Abstract

Retinol binding protein IV (RBP) functions as the principal carrier of retinol (Vitamin A) in the blood, where RBP circulates bound to another serum protein, transthyretin. Isolation of pure RBP from the transthyretin complex in human serum can be difficult, but expression of RBP in recombinant systems can circumvent these purification issues. Human recombinant RBP has previously been successfully expressed and purified from E. coli, but recovery of active protein typically requires extensive processing steps, such as denaturing and refolding, and complex purification steps, such as multi-modal chromatography. Furthermore, these methods produce recombinant proteins, often tagged, that display different functional and structural characteristics across systems. In this work, we optimized downstream processing by use of an intein-based expression system in E. coli to produce tag-free, human recombinant RBP (rRBP) with intact native amino termini at yields of up to ~15 mg/L off column. The novel method requires solubilization of inclusion bodies and subsequent oxidative refolding in the presence of retinol, but importantly allows for one-step chromatographic purification that yields high purity rRBP with no N-terminal Met or other tag. Previously reported purification methods typically require two or more chromatographic separation steps to recover tag-free rRBP. Given the interest in mechanistic understanding of RBP transport of retinol in health and disease, we characterized our purified product extensively to confirm rRBP is both structurally and functionally a suitable replacement for serum-derived RBP.

Keywords: Retinol Binding Protein, Inteins, Oxidative Refolding, Transthyretin, Retinol

Introduction

Human retinol binding protein IV (RBP) is a non-glycosylated, 21 kDa protein belonging to the lipocalin family [1]. RBP consists of a single polypeptide chain of 183 residues that forms a β-barrel secondary structure motif constrained by three disulfide bonds [2]. Retinol (ROH) binds within the calyx where it is nearly completely shielded from the aqueous environment [1]. The crystallographic structure (PDB Entry 5NU7) for human RBP is shown in Figure 1 [3].

Figure 1:

PDB Entry 5NU7. X-ray structure of serum RBP with bound retinol (ROH). Both ROH and RBP tryptophans are shown in black.

In vivo, RBP is synthesized ligand free (apo) in the liver and loaded with retinol to form the ROH-RBP (holo) complex. In the bloodstream, holo-RBP circulates bound to a 55 kDa protein, transthyretin (TTR), to form a 76 kDa three-body complex. It is hypothesized that formation of the RBP-TTR complex serves to prevent loss of retinol via kidney filtration [4].

RBP is produced in other tissues as well, including adipocytes [5] and the choroid plexus [6]. Serum RPB levels are elevated in obesity, which has been linked to the onset of insulin resistance [7]; in the cerebrospinal fluid, both RBP and TTR concentrations are higher in Alzheimer’s disease patients when compared to controls [6]. Fundamental research into the connection between RBP and these chronic diseases would be greatly facilitated by the ready availability of correctly folded and functional purified protein. However, recovery of holo-RBP from the serum is difficult, because most holo-RBP is complexed to TTR in the blood and co-elutes in chromatographic separations. Disruption of the TTR-RBP interaction, followed by additional chromatographic steps, is necessary to purify holo-RBP from TTR, and the yield is relatively low [8]. Apo-RBP is even more difficult to isolate, as it cannot be identified by retinol absorbance and its concentration is low.

Recombinant RBP (rRBP) production is attractive because yields can be significantly higher, and chromatographic purification can be simpler. To date, the protein has been successfully expressed and purified in E. coli by several different groups (Table 1) [9–13]. However, in none of these cases was rRBP produced in good yield without N-terminal or C-terminal modifications from the native human sequence. Additionally, since inclusion bodies were produced during expression, refolding and additional purification steps were needed in order to recover biologically active protein. More recently, one group reported rRBP expression in soluble form in Pichia pastoris [13], avoiding refolding, but purification required an N-terminal His tag which was not removed. Recovery of apo-rRBP is typically obtained by stripping ROH from holo-rRBP with an organic solvent, but little data is available on whether stripping affects RBP integrity. Finally, biophysical characterization of the rRBP product has not always been thorough, leading to concerns about the quality and performance of the recombinant protein in mechanistic studies, such as measuring release of retinol to target tissues [14].

Table 1:

Literature summary on recombinant RBP Production

| Reference | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | [13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Organism | E. Coli | E. Coli | E. Coli | E. Coli | Pichia pastoris |

| RBP Sequence | Porcine | Human | Human | Human | Human |

| Native Sequence Modification | C-Terminal His-Tag | None | N-terminal Met | N-terminal Met | N-Terminal His-Tag |

| Expression Target | Soluble apo-protein into periplasm | Soluble apo-protein into periplasm | Insoluble inclusion bodies | Insoluble inclusion bodies | Secreted into medium |

| Other Comments | Required co-expression of PDI and PPI | Retinol added prior to purification | Solubilized with 8M urea | Solubilized with 5 M GdmHCl/10 mM DTT | None |

| Refolding Process | None | None | Dialysis versus diethanolamine buffer | Rapid dilution and mixing in oxidative buffer with retinol | None |

| Purification Scheme | Metal Chelate Affinity | TTR Affinity | Anion Exchange followed by Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis | Anion Exchange | Metal Chelate Affinity |

| Yield | ∼ 0.15 mg/L | ∼ 0.2 mg/L | ∼ 20 mg/L | ∼ 70 mg/L | ∼ 5 mg/L |

| Final product | Apo-protein | Holo-protein | Apo-protein | Holo-protein | Apo-protein |

In this report, we demonstrate expression of rRBP as a fusion protein with an N-terminal intein tag that is removed by self-cleavage during purification. This method has been used successfully by our group to produce other proteins in E. coli [15, 16]; for RBP, this system produces a protein with fully native human sequence. Inclusion bodies are denatured and refolded in an oxidative environment in the presence of retinol prior to one-step chromatographic purification. A method for stripping retinol from holo-rRBP was demonstrated that does not affect rRBP quality upon reconstitution with fresh retinol. Purified rRBP, in both holo and apo forms, was characterized by multiple biophysical assays for comparison to data of human RBP purified from serum when possible, or to other recombinant systems if no serum data was available. To our knowledge, this constitutes the most extensive characterization of human rRBP to date.

Materials and Methods

rRBP expression, refolding and purification

All materials were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific unless stated otherwise. The human RBP IV gene without the signaling peptide (UniProt KB P02753) was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli using Genscript’s OptimumGene algorithm. The gene was synthesized using the Nrul and BamHI restriction sites at the 5’ and 3’ positions, respectively, and ligated into the pTWIN1 plasmid (New England Biolabs). This plasmid allows for generation of a fusion construct containing an intein tag and a high affinity chitin binding domain that is governed under a T7 promoter system. The intein can undergo self-cleavage at room temperature and low pH to release the desired protein at high purity. BL21-DE3 cells (New England Biolabs) were transformed with ligated plasmid and cultured in 500 mL of LB media [17] containing 100 mg/L ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG (IBI Scientific) to a final concentration of 750 μM during mid-log-phase growth as determined by OD600 (0.6 – 0.8). After 4 hours at 37° C, the bacteria were harvested, pelleted, pooled and re-suspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM PMSF solubilized in isopropanol, pH 9.0). Cells were lysed by sonication for 45 minutes in an ice bath. The lysate was centrifuged at 4000 RPM in a swinging bucket rotor for 30 minutes at 4° C. rRBP was primarily expressed in the inclusion body pellet. The pellet was re-suspended in 25 mL of breaking buffer, prepared by dilution of 8 M guanidine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) into solubilizing buffer (25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0, supplemented with 10 mM DTT and 2 mM PMSF) to a final guanidine hydrochloride (GdmHCl) concentration of 5 M; the protein solution was stirred vigorously overnight to ensure complete reduction and denaturation of the protein.

The next day, excess cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 4000 RPM for 45 minutes at 4° C, and the supernatant was collected and diluted 1:4 v/v with cold refolding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.3 mM cystine (Sigma- Aldrich), 0.5 mg fresh synthetic retinol (95%, Sigma-Aldrich) in ethanol (Koptec), pH 9.0) for a final GdmHCl concentration of 1 M. To ensure optimal folding, the retinol was added to the vigorously stirring refolding buffer immediately prior to addition of the reduced and denatured rRBP. Because retinol is highly sensitive to light, the column and solutions containing retinol were covered in aluminum foil. rRBP was allowed to refold while stirring vigorously at 4° C for 5 hours, upon which the solution was immediately applied to a chitin affinity column (New England Biolabs) equilibrated at 4° C with refolding buffer containing GdmHCl at an identical final concentration as the rRBP solution. The column was thoroughly washed with wash buffer (25 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0) to remove GdmHCl, adsorbed cellular protein contaminants and unbound retinol. The column was then equilibrated with elution buffer (25 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, pH 6.5) and incubated at room temperature overnight to initiate cleavage of the intein. ROH-rRBP (rRBP bound to retinol) was eluted from the column and the retinol content checked by an absorbance scan from 260 nm - 380 nm.

Anion exchange (AEX) chromatography

ROH-rRBP eluted from the chitin column was concentrated and buffer exchanged into AEX Buffer A (25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) in a 10 kDa Amicon-15 MWCO regenerated cellulose membrane filter (MilliporeSigma). The retentate was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (Millipore) and slowly applied by syringe to a GE HiScreen diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) column pre-equilibrated with AEX Buffer A. The sample was allowed to adsorb for 10 minutes without flow. The column was then re-equilibrated for 10 minutes with AEX Buffer A at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. A step salt gradient was applied by mixing AEX Buffer A with high salt AEX Buffer B (25 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at an 80:20 % v/v ratio. This solution was applied to the DEAE column at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min to elute the protein. The column was then stripped for 20 minutes at 1.0 mL/min with 100 % AEX Buffer B before subsequent runs.

Retinol stripping

ROH-rRBP was chilled to 4° C then stripped of retinol by 1:1 v/v dilution in chilled diethyl ether with gentle rocking overnight at 4° C. The organic phase was carefully removed without disturbing the organic/aqueous interface and replaced with fresh, cold diethyl ether prior to rocking for an additional 3 hours. The aqueous phase, containing apo-rRBP, was then slowly removed with a syringe and placed under nitrogen at room temperature to evaporate trace diethyl ether. Apo-rRBP was concentrated and buffer exchanged to PBS (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) by ultrafiltration at 4° C with a 10 kDa Amicon membrane filter centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes. To reduce aggregation during the centrifugation process, the apo-rRBP concentrations were kept near 0.25 mg/mL. The retentate was then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter (MilliporeSigma) to remove any large aggregates and quantified via absorbance at 280 nm on an Eppendorf BioSpectrometer using an extinction coefficient (ε280) of 40,400 M−1 cm−1 [18].

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis

Samples were diluted by addition of 2X Novex Tricine SDS Sample Buffer and boiled at 85° C for two minutes. The denatured protein was loaded alongside an EZ-Run Protein Ladder (Fisher BioReagents, Fair Lawn, NJ) on a Novex 10 – 20 % Tricine gradient gel and electrophoresed using Novex Tricine SDS Running Buffer for 90 minutes at 125 V. The gel was then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and analyzed with a Bio Rad ChemiDoc imaging system.

Preparation of holo-rRBP from apo-rRBP

Holo-rRBP was prepared by dilution of fresh, concentrated retinol (ROH) or retinoic acid (RA) at a 3-fold molar excess in ice cold ethanol into 10 μM apo-rRBP. The concentration of ligand in ethanol was calculated by using an extinction coefficient (ε325) of 52,480 M−1 cm−1 and (ε350) of 44,300 M−1 cm−1 for ROH and RA, respectively. The final ethanol concentration was kept < 1 % v/v in the protein sample. The mixture was equilibrated for 24 hours at 4° C to ensure ligand binding. Since serum holo-RBP demonstrates ligand to protein absorbance ratios of ~ 1.0 [19–21], confirmation of binding was determined by an absorbance scan, with an A330/280 ratio of 0.95 or higher considered a satisfactory preparation of ROH-rRBP, and an A338/280 ratio of 0.95 or higher considered a satisfactory preparation of RA-rRBP.

Western Blot

Apo-rRBP, serum-derived RBP (Athens Research and Technology, Cat # 16–16-180216) and recombinant human albumin (Sigma, Cat # A9731) were diluted into LDS 4X Sample buffer (NuPAGE), boiled and loaded into 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gel (NuPage) at a total protein concentration of 75 ng per well. SDS-PAGE was run in MES Running Buffer (50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% w/v SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.3) at 200 V for 35 minutes. Samples were transferred to 0.45 micron polyvinylidene difluoride membranes at 30 V for one hour before being collected and washed 3X at 5 minutes each in TBST (20 mM Tris, 135 mM NaCl, 0.1 % v/v Tween-20, pH 7.6). Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in blocking buffer (5% w/v non-fat dry milk (LabScientific) dissolved in TBST) before incubation at 4 °C overnight with either mouse monoclonal anti-human RBP4 (Abnova, 1:500 dilution, Cat # MAB3211) in blocking buffer or blocking buffer alone (for no-primary controls). After overnight staining, all membranes were washed 3X at 5 minutes each in TBST before secondary antibody incubation at room temperature for 1 hour in the dark with goat anti-mouse IgG IRDye 800CW (Li-Cor, 1:5000 dilution, Cat # 926–32210) antibody in blocking buffer. Probed membranes were washed 3X at 5 minutes each in TBST and subsequently imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey Imager.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Apo-rRBP was dialyzed into fluoride containing buffer (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaF, pH 7.4) and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. The protein (0.1 mg/mL for near UV measurements and 0.05 mg/mL for far UV measurements) was then loaded into a 1.0 mm cuvette and placed in an Aviv model 420 CD spectrometer operating at 25° C. All samples and buffers were scanned three times with a step size of 1 nm and a 5 s integration time, and then averaged to determine a mean CD signal. The mean CD signal from 0.22 μm filtered fluoride buffer was subtracted from the protein samples and the corrected data were converted to molar ellipticity using the exact concentration of apo-rRBP determined by absorbance. Data for near and far-UV were then combined to cover the entire range and the spectra smoothed by a 10 point Savitzky-Golay function.

Guanidine hydrochloride denaturation

Guanidine hydrochloride (GdmHCl) solutions (0 – 6 M) were prepared by volumetric dilution of 8 M GdmHCl stock (Sigma-Aldrich, 8 M, pH 8.5 in 50 mM bicine) into bicine-NaOH Buffer (50 mM bicine (Sigma-Aldrich), 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.5). Apo-rRBP, RA-rRBP and ROH-rRBP, prepared as described above, were diluted into the GdmHCl solutions to a final concentration of 500 nM rRBP. Samples were equilibrated for 7 days at room temperature in the dark. Fluorescence spectra were measured on a PTI QuantaMaster 40 fluorometer with excitation at 295 nm and emission from 315 nm to 500 nm. Spectra for three independent samples at each GdmHCl concentration were collected and averaged, with background subtracted. Unfolding was monitored by the change of intensity at the point of maximal signal difference between the folded and unfolded states (apo-rRBP, 320 nm; RA-rRBP, 360 nm; ROH-rRBP, 460 nm). The Gibbs free energy of unfolding was assumed to depend linearly on Gdm concentration, leading to a generalized expression for the equilibrium partition coefficient, where x and y represent the two different states, respectively (Eq 1):

| Eq (1) |

The fitted parameter, mxy, describes the dependence of free energy on denaturant concentration when transitioning from state x to y, and the fitted parameter represents the guanidine concentration at which the fraction of molecules in the two states, x and y, are equal. The Gibbs free energy change from state x to state y in the absence of denaturant, , is therefore defined as the product of mxy and . Apo-rRBP and RA-rRBP unfolding data were fit to a two-state unfolding model, N ↔ U (Eq 2):

| Eq (2) |

Em is the measured mean fluorescence intensity at a fixed [Gdm], and EmN and EmU are the fitted fluorescence intensity parameters describing the emission of the native, N, and unfolded, U, states. ROH-rRBP was fit to a three-state unfolding model, N ↔ I ↔ U (Eq 3):

| Eq (3) |

α relates the emission of the intermediate state, I, to the emission of the native and unfolded states, where α = (EmI − EmN)/(EmU − EmN). All other variables have similar interpretations as for the two-state unfolding model.

ROH-rRBP equilibrium binding constant

All measurements were collected with a PTI QuantaMaster 40 fluorometer at room temperature. Synthetic retinol was used immediately upon opening. Briefly, ROH was dissolved in ice cold ethanol and vortexed. The stock was diluted 100X into ice cold ethanol, and the concentration measured by absorbance at 325 nm. All samples were prepared in the dark and wrapped in aluminum foil. The concentration of ethanol was 2 % v/v when applied to the rRBP samples. ROH was added to apo-rRBP in PBS (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to produce a final rRBP concentration of 500 nM and incubated overnight at room temperature. rRBP tryptophan residues were excited at 295 nm and the tryptophan and retinol emission collected from 315 – 500 nm. All data points were corrected by background subtraction of the buffer, as ROH was not fluorescent in buffer under these conditions (data not shown). The data were fit to a mass action model (Eq 4), assuming one binding site of retinol per rRBP.

| Eq (4) |

Em is the measured mean fluorescence intensity at a fixed [ROH]t, and Emunbound and Embound are the fitted fluorescence intensity parameters describing the emission in the absence of ligand and at complete rRBP saturation, respectively. [rRBP]t is the total concentration of rRBP, [ROH]t is the total concentration of retinol and is the fitted apparent equilibrium dissociation constant.

ROH-rRBP-TTR equilibrium binding constant

All measurements were collected with a PTI QuantaMaster 40 fluorometer using polarizers at room temperature. ROH-rRBP solutions were prepared as described above. Recombinant human TTR (rTTR) was produced in PBS (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) as described elsewhere [16]. ROH-rRBP solutions were diluted into the rTTR stocks to a final ROH-rRBP concentration of 1 μM and variable rTTR concentrations between 0 and 4 μM. The fluorescence emission of bound retinol in ROH-rRBP was recorded using excitation at 330 nm and emission at 460 nm. The G-factor value was calculated for an rTTR-free sample of ROH-rRBP at 1 μM, and this value was held constant throughout the experiment [22]. Each sample was scanned 5 times over a 20 second period and the resultant values averaged to generate a single anisotropy value. This process was repeated with three independent samples in order to obtain a mean anisotropy and standard deviation. All data were fit to Eq (5), assuming n independent and identical sites on rTTR [23].

| Eq (5) |

r is the measured mean anisotropy at a fixed [rTTR]t, and runbound and rsat are the fitted fluorescence anisotropies of rRBP in the absence of rTTR and at complete rRBP saturation with rTTR, respectively. [rRBP]t is the fixed total concentration of rRBP, [rTTR]t is the fixed total concentration of rTTR added and is the fitted apparent equilibrium dissociation constant.

Results and Discussion

Recombinant Retinol Binding Protein Expression and Purification

Expression of recombinant human RBP (rRBP) in the pTWIN1 plasmid in BL23 E. coli cells produces an RBP fusion product that binds chitin with high affinity when applied at high pH and low temperature. Figure 2 shows the process flow diagram for this purification scheme, where the rRBP protein is eluted from the fusion construct through an intein-mediated self-cleavage by a drop in pH and an increase in temperature, allowing for recovery of rRBP with native human sequence without any N or C-terminal modification.

Figure 2:

Process flow diagram for rRBP expression and purification.

Induction of expression with IPTG directed rRBP fusion protein synthesis primarily towards insoluble inclusion bodies. The inclusion bodies were fully solubilized and denatured by overnight stirring in guanidine hydrochloride and DTT in order to maximize rRBP recovery as described elsewhere [12]. A titration of IPTG concentration in LB media showed diminishing returns on rRBP fusion protein yields at concentrations greater than 750 μM, as measured by SDS-PAGE of the reduced and denatured samples (data not shown).

On-column refolding by equilibration into native buffer in the absence of retinol was not sufficient to ensure proper refolding of the rRBP fusion protein prior to intein cleavage. Specifically, we attempted to refold on-column at several different pH and temperature conditions; in all cases, refolding in the absence of retinol subsequently resulted in almost no intein cleavage of the fusion protein, and of the protein that did cleave, attempts to generate the holo protein by addition of retinol resulted in protein that lacked the characteristic 1:1 A330/280 absorbance ratio of serum RBP (data not shown). Our results are consistent with others who have reported that RBP refolds poorly in the absence of retinol [12, 14]. Therefore the fusion protein was re-folded in the presence of retinol. Briefly, solubilized, denatured, and reduced rRBP fusion protein was diluted to a final GdmHCl concentration of 1M in an oxidative refolding buffer containing retinol (ROH), and allowed to refold in the cold for 5 hours prior to column loading. Washing with a high salt buffer was sufficient to remove cellular protein contaminants. Decreasing the pH to 6.5 and warming to room temperature successfully directed the fusion construct intein tag to undergo C-terminal peptide bond cleavage, releasing the full-length ROH-rRBP. SDS-PAGE analyses of the cell lysate, various effluents and the purified ROH-rRBP are shown in Figure 3A. The fusion construct does not undergo premature cleavage and binds to the chitin column with high recovery, based on the absence of fusion protein in the lysate flow through. The A330/280 of the purified protein was slightly higher than 1.0 (not shown), consistent with other reported recombinant preparations [11, 12] and with preparations derived from human serum [19, 24–26].

Figure 3:

A) SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Lanes 1 and 7, molecular weight standard; lane 2, cell lysate; lane 3, lysate flow through; lane 4, wash effluent; lane 5, ROH-rRBP after intein cleavage; lane 6, chitin bead regeneration effluent. The approximate expected position of the fusion protein (45 kDa) and rRBP (21 kDa) are indicated by labels. B) Western blot of apo-rRBP, serum-derived RBP and human albumin controls (75 ng of protein loaded per well). Lanes 5 – 8 were run on the same gel as lanes 1 – 4 but were separated after blocking to serve as no-primary controls processed in parallel with lanes 1 – 4. Lanes 1 and 8, MagicMark molecular weight standard; lanes 2 and 5, serum-derived RBP; lanes 3 and 6, human recombinant albumin; lanes 4 and 7, apo-rRBP. The expected molecular weight of human recombinant albumin is ~ 67 kDa.

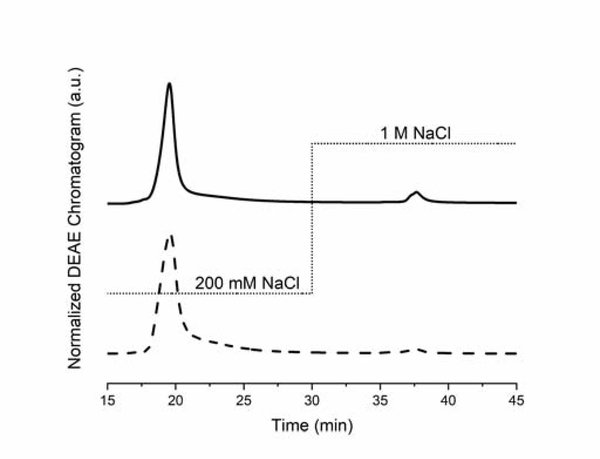

Other researchers have reported that refolding of recombinant RBP partially results in formation of incorrectly folded protein that must be removed by anion exchange chromatography [12, 14]. Besides displaying different surface charge, these alternate folds have non-native A330/280 ratios and different ROH binding and release kinetics [14]. To test the purity of refolded protein produced under our protocol, we analyzed the product from the chitin column with a salt step gradient purification on a DEAE anion exchange column. We detected only a very minor contaminant that eluted at high salt and with low A330/280 ratio (Figure 4). We conclude that the DEAE polishing step is not required for our process, a conclusion supported by the fact that the equilibrium constants for ROH binding to rRBP purified with and without the DEAE step were statistically indistinguishable (Supplemental Table S1 and Figure S5). Thus, active and correctly folded rRBP is achieved with our protocol using only a single adsorption step.

Figure 4:

DEAE chromatogram of eluted ROH-rRBP at 280 nm (solid line) and 330 nm (dashed line). The absorbance data were collected independently by two successive injections of the same stock of eluted ROH-rRBP, and each chromatogram was normalized by the maximum signal for that particular run. The dotted line indicates the salt gradient applied to elute the protein fractions.

Production of apo-rRBP and Reconstitution of holo-rRBP

Retinol was removed from the protein product by diethyl ether (DEE) solvent extraction to produce apo-rRBP, evidenced by complete elimination of the absorbance peak at 330 nm (Figure 5). The apo-protein molecular weight was determined by mass spectrometry as 21,065.4 Da (Supplemental Figure S1), identical to the expected molecular weight of 21,065.4 Da calculated from the known amino acid sequence. Western blotting of DEE-extracted apo-rRBP (Figure 3B) confirmed that apo-rRBP presents identically as serum RBP to anti-RBP4 monoclonal antibody.

Figure 5:

Absorbance spectra of DEE and reconstituted rRBP: 12.5 μM apo-rRBP (dashed line); 12.5 μM RA-rRBP (dotted line); 12.5 μM ROH-rRBP (solid line).

Little is known about whether DEE stripping of ROH from holo-RBP affects the structure and/or activity of RBP. Critically, it is unknown if stripped, then re-constituted, holo-ROH-RBP is identical to serum holo-RBP. Therefore, we completed characterization studies using stripped then reconstituted holo-rRBP. Serum RBP binds not only retinol but also other retinol derivatives, such as retinoic acid (RA), which has been used as a substitute for retinol in some studies because it is more chemically stable. We verified that both of these ligands bind to DEE-extracted apo-rRBP. Absorbance spectra for apo-rRBP alone or reconstituted with RA or ROH are shown in Figure 5. Apo-rRBP can be reconstituted with ROH at an A330/280 ratio of ~1.0, indicating DEE stripping does not interfere with the retinol binding pocket environment. Upon binding of ROH, the 280 nm signal significantly increases, as expected [11], and binding of RA displays a red shift in the maximum wavelength absorbance, consistent with previous studies on serum-derived RBP [26]. Analytical size exclusion chromatography of both apo-rRBP and reconstituted ROH-rRBP demonstrates that the purification and DEE stripping processes do not introduce aggregates into the rRBP population, as rRBP elutes in a single peak (Supplemental Figure S6).

Characterization of rRBP structure and function

Preparations of recombinant RBP indicate a wide breadth of physicochemical parameters, even though the A330/280 ratios reported are similar [9–14, 27]. As shown in Table 1, a variety of approaches have been used to produce recombinant RBP. For use in mechanistic studies, it is important that the recombinant RBP mimic the native serum RBP in both structure and function. ROH-rRBP purified from serum shows an A330/280 ratio of ~1.0, indicative of retinol binding, and several investigators have used the absorbance scan to demonstrate native fold. However, native disulfide bonds are not necessary for retinol binding activity [27], so analysis of rRBP activity simply by confirmation of ROH binding may overlook other dissimilarities to native RBP that can influence stability, release kinetics and/or equilibrium dissociation constants. Given this, we undertook a comprehensive biophysical characterization of our rRBP and compared results against serum RBP, if possible, and/or other recombinant preparations. Table 3 contains a summary of these analyses, which are described in greater detail below.

Table 3:

Physicochemical characterization of rRBP against human serum sources

| Reference | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | [13] | This work | Serum Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | SDS-Page | SDS-Page Mass Spectrometry |

SDS-Page, | SDS-Page, Mass Spectrometry | SDS-Page, Mass Spectrometry | SDS-Page, Mass Spectrometry | N/A |

| Identity | N-terminal sequencing | Western Blot | Immunodetection, N-terminal sequencing | NR | Western Blot | Immunoblot | N/A |

| Purity | SDS-Page | SDS-Page | SDS-Page | SDS-Page | SDS-Page | SDS-Page | N/A |

| 2° Structure | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | CD Spectra | CD Spectra[28] |

| [Gdm]50NU | 2.0 M Apo 2.4 M RA-rRBP |

NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.75 M Apo 2.57 M RA-rRBP |

1.79 M Apo[29],c |

| A330/280 | NR | ∼ 1.0 | ∼ 1.0 | ∼ 1.0 | NR | ∼1.0 | ∼1.0[19–21] |

| rRBP | 210 nM (RA) | NR | 80 nM | NR | 200 nM | 100 nM | ∼150 – 190 nM[18] |

| ROH-rRBP | NR | NRa | NR | NRb | NR | 250 nMd | ∼230 nM[31] ∼340 nM[32],d |

NR = Not Reported.

rRBP bound to immobilized TTR.

Sedimentation of rRBP-TTR complexes was observed.

used human rRBP.

used human rTTR

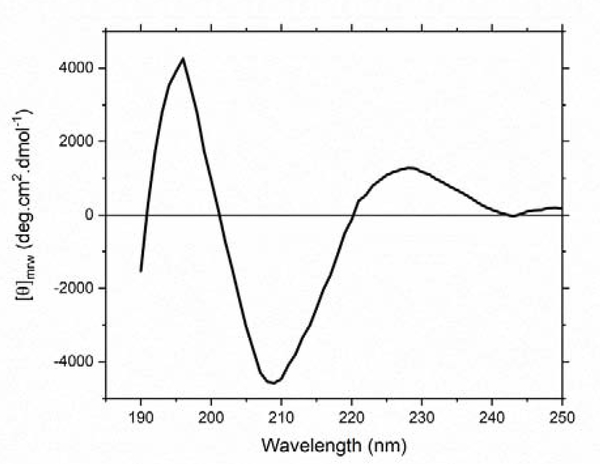

rRBP secondary structure and stability

Secondary structure of apo-rRBP was evaluated by circular dichroism (CD) (Figure 6). CD spectra of serum RBP (stripped of retinol by solvent extraction) have been reported previously [28] and served as a model for comparison. Apo-rRBP shows a positive molar ellipticity between 220 and 235 nm, unusual for other β-rich proteins, but an exact match with RBP isolated from serum and stripped by organic solvent. Similarly, the peak at 196 nm and the well at 208 nm match the spectra of serum RBP. The high β-sheet content CD spectra also agrees with the expected tertiary structure based on apo and holo RBP crystal structures [1], which indicate serum apo/holo RBP form a β-barrel structure motif.

Figure 6:

Circular Dichroism (CD) spectra of apo-rRBP at 25° C. The sample was prepared in phosphate buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaF, pH 7.4) at a final protein concentration of 0.1 mg/mL (near UV) or 0.05 mg/mL (far UV). Data were corrected for concentration by conversion to molar ellipticity and merged.

Next we evaluated the stability of rRBP against chemical denaturation, and the effect of ligands RA and ROH on stability. Because rRBP contains disulfide bonds that can reshuffle if reduced, all samples were denatured in the absence of any reducing agent. It has been previously reported that RA binding increases the stability of apo-RBP against GdmHCl unfolding [9], but to date no data on the effect of ROH have been published. We prepared rRBP in the presence and absence of ligands and monitored fluorescence emission as a function of GdmHCl concentration; for apo-rRBP and RA-rRBP, tryptophan emission was tracked, and for ROH-rRBP, ROH fluorescence emission was tracked (Supplemental Figure S2, panels A, B and C). Protein denaturation was fit to a two-state unfolding model for apo-rRBP and RA-rRBP (Eq 2), and a three-state unfolding model for ROH-rRBP (Eq 3). There are four tryptophan residues within human RBP, all of which contribute to fluorescence emission, so the change in signal with addition of GdmHCl represents the summed contribution of the changes in local environment for each residue. Trp 24 (see Figure 1) is located in a highly hydrophobic environment, and has been shown to contribute strongly to rRBP tryptophan fluorescence [29]. Trp 24 becomes solvent exposed upon unfolding, and this process is captured by the m-value parameter in Eqns 2 & 3, which is correlated with the increase in accessible surface area when transitioning from the native to the denatured state [30]. The data are displayed in Figure 7 as a fraction folded versus GdmHCl concentration, and fitted parameters are shown in Table 2.

Figure 7:

Guanidine hydrochloride unfolding of apo-rRBP (open circle), RA-rRBP (filled circle) and ROH-rRBP (open circle with cross hatch). The solid curves are least-square regression fits to a two-state unfolding model (apo-rRBP and RA-rRBP, Eq 2), or a three-state unfolding model (ROH-rRBP, Eq 3).

Table 2:

rRBP Unfolding Values

| Apo-rRBP | RA-rRBP | ROH-rRBP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism (xy) | N ↔ U | N ↔ U | N ↔ I | I ↔ U |

| mxy (kJ/mol M) | 10 ± 1 | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 18 ± 1 | 5.5 ± 0.4 |

| [Gdm]50xy (M) | 1.75 ± 0.03 | 2.57 ± 0.02 | 2.36 ± 0.02 | 3.57 ± 0.08 |

| (kJ/mol) | 17 ± 2 | 32 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 20 ± 1 |

for apo-rRBP was found to be 1.75 ± 0.03 M, in good agreement with literature values for porcine rRBP (2.0 M) [9] and human rRBP (1.79 M) [29]. Binding of RA stabilized the protein, as evidenced by the increase in concentration to 2.57 ± 0.02 M, which is also in good agreement with porcine rRBP data [9]. This corresponds to an RA-induced increase in stability of the native state by +15 kJ/mol. Binding of ROH stabilized the protein even further, as evidenced by the net increase of +45 kJ/mol compared to apo-rRBP when the effects of each folding step are added together.

These results must be interpreted with caution, as unfolding was tracked by tryptophan fluorescence for apo-rRBP and RA-rRBP, but by retinol fluorescence for ROH-rRBP. Tryptophan emission was quenched by increasing Gdm concentration for apo-rRBP, but for RA-rRBP, at least one tryptophan residue, likely Trp 24 (see Figure 1), participates in resonance energy transfer (RET) to bound RA [18]; RET effectively lowers the net tryptophan fluorescence emission compared to apo-rRBP. While RA remains bound to rRBP, tryptophan emission is significantly lower than apo-rRBP at a given Gdm concentration, but when RA dissociates and rRBP shifts to apo-rRBP, the observed emission increases, likely due to the large contribution Trp 24 makes to the overall rRBP tryptophan fluorescence. Given these competing effects of quenching and loss of RET, the change in tryptophan emission upon addition of Gdm reflects the transition from the ligand-bound, native state to the unbound, unfolded state: N − RA ↔ U + RA. Therefore, the calculated Gibbs free energy change, , is a combination of the Gibbs free energy change of unfolding and RA dissociation. This is supported by the higher m-value for RA-rRBP than apo-rRBP, indicating RA-rRBP has a larger increase in accessible surface area when transitioning from RA-rRBP to the denatured and dissociated state.

With ROH-rRBP, similar to RA, at least one tryptophan residue participates in RET to ROH; in this case, however, ROH is fluorescent, and we considered ROH emission as well as the tryptophan emission as an indicator of rRBP unfolding. Fitting of either the tryptophan or ROH data to the two-state unfolding model (Eq 2) was poor, with the model providing non-random residuals; a three-state unfolding mechanism (Eq 3) resulted in a much better fit, with random residuals (Supplemental Figure S3). Because ROH emission is dependent on dissociation, the unfolding model is similar to that of RA, but with an unknown intermediate: N − ROH ↔ I ↔ U + ROH. is again a combination of the energetics of unfolding and ROH dissociation. is the sum of and contributions, but mechanistic interpretation of these values or the corresponding m-values is not possible without identification of the nature of the intermediate specie, I. We speculate that the intermediate specie is partially or fully unfolded, but still ROH-associated. Regardless, the fact that the data for RA-rRBP unfolding appears two-state whereas ROH-rRBP unfolding must be modeled as three-state is novel; this suggests that ROH remains associated with rRBP, even at high denaturant concentrations, but RA does not. This observation is consistent with the fact that apo-rRBP has higher affinity for ROH than RA [18].

Quantitation of rRBP binding to retinol and transthyretin

For rRBP to mimic serum RBP in carrying out its biological functions, it must bind to retinol and to TTR with affinities equal to that of native RBP. The equilibrium dissociation constant for retinol binding to rRBP was determined by resonance energy transfer (RET) between retinol and rRBP tryptophan (Figure 8).

Figure 8:

Retinol (ROH) binding to apo-rRBP monitored by emission of ROH at 460 nm as an acceptor in resonance energy transfer (RET) from donor rRBP tryptophan. Data are fit by nonlinear regression to a mass action model (Eq 4), assuming one binding site of ROH per molecule of rRBP, yielding a dissociation constant, , of 100 ± 30 nM.

The dissociation constant of the ROH-rRBP complex was found to be 100 ± 30 nM, assuming one binding site of retinol per apo-rRBP. The RET donor in this assay is tryptophan spatially located near the retinol molecule, likely Trp 24 (see Figure 1), and the decrease in tryptophan emission can also be tracked as a method for determining the dissociation constant. The corresponding curve (Supplemental Figure S4) generates a similar (Supplemental Table S1). This value is in close agreement with recent porcine apo-RBP binding studies [33] and recombinant human apo-RBP binding studies [11]. Earlier investigations with both recombinant and serum-derived RBP reported ~200 nM [18]. This discrepancy can be explained by the model selection for ROH binding. We assumed a 1:1 stoichiometry between ROH and rRBP, and fitted the data accordingly using a nonlinear model. Earlier investigators assumed an unknown number of binding sites and fitted using a linearized model, the result of which yields values of lower certainty. These investigators reported sub-1:1 binding stoichiometry of ROH to RBP [13, 18], suggesting that a fraction of their preparations were not correctly folded and did not bind ROH. Furthermore, in the recombinant preparations that do not report A330/280 ratios or provide structural characterization, there is no evidence of proper disulfide formation that enables serum-like affinity for ROH, which can affect retinol release [14, 27]. In the case of A330/280 ratios, we corroborated these findings, as refolded ROH-rRBP samples with ratios of 0.7 or less prior to DEE extraction, typical of attempted on-column refolding in an oxidative buffer containing ROH rather than by rapid dilution and stirring prior to column loading, were consistently found to display different apparent binding capacities for ROH compared to samples with a refolded ratio of ~ 1.0 produced by the methods outlined above (data not shown). These data often fit poorly to the model in Equation 4 unless a significant portion, up to 50%, of rRBP was assumed to be unable to bind ROH; this suggests that rRBP final products demonstrating A330/280 ratios lower than ~1.0 may be composed of an ensemble of rRBP conformations, some of which may not be active.

We next measured the equilibrium dissociation constant for binding of ROH-rRBP to TTR using fluorescence anisotropy (Figure 9). The data were fit to a mass action model assuming n independent, identical sites per TTR tetramer. The fitted value n = 1.8 ± 0.2 is in good agreement with in vitro and in vivo observations of two available holo-RBP binding sites per TTR tetramer [23, 34]. of 250 ± 60 nM is consistent with previous reports of serum-derived holo-RBP:TTR complex ( = 230 nM and n = 1.9) [31].

Figure 9:

ROH-rRBP binding to TTR measured by fluorescence anisotropy. Data are fit to a mass action model (Eq 5) with n independent, identical ROH-rRBP binding sites per TTR molecule. Fitted parameters are = 250 ± 60 nM and n = 1.8 ± 0.2.

Conclusion

We report a simple process for recombinant production of human RBP. Our protocol is superior to previously reported methods for two primary reasons: first, the purified rRBP exhibits the fully native human sequence; second, purification of native rRBP is achieved in a simple one-step chromatographic process. Furthermore, we have characterized relevant biophysical properties of our rRBP in much greater detail than in previous reports, ensuring that its structure and function are good replicas of native human protein. Finally, we have shown that ROH-rRBP and RA-rRBP exhibit different behavior in the presence of chemical denaturants, a novel discovery.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Human retinol-binding protein with native sequence is produced using an intein system.

Folded protein is purified in a simple one-step process.

Properties of recombinant retinol-binding protein are characterized in detail.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center’s Pilot Funding Program and UW-Madison Biotechnology Training Program (NIH 5 T32 GM008349). CD spectra were obtained at the University of Wisconsin - Madison Biophysics Instrumentation Facility, which was established with support from the University of Wisconsin - Madison and grants BIR-9512577 (NSF) and S10 RR13790 (NIH), with technical assistance provided by Dr. Darrell McCaslin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zanotti G and Berni R, Plasma retinol-binding protein: Structure and interactions with retinol, retinoids, and transthyretin. Vitamins and Hormones - Advances in Research and Applications, Vol 69, 2004. 69: p. 271–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newcomer ME and Ong DE, Plasma retinol binding protein: structure and function of the prototypic lipocalin. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 2000. 1482(1–2): p. 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perduca M, et al. , Human plasma retinol-binding protein (RBP4) is also a fatty acid-binding protein. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids, 2018. 1863(4): p. 458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman DS, Vitamin A and retinoids in health and disease. N Engl J Med, 1984. 310(16): p. 1023–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makover A, et al. , Localization of retinol-binding protein messenger RNA in the rat kidney and in perinephric fat tissue. J Lipid Res, 1989. 30(2): p. 171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidsson P, et al. , Proteome analysis of cerebrospinal fluid proteins in Alzheimer patients. Neuroreport, 2002. 13(5): p. 611–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noy N, Vitamin A in regulation of insulin responsiveness: mini review. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 2016. 75(2): p. 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghu P, Ravinder P, and Sivakumar B, A new method for purification of human plasma retinol-binding protein and transthyretin. Biotechnol Appl Biochem, 2003. 38(Pt 1): p. 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller HN and Skerra A, Functional expression of the uncomplexed serum retinol-binding protein in Escherichia coli. Ligand binding and reversible unfolding characteristics. J Mol Biol, 1993. 230(3): p. 725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivaprasadarao A and Findlay JB, Expression of functional human retinol-binding protein in Escherichia coli using a secretion vector. Biochem J, 1993. 296 ( Pt 1): p. 20915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang TT, Lewis KC, and Phang JM, Production of human plasma retinol-binding protein in Escherichia coli. Gene, 1993. 133(2): p. 291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie YS, et al. , Recombinant human retinol-binding protein refolding, native disulfide formation, and characterization. Protein Expression and Purification, 1998. 14(1): p. 3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wysocka-Kapcinska M, et al. , Expression and characterization of recombinant human retinol-binding protein in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr Purif, 2010. 71(1): p. 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaguchi R, Zhong M, and Sun H, Real-time analyses of retinol transport by the membrane receptor ofplasma retinol binding protein. J Vis Exp, 2013(71): p. e50169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlenfein TJ and Murphy RM, Expression, purification, and characterization of human cystatin C monomers and oligomers. Protein Expr Purif, 2016. 117: p. 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, et al. , Differential modification of Cys10 alters transthyretin’s effect on beta-amyloid aggregation and toxicity. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2009. 22(8): p. 479–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lessard JC, Growth media for E. coli. Methods Enzymol, 2013. 533: p. 181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cogan U, et al. , Binding Affinities of Retinol and Related Compounds to Retinol Binding-Proteins. European Journal of Biochemistry, 1976. 65(1): p. 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson PA and Berggard I, Isolation and properties of a human retinol-transporting protein. J Biol Chem, 1971. 246(1): p. 25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Futterman S and Heller J, The enhancement of fluorescence and the decreased susceptibility to enzymatic oxidation of retinol complexed with bovine serum albumin, - lactoglobulin, and the retinol-binding protein of human plasma. J Biol Chem, 1972. 247(16): p. 5168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berni R, Ottonello S, and Monaco HL, Purification of human plasma retinol-binding protein by hydrophobic interaction chromatography. Anal Biochem, 1985. 150(2): p. 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakowicz JR, Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 2010, New York: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folli C, Favilla R, and Berni R, The interaction between retinol-binding protein and transthyretin analyzed by fluorescence anisotropy. Methods Mol Biol, 2010. 652: p. 189–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanai M, Raz A, and Goodman DS, Retinol-binding protein: the transport protein for vitamin A in human plasma. J Clin Invest, 1968. 47(9): p. 2025–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rask L, Vahlquist A, and Peterson PA, Studies on two physiological forms of the human retinol-binding protein differing in vitamin A and arginine content. J Biol Chem, 1971. 246(21): p. 6638–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horwitz J and Heller J, Interactions of all-trans, 9-, 11-, and 13-cis-retinal, all-trans-retinyl acetate, and retinoic acid with human retinol-binding protein and prealbumin. J Biol Chem, 1973. 248(18): p. 6317–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reznik GO, et al. , Native disulfide bonds in plasma retinol-binding protein are not essential for all-trans-retinol-binding activity. J Proteome Res, 2003. 2(3): p. 243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bychkova VE, et al. , Retinol-binding protein is in the molten globule state at low pH. Biochemistry, 1992. 31(33): p. 7566–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene LH, et al. , Role of conserved residues in structure and stability: tryptophans of human serum retinol-binding protein, a model for the lipocalin superfamily. Protein Sci, 2001. 10(11): p. 2301–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholtz JM, Grimsley GR, and Pace CN, Solvent denaturation of proteins and interpretations of the m value. Methods Enzymol, 2009. 466: p. 549–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malpeli G, Folli C, and Berni R, Retinoid binding to retinol-binding protein and the interference with the interaction with transthyretin. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 1996. 1294(1): p. 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanotti G, et al. , Structural and mutational analyses of protein-protein interactions between transthyretin and retinol-binding protein. FEBS J, 2008. 275(23): p. 5841–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noy N and Xu ZJ, Interactions of Retinol with Binding-Proteins - Implications for the Mechanism of Uptake by Cells. Biochemistry, 1990. 29(16): p. 3878–3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monaco HL, The transthyretin-retinol-binding protein complex. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 2000. 1482(1–2): p. 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.