Abstract

Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) plays an essential role as a receptor for proteins targeted to mitochondria. TOMM20 was shown to be overexpressed in various cancers. However, the oncological function and therapeutic potential for TOMM20 in cancer remains largely unexplored. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism of TOMM20’s contribution to tumorigenesis and to explore the possibility of its therapeutic potential using colorectal cancer as a model. The results show that TOMM20 overexpression resulted in an increase in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of colorectal cancer (CRC) cells, while siRNA-mediated inhibition of TOMM20 resulted in significant decreases in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. TOMM20 expression directly impacted the mitochondrial function including ATP production and maintenance of membrane potential, which contributed to tumorigenic cellular activities including regulation of S phase cell cycle and apoptosis. TOMM20 was overexpressed in CRC compared to the normal tissues and increased expression of TOMM20 to be associated with malignant characteristics including a higher number of lymph nodes and perineural invasion in CRC. Notably, knockdown of TOMM20 in the xenograft mouse model resulted in a significant reduction of tumor growth. This is the first report demonstrating a relationship between TOMM20 and tumorigenesis in colorectal cancer and providing promising evidence for the potential for TOMM20 to serve as a new therapeutic target of colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Cell cycle, Colorectal cancer, EMT, Mitochondria, TOMM20

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality, and the third most common cancer diagnosed in males and females globally (1). Despite the availability of primary treatment of surgical resection of the tumor, 45% of patients die after treatment because of tumor metastasis (2). Although colonoscopy has been instrumental in screening and early diagnosis of CRC, there is a large number of CRC cases diagnosed at advanced stages (3). Although numerous studies have characterized the molecular pathology of CRC progression, molecular diagnostics and therapies for advanced stages of CRC have not been adequately developed. Thus, it is important to develop biomarkers to facilitate more accurate prognoses and inform novel treatment strategies. These markers would further the field’s understanding of the molecular mechanisms regulating CRC progression.

Recently, cancer metabolism has been the focus of cancer research and has revealed that malignant cells possess normal mitochondrial function (4). Cancer cells were shown to contain increased mitochondrial activity in various human cancers (5, 6) and stable mitochondrial membrane potential has been shown to play an essential role in the development of various cancers (7). Mitochondria have many functions which support cell growth, division, and apoptosis. Important to mitochondrial function is the protein translocation system, requiring many proteins for proper activity. Among the translocation system, one in the outer membrane of mitochondria is the multi-subunit translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex (8). Translocase of Outer Mitochondrial Membrane 20 (TOMM20) is a receptor and a key subunit of the TOM complex and has been reportedly associated with many malignant tumors (9–13). In these cancers, increased expression of TOMM20 has been shown to correlate with increased mitochondrial mass. However, it is not fully elucidated how the expression of TOMM20 contributes to tumor development and progression.

We previously reported that the SNP, rs7930, residing in the 3′ UTR of TOMM20 is associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer (14). In this study, we investigated if TOMM20 was overexpressed in CRC tissues and how it contributed to CRC tumorigenesis. Also, we explored the possibility of suppression of TOMM20 as therapeutic strategy for CRC.

RESULTS

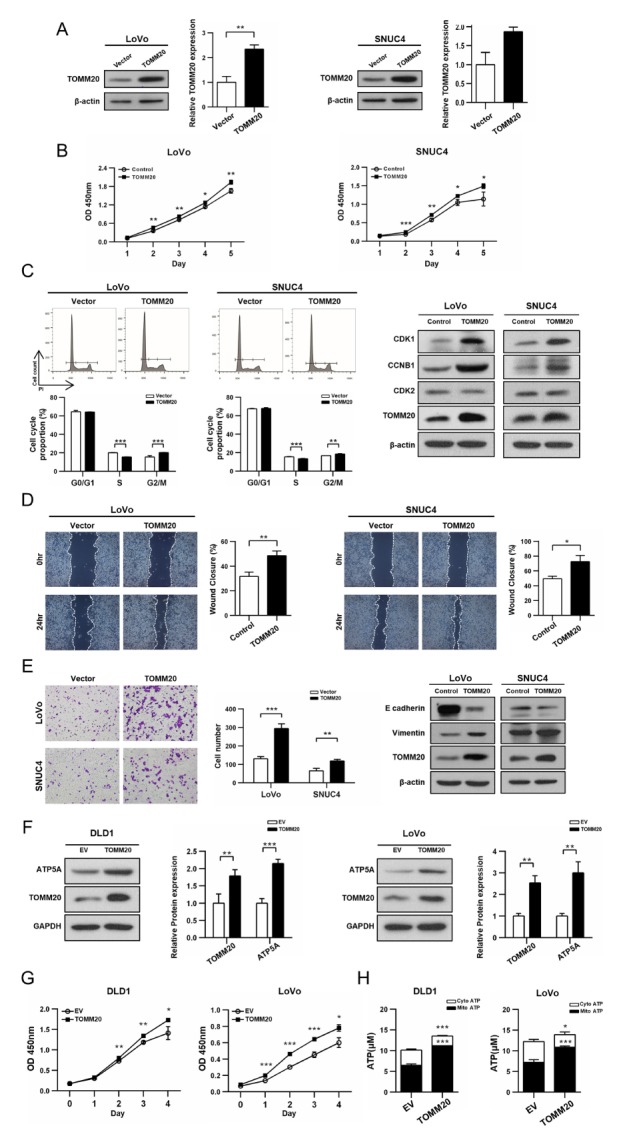

TOMM20 overexpression promoted cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC cells via an increase in mitochondrial ATP synthesis

To delineate the impact of TOMM20 overexpression on CRC tumorigenesis, LoVo and SNUC4 cells were transiently transfected with the full-length TOMM20 cDNA (Fig. 1A). Cells overexpressing TOMM20 exhibited increased proliferation rates compared with the mock transfected controls (Fig. 1B). Because TOMM20 expression affected cell proliferation, the impact of TOMM20 overexpression on the cell cycle was assessed. FACS analysis revealed that cells transfected with TOMM20 cDNA had reduced number of cells in the S phase and increase in the G2/M phase compared to those of the mock transfected cells. Western blot analysis indicated that TOMM20 overexpressing cells had increased expression of Cycle Dependent Kinase 1 (CDK1) and Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), while Cycle Dependent Kinase 2 (CDK2) expression was not significantly affected (Fig. 1C, S1A). Next, we investigated if apoptosis was also affected by TOMM20 expression and FACS analysis revealed that overexpression of TOMM20 did not significantly affect apoptosis compared to negative controls (Fig. S2). Together, increased proliferation of CRC cells following TOMM20 overexpression appears to be the result of changes in the cell cycle rather than apoptosis.

Fig. 1.

TOMM20 overexpression resulted in the increased MitoATP production and promoted proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC cells. (A, B) TOMM20 overexpressing cells showed increased proliferation rate compared to the vector transfected control cells as determined by the CCK-8 assay. (C) Cell cycle distribution by FACS analysis (D) Migration capacity determined by the wound healing assay. (E) Results of matrxigel invasion analysis (F) Cell proliferation in stable cell lines determined by the CCK-8 assay (G) Increase in ATP production by mitochondria -(H) Western blot analysis of total protein extracts showing increased amount of ATP5A. All quantitative results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Additionally, we examined the effect of TOMM20 overexpression on migration and invasion of cells. As shown in Fig. 1D, TOMM20 overexpressing cells displayed more rapid wound closure as their cell migration rate was increased relative to the mock transfected control cells. Invasion capability was determined using the transwell system. The number of cells invading the matrix gel was almost two-fold higher with the TOMM20 cDNA transfected cells compared to the mock transfected cells (Fig. 1E). Western blot analysis of the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers supported significantly increased EMT phenomenon accompanying overexpression of TOMM20. Decreased E-cadherin expression and increased Vimentin expression was shown in TOMM20 cDNA transfected cells compared with mock-transfected control cells (Fig. 1E, S1B). Together, an increased expression of TOMM20 in CRC cells increase; i) cell growth capability and ii) characteristics of aggressiveness of CRC cells.

To characterize the mechanism(s) underlying the phenotype of cancer cells with increased TOMM20 expression, mitochondrial ATP-synthesis activity was examined using stable TOMM20-overexpressing DLD1 and LoVo cell lines established with a Lentiviral vector system. Overexpression of TOMM20 was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 1F). TOMM20-overexpressing cells displayed much higher cell proliferation rates compared to control cells transfected with an empty vector (EV) (Fig. 1G). Mitochondria-produced ATP (MitoATP) was increased to more than 1.5 fold higher level in TOMM20-overpressing cells compared to that of the EV control cells (Fig. 1H). Also, the amount of ATP Synthase Subunit 5 Alpha (ATP5A), increased in TOMM20-overexpressing cells (Fig. 1F), suggesting an increase in the translocation of nuclear encoded mitochondrial protein. These results suggest that TOMM20 overexpressing cells increased MitoATP production, contributing to an increase in cellular growth, and subsequent impact on CRC tumorigenesis.

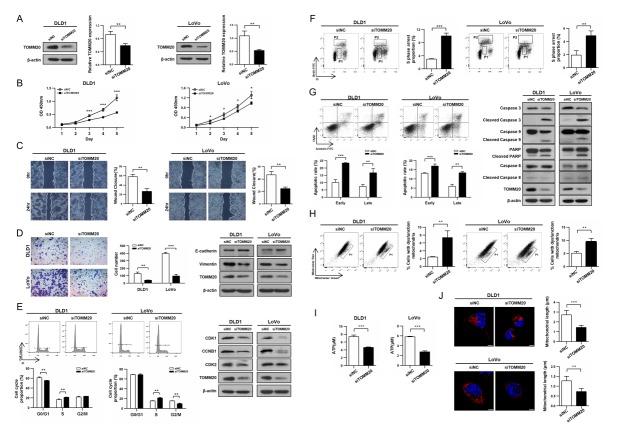

TOMM20 suppression inhibited CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion

To evaluate TOMM20 as a potential target for CRC therapy, we assessed the impact of suppression of TOMM20 expression on CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Treatment with siTOMM20 resulted in reduction of TOMM20 expression in DLD1 and LoVo cells (Fig. 2A) and TOMM20 suppression led to profound reduction of the cell proliferation rate compared to control cells transfected with negative siRNA (siNC) (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the siTOMM20 transfected cells showed significantly retarded migration resulting in reduced closure of the wound compared to control cells (Fig. 2C). The number of cells invading the matrix gel was also markedly reduced to 32% and 25% of the negative control DLD1 and LoVo cells, respectively. Consistent with these findings, the expression of E-cadherin was increased while that of Vimentin decreased in the siTOMM20 transfected cells compared to those of the siNC controls (Fig. 2D, S3A).

Fig. 2.

Reduced expression of TOMM20 diminished characteristics of cancer cells and caused mitochondrial dysfunction in CRC cells. (A, B) siTOMM20 transfection resulted in suppression of TOMM20 expression and stunted cell growth compared to the negative control cells. (C) Reduced migration of CRC cells by suppression of TOMM20 expression. (D) Reduction in invasion of siTOMM20 treated cells and corresponding expressions of E-cadherin and Vimentin. (E) Cell cycle analysis revealed the increased proportion of the S phase cells in siTOMM20 transfected cells. (F) BrdU incorporation experiment showed much increased BrdU-negative S phase cells (P1) in siTOMM20 transfected cells. (G) FACS analysis revealed increased apoptosis in siTOMM20 transfected cells. Western blot analysis revealed increased cleavage activities in siTOMM20 transfected cells. (H) FACS analysis using MitoTracker Green and Red staining showed increase in the number of mitochondria with lost membrane potential (P1). (I) Reduced ATP production in siTOMM20 treated cells. (J) MitoTracker Red staining for live cells and confocal microscopy showed mitochondrial fragmentation in siTOMM20-transfected cells. All quantitative results are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

TOMM20 suppression induced S-phase arrest and apoptosis

To delineate the underlying mechanism(s) of a reduction in cell proliferation following TOMM20 suppression, FACS was applied for cell cycle analysis. For both cell lines, the proportion of the S phase cells was higher following siTOMM20 transfection compared with the siNC transfection and consequently CDK1 and CCNB1 expression decreased in the siTOMM20-transfected cells compared with the siNC-transfected cells (Fig. 2E, S3B).

Since both cell lines exhibited an increase in the proportion of S-phase cells following TOMM20 suppression, we tested if these cells were encountering difficulty in DNA-synthesis. We measured the proportion of cells undergoing DNA synthesis using Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation into newly synthesizing DNA. It was found that the BrdU-positive S phase cells (P2) were reduced, while the BrdU-negative S phase cells (P1) increased in the siTOMM20-transfected cells, compared to those of the siNC-transfected cells (Fig. 2F). This result clearly supports that cells were stalling in the S-phase due to delayed DNA synthesis. To further understand the underlying mechanism of the reduced cell proliferation, apoptosis was investigated. The siTOMM20 transfected cells showed significant increase in early and late phases of apoptosis compared with the siNC transfected cells. In accordance with these results, the cleaved forms of Caspase 3, Caspase 9, and PARP were significantly increased, but that of Caspase 8 was unchanged, indicating that only the intrinsic apoptosis pathway was activated by TOMM20 suppression (Fig. 2G, S3C). Our results revealed that TOMM20 suppression caused the S phase arrest of the cancer cells and induced apoptosis resulting in the significant suppression of cell proliferation.

Suppression of TOMM20 expression resulted in dysfunctional mitochondria

Next, we investigated the effect of TOMM20 down-regulation on mitochondrial function. FACS analysis using MitoTrackcer Green and Red staining revealed that the cells with damaged mitochondria with lost membrane potential were increased to 3 and 1.8 fold in siTOMM20-treated DLD1 and LoVo cells compared with the siNC-treated cells, respectively (Fig. 2H). Additionally, the ATP production in the siTOMM20-transfected cells decreased to approximately 50% of that of the control cells. Also, the amount of ATP5A and COXIV were reduced to less than 40% in the mitochondrial fraction of the siTOMM20-transfected cells compared to that of the siNC-transfected cells, suggesting decrease in translocation of nuclear proteins into mitochondria (Fig. 2I, S4). We also detected the tangled and fragmented forms of mitochondria closely situated in the perinuclear region in the siTOMM20-transfected cells whereas mitochondria in control cells were long and well dispersed in cytoplasm (Fig. 2J). Together, these results showed that inhibition of TOMM20 expression caused mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to S-phase arrest and apoptosis.

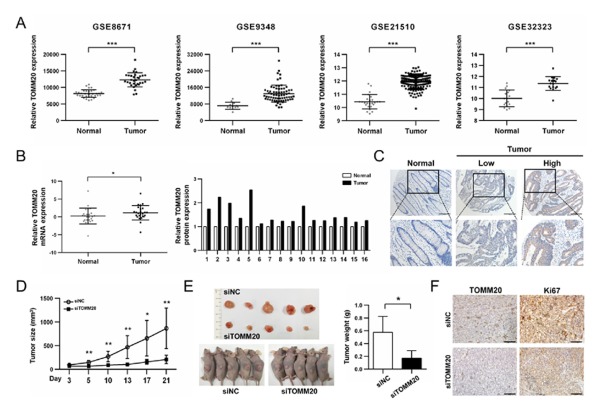

TOMM20 expression is increased in CRC and associated with metastatic characteristics

To investigate TOMM20 expression in CRC, we analyzed gene expression data of GSE21510, GSE9348, GSE32323, and GSE8671. All four datasets revealed much higher expression of TOMM20 mRNA in CRC compared to the normal tissues (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the expression of the TOM complex subunits also increased in cancer tissue compared to the normal tissue in GSE8671 (Fig. S5). We also obtained and performed real-time PCR and western blot analyses to determine the expression of TOMM20 in CRC tissues. From 25 pairs of samples, TOMM20 mRNA expression was increased in CRC tumors compared to the matching adjacent normal tissues. Of 16 pairs of patient tissues, five showed more than 1.5 fold higher TOMM20 expression compared to those of adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 3B). Immunohistochemical analysis also showed increased TOMM20 expression in the vast majority of cancer tissues compared with normal controls (65/73; 89%) as shown in Fig. 3C. Also, 37% of these samples had a score of 4 or greater (i.e., much increased TOMM20 expression).

Fig. 3.

TOMM20 is overexpression in colorectal cancer tissues and Knockdown of TOMM20 suppressed CRC tumor growth in vivo. (A) Analyses of TOMM20 mRNA expression level in GEO data (***P < 0.001). (B) Relative expression of TOMM20 mRNA in 25 CRC patients as assessed by qRT-PCR analysis. The P-value was calculated by the Mann-Whitney test (*P < 0.05). Western blot analysis of TOMM20 was applied in 16 CRC tumor and matching normal tissues. (C) Representative Images of TOMM20 detected by IHC in CRC tissues and the non-tumor tissue. Scale bar = 200 μm. (D) Intratumoral injection of siTOMM20led to stunting of tumor growth (n = 5). (E) Tumor weight at 21 days after siRNA injection (F) TOMM20 and Ki67 expression characterized by immunohistochemical staining of xenografts tumors. Scale bar: 100 μm.

To further investigate the relationship between TOMM20 and CRC tumorigenesis, the association between TOMM20 mRNA expression and clinicopathological parameters was analyzed using the clinical information provided in the GSE103479 dataset. The median value of TOMM20 mRNA expression was used to divide CRC tissues into ‘high’ or ‘low’ expression groups (Table 1). Statistical analysis revealed that the increased expression level of TOMM20 in CRC tissues is significantly associated with various clinicopathological variables. In particular, tumors with 24 or more lymph nodes (P = 0.0013) and perineural invasion (P = 0.0024) were associated with high levels of TOMM20 expression.

Table 1.

Relationship between clinical pathologic characteristics and differential expression of TOMM20 mRNA in GSE103479

| Variables | Patients No | TOMM20 mRNA expression | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Low | High | |||

| Age | 0.5314 | |||

| < 60 | 28 | 12 | 16 | |

| ≥ 60 | 126 | 65 | 61 | |

| Tumor size | 0.7419 | |||

| < 5 cm | 74 | 37 | 37 | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 70 | 33 | 37 | |

| Clinical stage | 0.0287*,a | |||

| IIA | 70 | 32 | 38 | |

| IIB | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| IIC | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| IIIA | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| IIIB | 47 | 27 | 20 | |

| IIIC | 19 | 5 | 14 | |

| pT stage | 0.041*,a | |||

| T1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| T2 | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| T3 | 110 | 55 | 55 | |

| T4 | 39 | 16 | 23 | |

| pN stage | 0.5792a | |||

| N0 | 84 | 40 | 44 | |

| N1 | 50 | 28 | 22 | |

| N2 | 22 | 10 | 12 | |

| lymph nodes (n) | 0.0013**,b | |||

| < 24 | 114 | 66 | 48 | |

| ≥ 24 | 38 | 10 | 28 | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.0024**,b | |||

| No | 99 | 52 | 47 | |

| Yes | 13 | 1 | 12 | |

| Differentiation | 1 | |||

| Poor | 29 | 15 | 14 | |

| Moderate/Well | 123 | 63 | 60 | |

Chi-square test,

Fisher’s exact test,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Inhibition of TOMM20 suppressed tumor growth in a xenograft model mouse

Next, to assess the possibility of TOMM20 suppression as a therapeutic strategy in vivo, we established a xenograft mouse model and intratumoral injection of siTOMM20 was conducted. Compared to siNC-injected tumors, siTOMM20-injected tumors were significantly smaller (Fig. 3D). At the end of three weeks, tumors injected with siTOMM20 weighted significantly less compared to those with injected with siNC, resulting in tumor growth stunting (Fig. 3E). Additionally, immunohistochemistry revealed significant reduction in the expressions of Ki-67 and TOMM20 in the tumors injected with siTOMM20 (Fig. 3F). Together, these results suggest that TOMM20 is a potential new therapeutic target for CRC.

DISCUSSION

Although increased TOMM20 expression was associated with malignancy of various cancers (10–12), it has not been clearly shown how increased expression of TOMM20 contributes to tumorigenesis in various cancers. In this study, we provided evidence that TOMM20 expression upregulated in CRC tissue is related with cell cycle dysregulation causing an increased cell proliferation, as well as with invasiveness of cancer cells. For local invasion, oxidative mitochondrial metabolism at the cellular leading edge was reported to provide necessary ATP surge for cytoskeletal alterations required for motility (15, 16). Also, EMT activation has been shown to favor mitochondrial metabolites such as fumarate and mild elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (17, 18). TOMM20 overexpression resulted in increased production of mitochondrial ATP, which may cause ROS generation. Here we showed EMT activation following increase of TOMM20 expression with a subsequent increase in mobility and invasion capacities of CRC cells. ROS plays either as a signaling molecule for cell proliferation or cytotoxic agent depending on its cellular concentration. Although it was not assessed, ROS production accompanying TOMM20 overexpression in the present experimental system must not be reached to the cytotoxic level so that cells were led to EMT activation not to cell death. Mitochondrial ROS has been reported to cause EMT process through activating the MAP kinase cascades in colorectal cancer cells (19). Nevertheless, in this study, either production of ROS and mitochondrial metabolites has not been assessed. Thus, further study is required to understand the full extent of TOMM20’s contribution in invasive capacity of CRC cells.

S phase arrest has been shown to inhibit cell growth (20, 21). BrdU-incorporation experiments confirmed that siTOMM20-treated cells stalled at the S phase due to a delay in DNA synthesis caused by reduction in ATP synthesis. In addition to cell cycle dysregulation, TOMM20 downregulation induced apoptosis resulting in a decrease in cell proliferation, in part. Intrinsic apoptotic pathway is activated through mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) leading to the release of death signaling proteins such as cytochrome c (22). It is unclear at this time how a reduced expression of TOMM20 causes MOMP. One likely possibility is that a defect in DNA synthesis due to reduced MitoATP gives a signal to the cell and leads to the release of a death signaling proteins. Further analysis is required to understand the mechanism by which TOMM20 suppression activates apoptosis.

Upon TOMM20 suppression, mitochondria became dysfunctional and were concentrated in the perinuclear region, while they are long and well-dispersed in the cytoplasm of the negative control cells. Tumor cell motility and invasion were shown to be associated with increased mitochondrial trafficking, to the cortical cytoskeleton and lamellipodia assembly has been associated with a local ATP surge during cell migration (15, 23). Thus, TOMM20 suppression must prevent cells from proper trafficking of mitochondria, and consequent locomotion mainly caused by reduced ATP synthesis.

For the first time, we demonstrated that siTOMM20 injected directly into a tumor prohibited tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model, providing clear evidence that TOMM20 can be a therapeutic target. Our study results indicate that TOMM20 plays a key role during tumorigenesis, and may be a potential therapeutic target in colorectal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed information is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Construction, production and infection of expression plasmids

To construct the TOMM20 expression plasmid, the coding sequences of TOMM20 was amplified using RT-PCR. The amplified fragment was r cloned into pcDNA3.1 to generate pcDNA3.1/hTOMM20-CDS using EcoRI restriction site. It is also cloned into pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Green Puro. For lentiviral packaging, each recombinant plasmid was used for transfection with the psPAX2 and pMD2G into HEK-293T cells (24). Cells were cultured and the virus was harvested at 48 hours and 72 hours post transfection and mixed with PEG-8000. The lentiviral particles were added to culture medium and the clones of efficiently transduced cells were selected by treatment with 5 μg/ml puromycin for two weeks. The sequences for oligonucleotides used for cloning are as follows in Table S1.

Measurement of mitochondrial potential and mass

Cells were incubated with MitoTracker Green (100 nM) and CMXROS (100 nM) for 10 minutes at RT. Stained cells were collected by trypsinization followed by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS containing 2% BSA. Stained cells were analyzed using a BD FACS system (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Xenograft mouse model and analysis of tumor growth

Mice were maintained under standard condition and cared for according to the institutional guidelines for animal care. The animal studies were conducted following the procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in the School of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea (Approval number 2016-0118-03). Five-week old male immuno-deficient BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Orient Bio (Seoul, Korea). The xenograft mouse model was established by subcutaneous injection of 3 × 106 LoVo cells mixed with Matrix gel (Corning) at 1:1 ratio, into left and right flanks of the mice. Three days after injection, each siRNA was intratumorally injected, twice weekly for three weeks. Total of 50 μl containing 1 μg of siRNA mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 and 5% D-glucose in PBS was injected into each flank. Tumor formation was monitored by measuring the tumor with electronic calipers after each injection of siRNA. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: v (mm3) = (a2 × b) / 2, where ‘a’ is the shortest diameter and ‘b’ the longest. Mice were sacrificed 21 days after the initial injection, tumors were harvested, and tumor weights recorded. Tumor formation was determined using five mice.

Statistical analysis

All experiments with cells were repeated at least three times. The P-value was determined using Student’s t-tests and a value of P < 0.05 was statistically significant. TOMM20 expression and clinicopathologic features of colorectal cancer patients were analyzed using Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad software version 6.00 (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, USA).

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2018R1A2B6003455).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devetzi M, Kosmidou V, Vlassi M, et al. Death receptor 5 (DR5) and a 5-gene apoptotic biomarker panel with significant differential diagnostic potential in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36532. doi: 10.1038/srep36532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsouma A, Aggeli C, Lembessis P, et al. Multiplex RT-PCR-based detections of CEA, CK20 and EGFR in colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5965–5974. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism in cancer metastasis: visualizing tumor cell mitochondria and the “reverse Warburg effect” in positive lymph node tissue. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1445–1454. doi: 10.4161/cc.19841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini DM. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell. 2015;162:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilde L, Roche M, Domingo-Vidal M, et al. Metabolic coupling and the Reverse Warburg Effect in cancer: Implications for novel biomarker and anticancer agent development. Semin Oncol. 2017;44:198–203. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schieber M, Chandel NS. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chacinska A, Koehler CM, Milenkovic D, Lithgow T, Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138:628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wise DR, Ward PS, Shay JE, et al. Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase-dependent carboxylation of alpha-ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19611–19616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117773108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curry JM, Tuluc M, Whitaker-Menezes D, et al. Cancer metabolism, stemness and tumor recurrence: MCT1 and MCT4 are functional biomarkers of metabolic symbiosis in head and neck cancer. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1371–1384. doi: 10.4161/cc.24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Han F, He Y, et al. Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in gastric cancer: stromal MCT4 and mitochondrial TOMM20 as poor prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curry JM, Tassone P, Cotzia P, et al. Multicompartment metabolism in papillary thyroid cancer. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2410–2418. doi: 10.1002/lary.25799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikkilineni L, Whitaker-Menezes D, Domingo-Vidal M, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma: A complex metabolic ecosystem with glycolytic reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment. Semin Oncol. 2017;44:218–225. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AR, Park J, Jung KJ, Jee SH, Kim-Yoon S. Genetic variation rs7930 in the miR-4273-5p target site is associated with a risk of colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6885–6895. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S108787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caino MC, Ghosh JC, Chae YC, et al. PI3K therapy reprograms mitochondrial trafficking to fuel tumor cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8638–8643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500722112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivadeneira DB, Caino MC, Seo JH, et al. Survivin promotes oxidative phosphorylation, subcellular mitochondrial repositioning, and tumor cell invasion. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra80. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porporato PE, Payen VL, Perez-Escuredo J, et al. A mitochondrial switch promotes tumor metastasis. Cell Rep. 2014;8:754–766. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sciacovelli M, Goncalves E, Johnson TI, et al. Fumarate is an epigenetic modifier that elicits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Nature. 2016;537:544–547. doi: 10.1038/nature19353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Shao L, Pan C, et al. Elevated level of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species via fatty acid beta-oxidation in cancer stem cells promotes cancer metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:175. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Yu H, Han F, Wang M, Luo Y, Guo X. Biochanin A Induces S Phase Arrest and Apoptosis in Lung Cancer Cells. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018;3545376 doi: 10.1155/2018/3545376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Wen X, Liu N, et al. Epigenetic mediated zinc finger protein 671 downregulation promotes cell proliferation and tumorigenicity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by inhibiting cell cycle arrest. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:147. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li MX, Dewson G. Mitochondria and apoptosis: emerging concepts. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:42. doi: 10.12703/P7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki R, Hotta K, Oka K. Spatiotemporal quantification of subcellular ATP levels in a single HeLa cell during changes in morphology. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16874. doi: 10.1038/srep16874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen GQ, Benthani FA, Wu J, Liang D, Bian ZX, Jiang X. Artemisinin compounds sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis by regulating iron homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0352-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.