Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the associations of high awake blood pressure (BP), high asleep BP, and non-dipping BP, determined by ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), with left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) and geometry.

Methods:

Black and white participants (n=687) in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study underwent 24-hour ABPM and echocardiography at the Year 30 Exam in 2015–2016. The prevalence and prevalence ratios (PR) of LVH were calculated for high awake systolic BP (≥ 130 mmHg), high asleep systolic BP (≥ 110 mmHg), the cross-classification of high awake and asleep systolic BP, and non-dipping systolic BP (percentage decline in awake-to-asleep systolic BP < 10%). Odds ratios (ORs) for abnormal LV geometry associated with these phenotypes were calculated.

Results:

Overall, 46.0% and 49.1% of study participants had high awake and asleep systolic BP, respectively, and 31.1% had non-dipping systolic BP. After adjustment for demographics and clinical characteristics, high awake systolic BP was associated with a PR for LVH of 2.79, (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.63–4.79). High asleep systolic BP was also associated with a PR for LVH of 2.19 (95% CI 1.25–3.83). There was no evidence of an association between non-dipping systolic BP and LVH (PR 0.70, 95% CI 0.44–1.12). High awake systolic BP with or without high asleep systolic BP was associated with a higher OR of concentric remodeling and hypertrophy.

Conclusion:

Awake and asleep systolic BP, but not the decline in awake-to-asleep systolic BP, were associated with increased prevalence of cardiac end-organ damage.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, non-dipping blood pressure, target organ damage, left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular remodeling

Condensed Abstract

In a cross-sectional analysis of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study, we examined the associations of high awake blood pressure (BP), high asleep BP, and non-dipping BP with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and geometry. High awake systolic BP and high asleep systolic BP were associated with a higher prevalence of LVH after multivariable adjustment. There was no evidence of an association between non-dipping systolic BP and LVH. High awake systolic BP was also associated with concentric remodeling and hypertrophy.

Hypertension is highly prevalent and a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1,2]. One mechanism through which high blood pressure (BP) increases the risk for CVD is via the development of alterations in cardiac structure including increases in left ventricular (LV) mass which can lead to LV hypertrophy (LVH), and abnormal LV geometry. Increased LV mass, LVH, and abnormal LV geometry are associated with the development of CVD events including heart failure, and an increased risk of mortality [3–7].

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) measures BP over a 24-hour period, enabling the evaluation of BP while awake and asleep [8]. High awake BP and high asleep BP are each associated with an increased risk for CVD events [9–12]. ABPM can also assess the diurnal pattern of BP. For most adults, BP is higher while awake versus during sleep [13]. The decrease in BP from being awake to asleep period is referred to as BP dipping. Non-dipping BP is defined as a reduction of less than 10% in mean BP while asleep compared to awake [14]. The association between non-dipping BP and a higher prevalence of LVH has been reported in some, but not all, studies [15–18].

In this study, we examined whether high awake BP and high asleep BP, and non-dipping BP were associated with LV mass and LVH, and secondarily abnormal LV geometry in whites and blacks from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study.

METHODS

Study Population

CARDIA is a prospective cohort study sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the US National Institutes of Health and was designed to examine the development of CVD and its risk factors. In 1985–1986, 5,115 black and white men and women were enrolled at four field centers in the United States (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA). Participants were 18 to 30 years of age at baseline, and 70–90% of the surviving participants subsequently completed up to eight follow-up examinations. The details of these examinations have been previously described [19,20]. Institutional review boards from each field center and the CARDIA Coordinating Center approved the study and its components, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants at each examination.

The present investigation is a cross-sectional analysis of the 825 CARDIA participants from the Birmingham and Chicago Field Centers who underwent ABPM as part of an ancillary study following the Year 30 Exam in 2015–2016. Of the 781 participants with a complete ABPM recording (defined below), we excluded 54 participants with transthoracic echocardiograms that were insufficient for analysis and 20 participants who had a prior adjudicated CVD event, defined as having definite or probable myocardial infarction and/or definite decompensated heart failure or chronic stable heart failure, that could affect cardiac structure. Participants (n=20) who had incomplete covariate data were also excluded. After these exclusion criteria were applied, data from 687 participants were included in the analysis.

Data Collection

Data on self-reported age, sex, and race were collected by questionnaire at the baseline CARDIA Exam and confirmed at the Year 2 Exam. The remaining data used in this analysis were collected at the Year 30 Exam. Information on education, smoking status, alcohol intake and antihypertensive medication use were determined by self-report. Physical activity over the past year was assessed in exercise units using the validated CARDIA Physical Activity questionnaire [21]. Height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured from a plasma sample. Glucose and creatinine were measured from a fasting serum sample collected during the study examination. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology equation [22]. Using a spot urine sample collected during the study visit, albuminuria was defined as a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g. Diabetes was defined as a fasting serum glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL or the use of glucose-lowering medications.

Clinic BP Measurement and ABPM

Clinic systolic and diastolic BP were measured at the Year 30 Exam by trained and certified staff following standardized protocols. Briefly, following 5 minutes of rest in the seated position, BP was measured on the right upper arm using an Omron HEM 907XL device (Kyoto, Japan) [23] and an appropriately sized cuff. Three BP measurements were obtained with at least one minute separating each reading. Clinic BP was defined as the mean of the second and third readings. ABPM was conducted over a 24-hour period following the Year 30 Exam using an OnTrak 90227 monitor (Spacelabs, Snoqualmie, WA) with an appropriately sized cuff on the non-dominant arm. Systolic and diastolic BP were measured every 30 minutes. Awake and asleep periods were defined using actigraphy data from an Actiwatch activity monitor (Philips Respironics, Andover, MA) worn on the wrist throughout the same 24-hour period of ABPM supplemented by self-reports of when the participant went to sleep and awakened. To be eligible for the current analysis, participants were required to have a complete ABPM recording, defined as 10 or more valid awake BP readings and 5 or more valid asleep BP readings [24]. Awake and asleep systolic and diastolic BP were each defined based on the mean of all available readings during the respective time periods. Dipping was defined as the percentage difference in mean systolic and diastolic BP, separately, between the awake and asleep periods. Non-dipping systolic and diastolic BP patterns were defined as a percentage dipping < 10% [25]. As recommended by the 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC) / American Heart Association (AHA) BP guideline, high awake systolic and diastolic BP were defined as ≥ 130 mm Hg and ≥ 80 mm Hg, respectively, and high asleep systolic and diastolic BP were defined as ≥ 110 mm Hg and ≥ 65 mm Hg respectively [2]. In a sensitivity analysis, we used the 2018 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/ European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guideline and defined high awake systolic and diastolic BP as ≥ 135 mm Hg and ≥ 85 mm Hg, respectively, and high asleep systolic and diastolic BP as ≥ 120 mm Hg and ≥ 70 mm Hg, respectively [26]. Heart rate was defined using the mean of the readings (mean 24-hour heart rate) from the ABPM.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiograms were acquired at the Year 30 Exam on identically configured Toshiba systems at the two CARDIA field centers using a standardized protocol [27]. Images were obtained in the parasternal long- and short-axis and apical 2- and 4-chamber views. Primary measures of LV dimensions, volumes, and wall thickness were made in triplicate in accordance with the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) [28].

LV mass was calculated from LV end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), septal wall thickness (SWT), and posterior wall thickness (PWT) in diastole. LV mass was indexed to body surface area (BSA) to derive LV mass index (LVMI). Relative wall thickness was calculated as (2*PWT) divided by LVEDD. LVH was defined as LVMI >95 g/m2 in women and >115 g/m2 in men [28]. LV geometry categories were classified as follows: normal geometry (relative wall thickness ≤ 0.42 and no LVH), concentric remodeling (relative wall thickness > 0.42 and no LVH), concentric hypertrophy (relative wall thickness > 0.42 and LVH) or eccentric hypertrophy (relative wall thickness ≤ 0.42 and LVH).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the analytical sample were calculated by high awake systolic BP status, high asleep systolic BP status, and non-dipping systolic BP status, separately. Cubic splines with knots placed at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles were applied to illustrate the unadjusted associations of awake systolic BP, asleep systolic BP, and percent dipping in systolic BP with LVMI. Wald tests were used to assess the statistical significance of the overall associations and whether the associations deviated from being linear. Prevalence and prevalence ratios (PR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of LVH were calculated for high versus not high awake systolic BP, high versus not high asleep systolic BP, and non-dipping versus dipping systolic BP. PRs were calculated in unadjusted and adjusted modified Poisson regression models.[29] Model 1 included adjustment for age at Y30 exam, sex, race, CARDIA field center, 24 hour mean heart rate, and BMI. Model 2 included adjustment for the variables in Model 1 plus diabetes, education level, alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2, albuminuria, and antihypertensive medication use. Model 3 included adjustment for the variables in Model 2 and asleep systolic BP when awake systolic BP was the independent variable and awake systolic BP when asleep systolic BP was the independent variable.

The mean percent decline in systolic BP from awake-to-asleep periods was calculated within categories defined by the cross-classification of high awake systolic BP status and high asleep systolic BP status: without high awake or asleep systolic BP, with high awake systolic BP but not high asleep systolic BP, with high asleep systolic BP but not high awake systolic BP, and with both high awake and high asleep systolic BP. The PR (95% CI) of LVH was calculated for participants with high awake systolic BP but not high asleep systolic BP, high asleep systolic BP but not high awake systolic BP, and both high awake and asleep systolic BP, each compared to participants without high systolic awake BP or high asleep systolic BP (the referent category) in unadjusted and adjusted models. Adjustment was performed as described for Models 1 and 2 above.

Cubic splines were applied to illustrate the unadjusted associations of awake systolic BP, asleep systolic BP, and percent dipping in systolic BP with relative wall thickness. Wald tests were used to assess the statistical significance of the overall associations and whether the associations deviated from being linear. The odds ratios (ORs) (95% CI) of concentric remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, and eccentric hypertrophy versus normal geometry were calculated in categories defined by the cross-classification of high awake systolic BP status with high asleep systolic BP status in unadjusted and adjusted multinomial logistic regression models. Adjustment was performed as described for Models 1 and 2 above.

Potential interaction effects of race and sex, separately, with high awake systolic BP, high asleep systolic BP, and non-dipping systolic BP on LVH and LV geometry were assessed using multiplicative interaction terms (e.g., race*non-dipping systolic BP). In a sensitivity analysis, all primary analyses were repeated using the awake and asleep BP thresholds defined in the 2018 ESC/ESH guideline. Analyses were performed using R Version 3.5.1. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, 46.0% of study participants had high awake systolic BP, 49.1% had high asleep systolic BP and 31.1% had non-dipping systolic BP. Participants with high awake systolic BP, high asleep systolic BP, and a non-dipping systolic BP pattern were more likely to be black, have diabetes and albuminuria, and to be taking antihypertensive medication (Table 1). Also, mean BMI was higher among participants with versus without high awake systolic BP, high asleep systolic BP, and a non-dipping systolic BP pattern.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with and without high awake systolic blood pressure, asleep systolic blood pressure, and non-dipping systolic blood pressure.

| Overall n=687 |

Awake Systolic BP‡ | Asleep Systolic BP† | Non-dipping Systolic BP* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 130 mm Hg (n =371) |

≥ 130 mm Hg (n = 316) |

< 110 mm Hg (n = 350) |

≥ 110 mm Hg (n = 337) |

No (n = 473) |

Yes (n = 214) |

||

| Age, years | 54.7 (3.7) | 54.5 (3.8) | 55.0 (3.7) | 54.5 (3.7) | 54.9 (3.8) | 54.6 (3.7) | 55.0 (3.8) |

| Female | 59.5% | 65.0% | 53.2% | 64.6% | 54.3% | 59.0% | 60.7% |

| Birmingham Field Center | 58.8% | 58.8% | 58.9% | 55.7% | 62.0% | 57.5% | 61.7% |

| Black | 62.7% | 55.5% | 71.2% | 50.0% | 76.0% | 56.0% | 77.6% |

| Education, years | 14.8 (2.6) | 14.9 (2.7) | 14.7 (2.5) | 15.1 (2.7) | 14.5 (2.5) | 15.1 (2.6) | 14.3 (2.4) |

| Current Smoker | 16.2% | 12.7% | 20.3% | 15.1% | 17.2% | 15.4% | 17.8% |

| Alcohol Intake** | |||||||

| None | 52.8% | 51.8% | 54.1% | 49.7% | 56.1% | 49.5% | 60.3% |

| Moderate | 35.8% | 38.3% | 32.9% | 38.3% | 33.2% | 38.5% | 29.9% |

| Heavy | 11.4% | 10.0% | 13.0% | 12.0% | 10.7% | 12.1% | 9.8% |

| Physical Activity | |||||||

| Low | 28.5% | 27.8% | 29.4% | 24.9% | 32.3% | 27.5% | 30.8% |

| Moderate | 37.7% | 36.1% | 39.6% | 39.4% | 35.9% | 37.2% | 38.8% |

| High | 33.8% | 36.1% | 31.0% | 35.7% | 31.8% | 35.3% | 30.4% |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.2 (6.9) | 30.5 (7.0) | 32.1 (6.7) | 29.6 (6.5) | 32.9 (6.9) | 30.5 (6.7) | 32.7 (7.0) |

| Diabetes | 15.6% | 17.7% | 11.1% | 22.3% | 12.7% | 25.2% | |

| Mean 24-hour Heart Rate, bpm | 76.5 (10.1) | 76.0 (9.9) | 77.2 (10.4) | 75.5 (10.0) | 77.6 (10.2) | 76.3 (10.1) | 77.1 (10.1) |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 3.6% | 4.9% | 2.2% | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.6% | 3.7% |

| ACR > 30 mg/g | 8.0% | 3.5% | 13.3% | 3.7% | 12.5% | 6.3% | 11.7% |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 38.3% | 31.8% | 45.9% | 31.4% | 45.4% | 34.2% | 47.2% |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | |||||||

| Clinic | 122.0 (17.3) | 112.9 (12.4) | 131.8 (16.6) | 113.9 (14.3) | 129.6 (16.4) | 121.4 (17.0) | 122.1 (17.9) |

| Awake | 130.0 (15.1) | 118.9 (7.6) | 142.6 (11.0) | 121.7 (11.1) | 138.3 (14.0) | 130.5 (15.1) | 128.3 (14.8) |

| Asleep | 112.0 (15.3) | 103.9 (10.1) | 121.9 (14.6) | 100.3 (6.6) | 124.6 (11.4) | 107.7 (13.2) | 122.1 (14.9) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | |||||||

| Clinic | 74.5 (10.9) | 69.9 (8.9) | 79.9 (10.6) | 70.0 (9.7) | 79.1 (10.2) | 74.3 (10.9) | 74.9 (11.0) |

| Awake | 80.9 (9.1) | 76.0 (6.5) | 86.7 (8.2) | 77.4 (7.8) | 84.5 (9.0) | 81.5 (8.9) | 79.5 (9.3) |

| Asleep | 67.0 (9.3) | 63.3 (7.3) | 71.3 (9.6) | 61.0 (6.0) | 73.2 (8.0) | 64.5 (8.3) | 72.3 (9.1) |

Numbers are mean (SD) or percentage.

Awake systolic BP: mean of systolic blood pressure measurements while awake.

Asleep systolic BP: mean of systolic blood pressure measurements while asleep.

Non-dipping systolic BP was defined as a percentage dip in systolic BP < 10%.

Moderate alcohol intake: 1–14 drinks / week for males, 1–7 for females; Heavy alcohol intake: >14+ drinks / week for males, >7 for females.

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR = albumin to creatinine ratio.

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR = albumin to creatinine ratio.

Associations of Awake, Asleep, and Non-dipping Systolic BP with LVMI and LVH

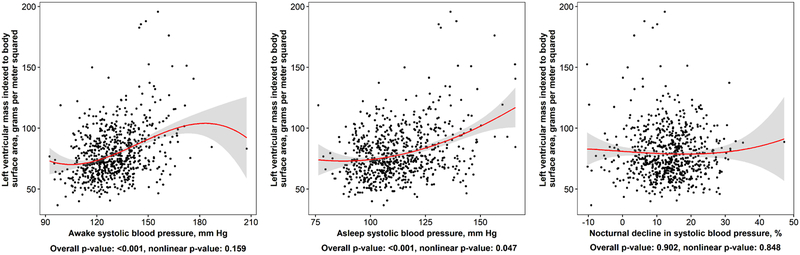

Higher levels of awake and asleep systolic BP, but not systolic BP dipping, were each associated with higher LVMI (Figure 1). The prevalence of LVH was higher among participants with versus without high awake systolic BP in an unadjusted model and after each level of adjustment (Table 2). The prevalence of LVH was higher among participants with versus without high asleep systolic BP in an unadjusted model and after adjustment for age, sex, race, CARDIA field center, 24 hour mean ambulatory heart rate, body mass index, diabetes, education, alcohol intake, smoking status, physical activity, eGFR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio and antihypertensive medication use. This association was attenuated after further adjustment for awake systolic BP (PR 1.15 [95% CI 0.64, 2.07; p=0.645]). There was no evidence of association between non-dipping systolic BP and LVH.

Figure 1: Associations of awake, asleep, and percent dipping in systolic blood pressure with left ventricular mass index.

Points in the figure represent individual-level data in the current analysis. Smoothed red curves show the population-level estimate of the relation of awake or asleep systolic blood pressure with left ventricular mass index. Grey regions around the smoothed red curves are 95% confidence intervals for the mean left ventricular mass index at the given value of awake, asleep systolic blood pressure and percent dip in systolic blood pressure. P-values correspond to tests of overall and nonlinear association between left ventricular mass index and each ABPM measure, separately.

Table 2:

Prevalence ratios for left ventricular hypertrophy among participants with versus without high awake systolic blood pressure, high asleep systolic blood pressure, and non-dipping systolic blood pressure.

| Prevalence Ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awake SBP ≥ 130 versus < 130 mm Hg | P-value | Asleep SBP ≥ 110 versus < 110 mm Hg | P-value | Non-dipping versus dipping SBP | P-value | |

| Prevalence | 16.5% vs. 4.6% | - | 15.1% vs. 5.1% | - | 9.8% vs. 10.1% | - |

| Unadjusted | 3.59 (2.12, 6.08) | < 0.001 | 2.94 (1.76, 4.93) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.59, 1.57) | 0.892 |

| Model 1 | 3.35 (1.96, 5.72) | < 0.001 | 2.53 (1.47, 4.33) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.48, 1.26) | 0.311 |

| Model 2 | 2.79 (1.62, 4.80) | < 0.001 | 2.18 (1.24, 3.83) | 0.007 | 0.70 (0.44, 1.12) | 0.135 |

| Model 3 | 1.86 (1.01, 3.41) | 0.046 | 1.15 (0.64, 2.07) | 0.645 | -- | -- |

Left ventricular hypertrophy based on left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area: left ventricular mass index > 95 g/m2 for females, > 115 g/m2 for males

Model 1 includes adjustment for age, sex, race, CARDIA field center, mean 24-hour heart rate, and body mass index;

Model 2 includes adjustment for variables in Model 1 plus diabetes, education, alcohol intake, smoking status, physical activity, estimated glomerular filtration rate, albumin to creatinine ratio and antihypertensive medication use;

Model 3 includes adjustment for variables in Model 2 plus additional adjustment for awake systolic blood pressure when examining asleep systolic blood pressure as the independent variable, or additional adjustment for asleep systolic blood pressure when examining awake systolic blood pressure as the independent variable.

Abbreviations: SBP = systolic blood pressure

Associations of Categories Defined by the Cross-classification of High Awake Systolic BP and High Asleep Systolic BP with LVH

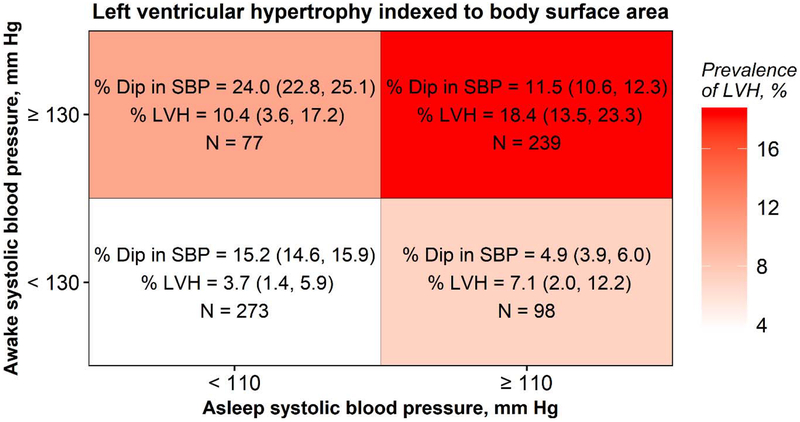

The prevalence of LVH was 3.7%, among participants without high awake or asleep systolic BP, 10.4 % with high awake systolic BP but not high asleep systolic BP, 7.1% with high asleep systolic BP but not high awake systolic BP, and 18.4% with high awake and high asleep systolic BP (Figure 2). The systolic BP dipped by 15.2%, 24.0%, 4.9%, and 11.5% in these four groups, respectively. High awake systolic BP, either with or without high asleep systolic BP, was associated with a higher PR of LVH in the adjusted models (Table 3).

Figure 2: Percent dipping in systolic blood pressure dip and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy* associated with categories of high awake systolic blood pressure status cross-classified by categories of high asleep systolic blood pressure status.

All values for % Dip and % LVH are presented as mean (95% CI)

*Left ventricular hypertrophy based on left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area: left ventricular mass index > 95 g/m2 for females, > 115 g/m2 for males

Abbreviations: LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy; PR = prevalence ratio; % dip in SBP = percentage awake-to-asleep systolic blood pressure dip

Table 3:

Prevalence ratios for left ventricular hypertrophy* among participants with versus without high awake systolic blood pressure cross-classified by high asleep systolic blood pressure.

| Awake SBP < 130 mm Hg | Awake SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asleep SBP < 110 mm Hg (n = 273) |

Asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg (n = 98) |

Asleep SBP < 110 mm Hg (n = 77) |

Asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg (n = 239) |

|

| Prevalence ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1 (ref) | 1.95 (0.76, 4.98) | 2.84 (1.16, 6.94) | 5.03 (2.59, 9.77) |

| Model 1 | 1 (ref) | 1.63 (0.65, 4.10) | 2.80 (1.15, 6.82) | 4.43 (2.24, 8.75) |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref) | 1.61 (0.63, 4.09) | 2.52 (1.04, 6.11) | 3.62 (1.79, 7.29) |

Left ventricular hypertrophy based on left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area: left ventricular mass index > 95 g/m2 for females, > 115 g/m2 for males

Model 1 includes adjustment for age, sex, race, CARDIA field center, mean 24-hour heart rate, and body mass index;

Model 2 includes Model 1 covariates plus additional adjustment for diabetes, education, alcohol intake, smoking status, physical activity, estimated glomerular filtration rate, albumin to creatinine ratio and antihypertensive medication use.

Abbreviation: SBP = systolic blood pressure

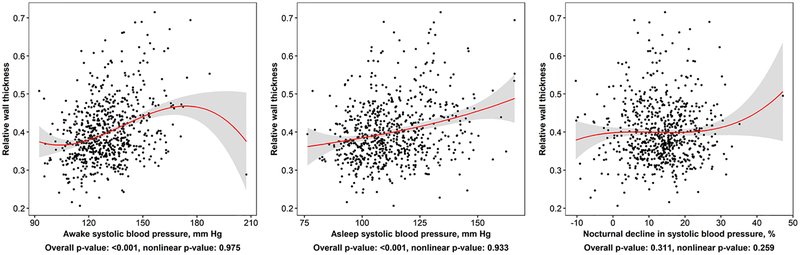

Associations of Awake, Asleep, and Non-dipping Systolic BP with Abnormal LV Geometry

Higher levels of both awake and asleep systolic BP, but not percent dipping in systolic BP, were associated with an increased relative wall thickness (Figure 3). Overall, 62.3% of participants had normal LV geometry, 27.5% had concentric remodeling, 7.0% had concentric hypertrophy, and 3.1% had eccentric hypertrophy. In adjusted models, participants with high awake systolic BP but not high asleep systolic BP and both high awake and high asleep systolic BP had increased odds for concentric remodeling and concentric hypertrophy versus normal geometry relative to those with neither high awake nor high asleep systolic BP (Table 4). In adjusted models, participants with both high awake and high asleep systolic BP had increased odds for eccentric hypertrophy versus normal geometry relative to those with neither high awake nor high asleep systolic BP thresholds.

Figure 3: Associations of awake, asleep, and percent dipping in systolic blood pressure with relative wall thickness.

Points in the figure represent individual-level data in the current analysis. Smoothed red curves show the population-level estimate of the relation of awake or asleep systolic blood pressure with relative wall thickness. Grey regions around the smoothed red curves are 95% confidence intervals for the mean relative wall thickness at the given value of awake or asleep systolic blood pressure and percent dip in systolic blood pressure. P-values correspond to tests of overall and nonlinear association between relative wall thickness and each ABPM measure, separately.

Table 4:

Odds ratios for abnormal left ventricular geometry comparing participants with high awake systolic blood pressure cross-classified by high asleep systolic BP.

| Awake SBP < 130 mm Hg | Awake SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asleep SBP < 110 mm Hg (n = 273) |

Asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg (n = 98) |

Asleep SBP < 110 mm Hg (n = 77) |

Asleep SBP ≥ 110 mm Hg (n = 239) |

|

| Concentric Remodeling | ||||

| Prevalence, % | 22.8 | 29.7 | 39.1 | 38.5 |

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of Concentric Remodeling Versus Normal Geometry | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.43 (0.84, 2.43) | 2.18 (1.24, 3.82) | 2.11 (1.41, 3.18) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.36 (0.78, 2.36) | 2.16 (1.22, 3.81) | 1.94 (1.26, 2.99) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.38 (0.79, 2.43) | 2.02 (1.13, 3.63) | 1.78 (1.14, 2.78) |

| Concentric Hypertrophy | ||||

| Prevalence, % | 1.9 | 7.2 | 14.3 | 21.1 |

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of Concentric Hypertrophy Versus Normal Geometry | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 3.96 (1.03, 15.21) | 8.46 (2.37, 30.20) | 13.53 (4.67, 39.21) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 3.12 (0.79, 12.28) | 8.31 (2.31, 29.93) | 11.32 (3.80, 33.75) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 3.09 (0.74, 12.92) | 7.22 (1.90, 27.50) | 8.45 (2.68, 26.61) |

| Eccentric Hypertrophy | ||||

| Prevalence, % | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 9.1 |

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of Eccentric Hypertrophy Versus Normal Geometry | ||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (ref) | 1.06 (0.21, 5.37) | 0.81 (0.09, 6.87) | 3.38 (1.24, 9.25) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.89 (0.17, 4.69) | 0.83 (0.10, 7.15) | 3.10 (1.07, 8.96) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.85 (0.15, 4.74) | 0.82 (0.09, 7.34) | 3.13 (1.02, 9.60) |

Outcomes: Concentric Remodeling: relative wall thickness > 0.42 cm and left ventricular mass index* ≤ 95 g/m2 for females or ≤ 115 g/m2 for males; Concentric Hypertrophy: relative wall thickness > 0.42 cm and left ventricular mass index* > 95 g/m2 for females or > 115 g/m2 for males; Eccentric Hypertrophy: relative wall thickness < 0.42 cm and left ventricular mass index* > 95 g/m2 for females or > 115 g/m2 for males. *Left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area. There was 189 participants with concentric remodeling, 48 participants with concentric hypertrophy, and 22 participants with eccentric hypertrophy.

Model 1 includes adjustment for age, sex, race, CARDIA field center, mean 24-hour heart rate, and body mass index;

Model 2 includes Model 1 covariates plus additional adjustment for diabetes, education, alcohol intake, smoking status, physical activity, estimated glomerular filtration rate, albumin to creatinine ratio and antihypertensive medication use.

Abbreviations: BP = blood pressure

Associations of High Awake and Asleep Diastolic BP and Non-dipping Diastolic BP with LVMI, LVH, and Abnormal LV Geometry

Higher awake and asleep diastolic BP were associated with increased LVMI (Supplemental Figure 1). The percent dipping in diastolic BP was not associated with increased LVMI. After adjustment for age, sex, CARDIA field center, heart rate and BMI, high awake diastolic BP and high asleep diastolic BP were each associated with LVH (Supplemental Table 1). These associations were not statistically significant after additional adjustment for asleep and awake diastolic BP respectively. There was no evidence of an association between non-dipping diastolic BP and LVH in unadjusted or adjusted models. Additionally, there was no evidence of associations between the cross-classification of high awake and high asleep diastolic BP on LVH (data not shown). Higher awake and asleep diastolic BP, but not diastolic BP dipping, were associated with larger relative wall thickness (Supplemental Figure 2). In adjusted models, participants with high awake diastolic BP but not high asleep diastolic BP and those with high awake and asleep diastolic BP were more likely to have concentric remodeling (Supplemental Table 2). High awake and asleep diastolic BP was associated with a higher OR for concentric hypertrophy. None of the BP categories were associated with eccentric hypertrophy.

Effect Modification of Race and Sex

All p-values for interactions of race or sex with awake systolic and diastolic BP, asleep systolic and diastolic BP and non-dipping systolic and diastolic BP predicting LVH and LV geometry were > 0.05 in unadjusted and adjusted models.

Sensitivity Analyses using the Awake and Asleep BP Thresholds Recommended in the 2018 ESC/ESH Guideline

Using the 2018 ESC/ESH BP thresholds, 19.9% of participants with high awake systolic BP and 22.2% of participants with high asleep systolic BP had LVH. The associations of high awake and separately high asleep BP with LVH were unchanged (Supplemental Table 3). The prevalence of LVH was higher among participants with versus without high awake systolic BP in an unadjusted model and after each level of adjustment. The prevalence of LVH was higher among participants with versus without high asleep systolic BP in an unadjusted and partially adjusted models, but this association was attenuated after further adjustment for awake systolic BP (PR 1.58 [95% CI 0.86, 2.87; p=0.138]). Using categories defined by the cross-classification of high awake systolic BP and high asleep systolic BP, participants with both high awake systolic BP and high asleep systolic BP were more likely to have LVH (Supplemental Table 4). The associations of categories defined by the cross-classification of high awake and high asleep systolic BP with abnormal left ventricular geometry, and analyses of diastolic BP were similar to those observed using the 2017 ACC/AHA BP thresholds (Supplemental Tables 5–7).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based study of black and white adults in the US, higher awake systolic BP and higher asleep systolic BP were each associated with higher LVMI. After adjustment for demographics and CVD risk factors, high awake systolic BP and high asleep systolic BP were associated with a higher prevalence of LVH. The association between asleep systolic BP and LVH was attenuated and no longer statistically significant after further adjustment for awake systolic BP. Non-dipping systolic BP was not associated with a higher prevalence of LVH. Higher awake systolic BP and higher asleep systolic BP were each associated with greater relative wall thickness. High awake systolic BP was associated with concentric remodeling and hypertrophy regardless of whether asleep BP was high or not. Having both high awake systolic BP and asleep systolic BP was associated with having eccentric hypertrophy. There was no evidence of effect modification by either race or sex, suggesting that the aforementioned associations were similar for blacks and whites, and men and women in this sample. With the exception of the association of high awake systolic BP but not high asleep systolic BP with LVH, the results were similar when using the awake and asleep BP thresholds recommended in the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines.

Prior studies have consistently demonstrated associations of awake BP and asleep BP with LV mass and LVH [30–35]. In contrast, there have been conflicting findings regarding whether an association exists between non-dipping BP and LV mass and hypertrophy [15–18,35,36]. One explanation for the lack of association in some prior studies is that non-dipping is a heterogeneous phenotype that occurs among individuals with both high awake and asleep BP but also in those with low awake and asleep BP. In contrast to those with low awake BP and non-dipping BP, individuals with high awake BP and non-dipping BP may have persistently high BP (i.e., both high awake BP and asleep BP) across the 24-hour period. As BP dipping status is a measure derived from both awake BP and asleep BP, focusing on non-dipping BP in isolation ignores the individual contributions of awake BP and asleep BP to outcomes. Adverse LV geometric changes occur in response to increased pressure demands on the heart due to hypertension, and are less likely to manifest in individuals with non-dipping BP with low awake BP and low asleep BP [37]. The studies that reported an association between non-dipping and LV mass and hypertrophy examined individuals with untreated and treated hypertension who had predominantly high awake BP and high asleep BP [15,16]. In contrast, the CARDIA study participants included in this analysis comprised individuals with a wide range of awake and asleep BP levels. Thus, these data confirm the importance of high BP on ambulatory monitoring as opposed to other characteristics of the recordings.

An intensive BP reduction strategy (systolic BP <120 mm Hg vs. <140 mm Hg) was associated with lower awake and asleep systolic BP on ambulatory BP monitoring [38], but it remains to be determined how much reducing awake BP, asleep BP or both contribute to the regression of LVH or reduction of CVD events. Future studies are needed to ascertain whether individuals with high awake BP and/or high asleep BP could benefit from initiation or intensification of BP lowering interventions targeting the awake and/or asleep periods to reverse LVH and abnormal cardiac geometry and ultimately reduce CVD event rates [39].

The current study has several strengths. Prior studies that examined the associations of high awake BP, high asleep BP, and non-dipping BP with abnormalities of cardiac structure generally enrolled white participants, whereas the CARDIA study included both black and white participants. The racial diversity of the CARDIA study population likely increases the generalizability of the current results. Further, unlike prior studies which typically enrolled participants with untreated clinic hypertension, the current study included those taking and not taking antihypertensive medication. The CARDIA study population is well-characterized and allowed us to adjust for many potential confounders. All echocardiograms were performed according to a standardized protocol and identically configured machines and centrally interpreted by expert readers. Clinic and ambulatory BP were rigorously measured in accordance with standardized protocols. Having used a wrist actigraphy device in our study to identify asleep and awake times, we were able to derive asleep and awake BP. In contrast, prior studies either relied on self-reported sleep times or used fixed clock times to define the asleep and awake periods, which is an approach that may inadvertently include awake BP readings during the asleep period, and/or asleep BP readings during the awake period [40].

There are several potential limitations that should also be taken into consideration when interpreting the current findings. Several prior studies have found associations between non-dipping BP and increased risk of death [41–44]. As little follow-up has occurred following the conduct of ABPM in the CARDIA study, we were unable to examine the associations between non-dipping BP, asleep BP, and awake BP with changes in cardiac geometry over time or the occurrence of CVD events and mortality. Due to limited funding, ABPM data were collected at only two of the four CARDIA study field centers. Further, several sub-groups of participants, including those with abnormal geometry, were small and these analyses may be underpowered. Lastly, non-dipping BP has poor reproducibility and the lack of repeated assessments of ABPM in this sample likely resulted in some misclassification of dipping status.

In summary, among black and white participants in a US community-based sample, high asleep systolic BP and high awake systolic BP were each associated with a higher prevalence of LVH after adjustment for demographics and clinical characteristics. In contrast, non-dipping systolic BP was not associated with a higher prevalence of LVH. These findings suggest that evaluating mean awake and asleep BP, rather than BP dipping, may help identify patients with high risk for cardiovascular end-organ damage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the CARDIA participants for their time and invaluable contributions to our understanding of cardiovascular health and disease.

Funding Sources:

The current study was supported by the American Heart Association grant SFRN 15SFRN2390002 and the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) which is supported by contracts HHSN268201800003I, HHSN268201800004I, HHSN268201800005I, HHSN268201800006I, and HHSN268201800007I from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). NAB received support from the NIH/NHLBI (K23 HL136853). DS received support through K24-HL125704 from NIH/NHLBI. MA received support from UL1TR001873 and KL2TR001874 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH. JNBIII received research support through the American Heart Association grant SFRN 15SFRN2390002.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have nothing to declare.

No portion of this work has been previously presented or published

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018; 71: e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, Ho KK. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 1996; 275:1557–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation 2000; 102:470–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vakili BA, Okin PM, Devereux RB. Prognostic implications of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J 2001; 141: 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gidding SS, Liu K, Colangelo LA, Cook NL, Goff DC, Glasser SP, et al. Longitudinal determinants of left ventricular mass and geometry: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 6:769–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu K, Colangelo LA, Daviglus ML, Goff DC, Pletcher M, Schreiner PJ, et al. Can Antihypertensive Treatment Restore the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease to Ideal Levels?: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4:e002275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. New Engl J Med 2006; 354 (22):2368–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Metoki H, Obara T, Saito S, et al. Ambulatory Blood Pressure and 10-Year Risk of Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Mortality. The Ohasama Study. Hypertension 2005; 45:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, et al. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: a cohort study. Lancet 2007; 370 (9594):1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen TW, Jeppesen J, Rasmussen S, Ibsen H, Torp-Pedersen C. Ambulatory Blood Pressure and Mortality. A Population-Based Study. Hypertension 2005; 45:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Otero A, Dominguez-Sardina M, Moya A, Rios MT, et al. Asleep blood pressure: significant prognostic marker of vascular risk and therapeutic target for prevention. Eur Heart J 2018; 39:4159–4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber MA, Drayer JIM, Nakamura DK, Wyle FA. The circadian blood pressure pattern in ambulatory normal subjects. Am J Cardiol 1984; 54:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkenhager AM, van den Meiracker AH. Causes and consequences of a non-dipping blood pressure profile. Neth J Med 2007; 65:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuspidi C, Giudici V, Negri F, Sala C. Nocturnal nondipping and left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: an updated review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010; 8:781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Routledge FS, McFetridge-Durdle JA, Dean CR. Night-time blood pressure patterns and target organ damage: a review. Can J Cardiol 2007; 23:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallion JM, Baguet JP, Siche JP, Tremel F, De Gaudemaris R. Clinical value of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens 1999; 17:585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancia G, Parati G. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and organ damage. Hypertension 2000; 36:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41:1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas SJ, Booth JN 3rd, Dai C, Li X, Allen N, Calhoun D, et al. Cumulative Incidence of Hypertension by 55 Years of Age in Blacks and Whites: The CARDIA Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7: pii: e007988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs DR Jr., Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and Reliability of Short Physical Activity History: Cardia and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1989; 9:448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Assaad MA, Topouchian JA, Darne BM, Asmar RG. Validation of the Omron HEM-907 device for blood pressure measurement. Blood Press Monit 2002; 7:237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, Li Y, Dolan E, et al. The International Database of Ambulatory Blood Pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDACO): protocol and research perspectives. Blood Press Monit 2007; 12:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien E, Sheridan J, O’Malley K. Dippers and non-dippers. Lancet 1988; 2 (8607):397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 Practice Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: ESC/ESH Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018; 36:2284–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong AC, Ricketts EP, Cox C, Adler P, Arynchyn A, Liu K, et al. Quality Control and Reproducibility in M-Mode, Two-Dimensional, and Speckle Tracking Echocardiography Acquisition and Analysis: The CARDIA Study, Year 25 Examination Experience. Echocardiography 2015; 32:1233–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015; 28:1–39 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou G A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuspidi C, Sala C, Valerio C, Negri F, Mancia G. Nocturnal hypertension and organ damage in dippers and nondippers. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25:869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatasciore A, Renda G, Zimarino M, Soccio M, Bilo G, Parati G, et al. Awake systolic blood pressure variability correlates with target-organ damage in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension 2007; 50:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cicconetti P, Morelli S, Ottaviani L, Chiarotti F, De Serra C, De Marzio P, et al. Blunted nocturnal fall in blood pressure and left ventricular mass in elderly individuals with recently diagnosed isolated systolic hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2003; 16:900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Androulakis E, Papageorgiou N, Chatzistamatiou E, Kallikazaros I, Stefanadis C, Tousoulis D. Improving the detection of preclinical organ damage in newly diagnosed hypertension: nocturnal hypertension versus non-dipping pattern. J Hum Hypertens 2015; 29:689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagard R, Staessen JA, Thijs L. The relationships between left ventricular mass and daytime and night-time blood pressures: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Hypertens 1995; 13:823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Guerrieri M, Gatteschi C, Benemio G, Boldrini F, et al. Circadian blood pressure changes and left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. Circulation 1990; 81:528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuspidi C, Lonati L, Sampieri L, Michev I, Macca G, Rocanova JI, et al. Prevalence of target organ damage in treated hypertensive patients: different impact of clinic and ambulatory blood pressure control. J Hypertens 2000; 18:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaasch WH, Zile MR. Left ventricular structural remodeling in health and disease: with special emphasis on volume, mass, and geometry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:1733–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drawz PE, Pajewski NM, Bates JT, Bello NA, Cushman WC, Dwyer JP, et al. Effect of Intensive Versus Standard Clinic-Based Hypertension Management on Ambulatory Blood Pressure: Results From the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) Ambulatory Blood Pressure Study. Hypertension 2017; 69:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuspidi C, Michev I, Meani S, Valerio C, Bertazzoli G, Magrini F, et al. Non-dipper treated hypertensive patients do not have increased cardiac structural alterations. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2003; 1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth JN 3rd, Muntner P, Abdalla M, Diaz KM, Viera AJ, Reynolds K, et al. Differences in night-time and daytime ambulatory blood pressure when diurnal periods are defined by self-report, fixed-times, and actigraphy: Improving the Detection of Hypertension study.J Hypertens 2016; 34:235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Yamaguchi J, Kikuya M, Ohmori K, Michimata M, et al. Prognostic significance of the nocturnal decline in blood pressure in individuals with and without high 24-h blood pressure: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens 2002; 20:2183–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation 2005; 111:1777–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, Hinedi K, Atkins N, McClory S, et al. Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertension 2005; 46:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben-Dov IZ, Kark JD, Ben-Ishay D, Mekler J, Ben-Arie L, Bursztyn M. Predictors of all-cause mortality in clinical ambulatory monitoring: unique aspects of blood pressure during sleep. Hypertension 2007; 49:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.