Abstract

The mismatch negativity is a cortical response to auditory changes and its reduction is a consistent finding in schizophrenia. Recent evidence revealed that the human brain detects auditory changes already at subcortical stages of the auditory pathway. This finding, however, raises the question where in the auditory hierarchy the schizophrenic deficit first evolves and whether the well-known cortical deficit may be a consequence of dysfunction at lower hierarchical levels. Finally, it should be resolved whether mismatch profiles differ between schizophrenia and affective disorders which exhibit auditory processing deficits as well. We used functional magnetic resonance imaging to assess auditory mismatch processing in 29 patients with schizophrenia, 27 patients with major depression, and 31 healthy control subjects. Analysis included whole-brain activation, region of interest, path and connectivity analysis. In schizophrenia, mismatch deficits emerged at all stages of the auditory pathway including the inferior colliculus, thalamus, auditory, and prefrontal cortex. In depression, deficits were observed in the prefrontal cortex only. Path analysis revealed that activation deficits propagated from subcortical to cortical nodes in a feed-forward mechanism. Finally, both patient groups exhibited reduced connectivity along this processing stream. Auditory mismatch impairments in schizophrenia already manifest at the subcortical level. Moreover, subcortical deficits contribute to the well-known cortical deficits and show specificity for schizophrenia. In contrast, depression is associated with cortical dysfunction only. Hence, schizophrenia and major depression exhibit different neural profiles of sensory processing deficits. Our findings add to a converging body of evidence for brainstem and thalamic dysfunction as a hallmark of schizophrenia.

Keywords: schizophrenia, major, depressive disorder, mismatch negativity, auditory processing

Introduction

For more than 100 years, Kraepelin’s dichotomy of psychotic and affective disorders has been highly influential on psychiatric nosology, remaining an essential characteristic of current diagnostic classification systems. Its biological foundation, however, has recently been questioned.1 Neurobiological research has consistently documented sensory processing deficits in schizophrenia and—more recently—also in major depression.2,3 In both disorders, sensory deficits are supposed to contribute to symptomatology and represent potential biomarkers.

Within the auditory modality, one of the best-replicated findings in schizophrenia is the reduction of the mismatch negativity (MMN).4 In electroencephalography (EEG), the MMN is an event-related potential component elicited by deviants embedded within a sequence of repetitive auditory stimuli. It is considered a pre-attentive error signal originating in the auditory cortex. Additional contributions of the prefrontal cortex are considered to enable a subsequent shift of attention.5 The reduction of the MMN is discussed as a potential biomarker of schizophrenia,6 although the specificity of this finding is still under debate. Indeed, different studies suggested auditory processing and MMN deficits in both bipolar disorder7,8 and unipolar depression, too.9–11 However, MMN reductions in unipolar depression are challenged by other studies reporting normal or even increased MMN amplitudes.12,13

Recent evidence revealed that auditory change detection is a pervasive property along the hierarchy of the auditory pathway involving also subcortical processing nodes such as the inferior colliculus and thalamus.14,15 This finding, however, raises the question where in the auditory hierarchy the mismatch deficit in schizophrenia first manifests and whether the well-known cortical deficit may even be a direct consequence of dysfunction at lower hierarchical (ie, subcortical) levels.16 Moreover, both disorders are associated with disturbances of functional connectivity which may further contribute to deficits of auditory change detection.17,18 Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been demonstrated to precisely localize the generators of the cortical as well as—more recently—also of the subcortical mismatch responses in healthy human subjects.15,19 By exploiting the high-spatial resolution of fMRI and applying a multifeature mismatch paradigm, we aimed at characterizing disorder-specific profiles for subcortical and cortical mismatch responses in patients with schizophrenia and major depression. Thereby, shared and distinct neurobiological features of these major mental disorders should be disclosed, providing a basis for the development of disease-specific biomarkers.

The previous research led us to the following hypotheses: First, patients with schizophrenia exhibit stronger mismatch deficits than patients with depression in general and second, these mismatch deficits in schizophrenia manifest already at the subcortical level. Third, mismatch profiles differ between diagnostic groups depending on the auditory processing level as well as the investigated deviant type, ie, the mismatch deficits in schizophrenia and depression may be specific to a certain anatomical structure and deviant type. Fourth, across groups, activation deficits at lower processing levels predict deficits in higher levels in a feed-forward manner.16 Fifth, compared to healthy control participants, both patient groups exhibit less synchronized brain activity, ie, reduced functional connectivity within the auditory pathway.”

Methods

Participants

We investigated 29 patients with schizophrenia, 27 patients with unipolar major depressive disorder, and 31 healthy controls matching the patient groups concerning age, gender, and education (see table 1). The patients were recruited through the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psychosomatics of the University Hospital Aachen and an academically associated psychiatric clinic (Katharina Kasper, Gangelt, Germany). The diagnoses of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder were confirmed according to International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria. One patient with an ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia did not fulfill the DSM-IV time criterion of 6 months for schizophrenia and was therefore diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder. None of the patients with schizophrenia fulfilled the criteria of a depressive episode and none of the depressive patients exhibited psychotic symptoms when participating in the study. Patients with other major psychiatric or neurological diagnoses were excluded. The experimental protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the RWTH Aachen University Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, following a complete description of the study.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients With Schizophrenia, Major Depression and Healthy Control Subjects

| Schizophrenia (N = 29) | Major Depression (N = 27) | Healthy Controls (N = 31) | Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F(df = 2) | P |

| Age (years) | 35.3 | 9.5 | 37.4 | 10.4 | 36.4 | 10.0 | 0.31 | .73 |

| Education (years)a | 14.9 | 2.7 | 14.4 | 3.0 | 15.7 | 2.8 | 1.74 | .18 |

| Parental education (years) | 0.61 | .54 | ||||||

| Musical education (years) | 1.8 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 0.37 | .69 | ||

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scoreb | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 4.13 | .02 |

| Digit span test score | 15.5 | 3.8 | 16.4 | 3.3 | 16.1 | 3.4 | 0.43 | .65 |

| Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenz-Test scorec | 29.6 | 4.5 | 29.7 | 3.4 | 29.4 | 6.8 | 0.04 | .97 |

| Regensburger Wortflüssigkeits-Test-K scored | 12.8 | 5.1 | 14.7 | 3.8 | 13.0 | 3.7 | 1.69 | .19 |

| Regensburger Wortflüssigkeits-Test-G-R scored | 11.8 | 4.8 | 14.5 | 3.6 | 13.1 | 3.9 | 2.99 | .06 |

| Trail-making task B (s) | 54.7 | 28.0 | 49.7 | 28.6 | 45.9 | 18.0 | 0.93 | .40 |

| t(df = 54) | P | |||||||

| Medication (percentage of defined daily dose) | ||||||||

| Antipsychotics | 154.0 | 79.6 | 11.1 | 22.1 | 9.01 | .00 | ||

| Antidepressants | 40.2 | 72.6 | 165.1 | 86.1 | −5.88 | .0 | ||

| Mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants | 2.5 | 13.6 | 12.7 | 39.2 | −1.31 | .20 | ||

| Benzodiazepines/hypnotics | 2.8 | 14.9 | 6.7 | 34.6 | −0.56 | .58 | ||

| Global assessment of functioning score | 53.3 | 10.7 | 47.3 | 13.1 | 1.9 | .06 | ||

| Positive and Negative Symptom Scale scores | ||||||||

| Positive symptoms | 10.6 | 3.6 | ||||||

| Negative symptoms | 11.5 | 4.0 | ||||||

| General psychopathology | 21.9 | 4.9 | ||||||

| Depression score | 1.9 | 0.9 | ||||||

| Total | 43.7 | 11.2 | ||||||

| Beck depression inventory-II | 23.9 | 9.8 | ||||||

| Hamilton depression scale | 14.3 | 8.4 | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 (df = 2) | P | |

| Gender | 1.60 | .45 | ||||||

| Male | 19 | 65.5 | 19 | 70.4 | 17 | 54.8 | ||

| Female | 10 | 34.5 | 8 | 29.6 | 14 | 45.2 | ||

| Handedness | 2.38 | .20 | ||||||

| Right | 28 | 100.0 | 25 | 95.8 | 31 | 100 | ||

| Left | 1 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

Note: aIncluding formal 3-year job apprenticeship with compulsory 1 day/week school attendance and university education.

bThe Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence is a screening instrument for nicotine dependence.

cThe Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenztest is a German multiple choice vocabulary intelligence test estimating subjects’ verbal crystallized intelligence.

dThe Regensburger Wortflüssigkeits-Test is a German verbal fluency test.

Experimental Design

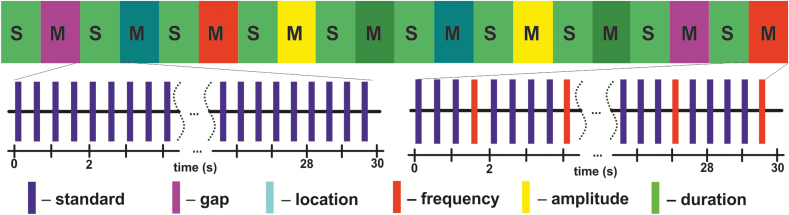

In a block design, repetitive presentation of a standard stimulus (tone with complex partials, 100 ms duration, stimulus onset asynchrony = 500 ms) served as baseline (30 s duration). During mismatch blocks (30 s duration), 1 of 5 different deviant types was presented with a probability of 20%. Deviant types differed from the standard stimuli in duration, location, frequency, amplitude, or an introduced gap (see figure 1 and the more detailed description in the supplementary methods S1 and S2).

Fig 1.

Schematic illustration of the auditory mismatch paradigm. In a block design (10 min), presentation of standard stimuli (tone with complex partials, 100 ms duration, stimulus onset asynchrony = 500 ms) served as baseline (S; 30 s duration each block). During mismatch blocks (M; 30 s), 1 of 5 different deviant types was presented with a probability of 20%. Deviant types differed from the standard stimuli either in duration, location, frequency, amplitude, or an introduced gap.

Whole-Brain Activation Maps

MRI acquisition parameters and preprocessing steps are listed in the supplementary methods S3 and S4. fMRI data analysis was performed using BrainVoyager QX 3.0 (Brain Innovation), Matlab 2014b (MathWorks), and SPSS software, version 23.0 (IBM Corp).

First-level analysis: After preprocessing, individual fMRI data were subjected to an analysis based on a general linear model. The 5 different mismatch conditions served as the predictors of interest; the standard condition served as baseline. Motion parameters were included as predictors of no interest in the regression model. We generated 5 different contrast images for each subject assessing the activation related to each individual mismatch condition in comparison to the standard condition.

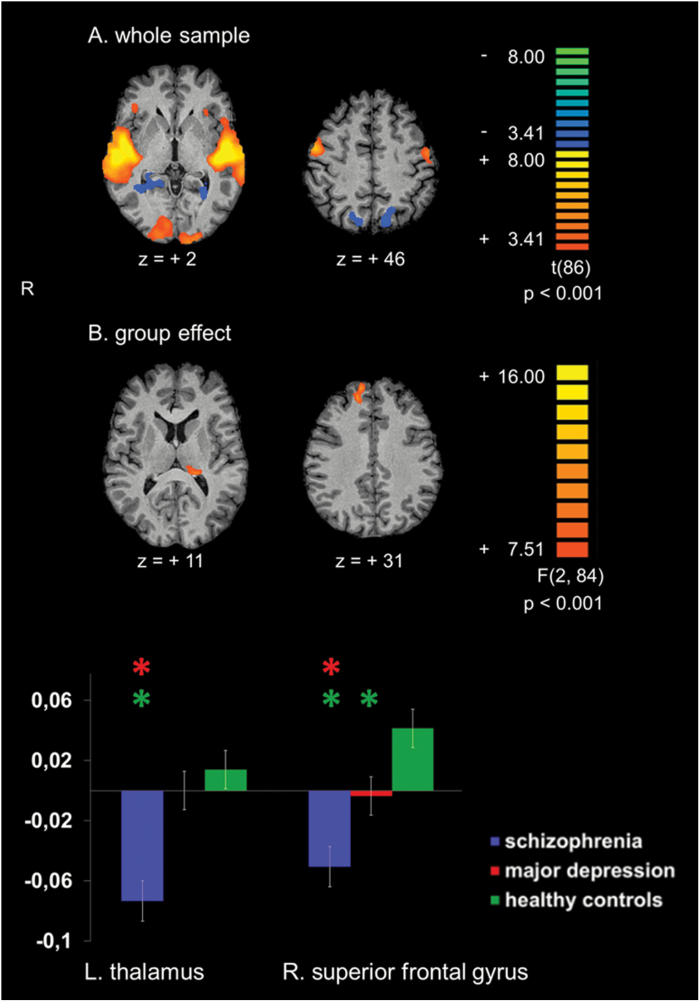

Second-level analysis: The contrast images from the individual first-level analyses entered a second-level random effects analysis. The second-level design matrix included 3 groups, ie, patients with schizophrenia, patients with depression, and healthy controls. Different contrast maps were created: On the one hand, paired t tests compared all mismatch blocks with the standard (baseline) blocks (figure 2A) assessing the overall mismatch activity within the whole sample. On the other hand, F tests assessed the influence of the group membership on the mismatch-related brain activation (figure 2B). Contrast maps with a voxel-wise threshold of P < .001 were corrected for multiple comparisons using a cluster-level correction set to P < .05, which was estimated by a Monte Carlo simulation based on 10 000 iterations.

Fig 2.

Whole-brain activation maps. (A) Activation clusters of the entire sample (29 patients with schizophrenia, 27 patients with major depressive disorder, and 31 healthy control subjects) for the contrast mismatch > standard (baseline) condition. (B) Group differences for the contrast mismatch > standard (baseline) condition. The lower part depicts averaged beta estimates extracted from clusters exhibiting significant group differences. Asterisks above a bar refer to significant group differences. Z-coordinates refer to the Talairach system. L = left. R = right.

Region of Interest Analyses

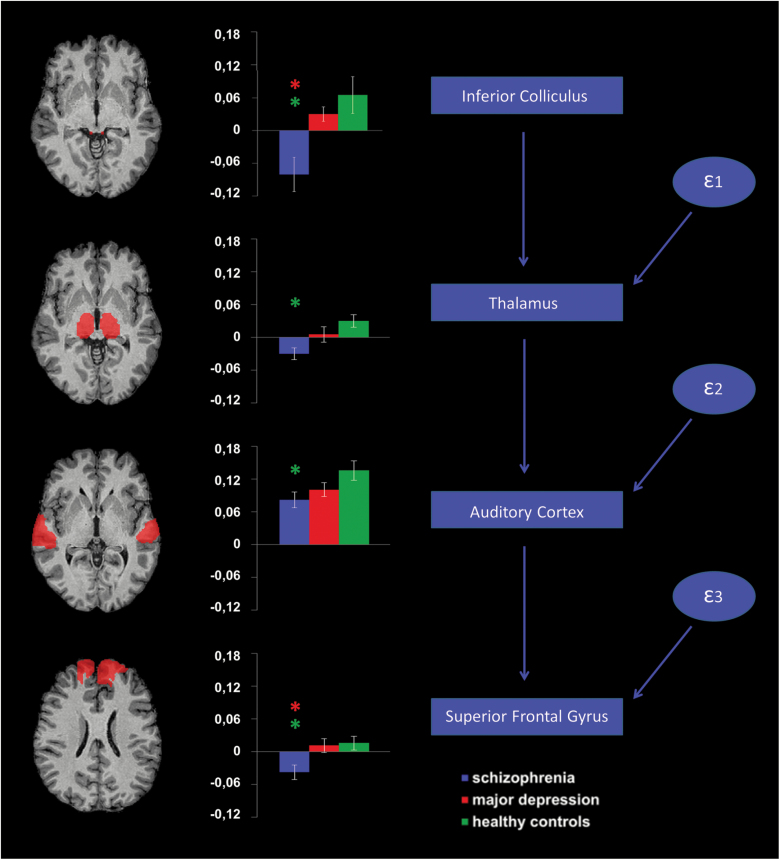

To systematically characterize group-dependent processing differences along the auditory hierarchy, we applied anatomically predefined regions of interest (ROIs) of the bilateral inferior colliculus, thalamus, auditory cortex (Heschl’s and superior temporal gyrus) and superior frontal gyrus (SFG) to assess (1) ROI activation levels, (2) their causal relationship, and (3) ROI-to-ROI connectivity. The SFG was chosen as a prefrontal mismatch generator region because it exhibited significant group differences in the whole-brain activation maps and had been shown to be involved in mismatch processing in previous studies.6,20 Anatomical masks were defined according to the automated anatomical labeling atlas21 except for the inferior colliculi which are not included in this atlas. Therefore, their respective masks were defined as 4 mm (diameter) spheres centered on previously published foci: [x, y, z (mm in Talairach space)] = [± 6, −34, −3].22

ROI Activation Analysis

To assess group-dependent differences of ROI activation levels along the auditory pathway, averaged beta estimates were extracted from each ROI and subjected to a 4-factorial mixed ANOVA with region, side, and deviant type as within-subjects factors as well as the between-subjects factor group.

Path Analysis

To explore a causal relationship between subcortical and cortical activation deficits, the regional beta estimates further entered a path analysis using structural equation modeling (SEM) in SPSS, Amos 25 (IBM Corp). To simplify the model and reduce the number of variables, beta estimates were averaged over both sides for each processing level. We hypothesized that subcortical mismatch deficits in patients with schizophrenia would contribute to deficits at the cortical level,16 and, therefore, we constructed a path model which postulated a bottom-up information flow along the auditory hierarchy23,24 starting in the inferior colliculus and ending in the SFG (see figure 3). To explore the relevance of top-down projections from the auditory cortex to the thalamus and the inferior colliculus,25 we further tested 5 alternative path models integrating different degrees of top-down effects (see supplementary figure S2). The respective model fits were assessed using the χ2 test and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). In line with our hypothesis, the direct bottom-up model yielded the best fit indices. Therefore, we kept this model for further analyses. To assess group differences, within a multigroup SEM analysis, we applied an unconstrained model and several constrained models which assumed the path coefficients to be equal across groups. Applying a nested model comparison assuming the unconstrained model to be correct, the constrained models were evaluated using χ2-difference tests.

Fig 3.

Region of interest activation and path analysis. Anatomical masks (left column) were applied to extract averaged beta estimates for each group (middle column). Asterisks above a bar refer to significant group differences. The proposed structural equation model is depicted in the right column. ε1–ε3 refer to error terms included in the model.

Connectivity Analysis

The averaged time series of each region were subjected to a psychophysiological interaction analysis,26 investigating connectivity as well as its modulation by the experimental condition between each pair of anatomically connected processing nodes, ie, between the inferior colliculus and ipsilateral thalamus, between the thalamus and ipsilateral auditory cortex as well as between the auditory cortex and the SFG at each side. The respective connectivity measures entered a 3-factorial mixed ANOVA investigating processing level and side as within-subjects factors as well as the between-subjects factor group (see also supplementary methods S5).

In each analysis, Gabriel’s test served as post hoc test to explore significant group effects, whereas simple effects analysis was applied to further study significant interactions. Reported P-values are Bonferroni-corrected.

Results

Whole-Brain Activation Maps

Across the entire sample, activations to mismatch blocks emerged bilaterally in the auditory cortex comprising Heschl’s and superior temporal gyrus, the prefrontal cortex (inferior frontal gyrus), precentral gyrus, cuneus, lingual gyrus, as well as the inferior occipital gyrus. Furthermore, deactivation was observed in bilateral precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, parahippocampal gyrus as well as the middle and superior occipital gyrus (see figure 2A. For detailed statistics and a discussion of these findings see supplementary table S1 and supplementary discussion S1).

Significant group differences were identified in the left thalamus (Fpeak (2,84) = 11.15; at [−19, −32, 9] mm in Talairach space) and in the right SFG (Fpeak (2,84) = 11.76; at [14, 43, 30]). Post hoc tests revealed that the group difference in the left thalamus was driven by a significant hypoactivation in schizophrenia compared to healthy controls and depression (for detailed statistics see table 2). In this cluster, no significant group difference was observed between depressed patients and healthy controls. In the right SFG, both patient groups exhibited significantly reduced activation compared to healthy controls, but activity reduction in schizophrenia was more pronounced leading to a significant difference compared to depression as well. In both clusters, either patient group exhibited deactivation compared to baseline whereas healthy controls yielded activation.

Table 2.

Exploring Group Differences in Clusters Exhibiting Significant Group Effects in the Whole-Brain Activation Maps (Left Thalamus, Right Superior Frontal Gyrus) as well as in Anatomically Predefined Regions of Interest of the Bilateral Inferior Colliculus, Thalamus, Auditory Cortex, and Superior Frontal Gyrus.

| Region | Contrast | Mean Difference | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-brain activation maps | ||||

| L thalamus | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.087 | 0.018 | .001 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.073 | 0.019 | .001 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.014 | 0.018 | .83 | |

| R superior frontal gyrus | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.092 | 0.017 | .001 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.047 | 0.017 | .024 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.045 | 0.017 | .029 | |

| Region of interest analysis | ||||

| Inferior colliculus | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.146 | 0.042 | .003 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.111 | 0.044 | .040 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.035 | 0.043 | 1.000 | |

| Thalamus | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.060 | 0.017 | .002 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.035 | 0.018 | .144 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.025 | 0.017 | .465 | |

| Auditory cortex | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.054 | 0.022 | .043 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.019 | 0.022 | 1.000 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.035 | 0.022 | .338 | |

| Superior frontal gyrus | Healthy controls > schizophrenia | 0.053 | 0.018 | .012 |

| Depression > schizophrenia | 0.049 | 0.019 | .031 | |

| Healthy controls > depression | 0.005 | 0.018 | 1.000 |

Note: L = left, R = right. Anatomical labels were obtained using the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas 21. Labels for areas belonging to the same gyrus were concatenated under the label of the respective gyrus. As the inferior colliculi are not included in the AAL atlas, the respective masks were defined as 4 mm (diameter) spheres centered on previously published foci: [x, y, z (mm in Talairach space)] = [± 6, −34, −3] 22.

For the whole-brain activation maps, Gabriel’s test served as a post hoc test to assess group differences indicated by significant F tests. In the region of interest analysis, simple effects analysis was conducted in order to explore group differences in each region after observing a significant interaction of group and region. The respective P-values are Bonferroni-corrected.

Region of Interest Analyses

ROI Activation Analysis

ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the factors group (F(2,84) = 8.72; P < .001) and region (F(1.7, 146.3) = 34.18; P < .001), a significant interaction of the factors region and deviant type (F(6.9, 576.7) = 5.21; P < .001), deviant type and group (F(8,336) = 2.10; P < .036) as well as—most importantly—region and group (F(3.5, 146.3) = 2.66; P < .043). Thus, the results confirmed a significant impact of the processing level within the auditory pathway (ie, cortical vs subcortical) on the observed group differences. The general group effect was driven by significant activation deficits in patients with schizophrenia compared to both healthy controls (mean difference = 0.078; SE = 0.019; P < .001) and patients with depression (mean difference = 0.053; SE = 0.020; P = .025). No significant group difference was observed between patients with depression and healthy controls (mean difference = 0.025; SE = 0.019; P = .490).

In each processing node, patients with schizophrenia demonstrated a significantly reduced activation compared to healthy controls. In the inferior colliculus and SFG, hypoactivation in schizophrenia was also significant compared to depression. In the thalamus, the difference between schizophrenia and depression exhibited only a trend toward significance, whereas in the auditory cortex, there was no significant difference between both patient groups. Differences between depression and healthy controls did not reach statistical significance in any of these regions (see table 2 and figure 3). In contrast to the whole-brain analysis, the SFG did not exhibit significant differences between patients with depression and healthy controls in the ROI analysis. Indeed, the masks applied for the ROI analysis comprised the entire anatomical definition of the SFG diluting the effect of the relatively small hypoactive cluster which was identified in the right SFG in patients with depression in the whole-brain analysis.

Post hoc tests demonstrated that the overall group difference was only significant for duration deviants (see also supplementary figure S1). This difference was explained by a significantly reduced activation in schizophrenia compared to both healthy controls (mean difference = 0.196; SE = 0.042; P < .001 and depression (mean difference = 0.114; SE = 0.043; P < .031). The difference between depression and healthy controls was not significant (mean difference = 0.083; SE = 0.043; P = .166). We did not detect any significant correlation between the respective activation levels and medication or nicotine doses (all P-values above .05)

Path Analysis

Our original structural equation model which postulated a pure bottom-up information flow exhibited the best model fit. The respective fit indices of the unconstrained model suggested a good matching: χ2(9) = 9.08 (P = .430); RMSEA = 0.011 (for the fit indices of the alternative models see supplementary figure S2). None of the nested model comparisons was able to infer group differences (see supplementary table S2). Consequently, the proposed causal relationship between activations along the auditory pathway has to be considered to be valid for each group, ie, participants who exhibit less activation in a respective region tend to have less activation in the next region in the hierarchy. Accordingly, subcortical deficits observed in schizophrenia tend to propagate along the auditory pathway and contribute to cortical deficits.

Connectivity Analysis

ANOVA revealed a significant group effect on connectivity (F(2, 84) = 7.04, P = .001), whereas no significant group effect was observed on condition-dependent connectivity (F(2, 84) = 0.13; P = .876). Post hoc tests revealed that both patient groups exhibited reduced connectivity compared to healthy controls (schizophrenia: mean difference = 0.066; SE = 0.027; P = .049; major depression: mean difference = 0.101; SE = 0.027; P = .001), whereas the patient groups did not significantly differ between each other (mean difference = 0.035; SE = 0.028; P = .513). Furthermore, significant effects on connectivity emerged for the factors Level (F(2, 168) = 49.86; P < .001), Side (F(1, 84) = 19.48, P < .001), and the interaction between both factors (F(1.6, 138.5) = 7.64, P = .002). Significant effects on condition dependent connectivity were only observed for the interaction of the factors Level and Side (F(2, 168) = 3.92; P = .022). No other factor yielded significance.

Discussion

This study investigated the hemodynamic analogue of auditory mismatch processing in patients with schizophrenia, depression, and healthy participants. At the cortical level, the MMN is generated by a temporofrontal network comprising the auditory cortex and an additional generator located in the prefrontal cortex which is considered to initiate an involuntary switch of attention.5 In agreement with the literature, patients with schizophrenia demonstrated mismatch deficits both in the auditory and prefrontal cortex which have been attributed to pathophysiological key features such as structural deficits of the superior temporal lobe, reduced temporoprefrontal connectivity, and local dysfunction of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor system.2,27

In depression, mismatch deficits were only detected in a small cluster within the right SFG. In a similar vein, some of the previous MMN studies in depression identified deficits in the frontal, but not in the temporal MMN source.28 Although patients with depression did not exhibit significant activation deficits in the auditory cortex, the differences between the 2 patient groups did not reach significance either. On a descriptive level, activation of the auditory cortex in this group situated on an intermediate level between patients with schizophrenia and healthy control subjects. Furthermore, auditory cortex dysfunction in depression has already been suggested by some MEG and behavioral studies.9–11 Hence, a higher number of patients might have led to significant deficits in this group as well.

A growing number of human and animal studies support the view of auditory change detection being a pervasive and hierarchically organized property of the auditory pathway including subcortical processing nodes.14,15,29–31 Extending these findings, the present study revealed for the first time that auditory mismatch deficits in schizophrenia are already present at these subcortical stages. Indeed, different studies revealed structural and functional deficits of the thalamus in schizophrenia, but until now there has been no direct evidence for its contribution to auditory mismatch deficits. Within this framework, some positive symptoms of schizophrenia may arise from aberrant thalamic filtering of novel or salient stimuli.32 Investigating auditory processing during the middle-latency period, Leavitt et al16 suggested thalamic antecedents to early cortical auditory processing deficits in schizophrenia. As a complementary finding, Mäkelä et al33 demonstrated that patients with small thalamic infarctions exhibited decreased MMN generation along with a failure of N1 augmentation similar to that observed in schizophrenia.

Beyond that, our findings support the existence of even earlier deficits in auditory processing in schizophrenia. Indeed, the well-reproduced sensory gating deficit in schizophrenia may reflect deficits at the brainstem level.2,34 Furthermore, a variety of studies have identified abnormal auditory brainstem responses in schizophrenia.35,36 Abnormal brainstem responses and sensory gating deficits have been linked to the presence of auditory hallucinations2,35 which neuroimaging studies have revealed to be associated with an activation of the inferior colliculi.37 Accordingly, auditory hallucinations have been observed after lesions of subcortical stages of the auditory pathway including the inferior colliculi.38 Furthermore, neuropathological studies have identified diencephalic and brainstem lesions to be of special significance for the development of secondary schizophrenia-like psychoses.39 Finally, MRI studies disclosed structural as well as metabolic abnormalities of the right inferior colliculus in schizophrenia, thus further completing the picture.40,41

In accordance with Leavitt et al,16 the path analysis confirmed that subcortical deficits may contribute to the well-established auditory change detection deficit in schizophrenia observed at the cortical level. However, top-down projections from the auditory cortex to the thalamus (corticothalamic projections) and to the inferior colliculus (corticocollicular projections) have been postulated to be relevant for auditory change detection as well.42 We prioritized the bottom-up model over a top-down model based on the observation that a deactivation of the auditory cortex in the rat did not substantially affect the integrity of auditory change detection at the subcortical level.24,43 Moreover, the models allowing for top-down effects exhibited poorer fit indices in our analyses. The mechanisms of top-down influence on change detection need to be further addressed in future studies, eg, using neuromodulation.

Both schizophrenia and major depressive disorder are associated with disturbances of functional connectivity across large-scale brain networks17,44 (see also supplementary discussion S3). In schizophrenia, mismatch deficits have been associated with reduced connectivity between the temporal and prefrontal sources6 and resting state-hypoconnectivity within the somatosensory network.45 In a recent meta-analysis of resting state studies, reduced connectivity within the somatosensory network was indeed identified as a consistent finding in schizophrenia.17 Extending these findings, our study suggests that hypoconnectivity also affects the processing nodes of the auditory pathway which may further contribute to cortical mismatch deficits in both disorders (for more details see supplementary discussion S1).

Limitations

The most important limitation of this study is the relatively small number of participants. Therefore, our findings have to be replicated in a larger and independent sample. Therefore, our findings have to be replicated in a larger and independent sample. Furthermore, subsequent studies should include patients with bipolar disorder and conduct combined EEG-fMRI experiments (see supplementary discussion S2). Moreover, all patients received psychotropic medication and exhibited higher nicotine consumption than healthy participants. Hence, effects mediated by medication or nicotine consumption have to be considered. Nevertheless, MMN deficits in schizophrenia are not influenced by antipsychotics and studies on serotonergic or cholinergic manipulations have yielded inconsistent findings.2 Furthermore, the 2 patient groups did not differ with respect to nicotine consumption. Finally, we did not detect a correlation between activation levels and neuroleptic medication or nicotine doses.

Conclusion

This study revealed for the first time that auditory change detection deficits in schizophrenia already emerged at the subcortical level. These deficits propagated along the auditory pathway and contributed to the well-known deficits at the cortical stage. Moreover, subcortical deficits were specific to schizophrenia. Neuroanatomical considerations of thalamic and brainstem dysfunction have a long tradition in schizophrenia research. Already in the 1970s, neuroscientist Derek Richter stated that “the symptoms of schizophrenia can be related mainly to a disturbance focused on brainstem and diencephalic areas of the brain.”46 Future studies applying spatially highly resolved imaging techniques such as ultra-high field MRI may help to further elucidate brainstem pathology in schizophrenia.

Funding

This research was supported by grants of the Faculty of Medicine of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule (RWTH) Aachen University (START; 121/11 and 143/13), the German Research Foundation (DFG; MA 2631/6-1, IRTG 2150) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; APIC: 01 EE1405A-C).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Brain Imaging Facility of the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research within the Faculty of Medicine at the RWTH Aachen University for their technical support. The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1. Möller HJ. Systematic of psychiatric disorders between categorical and dimensional approaches: Kraepelin’s dichotomy and beyond. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258 (suppl 2):48–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Javitt DC, Freedman R. Sensory processing dysfunction in the personal experience and neuronal machinery of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fitzgerald PJ. Gray colored glasses: is major depression partially a sensory perceptual disorder? J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umbricht D, Krljes S. Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Escera C, Alho K, Winkler I, Näätänen R. Neural mechanisms of involuntary attention to acoustic novelty and change. J Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10(5):590–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaebler AJ, Mathiak K, Koten JW Jr, et al. Auditory mismatch impairments are characterized by core neural dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 5):1410–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim S, Jeon H, Jang KI, Kim YW, Im CH, Lee SH. Mismatch negativity and cortical thickness in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(2):425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erickson MA, Ruffle A, Gold JM. A Meta-analysis of mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: from clinical risk to disease specificity and progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(12):980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tollkötter M, Pfleiderer B, Sörös P, Michael N. Effects of antidepressive therapy on auditory processing in severely depressed patients: a combined MRS and MEG study. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwenzer M, Zattarin E, Grözinger M, Mathiak K. Impaired pitch identification as a potential marker for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takei Y, Kumano S, Hattori S, et al. Preattentive dysfunction in major depression: a magnetoencephalography study using auditory mismatch negativity. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(1):52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Umbricht D, Koller R, Schmid L, et al. How specific are deficits in mismatch negativity generation to schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1120–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kähkönen S, Yamashita H, Rytsälä H, Suominen K, Ahveninen J, Isometsä E. Dysfunction in early auditory processing in major depressive disorder revealed by combined MEG and EEG. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32(5):316–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slabu L, Grimm S, Escera C. Novelty detection in the human auditory brainstem. J Neurosci. 2012;32(4):1447–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cacciaglia R, Escera C, Slabu L, et al. Involvement of the human midbrain and thalamus in auditory deviance detection. Neuropsychologia. 2015;68:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leavitt VM, Molholm S, Ritter W, Shpaner M, Foxe JJ. Auditory processing in schizophrenia during the middle latency period (10-50 ms): high-density electrical mapping and source analysis reveal subcortical antecedents to early cortical deficits. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32(5):339–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dong D, Wang Y, Chang X, Luo C, Yao D. Dysfunction of large-scale brain networks in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(1):168–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):603–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kircher TT, Rapp A, Grodd W, et al. Mismatch negativity responses in schizophrenia: a combined fMRI and whole-head MEG study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schall U, Johnston P, Todd J, Ward PB, Michie PT. Functional neuroanatomy of auditory mismatch processing: an event-related fMRI study of duration-deviant oddballs. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parsons CE, Young KS, Joensson M, et al. Ready for action: a role for the human midbrain in responding to infant vocalizations. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(7):977–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fishman YI, Steinschneider M. Searching for the mismatch negativity in primary auditory cortex of the awake monkey: deviance detection or stimulus specific adaptation? J Neurosci. 2012;32(45):15747–15758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Antunes FM, Malmierca MS. Effect of auditory cortex deactivation on stimulus-specific adaptation in the medial geniculate body. J Neurosci. 2011;31(47):17306–17316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Winer JA. Decoding the auditory corticofugal systems. Hear Res. 2005;207(1-2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 1997;6(3):218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Todd J, Harms L, Schall U, Michie PT. Mismatch negativity: translating the potential. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qiao Z, Yu Y, Wang L, et al. Impaired pre-attentive change detection in major depressive disorder patients revealed by auditory mismatch negativity. Psychiatry Res. 2013;211(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kraus N, McGee T, Littman T, Nicol T, King C. Nonprimary auditory thalamic representation of acoustic change. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72(3):1270–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malmierca MS, Cristaudo S, Pérez-González D, Covey E. Stimulus-specific adaptation in the inferior colliculus of the anesthetized rat. J Neurosci. 2009;29(17):5483–5493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Escera C, Leung S, Grimm S. Deviance detection based on regularity encoding along the auditory hierarchy: electrophysiological evidence in humans. Brain Topogr. 2014;27(4):527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Behrendt RP. Dysregulation of thalamic sensory “transmission” in schizophrenia: neurochemical vulnerability to hallucinations. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3):356–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mäkelä JP, Salmelin R, Kotila M, et al. Modification of neuromagnetic cortical signals by thalamic infarctions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;106(5):433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freedman R, Waldo M, Bickford-Wimer P, Nagamoto H. Elementary neuronal dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1991;4(2):233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lindstrom L, Klockhoff I, Svedberg A, Bergstrom K. Abnormal auditory brain-stem responses in hallucinating schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayashida Y, Mitani Y, Hosomi H, Amemiya M, Mifune K, Tomita S. Auditory brain stem responses in relation to the clinical symptoms of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21(2):177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shergill SS, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Mapping auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braun CM, Dumont M, Duval J, Hamel-Hébert I, Godbout L. Brain modules of hallucination: an analysis of multiple patients with brain lesions. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28(6):432–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davison K. Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: review of literature. Br J Psychiatry 1969;4:113–184. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martinez-Granados B, Martinez-Bisbal MC, Sanjuan J, et al. Study of the inferior colliculus in patients with schizophrenia by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Rev Neurol. 2014;59(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang DH, Kwon KW, Gu BM, Choi JS, Jang JH, Kwon JS. Structural abnormalities of the right inferior colliculus in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;164(2):160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Escera C, Malmierca MS. The auditory novelty system: an attempt to integrate human and animal research. Psychophysiology. 2014;51(2):111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anderson LA, Malmierca MS. The effect of auditory cortex deactivation on stimulus-specific adaptation in the inferior colliculus of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37(1):52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):603–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee M, Hoptman M, Sehatpour P, et al. Neural mechanisms of mismatch negativity (MMN) dysfunction in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2017;22(11):1585–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Richter D. The impact of biochemistry on the problem of schizophrenia. In: Kemali D, Bartholini G, Richter D, eds.. Schizophrenia Today. Oxford, England: Pergamon; 1976:71–83. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.