Abstract

Purpose –

The aim of this study was to evaluate semi-automated surgical procedures for lens extraction by using the OCT-integrated Intraocular Robotic Interventional Surgical System (IRISS).

Setting –

A collaboration between the Stein Eye Institute and the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Design –

Semi-automated lens extraction was performed on 30 post-mortem pig eyes using a robotic platform integrated with an optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging system. The lens extraction was performed using a series of automated steps including robot-to-eye alignment, irrigation/aspiration (I/A) handpiece insertion, anatomical modeling, surgical path planning, and I/A handpiece navigation. Intraoperative surgical supervision and human intervention were enabled by providing real-time OCT image feedback to the surgeon via a graphical user interface (GUI).

Methods –

Manual preparation of the pig eye models, including corneal incision and capsulorhexis, was performed by a trained cataract surgeon prior to the semi-automated procedures for lens extraction. A scoring system was used to assess surgical complications in postoperative evaluation.

Results –

The semi-automated lens extraction procedures were performed on 30 post-mortem pig eyes. Complete lens extraction was achieved on 25 of 30 eyes. For the remaining five eyes, small (≤ 1 mm3) pieces of lens were postoperatively detected near the lens equator where the transpupillary OCT was unable to image. No posterior capsule rupture or corneal leakage was reported. The mean surgical duration was 277±42 s. Based on a 3-point scale (with 0 representing no damage), damage to the iris was 0.33±0.20, damage to the cornea was 1.47±0.20 (due to tissue dehydration), and stress at the incision was 0.97±0.11.

Conclusion –

The efficacy of performing semi-automated lens extraction procedures in animal models was evaluated with post-mortem pig eyes. No posterior capsule rupture was reported and complete lens removal was achieved in 25 trials without significant surgical complications. Further refinements to the procedures will be required before fully automated lens extraction can be realized.

Keywords: Robotic surgery, automated intraocular surgery, OCT guidance, cataract surgery, lens extraction, capsular bag detection

Introduction

Worldwide, approximately one-third of cases of blindness and one-sixth of cases of vision impairment are caused by cataracts.1 Innovative technologies developed for cataract surgery have improved specific surgical steps such as laser-assisted corneal incision,2 capsulorhexis,3 and lens fragmentation.4 However, lens extraction—wherein the majority of c omplications occur5— continues to be manually performed and represents the most critical step of cataract surgery. If incomplete, limited vision recovery results; if improperly performed, surgical complications can occur.

Posterior capsule rupture (PCR) occurs when excessive vacuum force is used by the phacoemulsification or I/A handpiece in close proximity to the capsule (1.8–4.4%). 6 Every year, over 70,000 patients in the United States and 352,000 patients worldwide suffer from PCR.6 PCR increases the incidence rates of retinal detachment, macular edema, intraoperative lens dislocation, and endophthalmitis.7,8 Eliminating PCR would decrease the vision-threatening complications of cataract surgery. However, the PC is invisible and delicate, with a thickness of approximately 5–10 µm and an allowable displacement of only hundreds of micrometers.9 With the limited reaction time of a human surgeon (360 ms),10 the PC could rupture before the surgeon is able to react. On the other hand, incomplete lens extraction occurs if the surgeon is too conservative.

Developed systems include teleoperated robotic platforms for assisting in vitreoretinal surgery11,12 but the state of the art in cataract surgery remains limited. To date, no systems for cataract surgery (automated or otherwise) have received FDA approval or been used to perform experiments on human subjects. Unresolved issues include (1) aligning the robot-guided I/A handpiece with the corneal incision, (2) registering anatomical structures for surgical path planning, and (3) accounting for the dynamic nature of the surgical environment to safely navigate within the eye.

In this study, semi-automated lens extraction is evaluated in pig eye models using a robotic system—the Intraocular Robotic Interventional Surgi cal System (IRISS)13,14. The system is guided by optical coherence tomography (OCT) with a minimal degree of human intervention15. The OCT image feedback enables automated procedures such as I/A handpiece alignment, modeling of the anterior segment, generation of an I/A handpiece surgical path, and real-time supervision and intervention.

Materials and methods

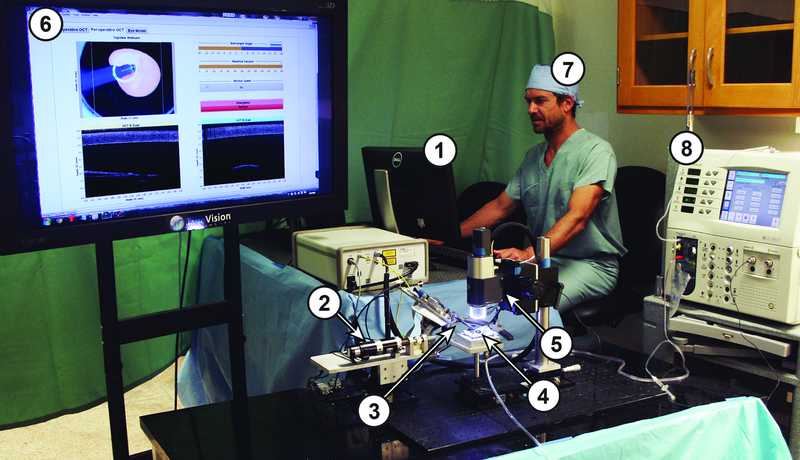

The overall system setup is shown in Figure 1 and the relevant engineering metrics are highlighted in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Shown is the overall system setup; numbers indicate major system components and correspond to the elements illustrated in Figure 2. These elements are (1) the Control Software, (2) the IRISS, (3) the I/A Handpiece, (4) the Pig Eye Model, (5) the OCT with integrated CMOS camera, (6) the Graphical User Interface (GUI), (7) the Surgeon, and (8) the Alcon ACCURUS.

Table 1.

Engineering metrics of the robotic and OCT systems

| The IRISS Robotic System 17,18 | |

|---|---|

| Positional precision* | 27±2 µm |

| Positional accuracy† | 205±3 µm |

| Robot-to-eye alignment time | < 1 min |

| Mounted tool | 8172 UltraFLOW straight-tip irrigation/aspiration handpiece with side aspiration port (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) |

| The OCT System | |

| Detection scheme | Spectral Domain |

| Model | Telesto II 1060LR with objective lens LSM04BB (ThorLabs, Newton, NJ) |

| Central wavelength | 1060 nm |

| Volume scan dimensions | 10×10×9.4 mm |

| Volume scan acquisition time | 33.2 s |

| Axial resolution (in air) | 9.18 µm |

| B-scan acquisition and display rate | 4.65 Hz |

“Positional precision” refers to the ability to repeatably touch the same point

“Positional accuracy” refers to the ability to exactly touch a specified point

Semi-automated lens extraction

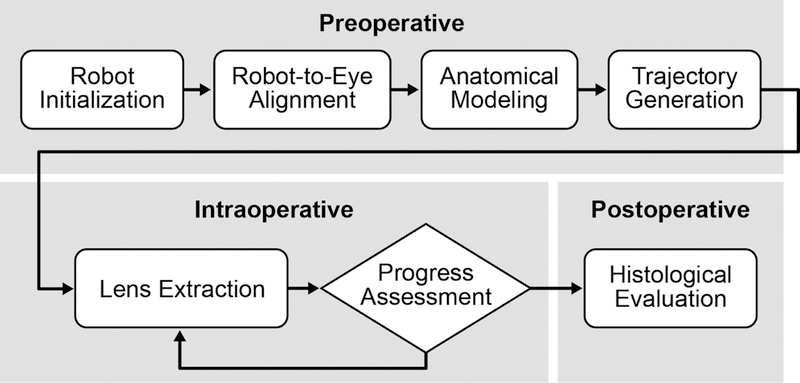

The procedures for semi-automated lens extraction15 can be divided into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative stages (Figure 2). During the preoperative planning stage, the robotic system was automatically initialized and self-calibrated to ensure the precision and accuracy of its motion. The location and orientation of the corneal incision were determined from an OCT volume scan of the incision. These measurements enabled automated robot alignment and insertion of the I/A handpiece, where the robot system autonomously aligned its Remote Center of Motion (RCM) to the corneal incision and inserted the I/A handpiece through it. This automated alignment process required less than one minute.

Figure 2.

Shown are the procedures for semi-automated lens extraction, divided into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative stages.

After the I/A handpiece was aligned to the eye, the system autonomously constructed an anatomical model of the anterior segment from OCT volume scans. Using this model, a workspace was defined for I/A handpiece navigation and surgical safety margins were established (1.5 mm from any part of the iris, 0.1 mm from the corneal endothelium, and 3.5 mm to the posterior capsule (PC)). Irrigation and aspiration forces were delivered to the I/A handpiece through the robotic platform and automatically regulated according to the proximity of the I/A handpiece to the PC. During the autonomous lens-extraction phase, the robotic system autonomously tracked the preoperatively planned lens-extraction trajectory. To accommodate for the variable surgical environment, a GUI allowed the surgeon to monitor and override the automated lens-extraction procedure, including the lens-extraction trajectory, the applied aspiration/irrigation forces, and the predefined workspace and surgical safety margins. In addition, an OCT-based progress assessment was performed by the human surgeon every two minutes during lens extraction. If no visible lens material remained in the capsular bag, the surgery would be concluded and postoperative evaluation performed. If the second trajectory concluded but small (≤ 1 mm3) piece(s) of lens material remained, the robotic system would be directed to the location of the remaining lens material by the surgeon via the GUI. Otherwise, the robotic system would continue tracking the lens-extraction trajectory until the subsequent progress assessment.

Preparation of pig eye model and surgical instruments

The semi-automated lens extraction was validated on post-mortem pig eyes (Sioux-Preme Packing, Sioux City, IA) pinned into a custom polystyrene holder. Manual preparation of each eye was performed by a trained cataract surgeon (AAF) under a surgical microscope (M840, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grover, IL). The surgeon created a uniplanar corneal incision with a 2.8 mm keratome knife, performed circular and continuous capsulorhexis with 5 mm diameter, and performed hydrodissection and hydrodelamination of the lens with balanced salt solution. As the final preparation step, the anterior segment was filled with viscoelastic gel (1% sodium hyaluronate) to prevent collapse of the anterior chamber. Mean harvested pig eye pupil diameter was recorded as 8.50±0.59 mm.

A straight-tip I/A handpiece with side aspiration port (8172 UltraFLOW, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) was installed with an irrigation sleeve and was mounted on the IRISS. The I/A handpiece was connected to a modified ACCURUS Surgical System, Model 800CS (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX), to provide robot-controlled irrigation and aspiration for lens extraction and intraocular pressure regulation with a maximum vacuum force of 600 mmHg.

Evaluation of the procedure

A postoperative histologic examination was performed by the cataract surgeon using the surgical microscope. The evaluation metrics were:

Posterior capsule rupture (Yes/No)

Lens extraction (Complete/Near-Complete/Incomplete)

Iris damage (Damage Level 0–3)

Cornea damage (Damage Level 0–3)

Incision stress (Stress Level 0–3)

For assessing lens extraction, the surgeon examined the entire capsular bag (including the equator) to search for remaining lens material. If none was found, the procedure was considered “complete.” If particles were found, they were asse ssed for size. If all found particles were < 1 mm3, the procedure was considered “near-complete.” If any particle was ≥ 1 mm3, the procedure was considered “incomplete.” Damage and stress leve ls were qualitatively defined according to Table 2. Finally, the surgical duration of aspiration (the amount of time the I/A handpiece was in the eye) was recorded for each trial.

Table 2.

Definition of postoperative evaluation scores

| Description | Score |

|---|---|

| Iris Damage | |

| No iris contact | 0 |

| Iris contact without damage | 1 |

| Iris contact and damage in a single location | 2 |

| Iris contact and damage in multiple locations | 3 |

| Cornea Damage | |

| No evidence of endothelial or stromal defect | 0 |

| Mild descemet folds, no stromal defect | 1 |

| Descemet fold and mild corneal edema | 2 |

| Opaque cornea | 3 |

| Incision Stress | |

| Preserved incision | 0 |

| Mild opening of the incision, does not compromise sealing | 1 |

| Opening of the incision, compromised sealing | 2 |

| Widening of the incision with compromised sealing | 3 |

Results

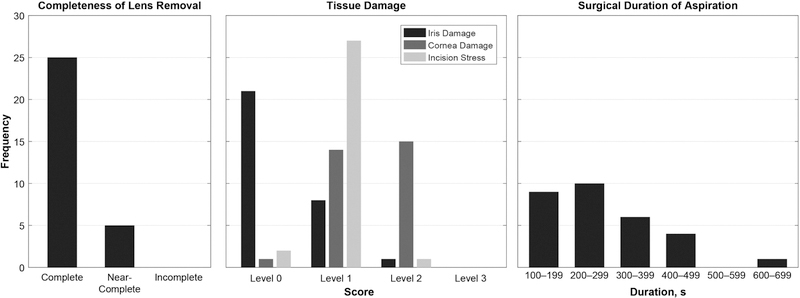

The semi-automated lens extraction was performed on n = 30 post-mortem pig eyes. The results of the postoperative histologic examination are shown in Figure 3. No posterior capsule rupture was encountered in any of the 30 trials. Lens extraction was assessed as “complete” in 25 trials, “near-complete” in five trials, and “incomplete” in zero trials. In the five trials with near-complete lens extraction, the small (≤ 1 mm3) lens particles were found adhered to the lens equator. The mean surgical duration was 277±42 s. In all trials, preparation of the eye by the surgeon required approximately five minutes; automated alignment of the robotic system to the eye required less than one minute. The iris damage level was 0.33±0.20, the cornea damage level was 1.47±0.20, and the incision stress level was 0.97±0.11.

Figure 3.

Shown are the summarized results of the semi-automated lens extraction trials including the completeness of lens removal, tissue damage, and surgical duration.

Discussion

This work represents the first success in performing semi-automated lens extraction guided by a transpupillary OCT imaging system for cataract surgery. The semi-automated procedures which address challenges of OCT-guided surgical automation are proven safe and effective for: (1) the lignment of the robot-guided I/A handpiece to the corneal incision; (2) the reconstruction of intraocular anatomical structures for surgical path planning; and (3) the ability to accommodate the dynamic nature of the surgical environment to ensure surgical safety and outcomes.

The automated image segmentation and modeling algorithm was able to reconstruct the anatomical model from OCT scans of the anterior segment. Without requiring the manual labeling of tissue, the algorithm establishes the anatomical model and generates the I/A handpiece trajectory for lens extraction. The accuracy of PC modeling was 79.6±23.3 µm, which was approximately 40 times smaller than the surgical safety margin between the I/A handpiece trajectory and the PC (3.5 mm).

The OCT imaging system allows for real-time surgical supervision and intervention. The user interface was designed for modification of the programmed lens-extraction trajectory such that the dynamic surgical environment could be accommodated if required. The surgeon was not required to handle the I/A handpiece or manual controls during the operation. If necessary, the robot could be commanded by clicking on the displayed images acquired from the OCT and its integrated camera. This feature eliminated reliance on the surgeon’s dexterity and familiarity with the robotic system. This development represents an important milestone toward fully-automated lens extraction, especially because real-time OCT image segmentation remains a challenging task.

Among the 30 trials, the iris was brushed by the self-navigated I/A handpiece in nine trials primarily due to the limited dilation of the porcine eye model as well as sub-millimeter shifting of the eye. These complications could be mitigated through improved dilation, implementing eye tracking, or increasing the surgical safety margin around the iris. Damage to the cornea was expected due to accumulated tissue dehydration and natural degradation of the pig eyes which were shipped overnight from the slaughterhouse. The cornea damage was proportional to the surgical duration (the average surgical duration of the trials with cornea damage level of 1 was 220.6 s; 333.5 s for the trials with cornea damage level of 2) due to air exposure and the initiation of dehydration. Aside from the corneal incision, the I/A handpiece never touched the corneal endothelium during the trials and therefore contact with the I/A handpiece was not a source of damage. Lastly, the incision stress was minimal (level 1 in almost every trial) due to the automated alignment and adherence of the I/A handpiece motion about the robotic RCM.

Among the 30 trials, no PCR was diagnosed and complete lens extraction was achieved in 25 of 30 trials. In the five trials where only near-complete lens extraction was achieved, only small (≤ 1 mm3) pieces of lens material were postoperatively discovered near the lens equator. Nevertheless, we consider these trials successful because the equatorial area hidden by the iris remained invisible during the entire procedure and represents a deficiency of the sensing modality— not the developed automated procedures. This deficiency necessitates an improved or augmented means to visualize the lens equator to enable complete lens extraction.

To implement the developed semi-automated procedures in future preclinical trials, several refinements are currently underway. First, inclusion of an additional imaging modality that can visualize the lens equator and detect lens material posterior to the iris will improve the completion of lens extraction. Second, regulation of the intraocular pressure via active irrigation control will stabilize the intraocular tissues and reduce the risk of surgical complications. Third, the application of artificial intelligence can prove benefit towards resolving the challenging problem of real-time image segmentation of OCT data and allow for development of a real-time, OCT-based, tissue-tracking algorithm that can be used to update the anatomical model and adjust the navigation strategy. Finally, we will continue to pursue fully-automated lens extraction and cataract surgery by combining a femtosecond laser system with the IRISS.

Synopsis.

Semi-automated lens extraction procedures were evaluated using the Intraocular Interventional Surgical System (IRISS) on 30 post-mortem pig eyes. No posterior capsule rupture was reported and complete lens removal was achieved in 25 trials without significant surgical complications.

Summary.

What was known:

The most critical step of cataract surgery—lens extraction—remains a manual operation to remove the lens nucleus and cortical material from the capsular bag. Surgical complications such as PCR and incomplete lens extraction occur during this stage.

Transpupillary OCT images have been used in preoperative diagnosis and surgical planning. However, no existing system applies transpupillary OCT data to intraoperative lens extraction.

What this paper adds:

The first semi-automated lens extraction on post-mortem pig eyes is demonstrated with use of a robotic system integrated with an OCT imaging system.

Automated steps that are demonstrated include alignment of the I/A handpiece to the corneal incision, anatomical modeling, trajectory generation, and I/A handpiece insertion. Lens extraction was “partially” automated in the sense that surgeon intervention was permitted during the otherwise fully autonomous lens-extraction operation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Harrison Cheng and Warren S. Grundfest for their consultation on the OCT technical specifications and software interfacing and Yan-Chao Yang and Stefano Soatto for their consultation on the capabilities and limitations of computer vision and perception.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Institutes of Health under Grant No. 5R21EY024065-02; The Hess Foundation, New York, NY, USA; The Earl and Doris Peterson Fund, Los Angeles, CA, USA; and the Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), New York, NY, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2012. May 1; 96(5):614–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson KE, Braga-Mele R, Cabot F, Davidson R, Dhaliwal DK, Hamilton R et al. Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2013. November 1; 39(11):1753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palanker D, Schuele G, Friedman N, Andersen D, Culbertson W. Cataract surgery with OCT-guided femtosecond laser. In Bio-Optics: Design and Application 2011 Apr 4 (p. BTuC4). Optical Society of America

- 4.Roberts TV, Lawless M, Bali SJ, Hodge C, Sutton G. Surgical outcomes and safety of femtosecond laser cataract surgery: a prospective study of 1500 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology 2013. February 1; 120(2):227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimbel HV. Posterior capsule tears using phaco-emulsification causes, prevention and management. European Journal of Implant and Refractive Surgery 1990. March; 2(1):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai P, Minassian DC, Reidy A. National cataract surgery survey 1997–8: a report of the results of the clinical outcomes. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1999. December 1; 83(12):1336–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell M, Gaskin B, Russell D, Polkinghorne PJ. Pseudophakic retinal detachment after phacoemulsification cataract surgery: Ten-year retrospective review. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 2006. March 1; 32(3):442–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ti SE, Yang YN, Lang SS, Chee SP. A 5-year audit of cataract surgery outcomes after posterior capsule rupture and risk factors affecting visual acuity. American journal of ophthalmology 2014. January 1; 157(1):180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krag S, Andreassen TT. Mechanical properties of the human posterior lens capsule. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2003. February 1; 44(2):691–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng B, Janmohamed Z, MacKenzie CL. Reaction times and the decision-making process in endoscopic surgery. Surgical Endoscopy & Other Interventional Techniques 2003. June 19; 17(9):1475–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheon GW, Gonenc B, Taylor RH, Gehlbach PL, Kang JU. Motorized Microforceps with Active Motion Guidance Based on Common-Path SSOCT for Epiretinal Membranectomy. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2017. December; 22(6):2440–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu H, Shen JH, Joos KM, Simaan N. Calibration and Integration of B-Mode Optical Coherence Tomography for Assistive Control in Robotic Microsurgery. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2016. December; 21(6):2613–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahimy E, Wilson J, Tsao TC, Schwartz S, Hubschman JP. Robot-assisted intraocular surgery: development of the IRISS and feasibility studies in an animal model. Eye 2013. August; 27(8):972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JT, Gerber MJ, Prince SW, Chen CW, Schwartz SD, Hubschman JP et al. Intraocular robotic interventional surgical system (IRISS): Mechanical design, evaluation, and master– slave manipulation. The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery 2018. February; 14(1):e1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CW, Lee YH, Gerber MJ, Cheng G, Yang YC, Govetto A et al. Intraocular robotic interventional surgical system (IRISS): semi-automated OCT-guided cataract removal. The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery, 2018; p. e1949. [DOI] [PubMed]