SUMMARY

The canonical cortical microcircuit has principally been defined by interlaminar excitatory connections among the six layers of the neocortex. However, excitatory neurons in layer 6 (L6), a layer whose functional organization is poorly understood, form relatively rare synaptic connections with other cortical excitatory neurons. Here, we show that the vast majority of parvalbumin inhibitory neurons in a sublamina within L6 send axons through the cortical layers toward the pia. These interlaminar inhibitory neurons receive local synaptic inputs from both major types of L6 excitatory neurons and receive stronger input from thalamocortical afferents than do neighboring pyramidal neurons. The distribution of these interlaminar interneurons and their synaptic connectivity further support a functional subdivision within the standard six layers of the cortex. Positioned to integrate local and long-distance inputs in this sublayer, these interneurons generate an inhibitory interlaminar output. These findings call for a revision to the canonical cortical microcircuit.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Frandolig et al. show that the neuronal composition and circuit organization differs between two distinct sublayers in layer 6a. Interlaminar parvalbumin inhibitory interneurons represent the major inhibitory interneuron in upper layer 6a, integrate local and thalamocortical inputs, and contribute an interlaminar inhibitory projection to the canonical cortical microcircuit.

INTRODUCTION

Interlaminar excitatory feedforward projections among the 6 layers of the neocortex have largely defined the canonical cortical microcircuit: the middle cortical layer, layer 4 (L4), is the main thalamorecipient layer, and information is then sent via excitatory projections to layers 2/3 (L2/3) and then to layers 5 and 6 (L5 and L6), the main cortical output layers (Adesnik and Naka, 2018; Bastos et al., 2012; Douglas and Martin, 2004; Feldmeyer, 2012; Harris and Mrsic-Flogel, 2013). Most cortical inhibition is generated locally within a layer (Dantzker and Callaway, 2000; Feldmeyer et al., 2018; Kätzel et al., 2011). However, it has become increasingly clear that inhibitory effects between layers affect the cortical response, only some of which are mediated by classic sources of interlaminar inhibition: dendrite-targeting somatostatin inhibitory neurons and the subset of layer 1 (L1) inhibitory neurons that send axons into the deeper layers (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Kapfer et al., 2007; Kätzel et al., 2011; Muñoz et al., 2017; Naka et al., 2019; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Pluta et al., 2015; Schuman et al., 2019; Silberberg and Markram, 2007; Xu et al., 2016).

Unlike excitatory neurons in other cortical layers, excitatory projection neurons (PNs) in L6, one of the least-well-understood cortical layers (Briggs, 2010; Thomson, 2010), are notable for infrequently synapsing onto other PNs (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Beierlein et al., 2003; Cotel et al., 2018; Crandall et al., 2017; Lee and Sherman, 2009; Lefort et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2005; Schubert et al., 2003; Seeman et al., 2018; Tarczy-Hornoch et al., 1999; West et al., 2006). L6 also contains inhibitory interneurons (INH INs), about half of which express parvalbumin (PV) (Lee et al., 2010; Perrenoud et al., 2013), typical of fast-spiking (FS) INH INs. Morphological reconstructions indicate that the axons of most L6 FS INH INs ramify locally, but some send axons toward L1 (Arzt et al., 2018; Bortone et al., 2014; Kumar and Ohana, 2008). L6 INH INs are thought to receive preferential input from L6 corticothalamic neurons (CThNs), one of the two major types of L6 PNs (West et al., 2006). This privileged relation is hypothesized to contribute to the modulation of the cortical response to sensory input by L6 CThNs, generating the broad cortical inhibition following the activation of L6 CThNs in vivo mediated by local and interlaminar projections of PV INs (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Williamson and Polley, 2019), and is thought to distinguish L6 CThNs from the other major class of L6 PNs, L6 corticocortical neurons (CCNs) (Thomson, 2010).

Using mouse whisker-associated somatosensory cortex (barrel cortex) as a model, we show that two sublayers within layer 6a (L6a), separate from layer 6b (L6b) (Feldmeyer, 2012; Hoerder-Suabedissen et al., 2009), have distinct INH INs and circuit organization. Interlaminar PV INs (IL-PV INs), which send axons toward the pia, are restricted to upper L6a (L6U), while the axons of PV INs in lower L6a (L6L) ramify locally. We find that neither type of PV IN receives preferential input from L6 CThNs. Although facilitation is considered a defining feature of L6 CThN synapses onto thalamocortical (TC) (Crandall et al., 2015; Deschênes and Hu, 1990; Jackman et al., 2016; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Turner and Salt, 1998) and cortical neurons within (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; West et al., 2006) and outside L6 (Ferster and Lindström, 1985; Stratford et al., 1996), the synapses of L6L CThNs onto local PV INs depress. The organization of synaptic inputs onto L6U IL-PV INs indicates that they integrate both TC and local excitatory inputs. Combined with the weak connectivity of L6 PNs with other excitatory cortical neurons (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Beierlein et al., 2003; Lee and Sherman, 2009; Lefort et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2005; Schubert et al., 2003; Seeman et al., 2018; Tarczy-Hornoch et al., 1999; West et al., 2006), our results suggest that these IL-PV INs form an interlaminar inhibitory output contributing to the canonical cortical microcircuit.

RESULTS

Parvalbumin Interneurons Segregate into Two Sublayers in L6a of the Somatosensory Cortex

PV FS INH INs represent approximately half of the INH INs in the infragranular layers of the mouse barrel cortex (Lee et al., 2010; Perrenoud et al., 2013). Prior studies of the rat barrel cortex identified two types of FS INs, one with axons in L6 and one with axons ramifying primarily in L4 (Kumar and Ohana, 2008). In mouse visual cortex, FS INs with axons extending to the supragranular layers have been described, although the axons of most FS INs branch locally (Bortone et al., 2014). To assess the morphological diversity of PV INs in L6 of mouse barrel cortex, we first analyzed the distribution of PV INs in L6.

We found that the number of PV INs was higher in L6U than in L6L (Figures 1A and 1B). This difference in the vertical distribution of PV INs was recapitulated in a transgenic mouse line (Gad1-GFP, G42 line) in which GFP is selectively expressed in a subset of PV INs (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2004) (Figures 1A and 1B). This difference in the distribution of PV INs in L6a may, in part, reflect an overall decrease in the cell density in deeper L6a (Meyer et al., 2011). There were even fewer PV INs in L6b, a distinct layer with neurons that express connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (Heuer et al., 2003) and do not express Cre recombinase in Ntsr1-Cre mice (Figure S1). Next, we filled L6a GFP+ INs of Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato;Gad1-GFP mice with biocytin and revealed the morphology of 197 PV INs. We identified PV INs with axons primarily within L6 (local PV INs; Figure 1C). The axons of many PV INs, however, exited the infragranular layers and extended toward L1 (IL-PV INs; Figures 1D and 1E).

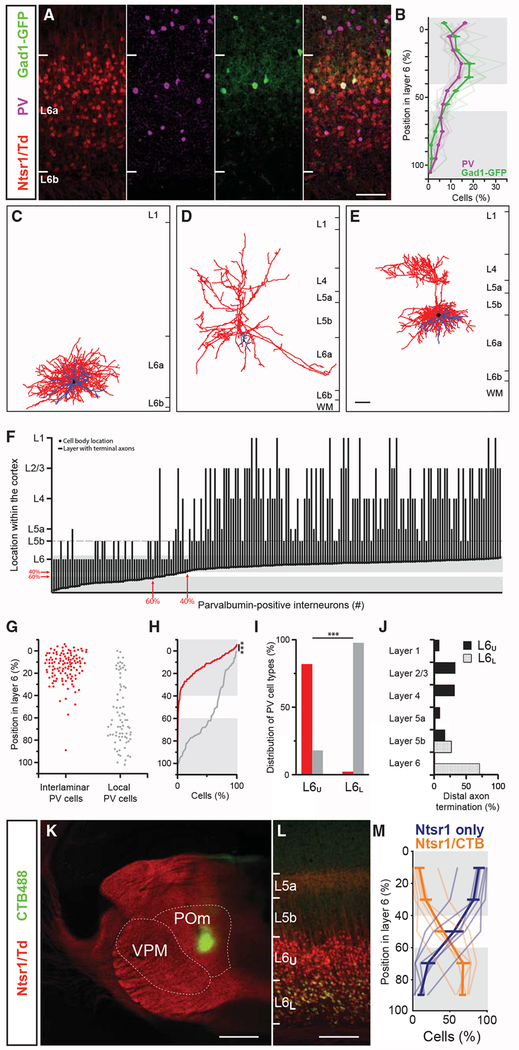

Figure 1. Interlaminar Parvalbumin Interneurons (IL-PV INs) Are Restricted to a Sublamina in Upper Layer 6a.

(A) Confocal images of L6 corticothalamic neurons (CThNs) identified by Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato expression (red, far left), parvalbumin interneurons (PV INs) identified with antibodies to PV (purple, left), or GFP expression in a Gad1-GFP mouse line (G42 line) in which GFP is selectively expressed in PV INs (green, right) in barrel cortex, overlaid in the far-right panel.

(B) Distribution of PV+ and GFP+ INs in L6 (n = 9 slices from 2 mice). Gray shading highlights regions above 40% (L6U) and below 60% (L6L) of the vertical extent of L6a, between which comparisons were made (number of PV INs in L6U, top gray region: 64.9% ± 1.5% and L6L, bottom gray region: 20.2% ± 1.4%; p < 0.0039, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; number of GFP INs in L6U, top gray region: 67.8% ± 0.4% and L6L, bottom gray region: 12.1% ± 1.1%, p < 0.0039, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

(C–E) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a PV IN with locally ramifying axons (C) and two PV INs with interlaminar-projecting axons (D and E). Axons in red, dendrites in blue, and cell bodies in black.

(F) Plot showing the soma location and layer containing the distal terminal axons of morphologically identified PV INs (n = 195). The red arrows indicate depths of 40% and 60% in L6a (y axis) and cell body locations of the PV INs most closely positioned to these depths (x axis). L6U and L6L were defined based on the proportion of local PV and IL-PV INs and are indicated by the gray shading.

(G) Summary data showing the soma location of each IL-PV (red) and local PV IN (gray) in L6a.

(H) Cumulative distribution in L6a of the soma location of IL-PV (red) and local (gray) PV INs (p = 2.8 × 10−19; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

(I) Percentage of PV INs with interlaminar or local morphology in L6U (n = 139) and L6L (n = 44; p = 6.46 × 10 −23, Fisher’s exact test).

(J) Laminar location of the distal-most axonal process for neurons in L6U (n = 139, black) and L6L (n = 44, stippled; p < 0.00001, chi-square test).

(K) Low-magnification view of an injection of retrograde tracer (green, Alexa 488 cholera toxin B [CTB]; Alexa 488 CTB) into the posterior medial nucleus (POm) of the thalamus of an Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mouse.

(L) Image of the barrel cortex showing L6 CThNs that project to the ventral posterior medial nucleus (VPM) of the thalamus (red, VPM-only L6 CThNs) and L6 CThNs that project to VPM and the POm (yellow, VPM/POm L6 CThNs).

(M) Distribution of VPM-only (Ntsr1) and VPM/POm (Ntsr1/CTB) L6 CThNs in L6a of the barrel cortex (n = 6 slices from 4 mice). Gray shading highlights L6U and L6L as defined by the distribution of IL-PV and local PV INs.

Scale bars, 100 μm in (A), (C)–(E), and (L); 500 μm in (K).

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Next, we asked whether both types of L6a PV INs were found through the vertical extent of L6a. We found that the axonal pattern of L6a PV INs correlated with their soma location (Figure 1F). All but one PV IN with axons reaching into L5a or above were located in L6U (Figures 1F and 1G). In contrast, the majority of local PV INs were found in L6L (Figures 1F–1H). At a depth of ≥60%, 98% of the morphologically identified PV INs were local PV INs. In the transition zone, from 40% to 60% of L6a, 29% of the PV INs were IL-PV INs (Figure 1F, between the red arrows). From 40% to 30% of the depth of L6a, IL-PV INs represented 50% of the morphologically identified PV INs, a proportion that further increased in the top of L6a. Based on the proportions of these two types of PV INs through the vertical extent of L6a, we designated L6U as the top 40% of L6a (L6U), where IL-PV INs predominate, and L6L as the bottom 40% (L6L), where local PV INs represented all but one morphologically identified PV IN (Figures 1B, 1F, and 1H).

Using these designations for L6U and L6L, we found that 82% of the L6U PV INs were IL-PV INs (114 of 139 neurons; Figure 1I). The most pial extent of the intracortical axons of L6U IL-PV INs primarily terminated in L4 and L2/3 (Figure 1J). Approximately 35% of the IL-PV INs (39 of 114 IL-PV neurons) had axonal processes that densely arborized within the middle layers of barrel cortex, like the cell in Figure 1E. For many IL-PV INs, we found processes ramifying locally in L6U as well as extending into L6L. By estimating the horizontal extent of IL-PV INs, we found that <5% of IL-PV INs had axonal arbors <300 μm wide (5 of 108 IL-PV INs). Most of the cells had axons that extended for at least 300–900 μm (78%; 84 of 108 IL-PV INs), and some cells had identifiable axons spanning ≥900 μm (18%; 19 of 108 IL-PV INs). Thus, IL-PV INs are not confined to single barrels, which span approximately 150 μm; rather, many have axons that extend for hundreds of microns horizontally and vertically in the cortex.

In contrast to L6U, 98% of the biocytin-filled L6L PV INs were local INs with axonal processes confined to L6 and L5b (Figure 1I; 43 of 44 PV INs). The proportion of IL-PV and local PV INs was significantly different between L6U and L6L (Figure 1I). The laminar location of the most distal terminations of the axons was also significantly different between L6U IL-PV and L6L local PV INs (Figure 1J). Like IL-PV INs, the axons of most local PV INs extended horizontally beyond the confines of a single overlying L4 barrel: 73% (30 of 41) had axons that extended at least 300–900 μm horizontally, while only 2% (1 of 41) extended <300 μm horizontally. Twenty-four percent (10 of 41) had detectable axons that extended ≥900 μm. Thus, the horizontal extent of L6U IL-PV and L6L local PV INs was similar, although the vertical extent of their axonal arbors differed significantly.

IL-PV and local PV INs not only had strikingly different morphologies but also their electrophysiological characteristics differed (Figure S2). Both types exhibited firing properties characteristic of FS INs (Figures S2A, S2B, S2G, and S2H). However, the action potential (AP) half-width was significantly narrower for morphologically identified L6U IL-PV INs relative to L6L local PV INs (Figures S2F and S2L; L6U IL-PV INs: 0.37 ± 0.01 ms, n = 76; L6L local PV INs: 0.45 ± 0.03 ms, n = 33; p = 0.0017, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). PV INs in L6U that lacked identifiable axonal processes above L5b also had significantly narrower APs than local PVINsin L6L, indicating that narrower APs are a common feature of L6U PV INs (AP half-width: L6U local PV INs: 0.38 ± 0.03 ms, n = 17; L6L local PV INs: 0.45 ± 0.03 ms, n = 33; p = 0.0241, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These results show that there are two major types of PV INs in L6a with different morphologies and electrophysiological properties, each distributed within a sublayer of L6a.

Prior studies of the rodent somatosensory cortex have shown that L6 CThNs represent two distinct PN classes (Bourassa et al., 1995; Chevée et al., 2018; Killackey and Sherman, 2003; Zhang and Deschênes, 1997), although differences in the function of these two classes are poorly understood. One projects to the ventral posterior medial nucleus (VPM) of the thalamus (VPM-only L6 CThNs), while the other projects to both the VPM and the posterior medial nucleus (POm) (VPM/POm L6 CThNs). The somas of VPM-only L6 CThNs are biased toward the top of L6a, while those of VPM/POm L6 CThNs are biased toward the bottom (Figures 1K and 1L). Comparing the distributions of the somas of IL-PV and local PV INs with those of these two L6 CThN cell types, we found that VPM-only CThNs are in the same L6a sublamina as L6U IL-PV INs, while VPM/POm CThNs are found in L6L, where local PV INs predominate (Figure 1M). These results highlight that L6U and L6L have morphologically distinct inhibitory and excitatory cell types.

Interlaminar Parvalbumin Interneurons (IL-PV INs) Are Strongly Driven by Thalamocortical Input

Previous studies have shown that TC afferents from VPM, which carry sensory information detected by whisker deflections, are a major input to the infragranular barrel cortex (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Constantinople and Bruno, 2013; de Kock et al., 2007; Kinnischtzke et al., 2016; Kinnischtzke et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2010; Oberlaender et al., 2012; Viaene et al., 2011). Since eliminating this thalamic input sharply reduces the responses of neurons in the infragranular layers (Constantinople and Bruno, 2013), we asked how this input acted on L6a neurons (Figures 2, S3, and S4). Since TC axons from VPM ramify at the L5-L6 border (Oberlaender et al., 2012; Wimmer et al., 2010), we first tested whether these axons provide stronger input to neurons in L6U relative to L6L. We expressed channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in TC axons by stereotaxically injecting a virus carrying a ChR2-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) construct into VPM to transduce TC neurons. We then recorded postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) evoked by optogenetic activation of VPM TC inputs in pairs of L6U and L6L CThNs (Figure S3). We found that the amplitudes of the short-latency PSPs in L6U CThNs were significantly larger than in L6L CThNs (Figure S3C; p = 0.0078, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). These functional results are consistent with anatomical studies demonstrating that VPM TC axons are biased to L6U.

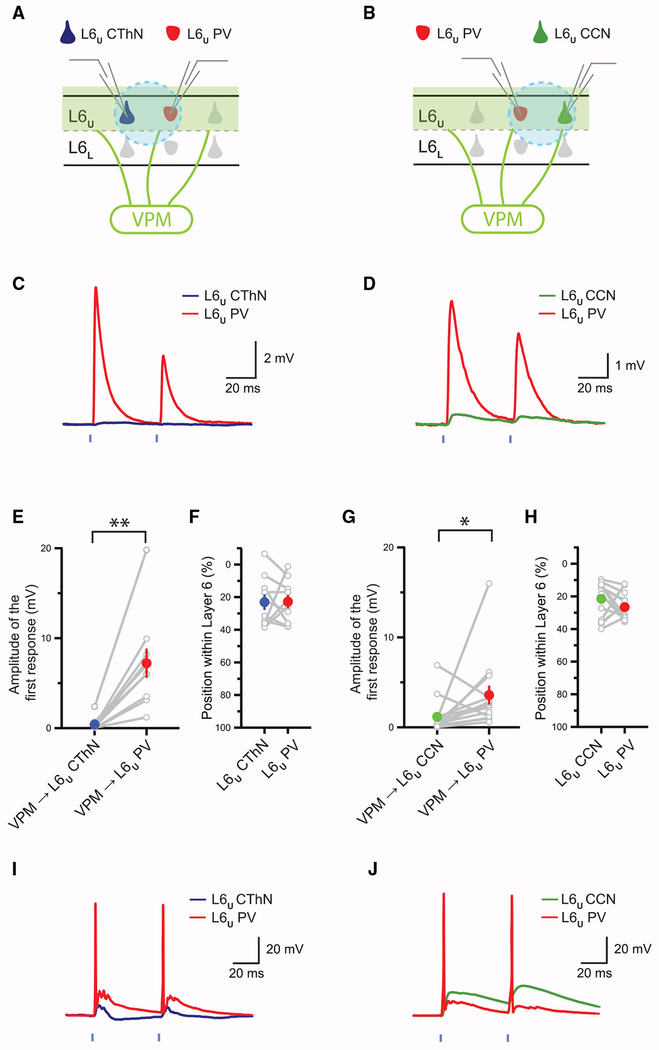

Figure 2. Thalamocortical (TC) Input Is Stronger onto IL-PV INs Than CThNs or CCNs in L6U.

(A and B) Recording configurations for L6U CThN-L6U PV IN (A) and L6U CCN-L6U PV IN (B) pairs.

(C and D) Examples of monosynaptic TC input to an L6U CThN and L6U PV IN (C) and to an L6U CCN and L6U PV IN (D) pair.

(E and G) Summary data of the amplitudes of monosynaptic TC input to L6U CThN and L6U PV IN pairs (E; n = 10; p = 0.0020, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and to L6U CCN and L6U PV IN pairs (G; n = 14; p = 0.0419, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

(F and H) Summary data of the laminar positions in L6a for each L6U PV-L6U CThN (F) and L6U PV-L6U CCN pair (H) recorded in (E) and (G).

(I and J) Responses recorded in an L6U PV and L6U CThN (I) and an L6U PV and L6U CCN pair (J) under conditions that evoked action potentials in at least one neuron.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

Next, we compared the impact of this TC input across CThNs, CCNs, and PV INs in L6U. We recorded PSPs evoked by the optogenetic activation of VPM TC input from pairs composed of an L6U PV and an L6U CThN. The amplitudes of the TC PSPs were significantly larger in L6U PV INs than in L6U CThNs (Figure S4; p = 0.0098, Wilcoxon signed-rank test), which is consistent with prior studies in which the type of FS IN was not determined (Beierlein et al., 2003; Cruikshank et al., 2007; Kinnischtzke et al., 2014). However, optogenetic activation of VPM inputs evoked early excitation followed by strong inhibition in some neurons, making it challenging to directly compare the monosynaptic excitatory TC input across cells.

To isolate the monosynaptic excitatory VPM input to cells in L6U, we optogenetically stimulated TC axons in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) (Petreanu et al., 2007) and recorded optogenetically evoked monosynaptic postsynaptic responses in L6 neurons. We recorded from pairs composed of an L6U PV IN and an L6U CThN (Figure 2A) and found that L6U PV INs exhibited significantly larger monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) than did L6U CThNs (Figures 2C, 2E, and 2F). We next recorded from pairs composed of an L6U PV IN and a CCN in L6U (Figure 2B) and similarly found that L6U PV INs exhibited significantly larger monosynaptic EPSPs than L6U CCNs (Figures 2D, 2G, and 2H). These data show that L6U PV INs receive stronger VPM TC input than either L6U CThNs or CCNs.

Although the amplitudes of the monosynaptic EPSPs measured in L6U PV INs were significantly larger than in either L6U CThNs or CCNs, these differences may not translate into differences in the spiking behavior evoked by TC input among the cell types. ChR2-evoked neurotransmitter release in the presence of TTX and 4-AP may be distorted relative to release under more physiological conditions. Furthermore, strong polysynaptic inhibition may affect L6U PV INs more than L6U CThNs and CCNs, reducing the effect of the differences in monosynaptic TC responses among cell types. We found that in the absence of TTX and 4-AP, the optogenetic activation of TC axons often evoked APs in L6U PV INs while generating subthreshold PSPs in L6U CThNs and CCNs recorded simultaneously (Figures 2I and 2J). For the nine L6U CThN-L6U PV pairs tested in which at least one cell fired APs, the L6U PV IN alone fired APs in seven pairs. In one pair, both fired APs. In only one case did the L6U CThN alone fire APs. Similarly, in a separate set of experiments, for seven out of eight tested L6U CCN-L6U PV pairs in which at least one cell fired APs, TC input evoked APs only in the L6U PV IN. In the remaining pair, both fired APs. Thus, the spiking behavior of the postsynaptic neurons in L6U in normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) was consistent with the differences in monosynaptic VPM input that we identified. Our data indicate that VPM input more strongly activates neurons in L6U relative to L6L and that this TC input drives L6U PV INs more than either major class of excitatory PN in L6U, CThNs or CCNs.

Parvalbumin Interneurons in L6U Do Not Preferentially Receive Synapses from CThNs

Prior studies of the local synaptic organization of L6 indicate that INH INs preferentially receive input from L6 CThNs relative to L6 CCNs (Thomson, 2010; West et al., 2006). Furthermore, optogenetic activation of L6 CThNs enhances the activity of IL-PV and local PV INs (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018). We tested whether L6U PV INs exhibit a privileged relation with L6 CThNs by comparing the synaptic connections of L6 CThNs and L6 CCNs onto PV INs using paired whole-cell recordings. We identified both L6U CThN→L6U PV and L6U CCN→L6U PV unitary connections (Figures 3A–3D). The probability of synaptic connection was similar for both types (Figure 3E; Table 1). The results were similar when restricted to pairs including morphologically recovered IL-PV INs (L6U CThN→L6U IL-PV: 43%, n = 16 of 37 tested connections; L6U CCN→L6U IL-PV: 45%, n = 15 of 33 tested connections; p = 1, Fisher’s exact test). The amplitudes of the unitary EPSPs for L6U CCN→L6U PV and L6U CThN→L6U PV connections were not significantly different, although L6U CCN→L6U PV EPSPs tended to be larger (Figure 3F; Table 1). When the analysis was restricted to morphologically recovered IL-PV INs, L6U CCN→L6U IL-PV connections were significantly stronger than L6U CThN→L6U IL-PV connections (L6U CCN→L6U IL-PV: 1.06 ± 0.29 mV, n = 15; L6U CThN→L6U IL-PV: 0.43 ± 0.13 mV, n = 16; p = 0.0459, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). These results indicate that CThNs do not form unitary connections onto L6U PV INs with a greater probability or strength of connection than CCNs. Rather, L6U IL-PV INs are positioned to integrate local excitatory input from both major classes of L6 PNs.

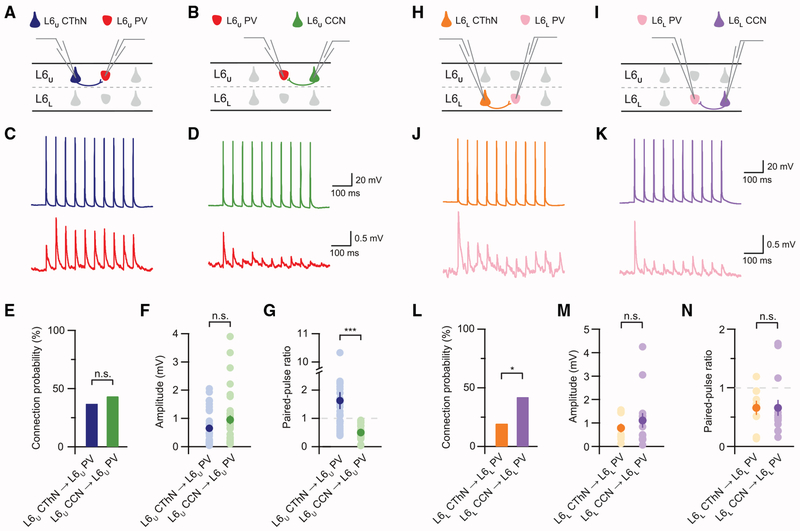

Figure 3. CThNs in L6a Do Not Preferentially Synapse onto Either IL-PV INs in L6U or Local PV INs in L6L.

(A and B) Recording configurations for L6U CThN-L6U PV IN (A) and L6U CCN-L6U PV IN (B) pairs.

(C and D) Unitary synaptic connections for an L6U CThN→L6U PV (C) and an L6U CCN→L6U PV (D) pair.

(E) The probability of connection for tested L6U CThN→L6U PV and L6U CCN→L6U PV connections (L6U CThN→L6U PV: 37%, n = 32 of 86 tested connections; L6U CCN→L6U PV: 44%, n = 34 of 78 tested connections; p = 0.43, Fisher’s exact test).

(F) The amplitudes of the unitary excitatory postsynaptic potentials (uEPSPs) of connected pairs (L6U CThN→L6U PV: 0.65 ± 0.12 mV, n = 32; L6U CCN→L6U PV: 0.95 ± 0.16 mV, n = 34; p = 0.1190, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

(G) The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) for connected pairs differed between the two types of connections (p = 9.3728 × 10−9, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

(H and I) Recording configurations for L6L CThN-L6L PV IN (A) and L6L CCN-L6L PV IN (B) pairs.

(J and K) Unitary synaptic connections for an L6L CThN→L6L PV (J) and an L6L CCN→L6L PV (K) pair.

(L) The probability of connection for tested L6L CThN→L6L PV and L6L CCN→L6L PV connections (L6L CCN→L6L PV: 42%, n = 14 of 33 tested connections; L6L CThN→L6L PV: 20%, n = 9 of 46 tested connections; p = 0.0436, Fisher’s exact test).

(M) The amplitudes of the uEPSPs of connected pairs (L6L CThN→L6L PV: 0.78 ± 0.19 mV, n = 9; L6L CCN→L6L PV: 1.11 ± 0.32 mV, n = 14; p = 0.9247, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

(N) The PPR for connected pairs (p = 0.5495, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

See also Figures S5 and S6.

Table 1.

Synaptic Connectivity, uEPSP and uIPSP Amplitudes, and Paired-Pulse Ratio

| Presynaptic | Postsynaptic | Connection Probability, % (Found/Tested) | uPSP Amplitude, mV, Mean ± SEM (n) | PPR, Mean ± SEM (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L6U | ||||

| L6U CThN | L6U PV | 37 (32/86) | 0.65 ± 0.12 (32) | 1.63 ± 0.30 (32) |

| L6U CCN | L6U PV | 44 (34/78) | 0.95 ± 0.16 (34) | 0.50 ± 0.04 (34) |

| L6U PV | L6U CThN | 54 (46/86) | −0.41 ± 0.05 (46) | 0.59 ± 0.03 (46) |

| L6U PV | L6U CCN | 40 (31/77) | −0.77 ± 0.15 (31) | 0.52 ± 0.03 (31) |

| L6L | ||||

| L6L CThN | L6L PV | 20 (9/46) | 0.78 ± 0.19 (9) | 0.66 ± 0.17 (9) |

| L6L CCN | L6L PV | 42 (14/33) | 1.11 ± 0.32 (14) | 0.66 ± 0.14 (14) |

| L6L PV | L6L CThN | 37 (17/46) | −0.62 ± 0.13 (17) | 0.60 ± 0.05 (17) |

| L6L PV | L6L CCN | 42 (14/33) | −0.56 ± 0.25 (14) | 0.61 ± 0.05 (14) |

| Across L6U and L6L | ||||

| L6L CThN | L6U PV | 0 (0/28) | – | – |

| L6U PV | L6L CThN | 7 (2/28) | −1.59, −3.35 | 0.66, 0.31 |

The probability of identifying a synaptic connection for each connection tested is shown along with the number of identified connections among the total connections tested for each type (found/tested). The mean amplitude ± SEM of the peak unitary postsynaptic potential (uPSP), excitatory or inhibitory as appropriate, is also shown, as is the mean paired-pulse ratio (PPR) ± SEM for each combination of presynaptic and postsynaptic cell types tested. In both cases, the number of connections analyzed (n) is shown in parentheses following these values. Please refer to Figures 3, 5, S5, and S6 for plots of the individual data points, except for L6U PV→L6L CThN connections; the values for both identified connections are shown here.

The strength of synaptic connections is dynamically regulated on millisecond timescales by the pattern of presynaptic APs. Most cortical excitatory connections depress, meaning the amplitude of the postsynaptic response becomes progressively smaller with each subsequent AP. However, some cortical synapses exhibit enhancement of each subsequent response. Facilitating synapses onto TC neurons (Crandall et al., 2015; Deschênes and Hu, 1990; Jackman et al., 2016; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Turner and Salt, 1998) and cortical neurons within (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; West et al., 2006) and outside L6 (Ferster and Lindström, 1985; Stratford et al., 1996) is considered a signature of L6 CThNs. In contrast, L6 CCN synapses depress (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Crandall et al., 2017; Mercer et al., 2005). Consistent with this work, we found that L6U CThN synapses onto L6U PV INs facilitate, while CCN synapses onto L6U PV INs depress (Figure 3G; Table 1). These data indicate that although L6U CThNs and CCNs synapse with similar frequency onto L6U PV INs, the influence of each input type depends on the precise patterns of presynaptic APs.

IL-PV INs Synapse Similarly onto CThNs and CCNs in L6U

Some recent studies suggest that INH INs synapse promiscuously onto PNs (Fino and Yuste, 2011; Packer and Yuste, 2011); others have shown that INH INs differentially innervate different classes of PNs (Hu et al., 2014; Krook-Magnuson et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2017; Morishima et al., 2017). We asked whether L6U PV INs distinguish between CThNs and CCNs when forming inhibitory connections. We identified both types of unitary connections (Figures S5A and S5B) and found no difference in the probability of connection (Figure S5C; Table 1; L6U PV→L6U CThN: 54%, n = 46 of 86 connections tested; L6U PV→L6U CCN: 40%, n = 31 of 77 connections tested, p = 0.1161, Fisher’s exact test; morphologically recovered L6U IL-PV→L6U CThN: 59%, n = 22 of 37 connections tested; morphologically recovered L6U IL-PV→L6U CCN: 45%, n = 15 of 33 connections tested; p = 0.3377, Fisher’s exact test), connection strength (Figure S5D; Table 1; p = 0.1120, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), or short-term synaptic plasticity (Figure S5E; Table 1; p = 0.1803, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). The probability of identifying reciprocal connections was also similar (Figure S5F; L6U PV-L6U CThN, 27%, n = 23 of 86 pairs tested; L6U PV-L6U CCN, 27%, n = 21 of 77 pairs tested; p = 1, Fisher’s exact test). Thus, L6U IL-PV INs form connections onto L6U CThNs and CCNs with high probability, and the properties of these synapses do not depend on the identity of the postsynaptic target.

CCNs in L6L Synapse More Frequently onto Parvalbumin Interneurons Than Do CThNs

In view of the striking morphological differences between L6U and L6L PV INs, we next asked whether the local synaptic organization of these two cell types differed. We identified both L6L CThN→L6L PV and L6L CCN→L6L PV unitary connections (Figures 3H–3K). Although the amplitudes of the unitary responses were similar for L6L CThN→L6L PV and L6L CCN→L6L PV connections (Figure 3M; Table 1), L6L CCNs were twice as likely to synapse onto an L6L PV IN than L6L CThNs (Figure 3L; Table 1). Next, we determined the short-term plasticity of the two types of inputs onto L6L PV INs. Although synaptic facilitation is considered a signature feature of L6 CThNs, we found that L6L CThNs, on average, form depressing synapses onto L6L PV INs, similar to the depressing synapses formed by L6L CCNs (Figure 3N; Table 1). These depressing L6L CThN→L6L PV synapses contrast with the facilitating L6U CThNs→L6U PV synapses. Our data indicate that the synaptic organization of PV INs in L6L differs from L6U and also significantly differs from prior proposals: L6L CThNs synapse onto L6L PV INs at half the rate of CCNs, and these L6L CThN→L6L PV synapses are depressing rather than facilitating.

As for L6U IL-PV INs, we found no difference in the probability of connection from L6L PV INs onto L6L CThNs or CCNs (Figures S6A–S6C; Table 1; L6L PV→L6L CThN: 37%, n = 17 of 46 connections tested; L6L PV→L6L CCN: 42%, n = 14 of 33 connections tested; p = 0.6475, Fisher’s exact test), the average synaptic strength (Figure S6D; Table 1; p = 0.0773, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), the paired-pulse ratio (Figure S6E; Table 1; p = 0.7964, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), or the probability of forming reciprocal connections (Figure S6F; L6L PV-L6L CThN: 13%, n = 6 of 46 pairs tested; L6L PV-L6L CCN: 21%, n = 7 of 33 pairs tested; p = 0.3699, Fisher’s exact test), indicating that local L6L PV INs, like IL-PV INs, do not distinguish between CThNs and CCNs when forming inhibitory synaptic connections.

L6a Parvalbumin Interneurons and the Columnar Organization of L6a

A defining feature of the barrel cortex is its columnar organization, signaled by the neuronal organization and TC input in L4 (Simons, 1978; Woolsey and Van der Loos, 1970). This columnar organization is also reflected in L6a infrabarrels, defined by the TC input to L6 and the clustered distribution of L6 CThNs within and L6 CCNs between the infrabarrels (Crandall et al., 2017; Killackey and Sherman, 2003). No correlation was found between the infrabarrels and the horizontal distribution of INH INs, including PV INs (Crandall et al., 2017). Here, we asked how the vertical location of these infrabarrels related to the sublayers defined by the distribution of IL-PV and local PV INs. To identify infrabarrels, we cut TC slices from mice in which VPM/POm L6 CThNs were retrogradely labeled with tracer injections into POm (Agmon and Connors, 1991; Crandall et al., 2017). We stained the sections with antibodies to vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGluT2) to identify the presynaptic terminals of the TC input to barrel cortex. The infrabarrels as defined by VGluT2 staining (Figures 4A–4D) were found in L6U, where the IL-PV INs and VPM-only L6 CThNs are located. The cell bodies of the retrogradely labeled VPM/POm L6 CThNs were found below the infrabarrels, in L6L, where local PV INs predominate (Figures 4A–4D; n = 4 mice). Although it remains possible that a columnar organization may be identified in L6L using different criteria, our results indicate that the infrabarrel organization is found in L6U.

Figure 4. The Vertical Distribution of Interlaminar and Local Parvalbumin Interneurons Correlates with the Distribution of Infrabarrels in L6a and the Two Classes of L6a CThNs.

(A–D) Low-magnification view of the distribution of presynaptic terminals of thalamocortical afferents from VPM stained with antibodies to vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGluT2) in the barrels and infrabarrels (A, shown with asterisk), the barrel hollows visible via DAPI-stained nuclei in L4 (B, shown with asterisk), and VPM/POm L6 CThNs in L6L as well as L5 POm-projecting CThNs retrogradely labeled with fluorescent microspheres (C, red, Lumafluor). In (D), (A) and (C) are overlaid, showing that the infrabarrels are located in L6U, above the VPM/POm L6 CThNs in L6L.

(E and G) Localized injections biased toward L6U (E) or L6L (G) of an adenoassociated virus carrying a Cre-dependent YFP construct.

(F and H) Confocal images of L6 CThNs primarily in L6U (F) or L6L (H).

Scale bars, 100 μm in (A)–(D), (F), and (H); 200 μm in (E) and (G).

To further compare the columnar organization of L6U and L6L, we determined the horizontal extent of the processes of small populations of VPM-only L6U and VPM/POm L6L CThNs. We made localized viral injections of a Cre-dependent YFP construct into either L6U or L6L of the barrel cortex in Ntsr1-Cre mice, which express Cre in both types of L6 CThNs (Chevée et al., 2018). These injections showed that VPM-only L6U CThNs send processes to L4 in a columnar manner (Figures 4E and 4F), while VPM/POm L6L CThNs ramify more widely in L5a (Figures 4G and 4H). We found that the ratio of the horizontal extent of the axonal processes of VPM-only L6 CThNs in L4 and their cell bodies in L6U was 1.15 ± 0.04 (n = 10 sections from 4 mice), while the ratio of the horizontal extent of the axonal processes of VPM/POm L6 CThNs in L5a and their cell bodies in L6L was 1.87 ± 0.07 (n = 15 sections from 3 mice), indicating that small populations of VPM/POm L6 CThNs extend their axons significantly more widely than VPM-only L6 CThNs (p < 0.0000369, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). The laminar and columnar distributions of the intracortical processes of these small populations of VPM-only or VPM/POm L6 CThNs were consistent with single-cell reconstructions in rats (Zhang and Deschênes, 1997). These data show that L6U contains IL-PV INs, infrabarrels, and narrow VPM-only L6 CThNs that send processes to L4, while L6L contains local PV INs and more widely ramifying VPM/POm L6 CThNs that primarily target L5a.

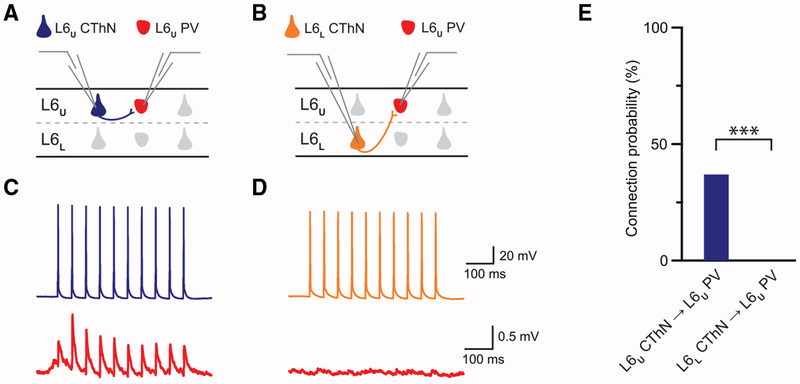

To further test whether these two sublayers, L6U and L6L, are functionally distinct, we determined whether L6L CThNs may activate L6U PV INs across sublayers by recording simultaneously from pairs composed of an L6L CThN and an L6U PV IN. We did not identify any L6L CThN→L6U PV connections (Figure 5; Table 1). We did, however, identify L6U PV→L6L CThN connections (Table 1; 7%, n = 2 of 28 tested connections), suggesting that the distance between the two recorded neurons is unlikely to be the sole explanation for the lack of L6L CThNs→L6U PV connections in our sample. Our data indicate that L6U PV INs receive excitatory input from VPM-only L6U CThNs and L6U CCNs in their home layer but not from VPM/POm L6L CThNs. Our data further show that L6U PV INs not only send interlaminar projections up toward the pia but they also synapse on PNs in L6L. Consistent with our morphological findings, these functional results suggest that L6U IL-PV INs inhibit neurons throughout the cortical column.

Figure 5. CThNs in L6L Do Not Synapse onto IL-PV INs in L6U.

(A and B) Recording configurations for L6U CThN→L6U PV IN (A) and L6L CThN-L6U PV IN (B) pairs.

(C) Unitary connection for an L6U CThN→L6U PV pair different from the pair in Figure 3C.

(D) Tested L6L CThN→L6U PV pair showing no synaptic connection.

(E) The probability of connection for tested L6U CThN/L6U PV (replotted from Figure 3E) and L6L CThN→L6U PV pairs (L6U CThN→L6U PV: 37%, n = 32 of 86 tested connections; L6L CThN→L6U PV: 0%, 0 of 28 tested connections; p = 2.2863 × 10−5, Fisher’s exact test).

DISCUSSION

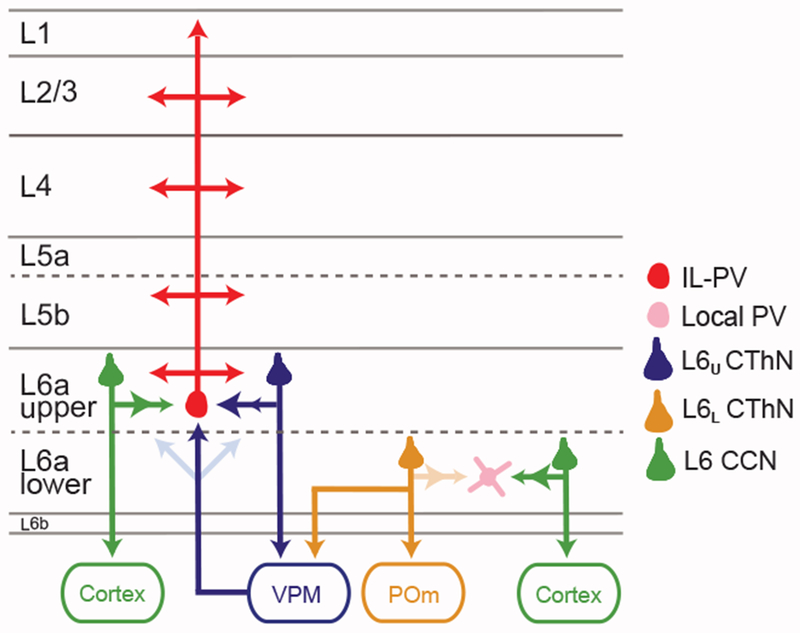

Our results provide strong evidence that the circuit organization of L6U and L6L is distinct, functionally subdividing the two sublayers (Figure 6). We found that IL-PV INs are restricted to L6U and integrate inputs from both the thalamus and local sources, supporting the hypothesis that they represent a final common interlaminar output for L6U. TC input more strongly activated L6U IL-PV INs than L6U CThNs and CCNs, which is consistent with previous studies that found that FS INs receive strong TC input (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Cruikshank et al., 2007; Kinnischtzke et al., 2014). A study showing that M1 input to S1 strongly activated FS INs at the L5-L6 border (Kinnischtzke et al., 2014) suggests that IL-PV neurons may integrate additional sources of long-range input. ynlike prior studies suggesting that L6 INH INs receive local input preferentially from L6 CThNs (Thomson, 2010; West et al., 2006), we found that L6U IL-PV INs receive input from both major PN types in L6U, VPM-only L6U CThNs, and CCNs. However, VPM-only L6U CThN→L6U IL-PV synapses facilitated while L6U CCN→L6U IL-PV synapses depressed, suggesting that L6U IL-PV INs will be influenced by the specific patterns of presynaptic activity as well as the distinct response profiles of L6U VPM-only CThNs and CCNs (Crandall et al., 2017; Vélez-Fort et al., 2014). L6 PNs are reported to have very low spike rates in the barrel cortex and other sensory cortices, which is consistent with their relatively weak TC input as compared to PV INs, although higher firing rates have been reported (Kwegyir-Afful and Simons, 2009; Landry and Dykes, 1985; Lee et al., 2008; Niell and Stryker, 2008; O’Connor et al., 2010; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Vélez-Fort et al., 2014). Under low-firing rate conditions, L6U CCN→IL-PV synapses would escape depression and may be favored, while L6U CThN input would remain unenhanced by facilitation. Higher firing rates may tip the balance toward VPM-only L6U CThN input onto IL-PV INs, as these synapses would facilitate, while L6U CCN synapses would depress. Prior studies suggest that the molecular and electrophysiological specializations of PV INs enhance their responses to convergent inputs within narrow temporal windows (Hu et al., 2014; Tremblay et al., 2016). Combined with our results and those of others (Crandall et al., 2017; Kinnischtzke et al., 2016; Vélez-Fort et al., 2014), the data suggest that L6U IL-PV INs are well positioned to integrate coincident input from the sensory periphery and internally generated input from other cortical areas. However, because the firing rates of L6U CThNs and CCNs under different conditions remain poorly understood, predicting how this circuitry will be engaged in the behaving animal remains challenging.

Figure 6. Summary Schematic Showing the Distinct Circuit Organization of L6U and L6L.

L6U IL-PV INs are restricted to L6U. The probability of connection onto L6U IL-PV INs is similar for VPM-only CThNs (VPM-only L6U CThNs) and CCNs in L6U, although the CThN synapses facilitate, while the CCN synapses depress (arrowheads). Thalamocortical input from VPM is stronger to L6U than to L6L and activates L6U IL-PV INs more than either VPM-only L6U CThNs or L6U CCNs. In L6L, CCNs have twice the probability of synapsing onto local PV INs than VPM/POm L6L CThNs. Both CCNs and CThNs form depressing synapses onto these local PV INs (arrowheads). Below L6a lies a molecularly distinct set of neurons called L6b.

As with L6U, the synaptic organization of L6L differed from the present models of L6 organization. First, rather than L6 CThNs preferentially synapsing onto INH INs (Thomson, 2010; West et al., 2006), VPM/POm L6L CThNs synapsed onto L6L PV INs at about half the frequency of L6L CCNs. Second, VPM→POm L6L CThN→L6L PV synapses depressed, an unexpected finding as facilitating synapses are considered a signature of L6 CThNs synapses (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Cotel et al., 2018; Crandall et al., 2015; Deschênes and Hu, 1990; Ferster and Lindström, 1985; Jackman et al., 2016; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Stratford et al., 1996; Turner and Salt, 1998; West et al., 2006). These results indicate that some key assumptions regarding the synaptic connectivity of L6 neurons do not hold in either L6U or L6L.

Since Cre recombinase is expressed in both VPM-only and VPM/POm L6 CThNs in Ntsr1-Cre mice (Chevée et al., 2018), using this line to modulate the activity of L6 CThNs in vitro and in vivo likely engages the circuits of both L6U and L6L, although perhaps to different degrees (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Williamson and Polley, 2019). Thus, disambiguating contributions from the two L6a sublayers to sensory processing using Ntsr1-Cre mice is challenging (Bortone et al., 2014; Crandall et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Williamson and Polley, 2019), although the circuit organization we show here suggests that the two sublayers have distinct functions. VPM-only L6U CThNs project to L4, the main thalamorecipient layer, and activate IL-PV INs, which also receive strong TC input, suggesting that L6U is involved in gain control and the modulation of cortical activity in response to sensory input (Guo et al., 2017; Mease et al., 2014; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018). VPM/POm L6L CThNs project to L5a, a cortical layer enriched in corticostriatal neurons and a major target of POm TC afferents, which unlike VPM inputs, undergo plasticity during sensory learning (Audette et al., 2019). This synaptic organization suggests that L6L may play a role in transmitting contextual information.

Whether the circuit organization we find in L6U represents a generalized implementation of a mechanism that broadly influences cortical activity to generate feedforward inhibition across the cortical layers, possibly regulating response gain or oscillations among neurons in the overlying cortical column, remains to be tested (Bortone et al., 2014; Crandall et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018; Williamson and Polley, 2019). IL-PV and local PV INs are found in the visual cortex of the rodent (Bortone et al., 2014), as are two classes of L6 CThNs, one in L6U that projects to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; LGN-only L6 CThNs) and another in L6L that projects to the LGN and lateral posterior (LP) nucleus (LGN/LP L6 CThNs) (Bourassa and Deschenes,1995). We would predict, therefore, parallels in the circuit organization of L6a neurons in the visual cortex and the barrel cortex. Interlaminar and local INs have been described in the infragranular layers of other mammals, but whether their cell bodies segregate into different L6 sublamina is not known (Kisvarday et al., 1987; Lund et al., 1988; Prieto and Winer, 1999). However, differences in the laminar distributions of L6 CThNs and CCN cell types across L6 have been described in other model organisms (Briggs et al., 2016; Conley and Raczkowski, 1990; Fitzpatrick et al., 1994; Hasse et al., 2019; Ichida et al., 2014; Lévesque et al., 1996; Prieto and Winer, 1999; Usrey and Fitzpatrick, 1996). In addition, in vivo recordings have noted distinct receptive field properties in L6U and L6L (Briggs and Usrey, 2009; Hirsch et al., 1998; Kwegyir-Afful and Simons, 2009; Landry and Dykes, 1985; Stoelzel et al., 2017; Swadlow and Weyand, 1987; Tsumoto and Suda, 1980). These data suggest that functional subdivisions of the classic L6 may be a more general feature of cortical organization.

The synaptic organization of inputs onto IL-PV INs, the low connectivity rate of L6 PNs onto other excitatory cortical neurons (Beierlein and Connors, 2002; Beierlein et al., 2003; Crandall et al., 2017; Lee and Sherman, 2009; Lefort et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2005; Schubert et al., 2003; Seeman et al., 2018; Tarczy-Hornoch et al., 1999; West et al., 2006), and the extensive inhibition evoked by activating L6 CThNs in vivo (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2012; Pauzin and Krieger, 2018) suggest that the main interlaminar output of L6U is columnar feedforward inhibition in response to the activity of local L6U CThNs and CCNs and long-range inputs to L6a. Our results indicate that an interlaminar inhibitory projection from a distinct sublamina in L6U contributes to the canonical cortical circuit.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Solange P. Brown (spbrown@jhmi.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

All procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the Society for Neuroscience. The following mouse lines were used: Neurotensin receptor-1 Cre recombinase line (Ntsr1-Cre, GENSAT 220, Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center 017266-UCD; (Gong et al., 2007)), loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato Cre reporter lines (Ai9 and Ai14, Allen Institute for Brain Science, Jackson 007905 and 007908; (Madisen et al., 2010)), a Gad1-GFP transgenic line (G42, Jackson 007677; (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2004)), a Parvalbumin-Cre recombinase line (PV-Cre, Jackson 008069, (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005)) and a mouse line carrying a Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin-2-YFP construct (Ai32, Allen Institute for Brain Science) (Madisen et al., 2012). All lines were maintained on a mixed background composed primarily of C57BL/6J and CD-1, and mice of either sex were used for experiments. All animals were maintained on a 12 hr light/dark cycle.

METHOD DETAILS

Injection of retrograde tracers and viral constructs

For injection of tracers and viruses, mice of either sex, postnatal day 20 (P20) to P60 were first anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg), dexmedetomidine (25 μg/kg) and the inhalation anesthetic, isoflurane. Animals were placed in a custom-built stereotaxic frame and anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (1%–2.5%). A small craniotomy was performed, a glass pipette loaded with tracer or virus was lowered into the brain, and the pipette was kept in position for up to 10 min before removal. Following the injection, the incision was sutured and the analgesic, buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg), was administered to all animals postoperatively.

To identify layer 6 corticothalamic neurons (L6 CThNs) projecting to the posterior medial nucleus (POm), Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice were injected with Alexa 488 Cholera toxin B (CTB488, ThermoFisher) or green Retrobeads IX (Lumafluor) using a 10–25 μm tip diameter pipette. Between 30 and 50 nL of tracer were pressure-injected into POm (1.35 mm posterior, 1.23 mm lateral, 3.3 mm ventral from bregma). Animals were sacrificed 5–10 days later to allow for retrograde transport of the tracer. To bias labeling to L6U CThNs or L6L CThNs and compare the distribution of neuronal processes, Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice were injected with AAV-DJ-EF1α-DIO-EYFP (Stanford Medicine Gene Vector and Virus Core) in barrel cortex using a pipette with a 10 μm tip diameter. Between 5 and 10 nL of virus were pressure-injected 850 μm below the surface of the brain to label L6U CThNs and 1500 μm below the surface to label L6L CThNs. Animals were sacrificed 1–2 weeks later to allow expression of the viral constructs. The horizontal extent of the labeled cell bodies in L6 and the axonal processes in layer 4 or 5a was measured in sections centered on the injection sites and the ratio was compared (L6U CThNs: 10 sections from 4 mice; L6L CThNs: 15 sections from 3 mice).

To compare the responses of CThNs, CCNs, and PV neurons to VPM input, AAV-DJ-CaMKIIα-ChR2-EYFP (Stanford Medicine Gene Vector and Virus Core) was injected into VPM (1.3 mm posterior, 1.8 mm lateral, 3.3 mm ventral from bregma) of Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato;Gad1-GFP mice (P24-P27). The mice were sacrificed 19-26 days after virus injection for electrophysiological recordings. In a subset of experiments, AAV-DJ-CaMKIIα-ChR2-EYFP and Alexa 488 Cholera toxin B were injected into the VPM of PV-Cre;tdTomato mice to identify CThNs and PV interneurons.

Brain slice preparation for electrophysiological recordings

Mice of either sex (P13-P47) were anesthetized using isoflurane, and their brains rapidly removed in an ice-cold sucrose solution containing the following (in mM): 76 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 75 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgSO4, pH 7.3, 315 mOsm. The brain was hemisected along the midline, and one or both hemispheres were mounted on a 30° ramp. Acute parasagittal slices of barrel cortex, 300 μm thick, were then sectioned in the same ice-cold sucrose cutting solution using a vibratome (VT-1200s, Leica). Slices were incubated in warm (32-35°C) sucrose solution for 30 min and then transferred to warm (32-35°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) composed of the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 20 D-(+)-glucose, 2 CaCl2, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 2 pyruvic acid, 4 L-lactic acid, pH 7.3, 315 mOsm. Slices were then allowed to cool to room temperature. All solutions were continuously equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Electrophysiology

Slices were transferred to a submersion chamber on an upright microscope (Zeiss AxioExaminer; 40x objective, 1.0 N.A.) and were continuously superfused (2-4 mL/min) with warm (~32-34°C), oxygenated aCSF. Neurons were visualized with a digital camera (Sensicam QE, Cooke) using either infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy or epifluorescence. The barrel cortex was identified based on the cytoarchitecture of the barrels in layer 4 (L4) viewed under IR-DIC, and slices in which the apical dendrites of infragranular pyramidal neurons ran parallel to the plane of the slice up through layer 2/3 (L2/3) in the area targeted for recording were selected.

PV-expressing interneurons were identified in two ways: first, by their expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a Gad1-GFP line in which GFP is selectively expressed in PV interneurons (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2004) or second, as tdTomato-expressing neurons in PV-Cre;tdTomato mice. L6 CThNs were targeted for recording based on tdTomato expression in Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato or Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato;Gad1-GFP mice (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014) or retrograde labeling from VPM. L6 CCNs were defined as unlabeled pyramidal neurons in Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice (Crandall et al., 2017) or mice in which L6 CThNs were retrogradely labeled from VPM. Although previous published work from our lab and others suggests good convergence between L6 CThNs identified by Cre expression in the Ntsr1-Cre mouse and by retrograde label (Bortone et al., 2014; Chevée et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014), it is possible that some label-negative L6 CThNs were misclassified as CCNs. Rare unlabeled cells with a fast-spiking phenotype or graded depolarizations to current injections were excluded from further analysis.

Patch pipettes (2-4 MΩ) pulled (Sutter P-97, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) from borosilicate capillary glass (Sutter Instruments) were filled with internal solution containing (in mM): 2.7 KCl, 120 KMeSO3, 9 HEPES, 0.18 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, 20 phosphocreatine(Na), pH 7.3,295 mOsm. For most recordings of PV interneurons, the internal solution included 0.25% w/v biocytin. In rare pairs, the biocytin-filled neuron had the morphology of a spiny pyramidal neuron with a prominent apical dendrite indicating biocytin was inadvertently included in the internal pipette solution for the pyramid and not the PV neuron; these cells were excluded from the anatomical analyses. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained using Multiclamp 700B amplifiers (Molecular Devices) and digitized using an Instrutech ITC-18 (Heka Instrument) and software written in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics). All signals were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at 20-100 kHz. Neurons with an access resistance greater than 30 MΩ or a resting membrane potential greater than −60 mV were eliminated from further analysis. The access resistance was not compensated in current clamp, and recordings were not corrected for the liquid junction potential.

Photostimulation for eliciting optogenetic responses

To compare the relative synaptic strength of VPM input to CThNs, CCNs, and PV interneurons, two brief pulses (1-3 ms) of a small spot (~200-250 μm diameter) of blue light (0.5-600 mW/mm2) were delivered as previously described using a blue LED (~470 nm; Luminous) (Kim et al., 2014) to photoactivate ChR2-expressing VPM axons. Except for Figures 2I and 2J, for each pair of cells recorded, the light intensity was adjusted so as not to evoke action potentials or depolarizations greater than ~30 mV by adjusting the LED intensity or placing a neutral density filter in the light path (ND10A, Thor Labs). Therefore, comparisons of the absolute magnitudes of the responses cannot be made across experiments. In Figures 2I and 2J, the light intensity was adjusted until action potentials were evoked in at least one of the two cells being recorded. When assessing monosynaptic inputs to L6 neurons, the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) and the potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 100 μM) were added to the aCSF (Petreanu et al., 2007). All recordings were performed with pairs of neurons to compensate for any differences in ChR2 expression across slices and regions within a slice.

Analysis of neuronal location and morphology

Following the recordings, high (40x, 1.0 or 0.8 N.A., Zeiss) and low (10× 0.3 N.A. or 5× 0.16 N.A. objectives, Zeiss) magnification images of the recorded cells were used to determine their laminar location in L6 of barrel cortex. Recorded neurons were located within L6a as L6b is located below the Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato-positive neurons (Figure S1). L6a was identified by drawing horizontal lines where the density of tdTomato-expressing CThNs in Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice largely decreased at the top and bottom of layer 6a, although a few tdTomato-positive neurons were found above and below these lines (Bortone et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014). Based on our anatomical data (Figures 1 and S1), we included neurons in upper L6a (L6U) located between −10% and 40% of the vertical extent of the tdTomato-expressing layer and neurons in lower L6a (L6L) between 60% and 110%. We excluded recordings from neurons located in the transition zone between 40% and 60% of the vertical extent of L6a.

At the end of the electrophysiological recording, the recording either simply ended or high amplitude, depolarizing current steps (set to 10 nA for 100 ms at ~1 Hz) were injected into the recorded neuron (Jiang et al., 2015). The procedures for recovering biocytin-filled neurons were modified from (Jiang et al., 2015) and (Marx et al., 2012). Briefly, slices were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at least overnight. Following fixation, slices were rinsed in 0.01 M PBS, and endogenous peroxidases were quenched in 1% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 10% methanol in 0.01 M PBS for 30 min. After at least six 10 min rinses in 0.01 M PBS, slices were then permeabilized in 3% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M PBS for 1 hr. Slices were then treated with an avidin-biotin complex solution (ABC, Vectastain) composed of 1% Reagent A with 1% of Reagent B in 2% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M PBS at least overnight at 4°C. Following at least six 10 min rinses in 0.01 M PBS, slices were incubated in 0.05% diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution with 0.033% H2O2 in 0.01 M PBS for approximately 5 min or until the slice turned light brown. Slices were then rinsed at least six times for 10 min in 0.01 M PBS and subsequently darkened via a one min incubation in 0.1% osmium in 0.01 M PBS. Slices were then rinsed at least six times for 10 min in 0.01 M PBS before being mounted onto glass slides and coverslipped in mowiol mounting media. All biocytin-filled PV interneurons with a cell body in L6 and visible axonal processes were included in the morphological analysis (n = 197 neurons) of the vertical extent of the axonal processes. Because neighboring filled cells had overlapping axons extending in the horizontal direction in a number of cases, we estimated the minimum horizontal extent for those L6U IL-PV interneurons (n = 108) and L6L local PV interneurons (n = 41) to the extent the axons could be clearly attributed to a particular cell. In cases when the horizontal extent was clear on only one side of the cell body, we estimated that the horizontal extent was symmetric around the cell body. Representative L6 PV interneurons were reconstructed in three dimensions using a Neurolucida system (Microbrightfield) on an Imager.M2 microscope (100× 1.4 N.A., oil immersion objective; Zeiss). No correction was made for tissue shrinkage.

Analysis of neuron distribution in layer 6

To assess the distribution of PV interneurons in L6, Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato;Gad1-GFP mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 4% PFA in 0.01 M PBS. Brains were removed and placed in 4% PFA in 0.01 M PBS overnight at 4°C, then washed three times for 10 min with PBS. Brains were mounted on a 30° ramp and parasagittal 30 μm sections were cut (VT-1000S, Leica). Sections were incubated for 1 h in 0.01 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum at room temperature, then incubated with rabbit anti-parvalbumin (PV25, 1:1000, Swant) at 4°C overnight. Following three 10 min rinses in PBS, slices were incubated with Alexa-647 donkey anti-rabbit (711-606-152, 1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 hr, then rinsed three times for 10 min with PBS, and then mounted on glass slides in Aqua-Poly/Mount (18606-20, Polysciences,) and visualized on a confocal microscope (LSM 800, Zeiss) using 10x (0.3 N.A.), 25x (0.8 N.A.) or 40x (1.3 N.A.) objectives. The vertical extent of L6 in the barrel cortex was defined by the distribution of tdTomato-positive cells. The vertical extent was then normalized, sublayers representing 10% of the vertical extent of L6 were delineated, and the number of PV-positive and GFP-positive neurons in each sublayer was counted for three sections from each of three hemispheres.

To assess the distribution of L6 CThN somas and their processes, brains from Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice injected with neuronal tracers in POm or viruses were processed in a similar manner. Coronal sections were cut on a vibratome (50 μm) and were subjected to immunohistochemistry (1:2000, rabbit anti-DsRed, Takara Bio Clontech, Cat. No. 632496, and 1:300 AlexaFluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit, Life Technologies, Cat. No. R37119). Mice injected with virus expressing YFP were subjected to additional immunohistochemistry (1:1000, chicken anti-GFP, Aves, Cat. No. GFP-1020, and 1:300 AlexaFluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-chicken, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat. No. 705-745-155) to amplify the signal. Sections were then mounted using Aqua-Poly/Mount and visualized on a confocal microscope. Colocalization of tdTomato and retrograde tracer was quantified using single-plane confocal images and the Cell Counter plugin in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012).

To distinguish L6b from L6a, brain slices were cut from Ntsr1-Cre;tdTomato mice (Figures S1A and S1B) or from mice in which a retrograde tracer (CTB) was injected into POm (Figure S1C) as described above. Brain slices were stained with an antibody to connective tissue growth factor (CTGF; goat anti-CTGF, 1:1000, Cat. No. SC-14939, Santa Cruz), which labels neurons in L6b (Heuer et al., 2003) and a fluorescent secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 488-conjugated Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H+L) antibody, 1:1000, Cat. No. A-11055, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sections were then mounted using Aqua-Poly/Mount and visualized on a confocal microscope.

To identify infrabarrels, VPM/POm L6 CThNs were labeled with a retrograde tracer (red Lumofluor beads) stereotaxically injected into POm in Ntsr1-Cre;ChR2-YFP mice as described above. Thalamocortical slices of the barrel cortex were then cut from these mice as previously described (Agmon and Connors, 1991; Crandall et al., 2017). Sections were processed as described above with the addition of an antibody retrieval step. Slices were immersed in L.A.B. Solution (Polysciences, Cat. No. 24310) for 5-10 min prior to further processing. The sections were then rinsed three times in 0.01 M PBS for at least ten min and were then incubated in 0.01 M PBS with 1% Triton X-100 and 10% normal donkey serum at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were then incubated with guinea pig anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGluT2) antibodies (1:10,000; Millipore, Cat. No. Ab2251-l) in 0.4% Triton X-100 and 2% normal donkey serum at 4°C overnight. Following three 10 min rinses in PBS, slices were incubated with Alexa-647 donkey anti-guinea pig (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat. No. 706-605-148) for 1 h, then rinsed three times for 10 min with PBS. The sections were then incubated in DAPI solution (1:50,000; ThermoFisher, Cat. No. D1306) in 0.01 M PBS for 5-10 min and then rinsed three times for 5 min in PBS. The slices were then mounted on glass slides in Aqua-Poly/Mount (18606-20, Polysciences) and visualized on an epifluorescence microscope (BZ-X 710, Keyence).

Analysis of neuronal properties and synaptic connectivity

The resting membrane potential (RMP) was measured shortly after establishing the whole-cell current-clamp recording configuration. A 1 s hyperpolarizing current pulse was used to calculate the input resistance of recorded neurons. To assess the spiking behavior of the cell, 1 s depolarizing current steps were injected into the recorded neurons. The properties of action potentials were analyzed using traces in which only a single action potential was elicited; neurons without such traces were not included in this analysis.

To determine the properties of unitary synaptic connections among neurons, ten action potentials were generated in the presynaptic neuron by injecting short, depolarizing current steps (3 ms pulse duration, 20 Hz, 10 s intertrial interval). Synaptic connectivity was assessed by averaging at least 25 consecutive traces of the postsynaptic response. Because some L6 CThN synapses facilitated, a synaptic connection was detected if the amplitude of the first or second response was greater than 2.5 times the root mean squared (RMS) of the average trace collected for 25 or more traces during baseline conditions. The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was calculated by dividing the amplitude of the second postsynaptic potential by the first. The average distance and standard deviations between recorded pairs were: L6U CThN→L6U PV, connected: 41 ± 18 μm, n = 30; unconnected: 43 ± 22 μm, n = 51; L6U PV→L6U CThN, connected: 40 ± 17 μm, n = 44; unconnected: 44 ± 23 μm, n = 37; L6U CCN→L6U PV, connected: 42 ± 18 μm, n = 33; unconnected: 47 ± 17 μm, n = 40; L6U PV→L6U CCN, connected: 43 ± 20 μm, n = 28; unconnected: 46 ± 16 μm, n = 44; L6L CThN→L6L PV, connected: 40 ± 17 μm, n = 9; unconnected: 36 ± 18 μm, n = 35; L6L PV→L6L CThN, connected: 39 ± 20 μm, n = 17; unconnected: 35 ± 15 μm, n = 27; L6L CCN→L6L PV, connected: 37 ± 13 μm, n = 14; unconnected: 40 ± 22 μm, n = 18; L6L PV→L6L CCN, connected: 41 ± 20 μm, n = 14; unconnected: 37 ± 18 μm, n = 18; L6L CThN→L6U PV, unconnected: 218 ± 64 μm, n = 24; L6U PV→L6L CThN, connected: 208 μm, n = 1; unconnected: 219 ± 65 μm, n = 23.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All analyses were performed in Igor Pro, MATLAB or Excel. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. All statistical tests were two-tailed. The Fisher exact test, Chi square test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used to test for statistical significance as noted in the text.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

The data and custom code used for analyses will be made available upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-parvalbumin | Swant | Cat. No.: PV25; RRID: AB_10000344 |

| Chicken anti-GFP | Aves | Cat. No.: GFP-1020; RRID: AB_10000240 |

| Rabbit anti-DsRed | Takara Bio Clontech | Cat. No.: 632496; RRID: AB_10013483 |

| Goat anti-Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) | Santa Cruz | Cat. No.: SC-14939; RRID: AB_638805 |

| Guinea pig anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGluT2) | Millipore | Cat. No.: Ab2251-I; RRID: AB_2665454 |

| AlexaFluor 647-conjugated Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) antibody | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat. No.: 711-606-152; RRID: AB_2340625 |

| AlexaFluor 488-conjugated Donkey anti-Chicken antibody IgY (IgG) (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat. No.: 703-545-155; RRID: AB_2340375 |

| AlexaFluor 594-conjugated Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat No.: R37119; RRID: AB_141637 |

| AlexaFluor 488-conjugated Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H+L) antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat No.: A-11055; RRID: AB_2534102 |

| AlexaFluor 647-conjugated Donkey anti-Guinea pig IgG (H+L) antibody | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat. No.: 706-605-148; RRID: AB_2340476 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV-DJ-CaMKIIα-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP | Stanford Medicine Gene Vector and Virus Core | N/A |

| AAV-DJ-EF1α-DIO-EYFP | Stanford Medicine Gene Vector and Virus Core | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Tetrodotoxin | Tocris | Cat. No.: 1069 |

| 4-Aminopyridine | Sigma | Cat. No.: A78403 |

| Biocytin | Sigma | Cat. No.: B4261 |

| Green Retrobeads IX | Lumafluor | N/A |

| Red Retrobeads | Lumafluor | N/A |

| Alexa 488 Cholera toxin B | ThermoFisher | Cat. No.: C34775 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat. No.: 15710 |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Fisher Chemical | Cat. No.: H325-500 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma | Cat. No.: T9284 |

| Vectastain ABC kit | Vector Laboratories | Cat. No.: PK-6100 |

| 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine | Sigma | Cat. No.: D8001 |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat. No.:19152 |

| L.A.B. Solution | Polysciences Inc. | Cat. No.: 24310 |

| Aqua-Poly/Mount | Polysciences Inc. | Cat. No.: 18606-20 |

| DAPI solution | ThermoFisher | Cat. No.: D1306 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Neurotensin receptor-1 Cre recombinase line (Ntsr1-Cre) (Gong et al., 2007). | N/A | GENSAT 220, Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center 017266-UCD |

| Mouse: loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato Cre reporter lines (Ai9 and Ai14, Allen Institute for Brain Science) (Madisen et al., 2010) | N/A | Jackson 007905 and 007908 |

| Mouse: Gad1-GFP transgenic line (G42) (Chattopadhyaya et al., 2004) | N/A | Jackson 007677 |

| Mouse: Parvalbumin-Cre recombinase line (PV-Cre) (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005). | N/A | Jackson 008069 |

| Mouse: loxP-STOP-loxP-ChR2-YFP Cre reporter lines (Ai32, Allen Institute for Brain Science) (Madisen et al., 2012) | N/A | Jackson 012569 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Igor Pro 6 | WaveMetrics | N/A |

| MATLAB | MathWorks | N/A |

| Excel | Microsoft | N/A |

| ImageJ | NIH | N/A |

Highlights.

Distinct circuits in upper and lower layer 6a distinguish two functional sublayers

Interlaminar inhibitory neurons reside in a specialized sublayer in upper layer 6a

Interlaminar interneurons integrate both local and thalamic inputs

Interlaminar inhibitory projections contribute to the canonical cortical microcircuit

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank K. Deisseroth and the Stanford Neuroscience Gene Vector and Virus Core, S. Hestrin for Igor Pro routines, and J.Y. Cohen for thoughtful input. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Neurological Diseases (RO1 NS085121 and P30NS050274) and the National Science Foundation (NSF; 1656592). C.J.M. was supported by an NSF Predoctoral Fellowship and an NIH Training Grant (5T32EY017203). J.K. was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea Fellowship (NRF-2011-357-E00005). M.C. was supported by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds Fellowship. A.A.B. was supported by a Johns Hopkins Provost’s Undergraduate Research Award. S.P.B. was supported by a Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship in the Neurosciences.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.048.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Adesnik H, and Naka A (2018). Cracking the function of layers in the sensory cortex. Neuron 100, 1028–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmon A, and Connors BW (1991). Thalamocortical responses of mouse somatosensory (barrel) cortex in vitro. Neuroscience 41, 365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzt M, Sakmann B, and Meyer HS (2018). Anatomical correlates of local, translaminar, and transcolumnar inhibition by layer 6 GABAergic interneurons in somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex 28, 2763–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audette NJ, Bernhard SM, Ray A, Stewart LT, and Barth AL (2019). Rapid plasticity of higher-order thalamocortical inputs during sensory learning. Neuron 103, 277–291.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos AM, Usrey WM, Adams RA, Mangun GR, Fries P, and Friston KJ (2012). Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron 76, 695–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, and Connors BW (2002). Short-term dynamics of thalamocortical and intracortical synapses onto layer 6 neurons in neocortex. J. Neurophysiol 88, 1924–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Gibson JR, and Connors BW (2003). Two dynamically distinct inhibitory networks in layer 4 of the neocortex. J. Neurophysiol 90, 2987–3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone DS, Olsen SR, and Scanziani M (2014). Translaminar inhibitory cells recruited by layer 6 corticothalamic neurons suppress visual cortex. Neuron 82, 474–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa J, and Deschênes M (1995). Corticothalamic projections from the primary visual cortex in rats: a single fiber study using biocytin as an anterograde tracer. Neuroscience 66, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa J, Pinault D, and Deschênes M (1995). Corticothalamic projections from the cortical barrel field to the somatosensory thalamus in rats: a single-fibre study using biocytin as an anterograde tracer. Eur. J. Neurosci 7, 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs F(2010). Organizing principles of cortical layer 6. Front. Neural Circuits 4 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs F, and Usrey WM (2009). Parallel processing in the corticogeniculate pathway of the macaque monkey. Neuron 62, 135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs F, Kiley CW, Callaway EM, and Usrey WM (2016). Morphological substrates for parallel streams of corticogeniculate feedback originating in both V1 and V2 of the macaque monkey. Neuron 90, 388–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B, Di Cristo G, Higashiyama H, Knott GW, Kuhlman SJ, Welker E, and Huang ZJ. (2004). Experience and activity-dependent maturation of perisomatic GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex during a postnatal critical period. J. Neurosci 24, 9598–9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevée M, Robertson JJ, Cannon GH, Brown SP, and Goff LA (2018). Variation in activity state, axonal projection, and position define the transcriptional identity of individual neocortical projection neurons. Cell Rep. 22, 441–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley M, and Raczkowski D (1990). Sublaminar organization within layer VI of the striate cortex in Galago. J. Comp. Neurol 302, 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinople CM, and Bruno RM (2013). Deep cortical layers are activated directly by thalamus. Science 340, 1591–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotel F, Fletcher LN, Kalita-de Croft S, Apergis-Schoute J, and Williams SR (2018). Cell class-dependent intracortical connectivity and output dynamics of layer 6 projection neurons of the rat primary visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex 28, 2340–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall SR, Cruikshank SJ, and Connors BW (2015). A corticothalamic switch: controlling the thalamus with dynamic synapses. Neuron 86, 768–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall SR, Patrick SL, Cruikshank SJ, and Connors BW (2017). Infrabarrels are layer 6 circuit modules in the barrel cortex that link long-range inputs and outputs. Cell Rep. 21, 3065–3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Lewis TJ, and Connors BW (2007). Synaptic basis for intense thalamocortical activation of feedforward inhibitory cells in neocortex. Nat. Neurosci 10, 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzker JL, and Callaway EM (2000). Laminar sources of synaptic input to cortical inhibitory interneurons and pyramidal neurons. Nat. Neurosci 3, 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kock CP, Bruno RM, Spors H, and Sakmann B (2007). Layer- and cell-type-specific suprathreshold stimulus representation in rat primary somatosensory cortex. J. Physiol 581, 139–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes M, and Hu B (1990). Electrophysiology and pharmacology of the corticothalamic input to lateral thalamic nuclei: an intracellular study in the cat. Eur. J. Neurosci 2, 140–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, and Martin KA (2004). Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 27, 419–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D (2012). Excitatory neuronal connectivity in the barrel cortex. Front. Neuroanat 6, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Qi G, Emmenegger V, and Staiger JF (2018). Inhibitory interneurons and their circuit motifs in the many layers of the barrel cortex. Neuroscience 368, 132–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster D, and Lindström S (1985). Augmenting responses evoked in area 17 of the cat by intracortical axon collaterals of cortico-geniculate cells. J. Physiol 367, 217–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, and Yuste R (2011). Dense inhibitory connectivity in neocortex. Neuron 69, 1188–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D, Usrey WM, Schofield BR, and Einstein G (1994). The sublaminar organization of corticogeniculate neurons in layer 6 of macaque striate cortex. Vis. Neurosci 11, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Doughty M, Harbaugh CR, Cummins A, Hatten ME, Heintz N, and Gerfen CR (2007). Targeting Cre recombinase to specific neuron populations with bacterial artificial chromosome constructs. J. Neurosci 27, 9817–9823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Clause AR, Barth-Maron A, and Polley DB (2017). A corticothalamic circuit for dynamic switching between feature detection and discrimination. Neuron 95, 180–194.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, and Mrsic-Flogel TD (2013). Cortical connectivity and sensory coding. Nature 503, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasse JM, Bragg EM, Murphy AJ, and Briggs F (2019). Morphological heterogeneity among corticogeniculate neurons in ferrets: quantification and comparison with a previous report in macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol 527, 546–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H, Christ S, Friedrichsen S, Brauer D, Winckler M, Bauer K, and Raivich G (2003). Connective tissue growth factor: a novel marker of layer VII neurons in the rat cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 119, 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenmeyer S, Vrieseling E, Sigrist M, Portmann T, Laengle C, Ladle DR, and Arber S (2005). A developmental switch in the response of DRG neurons to ETS transcription factor signaling. PLoS Biol. 3, e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JA, Gallagher CA, Alonso JM, and Martinez LM (1998). Ascending projections of simple and complex cells in layer 6 of the cat striate cortex. J. Neurosci 18, 8086–8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerder-Suabedissen A, Wang WZ, Lee S, Davies KE, Goffinet AM, Rakić S, Parnavelas J, Reim K, Nicolić M, Paulsen O, and Molnár Z (2009). Novel markers reveal subpopulations ofsubplate neurons in the murine cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 19, 1738–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Gan J, and Jonas P (2014). Interneurons. Fast-spiking, parvalbumin+ GABAergic interneurons: from cellular design to microcircuit function. Science 345, 1255263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida JM, Mavity-Hudson JA, and Casagrande VA (2014). Distinct patterns of corticogeniculate feedback to different layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus. Eye Brain 2014 (6, Suppl 1), 57–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman SL, Turecek J, Belinsky JE, and Regehr WG (2016). The calcium sensor synaptotagmin 7 is required for synaptic facilitation. Nature 529, 88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Shen S, Cadwell CR, Berens P, Sinz F, Ecker AS, Patel S, and Tolias AS (2015). Principles of connectivity among morphologically defined cell types in adult neocortex. Science 350, aac9462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfer C, Glickfeld LL, Atallah BV, and Scanziani M (2007). Supralinear increase of recurrent inhibition during sparse activity in the somatosensory cortex. Nat. Neurosci 10, 743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kätzel D, Zemelman BV, Buetfering C, Wölfel M, and Miesenböck G (2011). The columnar and laminar organization of inhibitory connections to neocortical excitatory cells. Nat. Neurosci 14, 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey HP, and Sherman SM (2003). Corticothalamic projections from the rat primary somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci 23, 7381–7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]