 1998; Diallo et al. 1999, 2003; Dia et al. 2003, 2008; Faye et al. 2007). In addition to the known pathogenic arboviruses, many other viruses for which the potential to harm human and animal health is not yet known (Ngari, Kédougou, etc.) have been isolated from mosquitoes in the area (Monlun et al. 1993, Zeller et al. 1996). Moreover, this region is experiencing substantial environmental changes driven by uncontrolled industrial gold mining. Indeed, this activity has led to an exponential increase of the human population and consequently an increase in the destruction and fragmentation of natural environments (forest galleries and savannah) within these environments. In the long term, this transformation of natural habitats due to human activities is likely to decrease mosquito species diversity (Thongsripong et al. 2013, Young et al. 2017, Mangudo et al. 2018) and leads to a loss of sylvatic mosquito species that will not be able to adapt to artificial breeding habitats. At the outset, however, this accelerating transformation will probably increase the number of sylvatic mosquito populations frequenting human environments at the edge of the forest-galleries and may change sylvatic arbovirus transmission patterns (Patz and Reisen 2001, Patz et al. 2004, Richman et al. 2018). Deforestation, agriculture, urban development, and human encroachment into previously undisturbed areas have been suggested to be catalysts for changes in vector community composition and the introduction of new pathogens (Hayes et al. 1996, Conn et al. 2002, Cox et al. 2007).

Since 1972, several entomoepidemiological studies have been conducted in Kédougou, the southeastern region of Senegal with the main objective being to conduct surveillance on arboviruses and malaria and, to a lesser extent, to conduct bioecological studies of their vectors (Monlun et al. 1993; Traore-Lamizana et al. 1994; Traoré-Lamizana et al. 1996; Fontenille et al. 1998; Diallo et al. 1999, 2003, 2012a,b, 2014a,b; Faye et al. 2007; Dia et al. 2008). Data from these studies were leveraged to model the distribution and transmission of Aedes-borne viruses and their main vectors (Althouse et al. 2012, 2015, 2018; Richman et al. 2018). However, little is known about mosquito biodiversity per se in the region or about the impact of environmental factors on such biodiversity in this focus of sylvatic arbovirus transmission. A better understanding of these parameters is essential for predicting the distribution and dynamics of vector-borne diseases, understanding their epidemiology, and developing and implementing effective vector control measures.

Our primary goal in this project was to characterize the spatial and temporal biodiversity of mosquitoes in Kédougou and to determine the impact of environmental factors on biodiversity. This paper is an extension of our previous studies in the area, using pooled mosquito data collected and presented partially in Diallo et al. (2012b, 2014b) and analyzed, here, using biodiversity indices and tools.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

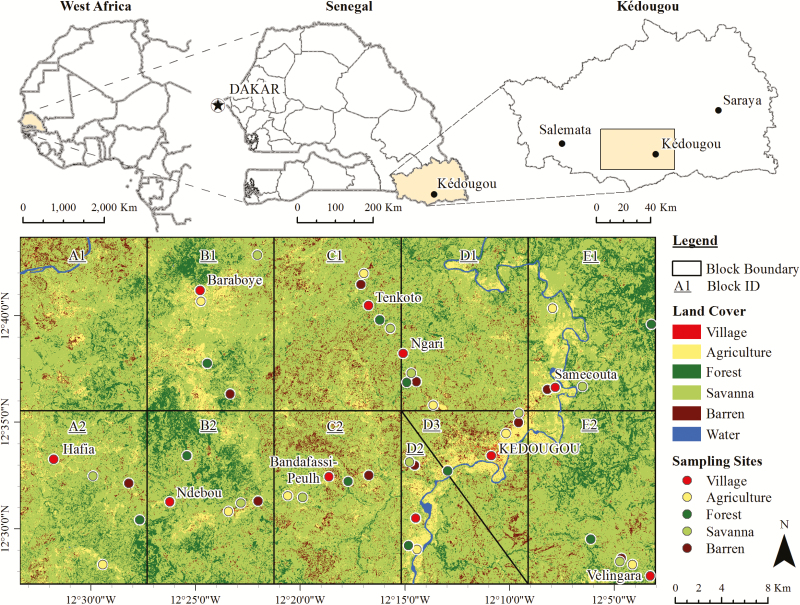

The study was conducted in the Kédougou region of southeastern Senegal (central coordinates: 12°33′ N, 12°11′ W) at the borders of Mali and Guinea (Fig. 1, slightly modified from Diallo et al. 2012b). This area was described in detail previously (Diallo et al. 2012b). Briefly, the area has mainly six land cover classes. Villages, representing <5% of the area, are sites composed mostly of a mixture of dwellings (most of them with mud walls and thatched roofs) and roads. Agricultural land encompasses mostly croplands (e.g., maize, peanuts, rice, fonio, millet, and sorghum fields) and pastures. Forests are densely wooded areas with Combretum glutinosum, Bombax costatum, Cordyla pinnata, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Terminalia macroptera, Oxythenantera abyssinica being among the most common tree species, and other species like Saba senegalensis being much more localized. Savannas are sparsely wooded grasslands. Barren lands are areas in which less than one-third of the landscape has vegetation or other cover and are typically characterized by exposed soil or rocks. Finally, water in the study area is limited to the Gambia River, which runs through much of the eastern portion of the study area.

Fig. 1.

Study area in Kédougou, Senegal. This figure is modified from Diallo et al. (2012b).

The Kédougou region is hilly, with mean annual temperatures varying between 33 and 40°C and about 1,200 mm of annual rainfall. The area has one rainy season, generally from June to October. The natural environment of the area is being transformed by agricultural, gold mining, and other human activities. Despite the recent increase of the population due to the gold mining activities, the region is still rural with a low density of inhabitants of 9/km2. Some human activities in the area such as farming and hunting bring people in contact with the forest. Mining camps have been created near gold veins, which are often located close to or even within the forests.

Mosquito Sampling

The mosquito data used in this paper are those collected and presented partially in Diallo et al. (2012b, 2014b). Mosquito sampling site selection, description, and sampling schemes were thoroughly described in earlier papers (Diallo et al. 2012b, 2014b; Richman et al. 2018). Briefly, mosquitoes were collected in an area of 1,650 km2 (30 km in N-S direction; 55 km in E-W direction) from June 2009 to March 2011 (except April 2010) in 50 sites belonging to 5 land cover classes (forest, barren, savannah, agriculture, and urban) identified by remote sensing and geospatial analyses. Mosquitoes were collected monthly in each site from 6–9 PM using human landing catches. In savannah, agriculture, and barren lands, teams of three collectors were positioned at ground level. In forests, two teams of three collectors each were positioned at ground level and on platforms in the canopy. In urban areas (villages), two teams of three collectors each were installed indoors and outdoors. All landing collectors participated in informed oral consent. They were provided malaria prophylaxis, monitored for signs of febrile illness, and provided any medical treatment needed. Mosquitoes were identified using external morphology via didactic keys (Ferrara et al. 1984, Diagne et al. 1994, Jupp 1997, Edwards 1941).

Weather Data

Daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperature, rainfall, and relative humidity data, representative of the study area, were obtained from the Kédougou Aerodrome weather station (12°34’0″ N, 12°13’0″ W). This station is located 5 km north-west of Kédougou city. These data were used to calculate mean monthly maximum, minimum, and mean temperature, rainfall, and relative humidity values. We obtained weather data from May 2009 (1 mo prior to the beginning of the study) to consider possible lagged responses of mosquito populations to these weather elements.

Data Analysis

Mosquito biodiversity was measured using the species density (Sd; number of collected species in each habitat), species richness (Sr; estimated number of species in each habitat given equal sample sizes), and the Brillouin diversity indices (HB). The species density is the number of observed species. Individual-based rarefaction curves were used to estimate and compare spatial and temporal species richness (Sr) (Gotelli and Colwell 2001). Rarefaction-based estimates and 95% CIs were computed with the software Analytical Rarefaction 1.3 (Holland 2003). The Brillouin diversity index is a measure of the proportion of individuals of each species in each community and incorporates relative abundance of collected specimens to estimate species diversity. This index is preferred when the randomness of a sample (data from human landing catches here, with species representation based on differential attraction to men) cannot be guaranteed (Magurran 2004).

The similarity between environments was evaluated using the Morisita index (IM) for quantitative data and the Jaccard index (IJ) for qualitative data (Magurran 2004). These indices and 95% CIs were obtained using the program PAST, version 2.14 (Hammer et al. 2001). Dominance was calculated according to the formula: D (%) = (i/t) × 100, where i denotes total of individuals of the species and t denotes total of individuals collected and clustered following the categories established by Friebe (1983): eudominant D ≥ 10%, dominant 10% > D ≥ 5%, subdominant 5% > D ≥ 2%, eventual 2% > D ≥ 1%, and rare D < 1%. Proportions of rare species and singletons between land cover classes were compared by the χ2 test. To test influences of selected weather variables on the abundance of mosquitoes, the Spearman’s rank correlation test was employed using data from the meteorological station of the Kédougou Aerodrome. Influences of weather variables on mosquito abundance were tested using weather measurements taken concurrent with collection and with measurements taken 1 mo previous to the collection. The Spearman’s rank correlation test was used because the mean temperature and rainfall data were not normally distributed and were not rendered normal via data transformation. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team 2017).

Results

In total, 81,219 mosquitoes belonging to the subfamilies Culicinae (91.6% of the total) and Anophelinae (8.4% of the total) was collected over the course of the two study seasons (Table 1). Aedes, Anopheles, and Mansonia genera accounted for 84.7, 8.4, and 5.3% of the specimens captured, respectively. The remaining genera (Culex, Uranotaenia, Toxorhynchites, and Eretmapodites) comprised <3.0% of the specimens. The most abundant species, presented in Table 2, were Aedes furcifer (Edwards) (20.7% of the total collection), Aedes vittatus (Bigot) (19.5%), Aedes dalzieli (Theobald) (14.7%), and Aedes luteocephalus (Newstead) (13.7%). It was possible to identify 60 species belonging to the genera Aedes (25), Anopheles (16), Culex (14), Mansonia (02), Eretmapodites (01), Uranotaenia (01), and Toxorhynchites (01). Only six species occurred in relative abundance above 5%, totaling >4,000 individuals collected; 7 had abundances between 1 and 4%. The remaining 47 species occurred in relative abundance <1%, from which five were represented by only two individuals (doubletons) and four by only one specimen (singletons).

Table 1.

Mosquito abundance by genus and subfamily in specified land cover classes, Kédougou; data from June 2009 through Mar. 2010 and May 2010 through Mar. 2011 combined

| Genera/ Subfamily | Agriculture | Barren | Savannah | Forest-canopy | Forest-ground | Urban-outdoor | Urban-indoor | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Aedes | 11,681 | 72.20 | 11,039 | 83.62 | 10,954 | 78.70 | 14,497 | 97.95 | 12,619 | 90.23 | 6,571 | 91.04 | 1,441 | 75.21 | 68,802 | 84.71 |

| Anopheles | 1,728 | 10.68 | 1,322 | 10.01 | 2,364 | 16.98 | 106 | 0.72 | 806 | 5.76 | 315 | 4.36 | 165 | 8.61 | 6,806 | 8.38 |

| Culex | 167 | 1.03 | 154 | 1.17 | 107 | 0.77 | 137 | 0.93 | 120 | 0.86 | 307 | 4.25 | 286 | 14.93 | 1,278 | 1.57 |

| Eretmapodites | 7 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.01 | 7 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.05 | 21 | 0.03 |

| Mansonia | 2,594 | 16.03 | 685 | 5.19 | 490 | 3.52 | 60 | 0.41 | 433 | 3.10 | 25 | 0.35 | 22 | 1.15 | 4,309 | 5.31 |

| Toxorhynchites | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Uranotaenia | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.05 | 2 | 0.00 | |||||

| Culicinae | 14,450 | 89.32 | 11,880 | 89.99 | 11,555 | 83.02 | 14,695 | 99.28 | 13,179 | 94.24 | 6,903 | 95.64 | 1,751 | 91.39 | 74,413 | 91.62 |

| Anophelinae | 1,728 | 10.68 | 1,322 | 10.01 | 2,364 | 16.98 | 106 | 0.72 | 806 | 5.76 | 315 | 4.36 | 165 | 8.61 | 6,806 | 8.38 |

| Total | 16,178 | 100 | 13,202 | 100 | 13,919 | 100 | 14,801 | 100 | 13,985 | 100 | 7,218 | 100 | 1,916 | 100 | 81,219 | 100 |

No., number of mosquitoes collected.

Table 2.

Mosquito abundance and dominance category by species and land cover class in Kédougou; data from June 2009 through Mar. 2010 and May 2010 through Mar. 2011 combined

| Species | Agriculture | Barren | Savannah | Forest-canopy | Forest-ground | Urban-outdoor | Urban-indoor | Total | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | No. | % | DC | ||

| Aedes aegypti | 97 | 0.6 | Ra | 43 | 0.3 | Ra | 97 | 0.7 | Ra | 29 | 0.2 | Ra | 247 | 1.8 | Ev | 305 | 4.2 | Sd | 55 | 2.9 | Sd | 873 | 1.1 | Ev | |

| Aedes africanus | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 1,485 | 10 | Ed | 773 | 5.5 | do | 1 | 0 | Ra | 2,263 | 2.8 | Sd | |||||||

| Aedes argenteopunctatus | 381 | 2.4 | Sd | 455 | 3.4 | Sd | 298 | 2.1 | Sd | 11 | 0.1 | Ra | 44 | 0.3 | Ra | 90 | 1.2 | Ev | 4 | 0.2 | Ra | 1,283 | 1.6 | Ev | |

| Aedes bromeliae | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aedes centropuctatus | 89 | 0.6 | Ra | 65 | 0.5 | Ra | 43 | 0.3 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 40 | 0.3 | Ra | 7 | 0.1 | Ra | 246 | 0.3 | Ra | ||||

| Aedes cozi | 1 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 8 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Aedes cumminsii | 106 | 0.7 | Ra | 24 | 0.2 | Ra | 26 | 0.2 | Ra | 65 | 0.5 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 224 | 0.3 | Ra | |||||||

| Aedes dalzieli | 3,842 | 23.7 | Ed | 2,304 | 17.5 | Ed | 3,001 | 21.6 | Ed | 130 | 0.9 | Ra | 1,813 | 13 | Ed | 672 | 9.3 | do | 169 | 8.8 | do | 11,931 | 14.7 | Ed | |

| Aedes fowleri | 42 | 0.3 | Ra | 41 | 0.3 | Ra | 26 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 16 | 0.1 | Ra | 23 | 0.3 | Ra | 7 | 0.4 | Ra | 156 | 0.2 | Ra | |

| Aedes furcifer | 2,008 | 12.4 | Ed | 2,432 | 18.4 | Ed | 2,523 | 18.1 | Ed | 4,089 | 27.6 | Ed | 2,169 | 15.5 | Ed | 3,068 | 42.5 | Ed | 545 | 28.4 | Ed | 16,834 | 20.7 | Ed | |

| Aedes hirsutus | 50 | 0.3 | Ra | 31 | 0.2 | Ra | 26 | 0.2 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 11 | 0.1 | Ra | 27 | 0.4 | Ra | 5 | 0.3 | Ra | 153 | 0.2 | Ra | |

| Aedes longipalpis | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aedes luteocephalus | 205 | 1.3 | Ev | 235 | 1.8 | Ev | 547 | 3.9 | Sd | 6,208 | 41.9 | Ed | 3,750 | 26.8 | Ed | 125 | 1.7 | Ev | 40 | 2.1 | Sd | 11,110 | 13.7 | Ed | |

| Aedes mcintoshi | 117 | 0.7 | Ra | 78 | 0.6 | Ra | 28 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 6 | 0 | Ra | 11 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 242 | 0.3 | Ra | |

| Aedes metallicus | 93 | 0.6 | Ra | 80 | 0.6 | Ra | 76 | 0.5 | Ra | 27 | 0.2 | Ra | 71 | 0.5 | Ra | 22 | 0.3 | Ra | 2 | 0.1 | Ra | 371 | 0.5 | Ra | |

| Aedes minutus | 1,021 | 6.3 | do | 454 | 3.4 | Sd | 463 | 3.3 | Sd | 51 | 0.3 | Ra | 1,236 | 8.8 | do | 666 | 9.2 | do | 207 | 10.8 | Ed | 4,098 | 5 | do | |

| Aedes mixtus | 5 | 0 | Ra | 8 | 0.1 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 8 | 0.1 | Ra | 24 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Aedes neoafricanus | 1 | 0 | Ra | 6 | 0 | Ra | 81 | 0.5 | Ra | 34 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 123 | 0.2 | Ra | |||||||

| Aedes ochraceus | 14 | 0.1 | Ra | 43 | 0.3 | Ra | 11 | 0.1 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 75 | 0.1 | Ra | |||||||

| Aedes opok | 4 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aedes soudanensis | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aedes taylori | 53 | 0.3 | Ra | 92 | 0.7 | Ra | 151 | 1.1 | Ev | 2,133 | 14.4 | Ra | 340 | 2.4 | Sd | 20 | 0.3 | Ra | 4 | 0.2 | Ra | 2,793 | 3.4 | Sd | |

| Aedes unilineatus | 21 | 0.1 | Ra | 43 | 0.3 | Ra | 49 | 0.4 | Ra | 8 | 0.1 | Ra | 23 | 0.2 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0.1 | Ra | 149 | 0.2 | Ra | |

| Aedes vexans | 3 | 0 | Ra | 5 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 6 | 0.1 | Ra | 15 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Aedes vittatus | 3,531 | 21.8 | Ed | 4,610 | 34.9 | Ed | 3,568 | 25.6 | Ed | 230 | 1.6 | Ev | 1,967 | 14.1 | Ed | 1,516 | 21 | Ed | 400 | 20.9 | Ed | 15,822 | 19.5 | Ed | |

| Anopheles brohieri | 3 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 13 | 0 | Ra | |||||||

| Anopheles brunnipes | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anopheles coustani | 1,241 | 7.7 | do | 882 | 6.7 | do | 1,593 | 11.4 | Ed | 29 | 0.2 | Ra | 325 | 2.3 | Sd | 85 | 1.2 | Ev | 29 | 1.5 | Ev | 4,184 | 5.2 | do | |

| Anopheles domicola | 10 | 0.1 | Ra | 18 | 0.1 | Ra | 22 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 7 | 0.1 | Ra | 9 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 68 | 0.1 | Ra | |

| Anopheles flavicosta | 18 | 0.1 | Ra | 39 | 0.3 | Ra | 60 | 0.4 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 12 | 0.1 | Ra | 5 | 0.1 | Ra | 136 | 0.2 | Ra | ||||

| Anopheles freetownensis | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anopheles funestus s.l. | 191 | 1.2 | Ev | 193 | 1.5 | Ev | 358 | 2.6 | Sd | 10 | 0.1 | Ra | 147 | 1.1 | Ev | 65 | 0.9 | Ra | 35 | 1.8 | Ev | 999 | 1.2 | Ev | |

| Anopheles gambiae s.l. | 84 | 0.5 | Ra | 34 | 0.3 | Ra | 34 | 0.2 | Ra | 7 | 0 | Ra | 32 | 0.2 | Ra | 63 | 0.9 | Ra | 64 | 3.3 | Sd | 318 | 0.4 | Ra | |

| Anopheles hancocki | 22 | 0.1 | Ra | 29 | 0.2 | Ra | 70 | 0.5 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 12 | 0.1 | Ra | 6 | 0.1 | Ra | 141 | 0.2 | Ra | ||||

| Anopheles nili s.l. | 96 | 0.6 | Ra | 65 | 0.5 | Ra | 134 | 1 | Ra | 50 | 0.3 | Ra | 237 | 1.7 | Ev | 56 | 0.8 | Ra | 26 | 1.4 | Ev | 664 | 0.8 | Ra | |

| Anopheles pharoensis | 11 | 0.1 | Ra | 8 | 0.1 | Ra | 6 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0.1 | Ra | 34 | 0 | Ra | |

| Anopheles pretoriensis | 1 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||||||||

| Anopheles rufipes | 23 | 0.1 | Ra | 17 | 0.1 | Ra | 31 | 0.2 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 5 | 0 | Ra | 8 | 0.1 | Ra | 5 | 0.3 | Ra | 91 | 0.1 | Ra | |

| Anopheles squamosus | 2 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 6 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 13 | 0 | Ra | |||||||

| Anopheles wellcomei | 14 | 0.1 | Ra | 28 | 0.2 | Ra | 48 | 0.3 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 21 | 0.2 | Ra | 5 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 118 | 0.1 | Ra | |

| Anopheles ziemanni | 12 | 0.1 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 21 | 0 | Ra | |||||||

| Culex annulioris | 13 | 0.1 | Ra | 6 | 0 | Ra | 22 | 0.2 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 11 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 54 | 0.1 | Ra | ||||

| Culex antennatus | 19 | 0.1 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 5 | 0.1 | Ra | 37 | 0 | Ra | ||||

| Culex bitaeniorhynchus | 12 | 0.1 | Ra | 7 | 0.1 | Ra | 48 | 0.3 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 17 | 0.1 | Ra | 87 | 0.1 | Ra | |||||||

| Culex cinerellus | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Culex cinerus | 3 | 0.2 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Culex decens | 2 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 5 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Culex ethiopicus | 5 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 10 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Culex macfiei | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||||||||

| Culex neavei | 12 | 0.1 | Ra | 5 | 0 | Ra | 6 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 30 | 0 | Ra | ||||

| Culex nebulosus | 90 | 0.7 | Ra | 3 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 96 | 0.1 | Ra | ||||||||||

| Culex perfuscus | 8 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 13 | 0.1 | Ra | 55 | 0.4 | Ra | 58 | 0.4 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 140 | 0.2 | Ra | |

| Culex poicilipes | 90 | 0.6 | Ra | 26 | 0.2 | Ra | 5 | 0 | Ra | 59 | 0.4 | Ra | 20 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 201 | 0.2 | Ra | ||||

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 6 | 0 | Ra | 10 | 0.1 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 297 | 4.1 | Sd | 276 | 14.4 | Ed | 594 | 0.7 | Ra | |

| Culex tritaeniorhynchus | 4 | 0 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 3 | 0.2 | Ra | 18 | 0 | Ra | ||||

| Eretmapodites quinquevittatus | 7 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 4 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | 7 | 0.1 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 21 | 0 | Ra | ||||

| Mansonia africana | 717 | 4.4 | Sd | 116 | 0.9 | Ra | 171 | 1.2 | Ev | 23 | 0.2 | Ra | 131 | 0.9 | Ra | 25 | 0.3 | Ra | 10 | 0.5 | Ra | 1,193 | 1.5 | Ev | |

| Mansonia uniformis | 1,877 | 11.6 | Ed | 569 | 4.3 | Sd | 319 | 2.3 | Sd | 37 | 0.2 | Ra | 302 | 2.2 | Sd | 12 | 0.6 | Ra | 3,116 | 3.8 | Sd | ||||

| Toxorhynchites brevipalpis | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0 | Ra | |||||||||||||||||||

| Uranotaenia mayeri | 1 | 0 | Ra | 1 | 0.1 | Ra | 2 | 0 | Ra | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 16,178 | 100 | 13,202 | 100 | 13,919 | 100 | 14,801 | 100 | 13,985 | 100 | 7,218 | 100 | 1916 | 100 | 81,219 | 100 | |||||||||

No., number of mosquitoes collected; DC, dominance categories; Ed, eudominant; Do, dominant; Sd, subdominant; Ev, eventual; Ra, rare

Total mosquito abundance was highest in agriculture (16,178 individuals/19.9% of all catches), followed by forest-canopy (14,801/18.2%), forest-ground (13,985/17.2%) and savannah (13,919/17.1%), which were extremely similar, barren (13,202/16.3%), urban-outdoor (7,218/8.9 %), and urban-indoor land covers (1,916/2.4%).

Those species occurring at ≥10% (hereafter termed eudominant) were Ae. dalzieli (23.7% of the total collection), Ae. furcifer (21.8%), Ae. vittatus (12.4%) and Ma. uniformis (Theobald) (11.6%) in agriculture; Ae. vittatus (34.9%), Ae. furcifer (18.4%) and Ae. dalzieli (17.4%) in barren; Ae. luteocephalus (41.9%), Ae. furcifer (27.6%), Ae. taylori Edwards (14.4%) and Ae. africanus (Theobald) (10.0%) in forest-canopy; Ae. luteocephalus (26.8 %), Ae. furcifer (15.5 %), Ae. vittatus (14.1%) and Ae. dalzieli (13.0%) in forest-ground; Ae. vittatus (25.6%), Ae. dalzieli (21.6%), Ae. furcifer (18.1%) and Anopheles coustani Laveran (11.4%) in savannah; Ae. furcifer (28.4%), Ae. vittatus (20.9%), Culex quinquefasciatus Say (14.4%), and Aedes minutus (Theobald) (10.8%) in urban-indoor; and Ae. furcifer (42.1%) and Ae. vittatus (20.8%) in urban-outdoor. Together, these highly dominant species represented 69.6, 70.8, 94.0, 69.3, 76.8, 74.5, and 63.0% of the total abundance of agriculture, barren, forest-canopy, forest-ground, savannah, urban-indoor, and urban-outdoor respectively. Twenty-five of the sixty species (41.7%) were shared among all land cover classes. The proportions of rare species, representing <1% of the mosquito fauna (Table 3) were statistically comparable among land cover classes (χ2 = 7.2; df = 6; P = 0.3), whereas the proportions of singletons were significantly different (χ2 = 17.3; df = 6; P = 0.008). The highest proportion of species represented by a singleton was observed in the urban-indoor followed by the forest-canopy, urban-outdoor, savannah, forest-ground, agriculture and barren.

Table 3.

Mosquito diversity in different land cover classes, Kédougou data from June 2009 through Mar. 2010 and May 2010 through Mar. 2011 combined

| Agriculture | Barren | Savannah | Forest-canopy | Forest-ground | Urban-outdoor | Urban-indoor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB | 2.29a | 2.11c | 2.21b | 1.55e | 2.28a | 1.87d | 2.1c |

| (CI) | (2.27–2.30) | (2.08–2.13) | (2.19–2.23) | (1.53–1.56) | (2.26–2.30) | (1.84–1.90) | (2.04–2.14) |

| Species density | 48 | 45 | 50 | 44 | 46 | 42 | 34 |

HB with different letters are significantly different.

HB, Brillouin diversity indices; CI, confidence intervals of the Brillouin diversity indices.

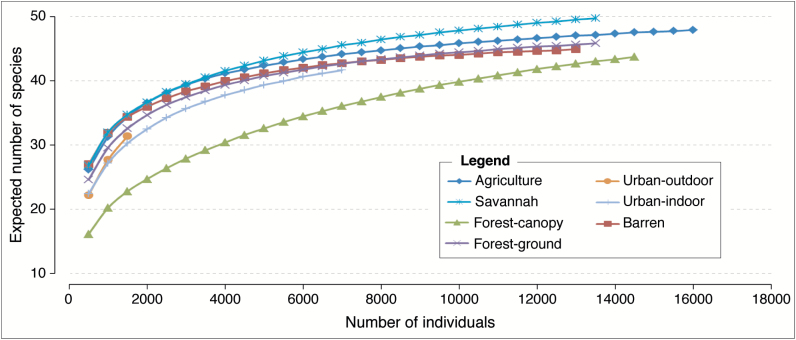

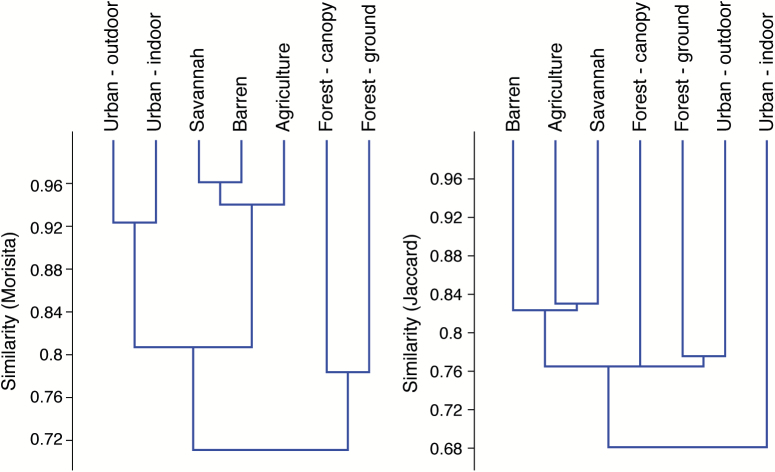

The highest species density was observed in the savannah (Sd = 50), followed by agriculture (Sd = 48), forest-ground (Sd = 46), barren (Sd = 45), forest-canopy (Sd = 44), urban-outdoor (Sd = 42), and urban-indoor (Sd = 34) land covers (Table 4). Individual-based rarefaction curves (Fig. 2) suggested that, for equal sample sizes, the lowest species richness (Sr) was observed in the forest-canopy. The lowest Brillouin diversity index was observed in the forest-canopy (HB = 1.55) and urban-outdoor (HB = 1.87) indicated higher skew in relative abundance of different species in these land covers (Table 4). The savannah, agriculture, and barren land covers were the most similar according to the Jaccard index (Fig. 3), whereas the urban-indoor showed the highest dissimilarity among land covers. The Morisita index showed three clusters of similarity composed of the savannah, barren, and agricultural land covers (1); the urban-indoor and urban-outdoor (2); and forest-canopy and forest-ground (3).

Table 4.

Diversity categories of mosquito species collected by human landing catch in different land cover classes in Kédougou, June 2009 through Mar. 2010 and May 2010 through Mar. 2011

| Diversity categories | Land cover classes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Barren | Forest-canopy | Forest-ground | Savannah | Urban-indoor | Urban-outdoor | ||||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Eudominant | 4 | 8.3 | 3 | 6.7 | 3 | 6.8 | 4 | 8.7 | 4 | 8.0 | 4 | 11.8 | 2 | 4.8 |

| Dominant | 2 | 4.2 | 1 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 4.8 | ||

| Subdominant | 2 | 4.2 | 3 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.5 | 5 | 10.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 4.8 | |

| Eventual | 2 | 4.2 | 2 | 4.4 | 1 | 2.3 | 3 | 6.5 | 2 | 4.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 7.1 |

| Rare | 38 | 79.2 | 36 | 80.0 | 40 | 90.9 | 34 | 73.9 | 38 | 76.0 | 23 | 67.6 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Singleton | 4 | 8.3 | 3 | 6.7 | 10 | 22.7 | 4 | 8.7 | 5 | 10.0 | 11 | 32.3 | 7 | 16.7 |

| Total species | 48 | 100 | 45 | 100 | 44 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 42 | 100 |

Fig. 2.

Individual-based rarefaction curves for mosquitoes collected in different land cover classes, Kédougou, Senegal during June 2009 through March 2010 and May 2010 through March 2011.

Fig. 3.

Cluster analysis using the Morisita and Jaccard indexes between land cover classes in Kédougou, June 2009 through March 2010 and May 2010 through March 2011.

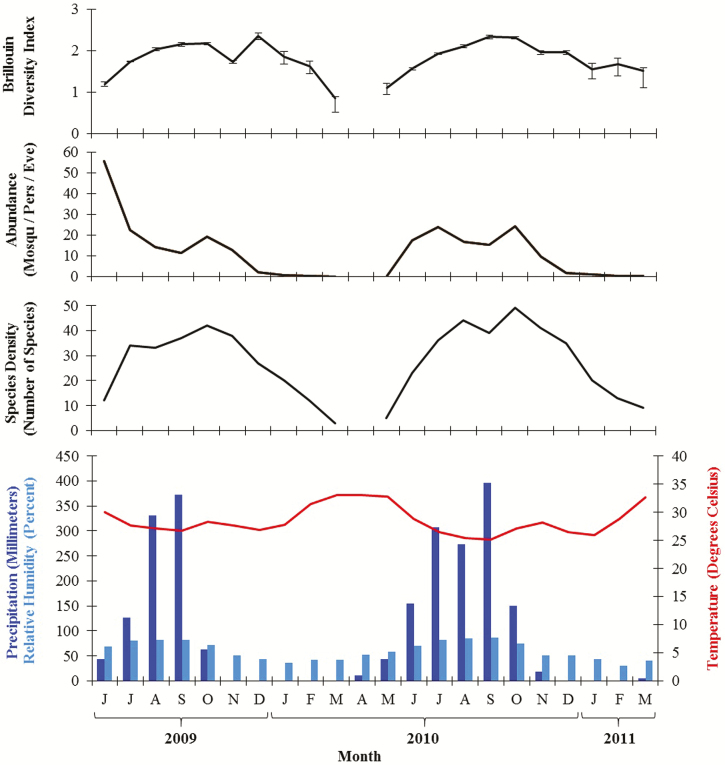

Summing across all land covers, peak mosquito abundances were observed in June and October 2009 and July and October 2010. The highest species densities were recorded in October 2009 and 2010 with 42 and 49 species, respectively (Fig. 4). December had the highest Brillouin diversity index in 2009, whereas September and October had the highest Brillouin index in 2010.

Fig. 4.

Monthly distribution of mosquito diversity indices, mean temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and rainfall (mm) in Kédougou, June 2009 through March 2010 and May 2010 through March 2011. Error bars in the Brillouin diversity indices indicate 95% confidence intervals. Abundance is measured as mean number of mosquitoes collected per person per evening.

Figure 4 presents weather data (temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall) obtained from the Kédougou Aerodrome station. August and September were the wettest months in 2009, whereas July and September were wettest in 2019. Temperatures peaked in March in 2010 and 2011 and reached their nadir in January 2009, 2010, and 2011 and December 2009 and 2010. The maximum temperature was positively and significantly correlated with mean temperature (rho = 0.8; P < 0.0001) and negatively and significantly correlated with rainfall (rho = −0.8; P < 0.0001) and relative humidity (rho = −0.8; P < 0.0001). Rainfall and relative humidity showed a strong positive and significant correlation (rho = 0.9; P < 0.0001). Rainfall showed a positive and significant correlation with mosquito abundance (rho = 0.8; P < 0.0001) and species density (rho = 0.6; P = 0.007). Moreover, correlations between rainfall and abundance of mosquitoes were higher after a lag time of a month (rho = 0.9; P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Largely due to the fact that the geographical scope of this study was broader and that a higher number of human collectors were used, we collected more mosquito species than all previously reported studies using human landing collection in the Kédougou region (Cornet et al. 1978, Traoré-Lamizana et al. 1996, Diallo et al. 2003, Dia et al. 2005). However, the 60 mosquito species detected in the current study are fewer than the 102 species previously reported from this area by four sampling methods (human landing catch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-light traps supplemented with dry ice, CDC-light traps located in sheepfolds, and animal + light-baited traps) over a longer period (Fontenille et al. 1998). Our study showed the presence and dominance of the Aedes spp. that are vectors of sylvatic DENV, CHIKV, ZIKV, and YFV in forest galleries and villages in southeastern Senegal. This predominance of Aedes was reported previously by several others for the Kédougou region using human landing catch alone (Cornet et al. 1978, Traore-Lamizana et al. 1994, Diallo et al. 2003) or associated with other sampling methods (Fontenille et al. 1998). We also observed for the first time the dominance of these vector species in three major land covers in the study area (savannah, barren, and agriculture), thus supporting the widespread risk for transmission of viruses carried by these mosquitoes.

Our findings also revealed important differences in mosquito species diversity among land cover classes, as shown by other investigations in Africa (Muturi et al. 2006), Asia (Thongsripong et al. 2013, Young et al. 2017, Mangudo et al. 2018), and the Americas (Yanoviak et al. 2006, Johnson et al. 2008). Aedes furcifer, a known vector of DENV, CHIKV, ZIKV, and YFV in the region (Traore-Lamizana et al. 1994, Traoré-Lamizana et al. 1996, Diallo et al. 1999, Boyer et al. 2018), was the only species eudominant in all land cover classes investigated, thus corroborating its role in the epidemiology of these viruses. This species has been responsible for the most important outbreaks of enzootic yellow fever in Africa and also has been reported as the only abundant and YFV-infected species in villages, and is, thus, considered a likely bridge vector of this arbovirus to humans (Salaun et al. 1981, Baudon et al. 1984, Cordellier 1991, Diallo et al. 2014b).

The results of our study also indicated that the eudominant mosquito species varied according to the land cover class, a pattern that may be driven by larval development, adult feeding, and/or resting habitats of each species, or both. Culex quinquefasciatus, for example, was eudominant only indoors in urban settings and Ma. uniformis only in agriculture. The eudominance of Cx. quinquefasciatus in the urban-indoors is not surprising, as it exhibits highly anthropophilic and endophilic behavior in West Africa and oviposits in anthropogenic polluted water rich in organic matter (Subra 1981). Mansonia uniformis is eudominant in areas of agriculture surrounded by temporary marshes, which serve as the larval habitats for this species when they are covered by hygrophytes at the end of the rainy season (Wharton 1962, Apiwathnasorn et al. 2006). All of the eudominant species in agriculture and urban-indoor environments have been associated with several arboviruses of medical and/or veterinary importance, including Rift valley fever, West Nile, and Zika viruses (Fontenille et al. 1998; Diallo et al. 2005, 2014a; Boyer et al. 2018).

The forest-canopy contained the lowest mosquito diversity, whereas the forest-ground and agriculture contained the highest diversity. The low diversity in the canopy compared with the ground level was similar to the results of an equivalent study in Latin America (Juliao et al. 2010). The higher diversity of forest-ground mosquito community compared with the more urbanized environments was also observed by others in Thailand, Malaysian Borneo, and Argentina (Thongsripong et al. 2013, Young et al. 2017, Mangudo et al. 2018). Spatial and seasonal variation in mosquito biodiversity is known to result from the variation of several abiotic and biotic parameters, including temperature, relative humidity, rainfall, larval and resting habitat, and bloodmeal sources (Bates 1949, Yanoviak 1999). The lower mosquito diversity in the forest-canopy as compared with the forest-ground is discordant with the higher amount and diversity of vertebrate hosts living in the canopy (Erwin 2001, de Thoisy et al. 2003, Haugaasen and Peres 2007). It is likely that this pattern is driven by the low diversity of larval and resting habitats in the forest-canopy as compared with the other landscapes. Indeed, only tree-holes are available as larval habitats for mosquitoes in the canopy; thus, mainly tree-hole mosquitoes (Ae. furcifer, Ae. africanus, and Ae. luteocephalus) may be found host-seeking in the canopy. Larval habitat availability and diversity may also explain why the mosquito diversity was higher between August and December when all the larval habitat types generally contain water in Kédougou (Raymond et al. 1976, Diallo et al. 2012a).

Among the anophelines, we collected specimens belonging to the Anopheles gambiae complex and Anopheles funestus and Anopheles nili groups in the forest and savannah land covers. This was surprising because the only known members of these complex or groups of species in the Kédougou area are highly anthropophilic species (An. gambiae s.s., Anopheles arabiensis, An. funestus, and An. nili), usually found in domestic environments, and incriminated in the transmission of malaria in Southeastern Senegal (Dia et al. 2003, 2005). Confirmation of the identity of these sylvatic populations of An. gambiae s.l., An. funestus s.l., and An. nili s.l. must be confirmed with genetic analyses, because they are known to belong to species groups with different epidemiological importance. Indeed, An. gambiae s.l is a complex of at least eight species (An. gambiae, Anopheles coluzzi, Anopheles arabiensis, Anopheles melas, Anopheles merus, Anopheles bwambae, Anopheles quadriannulatus A and B), An. funestus s.l. is a group of 11 species (An. funestus s.s., An. funestus-like, Anopheles rivulorum, Anopheles vaneedeni, Anopheles leesoni, Anopheles confusus, Anopheles fuscivenosus, Anopheles brucei, Anopheles parensis, Anopheles aruni, and An. rivulorum-like), and An. nili s.l. is a group of four species (An. nili s.s., Anopheles somalicus, Anopheles carnevalei, and Anopheles ovengensis). Of these, only An. gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis, An. funestus, and An. nili are considered important malaria vectors in Africa (Fontenille and Simard 2004). If the sylvatic populations are the same species and are found infected, this finding would complicate malaria elimination and eradication strategies, because when these mosquitoes could move between sylvatic and domestic environments. This pattern was reported in South America, where forest dwelling An. cruzii and An. fluminensis are believed to transmit malaria to people by migrating from the forest to human dwellings for blood-feeding and then returning to the forest (Forattini et al. 2000).

The high number of rare species (N = 47) found in this study was probably due to the low effectiveness of human landing collections for some species as well as diurnal variation in activity among species. Indeed, some of these species are collected more efficiently by larval sampling, CDC-light traps, or sheep-baited traps in the study area (Raymond et al. 1976, Fontenille et al. 1998, Diallo et al. 2012a). Moreover, our sampling was limited to the evening, the period when the Anopheles species are not very active. These species are known to seek blood-meals later during the night. Additionally, some rare species may have very low population abundance due to highly specific and unstable larval habitats.

In conclusion, this study describes for the first time the biodiversity of mosquitoes in a focus of sylvatic arbovirus activity. Diversity of mosquito species varied substantially according to the land cover classes, the period of the collection, and weather variables. Species known to be vectors of arboviruses were eudominant in all the landscapes investigated, suggesting a high risk of arboviral diseases emergence as human populations continue to grow and to intrude upon sylvatic environments in the Kédougou region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Saliou Ba, Momar Tall, and Bidiel Fall for their technical assistance in the field and all the population of Kédougou for their collaboration. Financial support for mosquito collections was provided by the National Institutes of Health (grant RO1AI069145).

References Cited

- Althouse B. M., Lessler J., Sall A. A., Diallo M., Hanley K. A., Watts D. M., Weaver S. C., and Cummings D. A.. 2012. Synchrony of sylvatic dengue isolations: a multi-host, multi-vector SIR model of dengue virus transmission in Senegal. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 6: e1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althouse B. M., Hanley K. A., Diallo M., Sall A. A., Ba Y., Faye O., Diallo D., Watts D. M., Weaver S. C., and Cummings D. A.. 2015. Impact of climate and mosquito vector abundance on sylvatic arbovirus circulation dynamics in Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92: 88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althouse B. M., Guerbois M., Cummings D. A. T., Diop O. M., Faye O., Faye A., Diallo D., Sadio B. D., Sow A., Faye O., et al. 2018. Role of monkeys in the sylvatic cycle of chikungunya virus in Senegal. Nat. Commun. 9: 1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apiwathnasorn C., Samung Y., Prummongkol S., Asavanich A., and Komalamisra N.. 2006. Surveys for natural host plants of Mansonia mosquitoes inhabiting Toh Daeng peat swamp forest, Narathiwat Province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 37: 279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates M. 1949. The natural history of mosquitoes. Macmillian Company; New York: . 379 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Baudon D., Robert V., Roux J., Stanghellini A., Gazin P., Molez J. F., Lhuillier M., Sartholi J. L., Saluzzo J. F., and Cornet M.. 1984. Epidemic yellow fever in Upper Volta. Lancet. 2: 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer S., Calvez E., Chouin-Carneiro T., Diallo D., and Failloux A. B.. 2018. An overview of mosquito vectors of Zika virus. Microbes Infect. 01: 006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn J. E., Wilkerson R. C., Segura M. N., de Souza R. T., Schlichting C. D., Wirtz R. A., and Póvoa M. M.. 2002. Emergence of a new neotropical malaria vector facilitated by human migration and changes in land use. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordellier R. 1991. [The epidemiology of yellow fever in Western Africa]. Bull. World Health Organ. 69: 73–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornet M., Robin Y., Heme G., and Valade M.. 1978. [Isolation in east Senegal of a yellow fever virus strain from a pool of Aedes belonging to the subgenus Diceromyia]. C. R. Acad. Sci. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. D. 287: 1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Grillet M. E., Ramos O. M., Amador M., and Barrera R.. 2007. Habitat segregation of dengue vectors along an urban environmental gradient. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76: 820–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dia I., Diop T., Rakotoarivony I., Kengne P., and Fontenille D.. 2003. Bionomics of Anopheles gambiae Giles, An. arabiensis Patton, An. funestus Giles and An. nili (Theobald) (Diptera: Culicidae) and transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in a Sudano-Guinean zone (Ngari, Senegal). J. Med. Entomol. 40: 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dia I., Diallo D., Duchemin J. B., Ba Y., Konate L., Costantini C., and Diallo M.. 2005. Comparisons of human-landing catches and odor-baited entry traps for sampling malaria vectors in Senegal. J. Med. Entomol. 42: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dia I., Konate L., Samb B., Sarr J. B., Diop A., Rogerie F., Faye M., Riveau G., Remoue F., Diallo M., et al. 2008. Bionomics of malaria vectors and relationship with malaria transmission and epidemiology in three physiographic zones in the Senegal River Basin. Acta Trop. 105: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagne N., Fontenille D., Konate L., Faye O., Lamizana M. T., Legros F., Molez J. F., and Trape J. F.. 1994. [Anopheles of Senegal. An annotated and illustrated list]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 87: 267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo M., Thonnon J., Traore-Lamizana M., and Fontenille D.. 1999. Vectors of Chikungunya virus in Senegal: current data and transmission cycles. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60: 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo M., Ba Y., Sall A. A., Diop O. M., Ndione J. A., Mondo M., Girault L., and Mathiot C.. 2003. Amplification of the sylvatic cycle of dengue virus type 2, Senegal, 1999-2000: entomologic findings and epidemiologic considerations. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9: 362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo M., Nabeth P., Ba K., Sall A. A., Ba Y., Mondo M., Girault L., Abdalahi M. O., and Mathiot C.. 2005. Mosquito vectors of the 1998-1999 outbreak of Rift Valley Fever and other arboviruses (Bagaza, Sanar, Wesselsbron and West Nile) in Mauritania and Senegal. Med. Vet. Entomol. 19: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo D., Diagne C. T., Hanley K. A., Sall A. A., Buenemann M., Ba Y., Dia I., Weaver S. C., and Diallo M.. 2012a. Larval ecology of mosquitoes in sylvatic arbovirus foci in southeastern Senegal. Parasit. Vectors. 5: 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo D., Sall A. A., Buenemann M., Chen R., Faye O., Diagne C. T., Faye O., Ba Y., Dia I., Watts D., et al. 2012b. Landscape ecology of sylvatic chikungunya virus and mosquito vectors in southeastern Senegal. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 6: e1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo D., Sall A. A., Diagne C. T., Faye O., Faye O., Ba Y., Hanley K. A., Buenemann M., Weaver S. C., and Diallo M.. 2014a. Zika virus emergence in mosquitoes in southeastern Senegal, 2011. PLoS One. 9: e109442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo D., Sall A. A., Diagne C. T., Faye O., Hanley K. A., Buenemann M., Ba Y., Faye O., Weaver S. C., and Diallo M.. 2014b. Patterns of a sylvatic yellow fever virus amplification in southeastern Senegal, 2010. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90: 1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards F. 1941. Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian region: III Culicine adults and pupae. British Museum (Natural History), London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin T. L. 2001. Forest canopies, animal diversity, pp. 19–25. InLevin S. A. (ed.), Encyclopedia of biodiversity, vol. 3 Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Faye O., Diallo M., Dia I., Ba Y., Faye O., Mondo M., Sylla R., Faye P. C., and Sall A. A.. 2007. [Integrated approach to yellow fever surveillance: pilot study in Senegal in 2003-2004]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 100: 187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara L., Germain M., and Hervy J. P.. 1984. Aedes (Diceromyia) furcifer (Edwards, 1913) et Aedes (Diceromyia) taylori (Edwards, 1936): le point sur la différentiation des adultes. Cahier ORSTOM Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie. 22: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fontenille D., and Simard F.. 2004. Unravelling complexities in human malaria transmission dynamics in Africa through a comprehensive knowledge of vector populations. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27: 357–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenille D., Traore-Lamizana M., Diallo M., Thonnon J., Digoutte J. P., and Zeller H. G.. 1998. New vectors of Rift Valley fever in West Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4: 289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forattini O. P., Kakitani I., dos Santos R. l. C., Kobayashi K. M., Ueno H. M., and Fernández Z.. 2000. Potencial sinantrópico de mosquitos Kerteszia e Culex (Diptera: Culicidae) no Sudeste do Brasil. Revista de Saúde Pública 34: 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebe B. 1983. Zur Biologie eines Buchenwaldbodens: 3 Die Käferfauna. Carolinea, Karlsruhe 41: 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli N. J., and Colwell R. K.. 2001. Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 4: 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. J. 2009. Vector-borne diseases. Rev. Sci. Tech. 28: 583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø., Harper D. A. T., and Ryan P. D.. 2001. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4: 1– 9. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaasen T., and Peres C.. 2007. Vertebrate responses to fruit production in Amazonian flooded and unflooded forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 16: 4165–4190. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C. G., Phillips I. A., Callahan J. D., Griebenow W. F., Hyams K. C., Wu S. J., and Watts D. M.. 1996. The epidemiology of dengue virus infection among urban, jungle, and rural populations in the Amazon region of Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S. M. 2003. Analytic Rarefaction 1.3 computer program, version By Holland, S. M. http://www.uga.edu/strata/software/anRareReadme.html [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. F., Gómez A., and Pinedo-Vasquez M.. 2008. Land use and mosquito diversity in the Peruvian Amazon. J. Med. Entomol. 45: 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julião G. R., Abad-Franch F., Lourenço-De-Oliveira R., and Luz S. L.. 2010. Measuring mosquito diversity patterns in an Amazonian terra firme rain forest. J. Med. Entomol. 47: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp P. G. 1997. Mosquitoes of southern Africa: culicinae and Toxorhynchitinae. Ekogilde cc Publishers, Hartebeespoort, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran A. E. 2004. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Publishing, Maldan, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Mangudo C., Aparicio J. P., Rossi G. C., and Gleiser R. M.. 2018. Tree hole mosquito species composition and relative abundances differ between urban and adjacent forest habitats in northwestern Argentina. Bull. Entomol. Res. 108: 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monlun E., Zeller H., Le Guenno B., Traoré-Lamizana M., Hervy J. P., Adam F., Ferrara L., Fontenille D., Sylla R., and Mondo M.. 1993. [Surveillance of the circulation of arbovirus of medical interest in the region of eastern Senegal]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 86: 21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muturi E. J., Shililu J., Jacob B., Gu W., Githure J., and Novak R.. 2006. Mosquito species diversity and abundance in relation to land use in a riceland agroecosystem in Mwea, Kenya. J. Vector Ecol. 31: 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patz J. A., and Reisen W. K.. 2001. Immunology, climate change and vector-borne diseases. Trends Immunol. 22: 171–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patz J. A., Daszak P., Tabor G. M., Aguirre A. A., Pearl M., Epstein J., Wolfe N. D., Kilpatrick A. M., Foufopoulos J., Molyneux D., et al. ; Working Group on Land Use Change and Disease Emergence. 2004. Unhealthy landscapes: policy recommendations on land use change and infectious disease emergence. Environ. Health Perspect. 112: 1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. 1992. A colour atlas of arthropods in clinical medicine. Wolfe Publishing, London, United Kingdom: 304 pp. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R. 2017. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: https://www.Rproject.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Raymond H., Cornet M., and Dieng P. Y.. 1976. Etudes sur les vecteurs sylvatiques du virus amaril. Inventaire provisoire des habitats larvaires d’une forêt-galerie dans le foyer endémique du Sénégal Oriental. Cahier ORSTOM Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie. 14: 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Richman R., Diallo D., Diallo M., Sall A. A., Faye O., Diagne C. T., Dia I., Weaver S. C., Hanley K. A., and Buenemann M.. 2018. Ecological niche modeling of Aedes mosquito vectors of chikungunya virus in southeastern Senegal. Parasit. Vectors. 11: 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaun J. J., Germain M., Robert V., Robin Y., Monath T. P., Camicas J. L., and Digoutte J. P.. 1981. [Yellow fever in Senegal from 1976 to 1980 (author’s transl)]. Med. Trop. (Mars). 41: 45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service M. W. 1993. Mosquitoes (Culicidae), pp. 120–240. InLane R. P. and Crosskey R. W. (eds.), Medical insects and Arachnids. Chapman & Hall, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Subra R. 1981. Biology and control of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus, Say, 1823 (Diptera: Culicidae) with special reference to Africa. Insect Sci. Appl. 4: 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- de Thoisy B., Gardon J., Salas R. A., Morvan J., and Kazanji M.. 2003. Mayaro virus in wild mammals, French Guiana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9: 1326–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongsripong P., Green A., Kittayapong P., Kapan D., Wilcox B., and Bennett S.. 2013. Mosquito vector diversity across habitats in central Thailand endemic for dengue and other arthropod-borne diseases. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 7: e2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traore-Lamizana M., Zeller H., Monlun E., Mondo M., Hervy J. P., Adam F., and Digoutte J. P.. 1994. Dengue 2 outbreak in southeastern Senegal during 1990: virus isolations from mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 31: 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traoré-Lamizana M., Fontenille D., Zeller H. G., Mondo M., Diallo M., Adam F., Eyraud M., Maiga A., and Digoutte J. P.. 1996. Surveillance for yellow fever virus in eastern Senegal during 1993. J. Med. Entomol. 33: 760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton R. H. 1962. The biology of Mansonia mosquitoes in relation to the transmission of filariasis in Malaya. Bull. Inst. Med. Res. Kuala Lumpur. 11: 1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanoviak S. P. 1999. Community structure in water-filled tree holes of Panama: effects of hole height and size. Selbyana. 20: 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yanoviak S. P., Paredes J. E., Lounibos L. P., and Weaver S. C.. 2006. Deforestation alters phytotelm habitat availability and mosquito production in the Peruvian Amazon. Ecol. Appl. 16: 1854–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. I., Mundis S., Widen S. G., Wood T. G., Tesh R. B., Cardosa J., Vasilakis N., Perera D., and Hanley K. A.. 2017. Abundance and distribution of sylvatic dengue virus vectors in three different land cover types in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. Parasit. Vectors. 10: 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller H. G., Diallo M., Angel G., Traoré-Lamizana M., Thonnon J., Digoutte J. P., and Fontenille D.. 1996. [Ngari virus (Bunyaviridae: Bunyavirus). First isolation from humans in Senegal, new mosquito vectors, its epidemiology]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 89: 12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]