Gene transfer agents (GTAs) are virus-like particles that move cellular DNA between cells. In the alphaproteobacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus, GTA production is affected by the activities of multiple cellular regulatory systems, to which we have now added signaling via the second messenger dinucleotide molecule bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP). Similar to the CtrA phosphorelay, c-di-GMP also affects R. capsulatus flagellar motility in addition to GTA production, with lower levels of intracellular c-di-GMP favoring increased flagellar motility and gene transfer. These findings further illustrate the interconnection of GTA production with global systems of regulation in R. capsulatus, providing additional support for the notion that the production of GTAs has been maintained in this and related bacteria because it provides a benefit to the producing organisms.

Keywords: gene exchange, regulation, diguanylate cyclase, phosphodiesterase, GGDEF, EAL

ABSTRACT

Gene transfer agents (GTAs) are bacteriophage-like particles produced by several bacterial and archaeal lineages that contain small pieces of the producing cells’ genomes that can be transferred to other cells in a process similar to transduction. One well-studied GTA is RcGTA, produced by the alphaproteobacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. RcGTA gene expression is regulated by several cellular regulatory systems, including the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay. The transcription of multiple other regulator-encoding genes is affected by the response regulator CtrA, including genes encoding putative enzymes involved in the synthesis and hydrolysis of the second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP). To investigate whether c-di-GMP signaling plays a role in RcGTA production, we disrupted the CtrA-affected genes potentially involved in this process. We found that disruption of four of these genes affected RcGTA gene expression and production. We performed site-directed mutagenesis of key catalytic residues in the GGDEF and EAL domains responsible for diguanylate cyclase (DGC) and c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) activities and analyzed the functions of the wild-type and mutant proteins. We also measured RcGTA production in R. capsulatus strains where intracellular levels of c-di-GMP were altered by the expression of either a heterologous DGC or a heterologous PDE. This adds c-di-GMP signaling to the collection of cellular regulatory systems controlling gene transfer in this bacterium. Furthermore, the heterologous gene expression and the four gene disruptions had similar effects on R. capsulatus flagellar motility as found for gene transfer, and we conclude that c-di-GMP inhibits both RcGTA production and flagellar motility in R. capsulatus.

IMPORTANCE Gene transfer agents (GTAs) are virus-like particles that move cellular DNA between cells. In the alphaproteobacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus, GTA production is affected by the activities of multiple cellular regulatory systems, to which we have now added signaling via the second messenger dinucleotide molecule bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP). Similar to the CtrA phosphorelay, c-di-GMP also affects R. capsulatus flagellar motility in addition to GTA production, with lower levels of intracellular c-di-GMP favoring increased flagellar motility and gene transfer. These findings further illustrate the interconnection of GTA production with global systems of regulation in R. capsulatus, providing additional support for the notion that the production of GTAs has been maintained in this and related bacteria because it provides a benefit to the producing organisms.

INTRODUCTION

Gene transfer between cells plays an important role in bacterial evolution, with horizontal gene transfer (HGT) being the main force behind the acquisition of new, adaptive traits and genetic variation among bacterial strains (1). In addition to the three canonical mechanisms by which bacterial DNA exchange occurs, i.e., transformation, conjugation, and transduction, a different type of genetic exchange process is mediated through bacteriophage-like particles called gene transfer agents (GTAs). This gene transfer mechanism resembles the process of transduction, but GTAs are distinct from transducing bacteriophages (2, 3). Similar to prophages, GTAs are encoded by genes within the producing organisms’ genomes. However, GTAs are distinct from induced transducing prophages, because all GTA particles contain only DNA from the cells’ genomes. They also package less DNA than required to encode the GTA particles, making them incapable of self-transmission (2, 3).

Gene transfer agents are known to be produced by multiple bacteria and one archaeon (4, 5). The first-discovered GTA (now known as RcGTA) is produced by Rhodobacter capsulatus (6), a purple nonsulfur alphaproteobacterium that has been used as a model organism for various aspects of physiology, such as anoxygenic photosynthesis (7). Each RcGTA particle packages approximately 4 kb of double-stranded DNA (8), while the main gene cluster encoding the particles spans approximately 14 kb (9). Additional genes required for RcGTA production, function, and release are located at distinct locations in the genome (10–12). The expression of the RcGTA genes is regulated by several cellular signaling systems, as well as phage-related regulators (4, 13). The cellular regulators include the CckA-ChpT-CtrA phosphorelay (9, 14), the GtaI-GtaR quorum-sensing system (15, 16), the Rba partner-switching phosphorelay (17), the SOS regulator LexA (18), and the PAS domain protein DivL (19).

The CtrA response regulator protein was first characterized in Caulobacter crescentus (20), where it acts as a master regulator of the cell cycle (21). Among all cellular RcGTA regulators identified to date, only the loss of CtrA causes a complete loss of RcGTA production, which is caused by the loss of transcription of most genes in the RcGTA gene cluster (9, 22). The loss of a phage-derived regulator gene (11), which has been renamed gafA (13), also causes a complete loss of GTA production, and this gene is also regulated by CtrA. Transcriptomic studies in R. capsulatus revealed that more than 225 genes are dysregulated in the absence of CtrA (22), including more than 20 genes predicted to encode proteins involved in signal transduction or the regulation of gene expression. These include proteins predicted to be involved in signaling via the second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP), based on the presence of conserved domains for c-di-GMP synthesis or degradation.

Cyclic di-GMP is a ubiquitous second messenger that controls various aspects of bacterial physiology (23, 24). Cyclic di-GMP binds to a range of targets, including riboswitches and proteins, and affects diverse processes, including motility, biofilm formation, virulence, and cell cycle progression. Inhibition of motility and promotion of a sessile lifestyle and biofilm formation are the most widely conserved behaviors in bacteria in response to elevated levels of c-di-GMP. Two GTP molecules are used for the synthesis of c-di-GMP, catalyzed by diguanylate cyclase (DGC) enzymes that contain GGDEF motifs in their active sites (A sites) (25–27). In addition to an A site, many DGCs also carry an inhibitory site (I site) motif, RXXD, which is involved in feedback inhibition (28, 29). Cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs), characterized by EAL (30–32) and HD-GYP (33) domains, break down c-di-GMP into 5′-phosphoguanylyl-(3′-5′)-guanosine (pGpG). Some proteins contain both GGDEF and EAL domains and can be bifunctional (34, 35). It is also possible that only one domain is enzymatically active in such dual-domain proteins, and enzymatically inactive domains can often bind former substrates, c-di-GMP (EAL) (36) or GTP (GGDEF) (31), and serve as regulatory sites (37). The GGDEF and EAL domains are often present within proteins that contain additional periplasmic, membrane-embedded, or cytoplasmic ligand-binding/signaling domains. These include the response regulator receiver (REC) domain and ligand-binding domains like Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) and cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases/adenylyl cyclases/FhlA (GAF) (37).

The R. capsulatus genome (7) carries 20 genes predicted to encode proteins containing GGDEF or EAL domains, and the transcript levels of 9 of these genes were significantly decreased in a ctrA null mutant (22). Based on this observation, we hypothesized that c-di-GMP signaling might affect the production of RcGTA. We have investigated the possible roles of the eight chromosomally encoded putative c-di-GMP signaling proteins from this group (Table 1) in R. capsulatus gene exchange. We evaluated the potential enzymatic activities of the four of these proteins that were implicated in RcGTA production via phenotypic assays in Escherichia coli. We also investigated the effects of changes in cellular levels of c-di-GMP on R. capsulatus gene exchange. In addition, we investigated the roles of these genes and c-di-GMP in R. capsulatus flagellar motility and concluded that elevated c-di-GMP levels inhibit RcGTA production and flagellar motility in this bacterium.

TABLE 1.

Properties of eight chromosomal c-di-GMP signaling genes whose transcript levels are affected by loss of CtrA

| Gene | Transcript fold change in ctrA null mutanta | Protein accession no. | Size of protein (aa) | c-di-GMP domain(s) | Additional domainb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rcc00346 | −7.6 | ADE84111.1 | 514 | GGDEF, EAL | |

| rcc00620 | −14.0 | ADE84385.1 | 610 | GGDEF, EAL | REC |

| rcc00645 | −7.7 | ADE84410.1 | 1,245 | GGDEF, EAL | PAS |

| rcc02539 | −8.1 | ADE86269.1 | 641 | GGDEF, EAL | |

| rcc02629 | −8.1 | ADE86359.1 | 353 | GGDEF | |

| rcc02857 | −12.5 | ADE86586.1 | 1,158 | GGDEF, EAL | PAS |

| rcc03177 | −19.5 | ADE86901.1 | 280 | EAL | |

| rcc03301 | −4.5 | ADE87025.1 | 1,284 | GGDEF, EAL | PAS |

From reference 22.

REC, response regulator receiver; PAS, Per-ARNT-Sim.

RESULTS

Disruptions of four genes encoding predicted c-di-GMP signaling proteins affect RcGTA production.

Insertional disruptions were made in the eight chromosomal genes predicted to encode c-di-GMP signaling proteins whose mRNA levels were affected by the loss of CtrA (Table 1), which is a key regulator required for RcGTA gene expression. The strains with disruptions in four genes, rcc00620, rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857, showed appreciable differences in RcGTA production relative to the level in the parental strain, whereas the other four gene disruptions did not (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Disruption of rcc00620 decreased RcGTA production, whereas disruptions in rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857 increased it.

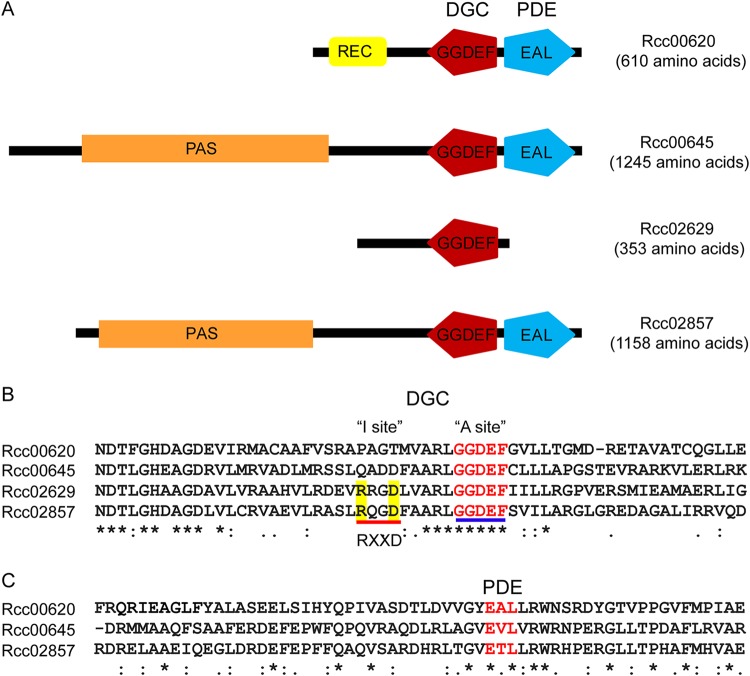

Evaluation of the protein sequences for the four genes showed that Rcc00620, Rcc00645, and Rcc02857 contained both GGDEF and EAL domains, while Rcc02629 contained only a GGDEF domain (Fig. 1A). Amino acid sequence analysis revealed that the GGDEF domains of all four proteins have all of the conserved residues required for DGC activity (Fig. 1B) (23). Similarly, the EAL domains of Rcc00620, Rcc00645, and Rcc02857 contain all of the conserved residues required for PDE activity (Fig. 1C) (23). Therefore, Rcc02629 may possess DGC activity, while the three remaining proteins, Rcc00620, Rcc00645, and Rcc02857, may possess either DGC or PDE activity or both activities.

FIG 1.

Predicted domains of four putative c-di-GMP signaling proteins that affect RcGTA gene transfer activity. (A) Locations and organizations of predicted domains identified in the four proteins. The domains are as follows: REC, response regulator receiver; DGC, GGDEF (diguanylate cyclase); PDE, EAL (phosphodiesterase); PAS, Per-ARNT-Sim. (B) Amino acid sequence alignments for the four proteins indicating A (active site; GGDEF, indicated by blue line) and I (inhibitory site; RXXD, indicated by red line) sites for the DGC domains. (C) Amino acid sequence alignments for three of the proteins with the EAL motifs, which represent the PDE domains, indicated in red.

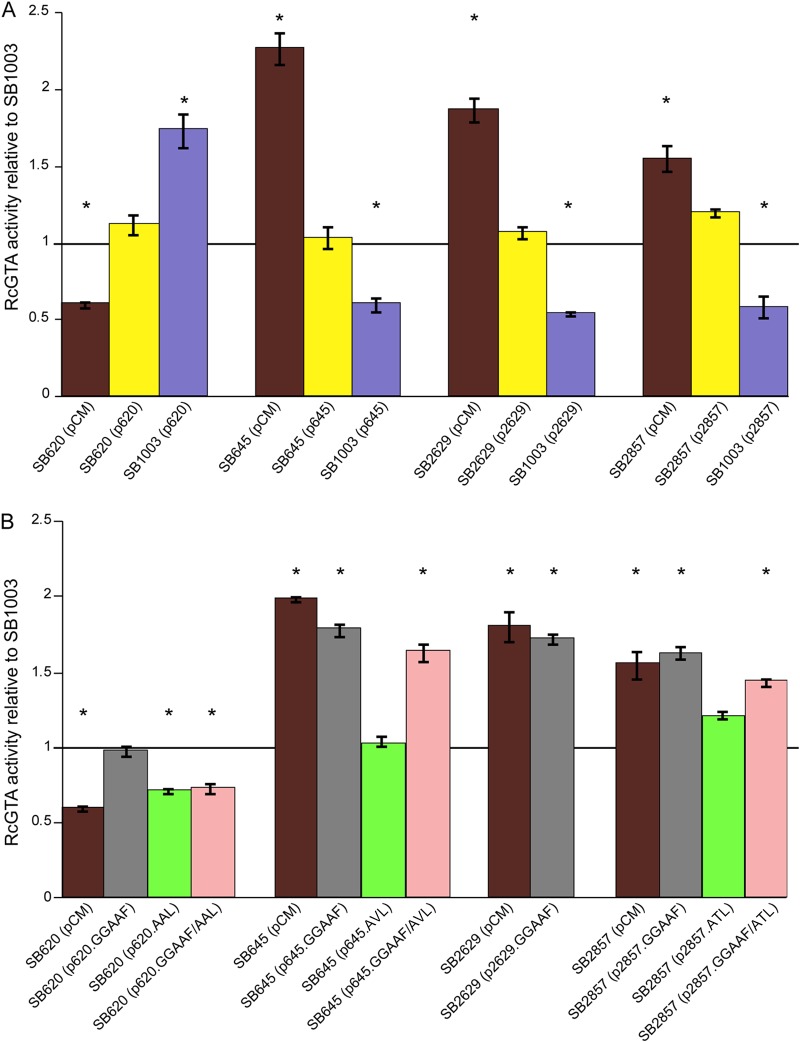

To eliminate the possibility that truncated proteins encoded by the disrupted versions of the rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 genes affected the results, we constructed deletion-insertion (as opposed to insertion-only) mutations, where a large portion of each open reading frame (ORF) was replaced with the KIXX fragment. The newly generated deletion-insertion mutants with mutations in rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 showed essentially the same phenotypes as the original insertion knockouts (Fig. 2A). The original rcc00645 disruption mutant already featured a large deletion of the coding region, therefore obviating the need to construct a new mutant. trans complementation of all four mutants restored RcGTA production to the parental-strain levels (Fig. 2A). The expression of plasmid-borne rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857 in the parental strain reduced RcGTA production (Fig. 2A). These results are consistent with the inhibitory role of Rcc00645, Rcc02629, and Rcc02857 in RcGTA production. The expression of rcc00620 complemented the rcc00620 mutation and increased RcGTA production in the parental strain, consistent with a stimulating role for Rcc00620 in RcGTA production.

FIG 2.

Effects of gene disruptions, trans complementation, and site-directed mutagenesis of enzymatic domains on RcGTA gene transfer activity. The gene transfer activities for mutants and strains containing plasmid-borne copies of the genes (A) and strains containing site-directed mutant versions of the genes (B) are presented as average values from 3 replicates relative to the value for the parental strain, SB1003, carrying the empty vector, pCM62. Error bars represent the standard deviations, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the result for the control, identified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis, are indicated by asterisks.

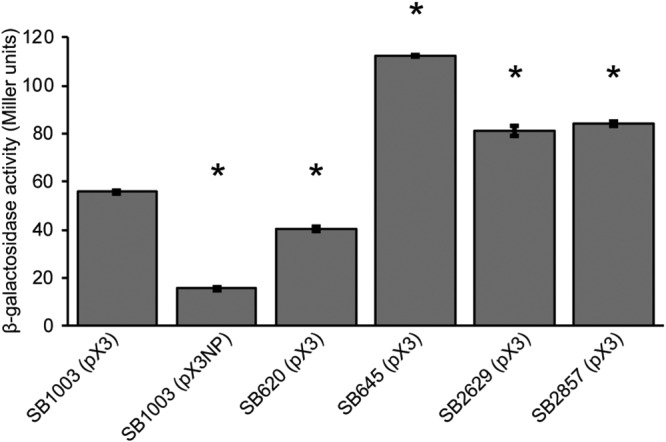

Quantification of gene expression for the RcGTA major structural gene cluster via a reporter fusion showed that the changes in gene transfer activities in the four mutant strains matched with changes in RcGTA gene expression (Fig. 3). Quantification of the amounts of RcGTA major capsid protein within cells and released into the extracellular environment (Fig. S2) also indicated that the observed patterns in RcGTA activities in the mutant strains could be explained by changes in the production and release of RcGTA for all four genes. Also, the relative RcGTA activities and capsid protein levels matched well when these genes were present in either mutant or parental strains. One exception was for rcc02629, where the decreased RcGTA activity observed when rcc02629 was present on the plasmid in parental strain SB1003 (Fig. 2A) did not match with lower capsid protein levels (Fig. S2), although the results for this strain also showed the largest standard deviation in this assay.

FIG 3.

Effects of gene disruptions on RcGTA gene expression. β-Galactosidase activities were measured for the indicated strains carrying the RcGTA orfg3′::′lacZ fusion construct, pX3. SB1003(pX3NP) is the promoterless negative control. The results are the average values from three biological replicates, with error bars representing the standard deviations. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.0001) compared to the result for the control, SB1003(pX3), were identified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis and are indicated by asterisks.

Analysis of GGDEF and EAL domains for the proteins affecting RcGTA production.

To investigate which activities are involved in stimulating and inhibiting RcGTA production, we introduced site-directed mutations in the GGDEF and EAL motifs (Fig. 1) of the proteins of all four proteins to generate GGAAF, AAL/AVL/ATL, and GGAAF+AAL/AVL/ATL derivatives. The site-directed mutant derivatives were introduced into the respective knockout strains, and RcGTA gene transfer activities were assayed. The GGAAF mutation in Rcc00620 had no effect on gene transfer activity, while mutation of the EAL domain (and both GGDEF and EAL domains) abolished the ability of Rcc00620 to complement the rcc00620 mutation (Fig. 2B). This observation suggests that Rcc00620 has PDE activity that stimulates RcGTA production. The GGAAF mutations in Rcc00645, Rcc02629, and Rcc02857 abolished their ability to complement their respective mutations, while mutations in the EAL domains in Rcc00645 and Rcc02629 had little to no effect on complementation (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that Rcc00645, Rcc02629, and Rcc02857 have DGC activities that inhibit RcGTA production in R. capsulatus.

To test the cumulative effect of losses of the suspected DGC-encoding genes on GTA production, an rcc00645 rcc02629 rcc02857 triple-knockout mutant was constructed and tested for RcGTA activity. This strain did show an increase in RcGTA activity relative to those of the individual mutants (Fig. S3). Disruption of both rcc00620 and rcc00645 resulted in gene transfer activity comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. S3), indicating that the loss of these two genes had compensatory effects.

Effects of changing intracellular c-di-GMP levels on RcGTA production.

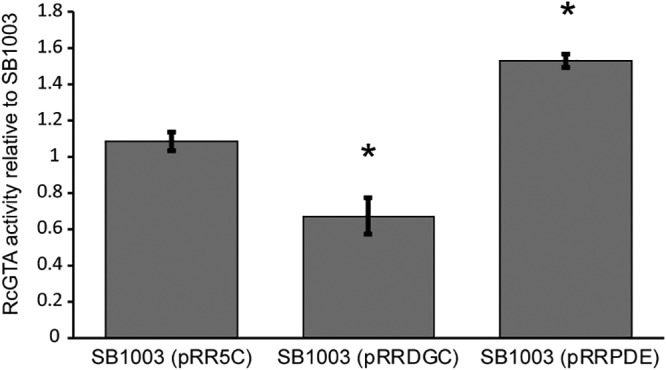

The analyses described above supported the notion that the DGC activities of these R. capsulatus proteins are responsible for reducing RcGTA production, while PDE activity is responsible for stimulating RcGTA production. To test the effects of c-di-GMP levels on RcGTA production more directly, we expressed heterologous genes encoding DGC (Rhodobacter sphaeroides dgcA) and PDE (Gluconacetobacter xylinus pde1) enzymes in R. capsulatus. RcGTA gene transfer assays showed that expression of the PDE caused an approximately 50% increase in RcGTA production, whereas expression of the DGC caused an approximately 40% decrease (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Expression of genes encoding known DGC and PDE enzymes affects RcGTA gene transfer activity. The gene transfer activities for R. capsulatus SB1003 carrying the expression plasmid pRR5C (pRR), pRR5C with pdeA from G. xylinus (pRRPDE), and pRR5C with dgcA from R. sphaeroides (pRRDGC) are presented as average ratios relative to the value for SB1003 carrying no exogenous plasmid. The data come from 3 replicates, with error bars showing the standard deviations, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the value for the control, identified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis, are indicated by asterisks.

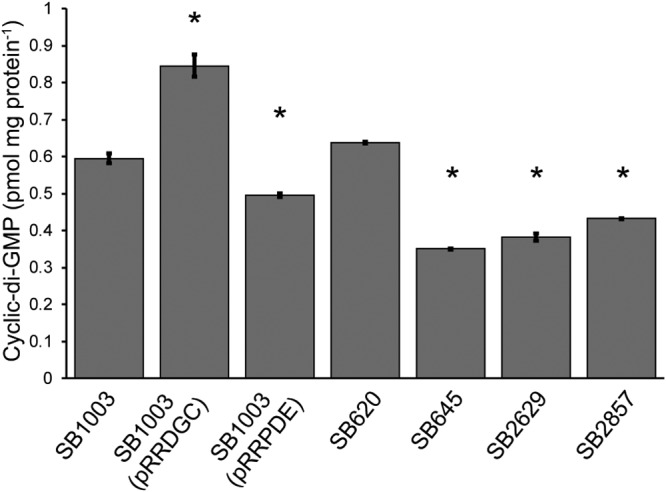

To confirm whether the disruption or expression of the different genes was leading to changes in intracellular c-di-GMP levels, we quantified these in the different strains. The mutant strains and the parental strain with and without the heterologous DGC and PDE genes were cultured under the same conditions as used for the GTA bioassay experiments and subjected to c-di-GMP quantification. Expression of the heterologous PDE resulted in lower levels of c-di-GMP, as did loss of the rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857 genes (Fig. 5). Expression of the heterologous DGC increased the c-di-GMP levels, as did disruption of rcc00620 (Fig. 5), although the difference was not statistically significant for this strain.

FIG 5.

Quantification of intracellular c-di-GMP levels in R. capsulatus strains. c-di-GMP levels were measured by HPLC and normalized to the protein contents of the corresponding cell samples. The data come from 3 replicates, with the error bars representing the standard deviations, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the value for the control, identified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis, are indicated by asterisks.

Assaying R. capsulatus proteins for DGC and PDE activities in E. coli.

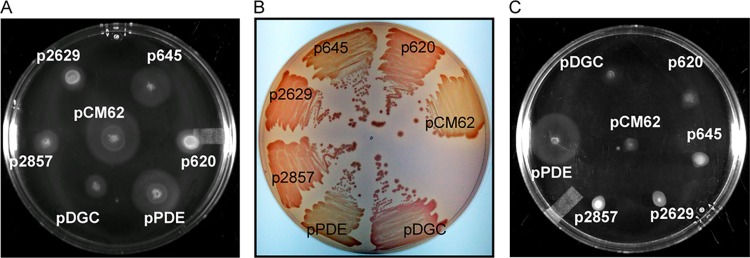

To gain a better understanding of the DGC or PDE activities of the R. capsulatus proteins, we expressed them in the Escherichia coli c-di-GMP reporter strain MG1655, where the expression of an active heterologous DGC that increases the intracellular c-di-GMP levels inhibits swimming motility on semisolid agar (38). The expression of rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 in MG1655 decreased the swim zones compared to that of the empty-vector control (Fig. 6A), indicative of their having DGC activities in E. coli. The expression of rcc00645 had a small inhibitory effect on the swim zone. We also assessed a second c-di-GMP-dependent E. coli phenotype, fimbria production in strain BL21(DE3), which can be detected by Congo red staining (28). The pattern was the same as for the motility assays, with the expression of rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 increasing Congo red staining compared to that of the vector control (Fig. 6B). The expression of rcc00645 had no effect (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

Evaluation of R. capsulatus proteins for potential DGC and PDE activities in E. coli. (A) Motility of E. coli MG1655 on semisolid agar (0.25%), which is reduced by DGC activity, when containing the indicated plasmids. (B) Congo red binding by E. coli BL21(DE3), where DGC activity increases fimbria production and Congo red binding, when containing the indicated plasmids. (C) Motility of E. coli MG1655 ΔyhjH on semisolid medium (0.25%), which is increased by PDE activity, when containing the indicated plasmids. In all experiments, transcription of the genes from the plasmid’s lac promoter was induced with IPTG.

We next assessed the effects of the site-directed mutations in the GGDEF and EAL domains in these E. coli DGC assays. The GGAAF mutations in Rcc00620, Rcc02629, and Rcc02857 decreased or abolished their presumed DGC activities in the motility (Fig. S4A) and Congo red binding (Fig. S4B) assays, which is consistent with these three proteins possessing DGC activities in E. coli. The EAL domain mutations did not affect the activities of the Rcc00620 and Rcc02857 proteins (Fig. S4A and B). The GGAAF mutation in Rcc00645 had no effect in either assay, but mutation of the EAL domain resulted in increased DGC activity in both assays (Fig. S4A and B). These results are consistent with Rcc00645 having modest levels of both DGC activity and PDE activity, with the DGC activity only evident when the PDE activity is abolished.

The wild-type and mutant genes were also tested in E. coli MG1655 ΔyhjH, where a drop in intracellular c-di-GMP levels caused by the expression of an active PDE restores swimming motility on semisolid agar (39). Expression of rcc00645, rcc00620, and rcc02857 had little or no observable effect on the swimming phenotype (Fig. 6C). However, the GGAAF mutations in Rcc00620, Rcc00645, and Rcc02857 increased the PDE activities of all three, as indicated by larger swim zones (Fig. S5). Mutation of the EAL domains in these GGAAF mutants reduced or abolished this evidence of PDE activity (Fig. S5). As expected, Rcc02629 did not exhibit PDE activity, nor did its GGAAF mutant version (Fig. S5).

Taken together, these assays indicated that, in E. coli, Rcc02629 acts as a DGC while Rcc00620, Rcc00645, and Rcc02857 possess both DGC and PDE activities.

Effect of aerobic versus anaerobic growth on Rcc00645 and RcGTA production.

The Rcc00645 protein contains several PAS domains, one of which (amino acids [aa] 142 to 244) is predicted to bind heme, a common moiety involved in oxygen sensing. Since both its GGDEF and EAL domains appear to be enzymatically active based on our assays, it is possible that this bifunctional protein switches from acting as a DGC under anaerobic conditions, which were used for the RcGTA production assays, to a PDE under aerobic conditions, which were used for the E. coli motility assays. To test this hypothesis, we assayed GTA production by strain SB645 when grown under aerobic versus anaerobic conditions. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the levels of gene transfer activity in this mutant and the parental strain under aerobic conditions compared to the large increase observed in this strain under anaerobic conditions (Fig. S6). This suggests that oxygen does affect Rcc00645 such that it is more active as a DGC under anaerobic conditions. However, there is no evidence from this result that the protein acts as a PDE under aerobic conditions in R. capsulatus, as gene transfer activity was not lower in the mutant strain (Fig. S6).

c-di-GMP and R. capsulatus flagellar motility.

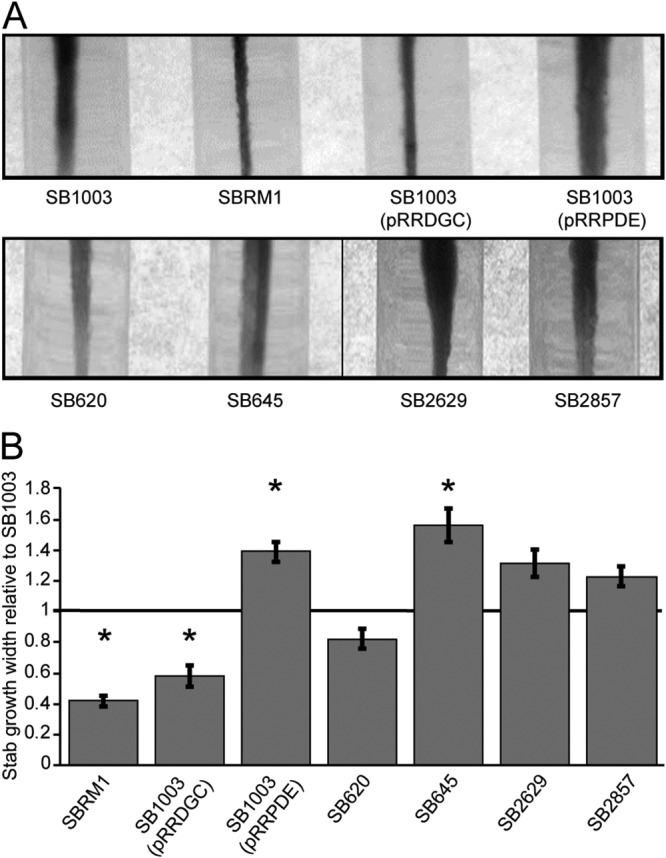

Intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations are commonly involved in regulating flagellar motility in bacteria (23). We therefore conducted flagellar motility assays to look for effects of the gene disruptions and expression of the heterologous PDE and DGC genes on this phenotype in R. capsulatus. The parental strain, SB1003, and its nonmotile ctrA mutant derivative, SBRM1, served as controls. Expression of the heterologous DGC caused a significant decrease in motility, while expression of the heterologous PDE significantly increased the swim diameter (Fig. 7). Therefore, c-di-GMP inhibits flagellar motility in R. capsulatus. With this in mind, the phenotypes of the mutant strains (Fig. 7) were all as predicted based on the results of the experiments presented above (e.g., Fig. 4), although the difference was statistically significant only for SB645.

FIG 7.

Effects of gene disruptions and alterations of c-di-GMP levels on R. capsulatus flagellar motility. (A) Motility assays of the four mutant strains and the parental strain, SB1003, carrying the heterologous PDE and DGC expression plasmids. The parental strain without any manipulation and its nonmotile ctrA null mutant derivative, SBRM1, are included as reference strains. The distance of growth away from the center of the stab lines in 0.35% agar reflects the relative motility of the strain. (B) The swimming diameters from three replicate assays were measured and plotted relative to the value for SB1003. The error bars represent the standard deviations, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to the value for the control, identified using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis, are indicated by asterisks.

DISCUSSION

The genome of R. capsulatus is predicted to encode 2 EAL, 2 GGDEF, and 16 tandem GGDEF/EAL domain-containing proteins (7). Several of these genes were identified in a previous transcriptomic study as having significantly changed transcript levels in the absence of the response regulator CtrA (22), which is absolutely required for the production of RcGTA (9). This led us to hypothesize that these proteins potentially involved in c-di-GMP signaling might affect RcGTA production. Indeed, disruptions of four of the genes were found to affect RcGTA gene transfer activity, as did increasing their copy number, which presumably increased their expression, in the parental strain (Fig. 2; Table 2). Disruptions of rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857 resulted in similar RcGTA phenotypes, with increases in RcGTA production compared to the level in the parental strain, and loss of all three of these genes showed a slightly larger effect than for any one individual gene (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Disruption of rcc00620 lowered RcGTA production compared to the level in the parental strain. Both reporter fusion assays and Western blotting showed that loss of the four genes affected RcGTA gene expression (Fig. 3; Fig. S2). Importantly, increasing the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP by expression of a heterologous DGC inhibited gene transfer activity, while decreasing the c-di-GMP levels by expression of a heterologous PDE stimulated gene transfer activity (Fig. 4; Table 2). The intracellular c-di-GMP levels in the R. capsulatus strains studied matched the expectations based on the phenotypic experiments (Fig. 5), and these results establish that c-di-GMP acts as an inhibitor of RcGTA production and that, with respect to effects on RcGTA, the Rcc00645, Rcc02629, and Rcc02857 proteins act as DGCs in R. capsulatus, whereas Rcc00620 acts as a PDE. Furthermore, c-di-GMP levels and these specific signaling proteins are also implicated in regulating flagellar motility (Fig. 7), further entwining the coregulation of RcGTA production and motility in R. capsulatus (14, 40).

TABLE 2.

Summary of results from R. capsulatus and E. coli assaysa

| Strain or plasmid | R. capsulatus phenotype (RcGTA activity)b |

E. coli strain phenotype |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) fimbria production (Congo red binding)c | MG1655 motilityc | MG1655 ΔyhjH motilityd | ||

| SB620 | ↓ | |||

| SB1003 (p620) | ↑ | |||

| SB645 | ↑ | |||

| SB1003 (p645) | ↓ | |||

| SB2629 | ↑ | |||

| SB1003 (p2629) | ↓ | |||

| SB2857 | ↑ | |||

| SB1003 (p2857) | ↑ | |||

| SB620.645 | = | |||

| SB645.2629.2857 | ↑ | |||

| SB1003 (pRRDGC) | ↓ | |||

| SB1003 (pRRPDE) | ↑ | |||

| pDGC | ↑ | ↓ | = | |

| pPDE | = | = | ↑ | |

| p620 | ↑ | ↓ | = | |

| p620GGAAF | = | = | = | ↑ |

| p620AAL | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | = |

| p620GGAAF/AAL | ↓ | = | = | = |

| p645 | = | = | = | |

| p645GGAAF | ↑ | = | = | ↑ |

| p645AVL | = | ↑ | ↓ | = |

| p645GGAAF/AVL | ↑ | = | = | = |

| p2629 | ↑ | ↓ | = | |

| p2629GGAAF | ↑ | = | = | = |

| p2857 | ↑ | ↓ | = | |

| p2857GGAAF | ↑ | = | = | ↑ |

| p2857ATL | = | ↑ | ↓ | = |

| p2857GGAAF/ATL | ↑ | = | = | = |

Disruptions of the different DGC-encoding genes affect gene transfer to different degrees (Fig. 2A). This could be due to differences in the expression levels of the different genes or enzymatic activities of the encoded proteins or some combination of both these factors. Examination of the transcript levels for these genes (22) from the same growth conditions as used for the experiments here indicated that rcc00645 had the highest transcript levels of the three genes, possibly explaining some of our results. However, the rcc02857 transcript levels were more than 3-fold higher than those of rcc02629, and yet, loss of rcc02629 had a bigger effect on gene transfer activity. Increasing the copy number for all three genes in the wild-type background resulted in similar effects (Fig. 2A), and the c-di-GMP levels in the three different mutants were quite similar (Fig. 5). Therefore, there does not seem to be an easy explanation for the differences in the observed effects for the different genes in terms of transcript levels or magnitudes of effect on intracellular c-di-GMP levels.

Bifunctional DGC-PDE proteins are fairly common (23, 34), and three of the proteins implicated in RcGTA production contain intact versions of both GGDEF and EAL domains, while one contains only a GGDEF domain (Fig. 1). Site-directed mutations in these domains (Fig. 2B) validate the interpretations based on the null mutant (Fig. 2A) and heterologous gene expression (Fig. 4) results. The functionality of these domains and the enzymatic activities of the proteins were further interrogated in E. coli c-di-GMP reporter strain assays. These confirmed that Rcc02629 possesses DGC activity and revealed that the other three proteins display both DGC and PDE activities (Fig. 6 and 7; Table 2; Fig. S4 and S5). As shown by the results from the E. coli assays, for Rcc00620 and Rcc02857, the DGC activity dominates and PDE activity is only evident when the GGDEF domain is mutated, whereas for Rcc00645, the PDE activity dominates and the DGC activity is enhanced by mutation of the EAL domain. These results confirm the functionality of these domains, but determining the activities of the proteins in E. coli and how those results relate to their activities in R. capsulatus needs to take into consideration that the three bifunctional proteins contain additional signaling/regulatory domains that likely regulate their enzymatic activities (37). Indeed, a preliminary investigation of a possible effect of oxygen on the activity of Rcc00645, which contains a PAS domain predicted to bind heme, suggests this bifunctional protein shows higher DGC activity under anaerobic conditions (Fig. S6). It is possible that this differential activity of Rcc00645 with respect to RcGTA is part of the explanation for the observation made more than 40 years ago that much less RcGTA production occurs when cultures are grown aerobically than when they are grown anaerobically (41). Rcc00620 displays DGC activity in E. coli, whereas it acts as a PDE in R. capsulatus. We speculate that the switch between DGC and PDE activities may depend on the phosphorylation status of its N-terminal REC domain (27, 35). The phosphorylation status may differ in R. capsulatus and E. coli due to the lack of cognate kinase/phosphatase protein(s) in E. coli.

How c-di-GMP is connected to RcGTA production mechanistically is unknown at present. One link may involve CckA, the sensor kinase component of the CckA-ChpT-CtrA histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay. This regulatory system has been extensively characterized in C. crescentus (42, 43), where it was also first discovered (20, 44, 45). It is almost universally conserved within the class Alphaproteobacteria (46), although its functions vary among lineages within this group (22, 42, 47–51). Kinase and phosphatase activities of CckA are regulated directly by c-di-GMP in C. crescentus (52, 53). Binding of c-di-GMP by CckA favors phosphatase activity, thus resulting in CtrA existing primarily in the nonphosphorylated state. The C. crescentus CckA c-di-GMP binding sites are conserved in the R. capsulatus protein sequence, suggesting that a similar regulation might also occur in this bacterium, and the effects of disrupting or overexpressing the four genes studied here could therefore be mediated in part by CckA. The dysregulation of these genes in the absence of CtrA, including evidence for direct regulation of rcc00645 by CtrA due to the presence of an upstream consensus binding site (22), would then also suggest there is some sort of feedback loop at work, with these proteins potentially modulating CtrA’s phosphorylation state and CtrA directly and/or indirectly affecting the transcript levels of these genes. A similar feedback situation may also exist in the alphaproteobacterium Dinoroseobacter shibae, where CtrA also affects the transcript levels of c-di-GMP signaling genes (54). Indeed, there are many commonalities in the interconnections of GTA-regulating systems (quorum sensing, LexA, etc.) with other aspects of biology (e.g., flagellar motility) in the two species.

The production and release of RcGTA particles is not as straightforward as once believed. Most of the particle structure is encoded in an approximately 14-kb gene cluster (9), but additional genes essential for the structure (11) and particle release (10) are encoded elsewhere. Genes encoding head spike proteins (12), which are not essential but improve the particles’ binding to recipient cells (11, 12), are also found elsewhere. Importantly, some of these genes, such as the main structural cluster, are transcribed in the presence of unphosphorylated CtrA (14), while others, such as the lysis and head spike genes, require phosphorylated CtrA (CrtA∼P) and are not expressed in the absence of CckA or ChpT (12, 55). It is also important to note that CckA is required for the proper function and release of RcGTA independent of CtrA and CtrA∼P (14), and therefore, if c-di-GMP is affecting CckA activity, some of the effects seen in this study could also be due to this CtrA-independent pathway.

A previous network-based gene coexpression analysis of R. capsulatus microarray transcriptomic data from 23 different strains and/or growth conditions sorted the R. capsulatus genes into 40 distinct modules (56). The rcc00645 gene falls within the same gene module as the RcGTA structural cluster (9), lysis (10), head spike (11, 12), putative tail spike (4, 11), and phage-related regulatory (11, 13) genes. The rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 genes are within a different gene module that also contains the RcGTA-regulatory partner-switching phosphorelay genes, rbaVWY (17). Therefore, in addition to the connections of these c-di-GMP signaling genes with respect to CtrA, RcGTA production, and motility, they show linkages in regulation that are maintained through analysis of diverse transcriptomic data sets.

To the many bacterial processes known to be affected by c-di-GMP signaling (23, 24), this study adds one more, gene transfer. Our experiments show that elevated c-di-GMP concentrations inhibit RcGTA gene transfer and flagellar motility in R. capsulatus. Of the four proteins implicated in affecting RcGTA production and motility, three contain both GGDEF and EAL domains, all of which appear enzymatically functional. Regulation of the activities of these proteins, most likely involving their additional signaling domains (Fig. 1), is therefore expected to be an important aspect of their functioning with respect to these behaviors. Indeed, oxygen appears to be an important factor for the activity of Rcc00645. Additional research is also required to evaluate the possible connection between c-di-GMP signaling uncovered here and the CckA-ChpT-CtrA regulatory pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

All the experimental strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. R. capsulatus was grown either anaerobically under photoheterotrophic conditions in complex YPS medium (57) or aerobically in defined RCV medium (58) at 35°C. Appropriate antibiotics were used when required at the following concentrations: 10 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 3 μg ml−1 gentamicin, 10 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, and 0.5 μg ml−1 tetracycline. E. coli was grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics when necessary at the following concentrations: 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin, 50 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, and 10 μg ml−1 tetracycline.

TABLE 3.

List of bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference(s) and/or source |

|---|---|---|

| R. capsulatus strains | ||

| SB1003 | Genome-sequenced strain | 7, 79 |

| DW5 | SB1003 ΔpuhA | 68 |

| SB346 | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc00346 | This study |

| SB620a | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc00620 | This study |

| SB620 | SB1003 with 1,068-bp deletion in rcc00620 replaced by KIXX | This study |

| SB620.645 | SB620 with 2,469-bp deletion in rcc00645 replaced by gentamycin resistance gene | This study |

| SB645 | SB1003 with 2,469-bp deletion in rcc00645 replaced by KIXX | This study |

| SB645.2629.2857 | SB2629 with 2,469-bp deletion in rcc00645 replaced by gentamycin resistance gene and 909-bp deletion in rcc02857 replaced by spectinomycin resistance gene | This study |

| SB2539 | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc02539 | This study |

| SB2629a | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc02629 | This study |

| SB2629 | SB1003 with 541-bp deletion in rcc02629 replaced by KIXX | This study |

| SB2857a | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc02857 | This study |

| SB2857 | SB1003 with 909-bp deletion in rcc02857 replaced by KIXX | This study |

| SB3177 | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc03177 | This study |

| SB3301 | SB1003 with KIXX insertion in rcc03301 | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| MG1655 | Wild type; motility indicator strain for DGC activity | 80 |

| MG1655 ΔyhjH | Motility indicator strain for PDE activity | 39, 81 |

| BL21(DE3) | Curli fimbria indicator strain for DGC activity | New England Biolabs; 28 |

| C600(pDPT51) | Plasmid-mobilizing strain | 60 |

| S17-1 | Plasmid-mobilizing strain | 67 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | TA PCR product cloning vector | Promega |

| pCM62 | Broad-host-range vector; expression of genes in E. coli driven by lac promoter | 62 |

| pRR5C | Expression of genes in R. capsulatus driven by puf promoter | 64 |

| p620 | rcc00620 and 440 bp of 5′-end sequence in KpnI site of pCM62 | This study |

| p620GGAAF | p620 with mutation in DGC domain | This study |

| p620AAL | p620 with mutation in PDE domain | This study |

| p620GGAAF/AAL | p620 with mutations in both DGC and PDE domains | This study |

| p645 | rcc00645 and 467 bp of 5′-end sequence in KpnI site of pCM62 | This study |

| p645GGAAF | p645 with mutation in DGC domain | This study |

| p645AVL | p645 with mutation in PDE domain | This study |

| p645GGAAF/AVL | p645 with mutations in both DGC and PDE domains | This study |

| p2629 | rcc02629 and 771 bp of 5′-end sequence in KpnI site of pCM62 | This study |

| p2629GGAAF | p2629 with mutation in DGC domain | This study |

| p2857 | rcc02857 and 99 bp of 5′ sequence in KpnI site of pCM62 | This study |

| p2857GGAAF | p2857 with mutation in DGC domain | This study |

| p2857ATL | p2857 with mutation in PDE domain | This study |

| p2857GGAAF/ATL | p2857 with mutations in both DGC and PDE domains | This study |

| pDGC | Heterologous diguanylate cyclase gene from R. sphaeroides (RSP_3513) cloned into pCM62 | This study |

| pRRDGC | Heterologous diguanylate cyclase gene from R. sphaeroides (RSP_3513) cloned into pRR5C | This study |

| pPDE | Heterologous phosphodiesterase gene from G. xylinus (pdeA1) cloned into pCM62 | This study |

| pRRPDE | Heterologous phosphodiesterase gene from G. xylinus (pdeA1) cloned into pRR5C | This study |

| pX3 | RcGTA orfg3′::′lacZ fusion | 10 |

| pX3NP | Promoterless RcGTA orfg3′::′lacZ fusion | 10 |

Insertional mutagenesis, trans complementation plasmids, and site-directed-mutation mutants.

PCR amplifications were done using genomic DNA from R. capsulatus SB1003 as the template and the appropriate primers for each gene (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplified products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Gene disruptions were made by the insertion of the approximately 1.4-kb SmaI fragment of the kanamycin resistance-encoding KIXX fragment (59) at specific restriction enzyme cut sites within the cloned PCR products, as detailed below.

The rcc00346 open reading frame (ORF) was disrupted at the BsaBI site 319 bp from the start of the 1,545-bp ORF, rcc00620 at the EcoRI site 793 bp from the start of the 1,833-bp ORF, rcc00645 at the ClaI site 83 bp from the start of the 3,738-bp ORF (there is also a second ClaI site in this ORF, which results in a 2,469-bp deletion), rcc02539 at the StuI site 469 bp from the start of the 1,926-bp ORF, rcc02540 at the HindIII site 300 bp from the start of the 2,757-bp ORF, rcc02629 at the MscI site 517 bp from the start of the 1,062-bp ORF, rcc02857 at the BamHI site 422 bp from the start of the 3,477-bp ORF, rcc03177 at the BstEII site 102 bp from the start of the 843-bp ORF, and rcc03301 at the StuI site 526 bp from the start of the 3,855-bp ORF. Gene disruptions were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestions and conjugated to R. capsulatus from E. coli C600 (pDPT51) (60). RcGTA transfer of the disrupted genes into the chromosome of recipient strain SB1003 cells was then performed to generate R. capsulatus mutant strains (61). The resulting kanamycin-resistant strains were confirmed to contain only the disrupted versions of the genes by PCR using the original amplification primers.

Deletion mutants with mutations of the rcc00620, rcc02629, and rcc02857 genes were subsequently made by replacing portions of the ORFs with the KIXX fragment. For rcc00620, 1,068 bp were deleted between two AvaI sites (deletion starts 144 bp into the ORF). For rcc02629, 541 bp were deleted between two BamHI sites (deletion starts 8 bp into the ORF). For rcc02857, 909 bp were deleted between two BsaBI sites (deletion starts 2,296 bp into the ORF). Chromosomal disruptions and subsequent confirmations were done as described above. For rcc00645, 2,469 bp was already deleted between two ClaI sites when the original disruption was made. In addition to these individual mutants with KIXX insertions, additional mutants were made for rcc00645 and rcc002857 using different antibiotic resistance genes. A gentamicin resistance gene was inserted at the ClaI deletion site for rcc00645 and a spectinomycin resistance gene was inserted into rcc002857 at the BsaBI deletion site. These constructs were used to create double (rcc00620 and rcc00645) and triple (rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857) mutants by RcGTA transfer into the chromosome of the appropriate recipient mutant strains, as described above.

trans complementation constructs were made using the pCM62 plasmid (62) as a vector. The structural genes and their upstream regulatory regions were amplified using gene-specific complementation primers (Table S1). The amplified fragments were cloned into pCM62 as KpnI fragments. The four knockout strains containing the empty plasmid were subsequently used as the reference strains.

To alter the c-di-GMP levels in R. capsulatus cells, plasmids carrying genes from other bacteria with known DGC (dgcA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides) (27) and PDE (pdeA1 from Gluconacetobacter xylinus) (63) activities were constructed. The dgcA and pdeA1 genes were amplified using gene-specific primers (Table S1) and cloned into pRR5C (64), which leads to transcription in R. capsulatus under the control of the puf promoter. These genes were also cloned into pCM62 (62) to allow transcription in E. coli from the lac promoter.

To create point mutations in the predicted DGC and PDE domains, site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the pCM62-based clones described above were used as templates for PCR with PfuUltra high-fidelity DNA polymerase and gene-specific primers (Table S1) designed to change the critical residues of the GGDEF (GGDEF to GGAAF) and EAL (EAL, EVL, and ETL to AAL, AVL, and ATL, respectively) domains. These substitutions were chosen as they were previously shown to disrupt the function of these domains (65, 66). The methylated template DNA was then digested by incubation with DpnI for 10 min at 37°C, and the remaining DNA was transformed into E. coli cells. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing. These pCM62 constructs allow the genes to be transcribed from their native upstream sequences in R. capsulatus and from the plasmid’s lac promoter in E. coli.

Plasmids were conjugated into R. capsulatus using E. coli strain S-17 (67).

Gene transfer bioassays.

RcGTA-mediated gene transfer activity was measured as described previously (61), with quantification of the transfer of an essential photosynthesis gene, puhA, to a ΔpuhA mutant strain, DW5 (68). Aerobically grown overnight cultures of test strains were normalized for density and used to inoculate anaerobic phototrophic cultures. These cultures were grown for approximately 48 h and filtered using 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) syringe filters, and filtrates were assayed for RcGTA gene transfer activity. RcGTA activities of the mutant strains were measured as ratios relative to the activity of the parental strain SB1003 in at least three replicate experiments. For assaying the RcGTA production under aerobic conditions, the GTA donor cultures (SB1003 and SB645) were grown aerobically (with shaking at 220 rpm) for approximately 48 h at 35°C and then assayed for RcGTA gene transfer activity as described above. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc analysis in R (69) was used to identify statistically significant differences in RcGTA activities.

Quantification of c-di-GMP.

The quantification of c-di-GMP levels in cells was done using a protocol adapted from reference 70. Aerobically grown overnight cultures of the different R. capsulatus strains were normalized for cell density and used to inoculate anaerobic photoheterotrophic cultures. These cultures were grown for approximately 48 h, 3 ml of each culture was removed, and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellet was then resuspended in 100 μl ice-cold PBS and incubated at 100°C for 5 min. Ice-cold 100% ethanol (186 μl; final concentration, 65%) was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 15 s, followed by centrifugation at 4°C. The supernatant containing the extracted c-di-GMP was then collected and transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. This extraction procedure was repeated twice more for each cell pellet, and the supernatants were pooled into a single tube. The pellets were saved for protein quantification. The combined supernatants were dried in a centrifugal evaporator at 30°C for 4 to 5 h. The resulting dried extracts were resuspended in 100 μl ultrapure water, briefly vortexed, and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were then transferred to 250-μl glass microinserts which were placed into high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) vials for analysis. Cyclic di-GMP was detected using a Hewlett Packard 1050 HPLC system consisting of an autosampler, a quaternary pump, and a multiple-wavelength detector (Agilent Technologies). HPLC was performed with mobile phase parts A (10 mM ammonium acetate in H2O) and B (10 mM ammonium acetate in methanol), with elution using a gradient from 5% B for the first 6 min to 15% B at 11 min, 25% B at 25 min, and 90% B at 17 min and a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. The backpressure of the system was 1 × 107 ± 5 × 105 Pa. The injection volume was 20 μl, and detection was at 253 nm. The run time was 19 min with a post time of 11 min, and the retention time of c-di-GMP was 13.0 ± 0.1 min. ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies) was used to control the instrument and collect the data. Analytical separations were performed using a Luna column (3 μm, C18, 100 by 4.6 mm; Phenomonex). A standard curve was made using solutions of c-di-GMP (Biolog) in H2O (80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0 μg liter−1). Standards were measured from triplicate injections. Culture samples were prepared in triplicate, and each replicate was quantified from triplicate injections.

For protein quantification, the cell pellets from the c-di-GMP extractions were resuspended by adding 500 μl Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and sonicated on ice for a total of 2 min using 20-s bursts. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (71). Briefly, 60 μl of 10-fold-diluted sample in TE buffer was added to a polystyrene cuvette containing 3 ml of Bradford reagent (0.005% [wt/vol] Coomassie brilliant blue G-250, 8.5% [wt/vol] H3PO4). The mixture was incubated for 5 min, and the absorbance at 595 nm was measured. A standard curve was constructed using bovine serum albumin solution standards (25, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 1,000 μg ml−1). The concentration of c-di-GMP was then normalized to protein levels in the cells. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis in R was used to identify statistically significant differences in c-di-GMP levels.

Western blotting.

Western blotting to detect the RcGTA major capsid protein (approximately 32 kDa) was carried out to quantify RcGTA protein levels within cells and released into the extracellular environment. This was performed on the same cultures that were used for gene transfer assays, as described previously (14). Briefly, 0.5 ml of each culture was centrifuged at >14,000 × g and a 0.2-ml sample was collected from the supernatant. The remaining supernatant was carefully removed from the cell pellet, and 0.5 ml of TE buffer was added to resuspend the cells. Samples for SDS-PAGE were prepared by mixing 5 μl of cells and 10 μl of supernatant with SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer (NEB) and heating at 98°C for 5 min. Ten percent SDS-PAGE gels were used to separate the proteins, followed by transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting in transfer buffer (48 mM Tris base, 39 mM glycine, 20% methanol [vol/vol]). The membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk solution in TBST (20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 [vol/vol], pH 7.5) and incubated with the primary antibody, anti-Rhodobacterales GTA major capsid protein antibody (Agrisera) (72), overnight at 4°C. After a washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody, peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), at room temperature for 1 h. The SuperSignal west femto reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to detect the bands by chemiluminescence, and images were captured using an Agilent ImageQuant LAS 4000 imaging system. Images were inverted and adjusted for brightness and contrast, and band intensities were quantified using ImageJ (73).

β-Galactosidase assays.

A plasmid carrying an in-frame fusion of orfg3 of the RcGTA structural gene cluster, along with upstream sequences including the cluster’s promoter region, to lacZ (10) was used to quantify RcGTA gene expression. A version lacking the promoter region was used as a negative control. The R. capsulatus strains were grown under the same conditions and for the same time as for RcGTA gene transfer activity assays and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described previously (74). Briefly, the cell density of each culture was measured via absorbance at 600 nm and 0.1 ml of each was centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4 ⋅ 7H2O, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4 ⋅ 7H2O, 10 mM KCl, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7). The cells were permeabilized by adding two drops of chloroform and one drop of 0.1% SDS, followed by incubation at 28°C for 5 min. ortho-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside was added (0.67 mg ml−1 final concentration), the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature until visible yellow color developed, and then the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5 ml 1 M Na2CO3. Cell material was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatants were measured for absorbance at 420 nm. β-Galactosidase activities were calculated in Miller units (74).

Bioinformatic analyses.

Protein sequence analyses, for identification of functional domains, were done using the SMART (75, 76) and Expasy-Prosite (77) databases. Sequence alignments were done using Clustal Omega (78).

E. coli motility assays.

Swimming assays using E. coli MG1655 and E. coli MG1655 ΔyhjH to detect DGC and PDE activities, respectively, were performed as described previously (38). The pCM62-based clones of rcc00620, rcc00645, rcc02629, and rcc02857 genes, their respective site-directed mutants, and controls (dgcA from R. sphaeroides and pdeA1 from G. xylinus) were transformed into the E. coli strains. Five-microliter amounts of overnight cultures were inoculated onto semisolid (0.25% agar) LB plates containing 0.25 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and 0.5% NaCl, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 to 6 h and photographed. The images were manipulated for brightness and contrast to help improve the visibility of the bacterial growth zones.

In-cell DGC activity assays.

The same pCM62-based plasmids used for motility assays were also transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) to perform Congo red binding assays as described previously (38). Briefly, 3-μl amounts from overnight cultures of all the strains were streaked on LB agar containing 25 μg ml−1 Congo red and 0.1 mM IPTG, and the plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h and photographed.

R. capsulatus motility assays.

Aerobically grown overnight cultures were used to inoculate YPS agar (0.35%) stabs in test tubes that were incubated at 35°C under phototrophic conditions for 16 to 24 h. The tubes were photographed, and the diameters of the zones of growth were measured using ImageJ. The stab motility assays were performed in three independent growth experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis in R was used to identify statistically significant differences in the measured stab swim zones.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Buckley for work on construction of some of the initial strains investigated.

This research was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada to A.S.L. (grant numbers RGPIN-2012-341561 and RGPIN-2017-04636) and L.P.-C. (grant number RGPIN-2011-402087). P.P. was supported by funding from Memorial University’s School of Graduate Studies.

P.P., A.S.L., and M.G. conceived the study, and P.P. and E.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. P.P., L.P.-C., M.G., and A.S.L. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raz Y, Tannenbaum E. 2010. The influence of horizontal gene transfer on the mean fitness of unicellular populations in static environments. Genetics 185:327–337. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang AS, Beatty JT. 2007. Importance of widespread gene transfer agent genes in α-proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol 15:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanton TB. 2007. Prophage-like gene transfer agents—novel mechanisms of gene exchange for Methanococcus, Desulfovibrio, Brachyspira, and Rhodobacter species. Anaerobe 13:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang AS, Westbye AB, Beatty JT. 2017. The distribution, evolution, and roles of gene transfer agents in prokaryotic genetic exchange. Annu Rev Virol 4:87–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-101416-041624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomasch J, Wang H, Hall ATK, Patzelt D, Preusse M, Petersen J, Brinkmann H, Bunk B, Bhuju S, Jarek M, Geffers R, Lang AS, Wagner-Döbler I. 2018. Packaging of Dinoroseobacter shibae DNA into gene transfer agent particles is not random. Genome Biol Evol 10:359–369. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrs B. 1974. Genetic recombination in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 71:971–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strnad H, Lapidus A, Paces J, Ulbrich P, Vlcek C, Paces V, Haselkorn R. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the photosynthetic purple nonsulfur bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus SB1003. J Bacteriol 192:3545–3546. doi: 10.1128/JB.00366-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yen HC, Hu NT, Marrs BL. 1979. Characterization of the gene transfer agent made by an overproducer mutant of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Mol Biol 131:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang AS, Beatty JT. 2000. Genetic analysis of a bacterial genetic exchange element: the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:859–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hynes AP, Mercer RG, Watton DE, Buckley CB, Lang AS. 2012. DNA packaging bias and differential expression of gene transfer agent genes within a population during production and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent, RcGTA. Mol Microbiol 85:314–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes AP, Shakya M, Mercer RG, Grüll MP, Bown L, Davidson F, Steffen E, Matchem H, Peach ME, Berger T, Grebe K, Zhaxybayeva O, Lang AS. 2016. Functional and evolutionary characterization of a gene transfer agent’s multilocus “genome.” Mol Biol Evol 33:2530–2543. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westbye AB, Kuchinski K, Yip CK, Beatty JT. 2016. The gene transfer agent RcGTA contains head spikes needed for binding to the Rhodobacter capsulatus polysaccharide cell capsule. J Mol Biol 428:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogg P. 2019. Identification and characterization of a direct activator of a gene transfer agent. Nat Commun 10:595. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer RG, Quinlan M, Rose AR, Noll S, Beatty JT, Lang AS. 2012. Regulatory systems controlling motility and gene transfer agent production and release in Rhodobacter capsulatus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 331:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer AL, Taylor TA, Beatty JT, Greenberg EP. 2002. Long-chain acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing regulation of Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent production. J Bacteriol 184:6515–6521. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.23.6515-6521.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung MM, Brimacombe CA, Spiegelman GB, Beatty JT. 2012. The GtaR protein negatively regulates transcription of the gtaRI operon and modulates gene transfer agent (RcGTA) expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol 83:759–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercer RG, Lang AS. 2014. Identification of a predicted partner-switching system that affects production of the gene transfer agent RcGTA and stationary phase viability in Rhodobacter capsulatus. BMC Microbiol 14:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchinski KS, Brimacombe CA, Westbye AB, Ding H, Beatty TJ. 2016. The SOS response master regulator LexA regulates the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus and represses transcription of the signal transduction protein CckA. J Bacteriol 198:1137–1148. doi: 10.1128/JB.00839-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westbye AB, Kater L, Wiesmann C, Ding H, Yip CK, Beatty JT. 2018. The protease ClpXP and the PAS-domain protein DivL regulate CtrA and gene transfer agent production in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00275-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00275-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quon KC, Marczynski GT, Shapiro L. 1996. Cell cycle control by an essential bacterial two-component signal transduction protein. Cell 84:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80995-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skerker JM, Laub MT. 2004. Cell-cycle progression and the generation of asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:325–337. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer RG, Callister SJ, Lipton MS, Pasa-Tolic L, Strnad H, Paces V, Beatty JT, Lang AS. 2010. Loss of the response regulator CtrA causes pleiotropic effects on gene expression but does not affect growth phase regulation in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol 192:2701–2710. doi: 10.1128/JB.00160-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenal U, Reinders A, Lori C. 2017. Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:271–284. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev 18:715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan C, Paul R, Samoray D, Amiot NC, Giese B, Jenal U, Schirmer T. 2004. Structural basis of activity and allosteric control of diguanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:17084–17089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol 187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christen B, Christen M, Paul R, Schmid F, Folcher M, Jenoe P, Meuwly M, Jenal U. 2006. Allosteric control of cyclic di-GMP signaling. J Biol Chem 281:32015–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schirmer T, Jenal U. 2009. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol 187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christen M, Christen B, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. 2005. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J Biol Chem 280:30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2005. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem 280:33324–33330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Crossman LC, Spiro S, He Y-W, Zhang L-H, Heeb S, Camara M, Williams P, Dow JM. 2006. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:6712–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Tarutina M, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. 2006. An unorthodox bacteriophytochrome from Rhodobacter sphaeroides involved in turnover of the second messenger c-di-GMP. J Biol Chem 281:34751–34758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levet-Paulo M, Lazzaroni JC, Gilbert C, Atlan D, Doublet P, Vianney A. 2011. The atypical two-component sensor kinase Lpl0330 from Legionella pneumophila controls the bifunctional diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase Lpl0329 to modulate bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP synthesis. J Biol Chem 286:31136–31144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi Y, Chuah MLC, Dong X, Xie K, Luo Z, Tang K, Liang Z-X. 2011. Binding of cyclic diguanylate in the non-catalytic EAL domain of FimX induces a long-range conformational change. J Biol Chem 286:2910–2917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfe AJ, Visick KL (ed). 2010. The second messenger cyclic di-GMP. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen L-H, Köseoğlu VK, Güvener ZT, Myers-Morales T, Reed JM, D’Orazio SEF, Miller KW, Gomelsky M. 2014. Cyclic di-GMP-dependent signaling pathways in the pathogenic firmicute Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004301. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Römling U, Gomelsky M. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP. J Biol Chem 281:30310–30314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang AS, Beatty JT. 2002. A bacterial signal transduction system controls genetic exchange and motility. J Bacteriol 184:913–918. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.913-918.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solioz M. 1975. The gene transfer agent of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. PhD Thesis. Saint Louis University, St Louis, MO.

- 42.Curtis PD, Brun YV. 2010. Getting in the loop: regulation of development in Caulobacter crescentus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:13–41. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsokos CG, Laub MT. 2012. Polarity and cell fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Curr Opin Microbiol 15:744–750. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs C, Domian IJ, Maddock JR, Shapiro L. 1999. Cell cycle-dependent polar localization of an essential bacterial histidine kinase that controls DNA replication and cell division. Cell 97:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biondi EG, Reisinger SJ, Skerker JM, Arif M, Perchuk BS, Ryan KR, Laub MT. 2006. Regulation of the bacterial cell cycle by an integrated genetic circuit. Nature 444:899–904. doi: 10.1038/nature05321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brilli M, Fondi M, Fani R, Mengoni A, Ferri L, Bazzicalupo M, Biondi EG. 2010. The diversity and evolution of cell cycle regulation in alpha-proteobacteria: a comparative genomic analysis. BMC Syst Biol 4:52. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnett MJ, Hung DY, Reisenauer A, Shapiro L, Long SR. 2001. A homolog of the CtrA cell cycle regulator is present and essential in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 183:3204–3210. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3204-3210.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellefontaine A-F, Pierreux CE, Mertens P, Vandenhaute J, Letesson J-J, De Bolle X. 2002. Plasticity of a transcriptional regulation network among alpha-proteobacteria is supported by the identification of CtrA targets in Brucella abortus. Mol Microbiol 43:945–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J, Heindl JE, Fuqua C. 2013. Coordination of division and development influences complex multicellular behavior in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. PLoS One 8:e56682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greene SE, Brilli M, Biondi EG, Komeili A. 2012. Analysis of the CtrA pathway in Magnetospirillum reveals an ancestral role in motility in alphaproteobacteria. J Bacteriol 194:2973–2986. doi: 10.1128/JB.00170-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller TR, Belas R. 2006. Motility is involved in Silicibacter sp. TM1040 interaction with dinoflagellates. Environ Microbiol 8:1648–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mann TH, Seth Childers W, Blair JA, Eckart MR, Shapiro L. 2016. A cell cycle kinase with tandem sensory PAS domains integrates cell fate cues. Nat Commun 7:11454. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lori C, Ozaki S, Steiner S, Böhm R, Abel S, Dubey BN, Schirmer T, Hiller S, Jenal U. 2015. Cyclic di-GMP acts as a cell cycle oscillator to drive chromosome replication. Nature 523:236–239. doi: 10.1038/nature14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koppenhöfer S, Wang H, Scharfe M, Kaever V, Wagner-Döbler I, Tomasch J. 2019. Integrated transcriptional regulatory network of quorum sensing, replication control, and SOS response in Dinoroseobacter shibae. Front Microbiol 10:803. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Westbye AB, Leung MM, Florizone SM, Taylor TA, Johnson JA, Fogg PC, Beatty JT. 2013. Phosphate concentration and the putative sensor kinase protein CckA modulate cell lysis and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent. J Bacteriol 195:5025–5040. doi: 10.1128/JB.00669-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peña-Castillo L, Mercer RG, Gurinovich A, Callister SJ, Wright AT, Westbye AB, Beatty JT, Lang AS. 2014. Gene co-expression network analysis in Rhodobacter capsulatus and application to comparative expression analysis of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. BMC Genomics 15:730. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wall JD, Weaver PF, Gest H. 1975. Gene transfer agents, bacteriophages, and bacteriocins of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Arch Microbiol 105:217–224. doi: 10.1007/bf00447140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beatty JT, Gest H. 1981. Generation of succinyl-coenzyme A in photosynthetic bacteria. Arch Microbiol 129:335–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00406457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barany F. 1985. Single-stranded hexameric linkers: a system for in-phase insertion mutagenesis and protein engineering. Gene 37:111–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor DP, Cohen SN, Clark WG, Marrs BL. 1983. Alignment of genetic and restriction maps of the photosynthesis region of the Rhodopseudomonas capsulata chromosome by a conjugation-mediated marker rescue technique. J Bacteriol 154:580–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hynes AP, Lang AS. 2013. Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent (RcGTA) activity bioassays. Bio Protoc 3:e317. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065–2075. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang AL, Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Mayer R, Weinhouse H, Volman G, Amikam D, Benziman M, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. 2001. Phosphodiesterase A1, a regulator of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum, is a heme-based sensor. Biochemistry 40:3420–3426. doi: 10.1021/bi0100236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young CS, Reyes RC, Beatty JT. 1998. Genetic complementation and kinetic analyses of Rhodobacter capsulatus ORF1696 mutants indicate that the ORF1696 protein enhances assembly of the light-harvesting I complex. J Bacteriol 180:1759–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newell PD, Yoshioka S, Hvorecny KL, Monds RD, O’Toole GA. 2011. Systematic analysis of diguanylate cyclases that promote biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. J Bacteriol 193:4685–4698. doi: 10.1128/JB.05483-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuchma SL, Brothers KM, Merritt JH, Liberati NT, Ausubel FM, O’Toole GA. 2007. BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J Bacteriol 189:8165–8178. doi: 10.1128/JB.00586-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong DKH, Collins WJ, Harmer A, Lilburn TG, Beatty JT. 1996. Directed mutagenesis of the Rhodobacter capsulatus puhA gene and Orf 214: pleiotropic effects on photosynthetic reaction center and light-harvesting 1 complexes. J Bacteriol 178:2334–2342. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2334-2342.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hesterberg T, Chambers JM, Hastie TJ. 1993. Statistical models in S. Technometrics 35:227–228. doi: 10.2307/1269676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roy A, Petrova O, Sauer K. 2016. Extraction and quantification of cyclic di-GMP from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bio Protoc 3:e828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He F. 2016. Bradford protein assay. Bio Protoc 1:e45. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fu Y, MacLeod DM, Rivkin RB, Chen F, Buchan A, Lang AS. 2010. High diversity of Rhodobacterales in the subarctic North Atlantic ocean and gene transfer agent protein expression in isolated strains. Aquat Microb Ecol 59:283–293. doi: 10.3354/ame01398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Letunic I, Copley RR, Schmidt S, Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, Schultz J, Ponting CP, Bork P. 2004. SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D142–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. 1998. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Castro E, Sigrist CJA, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Hulo N. 2006. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W362–W365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yen HC, Marrs B. 1976. Map of genes for carotenoid and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Bacteriol 126:619–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blattner FR, Plunkett G III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Simm R, Morr M, Kader A, Nimtz M, Römling U. 2004. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol Microbiol 53:1123–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.