Summary

Li4Ti5O12 anode can operate at extraordinarily high rates and for a very long time, but it suffers from a relatively low capacity. This has motivated much research on Nb2O5 as an alternative. In this work, we present a scalable chemical processing strategy that maintains the size and morphology of nano-crystal precursor but systematically reconstitutes the unit cell composition, to build defect-rich porous orthorhombic Nb2O5-x with a high-rate capacity many times those of commercial anodes. The procedure includes etching, proton ion exchange, calcination, and reduction, and the resulting Nb2O5-x has a capacity of 253 mA h g−1 at 0.5C, 187 mA h g−1 at 25C, and 130 mA h g−1 at 100C, with 93.3% of the 25C capacity remaining after cycling for 4,000 times. These values are much higher than those reported for Nb2O5 and Li4Ti5O12, thanks to more available surface/sub-surface reaction sites and significantly improved fast ion and electron conductivity.

Subject Areas: Energy Storage, Chemical Synthesis, Energy Materials

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

A novel micro-etching strategy is developed to prepare porous nano-crystal Nb2O5

-

•

The obtained Nb2O5 remains the morphology of the precursor but reconstructs unit cell

-

•

Oxygen vacancies and Nb4+/Nb5+ are introduced to porous Nb2O5-x by anoxic annealing

-

•

Defect-rich and porous Nb2O5-x works as durable, high-rate, and safe anode of LIBs

Energy Storage; Chemical Synthesis; Energy Materials

Introduction

Commercial lithium-ion Li4Ti5O12 anodes currently in use in power lithium ion batteries (LIBs) on buses have an advantage over other commercial anodes because their capacity can sustain high rates. For example, graphite has a capacity of 62 mA h g−1 at 10 C compared with 311 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C and silicon-carbon composite (Si/C) has 54 mA h g−1 at 10 C and 440 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C, but Li4Ti5O12's capacity of 145 mA h g−1 at 10 C is rather close to that of 170 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C (Wang et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the capacity of Li4Ti5O12 is relatively low, so there is much impetus to find a higher-capacity replacement that can retain the advantage of rate insensitivity.

As Li4Ti5O12, other early transition metal oxides comprised of similar mostly corner-sharing octahedra can also reversibly incorporate Li while retaining the structure without inordinate volume changes, thus providing better rate and cyclic performance. Among them, recent interest has been directed to NbxWyOz (Griffith et al., 2018) featuring outstanding anode properties, but being one of the simplest such oxides, Nb2O5 has already received much attention. Dunn et al. reported a mesoporous orthorhombic Nb2O5 nanocrystal, which, when combined with an equal mass of conducting carbon black, can make electrodes of 145 mA h g−1 at 1 C and 105 mA h g−1 at 100 C (Augustyn et al., 2013); however, at a more common ratio of active material (Nb2O5) to carbon black of ∼8:1, its high-rate capacity is still limited. Other studies of orthorhombic Nb2O5 (also denoted as T- Nb2O5 in the literature) in the form of hollow nanosphere (Kong et al., 2014), nanobelt (Wei et al., 2008), nanosheet (Kong et al., 2015), and nanofiber (Viet et al., 2010) all reported broadly similar properties, with values such as 250 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C in the first cycle that drops to 180 mA h g−1 in the 50th cycle. Instead of using carbon black, various constructs to introduce current collectors, such as carbonaceous coating or inclusions, co-assemblies of Nb2O5 nanorods and carbon fiber (Deng et al., 2018a), and composites with holey graphene, have been explored, which achieved first-cycle values such as 190 mA h g−1 at 200 mA g−1 (1 C) and 90 mA h g−1 at 20,000 mA g−1 (100 C) (Sun et al., 2017). These devices already have properties approaching the theoretical capacity (200 mA h g−1) of Nb2O5, but they also require complicated designs or synthesis, which is a potentially serious impediment toward practical applications.

Because orthorhombic Nb2O5 does have a higher theoretical capacity, we have sought to find a simple fabrication strategy to directly impart fast Li and electron conductivities into additive-free Nb2O5 to achieve high performance. Such a strategy is reported in this study, in which we fabricated well-crystallized but highly active defect-rich orthorhombic Nb2O5 by robust yet selective acid etching of a parent oxide followed by annealing. When the product is mixed with a modest, standard amount of carbon black and conducting binder, the resulting anode outperforms all the previously reported Nb2O5-based ones, having 253 mA h g−1at 100 mA g−1 (0.5 C) and 130 mA h g−1 at 20,000 mA g−1 (100 C, taking less than 36 s to charge or discharge). With a reasonable tap density of 1.3 g cm−3, its cyclic performance is especially outstanding, having a stable capacity, e.g., 176 mA h g−1 at 25 C (5,000 mA g−1), over 4,000 cycles. Therefore, our Nb2O5 could be a very attractive alternative to commercial high-rate Li4Ti5O12 anode (170 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C, 130 mA h g−1 at 20 C, 80 mA h g−1 at 80 C) (Wang et al., 2015) as a durable high-rate power source in practical applications.

Results

Synthesis and Physicochemical Property

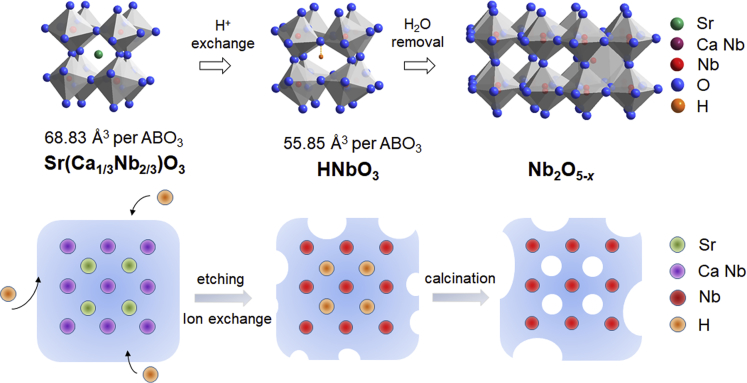

The precursor Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 is an ABO3 perovskite that also comprises a network of corner-sharing BO6 octahedra. It was chosen because Sr and Ca, being more basic than Nb, can be easily etched away in acid to remove all the A-site Sr and B-site Ca, hopefully leaving behind an intact yet atomically loose/open framework (Figure 1). Acid etching, however, introduced H into the framework by ion exchange, forming HNbO3 (Figure 1), but H can be driven away later by calcination. The diffraction peaks (Figure 2A) of our Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 match well with those of disordered Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 (JCPDS 17-0174), but they are slightly shifted toward higher angles indicating a 1.73% smaller unit cell (202.16 Å3 vs. 205.73 Å3). The diffraction peaks of HNbO3 also find good correspondence with those of perovskite HNbO3 (JCPDS 36-0794), but the unit cell is 3.92% larger in our material (465.04 Å3 vs. 446.82 Å3). Overall, the per-formula volume shrinks by 18.8% from 68.83 Å3 in Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 to 55.85 Å3 in HNbO3, which suggests large internal strains left in HNbO3.

Figure 1.

Synthesis Schematic

Structure: chemical evolution toward Nb2O5-x.

Figure 2.

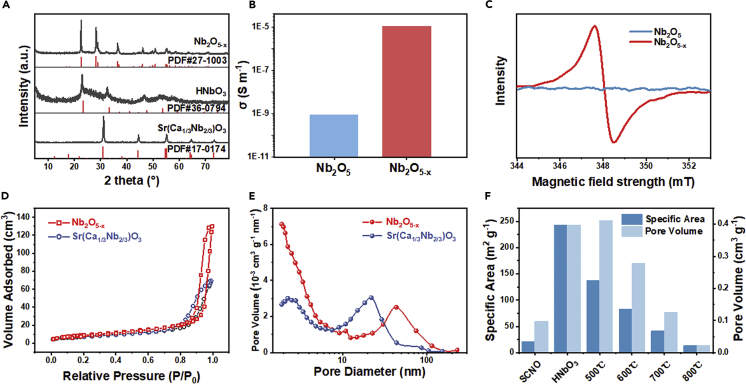

Physical Properties of Nb2O5-x

(A and B) (A) XRD patterns of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3, HNbO3, and Nb2O5-x. There is no indication of superlattice reflection in Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 due to B-site ordering, which if present occurs at about 19°. The lattice parameter of Nb2O5-x {a = 6.171973 Å, b = 29.287891 Å, and c = 3.931551 Å} are nearly the same as that of JCPDS: 6.168 Å, 29.312 Å and 3.936 Å; see Rietveld refinement result in Figure S3; (B) conductivity of air-annealed Nb2O5 and Ar-annealed Nb2O5-x.

(C–E) (C) EPR spectra of Nb2O5-x and Nb2O5; (D) nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms; and (E) BJH adsorption pore size distribution analysis of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 and Nb2O5-x.

(F) Specific area and pore volume of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 (noted as SCNO); HNbO3; and 500°C-, 600°C-, 700°C-, and 800°C-annealed Nb2O5-x.

We believe one cause of such large internal strains is the reconstitutive nature of the acid-etch/ion-exchange process. Here, by reconstitution, we mean a compositional modification at the level of local atomic structure that is repeated throughout the entire crystal, yet this is accomplished without reconstructing the overall microstructure or the size/shape of the crystal. This is supported by the SEM images showing almost the same size distribution and morphology for Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 (Figure S1A) and HNbO3 (Figure S1B), indicating reconstitution at the unit cell level does not involve crystallite dissolution/reprecipitation that will most certainly result in a rather different morphology and size. Indeed, when a higher concentration of HCl and a longer reaction time were used, dissolution/reprecipitation did take place, producing larger, hexagonal platelets as shown in Figure S1E.

As HNbO3 is heated, it dehydrates at above 200°C, and such process is mostly complete by 400°C according to TGA (Figure S2A). Annealing at 700°C under Ar gave the final product Nb2O5-x, which has the same structure as the Nb2O5 phase identified by JCPDS 27-1003 (Figure 2A) with nearly the same lattice parameters. Still, its particle size and morphology remain largely similar to those of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 and HNbO3 as shown in Figure S1C. Therefore, the entire process is most likely reconstitutive at the unit cell level and non-destructive at the single crystal level. Lastly, reheating Nb2O5-x in air to 800°C in TGA causes full oxidation (Figure S2B), from which we determined x = 0.61 although the accuracy of this value is likely to be compromised somewhat because the decomposition of hydroxyl residues may still persist to high temperature.

The Ar-annealed Nb2O5-x is black (Figures S4A–S4C), and it absorbs more light at longer wavelength outside the UV-absorption edge (Figure S4D UV-vis). Because x = 0.61 indicates the presence of Nb4+ or holes, one expects greatly improved conductivity over that of air-annealed Nb2O5, which is confirmed (1,000× higher) in Figures 2B and S5. In this respect, black niobia is analogous to black titania that also has greatly improved conductivity and enhanced light absorption compared with fully oxidized white titania (Chen et al., 2011, Chen et al., 2015, Cui et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2013a). Because of surface oxidation, XPS in Figure S6A reveals nearly the same Nb 3d spectrum as in white Nb2O5 in Figure S6B, with d3/2 and d5/2 peaks at respective binding energies of 209.8 eV and 207 eV typical for Nb(V)-O bonds in Nb2O5. (Near the baseline, the two small peaks at 208.4 eV and 205.6 eV in Figure S6A could be assigned to Nb(IV)-O bonds.) A definitive differentiation between the two oxidation states comes from EPR in Figure 2C, which reveals prominently magnetic Nb in Nb2O5-x but not in Nb2O5. Again, very similar findings were reported for black and white titania: they can be easily distinguished using bulk-sensitive EPR but not surface-limited XPS (Wang et al., 2011, Wang et al., 2013b).

Adsorption-desorption isotherms of N2 identified distinct loops of type-IV isotherm (IUPAC classification) in all the samples (Figure 2D). A specific surface area of about 41.2 m2 g−1 was found for Nb2O5-x, twice that (20.8 m2 g−1) of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 (precursor) and three times the value of Nb2O5 (14.3 m2 g−1, Figures S6C and S6D). Compared with Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3, Nb2O5-x has more pore volume (Figure 2E) especially in the <5 nm region, although it also has pores of 40–50 nm that are larger than the 20 nm pores of Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3. This is not surprising in view of the defects and lattice vacancies created by acid etching. Further specific area and pore volume analysis found the etched product HNbO3 had the largest specific surface area (242.5 m2 g−1) and pore volume (0.3979 cm3 g−1), which represents a huge increase from those of the Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 precursor (20.8 m2 g−1 and 0.0978 cm3 g−1, respectively.) These values progressively decrease during Ar annealing as shown in Figure 2F, although the pore volume did initially increase at 500°C likely because of dehydration of HNbO3 that occurs below this temperature. Meanwhile, maximum conductivity is reached after ∼600–700°C annealing (Figure S5), presumably due to increased hole concentration. So the optimal temperature for electrochemical performance that relies on specific surface area, porosity, and conductivity should lie around 600–700°C as will be seen later in electrochemical testing.

Defect-Rich Porous Crystal

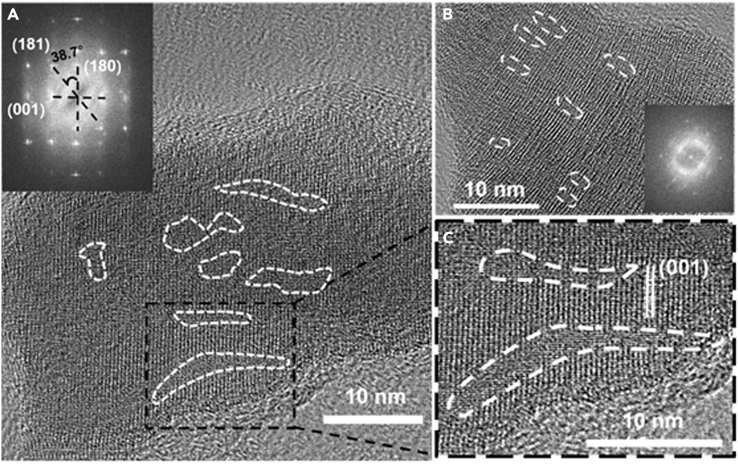

A detailed examination of nanoscale structure and defects was carried out on Nb2O5-x using TEM. First, we verified that each particle is a single crystal. Next, we have chosen to orient the crystal to be perpendicular to 001 and 180 as shown in Figure 3 because it was reported that Li insertion occurs most easily along these planes (Brezesinski et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2012, Kumagai et al., 1999). (See inset in Figure 3A, which is a fast Fourier transform of the image.) In this single crystal, there is very prominent diffuse scattering around (000) but not at (000), which is a distinct feature of displacement or alloying randomness. In our material, alloying randomness may arise from the random placement of filled and vacant sites, namely atoms and vacancies, on both the Nb and O sublattices. Such diffuse scattering is especially prominent in Figure 3A as indicated by streaking, likely due to displacement waves to accommodate copious vacancies. At the direct, atomic level, although the overall structure is clearly crystalline, there are numerous disordered regions, some arranged into bands of various thickness (many around 2–3 nm), length (varying from 3–20 nm), and orientations, as encircled by white dotted lines in Figures 3A–3C (Xie et al., 2017). (Disorder and nanopores are also obvious in HNbO3 in Figure S7, taken before high-temperature calcination.) This coexistence of order and disorder is especially evident in Figure 3B, and its extensive nature is highlighted in Figure 3C that is an enlarged view of one region in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Defect-Rich Nb2O5-x Crystal

HRTEM images showing coexistence of crystalline structure and extended defects. Insets in (A) and (B) are their fast Fourier transforms; (C) is a partially enlarged image of (A).

These disorders mostly likely originate from the interplay of (1) cation removal, from Sr, to Ca to H; (2) anion removal, from reduction; and (3) large changes in unit cell volume from Sr(Ca1/3Nb2/3)O3 to HNbO3 though not to Nb2O5-x, all the while maintaining the same octahedral framework and the same crystal construct over a length scale of the order of 100 nm, which is the (single crystal) particle size in Figure S1. This implies the creation of a large vacancy population and internal strains, the latter activating the former to collapse (most likely by cooperative shear that is known to be more expedient than diffusion) into vacancy clusters and stacking faults; some of these final, extended, vacancy-derived defects may provide paths for rapid Li transport as speculated in the literature (Come et al., 2014, Griffith et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2012, Kodama et al., 2006, Lubimtsev et al., 2013). They may also afford a wider variety of electrochemically active sites to facilitate fast-rate charging/discharging. Lastly, they may more easily accommodate volume changes upon Li insertion/extraction, thus helping to maintain structural integrity during electrochemical cycling.

Electrochemical Property and Performance

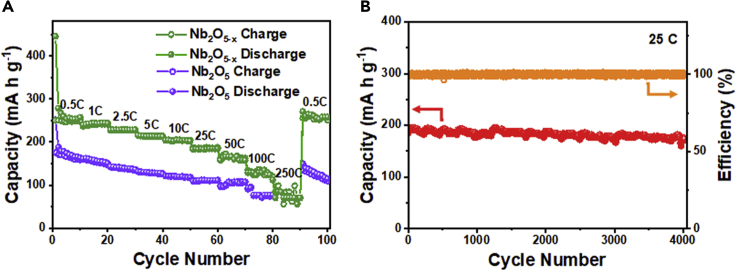

With Nb2O5 as a reference, the improved performance of Nb2O5-x is best illustrated using galvanostatic cyclic charge/discharge (CC) tests in Figure 4A for various charging rates. At 0.5 C, Nb2O5-x has a capacity of 253 mA h g−1, more than 50% higher than that of Nb2O5 (160 mA h g−1). This advantage is maintained at other rates, e.g., at 25 C (5,000 mA g−1), Nb2O5-x has 187 mA h g−1 vs. 105 mA h g−1 for Nb2O5. Even at the extremely high rates of 100 C and 250 C, Nb2O5-x still obtains 130 mA h g−1 (vs. 75 mA h g−1 for Nb2O5) and 70 mA h g−1 (Nb2O5's was too small to measure), respectively. In addition, because of the high cut-off voltage (1–3 V), we also used Al foil as a cheaper substitute for Cu-foil current collector and again obtained a very similar high capacity at high rates as shown in Figure S8. Superior reversibility and stability was also demonstrated by the CC tests, e.g., when the rate returned to 0.5 C at the end of the test, Nb2O5-x recovered 252 mA h g−1—the same as the initial value—whereas Nb2O5's capacity had by now faded to 112 mA h g−1 from the initial value of 160 mA h g−1. Outstanding reversibility and durability were further confirmed by extended CC tests at 25 C (Figure 4B): throughout the 4,000-cycle test, 100% coulombic efficiency was achieved, and the final specific capacity was 93.3% of the original. This represents a change of only 0.00167%/cycle, which is remarkable for an extraordinarily large capacity and high rate for this class of electrodes after relatively long cycling. In contrast, when long-term durability was achieved for other electrodes, it was usually with a much more limited capacity or shorter cycles. Examples are carbon/Nb2O5 composite at 70–80 mA h g−1 (charging/discharging rate not specified in this report) maintaining ∼87% after 70,000 cycles (Song et al., 2017), Nb2O5@graphene at 70–80 mAh g−1 at 50 C maintaining ∼70% after 20,000 cycles (Deng et al., 2018b), and urchin-like Nb2O5 at 131 mA h g−1 at 5 C maintaining 98% after 1,000 cycles (Liu et al., 2016a).

Figure 4.

High-Rate Capacity and Stability

(A) Rate performance of Nb2O5-x and Nb2O5; (B) cyclic performance of Nb2O5-x at a rate of 25 C (5,000 mA g−1).

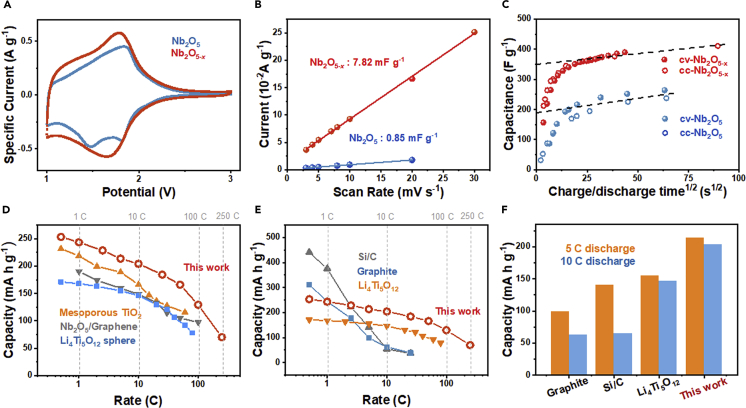

The CV profiles in Figure 5A confirm a larger current density for Nb2O5-x throughout the entire test range (also see Figure S9 for performance after other Ar-annealing temperatures). Note that its cathodic peaks are broader than Nb2O5's, which has two distinct peaks around 1.48 V and 1.79 V. This supports our expectation that copious defect sites in Nb2O5-x may offer a wider variety of electrochemically active sites for charging/discharging. To provide a more quantitative measure of this aspect, we used the CV test to measure the equivalent specific capacitance CL from dQ/dt = CLdV/dt, which is expected to hold in the voltage range away from any peak, such as from 2.9 V to 3 V in Figure 5A. As shown in Figure S10B, the CV profiles in this range collected at 3 to 10 mV s−1 give a current at 2.95 V that increases linearly with the voltage scan rate (Figure 5B), from which one obtains CL = 7.82 mF g−1 for Nb2O5-x vs. 0.85 mF g−1 for Nb2O5. Since the geometric surface areas of Nb2O5-x (41.2 m2 g−1) and Nb2O5 (14.3 m2 g−1) differ only by a factor of 3, the almost 10× difference in CL is a testament of more—or more active—electrochemical sites available per unit surface area in Nb2O5-x. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using the standard electrode configuration (Figure S11A) and the ion-blocking electrode configuration (Figure S11B) (Kanno and Murayama, 2001) also measured a (mostly electron) charge transfer resistance (Rct) at high frequency, 54.6 Ω for Nb2O5-x vs. 111 Ω for Nb2O5, and an ionic conductivity of 2.50×10−5 S m−1 for Nb2O5-x vs. a value too small to measure for Nb2O5. Lastly, the EIS results obtained using the standard electrode configuration allowed us to calculate a Li+ diffusion coefficient, which is 4.836 × 10−12 for Nb2O5-x and 7.547 × 10−13 cm2 s−1 for Nb2O5. (See Transparent Methods, which follows [Du et al., 2012] and data fitting, shown in Figure S12.) All these results are self-consistently supportive of Nb2O5-x's outstanding high-rate performance in conjunction with facile electron and ion transport.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical Properties and Performance Comparison

(A) Cyclic voltammetric profiles of Nb2O5-x and Nb2O5.

(B) Current as a function of scan rates for Nb2O5-x and Nb2O5 from CV curves in Figures S10A and S10B.

(C) Capacitance versus square root of half-cycle time in both CV test (solid symbols) from 0.5 to 100 mV s−1 and CC test (open symbols) from 0.1 to 20 A g−1. Extrapolated intercept capacitance is rate-independent capacitance k1, the remainder diffusion-controlled capacitance.

(D) Comparison of rate capacity between this work and three other anode materials reported in the literature (Liu et al., 2011, Sun et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2015).

(E and F) (E) Rate performance comparison between this work and three common commercial anodes, and (F) is their discharge capacities at 5 C and 10 C. (Li4Ti5O12 reference: Wang et al., 2015)

To further verify the above observations, we use a semi-empirical analysis to analyze the rate data from both the CV tests and the CC tests. In this analysis, we plot the data in Figure S13 against the scan rate v consistent with the following relation:

| I = avb |

Alternatively, we also plot the data against cycle time (Figure 5C) to be compared with the following relation (Lin et al., 2015):

| I = k1v + k2v1/2 or I/v = k1+ k2v−1/2 |

We obtain, for Nb2O5-x, b∼0.9 (Figures S13A and S13B) throughout the voltage range (1–2 V), and k1 = 349 F g−1 in Figure 5C in both the CV and CC tests. For diffusion-limited charge/discharge, b should be 0.5; for instantaneous, linear-capacitor-like charge/discharge, b should be 1.0, which is closer to the case here. Correspondingly, for rate-independent charge/discharge, k1 should account for the entire specific capacitance, overwhelming the diffusion-dependent contribution of the k2 v−1/2 term, which is again close to the case here. In comparison, for Nb2O5, while b is still comparable or slightly smaller than that for Nb2O5-x (Figure S13), its k1 = 214 F g−1 is considerably lower, indicating instantaneous linear-capacitor-like charge/discharge only makes a much smaller contribution. Specifically, we obtained the capacitor-like contribution of 58% for Nb2O5 compared with 87% for Nb2O5-x, which is extraordinarily high considering the fact that the well-celebrated pseudocapacitor, nanoparticle anatase TiO2 (Wang et al., 2007), features only 55% according to our experience (see Figure S14.)

Therefore, a consistent picture emerges for Nb2O5-x as an excellent electrode with unusually fast charging/discharging kinetics, thanks to very fast ion and electron transport and very plentiful electrochemically active sites. To put these results into perspective, we compare the rate performance of Nb2O5-x with some Nb2O5-composite and two high-rate anode materials (Li4Ti5O12 and TiO2) in Figure 5D; outperformance of Nb2O5-x is apparent. Compared with other commercial common anode materials, our electrode has a higher capacity at high rates (213 and 204 mA h g−1 at 5 C and 10 C, respectively) outperforming graphite, Si/C, and Li4Ti5O12 in Figures 5E and 5F. Although rate properties may be improved with delicate structural designs, as illustrated in hierarchical graphite wrapped Si—500 mA h g−1 at 5 C (Xu et al., 2017)—or by adding carbonaceous nano inclusions, e.g., in graphene-coated graphite—164 mA h g−1 at 5 C (Liu et al., 2016b)—these materials will have higher costs and lower tap densities, which adversely affects their practicality. In contrast, our Nb2O5-x is carbon free, has a reasonable tap density of 1.3 g cm−3, allows volumetric capacity of up to 328, 243, 169, and 91 mA h cm−3 at 0.5 C, 25 C, 100 C, and 250 C, respectively, to be achieved and has been mass-produced (we achieved kg level production), which all bode well for making it a promising practical anode material.

Mechanism Investigation

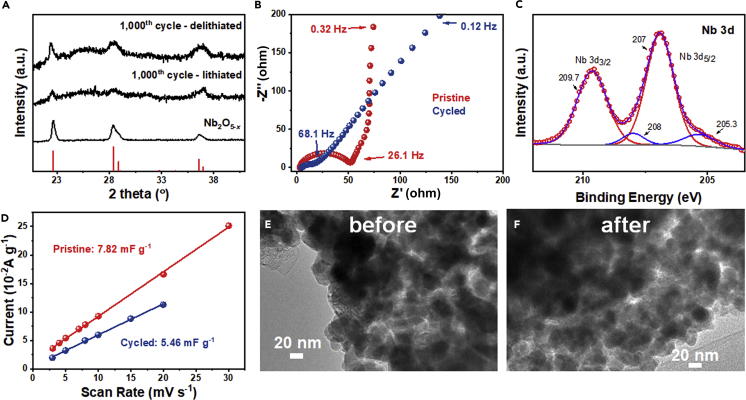

Lastly, to confirm the excellent endurance of Nb2O5-x anodes, we examined the Li-charged and the Li-extracted states after 1,000 cycles and compared them with those of pristine Nb2O5-x before cycling. Comparing their XRD (Figure 6A), we see despite peak broadening, crystallinity was maintained after cycling, indicating these sub-100 nm nanoparticles are structurally robust enough to withstand repeated Li-charging and extraction. Comparing their EIS (Figure 6B), although it has a lower slope closer to 45° at the low-to-intermediate frequency range after cycling, which is consistent with a more distributed resistive and capacitive character—perhaps caused by an increased frequency-dispersive conductivity (such as ion conductivity)—we see the charge transfer resistance is actually decreased by cycling. Comparing their Nb-3d XPS (Figure 6C vs. Figure S6A), we see cycling caused a significant increase of Nb (IV) compared with that in pristine Nb2O5-x (Figure S6A). Cycling, however, did cause a decrease in the equivalent specific capacitance CL (Figure 6D, constructed from the CV data in Figures S10B and S10C), which is perhaps indicative of a decrease in the electrochemically active area because the charge transfer resistance did not suffer from cycling. On the other hand, these results could also be consistent with Li trapping at the active sites in Nb2O5-x after insertion, which leads to internal strains (thus broadening of XRD), loss of active sites (hence a smaller CL), reduction of Nb (leaving Nb(IV)), and metal/ion conductivity (hence lower transfer resistance and battery-like charge storage EIS: in Figure 6B, pristine one from 26.1 Hz to 0.32 Hz; cycled one from 68.1 Hz to 0.12 Hz.). Of course, eventually, Li loss will deteriorate the Nb2O5-x electrode, which we did observe in past 4,000 cycles. Nevertheless, after 1,000 cycles, there was hardly any change in the microstructure according to TEM images (Figures 6E and 6F), attesting to the superior structural stability Nb2O5-x.

Figure 6.

Changes after Long Cycles

(A–F) (A) XRD patterns of as-prepared Nb2O5-x, Li-charged (1 V) and Li-extracted (3 V) Nb2O5-x after 1,000 cycles; (B) Nyquist plots of pristine and cycled Nb2O5-x; (C) XPS spectra of cycled Li-extracted (3 V) Nb2O5-x, with best fit for Nb(V) in red and Nb(IV) in blue; (D) current as a function of scan rates for pristine and cycled Nb2O5-x, its slope providing CL, and TEM images of Nb2O5-x electrode (E) before and (F) after 1000 cycles. (TEM samples prepared from powders scrapped off from the electrode.)

Discussion

-

1.

We have demonstrated that carbon-free defect-rich orthorhombic Nb2O5-x is an outstanding high-rate and durable LIBs’ negative electrode material, having an excellent capacity of 253 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C, 187 mA h g−1 at 25 C of which 93% is retained after 4,000 cycles, and 130 mA h g−1 even at 100 C, much better than the commercial high-rate anode Li4Ti5O12. Electrochemical kinetic analysis reveals that the energy storage is largely capacitive and non-solid-diffusion-limited in nature in this electrode.

-

2.

A chemical processing strategy based on selective etching has been developed to maintain the crystal size and morphology of precursor powders but systematically reconstitute their unit cell composition into one appropriate for the final orthorhombic Nb2O5-x. The huge strain involved in reconstitution is instrumental to the preservation of the high defect density that is critical for the uncommon electrochemical activity.

-

3.

The above finding and strategy may be applicable to other forms of Nb2O5-x and other oxides to enable high-performance new electrode materials. The simplicity and scalability of the fabrication method may allow large-scale industrial production.

Limitations of the Study

Although select etching as a synthesis method can be readily extended to many materials other than Nb2O5, it may be difficult to practice in doped materials if the dopant has a different chemistry from the main species. Etching is also likely to be sensitive to the surface structure, so the morphology of starting crystals could be critical. Future work is needed to define the universe of material composition and morphology suitable for this method.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National key R&D Program of China (Grant 2016YFB0901600), National Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 21871008 and 51672301), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (Grant 16JC1401700), and the Key Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. QYZDJ-SSW-JSC013).

Author Contributions

Z.L. and W.D. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.W. contributed to optimizing synthesis condition of Nb2O5-x. C.D. and Y.L. carried out TEM imaging. Z.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. I.W.C. and F.H. supervised the project and revised the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.100767.

Contributor Information

I-Wei Chen, Email: iweichen@seas.upenn.edu.

Fuqiang Huang, Email: huangfq@pku.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- Augustyn V., Come J., Lowe M.A., Kim J.W., Taberna P.-L., Tolbert S.H., Abruña H.D., Simon P., Dunn B. High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nmat3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezesinski T., Wang J., Tolbert S.H., Dunn B. Ordered mesoporous alpha-MoO3 with iso-oriented nanocrystalline walls for thin-film pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:146–151. doi: 10.1038/nmat2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu L., Yu P.Y., Mao S.S. Increasing solar absorption for photocatalysis with black hydrogenateed titanium dioxide nanocrystals. Science. 2011;331:5. doi: 10.1126/science.1200448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu L., Huang F. Black titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1861–1885. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00330f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Come J., Augustyn V., Kim J.W., Rozier P., Taberna P.-L., Gogotsi P., Long J.W., Dunn B., Simon P. Electrochemical kinetics of nanostructured Nb2O5 electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014;161:A718–A725. [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Zhao W., Yang C., Yin H., Lin T., Shan Y., Xie Y., Gu H., Huang F. Black TiO2 nanotube arrays for high-efficiency photoelectrochemical water-splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:8612–8616. [Google Scholar]

- Deng B., Lei T., Zhu W., Xiao L., Liu J. In-plane assembled orthorhombic Nb2O5 nanorod films with high-rate Li+ intercalation for high-performance flexible Li-ion capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28:1704330. [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Li M., Wang J., Jiang K., Hu Z., Chu J. Free-anchored Nb2O5@ graphene networks for ultrafast-stable lithium storage. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:185401. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aab083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., He W., Zhang X., Yue Y., Liu H., Zhang X., Min D., Ge X., Du Y. Enhancing the electrochemical performance of lithium ion batteries using mesoporous Li3V2(PO4)3/C microspheres. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:5960–5969. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith K.J., Forse A.C., Griffin J.M., Grey C.P. High-rate intercalation without nanostructuring in metastable Nb2O5 bronze phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8888–8899. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith K.J., Wiaderek K.M., Cibin G., Marbella L.E., Grey C.P. Niobium tungsten oxides for high-rate lithium-ion energy storage. Nature. 2018;559:556–563. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno R., Murayama M. Lithium ionic conductor Thio-LISICON: the Li2S-GeS2-P2S5 system. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001;148:A742–A746. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.W., Augustyn V., Dunn B. The effect of crystallinity on the rapid pseudocapacitive response of Nb2O5. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012;2:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama R., Terada Y., Nakai I., Komaba S., Kumagai N. Electrochemical and in situ XAFS-XRD investigation of Nb2O5 for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006;153:A583–A588. [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Zhang C., Zhang S., Wang J., Cai R., Lv C., Qiao W., Ling L., Long D. High-power and high-energy asymmetric supercapacitors based on Li+-intercalation into a T-Nb2O5/graphene pseudocapacitive electrode. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:17962–17970. [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Zhang C., Wang J., Qiao W., Ling L., Long D. Free-standing T-Nb2O5/graphene composite papers with ultrahigh gravimetric/volumetric capacitance for Li-ion intercalation pseudocapacitor. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11200–11208. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N., Koishikawa Y., Komaba S., Koshiba N. Thermodynamics and kinetics of lithium intercalation into Nb2O5 electrodes for a 2V rechargeable lithium battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999;146:3203–3210. [Google Scholar]

- Lin T., Chen I.W., Liu F., Yang C., Bi H., Xu F., Huang F. Nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon of extraordinary capacitance for electrochemical energy storage. Science. 2015;350:1508–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Bi Z., Sun X.G., Unocic R.R., Paranthaman M.P., Dai S., Brown G.M. Mesoporous TiO2–B microspheres with superior rate performance for lithium ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:3450–3454. doi: 10.1002/adma.201100599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Zhou J., Cai Z., Fang G., Pan A., Liang S. Nb2O5 microstructures: a high-performance anode for lithium ion batteries. Nanotechnology. 2016;27:46LT01. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/46/46LT01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Liu E., Chao D., Chen L., Liu S., Wang J., Li Y., Zhao J., Kang Y.-M., Shen Z. Large size nitrogen-doped graphene-coated graphite for high performance lithium-ion battery anode. RSC Adv. 2016;6:104010–104015. [Google Scholar]

- Lubimtsev A.A., Kent P.R.C., Sumpter B.G., Ganesh P. Understanding the origin of high-rate intercalation pseudocapacitance in Nb2O5 crystals. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:14951. [Google Scholar]

- Song M.Y., Kim N.R., Yoon H.J., Cho S.Y., Jin H.-J., Yun Y.S. Long-lasting Nb2O5-based nanocomposite materials for Li-ion storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:2267–2274. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b11444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Mei L., Liang J., Zhao Z., Lee C., Fei H., Ding M., Lau J., Li M., Wang C. Three-dimensional holey-graphene/niobia composite architectures for ultrahigh-rate energy storage. Science. 2017;356:599–604. doi: 10.1126/science.aam5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viet A.L., Reddy M.V., Jose R., Chowdari B.V.R., Ramakrishna S. Nanostructured Nb2O5 polymorphs by electrospinning for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:664–671. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Polleux J., Lim J., Dunn B. Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:14925–14931. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Wang H., Ling Y., Tang Y., Yang X., Fitzmorris R.C., Wang C., Zhang J.Z., Li Y. Hydrogen-treated TiO2 nanowire arrays for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Lett. 2011;11:3026–3033. doi: 10.1021/nl201766h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Yang C., Lin T., Yin H., Chen P., Wan D., Xu F., Huang F., Lin J., Xie X. H-doped black titania with very high solar absorption and excellent photocatalysis enhanced by localized surface plasmon resonance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:5444–5450. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Yang C., Lin T., Yin H., Chen P., Wan D., Xu F., Huang F., Lin J., Xie X. Visible-light photocatalytic, solar thermal and photoelectrochemical properties of aluminium-reduced black titania. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2013;6:3007–3014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Wang S., He Y.-B., Tang L., Han C., Yang C., Wagemaker M., Li B., Yang Q.-H., Kim J.-K. Combining fast Li-ion battery cycling with large volumetric energy density: grain boundary induced high electronic and ionic conductivity in Li4Ti5O12 spheres of densely packed nanocrystallites. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:5647–5656. [Google Scholar]

- Wei M., Wei K., Ichihara M., Zhou H. Nb2O5 nanobelts: a lithium intercalation host with large capacity and high rate capability. Electrochem. Commun. 2008;10:980–983. [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zhang X., Zhang H., Zhang J., Li S., Wang R., Pan B., Xie Y. Intralayered Ostwald ripening to ultrathin nanomesh catalyst with robust oxygen-evolving performance. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1604765. doi: 10.1002/adma.201604765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Li J.Y., Sun J.K., Yin Y.X., Wan L.J., Guo Y.G. Watermelon-inspired Si/C microspheres with hierarchical buffer structures for densely compacted lithium-ion battery anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7:1601481. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.