Abstract

Objectives

This study identifies sociodemographic predictors of prescription opioid use among older adults (age 65+) during the peak decade of U.S. opioid prescription, and tests whether pain level and Medicaid coverage mediate the association between low wealth and opioid use. Predictors of prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and of opinions of both drug classes, are also examined.

Method

Regressions of opioid and NSAID use on sociodemographic characteristics, pain level, and insurance type were conducted using Health and Retirement Study 2004 core and 2005 Prescription Drug Study data (n = 3,721). Mediation analyses were conducted, and user opinions of drug importance, quality, and side effects were assessed.

Results

Low wealth was a strong, consistent predictor of opioid use. Both pain level and Medicaid coverage significantly, but only partially, mediated this association. Net of wealth, there were no significant associations between education and use of, or opinions of, either class of drugs.

Discussion

Among older American adults, the poorest are disproportionately likely to have been exposed to prescription opioid analgesics. Wealth, rather than education, drove social class differences in mid-2000s opioid use. Opioid-related policies should take into account socioeconomic contributors to opioid use, and the needs and treatment histories of chronic pain patients.

Keywords: Health disparities, Health insurance, NSAIDs, Opinions of drugs, Socioeconomic status (SES)

Among older American adults, which sociodemographic groups have been most likely to use prescription opioids? This question is important for several reasons. First, prescription opioids, either directly or as a gateway to illicit drugs, are a leading cause of overdose and drug poisoning deaths (Chen, Hedegaard, & Warner, 2014; Rudd, Aleshire, Zibbell, & Gladden, 2016). Second, although less well-publicized, growing evidence links prescription opioids to other adverse long-term outcomes, including depression (Scherrer et al., 2016), reduced immune function (Wiese, Griffin, Stein, Mitchel, & Grijalva, 2016), increased pain, increased health care utilization (Morasco et al., 2017), and increased risk of death due to causes other than overdose (Ray, Chung, Murray, Hall, & Stein, 2016). Third, as opioid prescription rates have decreased since the 2011 declaration of an opioid epidemic (CDC Vitalsigns, 2011; Goodnough, 2017), many pain patients relying on opioid therapy have found it increasingly difficult to access their drugs of choice, and may struggle to manage their pain in a changing therapeutic landscape (Carr, 2016).

Recent research on opioids has focused on social patterns in misuse or overdose. Studies find, for example, that prescription opioid misuse is more likely among non-Hispanic whites, the unmarried, the less educated, and urban residents (Rigg & Monnat, 2015), and that risk of opioid overdose is elevated among Medicaid enrollees (e.g., Fernandes, Campana, Harwell, & Helgerson, 2015; Sharp & Melnik, 2015). However, it is unclear how closely social patterns in misuse or overdose match those for prescribed, therapeutic use. Similarly, findings from the many studies of emergency department (ED) prescribing may not be indicative of overall, national patterns of prescription drug use. For example, ED-based studies regularly find minorities to be less likely to receive opioids than whites (e.g., Joynt et al., 2013; Pletcher, Kertesz, Kohn, & Gonzales, 2008), while findings from national data sets do not consistently demonstrate such differences (Frenk, Porter, & Paulozzi, 2015a; Harrison, Lagisetty, Sites, Guo, & Davis, 2018; Smith et al., 2017).

Recent research using national data to identify predictors of prescription opioid use (not misuse) has found higher rates among women, low-income individuals, and those in mid-life or beyond (Frenk et al., 2015a; Frenk, Porter, & Paulozzi, 2015b). Little research has focused specifically on older adults, however, despite their relatively high rates of opioid use and of chronic pain (Grol-Prokopczyk, 2017). Some studies, without explanation, exclude adults aged 65 and older altogether (e.g., Fernandes et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2017). Many studies also lack information about pain. Women, the less educated, and the poor are consistently found to have higher chronic pain prevalence and severity, while racial/ethnic minorities are often found to have lower prevalence (Grol-Prokopczyk, 2017). At present, it is unclear to what extent group differences in pain explain differences in opioid use.

Little research on predictors of prescription opioid use (again, as opposed to misuse or overdose) has used data with multiple, high-quality measures of socioeconomic status (SES), despite evidence that different facets of SES may vary in their importance for health in different contexts. In particular, while education often has a strong association with health behaviors, this association depends on the availability of relevant information, as noted in explications of fundamental cause theory (Montez & Friedman, 2015; Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010). For example, in the 1950s, when information about the risks of smoking was just emerging, no strong educational gradients in smoking-related beliefs or behavior were observed; these appeared only in subsequent decades, as the information spread and gained credibility (Link, 2008).

Were lay and/or medical beliefs about opioids in the 2000s (and earlier) comparable to 1950s-era beliefs about smoking, that is, reflecting a lack of knowledge about risks? The answer is unclear. On the one hand, by the early 2000s, national news stories periodically described the “growing wave of drug abuse” attributable to OxyContin (Clines & Meier, 2001), and the aggressive, deceptive marketing practices of its producer, Purdue Pharma (e.g., B. Meier & Petersen, 2001). On the other hand, concerns about opioids were also often dismissed during this period: readers critiqued journalists’ “excess focus on risks” as “distract[ing] from the primary importance” of effective pain treatment (e.g., D. E. Meier, 2001), and some widely cited medical studies argued against a link between opioid prescriptions and opioid abuse (e.g., Joranson, Ryan, Gilson, & Dahl, 2000).

Regardless of how well-understood the risks of opioids were, it is not a priori clear how prescription opioid use would be associated with social class. If physician decision making were key, and if doctors preferred to give opioids to groups deemed to have low risk of abuse or diversion, then opioids might be prescribed more frequently to high SES groups. If, however, patient decision making (or institutional context) were key, and higher SES individuals had greater desire and/or resources to pursue nonopioid treatments, then prescription opioids might be used more frequently by lower SES groups—those with fewer other options. In the first case, opioids would be disproportionately prescribed to the socially privileged; in the second, opioids would go disproportionately to the socially disadvantaged.

This article has three key goals. The first is to use national 2005–2006 data to provide a fuller understanding of sociodemographic predictors of prescription opioid use among older American adults, both to assess whether patterns in this group resemble those found in previous studies, and to clarify the independent roles of different facets of SES (in particular, education, wealth, and/or income. How was each associated with prescription opioid use, if at all?). To test whether findings were specific to opioids or apply to other drug classes, parallel analyses identify predictors of prescription NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) use. (Opioids, such as oxycodone, and NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, are the most common classes of drugs for pain treatment; Bajwa, Wootton, & Warfield, 2017.)

This study’s second key goal, emerging from the finding that low wealth was strongly predictive of opioid use, is to clarify mechanisms behind this association, focusing on pain and Medicaid enrollment as potential mediators. Although it is known that pain prevalence and severity are inversely associated with wealth (Grol-Prokopczyk, 2017), it is unclear whether this suffices to explain the link between low wealth and opioid use. This study formally tests this. Regarding Medicaid, studies from many U.S. states report elevated rates of opioid overdose among Medicaid enrollees (Fernandes et al., 2015). This may reflect characteristics of Medicaid patients (e.g., higher-than-average rates of substance abuse and mental health disorders) and/or their providers’ treatment practices, including higher opioid prescription rates and dosages (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Whether Medicaid enrollment predicts higher prescription opioid use specifically among older adults (despite their eligibility for Medicare, which also covers opioids), and how much this might explain the association between low wealth and opioid use, in unknown. This study thus also analyzes Medicaid as a potential mediator.

This study’s third goal is to use unique questions in the current data set to present and explore predictors of opinions of prescription analgesics. How did opioid and NSAID users feel about their drugs’ importance, quality, and side effects, and did such beliefs differ by social class? Because opinion questions were asked only of current drug users, they cannot be formally tested as mediators of drug use, but they may indirectly shed light on whether educational or other differences in beliefs played a role in shaping social patterns in prescription analgesic use.

This study uses data collected in 2005–2006—a specific, but historically important moment, falling in the peak period of U.S. opioid use as measured by prescription rate (Frenk et al., 2015a). These data pertain to prescription drug use, not misuse, but as noted, there are good reasons to identify the groups most likely to have recently been taking prescription opioids: they are the groups most likely to be currently contending with the risks of continued opioid use, and/or with the challenges of pain management in an increasingly opiophobic environment. Understanding how factors such as education, wealth, and health insurance type have shaped prescription analgesic use can shed light on how policies can best encourage safe and effective pain management practices going forward.

Method

Data

This research uses data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and conducted by the University of Michigan. The HRS began in 1992, in 1998 became representative of non-institutionalized Americans above age 50, and is periodically refreshed (including in 2004) to remain representative of that group. Respondents, including those becoming institutionalized, are followed longitudinally in biennial interviews conducted by telephone or in-person (Health and Retirement Study, 2008b). Detailed information about SES and health is collected in each biennial wave.

In October 2005, the HRS sent a supplemental mail survey, the 2005 Prescription Drug Study (PDS), to 5,314 still-living Medicare- and/or Medicaid-eligible respondents from the 2004 biennial survey. Fielding continued until March 2006, and included telephone follow-up for initial nonrespondents. Of those contacted, 4,376 (82.35%) returned a list of up to 10 prescription drugs they were currently taking, providing drug names, duration of use, and opinions of the drugs’ importance, quality, side effects, and cost (Health and Retirement Study, 2008a). Because people qualifying for Medicare before age 65 have long-term disability and/or specific serious medical conditions, and are thus not representative of the Medicare population as a whole, respondents under 65 were excluded from this study (n = 618). Respondents were also excluded for having a sample weight of zero (n = 19) or missing pain information (n = 18), yielding a final sample of 3,721 respondents (missing no key variables). Table 1 presents sample characteristics. Based on HRS survey weights, the sample is representative of 38,015,388 older Americans.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Analytic Sample (N = 3,721; from 2004 Health and Retirement Study and 2005 Prescription Drug Study)

| Proportion or mean, sample weight-adjusted | Proportion or mean, unadjusted | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, 2005 | |||

| 65–69 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 1,064 |

| 70–74 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 922 |

| 75–79 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 675 |

| 80+ | 0.29 | 0.28 | 1,060 |

| Female | 0.57 | 0.59 | 2,181 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 0.85 | 0.76 | 2,827 |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 0.07 | 0.13 | 470 |

| Hispanic | 0.06 | 0.09 | 351 |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 73 |

| Married, 2004 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 2,126 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 0.25 | 0.29 | 1,095 |

| High school diploma | 0.56 | 0.54 | 2,017 |

| 4-year college degree | 0.19 | 0.16 | 609 |

| Wealth, 2004 | |||

| Quartile 1 | $19,474 | $18,717 | 1,147a |

| Quartile 2 | $130,130 | $128,179 | 960a |

| Quartile 3 | $347,483 | $344,649 | 845a |

| Quartile 4 | $1,537,349 | $1,297,374 | 769a |

| Pain level, 2004 | |||

| No pain | 0.69 | 0.67 | 2,511 |

| Mild pain | 0.08 | 0.08 | 316 |

| Moderate pain | 0.18 | 0.18 | 662 |

| Severe pain | 0.06 | 0.06 | 232 |

| Health insurance type, 2004 | |||

| Medicare only | 0.27 | 0.30 | 1,098 |

| Medicare plus private insurance | 0.64 | 0.59 | 2,194 |

| Medicare plus Medicaid | 0.09 | 0.12 | 429 |

| Prescription drug use, 2005 | |||

| Prescription opioid user | 0.08 | 0.08 | 298 |

| Prescription NSAID user | 0.12 | 0.12 | 438 |

aWealth quartiles were generated with sample-weight adjustment. Thus, while the raw (unadjusted) counts of participants are not equal across quartiles, one-quarter of respondents fall in each quartile after sample-weight adjustment.

Dependent Variables

The key outcome variable was current use of a prescription opioid analgesic. Drugs were identified as opioids by comparing their generic names (provided by the PDS) with a comprehensive list of opioids generated from contemporaneous and current editions of pain medicine textbooks (Bajwa et al., 2017; Warfield & Bajwa, 2004) and the Drugs.com website. A similar procedure was used to identify NSAIDS (including COX-2 inhibitors). Eighteen percent of respondents (n = 678) were currently taking prescription opioids and/or NSAIDs: 240 took opioids only, 380 took NSAIDs only, and 58 took both.

Respondents’ opinions of their prescription analgesics were evaluated with a 5-point Likert scale indicating level of agreement with four statements: “This medication is very important for my health,” “It is the best one available for what it does,” “It often gives me unpleasant side effects,” and “It is too expensive.” Those who answered “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” were combined, and predictors of agreement assessed.

Independent and Control Variables

Key independent variables in this study were education (categorized as in Table 1), wealth quartiles, and, in alternate models, income quartiles. Wealth (total wealth including secondary residence) and income (total household income from respondent and spouse) came from RAND Income and Wealth Imputations, Version P (Pantoja et al., 2016). Wealth and income quartiles were created with sample-weight adjustment, to correspond to quartiles in the population. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status were controlled for in all multivariable models. Time-varying variables were measured in 2004.

Potential Mediators

Pain level and health insurance type were evaluated as potential mediators of the observed association between low wealth and opioid use. Pain level was based on responses to two questions: “Are you often troubled with pain?” and “How bad is the pain most of the time: mild, moderate or severe?” combined to create four dummy variables: no, mild, moderate, and severe pain. All respondents in this sample were eligible for Medicare. Those also covered by private plans were coded as “Medicare plus private insurance,” while those covered by Medicaid at any point in the last 2 years were coded as “Medicare plus Medicaid.”

Analyses

To assess both bivariate and multivariable associations of prescription opioid use with predictor variables, a series of logistic regressions were run: first bivariate regressions of opioid use on each individual variable; then a multivariable regression including all independent and control variables (Model 1); and finally a saturated model also including the potential mediators, pain and insurance type (Model 2—but see description of KHB analyses just below). For comparison, the same models were estimated with prescription NSAID use as the outcome (Models 3 and 4). Logistic regressions also tested whether sociodemographic characteristics predicted agreement with drug-related opinion statement, for both drug classes.

Because odds ratios (ORs) in nested logistic models cannot be directly compared or used to assess mediation (Mood, 2010), formal mediation analyses were conducted using the Karlson, Holm, and Breen (KHB) method. KHB was designed specifically to overcome the rescaling bias that complicates comparison of nested nonlinear probability models, and can decompose the total effect of a variable into direct and indirect (i.e., mediated) components (Kohler, Karlson, & Holm, 2011). Here, KHB was used to evaluate pain level and Medicaid coverage as mediators of the association between low wealth and opioid use. Bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effects were calculated (as recommended in Friedman, Karlamangla, Gruenewald, Koretz, & Seeman, 2015), using 2,000 replications.

To be indicative of population distributions, graphs of use and opinions of prescription analgesics were generated using survey weights (accounting for the HRS’s complex survey design). Given ongoing debate regarding whether to use sampling weights in multivariable models (Young & Johnson, 2012), regressions were run both with and without weights. Because weighted models are generally less efficient and hence provide more conservative estimates of group differences (Young & Johnson, 2012), weighted models are presented herein. Unweighted models are presented in Supplementary Appendix A. The KHB method does not permit sample-weight adjustment, but since weighted and unweighted logistic models in this study yielded very similar findings, the KHB results are likely broadly accurate reflections of associations in either context.

Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of findings to alternate specifications, as described in the Results section. Formal tests of collinearity, including assessment of variance inflation factors, confirmed that there were no problems of multicollinearity in any primary or alternate models. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15.1; code is available upon request.

Results

As indicated in Table 1, based on sample-weight adjusted estimates, 8.0% of adults 65+ were taking prescription opioids and 11.7% were taking prescription NSAIDs at the time of the survey. These estimates resemble those from other datasets with similar questions, for example, the 2007–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicates that 7.9% of Americans aged 60+ used prescription opioids in the last 30 days (Frenk et al., 2015a).

Predictors of Prescription Opioid Use

Results of sample-weight adjusted regressions examining predictors of prescription opioid use are presented in Table 2, left half. In bivariate analyses, being unmarried, having higher levels of pain, or having Medicaid coverage predicted significantly higher odds of opioid use, while being above the first wealth quartile predicted lower odds. Women had higher odds of opioid use than men, but this differences was not significant at the .05 level. Education did not significantly predict prescription opioid use, although in bivariate analyses not adjusting for sampling weights, there was a significant, negative association between education and opioid use. (All other findings from sampling-weight–adjusted and unadjusted models, both bivariate and multivariate, were very similar; Supplementary Appendix A.)

Table 2.

Sample-Weight Adjusted Logistic Regressions of 2005 Prescription Opioid/NSAID Use on Sociodemographic Characteristics, Pain Level, and Insurance Type (N = 3,721)

| Outcome: Rx opioid use | Outcome: Rx NSAID use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Model 1 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Model 2 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Bivariate Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Model 3 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Model 4 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Sex (ref.: male) | ||||||

| Female | 1.30† (0.97–1.75) |

1.12 (0.80–1.56) |

0.91 (0.65–1.28) |

1.13 (0.94–1.37) |

1.18† (0.97–1.43) |

1.11 (0.91–1.34) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref.: white) | ||||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 0.77 (0.54–1.10) |

0.57**

(0.39–0.85) |

0.64† (0.40–1.02) |

0.94 (0.59–1.51) |

0.89 (0.53–1.49) |

0.92 (0.55–1.52) |

| Hispanic | 1.15 (0.73–1.82) |

0.93 (0.59–1.45) |

0.90 (0.57–1.41) |

1.51**

(1.13–2.01) |

1.44*

(1.04–1.99) |

1.32 (0.94–1.95) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 0.67 (0.30–1.46) |

0.60 (0.28–1.28) |

0.59 (0.29–1.22) |

1.87*

(1.06–3.29) |

1.73† (0.95–3.15) |

1.65† (0.91–3.01) |

| Marital status (ref.: married) | ||||||

| Not married |

1.54**

(1.14–2.07) |

1.18 (0.81–1.72) |

1.25 (0.86–1.82) |

0.92 (0.69–1.21) |

0.95 (0.71–1.27) |

0.94 (0.70–1.27) |

| Education (ref.: no degree) | ||||||

| High school diploma | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) |

1.02 (0.69–1.50) |

1.10 (0.74–1.64) |

0.92 (0.68–1.24) |

0.95 (0.68–1.33) |

1.01 (0.72–1.42) |

| 4-year college degree | 0.66 (0.36–1.19) |

0.94 (0.50–1.77) |

1.17 (0.62–2.23) |

1.09 (0.76–1.57) |

1.03 (0.68–1.57) |

1.19 (0.76–1.85) |

| Wealth, 2004 (ref.: Q1) | ||||||

| Quartile 2 |

0.58**

(0.41–0.82) |

0.56**

(0.40–0.80) |

0.66*

(0.46–0.94) |

0.75† (0.54–1.04) |

0.77 (0.54–1.09) |

0.91 (0.63–1.31) |

| Quartile 3 |

0.57**

(0.38–0.86) |

0.56*

(0.36–0.88) |

0.67 (0.41–1.09) |

0.74† (0.52–1.04) |

0.76 (0.52–1.10) |

0.92 (0.60–1.39) |

| Quartile 4 (wealthiest) |

0.47**

(0.29–0.77) |

0.49**

(0.28–0.83) |

0.64 (0.35–1.19) |

1.07 (0.81–1.41) |

1.08 (0.76–1.52) |

1.38† (0.94–2.02) |

| Pain, 2004 (ref.: no pain) | ||||||

| Mild pain |

2.55***

(1.62–4.02) |

2.58***

(1.60–4.14) |

1.37 (0.94–2.00) |

1.37 (0.94–2.01) |

||

| Moderate pain |

5.25***

(3.67–7.51) |

5.16***

(3.60–7.40) |

2.18***

(1.67–2.84) |

2.25***

(1.70–2.99) |

||

| Severe pain |

11.69***

(7.67–17.8) |

11.06***

(7.08–17.3) |

2.53***

(1.70–3.75) |

2.46***

(1.61–3.75) |

||

| Insurance (ref.: Medicare) | ||||||

| Medicare plus private insurance | 1.21 (0.77–1.89) |

1.29 (0.80–2.07) |

0.87 (0.69–1.08) |

0.85 (0.65–1.10) |

||

| Medicare plus Medicaid |

2.36***

(1.57–3.54) |

1.59*

(1.00–2.54) |

1.54**

(1.15–2.07) |

1.44*

(1.06–1.96) |

||

Note: “Bivariate” columns show results from unadjusted bivariate logistic regressions for each predictor variable. Models 1–4 are multivariable models simultaneously including all indicated variables plus age categories. Odds ratios significant at 0.05 or less are bolded. CI = confidence interval; Rx = prescription. Supplementary Appendix A presents the same results without sample-weight adjustment.

†p ≤ .10, *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001; two-tailed.

Results from Model 1, which simultaneously includes all sociodemographic predictors, indicate that net of other variables, non-Hispanic blacks had significantly lower odds of prescription opioid use than non-Hispanic whites (OR = 0.57 [95% CI: 0.39–0.85]; p < .01). Wealth remained a strong and significant predictor of opioid consumption. Compared to members of the bottom wealth quartile, those in the top quartile had less than half the odds of using opioids (OR = 0.49 [95% CI: 0.28–0.83]; p < .01), with ORs nearly as small for quartiles 2 and 3 (p < .05 in both cases). Wealth differences manifested primarily as contrasts between the bottom quartile and higher quartiles: supplementary analyses confirm that differences across quartiles 2–4 were not significant. No significant differences by sex, marital status, or education were found net of other sociodemographic variables; indeed, ORs for education dummies were very close to 1.

Model 2 adds pain and health insurance variables as covariates. In this saturated model, 2004 pain was significantly, strongly, and monotonically associated with 2005 opioid use, and Medicaid coverage also predicted opioid use. Although, as noted earlier, findings from nested logistic regressions generally cannot be directly compared (Mood, 2010), the KHB method calculates the rescaling factor between Models 1 and 2 as being very close to 1 (0.97). In this specific case, then, a general comparison of the two models would not be wholly illegitimate—and such comparison suggests that pain and Medicaid partially mediate the association between wealth and opioid use, since in Model 2 all wealth dummies moved closer to 1, and in some cases cease to be statistically significant. This mediation hypothesis is formally tested and confirmed in the next section.

Sensitivity analyses (not shown) revealed that key findings were replicated when treating long-term (6+ months) prescription opioid use as the outcome. This is perhaps unsurprising, since more than 70% of opioid users in this sample were long-term users. Similarly, when cases of cancer pain were excluded, findings scarcely changed, reflecting that only 2.7% of pain cases were potentially attributable to cancer. In models including binary measures of arthritis, back pain, persistent headache, cancer, and diabetes, the first three were significant predictors of opioid use; wealth and pain remained significant predictors as well. Indicators of place of residence as urban, suburban, or ex-urban were never significant, and had no meaningful effect on other findings. Finally, when income quartiles were included instead of wealth quartiles, they showed a negative but relatively weak and not always significant association with opioid use. When included in addition to wealth, only wealth emerged as a significant predictor. In short, wealth was a stronger, more consistent predictor of opioid use than income.

Mediation Tests

Table 3 presents results of KHB analyses of pain level and Medicaid coverage as mediators of the association between low (bottom quartile) wealth and prescription opioid use. Both pain and Medicaid were found to be statistically significant mediators, explaining 23.34% and 20.39%, respectively, of the association. When entered into the model together, they explained 38.37% of the association between low wealth and opioid use, with the OR of this indirect (mediated) pathway estimated at 1.23 (95% CI: 1.11–1.37; p < .001). Thus, while pain level and Medicaid enrollment did help explain low wealth’s association with prescription opioid use, they explained less than half of the association; other unmeasured factors must also have been at play.

Table 3.

KHB Tests of Pain Level and/or Medicaid Coverage as Mediators of the Association Between Low Wealth and Prescription Opioid Use (N = 3,721)

| Mediator: pain level | Mediator: Medicaid coverage | Mediators: pain and Medicaid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent explained | 23.34 | 20.39 | 38.37 |

| Indirect effect as odds ratio (95% CI) |

1.14***

(1.06–1.22) |

1.12**

(1.04–1.20) |

1.23***

(1.11–1.37) |

Note: All models use the logit link function, and control for age categories, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education. “Low wealth” = bottom wealth quartile. Confidence intervals (CIs) calculated via bootstrapping. Odds ratios significant at 0.05 or less are bolded.

**p < .01, ***p < .001; two-tailed.

Predictors of Prescription NSAID Use

If lower rates of opioid use among wealthier respondents represented a general avoidance of pharmacological pain treatments, then one would expect a negative association between wealth and NSAID use as well. However, as shown in Table 2, right half, differences in NSAID use by wealth quartile were less stark than differences in opioid use, and did not show a monotonic pattern. Respondents in the second and third quartiles did show somewhat reduced odds of NSAID use, in both bivariate and multivariable models, but these differences were not significant at an alpha of .05 (in sample-weight adjusted models). However, there appeared to be a tendency for the wealthiest respondents to have higher rates of NSAID use than the least wealthy. This association was not significant at the .05 level in the Table 2 models (but was significant in an unweighted, saturated model: Model 4B in Appendix A.)

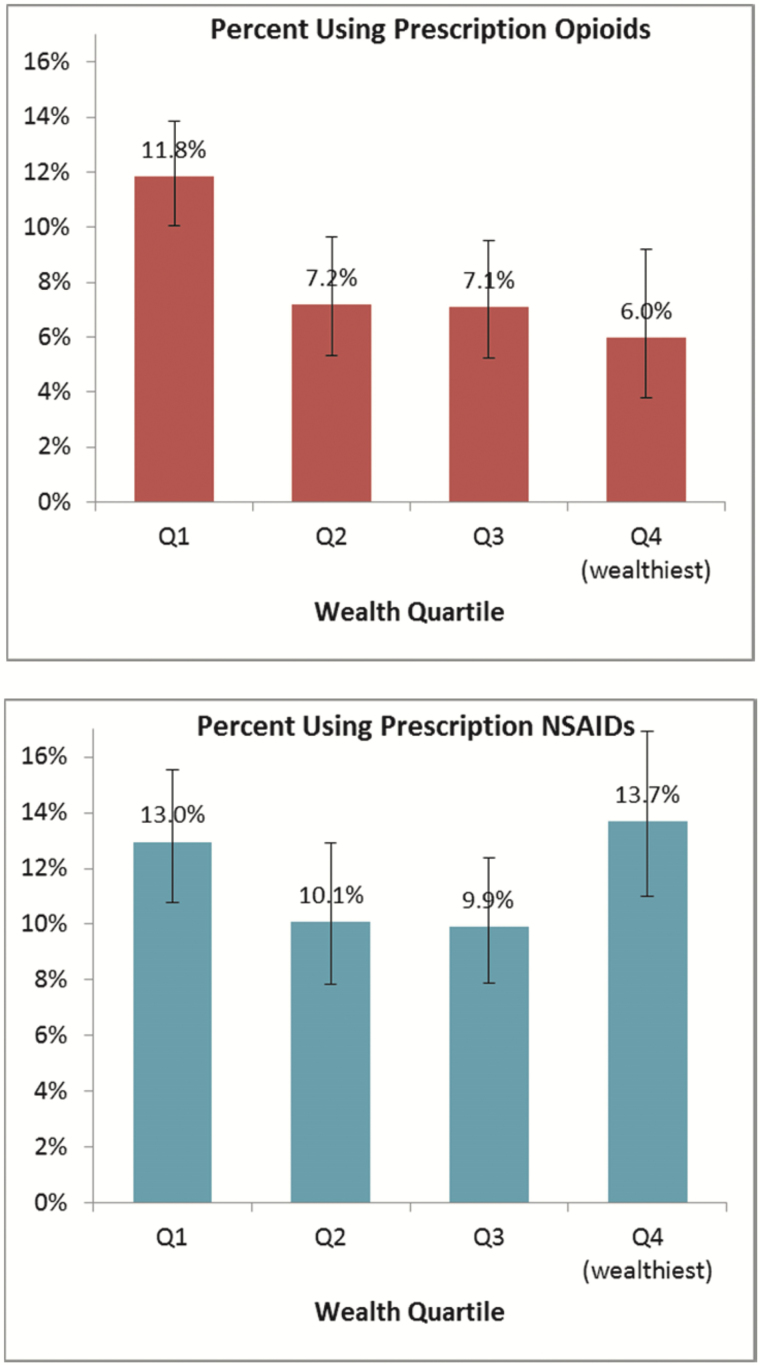

Figure 1 presents the sample-weight adjusted percentage of older U.S. adults in each wealth quartile using prescription opioids (top) and NSAIDs (bottom). This graph shows that opioid use was substantially more common in the least wealthy group than in others (p < .05 in all cases); indeed, it was nearly twice as common in the bottom quartile as in the top quartile (11.8% vs 6.0%). For NSAIDs, there were no significant differences by wealth quartile, and to the extent that a pattern emerged, it was a curvilinear one: the highest rate of NSAID use was in quartile 4 (13.7%), followed closely by quartile 1 (13.0%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of U.S. adults aged 65+ using prescription opioids (top) and prescription NSAIDS (bottom) at time of survey, by wealth quartile, with 95% confidence intervals. N = 3,721; sample-weight adjusted.

Returning to Table 2, significant positive predictors of NSAID use in bivariate analyses were Hispanic or other non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, moderate or severe pain, and Medicaid coverage. In Model 3, which included all sociodemographic variables, Hispanics were again found to have significantly higher odds of NSAID use than whites. In the saturated model (Model 4), moderate and severe pain as well as Medicaid were significant, positive predictors of NSAID use even net of other variables. As with opioids, education was not a significant predictor of NSAID use in any model.

Opinions of Prescription Analgesics

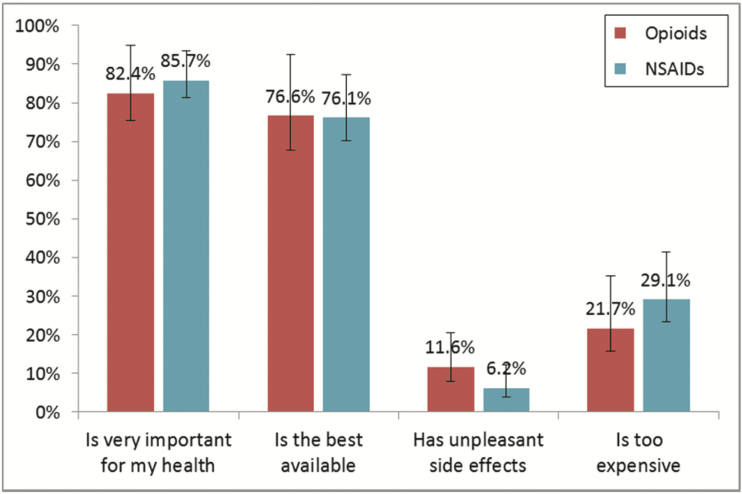

Figure 2 shows the sample-weight adjusted percentages of prescription analgesic users who agreed that the drug they were taking was very important for their health, was the best one available, often gave unpleasant side effects, or was too expensive. Two key points emerge from this figure. First, users of both prescription opioids and prescription NSAIDs were generally quite content with their drugs. More than 80% deemed them “very important,” more than 75% considered them “the best one available,” few (less than 12%) reported unpleasant side effects, and a minority (roughly a quarter) found them too expensive. Second, opinions were very similar for the two classes of drugs, which had overlapping confidence intervals for each opinion statement.

Figure 2.

Percentage of prescription opioid and prescription NSAID users, aged 65+, agreeing with select statements about the drugs, with 95% confidence intervals. Ns between 196 and 409; sample-weight adjusted.

These opinion items may not directly address safety concerns (unless respondents interpreted “side effects” to include risk of addiction or overdose, etc.), but they do indicate that users of both opioids and NSAIDS overall saw their drugs as important, effective, and having relatively few undesirable health consequences. There is no indication that opioids were widely viewed as a subpar or problematic treatment in the mid-2000s.

Moreover, these sanguine assessments were common to all sociodemographic groups. Analyses regressing opinions of drugs on the same sociodemographic variables used in Model 2 reveal very few significant differences in opinions by sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, or wealth (Supplementary Appendices B and C). Exceptions were that less wealthy individuals were more likely to deem opioids “very important” for their health, and that women were more likely than men to report bad side effects and excessive costs of NSAIDs. Otherwise, no significant differences in agreement with the statements were found (although this could reflect limited statistical power).

Discussion

This study examined sociodemographic predictors of prescription opioid use among retirement-age adults in the mid-2000s. As in Frenk and colleagues (2015a, 2015b), bivariate analyses indicated that income was inversely associated with prescription opioid use. Predictors of prescription opioid use also sometimes resembled predictors of misuse or overdose identified in prior studies, for example, Medicaid enrollment (Fernandes et al., 2015; Rigg & Monnat, 2015). However, a number of the present findings differ from those of earlier studies. Rigg and Monnat’s (2015) finding that prescription opioid misuse is more common in urban regions was not paralleled by findings of urban–rural differences in use in the present study. Frenk and colleagues’ (2015a) observation in all-age adult data of lower opioid use among Hispanics (but not blacks) vis-à-vis whites was not replicated, suggesting that racial/ethnic patterns may differ across age groups. Such differences across studies underscore that predictors of prescription opioid use may well differ from predictors of misuse, and that observed patterns may depend on sample characteristics including age range and period of data collection.

The strongest socioeconomic predictor of prescription opioid use in this study, in both bivariate and multivariable models, was low wealth. Indeed, those in the bottom wealth quartile were approximately twice as likely to use opioids as those in the top quartile. The hypothesis that health care providers would be more likely to trust and hence prescribe opioids to high-SES individuals was not supported; instead, opioids were prescribed disproportionately to the socioeconomically less advantaged. This is unlikely to reflect deliberate selection out of opioid use by the more educated, since no significant educational differences in use or opinions of opioids were found. Nor did avoidance of pharmacological treatments in general appear to explain wealth differences in opioid use, since when it came to prescription NSAIDs, there was no negative association between wealth and use.

Why, then, was low wealth associated with elevated rates of prescription opioid use? Two potential mediators, pain level and Medicaid coverage, were tested. Both were found to be significant mediators of the low-wealth–opioid use link, but together explained only 38.37% of the association. That is, while the least wealthy did experience more pain, and were more likely to have Medicaid coverage, these facts only partially explained their higher rates of opioid use. Other potential explanations cannot be tested with current data. For example, perhaps causes of pain differed across wealth levels, driving observed prescription patterns, or perhaps less wealthy individuals saw providers more inclined to prescribe opioids, for example, doctors graduating from lower-ranked medical schools (Schnell & Currie, 2018).

Medicaid enrollment predicted prescription opioid use in this sample even though all respondents were eligible for Medicare (which also covers opioids). This link between Medicaid and opioid use must be interpreted cautiously. Dual eligibility (i.e., for both Medicare and Medicaid) is a marker not only of low resources but also of high levels of illness and/or disability. The health profiles of Medicaid enrollees might have seemed to warrant high rates of opioid prescription given the treatment protocols of the time. A less benign possibility is that Medicaid contributed to the diffusion of a potentially dangerous class of drugs by covering prescription opioids rather than safer (e.g., nonpharmacological) pain treatments. (Historically, Medicaid programs have not covered nonpharmacological treatments such acupuncture. This has been changing in recent years; at present, 12 states cover such alternative therapies; Ross, 2018.) Regardless, it is important to note that since the implementation of Medicare Part D in 2006, Medicare, not Medicaid, has become the largest public payer for opioids (Zhou, Florence, & Dowell, 2016).

Why was low wealth a stronger predictor of opioid use than either low income or education? Compared with income, wealth is a more accurate, stable measure of socioeconomic standing, especially among retirement-age adults (Grol-Prokopczyk, Freese, & Hauser, 2011; Whillans & Nazroo, 2018). (Wealth is also a more challenging measure to collect, which may explain its rarity in studies of opioid use or misuse, despite its predictive utility.) Regarding education, the analysis of drug opinions may hint as to why it failed to significantly predict opioid use: across all levels of education, analgesic users overwhelmingly agreed that opioids (and NSAIDs) were “very important for [their] health” and “the best available” drug, and rarely reported unpleasant drug-related side effects. There was no educational gradient in opioid-related opinions.

These positive opinions suggest that beliefs about opioids during the mid-2000s may indeed have been analogous to beliefs about cigarettes in the 1950s (Link, 2008), that is, in the early stages of what might be termed an informational transition. That is, despite occasional news stories or medical articles about opioids’ risks, such information was not widely known and/or believed by any social group. However, as information about opioids’ risks reaches a critical mass in the United States (as it arguably has in the last half-decade), clear educational gradients in opioid-related beliefs and behaviors may yet emerge, as more educated individuals “take advantage of the new knowledge” (Phelan et al., 2010). If smoking is an example (Link, 2008), such gradients may persist for some time to come.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the PDS asked only about current prescription drug use, and thus likely underestimates the percentage of older adults ever or recently exposed to opioids. (Estimates of annual rates of prescription opioid use for 2005–2006, for all-age adults, are indeed higher—in the range of 15%–20% depending on racial/ethnic group; Harrison et al., 2018.) The key outcome measure in this study is admittedly crude: prescription opioid use treated as a binary variable (i.e., without regard to dosage). This study is thus unable to draw conclusions about opioid dosage, misuse, addiction, or illicit use among older adults. In addition, only current users of a drug were asked their opinions of the drug, reducing sample size and statistical power, and potentially introducing bias: Individuals who opted to discontinue or not take drugs, perhaps because of quality or safety concerns, were effectively censored. These data may thus overstate satisfaction with opioids and/or NSAIDs.

Additional limitations include that all drug data were self-reported, which raises the possibility of reporting inaccuracies. (For example, although the PDS questionnaire made very clear that it sought information about prescription drugs—including by requesting information directly from prescription labels—some respondents may have entered over-the-counter NSAID information, leading to overestimation of prescription NSAID use.) However, self-report also has advantages: since some individuals fill prescriptions “just in case” but do not use them, pharmacy data may overestimate actual use. As mentioned, patients’ specific health conditions likely shape observed drug use patterns. However, because the HRS lacks data on causes of respondents’ pain, this study could not accurately assess clinical conditions as predictors of analgesic use. Lack of information on respondent geography is also a limitation, since prescription opioid use emerged most heavily in specific, often low-SES regions (Quinones, 2015). Present findings on patterns in opioid use may be biased if PDS respondents disproportionately represent such regions.

Finally, as noted, patterns found among adults age 65+ may not generalize to younger groups. For example, given that college completion rates are lower in older than younger generations, the lack of significant educational differences in use or opinions of opioids shown here might not be replicated in younger samples. Such hypotheses could be empirically tested in data with a broader age range. Regardless, older adults are worthy of study in their own right, especially given their high rates of chronic pain and the possibility that underclassification of opioid-related deaths (Ray et al., 2016) is particularly likely in this age group.

This study is based on data from a specific point in time. Since patients’ and providers’ opioid-related beliefs and behaviors have changed substantially in the past decade—as reflected by the 18% reduction in opioid prescriptions between 2010 and 2015 alone (Goodnough, 2017)—the social patterns reported herein have quite likely already changed, and will continue to do so.

In particular, social gradients in opioid use may steepen in the coming years, for reasons relating to both education and income/wealth. First, as noted, the weak correlation between education and opioid use in the mid-2000s has likely strengthened. Information about opioids is now ubiquitous, and those with more education may be better able to access and interpret emerging findings about how to avoid or minimize opioid-related risks. Second, alternatives to opioid therapy touted in recent government and medical reports, such as physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and biofeedback (The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, 2017; Volkow & McLellan, 2016), may be financially or temporally out of reach to the poor, especially if undercovered or not covered by health insurance (Ross, 2018). This may leave the poor as disproportionate users of opioids (perhaps prescribed, perhaps illicit) out of perceived necessity rather than out of choice.

Health care providers and policy makers would do well to acknowledge that many chronic opioid users have been very content with their drugs, as the opinion data in this study show, and that socioeconomically disadvantaged patients—the very group most likely to use prescription opioids—may have limited options for alternate pain treatments. Providers and policy makers might also consider the argument that the United States is simultaneously experiencing an opioid crisis and a crisis of undertreated pain (Carr, 2016). To shut the door to one form of pain treatment without ensuring that others are open will likely exacerbate the latter crisis, and perhaps the former too, if those unable to access prescribed drugs switch to illicit ones. Continued analysis of social patterns in use of opioids and other pain treatments could help shape effective responses to both the opioid and pain crises, by helping to ensure that relevant information and safe pain management are available to all sociodemographic groups.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data materials are available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

This research was supported by the Network on Life Course Health Dynamics and Disparities in 21st Century America (NLCHDD) via grant # R24AG045061 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health. The NLCHDD received additional support for its annual meetings from the Michigan Center on the Demography of Aging (MiCDA) via NIA grant # P30AG012846. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

I thank Yulin Yang for her assistance in coding the prescription drug data, and Wei Luo for her research on the KHB method. I am also grateful to Robert Adelman, Ashley Barr, Chris Dennison, Erin Hatton, Kristen Schultz Lee, Jesse Norris, Jessica Houston Su, and Mary Nell Trautner for helpful comments on this project.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bajwa Z. H., Wootton R. J., & Warfield C. A (Eds.). (2017). Principles and practice of pain medicine (3rd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. B. (2016). NPS versus CDC: Scylla, Charybdis and the “number needed to [under-] treat”. Pain Medicine, 17, 999–1000. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Vitalsigns (2011). Prescription painkiller overdoses in the US Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/painkilleroverdoses/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees—Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR, 58, 1171–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. H., Hedegaard H., & Warner M (2014). Drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics: United States, 1999–2011. NCHS Data Brief, 166 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db166.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clines F. X., & Meier B (2001, February 9). Cancer painkillers pose new abuse threat. The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2001/02/09/us/cancer-painkillers-pose-new-abuse-threat.html [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J. C., Campana D., Harwell T. S., & Helgerson S. D (2015). High mortality rate of unintentional poisoning due to prescription opioids in adults enrolled in Medicaid compared to those not enrolled in Medicaid in Montana. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 153(Suppl. C), 346–349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk S. M., Porter K. S., & Paulozzi L. J (2015a). Prescription opioid analgesic use among adults: United States, 1999–2012. NCHS data brief, no 189. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk S. M., Porter K. S., & Paulozzi L. J (2015b). Use of prescription opioid analgesics in the preceding 30 days among adults aged ≥20 years, by poverty level and sex. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 427. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E. M. Karlamangla A. S. Gruenewald T. L. Koretz B. & Seeman T. E (2015). Early life adversity and adult biological risk profiles. Psychosomatic Medicine, 77, 176–185. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnough A. (2017, July 7). Report finds a decline in opioid prescriptions after a 2010 peak. The New York Times, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Grol-Prokopczyk H. (2017). Sociodemographic disparities in chronic pain, based on 12-year longitudinal data. Pain, 158, 313–322. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol-Prokopczyk H. Freese J. & Hauser R. M (2011). Using anchoring vignettes to assess group differences in general self-rated health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 246–261. doi: 10.1177/0022146510396713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J. M. Lagisetty P. Sites B. D. Guo C. & Davis M. A (2018). Trends in prescription pain medication use by race/ethnicity among US adults with noncancer pain, 2000–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 108, 788–790. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study (2008a). 2005 Prescription Drug Study data description and usage Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/pds/pds2005/desc/pds2005dd.pdf

- Health and Retirement Study (2008b). Sample evolution: 1992–1998 Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/surveydesign.pdf

- Joranson D. E. Ryan K. M. Gilson A. M. & Dahl J. L (2000). Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA, 283, 1710–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joynt M. Train M. K. Robbins B. W. Halterman J. S. Caiola E. & Fortuna R. J (2013). The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status and race on the prescribing of opioids in emergency departments throughout the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 1604–1610. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2516-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler U., Karlson K. B., & Holm A (2011). Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. Stata Journal, 11, 420–438. [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G. (2008). Epidemiological sociology and the social shaping of population health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 367–384. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier D. E. (2001, March 9). The trajectory of a painkiller (Letter to Editor). The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2001/03/09/opinion/l-the-trajectory-of-a-painkiller-320129.html [Google Scholar]

- Meier B., & Petersen M (2001, March 5). Sales of painkiller grew rapidly, but success brought a high cost. The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2001/03/05/business/sales-of-painkiller-grew-rapidly-but-success-brought-a-high-cost.html [Google Scholar]

- Montez J. K. & Friedman E. M (2015). Educational attainment and adult health: Under what conditions is the association causal?Social Science & Medicine (1982), 127, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mood C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26, 67–82. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp006 [Google Scholar]

- Morasco B. J. Yarborough B. J. Smith N. X. Dobscha S. K. Deyo R. A. Perrin N. A. & Green C. A (2017). Higher prescription opioid dose is associated with worse patient-reported pain outcomes and more health care utilization. The Journal of Pain, 18, 437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja P., Bugliari D., Campbell N., Chan C., Hayden O., Hurd M., … St. Clair P (2016). RAND HRS Income and Wealth Imputations, Version P Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/rand/randincwlth/randiwp.pdf

- Phelan J. C. Link B. G. & Tehranifar P (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl), S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher M. J. Kertesz S. G. Kohn M. A. & Gonzales R (2008). Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA, 299, 70–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones S. (2015). Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ray W. A. Chung C. P. Murray K. T. Hall K. & Stein C. M (2016). Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA, 315, 2415–2423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg K. K. & Monnat S. M (2015). Urban vs. rural differences in prescription opioid misuse among adults in the United States: Informing region specific drug policies and interventions. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26, 484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. (2018, January 17). As the opioid crisis grows, states are opening Medicaid to alternative medicine. Stat News. Retrieved from https://www.statnews.com/2018/01/17/medicaid-opioids- alternative-medicine/ [Google Scholar]

- Rudd R. A. Aleshire N. Zibbell J. E. & Gladden R. M (2016). Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer J. F., Salas J., Copeland L. A., Stock E. M., Schneider F. D., Sullivan M.,…, Lustman P. J. (2016). Increased risk of depression recurrence after initiation of prescription opioids in noncancer pain patients. The Journal of Pain, 17, 473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell M., & Currie J (2018). Addressing the opioid epidemic: Is there a role for physician education?American Journal of Health Economics, 4, 383–410. doi: 10.1162/ajhe_a_00113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M. J. & Melnik T. A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2015). Poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics—New York State, 2003–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 377–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A. Fuino R. L. Pesis-Katz I. Cai X. Powers B. Frazer M. & Markman J. D (2017). Differences in opioid prescribing in low back pain patients with and without depression: A cross-sectional study of a national sample from the United States. Pain Reports, 2, e606. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis (2017). Final report draft Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Final_Report_Draft_11-15–2017.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Volkow N. D. & McLellan A. T (2016). Opioid abuse in chronic pain—Misconceptions and mitigation strategies. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 1253–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield C. A., & Bajwa Z. H (Eds.). (2004). Principles and practice of pain medicine (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Whillans J., & Nazroo J (2018). Social inequality and visual impairment in older people. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, 532–542. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese A. D. Griffin M. R. Stein C. M. Mitchel E. F. Jr., & Grijalva C. G (2016). Opioid analgesics and the risk of serious infections among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A self-controlled case series study. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.), 68, 323–331. doi: 10.1002/art.39462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R., & Johnson D. R (2012). To weight, or not to weight, that is the question: Survey weights and multivariate analysis. Paper presented at the The American Association for Public Opinion Research Annual Conference, Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C. Florence C. S. & Dowell D (2016). Payments for opioids shifted substantially to public and private insurers while consumer spending declined, 1999–2012. Health Affairs, 35, 824–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.