Abstract

Although we know much about demographic patterns of smoking, we know less about people’s explanations for when, how and why they avoid, develop, or alter smoking habits and how these explanations are linked to social connections across the life course. We analyze data from in-depth interviews with 60 adults aged 25-89 from a large southwestern U.S. city to consider how social connections shape smoking behavior across the life course. Respondents provided explanations for how and why they avoided, initiated, continued, and/or quit smoking. At various times, social connections were viewed as having both positive and negative influences on smoking behavior. Both people who never smoked and continuous smokers pointed to the importance of early life social connections in shaping decisions to smoke or not smoke, and viewed later connections (e.g., marriage, coworkers) as less important. People who quit smoking or relapsed tended to attribute their smoking behavior to social connections in adulthood rather than early life. People who changed their smoking behavior highlighted the importance of transitions as related to social connections, with more instability in social connections often discussed by relapsed smokers as a reason for instability in smoking status. A qualitative approach together with a life course perspective highlights the pivotal role of social connections in shaping trajectories of smoking behavior throughout the life course.

Keywords: Life course analysis, Qualitative methods, Smoking, Social relationships, Transitions

Introduction

Smoking behavior is patterned over the life course, with smoking often initiated early in adolescence but diminishing as people transition into their adult roles (Chen & Jacques-Tiura, 2014; CDC, 2011). Survey research indicates that social connections are key predictors of a person’s smoking behavior. Being in social networks with people who smoke increases a person’s risk of smoking (Christakis & Fowler, 2008), and the emergence of new social relationships—such as getting married—impacts smoking decisions (Freeh, 2014). But these patterns reveal little about when, how, and why social connections shape whether people smoke. Furthermore, smoking behavior can be dynamic throughout the life course, but we know little about the motivation for transitions in and out of smoking or how they may be linked to social connections. In this study, we pair a life course perspective—which emphasizes that smoking is a dynamic behavior that may shift in response to life course transitions and social connections (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003)—with qualitative methods to ask how social ties influence the avoidance, initiation, continuation, cessation, and relapse of smoking behavior throughout the life course. Using this approach, we aim to describe the key mechanisms through which social ties may influence smoking at different points in the life course.

We analyze qualitative data from in-depth interviews with 60 men and women age 25 to 89 from a large southwestern U.S. city to describe the roles that social connections play in influencing smoking behavior, according to respondents’ own narratives and explanations. Qualitative analysis—through its emphasis on subjective perspectives of one’s personal life history—is an effective method to address key questions about behavioral change across the life course (Hollstein, 2018; Reczek et al., 2014). Our focus is on social connections, but our analysis draws on several important tenets of the life course framework to provide insight into the processes behind change or persistence in smoking behavior over the life course. Each interview provides a detailed narrative about the social factors influencing one’s smoking trajectory over the life course, allowing us to explore the respondents’ own descriptions of how social connections foster each of four distinct smoking trajectories—never smokers, former smokers, relapsed smokers, and continuous smokers. We find that social connections in early life (e.g., parents, church connections, high school friends) are viewed as most important for the smoking trajectories of never smokers and continuous smokers, whereas people who quit smoking or relapse cite being primarily motivated by changing social connections in adulthood (e.g., new job bringing new co-workers, ending intimate relationships). Descriptions of the personal motivations to smoke or not within the context of social connections and changes in those connections can offer new strategies for thinking about how to reduce smoking at different points in the life course.

Background

Linked Lives and Smoking

The life course framework conceptualizes individual lives as characterized by life events and trajectories that unfold over time, are connected to others, and are embedded within influential social contexts (Elder et al., 2003). Life course perspectives depart from individualistic conceptualizations of smoking that emphasize personal dispositions and instead emphasize the interplay between individuals. We focus primarily on the life course principle of linked lives, which states that people’s life trajectories intersect and interact with the life trajectories of their salient social connections in mutually influential ways (Carr, 2018). Thus to understand an individual life course, we must also consider it in relation to people’s social connections. We argue that the concept of linked lives within a life course perspective is a powerful tool for describing how social connections serve as mechanisms for smoking behavior.

The linked lives principle recognizes that individual lives are embedded within broader social networks (Carr, 2018). These broader social networks, in turn, influence health behavior decisions—including decisions about smoking. These decisions about smoking or abstaining from smoking are tied to the smoking behavior of family members, peers, and other social connections throughout life (Christakis & Fowler, 2008; Kreager, Haynie, & Hopfer, 2013). Smoking is highly relational across the life course and influenced by many different social connections, but there is variation in the extent to which connections (e.g., spouse, peers, parents) are influential, with this depending on life course stage (Haas & Schaefer, 2014). Although the linked lives concept primarily refers to close social connections, we suggest that linked lives should also include less close relationships, such as those with neighbors and coworkers, as these social connections likely also matter for health and well-being (Erickson, 2003).

Social connections can be both beneficial and detrimental for health and health behavior, depending on the context, and can have powerful influences on health behavior (Umberson, Liu, & Reczek, 2008). Most explanations for the mechanisms through which social connections shape health behavior—such as smoking—focus on social support, social strain, contagion, and social control. Social connections can provide social support (i.e., the perception that one is loved and cared for; Thoits 2011), which can empower people in their health decisions to abstain from or quit smoking. Social support can also include instrumental or financial support, providing practical resources (e.g., funds for nicotine patches) to help individuals quit smoking. Yet social connections can be a source of relationship strain or stress, and smoking can be a way to cope with that stress (Umberson et al., 2008). For example, one study found that young women who smoked rated relationship stress as the primary reason for their smoking (McDermott, Dobson, & Owen, 2006). Regarding contagion, social connections may model smoking behavior, sometimes initiating a process of smoking contagion that helps explain why those surrounded by smokers often start smoking and have difficulty quitting (Margolis & Wright, 2015). And finally, smoking is impacted by social control processes (i.e., attempts to monitor and regulate another’s health behavior and internalization of norms and meanings that influence health behaviors), which can discourage smoking depending on the salience of those ties (Umberson, Donnelly, & Pollitt, 2018).

Human Development, Life Course Transitions and Smoking

To put these social connections into further context, we also draw on the life course principles of human development and aging and turning points and transitions (Wethington, 2005). First, according to the human development and aging principle, health outcomes reflect lifelong processes, influenced by early life experiences and evolving through subsequent life stages (Broms et al., 2004). Individual smoking behavior is dynamic (e.g., some people avoid smoking throughout their life, others start and stop) and occurs in relation to broader social connections and changes in those connections. Although most people who smoke begin during adolescence or young adulthood (Chen & Jacques-Tiura, 2014), some people initiate in childhood and others later in life, perhaps in response to changing social circumstances. Survey methods typically divide smoking behavior into three categories that include current smokers, former smokers, and never smokers (Lariscy, Hummer, & Hayward, 2015; Nelson et al., 2018), but this approach treats smoking as a relatively stable activity and misses shifts in and out of smoking and when, why, and how these shifts occur. Additionally, survey methods often focus on a narrow age range (e.g., adolescents; Cheetham et al., 2015), but this overlooks social connections across the life course and how they shape smoking trajectories (e.g., how social connections in adolescence impact smoking behaviors in late adulthood). A qualitative life course analysis with attention to human development and aging allows us to analyze how smoking trajectories unfold in relation to social connections over time and how social connections can influence smoking trajectories as they ebb and flow.

Second, transitions or turning points in the life course can lead to change in health behavior because life transitions often introduce new social connections, as well as new norms, responsibilities, stressors, and sanctions depending on the salience of these ties (Freeh, 2014; Pampel, Mollborn, & Lawrence, 2014). Transitions can be major or minor changes in social roles or responsibilities, whereas turning points reflect major changes in ongoing social role trajectories (Wethington, 2005). Both are typically tied to changes in social connections. Some transitions and turning points—such as the birth of a child—are associated with lower rates of smoking, whereas others—such as divorce—are associated with increased smoking (Freeh, 2014).

Transitions and turning points may be more strongly linked to smoking when those transitions are stressful, as smoking is a coping mechanism as discussed above (Reczek et al., 2016). Social acceptance of smoking varies across life course stages, such that smoking in high school is somewhat acceptable, whereas smoking as a new mother is highly stigmatized (Stuber, Galea, & Link, 2008). As individuals transition to adulthood, they often draw on their social understandings of what it means to be an adult and change their behavior to conform to these meanings (Andrew et al., 2006). This might lead to changes in smoking behavior but the literature is limited in identifying the key mechanisms giving rise to these changes over the life course.

Present Study

By using these life course tenets to guide a qualitative analysis of smoking trajectories in relation to social connections over the life course, our approach allows a dynamic and nuanced description of smoking avoidance, cycles of cessation and re-initiation, and trajectories of smoking more generally. We analyze the smoking behaviors of adults from a wide range of ages and explore how and when social connections are seen as influential for smoking behavior, distinguishing between multiple smoking trajectories. We also consider whether the key mechanisms linking smoking and social connections vary over the life course. Our research goal is to develop a rich description of respondents’ narratives of how social connections are connected to their smoking behavior (see Umberson and Reczek 2007 for example of this approach).

Methods

We analyzed data from 60 in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted between 2008 and 2009 with Institutional Review Board approval in a large southwestern U.S. city. When these interviews were conducted, 20.6 percent of people in the U.S. currently smoked cigarettes, and in the region where we conducted these interviews, the rate was similar (19.2 percent) (CDC, 2011). The main purpose of the interviews was to obtain narratives on how social connections were related to health behavior from childhood through adulthood. We used a recruitment strategy with quotas based on gender, race/ethnicity, and age in order to obtain equal numbers of Black and White men and women in the sample (15 people in each racial/gender group), equally across several age groups ranging from 25 to 89 years. Our sample allowed us to consider change across the lifespan, through both retrospective perspectives (e.g., 80-year-old respondent discussing adolescence, early adulthood, and midlife) and contemporary perspectives (e.g., 30-year-old respondent discussing early adulthood). To recruit respondents, we posted flyers in racially and socioeconomically diverse areas of the city, sent out calls for participants to local professional and community-based email listservs, developed various organizational contacts, and conducted snowball sampling. The average household income of the sample was $45,246 (range: $7,000–$110,000). The majority of respondents had undergraduate degrees (n=40); 7 percent had a high school diploma or less, and 27 percent had attended some college. Most respondents were currently unmarried (37% divorced, 22% never married, 7% widowed).

Interviews lasted an average of 1.5 hours and were recorded in the respondent’s home or at university offices, then professionally transcribed. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents. Respondents described their health behaviors from childhood to the present day and the factors they thought influenced those health behaviors. With regard to smoking, respondents were asked a series of questions, starting with, “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?” If respondents did not smoke, they were asked why they avoided smoking. Those who had smoked were asked about their smoking history. The interviewer asked follow-up questions regarding the role of certain life transitions, relationships, or other social contexts in shaping smoking. Respondents who quit smoking were asked when and why they quit. All respondents were asked about the smoking behaviors and attitudes of key people in their life (e.g., parents, children, intimate partners) and how those key people’s habits may have influenced the respondent’s own habits. Respondents were asked their views on smoking, from childhood through present-day.

We took a multi-staged standardized approach to qualitative data analysis that emphasized the dynamic, systematic, and flexible construction of codes for the purpose of developing analytical interpretations (Deterding and Waters 2018). Our goal was to broadly describe the variant ways in which social connections are interpreted as influencing four smoking trajectories: never smokers, former smokers, relapsed smokers, and continuous smokers. In line with an abductive approach (Tavory and Timmermans 2014), we identified conceptual categories as they emerged from the transcripts, and we also used key life course tenets to guide both the construction of questions and the analysis to identify major themes from the data. We read the transcripts two or more times to ensure understanding of the content of the interviews, and used a three-step coding process. First, focusing primarily on the sections related to smoking, we conducted line-by-line categorization of textual data in order to summarize data, developing a standardized codebook from these initial coding schemes to analyze data during subsequent analytic stages. Second, we developed focused categories specifically related to smoking by connecting initial line-by-line codes. During this stage, general descriptions of how, when, and why people initiated, quit, and continued smoking at the broadest conceptual level were identified. Identifying how respondents thought that social connections mattered for their own health habits across the life course was a key goal of our interview guide, and thus social connections were a clear primary explanation for smoking behavior in our analysis. We identified codes specifically related to smoking and social connections and relied on these for the remainder of the analysis. Codes related to smoking but not related to social connections were identified, but comprised a small number of codes and were beyond the scope of this project. In the third and final stage of analysis, we examined how these descriptive categories related to one another, systematically analyzing how focused codes formed patterns in the data across the sample. We conducted this analysis with the aid of QSR International’s NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software. Descriptive codes were analyzed in connection with concepts related to linked lives, human development, and life course transitions or turning points. Themes and subthemes were developed from this final stage of analysis, as detailed below in the Results. Saturation, defined as “the point when a researcher confirms a pattern of findings” (Roy, 2012: 661), was achieved when no new themes regarding smoking and social connections emerged and when data for existing themes and connections across themes were sufficient in terms of both depth and breadth.

Results

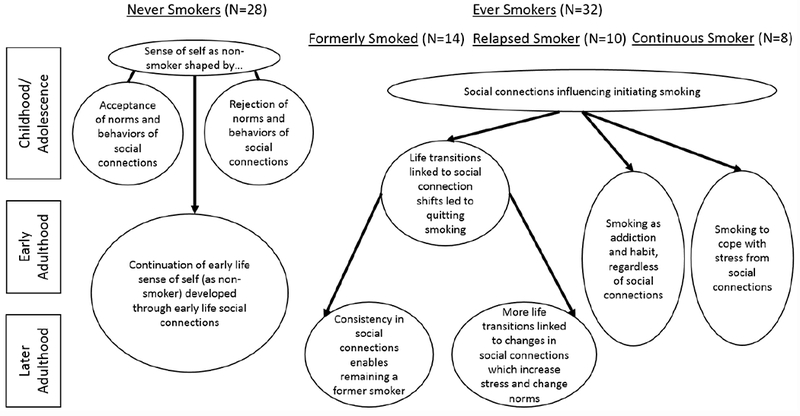

Respondents fell into four general categories: never smokers, former smokers, relapsed smokers, and continuous smokers. Within each of these categories, respondents provided explanations for how they avoided, initiated, continued, or quit smoking throughout their life, and these explanations tended to relate to social connections at different life stages. These categories and predominant explanations at different life course stages (i.e., childhood/adolescence, early adulthood, later adulthood) are summarized in Figure 1, along with the number of respondents within each category. Explanations for avoiding smoking largely related to a respondent’s sense of self that developed within social connections (e.g., parents, church community) in childhood, whereas reasons provided for initiating smoking related to social connections in childhood and early adulthood. Among smokers, those who successfully quit said they did so primarily due to transitions in their life related to social connection shifts (e.g., new spouse, parenthood) that remained stable. Those who quit smoking and then began again typically associated this relapse with life transitions related to social connection shifts (e.g., new colleagues at work, divorce) that were typically temporary and transient. Finally, respondents who still smoked and never quit referenced reasons linked to social connections in adulthood (e.g., stress from intimate relationships) but also the importance of habit and addiction.

Figure 1:

Smoking Categories and Explanations of Smoking Trajectories and Transitions Across the Life Course (N = 60)

Never Smokers

Almost one half of the respondents never smoked. Avoiding smoking was due to a multitude of factors, but central were reasons related to respondents’ own sense of self created within social connections in childhood and adolescence. This “non-smoker” sense of self was viewed as permanent and was reinforced through social factors in childhood including linked lives with family members and religious ties.

Acceptance of norms and behaviors of social connections.

Several (n=13) never-smoking respondents said they avoided smoking because not smoking was part of their family culture, often emphasizing that they had no family members who smoked. Mary (woman, age 43) described why she was never interested in smoking— “Smoking is really not something we do in my family.” For never smokers, the immediate family was most important and sometimes conflicted with extended family or friends. Matthew’s (man, age 25) grandmother smoked heavily, and when she had a stroke, he said his parents “would always just say what happened to my grandmother” to caution him not to smoke. When pressured by friend to smoke, he drew on his family culture and history and his identity as a non-smoker to continue avoiding smoking. The non-smoker identity established in childhood within his family of origin continued to be influential throughout Matthew’s (and other non-smoking respondents’) life course.

Never smoking was also related to social connections within extra-familial communities (n=6), especially the values and norms within religious subcultures. These values and norms typically related smoking to something immoral, reckless, and irresponsible, done by other people but not people within their own community. Mabel (woman, age 54) said her family did not smoke, because “my family was a Christian family and drinking and smoking was not looked as something that responsible people do.” Other respondents referenced a general worldview held by their community wherein smoking was immoral. Beverly (woman, age 58) referred to social comparisons in her high school peer group when explaining why she never smoked:

“But if a girl smoked, it was, you were kind of thought of as being kind of loose, kind of like wow, she’s, you know, not a very nice girl. So, I looked at smoking as an evil, something I didn’t want to do.”

Beverly continued to avoid smokers as an adult, and said that when she found out a cousin smoked, “I went and bought a ‘Thank You For Not Smoking’ sign and put it outside of my house by the front door” to discourage that behavior in her home. For Beverly and some other never smoking respondents, views on smoking developed early in life within the immediate family context or church community trumped extended family ties or relationships formed later in the life course, with a non-smoking identity even keeping relationships with smokers from forming or deepening.

Rejection of norms and behaviors of social connections.

Many of the never smoking respondents (n=15) described how their non-smoking status was borne out of a rejection of the smoking behavior of social connections in their lives—namely those of family members. Karen’s (woman, age 42) father and husband were heavy smokers and her mother an occasional smoker. But she stood apart, saying:

“I have always been one of those people. I never really gave into peer pressure, social pressure…I have always been that way even in high school. My friends were smoking and doing this and that and I was like, okay.”

She resented her husband for his smoking, noting that he did not even take it outside like her father did, and she complained about having to “endure [his] smoke in the house.” Karen developed a strong distaste for smoking, and saw her own non-smoking as a rejection of the smoking of her closest social connections.

For Karen and some others, this rejection of smoking was largely about being repulsed by smoking—especially the smell. Anna (woman, age 52) said she “hated” smoking and blamed her grandmother, saying:

“[She would] blow smoke in my face. I couldn’t stand the smell and I have had asthma on and off. I just couldn’t stand it. Didn’t want to be around it. Never had a cigarette in my mouth ever.”

These memories of the physical discomforts of secondhand smoke persisted into adulthood. Although Anna married a person who smoked and had friends growing up who smoked, she always avoided it. She even insisted her husband never smoke in their home and said she “would not even drive in my car if it was smoky.”

But, for most never smoking respondents, rejection of the smoking behavior of family members was primarily linked to cautionary tales of family members whose health was harmed from smoking (n=9). Margie (woman, age 70) described with her parents:

“Both smoked my whole life. My mother smoked until her last—until she broke her hip. That was six weeks before she died. My dad smoked until he was diagnosed with lung cancer and quit cold turkey and lived another eight years. I hated their smoking…I hated having to live with the smell of it.”

Margie’s revulsion to her parents’ smoking and concerns about their health contributed to her decision to never smoke. These explanations often worked in tandem, with the distaste for smoking as a sensory experience overlapping with health concerns based on family member’s experiences. Jerry (man, age 55) said he did not smoke, which was “so ironic because both parents smoke, but none of the children smoke and I think it was because we got tired of living in a haze.” He said, “After being in a room with smoke, there was no interest at all,” and he viewed people who smoked as “suicidal.” His first wife smoked but died of cancer, which he said confirmed everything he believed about smoking.

Continuation of early life sense of self (as non-smoker) developed through early life social connections.

As noted in the above sections and shown in Figure 1, for respondents who never smoked, there was a continuation of this early life sense of self as a non-smoker—whether from rejection of early life social connections’ smoking or acceptance of early life social connections’ non-smoking. The family environment was most central for never-smoking respondents. Respondents who never smoked viewed these early life experiences of adopting a non-smoking identity alongside their parents or other close groups or rejecting a smoking identity within their families as shaping their continued decision to avoid smoking throughout adulthood.

Smokers

We divided those who ever smoked into three categories: (1) respondents who successfully quit smoking by the time of the interview (former smokers), (2) respondents who cycled between smoking and not smoking multiple times (relapsed smoker), and (3) those who started smoking and never quit (continuous smoker). Although they had common themes in terms of initiating smoking, these groups then diverged in terms of whether they continued smoking, quit smoking, and/or began smoking again, and respondents within these categories identified different social factors as most notably shaping their smoking decisions.

Social connections influencing initiating smoking.

All but one of the “ever smoking” respondents reported initiating smoking because people in their lives who they were close to also smoked. (The only “ever smoker” who was an exception gave the explanation that he began smoking because of boredom.) These decisions to begin smoking were made within the context of smoking by immediate family members, friend networks in high school and college, and colleagues at work and in the military. Within these social spaces, respondents viewed smoking as cool, normative, and a way to be socially connected to people they valued. Typically, as with never smokers, these decisions to smoke began in late childhood or adolescence. Doug (man, age 55), who began smoking when he was 11, said, “I wanted to smoke. My dad smoked…It looked like it was cool.” Rose (woman, age 63) described the role of her peers in her decision to smoke: “I grew up into that time period I thought it was kind of cool to have long fingernails and a cigarette.” Thomas’s (man, age 35) offered a similar explanation, recalling that he smoked to gain acceptance with the other smokers at school. Although social connection early in life emerged as the primary motivation for smoking initiation, smokers’ reasons diverged in terms of why they continued smoking, quit smoking, or relapsed.

Former Smokers

Former smokers comprised the second largest category, behind never smokers. Those who successfully quit often did so because of significant turning points and transitions, which then led to shifts in their social connections that were viewed as significant for their smoking behavior, especially the cultural and behavioral norms around smoking within these networks. For many of these respondents (n=8), these shifts included losing the social connections who had been part of the motivation for initiating smoking. The most commonly described life transitions were entry into new intimate relationships, the dissolution of intimate relationships, entering parenthood (especially becoming pregnant), and the social environment of employment changes.

Life transitions linked to social connection shifts led to quitting smoking.

Most often (n=6), smoking transitions were linked to shifts in intimate relationships, facilitating long-term smoking cessation. These shifts included both beginning new relationships (with non-smokers) and ending old relationships (with smokers). Kimberly (woman, age 51) began smoking at 19, describing how she “was in a relationship with someone who was smoking so I started smoking. I mean how dumb is that?” Once she began smoking, her social network was primarily comprised of other smokers, and quitting smoking became a way for her to distance herself from her family and those friends from young adulthood and establish a new adult self. She said memories of her father smoking “actually ended up shaping my decision not to smoke because, I mean, in an effort to kind of reject some of those things from childhood.” Kimberly’s experience exemplified how non-smoking respondents sometimes rejected smoking habits among those in their family of origin.

Respondents also identified social connection shifts related to employment changes and religious conversion, although these were discussed less often than intimate relationship shifts. Thomas quit smoking because of his new job at a school, noting:

“I work with a lot of kids. I really look at it like, okay, that was one reason I quit smoking actually because I can’t be in close proximity with a kid and be any kind of positive influence if I just reek like a pack of Camel’s.”

Paula (woman, age 42) said she quit smoking because of spiritual reasons pressure from others in her congregation: “I had become a Christian and I had decided that that wasn’t in accordance with the lifestyle of a Christian so I decided to stop smoking.” Likewise, Billy (man, age 52) said he smoked for much of his life but credited his success quitting largely to religious connection:

“As I’ve gotten older, now I know that I have to have God in my life, and I have to be more responsible. And all those things I used to do are not important to me no more. I don’t drink today. I don’t smoke. I don’t do drugs. I don’t do anything. I consider God. I read my Bible and study. I pray. I go to AA meetings. I’m responsible. I don’t go to clubs, just church.”

Paula and Billy’s new religious status changed where they spent their time, who they spent time with—such as in AA meetings for Billy, and how they think of themselves. This is reminiscent of the themes among non-smokers who chose to avoid smoking due to the norms and values of their religious communities.

Relapsed smokers (described below) also discussed how shifts in social connections and environments contributed to them temporarily quitting smoking, but former smokers tended to credit consistency in social connections as the reason they did not relapse. Former smokers often described fairly stable social environments, especially moving forward from early adulthood to later life, providing a more ideal situation in which to continue smoking avoidance after previously smoking.

Relapsed Smokers

Among the relapsed smokers, some no longer smoked at the time of the interview but thought they might start again, whereas others had quit but begun again. We also call this group “on-and-off smokers.” As with those who quit, for most in this group, the cyclical nature of their smoking reflected life transitions, most notably changes in social connections brought on by marriage, children, school, or work. These life transitions were also accompanied by changes in norms as well as increases in stress levels tied to these relationships, which some respondents coped with through smoking and then quit smoking when relationship stress decreased or the relationship ended. Family transitions, and the related stress or normative expectations, were the most common reasons given for cycling in and out of smoking.

More life transitions linked to changes in social connections which increase stress and change norms.

Most relapsed smoking respondents (n=8) pointed to stress due to major life transitions prompting changes in their social connections as the reason they began smoking again. Audrey (woman, age 41) started smoking at age 14, describing how it was “a self-destructive kind of thing I would do if I was drinking or if I was hanging out with certain friends who smoked.” During college, when she was no longer around friends who smoked she quit, but she started again and smoked more regularly after graduating. She described how moving near a friend who chain smoked was key:

“She and her husband were intense smokers and so, just in hanging out, I started smoking and I unfortunately got this very positive association with smoking really heavily which was the result of processing stuff and the camaraderie in connection with this great friend.”

Her next smoking transition occurred after she married a man with asthma, and she reduced her smoking to only the weekends. She said she would smoke “an entire pack in like three hours, and then I would feel completely violently ill on Saturday and Sunday from smoking all the cigarettes so then I wouldn’t have them again for the rest of the week.” After they divorced, she reported for four to six months before she quit again.

Similarly, Meredith’s (woman, age 54) experience was also linked to her relationship history and accompanying stress levels. She began smoking when she was 15 years old, but, after marrying in her 20s, she quit, because “[her husband] didn’t smoke and he didn’t kiss me very much and I thought maybe that’s why he’s not kissing me.” When they divorced, she began smoking again: “It was like, ‘I’m not married to you anymore. I’m going to smoke and I know it annoys you and it makes me want to do it even more.’” During this stage of life, she described quitting a few times for her health, but started again because her friends smoked. Marriage and divorce not only shifted stress levels but also the social context around smoking and smoking norms, contributing to instability in smoking choices. For Audrey, Meredith, and other relapsed smokers within this subtheme, educational transitions, friendship changes, and intimate relationship transitions were all accompanied by various stress levels, which either facilitated quitting smoking or re-initiating smoking.

Wanting to improve health and avoid serious health problems were also motivations for trying to quit for some respondents (n=8), but this was sometimes undermined by social connections who smoked or social environments—often the workplace—where smoking was common or stress levels were high. George (man, age 47) quit smoking for three years after a heart attack, but he began again during a stressful time when he was cast in a local play. He said during rehearsal one day, “I just followed [other cast members] out the door and without even asking I took a cigarette out of one of their hands and said, ‘This one’s mine.’” He said he continued smoking because “it seems to calm me down.” Thus his attempts to quit were undermined by his social connections, largely comprised of smokers, and job-related stress.

This difficulty to quit was also attributed by some respondents (n=2) to be due to the addictive nature of cigarettes, with this occurring alongside factors that contributed to respondents desiring to quit. Jim (man, age 68), who had his first cigarette at 6-years-old and became a steady smoker at 13, had a heart attack in his 50s, requiring open heart surgery. He said, “My family physician and, I think, my cardiologist too, both contend that my smoking contributed greatly to the heart problems.” He attempted to quit smoking because of concerns about his health, yet he could never successfully quit,

“I’d stop for a little while but I couldn’t quit. I have heard some psychologists or psychiatrists say that it’s easier to quit heroin than it is smoking. That stuff is highly addictive the way they do it now. And I’d slip back into it a little, then quit for a while, and slip back into it.”

This theme of addiction was most prominent in the final group, the current smokers who had never quit.

Relapsed smokers attributed their “on-and-off’ smoking behaviors to shifting social contexts, with this primarily seen as impacting their levels of stress. In contrast with former smokers, their social contexts and relationships were fairly unstable. And in contrast with continuous smokers, discussed below, relapsed smokers saw their smoking as fairly sensitive and reactionary to these shifts in social relationships. Decisions to smoke and not smoke were linked to stress within these shifting relationships, as well as changes in norms and values around smoking.

Continuous Smokers

Just as social connections led to smoking initiation, quitting, and restarting, social connections also contributed to smoking persistence, especially when they involved chronic stress. Continuous smokers’ reasons for smoking were most often linked to social connections in early life, but these respondents saw themselves as unable to quit and this inability as mainly driven by individual-oriented factors, namely ingrained habit or addiction, and present-day stressors. These addictions were so powerful that respondents viewed them as uninfluenced by their current social connections, including the people in their lives who tried to get them to quit smoking. Almost all in this group began smoking despite strong incentives to avoid it and continued despite sometimes being the only smoker in their social network.

Smoking to cope with stress from social connections.

Every continuous smoking respondent said that smoking was a way to cope with stress, and the majority (n=7) specifically pointed to relationship stress (e.g., marital stress, caregiving stress). Gail (woman, age 61) viewed smoking as a better way to self-medicate in response to stress, which was especially high with multiple caregiving responsibilities: “My mother and father had started having a few problems with their health and I was trying to run back and forth, taking care of my kids and all that.” Smoking seemed safer to Gail than other options: “My nerves were kind of bad and so I said, ‘Well, I can’t go through life drinking because you get put in jail for drinking so I can take a smoke.’” Smoking was a way to cope with the daily stressors she faced, but she hid this behavior from her family and her work. As with most continuous smokers, she continued to smoke throughout her life, despite strong incentives to not smoke and environmental obstacles. Because she was a teacher, she was not allowed to smoking anywhere on the school property, and she restricted her smoking to her commute or at home. James (man, age 42) also smoked as a way to cope with stress, saying, “I smoke cigarettes because I’m worried about what’s next.” This stress included relationship stress; his smoking was a source of conflict with his wife, who had concerns about how much money cigarettes cost. Surprisingly, this was one of the few references to the high cost of cigarettes within our interviews. James said that his wife would not even discuss smoking, and it was not allowed in the home or car. But he did not want to quit because he said when he got “stressed for a minute, I look for a cigarette” and he did not know what he would do if could not find them. Conflict with his wife made him want to smoke more: “She wants to argue. I grab me a cigarette.” Gail, James, and most of the other continuous smokers linked their (almost) lifelong smoking to their chronic stress.

Smoking as addiction and habit, regardless of social connections.

Several respondents (n=4) said they continued smoking because it was an ingrained habit or an addiction. This subtheme was also seen among two relapsed smokers. While they viewed the reasons for continuing to smoke in adulthood and not being able—or not desiring—to quit as individually-determined (e.g., addiction), their reasons for initiating smoking in the first place were related to social contexts in childhood and early adulthood (e.g., families, workplace). Jared (man, age 31) began smoking at his workplace when he was 23 even though he was repulsed by it as a child: “My dad smoked. I thought it was a filthy habit. I said I will never smoke and then I started.” When he found himself in a work context with others who smoked, he described it as a way to pass the time: “It was not really a peer pressure thing but let’s kill some time. You start and get addicted and it escalates from there.” He also noted that he smoked from “stress level more than anything else,” most notably stress from work, saying he uses the smoke break to “think about things for a while, talk to myself’ and that it serves as “kind of an escape when I want to relax and have ‘me time’.” For this group, smoking persists despite many objections from those within their networks. For instance, Jeffrey (man, age 57) said he continued smoking despite losing friendships over this behavior. He said, “If somebody had a problem with it, it was like, well, see you later…It’s very difficult for me to get over that nicotine addiction.” As with many others who continued smoking and did not quit, Jeffrey saw addiction as the main reason he continued smoking, although this was also within a context of high stress levels.

For continuous smokers, unlike former smokers and relapsed smokers, social connections in adulthood were viewed as less relevant than early life connections, in which smoking patterns were established. But also unlike former and relapsed smokers, and more like never smokers, continuous smokers viewed themselves as largely not impacted by the smoking habits of their social relationships or contexts (including health concerns) in adulthood.

Discussion

Our study results highlight the importance of social connections in shaping smoking trajectories throughout the life course (Elder et al., 2003). Analyzing in-depth interviews allows us to develop a rich description of the connection between social relationships and smoking, revealing key distinctions between the role of social relationships for those at either end of the smoking continuum—never smokers and continuous smokers—and those whose smoking behavior changes during their life course. This rich description offers novel insight into how social connections matter for different types of smokers over the life course. By exploring respondents’ own narratives and explanations regarding their smoking, we identify the key reasons people provide for why they avoid, initiate, quit, fail to quit, and/or continue smoking. We describe how decisions around smoking—or not smoking—are typically viewed in relation to social connections, embedded within broader life course contexts. By using personal narratives to explore these patterns across the entire life course, for all types of smoking behavior, our findings reveal mechanisms through which social connections serve to both encourage and discourage smoking.

For those on either end of the smoking continuum, our findings align with a human development and aging perspective that highlights the importance of early life social connections for later life. Both never smokers and continuous smokers establish their smoking habits early in the life course within the context of early life relationships (e.g., parents, church connections) and carried them forward with age. Notably, we find that adults in both of these trajectories construct narratives that center how social connections early in life motivate their adulthood smoking behaviors. Early life social connections matter for continuous smokers and never smokers who often—but not always—adopt the norms and values of family members and friends as well as religious community ties (Koenig et al., 1998). These social relationships within the institutions of family and religion primarily operate to create a non-smoker status through social support, social contagion (i.e., modeling those healthy behaviors), and social control (i.e., keeping family members away from unhealthy behaviors), in line with past research (Thoits, 2011; Umberson et al., 2008).

The salience of early life social connections on lifelong health habits is particularly important for these never smokers and continuous smokers. Their smoking behaviors are remarkably stable, seemingly unaffected by marriage, employment, or other connections in mid-and later-adulthood. Social connections often facilitate the continuation of smoking for continuous smokers, as people who continue to smoke do so because of workplace or family cultures as well as to cope with relationship stress (Umberson et al., 2008). But continuous smokers also downplay the salience of social connections in mid- and late-adulthood, pointing to the role of addiction as driving the smoking trajectory after the habit had been established. Although they do not mention it directly, this may also reflect that never smokers often come from and remain in more privileged backgrounds as they age, whereas continuous smokers may experience cumulative disadvantage making them more vulnerable to addiction (Graham et al., 2006).

For those who change their smoking behavior, our results highlight the importance of transitions and turning points as related to social connections, distinguishing relapsed and former smokers from those who never or always smoked. Those who quit or relapsed often relate their smoking decisions to transitions and turning points—especially marriage and divorce, friendship changes, employment shifts, and health concerns. Former smokers credit their success in quitting to moving away from relationships that encouraged smoking, and toward relationships or environments that discouraged smoking. This finding aligns with research showing that transitioning into marriage and parenthood is accompanied with broader expectations about behaving responsibly which includes practicing healthy behaviors (Freeh, 2014; Pampel et al., 2014).

Building on these transitions and turning points, as prior research reveals (Christakis & Fowler, 2008), smoking is strongly reflective of social connections that shape smoking habits through multiple processes including contagion and social control. We find that it is the social connections people have during transitions and turning points that are particularly salient in shaping smoking behavior changes. In contrast to those at either end of the smoking continuum, for those who quit smoking or relapse, decisions to quit—or at least attempt to quit—are less clearly motivated by early life social connections but are often viewed by respondents as primarily related to social connections in mid- and later-adulthood. Moreover, our study provides insight into how the impact of social connections is amplified by broader institutional and life course contexts. For example, some workplaces (e.g., theaters, restaurants, bars) have strong smoking cultures (Kelly et al., 2018), and the smoking habits of co-workers within these spaces may be particularly salient.

Not surprisingly, the long-term impact of these turning points depends on stability with the associated social connections. Instability in general is associated with poorer health—in part because it creates stress, and smoking provides a way of coping with that stress (McDermott et al., 2006). Instability is also linked to financial stress, which is a key obstacle for smoking cessation although not a primary theme in our interviews (Broms et al., 2004). The narratives of relapsed smokers tend to be comprised of multiple turning points. Given that turning points constitute major life transitions, they require adoption of new social roles and relationships, representing a major stress and decline in well-being (Wethington, 2005). Addiction is also an impediment to a stable non-smoking status, and undoubtedly plays a key role in distinguishing those who quit successfully from those who relapse (Subramaniyan & Dani, 2015). Financial resources and health care access (e.g., medical counseling) are likely also important, although this is also not discussed in detail by respondents (Graham et al., 2006).

One final contribution of our descriptive analysis is that future work should consider the possibility that initiating, avoiding, or quitting smoking reflect a type of life course transitions or turning points (e.g., quitting smoking as a key life transition), as change in smoking status may lead to changes in opportunities or social connections. Decisions to initiate or continue smoking limit work and housing opportunities and place strain on intimate and family relationships for some respondents (Stuber et al., 2008). And given the social significance of smoking for many respondents, transitions into and out of identities of smoker, non-smoker, and “social smoker” is on par with transitions across other identities (e.g., family status, employment status) in terms of its implications for their social ties, housing, and employment.

Limitations

A qualitative approach to smoking behaviors across the life course offers unique contributions and perspectives, but several limitations should be addressed. We analyzed first-hand narratives of how smoking behaviors shift over time and explanations for these behaviors, but these accounts are subject to retrospective bias (Esterberg, 2002). Additionally, we originally set out to examine how these explanations varied by race and gender, but because of small sample sizes, we did not reach saturation in these across-group analyses. This similarly restricted us from reaching robust conclusions about age, cohort, and socioeconomic differences including race and educational attainments. Past longitudinal survey research demonstrates that race and gender shift in importance over the life course in how they impact smoking (Lawrence, Pampel, & Mollbom, 2014), suggesting that future research should continue to unpack the potential racial/ethnic, gender, and age/cohort differences in explanations for smoking behavior using multiple methods.

As an additional limitation, in our analysis of these interviews, three life course principles are most relevant—linked lives, human development and aging, and turning points and transitions—but this is not to say other life course principles do not matter for smoking. Notably, within smoking decisions, people exercise human agency, meaning they are actively constructing their own life courses within the opportunities and constraints of social circumstances (Elder et al., 2003; Hitlin & Elder, 2007). Similarly, the life course principles of timing of events and historical context also are important for understanding smoking behavior, given the shifting culture and legal context around smoking (Kelly et al., 2018; Stuber et al., 2008), although these are beyond the scope of our study design. Also important are the psychological and physiological nature of nicotine addiction (Subramaniyan & Dani, 2015), genetic dispositions towards smoking (Chen et al., 2016), and the presence or absence of formal interventions to aid in smoking cessation (e.g., medical counseling or information), but these are again outside of this study’s design and generally only discussed by the continuous smokers. Although our study was designed to provide a more general overview of social relationships and health behaviors, future analysis aimed at better gauging the effect of supports and resources around smoking would benefit from adapting the method used by Verd and López (2011),

Conclusion

Building on prior work connecting smoking behavior with a life course perspective and focusing on social connections, our approach affords a more nuanced description of the decisions and transitions related to social connections and smoking behavior, including those who avoid it entirely. By blending the life course perspective with our empirical analysis, we develop a rich description of the mechanisms behind decisions to never smoke, begin smoking, quit smoking, and continue smoking, demonstrating why it is that social connections are so influential for smoking behavior. Examining respondents’ own explanations for smoking goes beyond survey methods of measuring associations between, for example, marital status and smoking. Instead, it allows us to see the salience of social connections during human development and transitions according to respondents’ own narratives. Survey methods also typically divide smoking behavior status into current smokers, former smokers, and never smokers (Lariscy et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2018), treating smoking as a relatively stable activity, but our analysis highlights that this approach misses the experiences of relapsed smokers, whose smoking behavior is more dynamic, and does not allow us to consider when, why, and how these shifts occur. Past studies have demonstrated that early life matters for health and health behaviors (Anderson, Foster, & Frisvold, 2010; Hayward & Gorman, 2004), but our findings suggest that early life is also important for smoking behavior, although perhaps especially for a subset of people—never smokers and continuous smokers. Similarly, past research demonstrates how the smoking behavior of people spread within social networks (Christakis & Fowler, 2008) yet our analysis suggests these are important primarily in combination with other life course transitions and social connections.

Further, comparing the linked lives of never smokers, former smokers, relapsed smokers, and continuous smokers could provide direction and guidance into achieving the Healthy People 2020 goals of further reducing smoking rates (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). The principle of human development and aging suggests that the most critical life course points to reduce smoking should occur in childhood and adolescence. But the failure of past programs—often conducted within schools (Anderson et al., 2010)—may be due to the fact that most early life decisions about smoking or not smoking occur within families. At the same time, both linked lives and transitions/turning points in combination with our results demonstrate that early life smoking interventions are not enough for widespread change in smoking habits. Smoking habits may begin or be rejected in early life for many, but there is important variation in who continues smoking and why—and respondents in our study understand their smoking behavior as partly driven by the smoking norms of and social stress from those around them in mid- and later-life as well. There is a need for future research on the complex interplay between social connections and policy interventions. Our study sets the stage for future research to systematically explore the dynamic role of social interactions and the broader social environment, including the health care system (i.e., patient-provider interactions) and efforts to restrict smoking (i.e., tobacco clean air bans) or enable cessation (i.e., detoxification programs), better guiding the design of interventions and policies. Rather than attempting a one-size-fits-all approach, we need to consider when, how, and why social connections shape trajectories of smoking behavior.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by a National Institute on Aging Grant RO1 AGO26613, Debra Umberson, Principal Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Mieke Beth Thomeer, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Elaine Hernandez, Indiana University.

Debra Umberson, The University of Texas at Austin.

Patricia A. Thomas, Purdue University

Works Cited

- Anderson KH, Foster JE, & Frisvold DE (2010). Investing in health: The long-term impact of head start on smoking. Economic Inquiry, 48(3), 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew M, Eggerling-Boeck J, Sandefur GD, & Smith B (2006). The “inner side” of the transition to adulthood: How young adults see the process of becoming an adult. Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Broms U, Silventoinen K, Lahelma E, Koskenvuo M, & Kaprio J (2004). Smoking cessation by socioeconomic status and marital status: The contribution of smoking behavior and family background. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6(3), 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D (2018). The linked lives principle in life course studies: Classic approaches and contemporary advances In Alwin DF, Felmlee DH, & Kreager DA (Eds.), Social Networks and the Life Course (pp. 41–63). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). Quitting smoking among adults— United States, 2001-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 60(44), 1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Schwartz O, Simmons JG, Whittle S, Byrne ML,… & Lubman DI (2015). Affective behavior and temperament predict the onset of smoking in adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-S, Baker T, Hung RJ, Horton A, Culverhouse R, Hartz S, Saccone N, Cheng I, Deng B, Han Y, Hansen ΗM, Horsman J, Kim C, Rosenberger A, Aben KK, Andrew AS, Chang S-C, Saum K-U, & Bierut LJ (2016). Genetic risk can be decreased: Quitting smoking decreases and delays lung cancer for smokers with high and low CHRNA5 risk genotypes—a meta-analysis. EBioMedicine, 11, 219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Jacques-Tiura AJ (2014). Smoking initiation associated with specific periods in the life course from birth to young adulthood: Data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), ell9–el26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2008). The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(21), 2249–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deterding NM, & Waters MC (2018). Flexible coding of In-depth interviews: A twenty-first-century approach. Sociological Methods & Research, OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr., Johnson ΜK, & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory In Mortimer JT & Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson B (2003). Social networks: The value of variety. Contexts, 2(1), 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Esterberg KG (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. Boston: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Freeh A (2014). Pathways to adulthood and changes in health-promoting behaviors. Advances in Life Course Research, 19, 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H, Inskip ΗM, Francis B, & Harman J (2006). Pathways of disadvantage and smoking careers: Evidence and policy implications. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(suppl 2), ii7–ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SA, & Schaefer DR (2014). With a little help from my friends? Asymmetrical social influence on adolescent smoking initiation and cessation. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(2), 126–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, & Gorman BK (2004). The long arm of childhood: The influence of early-life social conditions on men’s mortality. Demography, 41(1), 87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin S, & Elder GH Jr. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein B (2018). What autobiographical narratives tell us about the life course: Contributions of qualitative sequential analytical methods. Advances in Life Course Research OnlineFirst. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Vuolo M, Frizzell LC, & Hernandez EM (2018). Denormalization, smoke-free air policy, and tobacco use among young adults. Social Science & Medicine, 211, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, Cohen HJ, Hays JC, Larson DB, & Blazer DG (1998). The relationship between religious activities and cigarette smoking in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A, 53(6), M426–M434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreager DA, Haynie DL, & Hopfer S (2013). Dating and substance use in adolescent peer networks: A replication and extension. Addiction, 108(3), 638–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariscy JT, Hummer RA, & Hayward MD (2015). Hispanic older adult mortality in the United States: New estimates and an assessment of factors shaping the Hispanic paradox. Demography, 52(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence EM, Pampel FC, & Mollbom S (2014). Life course transitions and racial and ethnic differences in smoking prevalence. Advances in Life Course Research, 22, 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R, & Wright L (2015). Better off alone than with a smoker: The influence of partner’s smoking behavior in later life. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 71(4), 687–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott LJ, Dobson A, & Owen N (2006). From partying to parenthood: Young women’s perceptions of cigarette smoking across life transitions. Health Education Research, 21(3), 428–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HD, Lui L, Ensrud K, Cummings SR, Cauley JA, & Hillier TA (2018). Associations of smoking, moderate alcohol use, and function: A 20-year cohort study of older women. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 4, 2333721418766127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC, Mollborn S, & Lawrence EM (2014). Life course transitions in early adulthood and SES disparities in tobacco use. Social Science Research, 43, 45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C, Thomeer ΜB, Kissling A, & Liu H (2016). Relationships with parents and adult children’s substance use. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C, Thomeer MB, Lodge AC, Umberson D, & Underhill M (2014). Diet and exercise in parenthood: A social control perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(5), 1047–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy KM (2012). In search of a culture: Navigating the dimensions of qualitative research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 660–665. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, & Link BG (2008). Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniyan M, & Dani JA (2015). Dopaminergic and cholinergic learning mechanisms in nicotine addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1349(1), 46–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavory F, & Timmermans S (2014). Abductive analysis: Theorizing qualitative research. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health .Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, & Reczek C (2007). Interactive stress and coping around parenting: Explaining trajectories of change in intimate relationships over the life course. Advances in Life Course Research, 12, 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Donnelly R, & Pollitt AM (2018). Marriage, social control, and health behavior: A dyadic analysis of same-sex and different-sex couples. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(3), 429–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Liu H, & Reczek C (2008). Stress and health behavior over the life course. Advances in Life Course Research, 13, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Verd JM and López M (2011). The rewards of a qualitative approach to life-course research. The example of the effects of social protection policies on career paths. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3), 15. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E (2005). An overview of the life course perspective: Implications for health and nutrition. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 37(3), 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]