Abstract

The accurate prediction of a cancer patient’s risk of progression or death can guide clinicians in the selection of treatment and help patients in planning personal affairs. Predictive models based on patient-level data represent a tool for determining risk. Ideally, predictive models will use multiple sources of data (e.g., clinical, demographic, molecular, etc.). However, there are many challenges associated with data integration, such as overfitting and redundant features. In this paper we aim to address those challenges through the development of a novel feature selection and feature reduction framework that can handle correlated data. Our method begins by computing a survival distance score for gene expression, which in combination with a score for clinical independence, results in the selection of highly predictive genes that are non-redundant with clinical features. The survival distance score is a measure of variation of gene expression over time, weighted by the variance of the gene expression over all patients. Selected genes, in combination with clinical data, are used to build a predictive model for survival. We benchmark our approach against commonly used methods, namely lasso-as well as ridge-penalized Cox proportional hazards models, using three publicly available cancer data sets: kidney cancer (521 samples), lung cancer (454 samples) and bladder cancer (335 samples). Across all data sets, our approach built on the training set outperformed the clinical data alone in the test set in terms of predictive power with a c.Index of 0.773 vs 0.755 for kidney cancer, 0.695 vs 0.664 for lung cancer and 0.648 vs 0.636 for bladder cancer. Further, we were able to show increased predictive performance of our method compared to lasso-penalized models fit to both gene expression and clinical data, which had a c.Index of 0.767, 0.677, and 0.645, as well as increased or comparable predictive power compared to ridge models, which had a c.Index of 0.773, 0.668 and 0.650 for the kidney, lung, and bladder cancer data sets, respectively. Therefore, our score for clinical independence improves prognostic performance as compared to modeling approaches that do not consider combining non-redundant data. Future work will concentrate on optimizing the survival distance score in order to achieve improved results for all types of cancer.

Keywords: data integration, feature selection, feature reduction, survival analysis, cancer

1. Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States with approximately 600,000 deaths in 2016 [1]. Accurate prediction of survival has immense importance to cancer patients for treatment and life-planning. This includes the regulation of personal affairs and the decision whether additional aggressive or experimental treatment options should be used. Therefore, for a patient with poor prognosis beyond a few weeks, the question arises whether that patient should initiate an exhausting chemotherapy or should concentrate on the remaining quality of life [2, 3]. For health care professionals, a good predictive model of the risk of an event is important for the decision-making process of treatments. For any individual with a life-threatening condition, the benefit that a treatment presents might be outweighed by its risks the shorter their expected survival time is.

In many cases, predictive models are generated based on clinical data, such as patient age or tumor status [4–7]. Other possibilities include the use of biological markers, such as gene expression, because cancer is due to mutated behavior of the cells [8]. A potential way to improve the performance of predictive models involves using both clinical data and biological markers, because when they provide non-redundant information, a more accurate picture about the course of cancer might be built. However, integrating data in this way increases the number of features, which leads to an increased computational burden, an increased risk of overfitting, and an increased risk of correlation between the features [9]. Highly correlated features create redundant information which could lead to imprecise regression coefficients and very large standard errors. To get around this problem, intensive research has been conducted in recent decades to reduce the number of features without losing information needed to predict risk. In addition, feature selection can help clinicians to better understand key factors and their relationships, by providing a more interpretable model.

Feature selection methods can be categorized into supervised, semi-supervised and unsupervised algorithms [10]. Among the supervised methods are filter methods, wrapper methods, and embedded methods. Filter methods consider the relationship of feature and target variable to understand the importance of the feature. The feature selection takes place before the actual modelling. Wrapper methods generate models with subsets of features and determine model performance. They often provide good results, but these methods are computationally very expensive. Embedded methods were designed to bridge the gap between the accuracy of the wrapper methods and the computational efficiency of the filter methods. A well-known method is lasso [11], which is a further development of ridge regression [12]. Lasso introduces a constraint to estimating a model such that the sum of the absolute values of the regression coefficients must be less than a specified threshold. This causes many of the coefficients to be set to zero, thus selecting only a subset of the features for the model [13]. The general idea is applicable to many models. In this case it is applied to Cox regression [14], which is often used to predict the hazard of an event in survival analysis. In contrast to lasso, ridge regression reduces the values of the regression coefficients and thus reduces overfitting but does not perform any feature selection.

Highly predictive genomic features most likely provide similar information about the outcome of the disease as the clinical variables because most clinical variables have an association with genomic predictors. To improve the predictive power, we want to select features which are still predictive of the outcome but are not redundant with the clinical variables. To achieve this, one method is to select features before the actual model building process (in contrast to lasso) by choosing a filter feature selection method, specifically, a method which selects features that are the most consistent discriminators in their expression over time. So far, the applicability of filter feature selection methods to survival data is questionable due to censoring. Particularly, methods for feature selection in case-only analysis of time-to-event endpoint studies present a challenge.

Here, we introduce a survival distance scoring algorithm, a novel filter feature selection method which scores genes according to their association with survival. In order to improve the predictive power of features selected by this score, we reduce correlated features with a novel feature reduction method and we combine those new created features with the clinical data of the subjects. In the following, the algorithm is explained. In addition, its performance is compared to lasso and ridge-penalized Cox proportional hazards models, and models built from the clinical data alone, using gene expression data and clinical data from bladder cancer, lung cancer and kidney cancer.

2. Methods

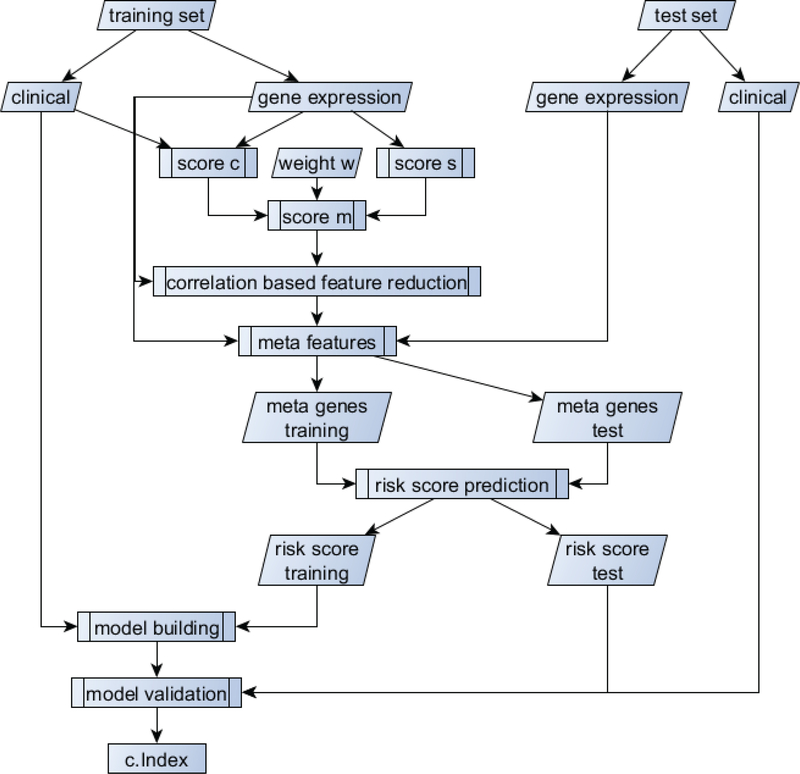

The workflow for the proposed method can be found in Figure 1. Briefly, we first separate the dataset into training and testing sets. Using the training data only, we use a combination of the survival distance score (score s) and the score for clinical independence (score c) to select the best performing genes. Using those genes, we then perform correlation-based feature reduction to meta genes, which are then used as features in a risk prediction model. The risk prediction will be considered as a risk score and in combination with the clinical data will be used in the final model building process. The single steps will be explained in detail in the following sub-sections.

Figure 1:

Workflow for the model building process and gain of the performance metric (c.Index).

2.1. Survival Distance Score

We devised two metrics for selecting genes associated with survival, described below. Consider a sample of subjects ranging from 1 to N. The censoring indicator δ (0 – censored, 1 - event) classifies each subject at time t, where t is the timepoint of an event (e.g. death) or the last follow-up time for a subject (censoring) (see Table 1). The group of subjects i with an event/censoring at timepoint t is denoted as At, whose size, nt, can theoretically range from 1 to N. Let ygi represent the value of the gth attribute, g = 1,2, …,G in subject i = 1,2, …,N, where ygi is assumed to have variance .

Table 1 :

Description of notation used for the method.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| i | Subject, where i = 1,2, …,N |

| g | Attribute |

| δ | Censoring indicator (0-censored, 1-event) |

| t | Timepoint of event or last follow-up time |

| At | Group of subjects with event/censoring at timepoint t |

| ygi | Value of gth attribute in subject i, |

| Variance of ygi | |

| Average of attribute g of subjects who survived beyond time t | |

| Average of attribute g of subjects who experienced event before time t | |

| Group size of subjects who survived beyond time t | |

| Group size of subjects who experienced event before time t | |

| nt | Group size of subjects who experienced event at time point t |

2.1.1. Score for survival distance s

Inspired by the Fisher score [15], we devised a score (denoted s) for each attribute (e.g., genes, in our case), which increases when variation of that attribute is associated with variation in some endpoint of interest (e.g., survival). To achieve this, we compare the value of an attribute observed for a subject with event time, t, with the average of that attribute calculated amongst subjects who survived beyond time t () and those who experienced the event before time t (). Additionally, we compensate for the group size used to achieve the particular averages of the groups . In the case that more than one subject had an event at a specific timepoint, we add the average of the obtained scores at this timepoint to the overall score of the attribute. Finally, each score for an attribute will be weighted by the attribute variance over all timepoints. The score s is in [0, ∞). Increasing values of s represent a stronger dependency between the attribute and the timepoint of an event. Thus, the score will be large when attributes are dispersed with respect to subjects at all time points, rather than just a few of them, therefore, the score will be large for attributes that are the most consistent discriminators of expression values over time. The calculation of this score can be expressed in Eq. (1). Furthermore, we give the pseudo code for the calculation of the score below.

| (1) |

Pseudo code for the calculation of score 5:

set all scores sg = 0

for t in 1 to max time

for all subjects x with overall survival time > t

= mean value for each attribute

= number of subjects

for all subjects x with overall survival time < t and who are not censored

= mean value for each attribute

= number of subjects

bgt = 0

for all subjects x with event at time t

2.1.2. Score for clinical independence c

In addition, a score cg is created by fitting a linear regression to each attribute independently, including the clinical data as predictors and modeling attribute values as outcome. For each model, we calculate 1 minus the coefficient of determination (R2). Therefore, when cg is close to one, the value of the attribute was not explained by the clinical data (e.g., gene g is independent of the clinical data).

| (2) |

2.1.3. Combination of the scores

Since score distributions differed in location and scale, both scores, sg and cg, were standardized. For optimized results in feature selection one of the scores is weighted while the other is held constant. In this case cg was weighted, where we tested weights w from 0 to 5 in increments of 0.1. For each weight, we performed the whole model building process and determined the optimal weight through cross validation using the c.Index (see Section 2.2 Model building). Adding those modified scores up leads to the final cumulative score mg for each attribute:

| (3) |

2.1.4. Feature reduction

Feature reduction was performed to increase the stability of the algorithms. For this purpose, we decided to combine correlated attributes. Since pairwise correlation is computationally complex, we did this computation only on the j highest scoring attributes where j can be determined by cross validation (in our case the 75 highest scoring genes) using the cumulative score mg. The goal was to combine those attributes, which are correlated to each other, while preserving their unique information. To do this we weighted the attributes according to their cumulative score. Particularly, taking the highest-ranking attribute we grouped it with all attributes to which it had a pairwise correlation greater than 0.6 and removed this group from the initial matrix. The attribute value ygi of each attribute g of subject i in this subgroup k was weighted according to their cumulative score mg and added up to a new feature Tki, which can be considered as a meta gene, as is shown in Eq. (4). In the next step we took the highest-ranking attribute from the remaining attributes from the initial matrix and repeated the proposed process. This procedure will be repeated until no attributes are left in the initial matrix.

| (4) |

2.2. Model building

The new features derived in the feature reduction step are used to form a Cox regression model using Ridge penalization (R package glmnet [16, 17] using function cv.glment with 5 fold cross validation). The exponential function of the linear predictor from the model, derived by the value of the penalty coefficient lambda which gives minimum mean cross-validated error (lambda.min), is taken as a genomic risk score. The risk score of the training set is used together with the clinical data to form a Cox model (R package survival [18]). This model building process is called “unpenalized model building” [19].

Using this model on the test data set, including the previously obtained risk score for the test data and the clinical data, we determined the linear predictor and calculated the concordance index (c.Index) (R package survcomp [20, 21], function concordance.index using the method ‘noether’ [22]). The c.Index determines the probability that a randomly selected subject who has experienced an event has a higher risk score than a subject who has not experienced an event before the first subject. The c.Index is thus comparable to the area under the curve of the ROC curve, where the range is from 0.5 to 1.

In the following we will call the model with the best performance at weight w for the score cg sdsc + clin. For further comparisons we will name a model sds + clin, when it was built without using the score cg. A model built without clinical data at all will be called sds.

2.3. Model validation

For the model formation a training set of two thirds of the cases was used. The remaining cases were assigned to the test set. In order to obtain reproducible results, the training and test sets were created with 100 different seeds from seed 1 to seed 100. The average of the result over all seeds was considered as the final result. This is necessary because the predictive power of a model depends very much on the distribution of subjects within the training sets and test sets.

2.4. Comparison methods

The performance of lasso and ridge with all gene expression data was determined by building the model with the R package glmnet (function cv.glmnet with 5 fold cross validation), receiving the linear predictor on the test set using lambda.min and calculating the c.Index using the R package survcomp with the function concordance.index using the method ‘noether’. Those models will now be referred to as Lasso and Ridge. The same procedure was used to obtain the c.Index for the clinical data alone (clin). However, because this model is not penalized, the tool coxph from the R package survival was used to fit it. In addition, a combination of gene expression data and clinical data was tested with lasso and ridge by simply including all features in the penalized model (“Lasso + clin” and “Ridge + clin”) and in the same way as our method using the unpenalized model building process. Those models will be called “Lasso + clin unp” and “Ridge + clin unp”, respectively.

2.5. Data

All data used in this work are from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). They are available from https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ [23].

Three sets of raw count gene expression (level 3) data from the TCGA database were used to analyze and create the model (see Table 2). We used bladder cancer with transitional cell carcinoma (335 cases, submitter id: TCGA-BLCA [24, 25]), kidney cancer (521 cases, submitter id: TCGA-KIRC [26]) and lung cancer (521 cases, submitter id: TCGA-LUAD [27]). We only used samples of primary tumors with unique case ID. In addition, all cases considered have a survival time greater than 0 days after diagnosis.

Table 2:

Composition of data sets.

| Bladder cancer | Lung cancer | Kidney cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # cases | 335 | 454 | 521 |

| median age | 69.3 | 66.4 | 61.1 |

| # female | 91 | 250 | 182 |

| # male | 244 | 204 | 339 |

| # stage I | 1 | 250 | 261 |

| # stage II | 96 | 106 | 65 |

| # stage III | 119 | 74 | 122 |

| # stage IV | 120 | 24 | 82 |

| # events | 155 | 172 | 172 |

2.5.1. Data preparation

The raw count gene expression data were normalized using R tools edgeR and Limma [18, 19, 26]. Subsequently we wanted to remove genes with low variance and therefore not enough information for our purpose. We used median absolute deviation instead of the standard deviation as it is more robust and resilient to outliers. All genes that have a smaller MAD than 1.4 for bladder cancer were filtered out so that approximately 12,000 genes remained. For comparability, the cut off values for MAD were set to 1.3 for kidney cancer and 1.34 for lung cancer so that as well approximately 12,000 genes remained.

Clinical data included tumor status, sex, and age, where the age at time of diagnosis had to be imputed using predictive mean matching (pmm) for one case of kidney cancer and 19 cases of lung cancer. For this the R package mice was used [28].

3. Results

3.1. Bladder cancer

The performance of score s improves significantly (p < 2.2e-16) when combined with clinical data.

Here one can observe a rise in the c.Index from 0.599 for sds to 0.646 for sds + clin (see Table 3 and Figure 2). The use of genes independent of the clinical data in combination with clinical data (sdsc + clin ) leads to a further, albeit slight, improvement of the predictive power with a c.Index of 0.648 (w = 2.3). This may be because genes have been selected by our method which provide independent information from the clinical data, but the results suggest that genomic risk score derived from score s is already mostly independent of the clinical variables.

Table 3:

Results of prediction of survival risk with different models on bladder cancer, kidney cancer and lung cancer. The values in the cells are the c.Index. The best performing method for each cancer is shown in bold.

| Bladder cancer | Lung cancer | Kidney cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| sdsc + clin | 0.6484 | 0.6946 | 0.7733 |

| sds + clin | 0.6457 | 0.6929 | 0.7693 |

| sds | 0.5990 | 0.6310 | 0.6949 |

| Ridge + clin unp | 0.6502 | 0.6676 | 0.7727 |

| Ridge + clin | 0.6357 | 0.6256 | 0.7125 |

| Ridge | 0.6354 | 0.6252 | 0.7115 |

| Lasso + clin unp | 0.6450 | 0.6774 | 0.7670 |

| Lasso + clin | 0.6073 | 0.6319 | 0.7445 |

| Lasso | 0.6075 | 0.6315 | 0.6908 |

| clin | 0.6357 | 0.6641 | 0.7548 |

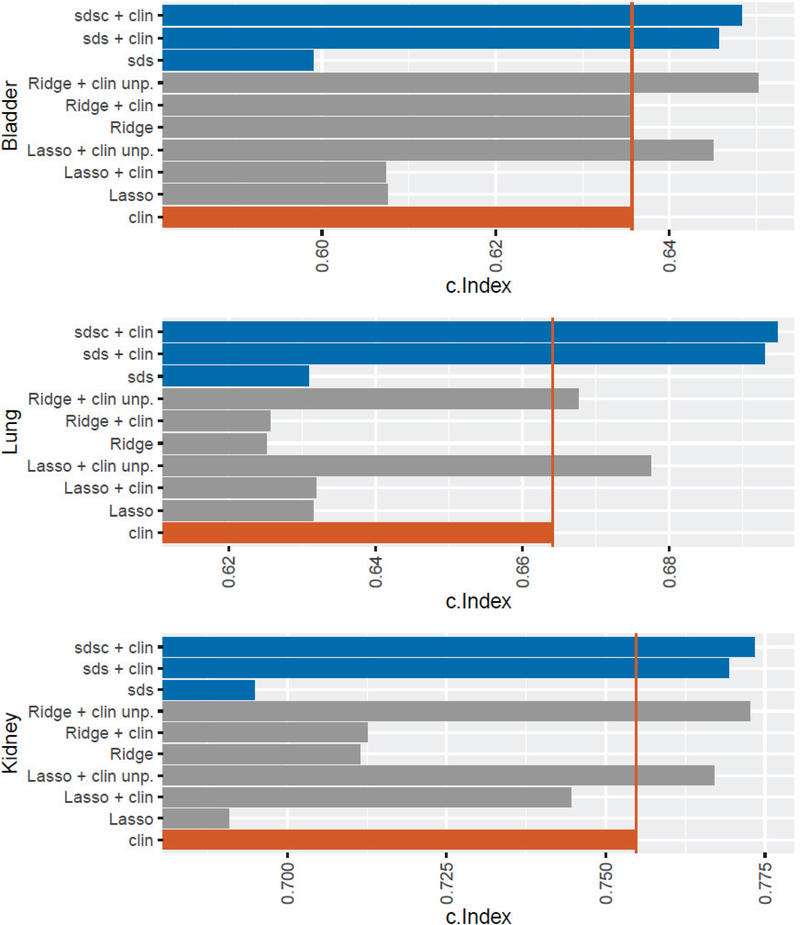

Figure 2:

For each type of cancer, a comparison was performed by Lasso and Ridge with gene expression data and clinical data alone. In addition, the combination of gene expression data and clinical data was tested with Lasso and Ridge using a penalized and an unpenalized model building process. For the diagnosis, the base value of sds was tested without the combination with clinical data. Finally, here the performance of sds in combination with clinical data is shown once without the use of cg and with the use of cg at the best weight. The red vertical line marks the c.Index of the clinical data alone.

Lasso’s performance is worse than Ridge’s with c.Index’s of 0.608 and 0.635, respectively, suggesting that feature selection has lost important information. The clinical data have a c.Index of 0.636. The combination of clinical data with gene expression data has no effect but using the unpenalized model building process leads to an improvement in the performance of both Lasso + clin unp (c.Index = 0.645) and Ridge + clin unp (c.Index = 0.650), with both models performing better than the clinical data alone. It is noteworthy that sdsc + clin performs better than Lasso + clin unp, although not significantly (p = 0.456). However, the performance of Ridge + clin unp is marginally better to that of sdsc + clin. Since Ridge + clin unp does not do feature selection, sdsc + clin is to be preferred, in part because clinically a panel of only 75 genes compared to 12,000 is more interpretable, more affordable, and likely more reliable. For both sds + clin and sdsc + clin, however, there is a strong improvement to Lasso + clin.

3.1. Lung cancer

As with bladder cancer, the performance of score s improves significantly (p < 2.2e-16) when clinical data is additionally used with an increase from 0.631 for sds to 0.693 for sds + clin. Also further improvement can be noted if gees independent of clinical data were used (model sdsc + clin). Also, there is again a slight improvement in predictive power from sds + clin to sdsc + clin with a rise from 0.693 (w = 1.3).

Unlike bladder cancer, Lasso’s predictive power is better than Ridge’s, suggesting that Ridge overfitted. The combination of clinical data with genomic data using the unpenalized model building process leads to an improvement in performance with c.Index’s of 0.677 for Lasso + clin unp and 0.668 for Ridge + clin unp. The clinical data alone have a better performance tan Lasso or Ridge, but a worse one than Lasso + clin unp or Ridge + clin unp. However, the best performance has sdsc + clin, which outperforms Lasso + clin unp significantly (p = 6.003e-05). Here, as with bladder cancer, one can observe that data integration leads to an improvement in the predictive power of clinical data.

3.2. Kidney cancer

As with bladder cancer and lung cancer, predictive power increases significantly (p < 2.2e-16) when score s is linked to clinical data with an increase from 0.695 for sds to 0.769 for sds + clin. Also, further improvement was noted when genes independent of clinical data were used in model sdsc + clin (c.Index = 0.773), although again very slight.

As with bladder cancer, the predictive power of Lasso (c.Index = 0.691) is weaker than that of Ridge (c.Index = 0.712). Both Lasso and Ridge have a weaker performance than the clinical data (c.Index = 0.755). However, when genomic data are linked to clinical data using the unpenalized model building process, the performance is better than clinical data alone with a c.Index of 0.767 for Lasso + clin unp and 0.773 for Ridge + clin unp. Here, too, it can be observed that sdsc + clin provides a better predictive power than Lasso + clin unp, although not significant (p = 0.08369).

4. Conclusion and Discussion

In this work, we have proposed a method for selecting features that work well together across divergent datasets to build improved risk models for cancer. We have shown that the combination of gene expression data and clinical data is superior to the predictive power of gene expression data or clinical data alone, for these datasets. This applies to standard feature selection methods such as lasso-penalized models as well as a survival distance score (sds) inspired by Fisher’s score. To achieve this result, we proposed combining a single genomic risk score with clinical data into a final model (this was done for all comparison methods). It is worth noting that this is a modified way of model building using ridge regression, as we have described, with better performance than a naïve approach would have. However, the advantage from further constraining the features to be independent, although always advantageous, was very slight. This suggests that the genomic risk score generated using sds was already fairly independent of the clinical variables, although in principle the approach appears to have worked. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the feature selection and reduction methods we introduced in this work are effective, irrespective of the independence part of the methodology.

Although these gains are relatively modest, we have shown that it is possible to improve the power of predicting the risk of an event in different cancers by combining clinical data and genomic data using a method that tries to find the best combination of data across datasets. Thus, it seems likely that further development of these ideas will yield even greater gains. However, we note that our idea may have general applicability to other types of data integration (e.g. DNA methylation).

It is important to mention that we are not proposing clinical models for the different cancer types. Rather, we are demonstrating that the proposed novel filter feature selection method, which combines clinical data with non-redundant molecular data, achieves an improved prognostic performance in a case-only analysis of a time-to-event endpoint compared to modeling approaches that do not consider combining non-redundant data. To compare the three cancer types, we reduced the clinical data to the most common predictive clinical variables.

Although ridge-penalized Cox proportional hazards models resulted in adequate prognostic performance and are comparatively easy to employ, ridge penalization does not enable feature selection, and is therefore harder to interpret given the high-dimensionality of genomic data. Furthermore, it is more cost efficient to analyze only a few dozen features instead of thousands. On the other hand, while lasso-penalized Cox proportional hazards models perform feature selection, they can perform poorly when applied to correlated data [29]. As genomic features are often highly correlated, application of lasso-penalized models to such data could hinder prognostic performance, which is consistent with what we observed in this study. Our method on the other hand, incorporates both feature selection and feature reduction. Additionally, the survival distance score can accommodate a large fraction of censored observations. One limitation of the survival distance score however, is the use of a tuning parameter in the form of the number of top scoring genes, which are selected before the feature reduction step. We derived this tuning parameter empirically but note that this number may not be globally applicable across studies. Additionally, future work will examine if the performance of sdsc+clin could be further enhanced and how it performs compared to other filter feature selection methods.

5. Acknowledgements

Acknowledged is the contribution of the Statistical ‘omics Working Group of the Department of Biostatistics and Data Science at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

* This work is supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA168524.

References

- 1.Statistics, C.N.C. f.H. Leading Causes of Death. 2017. March 17, 2017 [cited 2019; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm.

- 2.Temel JS, et al. , Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(17): p. 2319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weeks JC, et al. , Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 1998. 279(21): p. 1709–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vickers AJ, et al. , Clinical benefits of a multivariable prediction model for bladder cancer: A decision analytic approach. Journal of Urology, 2008. 179(4): p. 320–320. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapur N, et al. , Predicting the Risk of High-Grade Bladder Cancer Using Noninvasive Data. Urologia Internationalis, 2011. 87(3): p. 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman DM, et al. , Nomogram to Predict Cycle-One Serious Drug-Related Toxicity in Phase I Oncology Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2014. 32(6): p. 519-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pond GR, et al. , Nomograms to predict serious adverse events in phase II clinical trials of molecularly targeted agents. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2008. 26(8): p. 1324–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AJF G, et al. , An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. New York: W. H. Freeman, 2000. 7th edition. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asaithambi S Why, How and When to apply Feature Selection. 2018. [cited 2019; Available from: https://towardsdatascience.com/why-how-and-when-to-apply-feature-selection-e9c69adfabf2.

- 10.Tang J, Alelyani S, and Liu H, Feature Selection for Classification: A Review, in Data Classification: Algorithms and Applications. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibshirani R, The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Stat Med, 1997. 16(4): p. 385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoerl AE, Application of Ridge Analysis to Regression Problems. Chemical Engineering Progress, 1962. 58(3): p. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonti V and Belitser DE, Feature Selection using LASSO. VU Amsterdam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox DR, Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology, 1972. 34(2): p. 187-+. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longford NT, A Fast Scoring Algorithm for Maximum-Likelihood-Estimation in Unbalanced Mixed Models with Nested Random Effects. Biometrika, 1987. 74(4): p. 817–827. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon N, et al. , Regularization Paths for Cox’s Proportional Hazards Model via Coordinate Descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 2011. 39(5): p. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman J, Hastie T, and Tibshirani R, Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 2010. 33(1): p. 1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JCA, Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. Sociological Methods & Research, 2003. 32(1): p. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson JA, Christensen BC, and Marsit CJ, Methylation-to-Expression Feature Models of Breast Cancer Accurately Predict Overall Survival, Distant-Recurrence Free Survival, and Pathologic Complete Response in Multiple Cohorts. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder MS, et al. , survcomp: an R/Bioconductor package for performance assessment and comparison of survival models. Bioinformatics, 2011. 27(22): p. 3206–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haibe-Kains B, et al. , A comparative study of survival models for breast cancer prognostication based on microarray data: does a single gene beat them all? Bioinformatics, 2008. 24(19): p. 2200–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pencina MJ and D’Agostino RB, Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Statistics in Medicine, 2004. 23(13): p. 2109–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman RL, et al. , Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(12): p. 1109–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson AG, et al. , Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell, 2018. 174(4): p. 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature, 2014. 507(7492): p. 315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature, 2013. 499(7456): p. 43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature, 2014. 511(7511): p. 543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Buuren S and Groothuis-Oudshoorn K, mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 2011. 45(3): p. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou H and Hastie T, Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net (vol B 67, pg 301, 2005). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology, 2005. 67: p. 768–768. [Google Scholar]