Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between atrial fibrillation (AF) and total and regional brain volumes among participants in the community-based Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive study (ARIC-NCS). A total of 1,930 participants (130 with AF) with a mean age of 76.3 ± 5.2, who underwent 3T brain MRI scans in 2011 to 2013 were included. Prevalent AF was ascertained from study ECGs and hospital discharge codes. Brain volumes were measured using FreeSurfer image analysis software. Markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease included lobar microhemorrhages, subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical infarcts, subcortical infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and volume of white matter hyperintensities. Linear regression models were used to assess the associations between AF status and brain volumes. In adjusted analyses, AF was not associated with markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. However, AF was associated with smaller regional brain volumes (including temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes; deep gray matter; Alzheimer disease signature region; and hippocampus [all p <0.05]) after controlling for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. Subgroup analysis revealed a significant interaction between AF and total brain volume with respect to age (p = 0.02), with associations between AF and smaller brain volumes being stronger for older individuals. In conclusion, AF was associated with smaller brain volumes, and the association was stronger among older individuals. This finding may be related to the longer exposure period of the older population to AF or the possibility that older people are more susceptible to the effects of AF on brain volume.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most commonly sustained cardiac arrhythmia, and its prevalence increases dramatically with age.1 Emerging evidence suggests that AF is associated with cognitive impairment.2–5 Even though increasing evidence has shown that cognitive performance is worse in patients with AF compared with those without, studies investigating the potential underlying brain morphometric changes in this patient population are scarce.4,6,7,8,9 Given the conflicting evidence, it is important to understand the relation between AF and brain structure, as it might provide additional insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of cognitive impairment in AF patients. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between AF and total and regional brain volumes among participants in the community-based Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive study (ARIC-NCS). We hypothesized that prevalent AF is associated with total or regional brain volumes and that these associations were independent of subclinical cerebrovascular disease.

Methods

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study is a community-based prospective cohort of 15,792 participants aged 45 to 64 years at the time of their enrollment in 1987 to 1989. Participants were recruited from the following 4 US communities: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland.11

The ARIC-NCS is an ancillary study to the main ARIC study, where all ARIC participants attending the 2011 to 2013 exam (visit 5) were invited to undergo an extensive cognitive evaluation and, in a selected subset, a more detailed assessment including a brain MRI.12 Participants were invited to complete a brain MRI scan if they had any evidence of cognitive impairment, those with a previous ARIC study brain MRI scan, as well as a stratified random sample of the remaining participants, with strata based on age and study site. Sampling weights were used to account for the stratified random sampling that was used to select participants from each ARIC site during Visit 5 into the ARIC MRI sample. This enabled our site-specific analyses to be interpreted as the association that would be observed in the full Visit 5 ARIC sample at each site.

The ARIC study has been approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions. All participants gave written informed consent at each study visit.

At ARIC-NCS, brain MRI scans were performed by using 3T brain MRI following identical protocols at each study site.13 All scans included sagittal T1-weighted, magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo MP-RAGE (1.2-mm slices), axial gradient recalled echo T2-weighted imaging (T2*GRE) (4-mm slices), axial T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (5-mm slices). Data were processed by the ARIC MRI Reading Center at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Brain volumes were measured on MPRAGE sequences using image analysis software (FreeSurfer; http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu).14 Subclinical cerebrovascular disease including white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume and infarcts were assessed on T2 FLAIR sequences, and microhemorrhages were assessed on T2*GRE sequences. Lacunar infarcts were defined as subcortical lesions with central hypointensity >3 mm and hyperintensity ≤20 mm in maximum dimension on T2 FLAIR located in the caudate, lenticular nucleus, internal capsule, thalamus, brainstem, deep cerebellar white matter, centrum semiovale, or corona radiate.15 Cortical infarcts were defined as lesions of >20 mm in minimum diameter on T2 FLAIR.16 Microhemorrhages were lesions of ≤5 mm in maximum diameter on T2*GRE sequences and were divided into lobar and subcortical microhemorrhages.15 The brain volumes used as outcomes in our study included: total brain volume, lobar volumes (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital), deep gray subcortical structure volume (defined as the total volume of the thalamus, caudate, putamen, and globus pallidum), total volume of an Alzheimer disease signature region (defined as the total volume of parahippocampal, entorhinal, and inferior parietal lobules; hippocampus; precuneus; and cuneus),17 and hippocampal volume.

The ascertainment of AF has been previously reported.18,19 Briefly, AF was identified by 3 sources including ECGs from follow-up exams, hospital discharge records, and death certificates. ECGs during follow-up exams were done with MAC PC personal Cardiographs, where all ECGs were transmitted to the ARIC ECG reading center for coding, interpretation, and storage. A trained cardiologist would confirm the presence of AF by visually reading the recordings of ECGs automatically coded as AF. Also, the information of hospitalization was obtained during the annual follow-up interview and from surveillance of local hospitals. A trained abstractor would access the hospital discharge records and manually record all of the diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. AF was defined with codes 427.31 or 427.32, not associated with open heart surgery codes in any hospitalization occurring during follow-up before visit 5.18 ARIC has continuous surveillance of participant hospitalizations.18

With the exception of education which was assessed only at visit 1, covariate information was obtained at visit 5 (2011 to 2013). These variables included age at visit 5, gender, race/center (black—Mississippi, black—North Carolina, white—North Carolina, white—Maryland, white—Minnesota), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate or general equivalency diploma, or beyond high school), smoking status (current, former, never), and APOE ε4 status (by TaqMan assay; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). APOE ε4 carriers, genotyped previously, were defined based on the number of ε4 alleles (0, 1, or 2). Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140, diastolic blood pressure ≥90, or use of anti-hypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL, a nonfasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL, using medication for diabetes mellitus, or self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Heart failure, coronary heart disease, and stroke were defined based on presence of adjudicated events according to previously published criteria.20–22

We reported means with SDs or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables. All analyses incorporated sampling weights in order to account for the ARIC brain MRI sampling strategy. Brain volumes were expressed as percentage of total intracranial volume to adjust for between subject differences in head size. Multivariable regression models were used to assess the association between AF status with brain volumes and subclinical cerebrovascular disease. Each brain volume was scaled on the basis of its standard deviation to facilitate comparison of the magnitude of association across brain regions in regression models. Distribution of WMH volume was highly skewed in this population, and was therefore log base 2 (log2) transformed for normality. The multivariable models used in the present study were constructed as follows:

Model 1 was adjusted for demographics (age, gender, race and center, and education) and total intracranial volume. Model 2 was adjusted for all variables in Model 1 and also cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, hypertension), prevalent cardiovascular disease (past history of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke) and APOE4. Model 3 included all variables in Model 2 in addition to markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease (lobar microhemorrhages, subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical infarcts, subcortical infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and Log2WMH).

In sensitivity analyses, we estimated the association between AF status and total brain volumes for subgroups of interest including age category, gender, race, cardiovascular risk factors and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Multiplicative interactions were formally tested using interaction terms. All sensitivity analyses were conducted using the fully adjustment model (Model 3). Two-tailed p values <0.05 were used for significance testing. All statistical analyses were done using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP; College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the ARIC participants at visit 5 who underwent brain MRI scans. The analysis cohort consisted of 1,930 participants (mean age, 76.3 ± 5.2 years at visit 5; 59% women and 28.6% black), of which 130 (7%) had a diagnosis of AF. Compared with those without AF, participants with AF were older, more often men and white, and had a higher prevalence of coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by prevalent AF status, ARIC-NCS 2011 to 2013

| Variables | Atrial fibrillation | |

|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1,800) | Yes (n = 130) | |

| Age, mean (years) | 76 ± 5 | 78 ± 5 |

| Men | 708 (39.3%) | 71 (54.6%) |

| Whites | 1263 (70.2%) | 109 (83.8%) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 258 (14.3%) | 21 (16.2%) |

| High school, GED, or vocational school | 738 (41.0%) | 51 (39.2%) |

| College or graduate or professional school | 802 (44.6%) | 58 (44.6%) |

| Current smoker | 95 (5.3%) | 5 (4%) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 1345 (75.4%) | 94 (73.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 548 (30.6%) | 44 (34.1%) |

| Coronary heart disease | 164 (9.3%) | 27 (20.9%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 41 (2.3%) | 23 (17.7%) |

| Stroke | 56 (3.1%) | 9 (6.9%) |

| APOE4 genotype | ||

| 0 alleles | 1,224 (70.3%) | 92 (74.8%) |

| 1 or 2 alleles | 515 (29.7%) | 31 (25.2%) |

| Markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease | ||

| Lobar microhemorrhages | 153 (8.6) | 19 (14.6) |

| Subcortical microhemorrhages | 352 (19.9) | 26 (20) |

| Cortical infarcts | 127 (7.1) | 11 (8.5) |

| Subcortical infarcts | 335 (18.6) | 29 (22.3) |

| Lacunar infarcts | 326 (18.1) | 29 (22.3) |

| Volume of white matter hyperintensity (cm3), Median (IQR) | 11.7 (6.4–21.6) | 14.8 (8.0–26.0) |

| Brain Volumes (cm3)*, % (SD) | ||

| Total brain | 73.5 (4) | 71.4 (4) |

| Frontal lobe | 10.9 (0.7) | 10.6 (0.8) |

| Temporal lobe | 7.4 (0.6) | 7.1 (0.6) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.3) |

| Parietal lobe | 7.6 (0.5) | 7.4 (0.6) |

| Deep gray matter | 3.1 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2) |

| Alzheimer disease signature | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.3) |

| Hippocampus | 0.50 (0.07) | 0.46 (0.08) |

GED = general equivalency diploma.

Adjusted as percentage of total intracranial volume

Table 2 describes the associations between AF and markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease including lobar and subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical, subcortical, and lacunar infarcts, and WMH volumes. None of the markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease were independently associated with AF after adjustment for demographics (age, gender, and race) (Model 1), or cardiovascular risk factors, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and APOE4 (Model 2).

Table 2.

Weighted adjusted cross-sectional associations of AF with measures of subclinical cerebrovascular disease, ARIC-NCS, 2011 to 2013

| Markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease | Model 1 Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Model 2 Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without AF(n = 1,800) | AF (n = 130) | p Value | Without AF(n = 1,800) | AF(n = 130) | p Value | |

| Lobar microhemorrhages | 1 (Reference) | 1.52 (0.82–2.81) | 0.17 | 1 (Reference) | 1.06 (0.49–2.27) | 0.87 |

| Subcortical microhemorrhages | 1 (Reference) | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 0.86 | 1 (Reference) | 1.01 (0.57–1.78) | 0.97 |

| Cortical infarcts | 1 (Reference) | 0.97 (0.49–1.91) | 0.94 | 1 (Reference) | 1.11 (0.53–2.33) | 0.76 |

| Subcortical infarcts | 1 (Reference) | 1.16 (0.70–1.92) | 0.55 | 1 (Reference) | 0.97 (0.52–1.81) | 0.93 |

| Lacunar infarcts | 1 (Reference) | 1.20 (0.72–1.99) | 0.47 | 1 (Reference) | 1.02 (0.55–1.89) | 0.94 |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |||||

| WMH volume, per doubling | 0 (Reference) | 0.14 (−0.7, 0.37) | 0.20 | 0 (Reference) | 0.12 (−0.11, 0.37) | 0.29 |

Model 1 adjusted for age, gender, race, and education. Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 + cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, and hypertension), prevalent cardiovascular disease (past history of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), and APOE4.

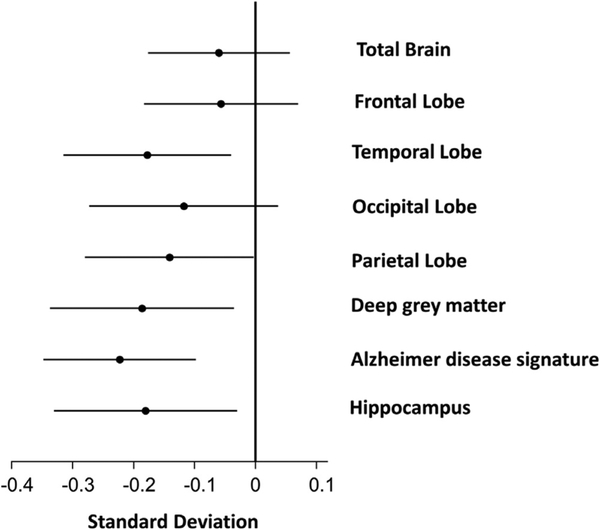

As shown in Table 3, significant inverse associations were present between prevalent AF and both total and regional brain volumes after adjusting for potential confounders including total intracranial volume and baseline demographics (Model 1), and cardiovascular risk factors, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and APOE4 (Model 2). Further adjustments for markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease (Model 3) did not attenuate the association between the brain volumes and AF (Figure 1). The strongest associations were present for volumes of the Alzheimer disease signature region, followed by volumes of deep gray matter and the hippocampus (Table 3, Figure 1). For most brain regions, subjects with AF had approximately 0.2 SD lower regional brain volumes than those without AF (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weighted adjusted cross-sectional associations of AF with brain MRI parameters

| Brain volumes* | Without AF(n = 1,800) | AF (n = 130) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Model 1 | |||

| Total brain | 0 (Reference) | −0.09 (−0.20, 0.01) | 0.08 |

| Frontal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.06 (−0.18, 0.05) | 0.26 |

| Temporal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.15 (−0.28, −0.01) | 0.02 |

| Occipital lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.16 (−0.30, −0.01) | 0.03 |

| Parietal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.18 (−0.31, −0.05) | 0.007 |

| Deep gray matter | 0 (Reference) | −0.21 (−0.35, −0.06) | 0.003 |

| Alzheimer disease signature | 0 (Reference) | −0.24 (−0.36, −0.11) | <0.001 |

| Hippocampus | 0 (Reference) | −0.16 (−0.3, −0.02) | 0.02 |

| B. Model 2 | |||

| Total brain | 0 (Reference) | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04) | 0.23 |

| Frontal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.05) | 0.26 |

| Temporal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.18 (−0.32, −0.05) | <0.001 |

| Occipital lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.16 (−0.32, −0.01) | 0.03 |

| Parietal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.17 (−0.30, −0.03) | 0.01 |

| Deep gray matter | 0 (Reference) | −0.17 (−0.32, −0.02) | 0.02 |

| Alzheimer disease signature | 0 (Reference) | −0.24 (−0.37, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Hippocampus | 0 (Reference) | −0.19 (−0.3, −0.04) | 0.01 |

| C. Model 3 | |||

| Total brain | 0 (Reference) | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04) | 0.21 |

| Frontal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.06 (−0.19, 0.05) | 0.27 |

| Temporal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.18 (−0.31, −0.04) | 0.010 |

| Occipital lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.008) | 0.039 |

| Parietal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.17 (−0.30, −0.03) | 0.0139 |

| Deep gray matter | 0 (Reference) | −0.19 (−0.34, −0.04) | 0.012 |

| Alzheimer disease signature | 0 (Reference) | −0.24 (−0.37, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Hippocampus | 0 (Reference) | −0.18 (−0.3, −0.03) | 0.020 |

Model 1. Adjusted for total intracranial volume and demographics (age, gender, race, and education). Model 2. Adjusted for Model 1 + cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, and hypertension), prevalent cardiovascular disease (past history of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), and APOE4. Model 3. Adjusted for Model 2 + lobar microhemorrhages, subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical infarcts, subcortical infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and Log2 WMH.

Bold values indicating a p value < 0.05.

SD units. Definition of 1 SD: total brain volume 108.1 cm3, frontal lobe volume 16.0 cm3, temporal lobe volume 11.7 cm3, occipital lobe volume 5.5 cm3, parietal lobe volume 12.6 cm3, deep gray matter volume 4.3 cm3, Alzheimer disease signature region volume 7.0 cm3, hippocampal volume 1.0 cm3.

Figure 1.

Associations between presence of AF with brain MRI parameters. Model adjusted for total intracranial volume, demographics (age, gender, race, and education), cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, hypertension), prevalent cardiovascular disease (past history of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), APOE4, and measures of subclinical cerebrovascular disease (lobar microhemorrhages, subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical infarcts, subcortical infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and Log2 WMH).

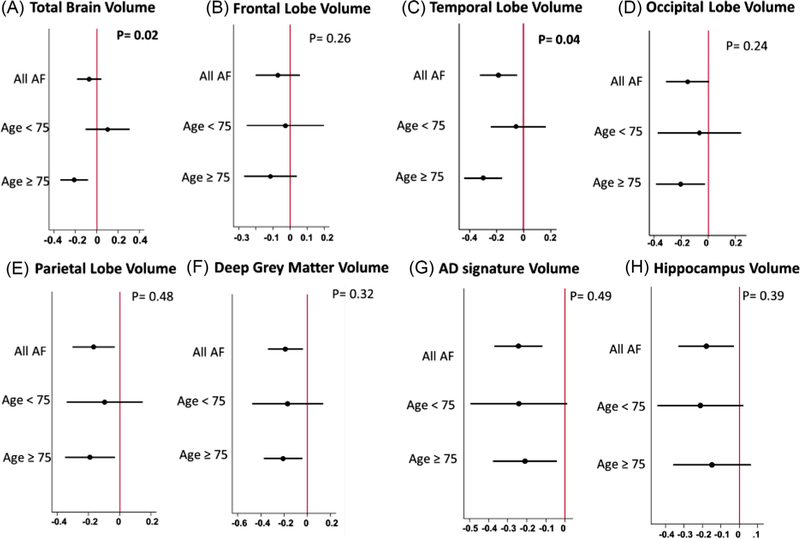

Analysis of interaction, adjusted for Model 3 covariates, produced little evidence of significant heterogeneity overall. However, associations between AF and total brain volumes were stronger for older participants compared with younger participants (p for interaction = 0.02). In subgroup analysis, no statistically significant associations were found between AF and any of the brain volumes among participants younger than 75 years of age. However, for older participants, presence of AF was strongly associated with smaller brain volumes (p for all <0.01), except for hippocampal (p = 0.21) and frontal volumes (p = 0.32, Figure 2). No significant interactions were present for other potential effect modifiers, including gender, race, cardiovascular risk factors, or prevalent cardiovascular disease Supplemental Figure). Finally, in order to investigate the role of time since AF diagnosis on brain volumes, patients with AF were divided into 2 groups (long vs short time since AF diagnosis) based on the median duration from AF diagnosis to brain imaging measurements. As shown in Table 4, after adjusting for intracranial volume, baseline demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, prevalent cardiovascular disease, APOE4, and markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease, there were no significant differences between patients with long versus short AF duration with respect to total and regional brain volumes.

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis of the association between AF status and brain volumes by age. p = p value for interaction.

Table 4.

Weighted adjusted associations of time since AF diagnosis with brain MRI parameters (n = 130)

| Brain volumes* | AF with short time since diagnosis (<7 years) (n = 60) | AF with long time since diagnosis (≥7 years) (n = 70) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total brain | 0 (Reference) | −0.11 (−0.33, 0.15) | 0.32 |

| Frontal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.26 (−0.61, 0.09) | 0.14 |

| Temporal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.23 (−0.58, 0.11) | 0.17 |

| Occipital lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.18 (−0.52, 0.15) | 0.27 |

| Parietal lobe | 0 (Reference) | −0.12 (−0.49, 0.24) | 0.49 |

| Deep gray matter | 0 (Reference) | −0.06 (−0.46, 0.33) | 0.73 |

| Alzheimer disease signature | 0 (Reference) | −0.25 (−0.55, 0.06) | 0.10 |

| Hippocampus | 0 (Reference) | −0.39 (−0.89, 0.09) | 0.11 |

Model adjusted for total intracranial volume, demographics (age, gender, race, and education), cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, and hypertension), prevalent cardiovascular disease (past history of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), APOE4, and measures of subclinical cerebrovascular disease (lobar microhemorrhages, subcortical microhemorrhages, cortical infarcts, subcortical infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and Log2 WMH).

SD units. Definition of 1 SD: total brain volume 108.1 cm3, frontal lobe volume 16.0 cm3, temporal lobe volume 11.7 cm3, occipital lobe volume 5.5 cm3, parietal lobe volume 12.6 cm3, deep gray matter volume 4.3 cm3, Alzheimer disease signature region volume 7.0 cm3, hippocampal volume 1.0 cm3.

Discussion

In a large community-based cohort of blacks and whites, we found strong associations between AF and smaller regional brain volumes, whereas no associations were found between AF and indices of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. Such findings remain after adjusting for demographic information, cerebrovascular risk factors, and markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. The associations between AF and smaller brain volumes were strongest among older individuals which could be a result of the longer duration of exposure of the brain to the effects of AF in older people, or it may suggest a higher susceptibility of this age group to the effects of AF on brain structure.

Previous studies investigating the role of AF on the brain structure and morphology have reported conflicting results. Our results are in concordance with the largest brain MRI study, carried on in Iceland, in which the authors found AF to be associated with lower total brain volume, as well as gray matter and white matter volumes.4 However, these findings are in contrast with a few previous studies,10,23 which failed to show such associations between AF and lower brain volumes. However, in a more recent study from the Framingham Offspring cohort, the authors found that frontal lobe volumes were smaller in patients with AF compared with the general population even after accounting for vascular risk factors and APOE4 status.8 These differences could be partly due to the age of participants included in each study. The mean age of our study was 76 years, close to the Icelandic study which included participants with a mean age older than 75 years. In contrast, the participants in studies who did not show significant associations between AF and brain volumes were, on average, more than a decade younger than our cohort. Our subgroup analysis further supports the notion that the effect of AF on brain structures could be age dependent given the fact that such associations were not statistically significant among participants younger than 75 years of age.

The mechanisms by which AF causes changes in the brain structure and morphology are poorly understood. The increased burden of co-morbidities among patients with AF may partly explain smaller brain volumes in this population. Both hypertension and diabetes, which are more common among patients with AF, have been linked to lower total brain, gray matter, and hippocampal volumes.24,25 In our results, however, adjustment for these factors had very little effect on the point estimates, and there were no significant interactions among various co-morbidities that could potentially modify the relation between AF and brain volumes. Another possible explanation is that AF causes multiple microembolisms to the brain. These microemboli can subsequently lead to microinfarcts and eventually brain atrophy. However, further controlling for markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease including microhemorrhages and microinfarcts did not alter the associations between AF and brain volumes in the present study. Furthermore, none of these factors were independently associated with AF after adjusting for baseline demographics. Finally, cerebral hypoperfusion during AF, perhaps related to the beat-to-beat variation in stroke volume could potentially play a part in brain atrophy. In a recent study of 2,291 individuals from the general population, patients with persistent AF had the lowest cerebral blood flow as well as the lowest relative brain volumes.26 Cerebral blood flow has also shown to increase after electric cardioversion of AF.27 Decreased total cerebral blood flow has shown to have a greater negative effect on the gray matter than white matter, which could reflect the higher metabolic demand of the gray matter.28 Our findings support this hypothesis as the largest areas affected by AF were the deep gray matter and hippocampal volumes. Future prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether restoration of sinus rhythm in individual with AF would lead to improved brain perfusion.

The major strengths of our study include the extensive and rigorous measurement of covariates in a large number of well-described community-dwelling subjects with brain MRI scans, which allowed us to perform comprehensive statistical adjustment, and therefore reducing potential confounding. The brain MRI data were obtained from 3T scanners and were analyzed for total and regional brain volumes as well as microhemorrhages, cortical and lacunar infarcts, and WMH volumes. Our study also has some notable limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes any inference on direct cause and effect. Second, we were not able to determine the type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF), and therefore could not investigate the relation between AF type and brain volumes.

Our findings based on a large population-based cohort study provide evidence that prevalent AF is associated with lower total and regional brain volumes independent of demographics, cerebrovascular risk factors, and markers of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. These associations were stronger for older individuals, suggesting that older people may be more susceptible to the effects of AF on brain volumes. Future prospective studies are needed to determine if maintenance of sinus rhythm could attenuate brain atrophy in this group of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) for their important contributions.

Funding: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, and HHSN268201700004I). Neurocognitive data are collected by 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, and 2U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA, and NIDCD), and with previous brain MRI examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI. Additional support was provided by American Heart Association award 16EIA26410001 (Alonso) and the National Institutes of Health awards T32 HL130025 (Moazzami) and K24 HL148521 (Alonso).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.010.

References

- 1.Magnani JW, Rienstra M, Lin H, Sinner MF, Lubitz SA, McManus DD, Dupuis J, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ. Atrial fibrillation: current knowledge and future directions in epidemiology and genomics. Circulation 2011;124:1982–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunch TJ, Weiss JP, Crandall BG, May HT, Bair TL, Osborn JS, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, Lappe DL, Day JD. Atrial fibrillation is independently associated with senile, vascular, and Alzheimer’s dementia. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen LY, Lopez FL, Gottesman RF, Huxley RR, Agarwal SK, Loehr L, Mosley T, Alonso A. Atrial fibrillation and cognitive decline-the role of subclinical cerebral infarcts: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke 2014;45:2568–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefansdottir H, Arnar DO, Aspelund T, Sigurdsson S, Jonsdottir MK, Hjaltason H, Launer LJ, Gudnason V. Atrial fibrillation is associated with reduced brain volume and cognitive function independent of cerebral infarcts. Stroke 2013;44:1020–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LY, Norby FL, Gottesman RF, Mosley TH, Soliman EZ, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Folsom AR, Coresh J, Alonso A. Association of atrial fibrillation with cognitive decline and dementia over 20 years: the ARIC-NCS (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive study). J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalantarian S, Stern TA, Mansour M, Ruskin JN. Cognitive impairment associated with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santangeli P, Di Biase L, Bai R, Mohanty S, Pump A, Cereceda Brantes M, Horton R, Burkhardt JD, Lakkireddy D, Reddy YM, Casella M, Dello Russo A, Tondo C, Natale A. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of incident dementia: a meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 2012;9: 1761–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piers RJ, Nishtala A, Preis SR, DeCarli C, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Au R. Association between atrial fibrillation and volumetric magnetic resonance imaging brain measures: Framingham Offspring Study. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:2020–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knecht S, Oelschlager C, Duning T, Lohmann H, Albers J, Stehling C, Heindel W, Breithardt G, Berger K, Ringelstein EB, Kirchhof P, Wersching H. Atrial fibrillation in stroke-free patients is associated with memory impairment and hippocampal atrophy. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2125–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Elias MF, Au R, Kase CS, D’Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology 2004;63:1591–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ARIC investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129: 687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, Wruck LM, Windham BG, Coker L, Schneider AL, Hengrui S, Alonso A, Coresh J, Albert MS, Mosley TH Jr.. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive study (ARIC-NCS). Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;2:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knopman DS, Griswold ME, Lirette ST, Gottesman RF, Kantarci K, Sharrett AR, Jack CR Jr., Graff-Radford J, Schneider AL, Windham BG, Coker LH, Albert MS, Mosley TH Jr., ARIC Neurocognitive Investigators. Vascular imaging abnormalities and cognition: mediation by cortical volume in nondemented individuals: atherosclerosis risk in communities-neurocognitive study. Stroke 2015;46:433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002;33: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, Lindley RI, O’Brien JT, Barkhof F, Benavente OR, Black SE, Brayne C, Breteler M, Chabriat H, Decarli C, de Leeuw FE, Doubal F, Duering M, Fox NC, Greenberg S, Hachinski V, Kilimann I, Mok V, Oostenbrugge R, Pantoni L, Speck O, Stephan BC, Teipel S, Viswanathan A, Werring D, Chen C, Smith C, van Buchem M, Norrving B, Gorelick PB, Dichgans M, nEuroimaging STfRVco. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Przybelski SA, Shiung MM, Whitwell JL, Negash S, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, O’Brien PC, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr.. Risk of dementia in MCI: combined effect of cerebrovascular disease, volumetric MRI, and 1H MRS. Neurology 2009;72:1519–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, Sperling RA, Killiany RJ, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Blacker D, Detoledo-Morrell L. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology 2011;76:1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Chamberlain AM, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African-Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J 2009;158:111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misialek JR, Rose KM, Everson-Rose SA, Soliman EZ, Clark CJ, Lopez FL, Alonso A. Socioeconomic status and the incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and blacks: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Cooper LS, Conwill DE, Clegg L, Wang CH, Heiss G. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1998;339:861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, Copper LS, Shahar E. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults: 9-year follow-up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. Stroke 1999;30:736–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, Poirier V, O’Leary DH, Gardin JM, Fried LP, Steinberg EP, Bryan RN. Magnetic resonance abnormalities and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The cardiovascular health study. Stroke 1994;25:318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiseman RM, Saxby BK, Burton EJ, Barber R, Ford GA, O’Brien JT. Hippocampal atrophy, whole brain volume, and white matter lesions in older hypertensive subjects. Neurology 2004;63:1892–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espeland MA, Bryan RN, Goveas JS, Robinson JG, Siddiqui MS, Liu S, Hogan PE, Casanova R, Coker LH, Yaffe K, Masaki K, Rossom R, Resnick SM, Group W- MS. Influence of type 2 diabetes on brain volumes and changes in brain volumes: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies. Diabetes Care 2013;36:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardarsdottir M, Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Rokita H, Launer LJ, Gudnason V, Arnar DO. Atrial fibrillation is associated with decreased total cerebral blood flow and brain perfusion. Europace 2017;20: 1252–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen P, Kastrup J, Videbaek R, Boysen G. Cerebral blood flow before and after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1989;9:422–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payabvash S, Souza LC, Wang Y, Schaefer PW, Furie KL, Halpern EF, Gonzalez RG, Lev MH. Regional ischemic vulnerability of the brain to hypoperfusion: the need for location specific computed tomography perfusion thresholds in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2011;42:1255–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.