Abstract

Homogenized hydroponic ginseng (HG) fortified with poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) was produced by a two-step fermentation using Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum. For optimized production of bioactive compounds, the precursor monosodium L-glutamate (MSG) as well as nutrients such as glucose and skim milk were added. The homogenized HG was pH 6.93 and had an acidity of 0.08%, and viable cell count of 6.13 log colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL. The first (alkaline) fermentation was performed at 42°C for 2 days in the presence of 5% MSG and 2% glucose. The fermented HG was pH 8.08 and had an acidity of 0.03%, a mucilage of 2.13%, a consistency of 0.79 Pa·sn, and viable cell count of 8.53 log CFU/mL. For the second (lactic) fermentation, the fermented HG was fortified with 5% skim milk, inoculated with 7.54 log CFU/mL of L. plantarum EJ2014, and was incubated at 30°C for 5 days; the resulting in pH 5.63 and had and acidity of 0.35, and viable cell count of 6.71 log CFU/mL (B. subtilis) and 9.23 log CFU/mL (L. plantarum). Moreover, MSG was completely bio-converted with producing 1.03% GABA. Therefore, novel co-fermentation using B. subtilis HA and L. plantarum EJ2014 fortified HG with functional components including γ-PGA, GABA, peptides, and probiotics.

Keywords: hydroponic ginseng, Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus plantarum, γ-PGA, GABA

INTRODUCTION

Ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer) has been used in oriental countries for a long time because it is regarded as an excellent medicinal material for regulating fatigue and strengthening the nervous, circulatory, and metabolic systems (Nam, 2002). Ginseng has also been reported to have anticancer properties (Kikuchi et al., 1991), enhance of liver function (Oura and Hiai, 1973), regulate the immune function (Singh et al., 1984), show antidiabetic (Zhang et al., 1990), antioxidative, and anti-aging (Oh et al., 1992) effects, and to help control blood pressure (Kang and Kim, 1992).

Hydroponic cultivation of ginseng has advantages such as generating lower pollution and having a faster time to harvest. Hydroponic cultivation of various crops such as strawberry, ginseng, and cherry tomato has been performed successfully by optimizing the composition of the growing medium, the wavelength of the artificial light, and the temperature of the cultivation; changes to these factors can also affect the composition of the crop (Choi and Cho, 2015; Song, 2014; Jeon, 2018; Kim, 2014). It has been reported that ginseng cultivated hydroponically for 4 months contains more than 6 times the ginsenosides of ginseng cultivated in a field for 4 years (Kim et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2008). In addition, studies of ginseng have mainly focused on roots, but the leaves and stems, which are considered byproducts, are also rich in ginsenosides.

As human lifespans increase, interest in foods to promote health have also increased. Fermentation technologies using various microorganisms to develop health foods have attracted domestic and international attention (Park, 2012). In addition to the foods themselves, there is interest in the products generated by enzymatic degradation of the raw material as well as in the various metabolites biosynthesized by the microbial strains (Lee and Jeon, 1998). In addition, lactic acid bacteria are generally recognized as safe (Tsushida and Murai, 1987).

Among the useful fermenting microorganisms, Bacillus subtilis are mainly involved in soybean fermentation to make foods such as cheonggukjang and are used for commercial production of enzymes in the food industry. Specifically, poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA), a biodegradable viscous substance produced by B. subtilis, has shown moisturizing, anionic and non-toxic properties, and is used as an ingredient in functional foods and cosmetics.

Lactobacillus plantarum, which is mainly involved in kimchi fermentation, is a valuable strain of bacteria that efficiently converts monosodium L-glutamate (MSG) into γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). GABA is produced by decarboxylation of glutamate by the intracellular glutamate decarboxylase enzyme and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate as a coenzyme (Yokoyama et al., 2002; Bown and Shelp, 1997). GABA has been reported to exert its pharmacological effects when delivered in amounts of 50~200 mg (Choi and Cho, 2015). Agricultural products such as sprouted beans and green tea contain GABA, but in insufficient amounts to show bioactivity. Studies using Lactobacillus for fermentation of Camellia leaves and restricted media have reported high concentrations of GABA (Tsushida and Murai, 1987; Li et al., 2010). However, no studies investigating GABA production by lactic acid bacteria have used hydroponic ginseng as the raw material.

Therefore, we optimized two-step fermentation using B. subtilis HA and L. plantarum EJ2014 to fortify the functional compounds in hydroponic ginseng. The first alkaline fermentation was performed to produce γ-PGA from B. subtilis, followed by a lactic fermentation to produce GABA and peptides from L. plantarum. Hydroponic ginseng-based functional product containing γ-PGA, GABA, peptides, and probiotics are expected to be generated by the novel co-fermentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Hydroponic ginseng grown for 2 years was supplied by DK Eco-Farm Co., Ltd. (Cheonan, Korea), and stored at −20°C until use. MSG was purchased from CJ Cheil-Jedang Corp. (Seoul, Korea). Glucose was obtained from Samyang Foods, Inc., (Seongnam, Korea) and skim milk powder was obtained from Seoul Milk (Seoul, Korea). The culture medium was purchased from Becton, Dickinson and Company (Sparks, MD, USA). GABA was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and glutamic acid as an amino acid standard was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Dextran was purchased from American Polymer Standards (Mentor, OH, USA).

Strains and starter manufacture

B. subtilis HA (KCCM 10775P), used for the first alkaline fermentation, was isolated from traditional cheonggukjang and deposited in the Korean Culture Center of Microorganisms (KCCM). B. subtilis HA was incubated in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar at 42°C for 24 h; subsequently, a single colony was inoculated on nutrient broth that had been sterilized at 121°C for 15 min and cultured at 42°C and 160 rpm for 24 h. To prepare a 10-fold concentrated starter, the B. subtilis HA cultured medium was centrifuged (Supra 21K, Hanil Science Industrial Co., Ltd., Gimpo, Korea) at 7,000 rpm for 20 min, and the cell pellet was dispersed in sterilized water.

L. plantarum EJ2014 (KCCM 11545P) was isolated from rice germ (Rice Mill, Uljin, Korea) and deposited in the KCCM. This strain was cultured on an MRS agar plate at 30°C for 24 h. A single colony was inoculated in a sterilized MRS broth using a loop. After 24 h, this culture was used as a starter.

Hydroponic ginseng alkaline fermentation

Ginseng roots and leaves were homogenized with water using a mixer (SMX-3610WS, Shinil Inc., Seoul, Korea) to prepare 5% hydroponic ginseng (HG) homogenate (w/v). Then, 80 mL of the homogenate was sterilized at 121°C for 15 min. MSG (5%, v/v) as a precursor and glucose (2%, v/v) as a nutrient were then added, the volume was adjusted to 100 mL with distilled water, and the medium was sterilized. Subsequently, B. subtilis HA starter (2%, v/v) was inoculated and cultured at 42°C and 160 rpm for 2 days in a shaking incubator (SI-900R, Jeio Tech. Co., Ltd., Daejeon, Korea).

Two-step fermentation using B. subtilis HA and L. plantarum EJ2014

Sterilized 10% skim milk solution (w/v) was added to the HG broth fermented by B. subtilis HA, to a final concentration of 5% (v/v). This medium was then inoculated with 1% starter of L. plantarum EJ2014 and cultured at 30°C for 5 days in an incubator (IS-971R, Jeio Tech Co.).

pH, acidity, and bacterial count

The pH was measured using a pH meter (SevenEasy pH, Mettler-Toledo AG, Columbus, OH, USA). The acidity was measured by diluting samples 10 times in distilled water, titrating with 0.1 N NaOH until reaching pH 8.3, and calibrating the titration using an organic acid factor (lactic acid=0.0090).

To determine bacteria count, samples were diluted with sterilized distilled water and 20 μL of 104, 105, and 106 diluted samples were spread on MRS agar plates. Plates were incubated at 42 or 30°C for B. subtilis or L. plantarum, respectively. After 24 h, the colonies were counted and expressed as log colony-forming units (CFU)/mL.

Tyrosine content

To measure peptide production in the fermented HG, the Folin phenol reagent method was carried out (Choi et al., 2004), using tyrosine as the standard. Supernatants obtained by centrifugation (model 5415R, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) were used as the samples. Sample (0.7 mL) and 0.44 M trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 0.7 mL) were mixed at 37°C for 30 min to precipitate undegraded proteins, and insoluble solids were removed through centrifugation (model 5415R, Eppendorf AG) for 10 min. A 1 mL aliquot of the recovered supernatant was alkalized by adding 2.5 mL of 0.55 M Na2CO3, and mixed with 0.5 mL of 3 times diluted Folin phenol reagent at 37°C for 30 min. After the reaction had cooled to room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 660 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Ultrospec® 2100 pro, Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA). The standard calibration curve was used to calculated the tyrosine content by substituting y=0.0081x+0.0115 (R2=0.999) (Eq. 1).

| (Eq. 1) |

where OD is optical density.

Qualitative analysis of L-glutamic acid and GABA using TLC (thin layer chromatography)

MSG and GABA were qualitatively analyzed using a silica gel TLC plate (10×20 cm, 60 F254 25 aluminum sheets, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The supernatants of 2 times diluted fermented HG, L-glutamic acid and GABA standards were each spotted (2 μL each) on TLC plates. Plates were developed in a chamber (30×25×10 cm3) using 3:1:1 (v/v) n-butyl alcohol: acetic acid glacial: distilled water as a solvent. A 0.2% ninhydrin solution (w/v) was sprayed as the color development reagent. The MSG and GABA spots were identified after drying at 90°C for 5~10 min.

Quantitative analysis of L-glutamic acid and GABA using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Fermented HG (1 g) was mixed with 10 mL of 6 N hydrochloric acid, and hydrolysis was conducted for 22 h at 110°C. After filtration, 10 μL of extract was mixed with 70 μL of borate buffer and 20 μL of AccQ-Fluor Reagent (Waters, New York, NY, USA) for 10 s, and allowed to stand for 1 min. This mixture was then heated at 55°C for 10 min in an oven for derivation. Derivatized samples were cooled to room temperature and were analyzed by HPLC (Alliance 2695, Waters) using an AccQ·Taq™ (3.9×150 mm) column. AccQ·Taq eluent A (Waters), acetonitrile, and 3 times distilled water were used as the mobile phase. The GABA and glutamic acid standards were dissolved in distilled water to prepare calibration curves, and the contents of each compound were calculated using Eq. 2:

| (Eq. 2) |

where S is the concentration of the sample (μg/mL), V is the sample volume (mL), D is the fold dilution, and W is the weight of the harvested sample (g).

Determination of mucilage and molecular weight

Fermented HG (5 g) was centrifuged (Supra 21K) at 10°C and 15,000 rpm for 20 min to remove cells and insoluble components. Viscous supernatants were mixed by adding 2 times the volume of isopropyl alcohol. The recovered material was dried at 50°C in a hot air dryer for 1 day (Shih et al., 2002), pulverized using a mixer (M20 Universal Mill, IKA-Werke Gmbh & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany) and diluted with distilled water to form a 0.5% solution (w/v).

HPLC analysis was performed using an SB-805 HQ column (Shodex, Tokyo, Japan) with 0.1 M NaNO3 as the mobile phase. A standard calibration curve (y=−0.8819x +15.04, R2=0.993) was generated with dextran of 1,010, 5,300, 7,200, 45,800, 178,000, and 990,000 Da, and used to calculate the molecular weight of γ-PGA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (Ver. 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The significance of the results was determined using Duncan’s multiple range test. P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Composition of ginseng

The 5% HG exhibited a characteristic ginseng flavor and a greenish color due to the chlorophyll extracted from the leaves. The homogenized HG was pH 5.97, had a 92.7% moisture content, a 0.22% protein content, and a 0.05% crude fat content. The most abundant mineral in homogenized HG was potassium (8.28 mg/100 mL), consistent with a previous report (Kim et al., 2002).

GABA production by single fermentation with L. plantarum EJ2014

For production of GABA by single fermentation with L. plantarum EJ2014, 3% glucose and 0.2% yeast extract were added to the 5% HG as nutrients, and 3% MSG was added as a precursor. The L. plantarum starter was inoculated at 6.05 log CFU/mL. The initial pH was 6.53, and the pH gradually decreased to 4.37 after 7 days of lactic acid fermentation. Thereafter, no changes in pH were observed during 30 days of lactic fermentation.

The viable cells of L. plantarum EJ2014 increased to 9.52 log CFU/mL after 4 days, then decreased to 7.72 log CFU/mL after 30 days (data not shown).

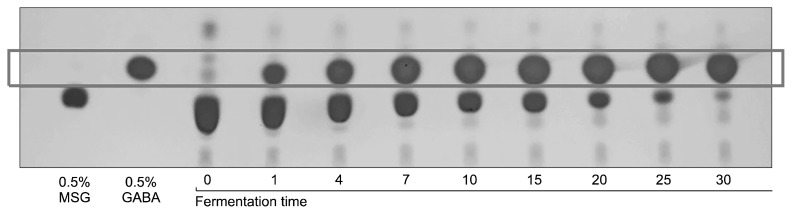

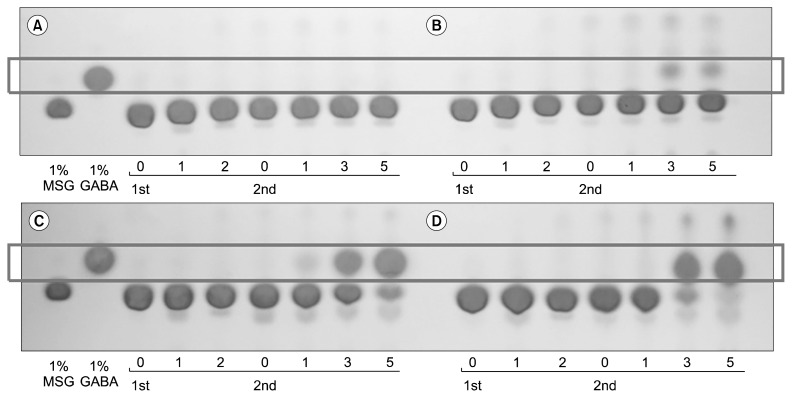

GABA conversion was monitored using TLC, and almost all MSG was converted to GABA after 30 days. These results indicate that single lactic acid fermentation requires a long time to bio-convert GABA from the MSG precursor (Fig. 1). Therefore, we optimized production of GABA by shortening the fermentation period through two-step co-fermentation using B. subtilis and L. plantarum.

Fig. 1.

γ-Aminobutyric acid production pattern of hydroponic ginseng fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014.

Optimization of GABA production through co-fermentation using B. subtilis and L. plantarum

To accelerate GABA production, Bacillus subtilis, which synthesizes various metabolites including hydrolase was selected as a co-fermenting bacterial strain. Yeak (2017) has previously reported that B. subtilis synthesizes pyridoxal phosphate, which acts as a co-factor in the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing). Thus, it can be expected that production of γ-PGA, peptides, and coenzyme during the first alkaline fermentation could enhance GABA production during lactic fermentation with L. plantarum.

The first (alkaline) fermentation was carried out by adding 2% glucose as a nutrient and 5% MSG as a precursor of γ-PGA. During the second (lactic) fermentation, skim milk at concentrations of 0, 1, 3, and 5% was added as a source of vitamins, minerals, and fermentable sugar. Addition of skim milk is intended to support the growth and metabolite production of L. plantarum.

Table 1 shows the changes in pH, acidity, viable cell count, viscosity, and γ-PGA molecular weight after alkaline fermentation using B. subtilis HA. The pH increased from 6.93 to 8.08 after 2 days of fermentation, while the acidity decreased to 0.03%. The viable cell count of B. subtilis HA in the fermented HG increased from 6.01 log CFU/mL to 8.53 log CFU/mL.

Table 1.

Changes in the physicochemical properties of hydroponic ginseng fermented by Bacillus subtilis HA

| (unit: days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Measurement | Fermentation time | ||

|

| |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| pH | 6.93±0.00 | 6.29±0.01 | 8.08±0.01 |

| Acidity (%) | 0.08±0.00 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.03±0.00 |

| Viable cell count (log CFU/mL) | 6.01±0.10 | 6.84±0.48 | 8.53±0.04 |

| Consistency index (Pa·sn) | –1) | 0.15±0.01 | 0.79±0.03 |

| Mucilage content (%) | – | 2.84±0.26 | 2.13±0.41 |

| Tyrosine (mg%) | 7.83±0.01 | 7.90±0.00 | 15.79±0.02 |

| Molecular weight of γ-PGA (Da) | – | 94.82±0.00 | 4,972.71±0.00 |

Values are mean±SD (n=3).

CFU, colony-forming unit; PGA, poly-γ-glutamic acid.

Not detected.

The viscosity increased to 0.79 Pa·sn by production of mucilage, which had a molecular weight of 4,972.71 Da. However, the viscosity of the HG culture broth was lower than that previously reported for extracts from Hovenia dulcis (Yoon et al., 2018). Further, higher HG concentrations resulted in a decreased amount of recovered mucilage (data not shown), suggesting that saponins in the HG may affect the biosynthesis of γ-PGA. Moreover, we found that the molecular weight of biopolymers produced by B. subtilis influenced the viscosity of the fermented product.

The concentrations of peptides derived from ginseng protein and casein were indirectly estimated by the tyrosine content. Proteolytic enzymes were produced during alkaline fermentation, resulting in a slight increase in tyrosine content from 7.83 mg% to 15.79 mg% (Table 1).

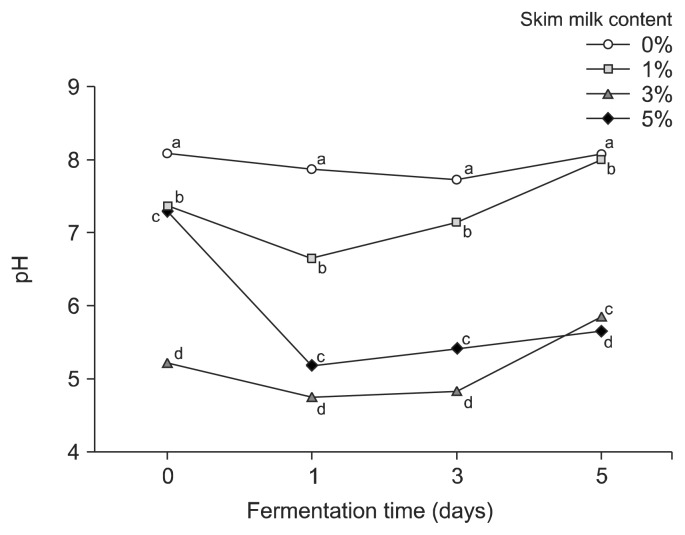

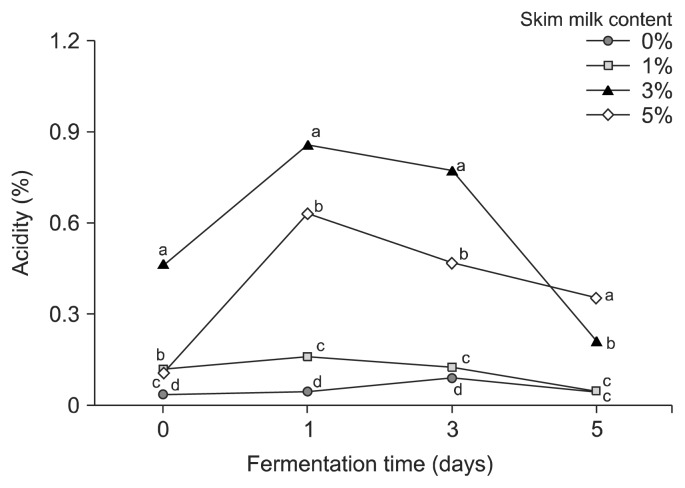

For the second (lactic) fermentation, skim milk was added and L. plantarum EJ2014 was inoculated in the first-fermented broth, which showed a pH of 8.08, an acidity of 0.03%, and viable cell count of B. subtilis HA 8.53 log CFU/mL. The initial pH was in the range of 8.07 (no skim milk) to 7.30 (5% skim milk). After 1 day of fermentation, the pH decreased for all samples; for broth containing 5% skim milk, the pH decreased to 5.18. However, as fermentation progressed, the pH increased, and after 5 days of lactic fermentation, the pH was 8.07 for the control and 5.63 for broth containing 5% skim milk (Fig. 2). In contrast, the acidity of the broth increased at the start of the second fermentation but, after 1 day, it subsequently decreased. The HG culture containing 5% skim milk had an initial acidity of 0.11%; after 1 day of fermentation, to the acidity increased to 0.63%, and then decreased to 0.35% acidity after 5 days of lactic fermentation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of skim milk content on the pH of hydroponic ginseng co-fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014 after fermenting by Bacillus subtilis HA. Each value shows mean±SD (n=3). Different letters (a–d) in the same fermentation time mean a significant difference by Duncan’s multiple range test (P <0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effect of skim milk content on the acidity of hydroponic ginseng co-fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014 after fermenting by Bacillus subtilis HA. Each value shows mean±SD (n=3). Different letters (a–d) in the same fermentation time mean a significant difference by Duncan’s multiple range test (P <0.05).

In a study by Lee et al. (2017), an incubation temperature of 30°C during the lactic fermentation was shown to induce a sharp decrease in pH over 24 h. However, the decrease in pH observed in this study was minimal after 1 day of lactic fermentation. Generally, lactic fermentation leads to a lower pH and increased acidity since fermentable sugars are used to produce lactic acid. However, the decrease in acidity observed during co-fermentation of HG suggests that during GABA production the glutamate precursor is converted to GABA by glutamate decarboxylase, a process that requires a proton, and thus reduces the acidity of the fermented product (Shan et al., 2015). Therefore, the decrease in acidity during lactic fermentation with L. plantarum was correlated to GABA production.

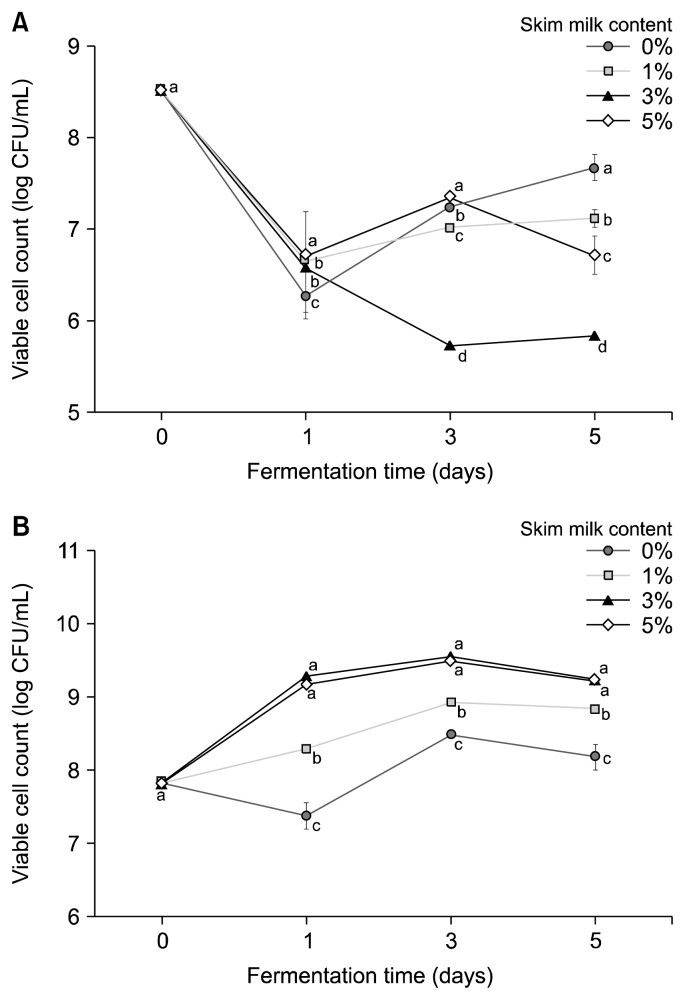

These changes in pH and acidity are similar to those reported by Choi (2017), who showed addition of increased concentrations of skim milk to broth decreases the pH and increases the acidity. After 1 day of lactic fermentation, the viable cell count of B. subtilis decreased from 8.53 log CFU/mL to 6.26~6.70 log CFU/mL, but subsequently increased. However, during the second fermentation the HG culture with 5% skim milk showed a decrease in B. subtilis viable cell count and an increase in L. plantarum, which showed approximately 9 log CFU/mL by the end of the fermentation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of skim milk content on the viable cell count of hydroponic ginseng co-fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014 after fermenting by Bacillus subtilis HA. (A) B. subtilis HA viable cell count, (B) L. plantarum EJ2014 viable cell count. Each value shows mean±SD (n=3). Different letters (a–d) in the same fermentation time mean a significant difference by Duncan’s multiple range test (P <0.05).

TLC analysis of MSG consumption and GABA production showed that the most effective GABA conversion was achieved when the HG broth was fortified with 5% skim milk (Fig. 5). HPLC analysis revealed that the GABA content was 1.03% after the co-fermentation (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) production pattern of hydroponic ginseng co-fermented by Bacillus subtilis HA and Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014. Skim milk (A) 0%, (B) 1.0%, (C) 3.0%, and (D) 5.0%. MSG, monosodium L-glutamate.

Table 2.

GABA conversion from glutamic acid during co-fermentation of hydroponic ginseng by Bacillus subtilis HA and Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014

| (unit: %) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Fermentation type | Concentration | |

|

| ||

| Glutamic acid | GABA | |

| 1st fermentation (B. subtilis) | ||

| Before | 4.02±0.03 | –1) |

| After | 3.75±0.10 | – |

| 2nd fermentation (L. plantarum)2) | ||

| Before | 2.15±0.07 | – |

| After | 0.62±0.03 | 1.03±0.01 |

Values are mean±SD (n=3).

Not detected.

The 2nd lactic acid fermentation was performed with 5.0% skim milk.

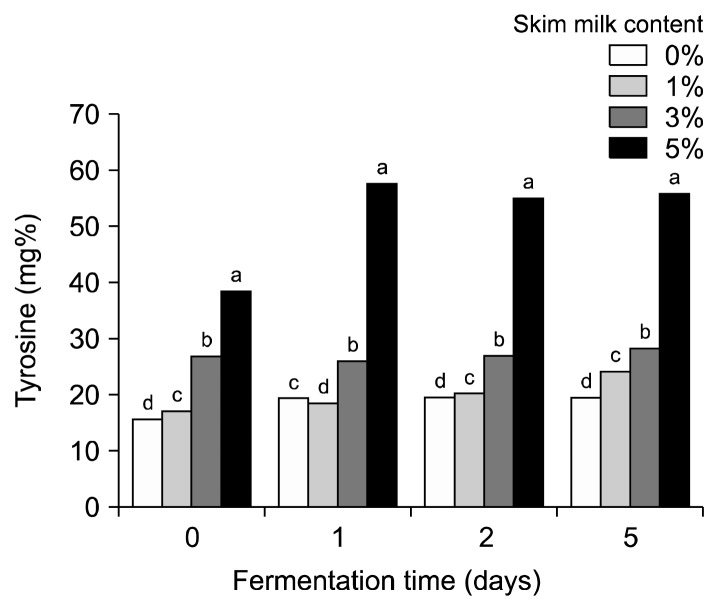

To confirm the presence of products from degradation of casein in the fermented HG products, the peptide content was measured indirectly using a tyrosine standard curve. The tyrosine content increased from 7.83 mg% to 15.79 mg% after 2 days of alkaline fermentation. When skim milk was added, the tyrosine content drastically increased to 16.92, 26.73, and 38.33 mg% for broths with 1, 3, and 5% skim milk, respectively. After 5 days of lactic fermentation, the tyrosine content increased to 55.67 mg% for the HG broth with 5% skim milk (Fig. 6). These results are consistent with the increase in peptides reported during co-fermentation of pumpkin broth enriched with skim milk (Park, 2018). Generally, peptides are reported to have immune-boosting properties (Beaulieu et al., 2007; Luz et al., 2018).

Fig. 6.

Change in tyrosine content on different skim milk concentration of co-fermented hydroponic ginseng by Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014 after fermenting by Bacillus subtilis HA. Each value shows mean±SD (n=3). Different letters (a–d) in the same fermentation time mean a significant difference by Duncan’s multiple range test (P <0.05).

In conclusion, HG co-fermented using B. subtilis and L. plantarum was fortified with functional components including γ-PGA, GABA, peptides, probiotics, and postbiotics. Therefore, co-fermented HG product could be used as a functional ingredient in the development of new foods and cosmetics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, Korea) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Community Business Activation program (P0100600 004 Development of High-value Region Specialized Food and Customized Commercialization for Activating Social Economy).

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Beaulieu J, Dubuc R, Beaudet N, Dupont C, Lemieux P. Immunomodulation by a malleable matrix composed of fermented whey proteins and lactic acid bacteria. J Med Food. 2007;10:67–72. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown AW, Shelp BJ. The metabolism and functions of γ-aminobutyric acid. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1–5. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BY, Cho SC. Preparation of sun-dried salt containing GABA by co-crystallization of fermentation broth and deep sea water. Food Eng Prog. 2015;19:420–426. doi: 10.13050/foodengprog.2015.19.4.420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JW. Master’s thesis. Keimyung University; Daegu, Korea: 2017. Optimized production of poly-γ-glutamic acid and γ-amino butyric acid from Dendropanax morbifera extracts by Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum. [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Park JS, Whang KS, Yoon MH, Choi WY. Production of microbial biopolymer, poly(γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus subtilis BS 62. Agric Chem Biotechnol. 2004;47:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SH. Masters’s thesis. Gyeongsang National University; Gyeongnam, Korea: 2018. Comparison between the essential and non-essential elemental contents of the soil- versus hydroponically-grown strawberries. [Google Scholar]

- Kang SY, Kim ND. The antihypertensive effect of red ginseng saponin and the endothelium-derived vascular relaxation. J Ginseng Sci. 1992;16:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi Y, Sasa H, Kita T, Hirata J, Tode T, Nagata I. Inhibition of human ovarian cancer cell proliferation in vitro by ginsenoside Rh2 and adjuvant effects to cisplatin in vivo. Anticancer Drugs. 1991;2:63–67. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GS, Hyun DY, Kim YO, Lee SE, Kwon H, Cha SW, et al. Investigation of ginsenosides in different parts of Panax ginseng cultured by hydroponics. J Korean Soc Hortic Sci. 2010;28:216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kim GS, Hyun DY, Kim YO, Lee SW, Kim YC, Lee SE, et al. Extraction and preprocessing methods for ginsenosides analysis of Panax ginseng C.A. Mayer. Korean J Med Crop Sci. 2008;16:446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS. Masters’s thesis. Korea National Open University; Seoul, Korea.: 2014. Effect of light quality and intensity on growth and ginsenoside contents of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer by hydroponic cultivation. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Guo Q, Packer L. Free radical scavenging activity of red ginseng aqueous extracts. Toxicology. 2002;172:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kum SJ, Yang SO, Lee SM, Chang PS, Choi YH, Lee JJ, et al. Effects of Aspergillus species inoculation and their enzymatic activities on the formation of volatile components in fermented soybean paste (doenjang) J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:1401–1418. doi: 10.1021/jf5056002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Son JY, Lee SJ, Lee HS, Lee BJ, Choi IS, et al. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum B-134 isolated from makgeolli, traditional Korean rice wine. J Life Sci. 2017;5:567–574. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2017.27.5.567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Qiu T, Huang G, Cao Y. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Lactobacillus brevis NCL912 using fed-batch fermentation. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:85–91. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz C, Izzo L, Graziani G, Gaspari A, Ritieni A, Mañes J, et al. Evaluation of biological and antimicrobial properties of freeze-dried whey fermented by different strains of Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Funct. 2018;9:3688–3697. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00535D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam KY. Clinical applications and efficacy of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) J Ginseng Res. 2002;26:111–131. doi: 10.5142/JGR.2002.26.3.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MH, Chung HY, Yong HS, Kim KW, Chung HY, Oura H, et al. Effects of ginsenoside Rb2 on the antioxidants in SAM-R/1 mice. BMB Reports. 1992;25:492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Oura H, Hiai S. Physiological chemistry of ginseng. Metabolism Disease. 1973;10:564–569. [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ. Master’s thesis. Keimyung University; Daegu, Korea.: 2018. Optimized production of γ-aminobutyric acid and bioactive compounds from old pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) by co-fermentation. [Google Scholar]

- Park KY. Increased health functionality of fermented foods. Food Industry and Nutrition. 2012;17(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Man CX, Han X, Li L, Guo Y, Deng Y, et al. Evaluation of improved γ-aminobutyric acid production in yogurt using Lactobacillus plantarum NDC75017. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:2138–2149. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih IL, Van YT, Chang YN. Application of statistical experimental methods to optimize production of poly(γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus licheniformis CCRC 12826. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2002;31:213–220. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00103-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh VK, Agarwal SS, Gupta BM. Immunomodulatory activity of Panax ginseng extract. Planta Med. 1984;50:462–465. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH. Master’s thesis. University of Seoul; Seoul, Korea: 2014. Effects of growth of strawberry as influenced by red, blue and UV light irradiation under hydroponics. [Google Scholar]

- Tsushida T, Murai T. Conversion of glutamic acid to γ-aminobutyric acid in tea leaves under anaerobic conditions. Agric Biol Chem. 1987;51:2865–2871. [Google Scholar]

- Yeak KYC. Master’s thesis. Georg-August University Göttingen; Goettingen, Germany: 2017. Bacillus subtilis adaptation to the overexpression of a partial heterologous vitamin B6 synthesis pathway. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S, Hiramatsu J, Hayakawa K. Production of γ-aminobutyric acid from alcohol distillery lees by Lactobacillus brevis IFO-12005. J Biosci Bioeng. 2002;93:95–97. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(02)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon WK, Garcia CV, Kim CS, Lee SP. Fortification of mucilage and GABA in Hovenia dulcis extract by co-fermentation with Bacillus subtilis HA and Lactobacillus plantarum EJ2014. Food Sci Technol Res. 2018;24:265–271. doi: 10.3136/fstr.24.265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JT, Qu ZW, Liu Y, Deng HL. Preliminary study on antiamnestic mechanism of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1. Chin Med J. 1990;103:932–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]