Abstract

Metatranscriptomics is a powerful method for studying the composition and function of complex microbial communities. The application of metatranscriptomics to multi-species parasite infections is of particular interest, as research on parasite evolution and diversification has been hampered by technical challenges to genome-scale DNA sequencing. In particular, blood parasites of vertebrates are abundant and diverse though they often occur at low infection intensities and exist as multi-species infections, rendering the isolation of genomic sequence data challenging. Here, we use birds and their diverse haemosporidian parasites to illustrate the potential for metatranscriptome sequencing to generate large quantities of genome-wide sequence data from multiple blood parasite species simultaneously. We used RNA-Seq on 24 blood samples from songbirds in North America to show that metatranscriptomes can yield large proportions of haemosporidian protein-coding gene repertoires even when infections are low-intensity (<0.1% red blood cells infected) and consist of multiple parasite taxa. By bioinformatically separating host and parasite transcripts and assigning them to the haemosporidian genus of origin, we found that transcriptomes detected ~23% more total parasite infections across all samples than were identified using microscopy and DNA barcoding. For single-species infections, we obtained data for upwards of 1,300 loci from samples with as low as 0.03% parasitemia, with the number of loci increasing with infection intensity. In total, we provide data for 1,502 single-copy orthologous loci from a phylogenetically-diverse set of 33 haemosporidian mitochondrial lineages. The metatranscriptomic approach described here has the potential to accelerate ecological and evolutionary research on haemosporidians and other diverse parasites.

Keywords: co-infection, Leucocytozoon, malaria parasite, Plasmodium, Parahaemoproteus, RNA-Seq

Introduction

Metatranscriptomics, the simultaneous study of the gene expression of multiple organisms within a single environment, has become increasingly popular in recent years as researchers seek to augment single-locus surveys of microbial communities with functional characterization from across the genome. Metatranscriptomics has been used to study a wide array of microbial systems, including the diversity and function of crop soil symbiont communities (Turner et al., 2013), resource partitioning within phytoplankton communities (Alexander et al., 2015), and the diversity of viruses within their hosts (Shi et al., 2018). The potential for metatranscriptomics to generate data from all taxa within an environment (and not just those within a targeted lineage as is often done using metabarcoding approaches) as well as provide a comprehensive overview of the loci that are being transcribed and their expression levels has made metatranscriptomics an important addition to the toolkit of researchers in ecology and evolutionary biology.

One promising use of metatranscriptomics is for the development of genomic resources for taxonomic groups that are poorly studied at the genomic level. Though recent advances in DNA sequencing technologies have led to an explosion of sequence data from across the tree of life (Koepfli et al., 2015; Parks et al. 2017), the taxonomic distribution of sequencing efforts has been biased towards a subset of its major branches (Cunningham et al., 2019). As a result, the genomic resources available for many lineages have seen little growth in recent years despite ever more powerful tools at our disposal. The difficulties of generating genome-wide sequencing data have been particularly pronounced for some diverse parasite groups that are often characterized by poorly known natural histories, complex life cycles, or close associations with host tissues that make complete isolation of the parasite problematic (Palinauskas et al., 2013). Intracellular parasites pose especially difficult challenges, as it is often nearly impossible to isolate their DNA without disproportionate representation of host sequences (Videvall, 2019). Parasites also commonly occur as diverse infracommunities of multiple parasite species within a single host individual (Vaumourin et al., 2015), increasing the difficulty of associating DNA sequence data with individual parasite species. Metatranscriptomics has the potential to address some of these limitations by producing a higher ratio of parasite to host sequence data than whole genome sequencing, and facilitating the separation of host and parasite data in silico by focusing on coding sequences. The potential for metatranscriptomics to be useful as a tool to study parasites has been illustrated by several studies that have discovered high proportions of parasite contigs in host transcriptome assemblies (Borner et al., 2017; Lopes et al., 2017; Pauli et al., 2015; Santos et al., 2018; Videvall et al., 2017), suggesting potential for this method to be useful in a targeted manner for generating parasite genomic data. However, thus far transcriptome sequencing has not been widely used to study naturally-occurring, multi-species parasite infections sampled from across diverse host communities.

Birds and their blood parasites in the order Haemosporida (phylum Apicomplexa) are a convenient group with which to test the utility of using metatranscriptomics in a targeted manner to study endoparasites, as avian haemosporidians are abundant and diverse throughout the world (Bensch et al., 2009). The avian haemosporidians include the ‘malaria parasites’ in the genus Plasmodium, as well as the genera Haemoproteus, Leucocytozoon, and Parahaemoproteus (Valkiūnas, 2004). Avian haemosporidians have become an emerging system for the study of host-parasite interactions, as they exhibit wide variation in host specificity and host range, with phylogenetically conserved life cycles that appear to have undergone only a few major transitions during their long evolutionary history (Galen et al., 2018a). Avian haemosporidians can also have important fitness effects on their hosts, potentially reducing host fecundity and lifespan (Asghar et al., 2015; Lachish et al., 2011).

Despite the importance of haemosporidians in bird communities and their popularity in studies of host-parasite interactions (Bensch et al., 2009), little research has been done on avian haemosporidians at the genomic level. Currently, just three genomes (two Plasmodium and one Haemoproteus [Parahaemoproteus]) and five transcriptomes (three Plasmodium, one Haemoproteus, and one Leucocytozoon) have been sequenced from avian haemosporidians (Videvall, 2019), despite the existence of what is likely to be thousands of species-level lineages worldwide (Bensch et al., 2009). To date, nearly all studies of avian haemosporidians have relied on sequencing a short cytochrome b (cytb) barcode that is of limited utility for identifying species-level lineages (Galen et al., 2018b; Hellgren et al., 2015). Whole-genome sequencing protocols have been proposed for some avian haemosporidian species (Böhme et al., 2018; Palinauskas et al., 2013), though these methods are currently most useful in laboratory settings and are difficult to apply to the sampling of birds in field conditions. DNA sequence capture protocols have recently been applied to study avian haemosporidians (Barrow et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018), though currently this approach has only been developed for specific haemosporidian species or lineages and at most for 1,000 loci. Additional means of generating large quantities of genomic data that do not depend on existing resources are still needed because studies of parasite biology continue to be stifled by dependence on DNA barcodes or small Sanger-sequenced datasets that provide insufficient resolution on processes of molecular evolution and diversification. The lack of genome-scale data for the avian haemosporidians reflects the availability of genomic resources for the entire phylum Apicomplexa broadly (Morrison, 2009), as this lineage has been estimated by some authors to contain upwards of 163 million species globally (Larsen et al., 2017), yet genomic data is only available for a relatively small number of species that have medical or veterinary importance.

Here we test an approach, from field collection to bioinformatic processing, that enables isolation of a large proportion of the protein-coding gene repertoire from haemosporidian blood parasites that occur in wild birds. We found that sequencing blood metatranscriptomes from infected birds generated data for thousands of haemosporidian protein-coding genes per sample, greatly expanding upon the resources currently available for studies of ecology and evolution of these parasites. The approach was successful even when infections were low-intensity and consisted of species from multiple haemosporidian genera. The sequenced transcriptomes revealed a diversity of haemosporidian co-infections that were not detected using standard approaches, exhibiting the power of genome-scale approaches generally, and metatranscriptomics specifically, to provide a higher resolution view of host-parasite interactions.

Materials and Methods

Sample acquisition and preservation

We collected blood samples from songbird (order Passeriformes) hosts at three locations in the United States (Table 1), under appropriate state and federal permits (see Acknowledgements). We collected approximately 20–50 μl of blood from each bird in heparinized microhematocrit tubes, which was immediately expelled directly into 500 μl of RNALater and homogenized by shaking vigorously for several seconds. Blood samples were then maintained at approximately 4° C for up to 2 weeks in the field, after which they were stored at −20° C until RNA isolation. Blood smears for each individual were made from whole blood prior to storage in RNALater for morphological study and quantification of parasites. Birds were prepared as vouchered specimens with frozen tissues and accessioned in the American Museum of Natural History or Museum of Southwestern Biology (Dryad Digital Repository Appendix 1).

Table 1.

Samples selected for transcriptome sequencing. Shown are the host family and host species of each sample, results of microscopic screening for blood parasites and percent infection (parasitemia), results of cytochrome b (cytb) screening for haemosporidians with the names of sequenced cytb lineages, the total number of transcripts that were assembled by Trinity, and the proportion of total transcripts that ContamFinder identified as being from haemosporidian parasites. Novel haemosporidian cytb haplotypes are denoted with an asterisk.

| Sample | Host family | Host species | Microscopy results (% parasitemia) | Cytb barcoding results | Transcripts (All) |

Transcripts (Haemosporidian) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOT23227 | Fringillidae | Loxia leucoptera | Leu: 0.03 |

Leu: LOXLEU02, ROFI06 |

128,503 | 12,022 (9.4%) |

| Para: 2.09 | Para: SISKIN1 | |||||

| DOT23232 | Fringillidae | Loxia leucoptera | Para: 1.65 | Para: SISKIN1 | 143,804 | 9,511 (6.6%) |

| DOT23233 | Fringillidae | Loxia leucoptera | Leu: 0.14 | Leu: CB1, ROFI06 | 176,459 | 5,820 (3.3%) |

| DOT23244 | Turdidae | Turdus migratorius | Leu: 0.08 | Leu: TUMIG11 | 106,598 | 4,860 (4.6%) |

| Para: 0.07 | Para: TURDUS2 | |||||

| DOT23258 (blood) |

Passerellidae | Spizelloides arborea | Leu: 0.19 | Leu: ZOLEU02 | 181,509 | 14,289 (7.87%) |

| Para: 1.48 | Para: SPIARB01 | |||||

| DOT23258 (liver) |

Passerellidae | Spizelloides arborea | 159,856 | 3,967 (2.48%) | ||

| DOT23258 (total) |

Passerellidae | Spizelloides arborea | 264,206 | 15,623 (5.9%) | ||

| DOT23268 | Fringillidae | Acanthis flammea | Leu: 0.36 | Leu: ROFI06, TRPIP2 | 146,948 | 6,882 (4.7%) |

| DOT23273 | Parulidae | Setophaga striata | Leu: 0.13 | Leu: CNEORN01 | 156,038 | 9,585 (6.1%) |

| DOT23276 | Fringillidae | Acanthis flammea | Leu: 0.32 |

Leu: ACAFLA03, TRPIP2 |

186,877 | 19,653 (10.5%) |

| Para: 4.82 | Para: SISKIN1 | |||||

| DOT23337 | Parulidae | Setophaga petechia | Leu: 0.16 | Leu: CNEORN01, SETPET04 | 179,703 | 8,284 (4.6%) |

| DOT24378 | Vireonidae | Vireo olivaceus | Para: 0.03 | Para: VIOLI06 | 132,855 | 2,793 (2.10%) |

| DOT24402 | Mimidae | Toxostoma rufum | Leu: 1.01 | Leu: DUMCAR04 | 127,161 | 7,773 (6.1%) |

| Plas: TUMIG03, SYAT05 | ||||||

| DOT24420 | Vireonidae | Vireo olivaceus | Para: 0.05 | Para: VIOLI16* | 120,104 | 3,385 (2.8%) |

| DOT24422 | Vireonidae | Vireo olivaceus | Para: 0.50 | Para: VIOLI11 | 138,469 | 8,289 (6.0%) |

| DOT24449 | Cardinalidae | Pheucticus ludovicianus | Leu: 0.002 | Leu: DUMCAR01 | 141,101 | 13,049 (9.2%) |

| Para: 1.29 | Para: PHEMEL02 | |||||

| DOT24451 | Icteridae | Icterus galbula | Leu: 0.34 | Leu: CNEORN01, DUMCAR01 | 168,156 | 16,650 (9.9%) |

| Para: 0.78 | ||||||

| Plas: 0.03 | Para: ICTLEU01, ICTGAL03* | |||||

| DOT24453 | Vireonidae | Vireo olivaceus | Leu: 0.02 | Para: VIOLI11, CHIPAR01 | 176,371 | 17,895 (10.1%) |

| Para: 1.16 | ||||||

| DOT24461 | Mimidae | Dumetella carolinensis | Leu: 0.01 | Leu: DUMCAR01 | 136,987 | 3,674 (2.7%) |

| Para: 0.05 | Para: MAFUS02 | |||||

| MSB:Bird:47757 |

Fringillidae | Loxia curvirostra | Leu: 0.07 | Leu: CB1 | 131,101 | 2,640 (2.0%) |

| MSB:Bird:47825 | Hirundinidae | Tachycineta thalassina | Para: 1.53 | Para: TABI10 | 135,824 | 12,411 (9.1%) |

| MSB:Bird:47846 | Vireonidae | Vireo plumbeus | Para: 0.72 | Para: VIRPLU01, TROAED12 | 173,660 | 29,118 (16.8%) |

| MSB:Bird:47847 | Cardinalidae | Piranga ludoviciana | Para: 1.08 | Para: PIRLUD08*, PIRLUD09* | 133,190 | 9,620 (7.2%) |

| MSB:Bird:48018 | Passerellidae | Spizella passerina | Para: 0.1 | Para: SIAMEX01 | 125,955 | 2,994 (2.4%) |

| MSB:Bird:48026 | Turdidae | Turdus migratorius |

Leu: 0.1 |

Leu: TUMIG09, Unidentified | 166,069 | 10,197 (6.1%) |

| Plas: TROAED24 | ||||||

| MSB:Bird:48045 | Vireonidae | Vireo plumbeus | Para: 1.54 | Para: VIRPLU04, VIRPLU01 | 172,083 | 23,743 (13.8%) |

Blood smears for each sample were examined using light microscopy to screen at least 10,000 red blood cells (RBCs) for the presence and intensity of infection by parasites in the order Haemosporida (Phylum Apicomplexa). We retained 24 samples for transcriptome sequencing that exhibited haemosporidian infection parasitemias (proportion of total RBCs that are infected) of at least 0.02% (two infected cells out of every 10,000 RBCs). The selected samples were examined further by sequencing a cytb barcode locus using the Hellgren et al. (2004) PCR primers to identify the mitochondrial haplotypes of the haemosporidians present in each sample (detailed in Supplementary Methods).

RNA isolation, library preparation, and sequencing

RNA was extracted from blood samples using a hybrid Trizol and Qiagen RNeasy Micro kit protocol. Details of the storage time prior to extraction and the extraction quality for each sample are provided in Dryad Digital Repository Appendix 2, and a step-by-step summary of our RNA extraction protocol is described in the Supplementary Methods. For one sample (DOT23258 from Spizelloides arborea), we sequenced an additional transcriptome using RNA extracted from 1 mg of liver tissue stored in RNALater. The liver tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of Trizol and then input to the same protocol described above.

We quantified RNA using a Qubit fluorometer and assessed RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. We constructed cDNA libraries using the Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA kit and submitted samples to the New York Genome Center for sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2500 machine. Samples were single-indexed and pooled in groups of eight or nine samples per lane, and sequenced to a target depth of 30 million 125 base pair paired-end reads.

Transcriptome assembly and isolation of haemosporidian transcripts

Sequencing reads were quality checked using FastQC (Andrews, 2010). All libraries were assembled de novo using Trinity v2.6.6, implementing quality trimming and adapter removal using the Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) option. We isolated transcripts putatively derived from apicomplexan parasites using the ContamFinder pipeline of Borner et al. (2017). This method uses repeated BLAST searches of contigs from a genome or transcriptome assembly against apicomplexan proteomes from the Eukaryotic Pathogen Database (EuPathDB, Aurrecoechea et al., 2016) and non-apicomplexan proteomes from the UniProt database (Bateman et al., 2017). At each step in this pipeline, only contigs that have their best hit against apicomplexan proteins are retained until only unambiguous parasite-derived contigs remain. To confirm that our pipeline did mistakenly extract host contigs, we also ran ContamFinder on a negative control blood transcriptome (NBCI BioSample: SAMN10247614) from a captive zebra finch (Taenopygia guttata).

We predicted coding regions of haemosporidian transcripts by identifying open reading frames (ORFs) using TransDecoder v3.0.1 (http://transdecoder.github.io), retaining ORFs that were at least 75 amino acids long. We reduced isoform redundancy by selecting only the longest isoform per Trinity gene and using CD-HIT-EST (Fu et al., 2012; parameters -c 0.99, -n 11).

Identification of single-copy haemosporidian orthologs

We used OrthoMCL (Chen et al. 2006; Li et al., 2003) and the PlasmoDB database (Aurrecoechea et al., 2008) to identify single-copy groups of orthologous loci (orthogroups). We assigned transcripts to orthogroups using OrthoMCL and retained only those orthogroups that included a single gene from each of 15 reference Plasmodium species from PlasmoDB. The reference proteomes included multiple members of each subgenus of mammalian Plasmodium (Laverania, Plasmodium, and Vinckeia) as well as two species of avian Plasmodium (Plasmodium gallinaceum and Plasmodium relictum). The genome of the avian haemosporidian Haemoproteus (Parahaemoproteus) tartakovskyi was not used for identifying single-copy orthologs as it has not been as rigorously curated as the Plasmodium genomes that are available on PlasmoDB. We aligned amino acid sequences for each single-copy orthogroup using MAFFT v7.271 (Katoh & Standley, 2013), and obtained the corresponding nucleotide (codon) alignments using PAL2NAL (Suyama et al., 2006). To further reduce the presence of partially assembled isoforms that were retained through this point, we filtered out all contigs that were missing data at > 25% of sites within an alignment. We then performed analyses on two datasets: 1) the complete dataset containing all single-copy orthogroups that we identified with at least one newly sequenced taxon and with reduced missing data (hereafter referred to as “all-orthologs dataset”); and 2) a more conservative subset of the all-orthologs dataset that was restricted to include only orthogroups that were also present as single-copies in Theileria annulata, a member of the outgroup lineage to the haemosporidians (Borner et al., 2016; dataset hereafter referred to as “outgroup-orthologs dataset”).

Prior to analysis, we screened all contigs for index-swapping or ‘bleeding over’ during Illumina sequencing by identifying instances where samples that were sequenced on the same lane were found to have highly similar transcripts within the same orthogroup. If highly similar (<0.1% pairwise divergence) transcripts were recovered from multiple samples that were sequenced on the same lane, we removed these sequences from alignments with the exception of samples that contained the same parasite species as determined through DNA barcoding.

Assigning transcripts to haemosporidian genera

The single-copy ortholog alignments were used to determine the haemosporidian genus of origin for all transcripts from each sample for the purpose of analyzing mixed-species transcriptomes and identifying instances in which a parasite genus was not detected using standard screening approaches. Because missing data can lead to erroneous results in analyses based on sequence similarity (a sequence might show higher similarity to a conserved region of a distantly related sequence than to a highly variable region of a more closely related sequence), we used a quartet resampling strategy to assign transcripts to genera using a custom Ruby script (url: https://sourceforge.net/p/genusassigner/files/). This approach is better suited to deal with incomplete data than a simple blast all-vs-all search because it only compares positions that are present in all sequences. While relatively few nucleotide positions would fulfill this criterion when working with the full alignments, by subsampling only one sequence per genus, we were able to compare a large number of positions without introducing bias due to missing data. For the reference database we used the previously published genomes of P. gallinaceum, P. relictum, and H. (Parahaemoproteus) tartakovskyi (Bensch et al., 2016; Böhme et al., 2018) as well as the previously published transcriptomes of P. ashfordi, P. delichoni, P. homocircumflexum, and L. buteonis (Pauli et al. 2015; Weinberg et al., 2018; Videvall et al., 2017). To increase the diversity of the reference database, particularly for the genera Parahaemoproteus and Leucocytozoon, we added several of the newly sequenced transcriptomes from this study that were determined using microscopy and DNA barcoding to contain a single haemosporidian genus (though in some cases the samples were determined to contain multiple species within that genus). The method proceeded as follows: for each transcriptome contig of unknown origin, one sequence from each of the three reference genera was drawn (Leucocytozoon, Parahaemoproteus, Plasmodium) from the same orthogroup alignment (Fig. 1A). The percentage of sequence identity was then calculated among all four sequences and the same procedure was also performed using the amino acid translation of the sequences. Positions that contained missing data or indels in any of the four sequences were ignored and quartets with less than 150 bp of sequence overlap were discarded (Fig. 1B). If the contig had best hits against different reference sequences in the amino acid and the nucleotide alignments, the quartet was considered ambiguous (Fig. 1C); if both best hits were against the same reference sequence and if at least one hit was a bi-directional best hit, the quartet was counted as a hit for that genus (Fig. 1D). This process was performed for all possible quartet combinations containing one transcriptome contig to be assigned and one reference sequence from each of the three genera. The genus assignment procedure was conducted only for contigs that had sufficient overlap with at least two reference sequences from each haemosporidian genus. Contigs that had best hits against a single genus in the majority of quartets (> 50%) were assigned to that genus, while contigs with ambiguous best hits or insufficient overlap to the reference sequences were discarded.

Figure 1.

Genus assignment based on a quartet resampling strategy. (A) For each transcriptome contig of unknown origin (green), one reference sequence from each genus (Plasmodium: orange, Parahaemoproteus: purple, Leucocytozoon: blue) is drawn from the same orthogroup alignment. (B) Sequence quartets with less than 150 bp of overlap among all four sequences are discarded. (C) If the contig has best hits (arrows) against different reference sequences in the amino acid and the nucleotide alignments, the quartet is considered ambiguous and no genus assignment is made. (D) If the nucleotide and the amino acid data result in a best hit against the same reference sequence and if at least one best hit is bi-directional (double headed arrow), the quartet is counted as positive for that genus. This procedure is executed for all possible quartet combinations within an orthogroup. Contigs with unambiguous hits against the same genus in the majority of quartets are assigned to that genus. Genus assignment was only conducted using orthogroup alignments with a minimum of two sequences for each reference genus.

To ensure that none of the samples employed as reference transcriptomes contained more than one parasite genus, each of the newly sequenced transcriptomes in the reference database were individually moved from the ‘reference’ pool to the ‘test’ pool. In total, eight transcriptomes were found to contain exclusively sequences that were assigned to the genus Parahaemoproteus and five transcriptomes only comprised sequences that were assigned to the genus Leucocytozoon. These 13 transcriptomes were combined with the previously published genomes/transcriptomes to form the final reference database, which was used to assign the contigs from the remaining transcriptome samples that were determined to contain mixed-genus infections.

Quantifying the number of infections per sample

The number of haemosporidian contigs detected within a single orthogroup for each sample can potentially exceed the number expected from microscopy and DNA barcoding for several reasons. First, a sample might contain additional parasite species that we did not detect using standard methods due to either: 1) cryptic mtDNA barcode sequences and morphology among multiple parasite species that have divergent nuclear genomes; or 2) the presence of low-intensity infections that were not detected due to limitations of the standard methods. Alternatively, a sample could appear to contain additional parasite species due only to bioinformatic error. Sources of bioinformatic error include: 1) the assignment of a contig to an incorrect genus (resulting in the appearance of multiple parasite genera within a sample when there is just one); or 2) the accidental retention of multiple isoforms of the same gene from the same parasite (resulting in the appearance of more species from the same genus than expected). Following the genus assignment procedure, our goal was to determine whether the number of distinct infections that we detected in each transcriptome matched the number that were identified by microscopy and DNA barcoding, and if not, establish whether this variation could be attributed to one of the causes listed above. For this analysis we classified sequences as isoform variants if they differed exclusively at the beginning/end of the contig or only by the presence/absence of gaps.

To quantify the number of infections per sample, we identified all orthogroups for which the number of haemosporidian contigs from at least one sample exceeded the number expected from microscopy or DNA barcoding (i.e. we flagged an orthogroup if we expected to find at most N transcripts from a given sample, but > N transcripts from that sample were present in the orthogroup alignment). To investigate whether the ‘excess’ sequences represented distinct infections or bioinformatic error, we used an approach that combined sequence identity (to determine whether a sequence was an isoform variant) and phylogeny (to determine whether a sequence was assigned to the correct genus). We classified an excess sequence as bioinformatic error if: 1) multiple sequences appeared to be isoform variants of the same gene from the same species, or 2) the sequence was found to be nested within a clade containing reference sequences from a different genus, indicating an incorrect genus assignment. In contrast, we classified an excess sequence as a true infection that was missed by the standard methods if: 1) no sequences from the same sample were isoform variants; and 2) all sequences from the same sample were phylogenetically associated with reference samples from the same genus. To determine the phylogenetic positions of each contig, we generated gene trees for each orthogroup alignment using RAxML v8.2.4 (Stamatakis, 2014) implementing the GTRGAMMA model of substitution and 100 rapid bootstraps.

As an alternative method for identifying the number of infections per sample, we searched transcriptomes for contigs from the cytb gene to determine whether we could detect cytb barcode sequences that were different from those that we generated using Sanger sequencing. First, we used BLASTN with liberal search parameters (E-value = 10) to search each transcriptome assembly against a database of all complete avian haemosporidian cytb sequences that are available on GenBank. We then used RSEM (Li and Dewey 2011) to generate TPM (transcripts per million) values for cytb contigs based on both the total assembly and just the haemosporidian component of each transcriptome.

Identifying variation in gene content among metatranscriptomes

We sought to characterize differences in the sets of protein-coding genes that we were able to assemble among metatranscriptomes to determine whether samples with different parasite species compositions and infection intensities yielded similar datasets for downstream analysis. To do so we used a presence/absence matrix of all samples and all single-copy ortholog groups from the all-orthologs dataset (1 if a contig was present for an ortholog in a given sample, 0 if not) as input for a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) in the R package FactoMineR (Lê et al., 2008) using the function “MCA”. MCA is similar to principal component analysis, but is used for categorical variables including presence/absence data.

Statistical analyses

An additional goal was to understand the factors that influenced the number of haemosporidian loci that we were able to assemble for each sample. We used multiple regression models to determine what factors best explained the number of haemosporidian transcripts that were retained per metatranscriptome sample (dependent variable), using either the all-orthologs dataset or a less restrictive dataset containing the total number of transcripts from all single-copy orthogroups regardless of data completion. We tested the following predictor variables in each model: parasitemia (percentage of RBCs infected with haemosporidians), the total number of reads for each sample, and the number of haemosporidian infections detected in each sample (estimated from the number of distinct infections found in metatranscriptomes). We built a set of candidate models that included all additive combinations of the predictor variables and used the R package MuMIn (Bartoń, 2019) to conduct multimodel inference with Akaike’s Information Criterion for small sample sizes (AICc) and calculate Akaike weights (ω) to evaluate support and rank models. All models within 2 ΔAICc of the highest-ranked model were considered equivalent, and we used these to calculate model averages and 95% confidence limits. All models were assessed to confirm that there was no collinearity among predictor variables and that residuals were normally distributed with homogenous variance.

Results

Haemosporidian transcriptome summary

We sequenced 24 blood transcriptomes from 16 host species representing ten avian families (Table 1). Using microscopy, we determined that each sample contained one to three haemosporidian genera (total parasitemia range: 0.02–5.1%; Dryad Digital Repository Appendix 1). Across samples, we identified 33 haemosporidian cytb lineages using DNA barcoding, representing a broad phylogenetic diversity of the genera Leucocytozoon, Parahaemoproteus, and Plasmodium (Fig. 2). The number of haemosporidian cytb haplotypes that we identified in each sample from DNA barcoding ranged from one to four (Table 1). We obtained an average of 40 million paired-end reads per sample (range: 13 to 86 million), that yielded an average of 152,842 assembled transcripts per sample (Table 1; range: 106,598 to 264,206). ContamFinder (Borner et al., 2017) identified between 2,640 and 29,118 haemosporidian transcripts per sample (between 2% and 16.8% of the total number of transcripts; Table 1). We sequenced separate transcriptomes from blood and liver for one sample (DOT23258 from the host Spizelloides arborea), and found that the blood transcriptome yielded a much higher proportion of parasite transcripts (7.9% from blood versus 2.5% from liver). The negative control sample from a lab-reared zebra finch yielded zero parasite contigs as expected, demonstrating that our approach is robust to false positives.

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic diversity of haemosporidian parasites detected in host samples selected for transcriptome sequencing. Shown are cytb phylogenies for the genera (A) Leucocytozoon, (B) Parahaemoproteus, and (C) Plasmodium, generated from all cytb haplotypes available on the avian haemosporidian database MalAvi as of April 2019 (Bensch et al. 2009). Depicted on each phylogeny are the names of the cytb lineages (determined by cytb barcoding) that were included for metatranscriptome sequencing or were used as references. Names in red indicate lineages that were used as references for the genus assignment procedure that were obtained from previously published research, and names in blue indicate lineages that were included in the reference database and were sequenced for this study. Names in black represent lineages that were sequenced in this study and were found in mixed-genus samples, and so were used as input for genus assignment.

Identification of single-copy ortholog groups with OrthoMCL yielded 3,470 orthogroups with at least one contig from a sample included in this study. The ‘all-orthologs’ dataset, with all sequences having less than 25% missing data, consisted of 1,502 orthogroups. The more conservative ‘outgroup-orthologs’ dataset consisted of 879 orthogroups that were confirmed to also be single-copy in the haemosporidian outgroup Theileria annulata. Prior to analysis we removed 27 contigs across 15 different orthogroups (Dryad Digital Repository Appendix 3) that we determined were likely to represent cross-contamination from different samples that were sequenced on the same lane, as evidenced by low coverage of putative contaminants (<0.5 transcripts per million) relative to highly similar sequences with high coverage (>100 transcripts per million.

Assigning transcripts to haemosporidian genera

Out of the 1,502 alignments in the all-orthologs dataset, 694 contained at least two reference sequences from each of the genera Leucocytozoon, Parahaemoproteus, and Plasmodium and so were able to be used for computational genus assignment (478 of 879 alignments in the outgroup-orthologs dataset). Out of 7,103 contigs of unknown origin, 98% were able to be unambiguously assigned to a genus. The genus assignment procedure found that two samples in both datasets (all-orthologs and outgroup-orthologs) contained at least one transcript that was assigned to a haemosporidian genus that was not detected using microscopy or DNA barcoding (hereafter referred to as an ‘undetected’ genus). Using the all-orthologs dataset, we found a total of 27 contigs that were assigned to an undetected genus (Supplementary Table 1), 26 of which were contigs that were assigned to the genus Plasmodium for a single sample (DOT24420 from Vireo olivaceus). Using the outgroup-orthologs dataset we found that 21 of these contigs were retained (Supplementary Table 1). We tested whether each of these contigs that were assigned to an undetected genus was recovered as monophyletic with respect to all other sequences that were assigned to that genus (including both references and sequences that were computationally assigned to genera) to identify contigs that were likely to have been incorrectly assigned. We found that one contig from a Turdus migratorius sampled in Alaska (DOT23244), which was assigned to the undetected genus Plasmodium, was likely derived from Leucocytozoon based on its position with respect to other Leucocytozoon sequences within the orthogroup gene tree. In contrast, the 26 contigs that were assigned to the undetected genus Plasmodium for the V. olivaceus sample DOT24420 shared an exclusive common ancestor with other Plasmodium sequences. As a result we classified DOT24420 as containing a true Plasmodium infection that was not detected by DNA barcoding or microscopy.

Infection quantification

In addition to identifying haemosporidian infections from genera that were missed by DNA barcoding and microscopy, we also sought to determine whether any samples contained more infections by distinct lineages within a given genus than we were able to detect using standard methods. We used the all-orthologs and outgroup-orthologs datasets to quantify the number of haemosporidian infections per sample. We found that in 13 samples the maximum number of contigs for at least one genus exceeded the number expected from the DNA barcode result (Table 2). The outgroup-orthologs dataset identified the same number of additional infections as the all-orthologs dataset, and so we report the results from the all-orthologs dataset below. For each orthogroup for which we recovered more transcripts for a sample than expected, we manually inspected the gene trees and sequence alignments to evaluate whether these sequences were isoform variants or represented distinct infections. This procedure identified 11 contigs across six samples that appeared to be retained isoform variants that only differed at the beginning or end of the contigs or by insertions/deletions within the sequence. These contigs were ignored for further infection quantification. We identified six additional instances across five samples where there was evidence from multiple orthogroups for more infections than expected based on DNA barcoding. In two of these instances (Leucocytozoon in DOT23244 and Leucocytozoon in MSB:Bird:48026), the sample was found to contain two additional infections from the same genus that were not detected by DNA barcoding (e.g. three infections were detected when only one was expected). In two other instances, additional infections were only supported by a single orthogroup for a sample (Table 1), though these excess infections were supported by two and six orthogroups, respectively, when we relaxed the all-orthologs dataset to include contigs with up to 50% missing data (Supplementary Table 2). We found evidence for additional infections from all three haemosporidian genera, though this phenomenon was observed most often for Leucocytozoon (seven additional infections detected). The infection quantification procedure identified between one and six distinct haemosporidian infections per sample (Dryad Digital Repository Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Samples for which at least one orthogroup contained more contigs from a given haemosporidian genus than expected based on the results of microscopy or DNA barcoding. Results from the all-orthologs dataset. Shown are the maximum number of contigs that were expected for a given genus for any orthogroup within a sample, the maximum number that were observed in any orthogroup, the number of observed orthogroups in which that number was exceeded, and the number of orthogroups that were found to have an excess number of distinct sequences after manual inspection of gene trees and alignments. Samples in bold indicate that the presence of additional infections was confirmed by manual inspection, in which case the final estimate for the number of infections reflects the maximum number of contigs observed for a given sample/genus. An asterisk next to the final estimate of infection number indicates that excess infections were supported by just a single orthogroup using the all-orthologs dataset, but were supported by more than one orthogroup using a dataset that allowed up to 50% missing data.

| Sample | Genus | Max contigs expected | Max contigs observed | Number orthogroups that exceeded expected contig number | Number orthogroups that passed manual inspection | Final estimate of number of infections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOT23227 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| DOT23232 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| DOT23244 | Leucocytozoon | 1 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 3 |

| DOT23258 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| DOT23273 | Leucocytozoon | 1 | 2 | 171 | 170 | 2 |

| DOT23276 | Leucocytozoon | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| DOT23276 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| DOT24422 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| DOT24451 | Plasmodium | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| MSB:Bird:47757 | Leucocytozoon | 1 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| MSB:Bird:47825 | Parahaemoproteus | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| MSB:Bird:47846 | Parahaemoproteus | 2 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 3 |

| MSB:Bird:48026 | Leucocytozoon | 2 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 4 |

| MSB:Bird:48026 | Plasmodium | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2* |

| MSB:Bird:48045 | Parahaemoproteus | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3* |

We also searched for contigs that were significant BLAST hits to cytb, as we sought to determine whether we could compare cytb sequences found using metatranscriptomics to those found using DNA barcoding. This search revealed cytb contigs in 15 of 24 transcriptomes (Supplementary Table 4), with samples having parasitemias below ~0.5% tending not to recover any cytb contigs. Several transcriptomes contained multiple cytb contigs, and we recovered 35 cytb contigs in total. All 35 contigs were confirmed as haemosporidian cytb following a separate BLAST search against the non-redundant nucleotide database. Out of the 35 cytb contigs, 12 did not overlap with the DNA barcode fragment that we sequenced and so could not be directly compared to the barcode results. The remaining 23 contigs largely matched one of the cytb barcodes that was generated for that sample using Sanger sequencing, though in several instances we recovered a contig that differed by one to three bases from a previously identified barcode (Supplementary Table 4). In the 15 transcriptomes in which we recovered cytb contigs, we consistently found low transcripts per million (TPM) values for these contigs (Supplementary Table 4), indicating low expression of cytb in these samples. Overall, the relationship between parasitemia and TPM values was positive (Spearman’s rho=0.78, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figure 2). We conducted the same analysis on two previously published transcriptomes of natural avian haemosporidian infections (Haemoproteus columbae, Field et al., 2018; Leucocytozoon buteonis, Pauli et al., 2015), and found similarly low cytb TPM values for L. buteonis though H. columbae yielded higher values than any of the novel transcriptomes sequenced for this study (Supplementary Table 4).

Identifying variation in gene content among metatranscriptomes

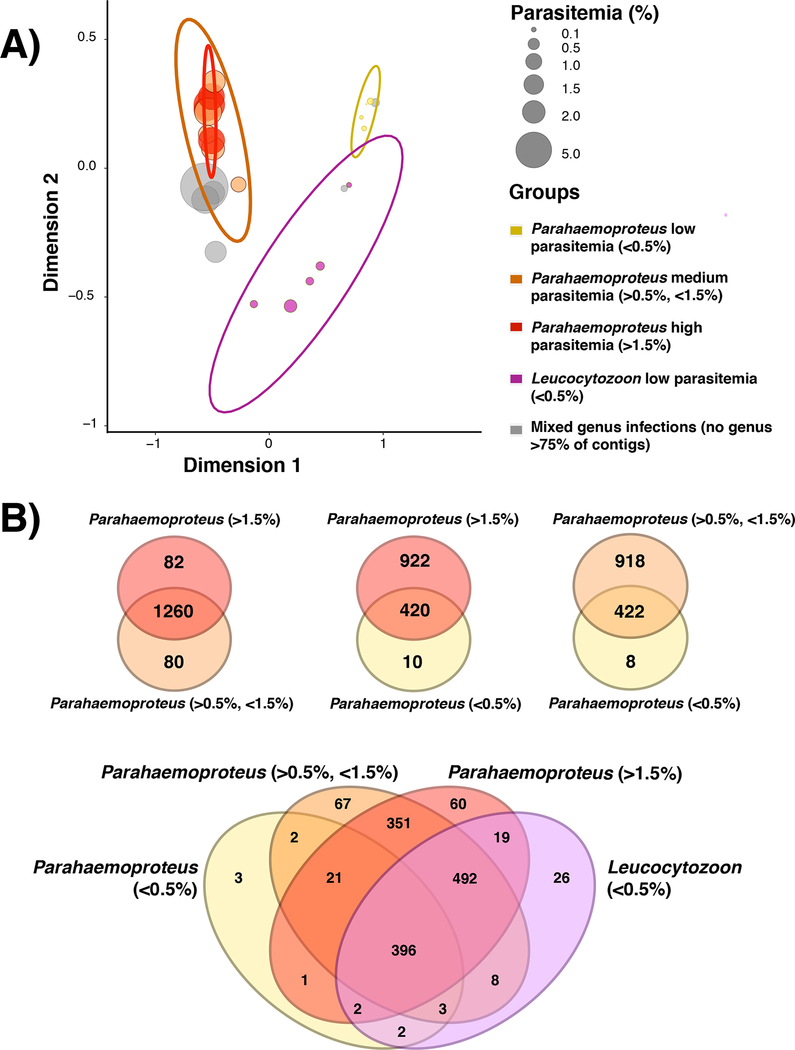

Multiple correspondence analysis of gene presence/absence within the all-orthologs dataset revealed separation of the samples into clusters based on the parasite genera present in the sample and the intensity of the infections (Fig. 3A). The first dimension of the MCA appeared to separate samples based on their infection intensity, as samples with Parahaemoproteus infections of greater than 0.5% parasitemia clustered together to the exclusion of samples with Parahaemoproteus or Leucocytozoon infections of less than 0.5% intensity. The second dimension appeared to separate samples based on the genus of the parasites within the infection. Samples containing only parasites in the genus Leucocytozoon were found to cluster to the exclusion of the remaining samples with Parahaemoproteus-only or mixed-genus infections, suggesting that different haemosporidian genera are likely to produce somewhat different subsets of the total orthogroup pool that we recovered across all samples regardless of infection intensity. The results of the MCA were supported by analysis of the overlap of the orthogroups found in different clusters that were defined by taxonomic composition and parasitemia (Fig. 3B). This analysis showed that samples with parasitemias below 0.5% generally produced a subset of the orthogroups that were recovered from samples with higher parasitemias.

Figure 3.

Samples that contained different parasite genera and infection intensities differed in the composition of the orthogroups for which data was generated. A) Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) showing that samples with Parahaemoproteus infections of >0.5% parasitemia cluster together to the exclusion of samples with low-intensity (<0.5%) Parahaemoproteus or Leucocytozoon infections. B) Venn diagrams demonstrating overlap in the number of orthogroups for which data was generated for sample groups defined by parasite genus and infection intensity.

Statistical analyses

We found that a full model retaining parasitemia, the number of haemosporidian infections that were inferred from transcriptomes, and the number of reads best explained the number of haemosporidian transcripts isolated per sample (Table 3). This was true for both the total number of transcripts that were found across all single-copy orthogroups, as well as the number of transcripts retained within the all-orthologs dataset containing only contigs with less than 25% missing data (Fig. 4, Table 3). Using either dataset, the best model was not well differentiated from models that contained a subset of the predictor variables. All predictor variables in the full model had positive coefficients (Supplementary Table 3), indicating a positive relationship with the number of haemosporidian transcripts, though parasitemia was the only predictor for which the 95% confidence limit did not overlap zero in either model.

Table 3.

Results of multiple regression models explaining number of haemosporidian loci obtained per transcriptome. The number of distinct haemosporidian infections, parasitemia, and number of reads are included as explanatory variables. Parasitemia values were log transformed prior to analysis. Model weights are > 0.01. Models in bold indicate delta AICc values < 2.0. ‘Number of infections’ refers to the results from the transcriptomes and includes infections that were not detected using DNA barcoding and microscopy.

| Dependent variable | Model | df | Log Likelihood | AICc | Delta AICc | Weight (Wi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of single-copy orthologs | ||||||

| Number of infections + Parasitemia + Number of reads | 5 | −203.54 | 420.4 | 0.00 | 0.542 | |

| Number of infections + Parasitemia | 4 | −205.44 | 421.0 | 0.58 | 0.405 | |

| Parasitemia | 3 | −209.44 | 426.1 | 5.68 | 0.032 | |

| Parasitemia + Number of reads | 3 | −208.42 | 426.9 | 6.54 | 0.021 | |

| Intercept | 2 | −217.15 | 438.9 | 18.45 | 0.000 | |

| Number of orthologs in ‘all-orthologs’ dataset | ||||||

| Number of infections + Parasitemia + Number of reads | 5 | −157.41 | 328.2 | 0.00 | 0.316 | |

| Number of infections + Parasitemia | 4 | −159.10 | 328.3 | 0.15 | 0.293 | |

| Parasitemia | 3 | −160.85 | 328.9 | 0.73 | 0.219 | |

| Parasitemia + Number of reads | 3 | −159.63 | 329.4 | 1.21 | 0.172 | |

| Intercept | 2 | −179.75 | 364.1 | 35.9 | 0.000 |

Figure 4.

Relationship between parasitemia and number of haemosporidian transcripts. Samples that generated a higher number of haemosporidian transcripts tended to have more intense infections, contain infections from a greater number of parasite species, and had higher sequencing depth. The number of haemosporidian transcripts shown here refers to the number of transcripts for each sample in the ‘all-orthologs’ dataset.

Discussion

Blood parasites of wildlife are abundant, widespread, and ecologically important for vertebrates worldwide, yet molecular studies of many of these taxa have continued to rely largely on DNA barcoding surveys even as high-throughput sequencing technology has advanced. Efforts to sequence the genomes of haemosporidians that infect wildlife have been hindered by the often low intensities of naturally-occurring infections, the presence of multiple parasite species within a single sample, and large amounts of host DNA within samples, resulting in a general lack of genomic resources for the overwhelming diversity of haemosporidians. However, we show here that sequencing the blood transcriptomes of hosts with multi-species, low-intensity parasite infections can yield large quantities of genome-wide sequence data at a scale that is not currently available for the overwhelming majority of haemosporidian species. Host metatranscriptomes detected a significant number of infections that were not observed using microscopy or DNA barcoding, illustrating that associations among birds and their haemosporidian parasites are likely more complex than previously estimated. This further highlights the potential of high-throughput sequencing to provide a more precise view of host-parasite interactions than conventional approaches.

Vertebrate transcriptomes are valuable sources of parasite genomic data

Though genome sequencing approaches have proven unfeasible for most wildlife haemosporidians, we found that sequencing the blood transcriptomes of birds, even those with very low infection intensities, yielded a large proportion of the protein-coding gene repertoire for haemosporidians in the genera Leucocytozoon, Parahaemoproteus, and Plasmodium. For single-infection samples with parasitemias as low as 0.027% (reflecting approximately three parasites for every 10,000 host red blood cells), we obtained data from at least 1,300 single-copy genes (Table 4). In total we identified 3,470 genes that appear to be single-copy across all malaria parasites, showing that even the samples with the lowest infection intensities yielded a significant proportion of the conserved haemosporidian protein-coding genome. This finding has important implications for future research because low-parasitemia infections similar to those sequenced in this study are common in bird populations (Valkiūnas, 2004), suggesting that the sequencing of avian blood transcriptomes is a promising approach to generate large quantities of genetic data from across the genome of many poorly-studied blood parasite species.

Table 4.

Transcriptome sequencing results for samples that contained an infection by a single haemosporidian species. Shown are the number of reads sequenced per sample, the parasitemia for each sample (percentage of host red blood cells that were infected by haemosporidians), the number of single-copy orthologs for which we obtained data for each sample, and the number of single-copy orthologs for which we obtained data with minimal (<25%) missing data.

| Sample | MalAvi cytb haplotype | Number of reads | Parasitemia (%) | Number single-copy orthologs | Number orthologs in ‘all orthologs’ dataset (<25% missing data) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOT24378 | VIOLI06 | 34,867,737 | 0.027 | 1,300 | 211 |

| MSB:Bird:48018 | SIAMEX01 | 37,191,077 | 0.100 | 1,311 | 190 |

| DOT24422 | VIOLI11 | 34,358,594 | 0.500 | 2,920 | 885 |

| MSB:Bird:47825 | TABI10 | 39,479,381 | 1.53 | 3,013 | 1,028 |

| DOT23232 | SISKIN1 | 39,508,809 | 1.654 | 2,955 | 1,029 |

We found that the number of haemosporidian transcripts that were assembled per sample was dependent primarily on the intensity of the infection. Sequencing depth had a comparatively weak impact on the number of assembled parasite contigs, as illustrated by the observation that samples with higher parasitemias generally produced more haemosporidian contigs than similar samples with higher total read depth (e.g. sample DOT23244 with parasitemia of 0.15% and 13.2 million reads produced more parasite contigs than sample DOT24461 with parasitemia of 0.06% and 40.3 million reads). Our results indicate that large quantities of haemosporidian sequence data can be obtained with as few as 10 million paired-end reads using samples with at least 0.1% parasitemia, though it appears that the number of complete protein-coding genes increases substantially between approximately 0.1 and 0.5% parasitemia (Table 4), with samples having at least ~1% parasitemia being the most likely to produce over 1,000 largely complete protein-coding genes. These results were supported by the MCA that showed that samples with low parasitemias (<0.5%) tended to recover subsets of the loci that were generated by samples with parasitemias above 0.5%. The importance of infection intensity for the success of parasite transcriptome sequencing as well as other next-generation sequencing approaches such as DNA sequence capture (Barrow et al., 2018) speaks to the value of quantifying parasite infections using either microscopy or qPCR in addition to the standard approach of recording presence/absence through molecular screening techniques. Future metatranscriptomic research on haemosporidians and other symbionts should seek to identify the frequency of chimeric sequences, though in practice this will be difficult until comprehensive reference databases from single-infection samples are available.

Blood transcriptomes reveal infections missed by standard methods

Our computational estimates of within-host haemosporidian species richness revealed an unexpectedly high number of infections that were not detected by standard microscopic or DNA barcoding approaches. In total, we discovered evidence for 11 infections from the 24 host blood transcriptomes that were not detected by a standard microscopic screening protocol or by sequencing a widely used cytb barcode fragment: one infection was from a genus that was not detected at all using the standard methods, while the other 10 were additional infections from a genus that was recorded using standard methods, but the number of infections was underestimated. The discovery of these infections increased the total number of infections detected in our sample by 23% (~0.46 infections per host), representing a substantial increase in our estimate of parasite abundance among the sampled hosts. These additional infections were supported by multiple orthogroups and were discovered after screening transcripts for possible cross-contamination, and so we are confident that these findings reflect real host-parasite associations. Though alternative explanations for the detection of excess infections such as lineage-specific gene-duplication are possible, the fact that we also found them in the outgroup-orthologs dataset that consisted solely of orthogroups that are also single-copy in the outgroup Theileria suggests that these sequences most likely represent true infections that were missed by standard methods.

The failure of conventional methods to detect ~23% of haemosporidian infections was possibly due to a combination of barcode primer bias (Zehtindjiev et al., 2012) and differential infection intensities among the co-infecting parasites (Martinez et al. 2009; Valkiūnas et al., 2006). For example, the parasites that we detected only in the transcriptomes were represented in a small minority of the transcripts that we analyzed, likely reflecting low parasitemias. Our finding that cytb barcoding underestimates the number of low-intensity haemosporidian infections has important implications for our understanding of parasite interactions within individual hosts, as well as the disease burden that birds face. Many bird species have relatively long lifespans (The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database; Tacutu et al., 2018), and so it should come as no surprise that long-lived species tend to acquire numerous distinct parasite infections over their lifetimes. For example, the transcriptome that we sequenced from a Baltimore oriole (Icterus galbula), which has been documented to live as long as 14 years, had six distinct haemosporidian infections (Supplementary Fig. 1) – two Leucocytozoon, two Parahaemoproteus, and two Plasmodium – an infracommunity complexity that has not been previously documented for haemosporidians. The possibility that older hosts acquire more diverse infracommunities has been poorly explored (Lo et al., 1998; Gutiérrez et al., 2019), and should be a focus of future research as it has become clear that standard DNA barcoding approaches may have limited our ability to understand parasite infection dynamics in long-lived species.

Linking metatranscriptomics and DNA barcoding

We found that metatranscriptomes do not reliably recover the cytb barcode fragment that is commonly used to study haemosporidians due to the low expression level of this gene in host blood. The low expression of cytb is surprising considering that haemosporidians are thought to have dozens of copies of the mitochondrial genome per cell (Joseph et al. 1989), though this pattern seems to be supported broadly by our finding of similarly low cytb expression in the previously published transcriptomes of the avian malaria parasites Leucocytozoon buteonis and Haemoproteus columbae (Pauli et al., 2015; Field et al., 2018). The inconsistent recovery of cytb therefore makes it difficult to link sequences from complex metatranscriptomes with the larger body of avian haemosporidian research that is based on cytb barcodes, as we found that standard barcoding using Sanger sequencing routinely missed infections. Though we found that it is possible to associate contigs of unknown origin with cytb barcodes using our genus assignment procedure, it is not always possible particularly when an infection consists of multiple parasite species from the same genus. However, the link between metatranscriptomics and DNA barcoding is likely to improve in the near future with the advent of: 1) the application of increasingly sensitive metabarcoding approaches that are consistently able to characterize all parasites within a single host, and 2) the growth of haemosporidian genomic resources that will allow the assignment of transcripts of unknown origin to specific haemosporidian lineages. Ultimately, an integration of metatranscriptomics and metabarcoding will maximize our understanding of haemosporidian diversity and will have the potential to address the currently poorly understood connection between mitochondrial and nuclear genetic diversity across haemosporidians.

Conclusions

The study presented here illustrates the potential to use RNA-Seq metatranscriptomics in a targeted manner to generate genomic resources for specific blood parasite species, though it also demonstrates the importance of considering the potential presence of parasites and other symbionts in transcriptome assemblies that are generated for the purpose of studying the host. Our results suggest that care should be taken to screen host tissue samples for parasites before transcriptome sequencing, though if this is not possible, we recommend using a bioinformatic filtering process such as the ContamFinder (Borner et al., 2017) pipeline. ContamFinder and similar pipelines can be adapted to identify transcripts that are derived from any symbiont group of interest as long as sufficient reference data exists. We anticipate that the diverse parasite genomic resources presented here will not only be a boon to haemosporidian research, but will aid future researchers seeking to identify non-target contigs within their vertebrate genome and transcriptome assemblies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Capainolo, Andy Johnson, Chauncey Gadek, Daniele Wiley, Jade McLaughlin, Andrea Chavez, Jeff Groth, and Paul Sweet for assistance with collecting, screening, and curating samples. We thank NIH award 1R03AI117223-01A1,

NSF-PRFB 1811806, the Society of Systematic Biologists, Explorer’s Club, the American Museum of Natural History Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Grant, the Federal Bureau of Land Management Rio Puerco Field Office, New Mexico Ornithological Society, and the Richard Gilder Graduate School for funding. Voucher specimens for each sampled host were collected under U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permits MB779035–1 and MB-726595–0, State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game Scientific permits 16–013 and 17–092, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation permit 1480, and New Mexico Department of Game and Fish permit No. 3217. Sampling protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the American Museum of Natural History and the University of New Mexico.

Footnotes

Data accessibility

Vouchered specimen information is available from the Arctos database (arctosdb.org) and the American Museum of Natural History (http://sci-web001.amnh.org/db/emuwebamnh/index.php). Raw read data has been uploaded to NCBI SRA (accession PRJNA529266). DNA barcode (cytb) sequences have been deposited in GenBank (accession MK783143– MK783187) and the MalAvi database (http://mbio-serv2.mbioekol.lu.se/Malavi/). All ContamFinder output, sequence alignments from the ‘all-ortholog’ dataset, and appendices have been archived in a Dryad digital repository: https://doi.org/doi:10.5061/dryad.2646vp0 (Galen et al. 2019).

References

- Alexander H, Jenkins BD, Rynearson TA, & Dyhrman ST (2015). Metatranscriptome analyses indicate resource partitioning between diatoms in the field. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 112(17), E2182–E2190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421993112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S (2010). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

- Asghar M, Hasselquist D, Hansson B, Zehtindjiev P, Westerdahl H, & Bensch S (2015). Hidden costs of infection: chronic malaria accelerates telomere degradation and senescence in wild birds. Science, 347(6220), 436–438. doi: 10.1126/science.1261121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea C, Barreto A, Basenko EY, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Cade S, … Zheng J (2016). EuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen genomics database resource. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D581–D591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, … Wang H (2008). PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(suppl_1), D539–D543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow LN, Allen JM, Huang X, Bensch S, & Witt CC (2018). Genomic sequence capture of haemosporidian parasites: Methods and prospects for enhanced study of host-parasite evolution. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(2), 400–410. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoń K (2019). MuMin: multi-model inference. R Package, version 1.42.1. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn

- Bateman A, Martin MJ, O’Donovan C, Magrane M, Alpi E, Antunes R, … Zhang J (2017). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S, Canbäck B, DeBarry JD, Johansson T, Hellgren O, Kissinger JC, … Valkiūnas G (2016). The Genome of Haemoproteus tartakovskyi and Its Relationship to Human Malaria Parasites. Genome Biology and Evolution, 8(5), 1361–1373. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S, Hellgren O, & Pérez‐Tris J (2009). MalAvi: a public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Molecular Ecology Resources, 9(5), 1353–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme U, Otto TD, Cotton JA, Steinbiss S, Sanders M, Oyola SO, … Berriman M (2018). Complete avian malaria parasite genomes reveal features associated with lineage-specific evolution in birds and mammals. Genome Research, 28(4), 547–560. doi: 10.1101/gr.218123.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, & Usadel B (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 30(15), 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner J, & Burmester T (2017). Parasite infection of public databases: a data mining approach to identify apicomplexan contaminations in animal genome and transcriptome assemblies. BMC Genomics, 18, 100. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3504-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner J, Pick C, Thiede J, Kolawole OM, Kingsley MT, Schulze J, … Burmester T (2016). Phylogeny of haemosporidian blood parasites revealed by a multi-gene approach. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 94, 221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Mackey AJ, Stoeckert CJ Jr., & Roos DS (2006). OrthoMCL-DB: querying a comprehensive multi-species collection of orthologs groups. Nucleic Acids Research, 34, D363–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham F, Achuthan P, Akanni W, Allen J, Amode MR, Armean IM, … Flicek P (2018). Ensembl 2019. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(D1), D745–D751. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field JT, Weinberg J, Bensch S, Matta NE, Valkiūnas G, & Sehgal RNM (2018). Delineation of the genera Haemoproteus and Plasmodium using RNA-Seq and multi-gene phylogenetics. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 86(9), 646–654. doi: 10.1007/s00239-018-9875-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, & Li W (2012). CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 28(13), 3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen SC, Borner J, Martinsen ES, Schaer J, Austin CC, West CJ, & Perkins SL (2018a). The polyphyly of Plasmodium: comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of the malaria parasites (order Haemosporida) reveal widespread taxonomic conflict. Royal Society Open Science, 5(5), 171780. doi: 10.1098/rsos.171780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen SC, Nunes R, Sweet PR, & Perkins SL (2018b). Integrating coalescent species delimitation with analysis of host specificity reveals extensive cryptic diversity despite minimal mitochondrial divergence in the malaria parasite genus Leucocytozoon. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 18:128. doi: 10.1186/s12862-018-1242-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen SC, Borner J, Williamson JL, Witt CC, & Perkins SL (2019). Data from: Metatranscriptomics yields new genomic resources and sensitive detection of infections for diverse blood parasites. Dryad Digital Repository. 10.5061/dryad.2646vp0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez JS, Piersma T, & Thieltges DW (2019). Micro- and macroparasite species richness in birds: The role of host life history and ecology. Journal of Animal Ecology, 88(8), 1226–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren O, Waldenström J, & Bensch S (2004). A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. Journal of Parasitology, 90(4), 797–802. doi: 10.1645/GE-184R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren O, Atkinson CT, Bensch S, Albayrak T, Dimitrov D, Ewen JG, … and Marzal A (2015). Global phylogeography of the avian malaria pathogen Plasmodium relictum based on MSP1 allelic diversity. Ecography, 38(8), 842–850. [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Hansson R, Palinauskas V, Valkiūnas G, Hellgren O, & Bensch S (2018). The success of sequence capture in relation to phylogenetic distance from a reference genome: a case study of avian haemosporidian parasites. International Journal for Parasitology, 48(12), 947–954. doi: 10.1016/j.ipara.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JT, Aldritt SM, Unnasch T, Puijalon O, & Wirth DF (1989). Characterization of a conserved extrachromosomal element isolated from the avian malarial parasite Plasmodium gallinaceum. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 9(9), 3621–3629. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, & Standley DM (2013). MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(4), 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepfli K-P, Paten B, the Genome 10K Community of Scientists, & O’Brien SJ (2015). The genome 10K project: A way forward. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 3, 57–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-090414-014900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachish S, Knowles SCL, Alves R, Wood MJ, & Sheldon BC (2011). Fitness effects of endemic malaria infections in a wild bird population: the importance of ecological structure. Journal of Animal Ecology, 80, 1196–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, & Salzberg S (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods, 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BB, Miller EC, Rhodes MK, & Wiens JJ (2017). Inordinate fondness multiplied and redistributed: the number of species on earth and the new pie of life. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 92(3), 229–265. doi: 10.1086/693564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lê S, Josse J, & Husson F (2008). “FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis”. Journal of Statistical Software, 25 (1). doi: 10.18637/jss.v025.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, & Dewey CN (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics, 12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr., & Roos DS (2003). OrthoMCL: Identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Research, 13, 2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CM, Morand S, & Galzin R (1998). Parasite diversity/host age and size relationship in three coral-reed fishes from French Polynesia. International Journal for Parasitology, 28(11), 1695–1708. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes RJ, Mérida AM, & Cerneiro M (2017). Unleashing the potential of public genomic resources to find parasite genetic data. Trends in Parasitology, 33(10), 750–753. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Martinez-de la Puente J, Herrero J, & del Cerro S (2009). A restriction site to differentiate Plasmodium and Haemoproteus infections in birds: on the inefficiency of general primers for detection of mixed infections. Parasitology, 136, 713–722. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009006118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DA (2009). Evolution of the Apicomplexa: where are we now? Trends in Parasitology, 25(8), 375–382. doi:1016/j.pt.2009.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinauskas V, Križanauskienė A, Iezhova TA, Bolshakov CV, Jönsson J, Bensch S, & Valkiūnas G (2013). A new method for isolation of purified genomic DNA from haemosporidian parasites inhabiting nucleated red blood cells. Experimental Parasitology, 133(3), 275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks DH, Rinke C, Chuvochina M, Chaumeil P-A, Woodcroft BJ, Evans PN, Hugenholtz P, & Tyson GW (2017). Recovery of nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes substantially expands the tree of life. Nature Microbiology, 2, 1533–1542. Doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli M, Chakarov N, Rupp O, Kalinowski J, Goesmann A, Sorenson MD, Krüger O, & Hoffman JI (2015). De novo assembly of the dual transcriptomes of a polymorphic raptor species and its malarial parasite. BMC Genomics 16:1038. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2254-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JC, Tarvin RD, O’Connell LA, Blackburn DC, & Coloma LA (2018). Diversity within diversity: Parasite species richness in poison frogs assessed by transcriptomics. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 125, 40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Zhang Y-Z, & Holmes EC (2018). Meta-transcriptomics and the evolutionary biology of RNA viruses. Virus Research, 243, 83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics, 30(9), 1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama M, Torrents D, & Bork P (2006). PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Research, 34(suppl_2), W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacutu R, Thornton D, Johnson E, Budovsky A, Barardo D, Craig T, … de Magalhaes JP (2018). Human ageing genomic resources: new and updated databases. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1083–D1090. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TR, Ramakrishnan K, Walshaw J, Heavens D, Alston M, Swarbreck D, … Poole PS (2013). Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals kingdom level changes in the rhizophere microbiome of plants. The ISME Journal, 7, 2248–2258. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkiūnas G (2004). Avian Malaria Parasites and other Haemosporidia. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valkiūnas G, Bensch S, Iezhova TA, Križanauskienė A, Hellgren O, & Bolshakov CV (2006). Nested cytochrome B polymerase chain reaction diagnostics underestimate mixed infections of avian blood haemosporidian parasites: microscopy is still essential. Journal of Parasitology, 92(2), 418–422. doi: 10.1645/GE-3547RN.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaumourin E, Vourc’h G, Gasqui P, & Vayssier-Taussat M (2015). The importance of multiparasitism: examining the consequences of co-infections for human and animal health. Parasites and Vectors, 8, 545. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videvall E, Cornwallis CK, Ahrén D, Palinauskas V, Valkiūnas G, & Hellgren O (2017). The transcriptome of the avian malaria parasite Plasmodium ashfordi displays host-specific gene expression. Molecular Ecology, 26(11), 2939–2958. doi: 10.1111/mec.14085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videvall E (2019). Genomic advances in avian malaria research. Trends in Parasitology, 35(3), 254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Field JT, Ilgūnas M, Bukauskaite D, Iezhova T, Valkiūnas G, & Sehgal RNM (2018). De novo transcriptome assembly and preliminary analysis of two avian malaria parasites, Plasmodium delichoni and Plasmodium homocircumflexum. Genomics, in press. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehtindjiev P, Krizanauskiene A, Bensch S, Palinauskas V, Asghar M, Dimitrov D, Scebba S, & Valkiūnas G (2012). A new morphologically distinct avian malaria parasite that fails detection by established polymerase chain reaction-based protocols for amplification of the cytochrome b gene. Journal of Parasitology, 98, 657–665. doi: 10.1645/GE-3006.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.