Abstract

Objective:

The specificity of the leukocyte esterase test (87%) is suboptimal. The objective of this study was to identify more specific screening tests that could reduce the number of children who unnecessarily receive antimicrobials to treat a presumed urinary tract infection (UTI).

Study Design:

Prospective cross-sectional study to compare inflammatory proteins in blood and urine samples collected at the time of a presumptive diagnosis of UTI. We also evaluated serum RNA expression in a subset.

Results:

We enrolled 200 children; of these 89 were later demonstrated not to have a UTI based on the results of the urine culture obtained. Urinary proteins that best discriminated between children with UTI and no UTI were involved in T-cell response proliferation (IL-9, IL-2), chemoattractants (CXCL12, CXCL1, CXCL8), the cytokine/interferon pathway (IL-13, IL-2, INFγ), or involved in innate immunity (NGAL). The predictive power (as measured by the area under the curve) of a combination of 4 urinary markers (IL-2, IL-9, IL-8, and NGAL) was 0.94. Genes in the pathways related to inflammation were also upregulated in serum of children with UTI.

Conclusions:

Urinary proteins involved in the inflammatory response may be useful in identifying children with false positive results with current screening tests for UTI; this may reduce unnecessary treatment.

Keywords: Prediction rule, risk, UTI, diagnostic accuracy, calculator

Table of Contents:

By measuring proteins in samples collected at the time of UTI diagnosis, this study identified specific urinary markers that may reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescription.

Introduction

Given that the prevalence of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children is low (i.e., many children are tested for each UTI detected) highly specific screening tests are needed so that empiric treatment can be restricted to those with a true UTI. Neither the leukocyte esterase nor leukocyte count obtained using urine conventional microscopy are sufficiently specific (specificities of 87% and 86%, respectively) [1]; approximately 50% of children initially treated with antibiotics for UTI based upon urinalysis are subsequently found to have a negative urine culture [2]. More specific markers would reduce the number of false positive results and reduce unnecessary antimicrobial use. In this study, we evaluated markers belonging to established inflammatory pathways that could be used in conjunction with the leukocyte esterase test to increase its specificity in the diagnosis of UTI.

METHODS

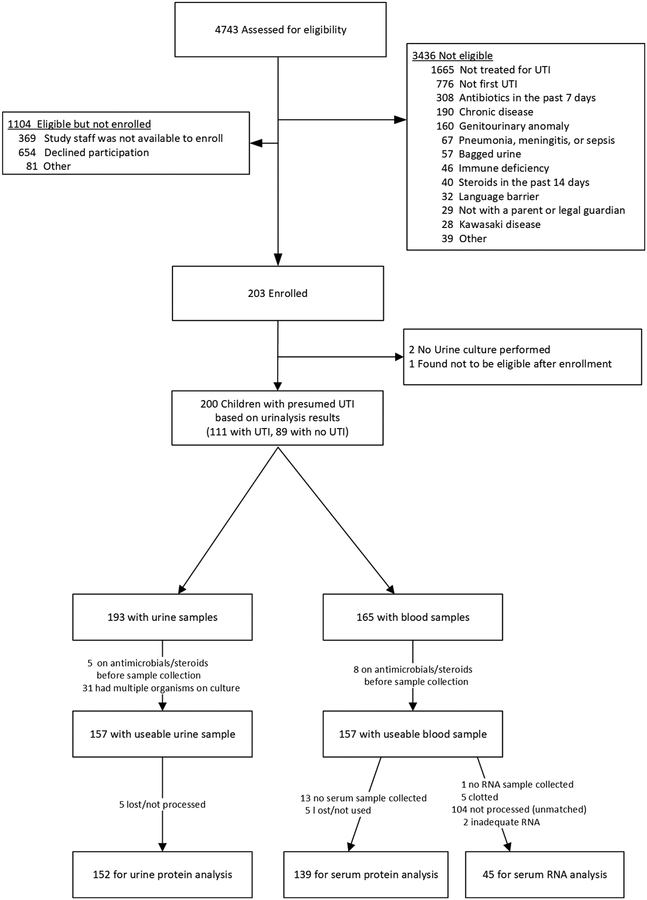

From October 2010 to June 2015, we prospectively enrolled a convenience sample of children 1 month to 10 years of age, at the time they presented to 1 of 3 Emergency Departments (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Children’s National Medical Center, Hasbro Children’s Hospital) or to one outpatient pediatric clinic affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, with fever and/or urinary symptoms. We included only children who were treated for UTI by the caring clinician and had pyuria on urinalysis or dipstick (≥10 WBC/mm3, or ≥5 WBC/hpf, or ≥1+ leukocyte esterase). Exclusion criteria are listed in Figure 1 and included recent antibiotics or steroids, chronic disease or genitourinary anomaly, another infectious condition (pneumonia, sepsis or meningitis), and bagged urine specimen. We defined a positive urine culture as growth of ≥100,000 CFU/mL of at least one uropathogen from a specimen collected by clean catch or ≥50,000 CFU/mL of at least one uropathogen from a catheterized specimen. There were no samples collected by suprapubic aspiration. No bagged urine specimens were used for urinalysis or culture. The institutional review board at each respective site approved this study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

Urine sample collection and processing for proteins

We used urine collected at the time of presentation in most instances; when this was not available, we collected an additional sample using a perineal collection bag. We filtered urine samples (Millex filters, Millipore) and stored them in cryovials at −80°C. Processing generally occurred within 1 hour of collection. However, if a delay was anticipated, samples were stored in a specimen refrigerator until processing.

Blood sample collection and processing for proteins

We collected blood samples from children whose parents consented to phlebotomy. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using Siemens Dimension Vista 500 Intelligent Lab System. Another aliquot was spun at 2700 rpm for 10 minutes and plasma was subdivided into multiple cryovials for protein measurement (cytokines, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and procalcitonin). Specimens were processed generally within 1 hour of collection, stored at −80°C and analyzed in batches.

Protein measurement

We assessed 53 candidate markers; 48 cyokines, NGAL, and DEFA1 (human alpha defensin 1) were measured in both blood and urine using Bio-Rad Pro Human Cytokine 27-plex and 21-plex plates (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), Thermo Fisher’s Rapid Human NGAL ELISA kit (KIT037; Waltham, MA) and Hycult DEFEA1 ELISA Kit (HK317; Hycult, Wayne, Pennsylvania), respectively. On each plate, we included duplicates and control samples. CRP and procalcitonin were measured in blood using Siemens Dimension Vista 500 Intelligent Lab System and bioMerieux’s miniVIDAS immunoanalyzer (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France), respectively. We measured urine creatinine concentration using R&D Creatinine Parameter Assay Kit (KGE005; R&D Systems, Minnepolis, Minnesota).

Statistical methods for protein data

We used logistic regression for binary variables and t-test for continuous variables (e.g. protein levels). In order to adjust for multiple comparison, the resulting p-values were converted to q-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction [3]. To access discriminative power, we constructed a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) using UTI vs no-UTI status as the outcome and calculated the area under the curve (AUC). Sensitivities and specificities were for the point on the ROC curve that maximized the Youden index (Youden index = sensitivity + specificity − 1). To evaluate the predictive power of combinations of biomarkers we used classification and regression tree (CART)[4] classifier from R package rpart. To be specific, leave-one-out cross validation was adopted to split the data into training set and testing set, and the predictive score of each testing sample was calculated using the classifier constructed by the training set. Samples or variables with missing values were removed. As a sensitivity analysis, we also present data for the subgroup of children with fever.

Serum RNA processing and sequencing methods

We used Applied Biosystems mini Tempus™ tubes to stabilize the RNA. Total RNA libraries were generated using Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Preparation Guide (Rev. E). First, we removed globin and ribosomal RNA using biotinylated, target-specific oligos combined with globin and rRNA removal beads. Following purification, RNA was fragmented into small pieces using divalent cations under elevated temperature. Cleaved RNA fragments were copied into first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers, followed by second strand cDNA synthesis using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. After ligation of the adapter, we added single ‘A’ base fragments to the cDNA fragments. We purified and enriched products with PCR to create the final cDNA library. We validated cDNA libraries using KAPA Biosystems primer premix kit with Illumina-compatible DNA primers and Qubit 2.0 fluorometer. We examined the quality of the RNA using Agilent Tapestation 2200. The cDNA libraries were pooled at a final concentration 1.8pM. Cluster generation and paired-read 75 bp sequencing was performed on Illumina NextSeq 500’s. The technician was blinded to the results of the corresponding patient’s urine culture results. Because of limitations in funding, RNA sequencing was undertaken in only a subset of children.

RNA-Seq data preprocessing

The RNA-seq data were aligned to Homo Sapiens UCSC hg19 using TopHat2 (TopHat v2.0.9) [5]. The expression count data of 23,710 unique genes and 45 samples were harvested after using HTseq to convert BAM files. Low expression genes with mean counts smaller than 5 were removed and 15,722 genes remained after this filtering step.

Statistical analysis of RNA data

We used edgeR [6] to detect differentially expressed (DE) genes. Because of the relatively small sample size, we used p-values at 0.05 and fold change 1.5 as the threshold to determine DE genes. In order to investigate the functional annotation of the DE genes, we applied enrichment analysis using the database provided by Chaussabel [7] using Fisher’s exact test. In addition, we performed pathway enrichment analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA).

RESULTS

Figure 1 describes the flow of children into the study. Compared to excluded children, included children were less likely to be White (p<0.001) and more likely to be older (p<0.001). Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the 111 children with UTI and the 89 children with no UTI. Mean age of the children we included was 4.5 years. Children with UTIs were younger, were more likely to have fever, were febrile for longer duration and had a higher maximum temperature. Mean creatinine level in the two groups did not differ significantly (p=0.39), nor did the number of children receiving ibuprofen (p=0.99). A urine collection bag was used in 4 children for collection of urinary proteins. Of the 57 children <24 months of age, 56 were febrile and 54 had samples obtained by catheterization.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the children includeda

| Characteristic | No UTIb (N=89) | UTIc (N=111) |

|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Age (months) | ||

| 1–11 | 12 (13.5) | 28 (25.2) |

| 12–23 | 3 (3.4) | 14 (12.6) |

| 24–59 | 27 (30.3) | 32 (28.8) |

| ≥60 | 47 (52.8) | 37 (33.3) |

| Sex/circumcision | ||

| Female | 78 (87.6) | 102 (91.9) |

| Uncircumcised male | 5 (5.6) | 3 (2.7) |

| Circumcised male | 6 (6.7) | 6 (5.4) |

| Race | ||

| White | 36 (40.4) | 57 (51.4) |

| Black | 31 (34.8) | 36 (32.4) |

| Asian | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.7) |

| Unknown | 19 (21.4) | 15 (13.5) |

| Fever | ||

| Yes | 44 (49.4) | 83 (74.8) |

| No | 45 (50.6) | 28 (25.2) |

| Duration of Fever | ||

| No fever | 45 (50.6) | 28 (25.2) |

| ≥ 48 hours | 17 (19.1) | 33 (29.7) |

| < 48 hours | 25 (28.1) | 47 (42.3) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.2) | 3 (2.7) |

| Maximum Reported Temperature | ||

| ≥ 39° C | 26 (29.2) | 52 (46.8) |

| < 39° C | 63 (70.8) | 59 (53.2) |

| Method of collection | ||

| Catheter | 17 (19.1) | 48 (43.2) |

| Clean Catch | 72 (80.9) | 63 (56.8) |

| Dysuria, urgency, frequency, or new onset incontinence | ||

| Yes | 50 (56.2) | 59 (53.2) |

| No | 28 (31.4) | 19 (17.1) |

| Not applicable (i.e., not toilet trained) | 11 (12.4) | 33 (29.7) |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Yes | 5 (5.6) | 105 (94.6) |

| No | 84 (94.4) | 6 (5.4) |

All children included either had a positive leukocyte esterase test or evidence of pyuria on urine microscopy. All were symptomatic and all were treated with antimicrobials for a presumed UTI by the caring provider.

UTI defined by growth of a uropathogen at growth of ≥100,000 CFU/mL of at least one uropathogen from a specimen collected by clean catch or ≥50,000 CFU/mL of at least one uropathogen from a catheterized specimen. 4 children with UTI had significant (≥10,000 CFU/mL) growth of another organism.

8 children with no UTI had significant growth of uropathogens (>10,000 CFU/mL) but at lower counts than required for a UTI.

Protein markers

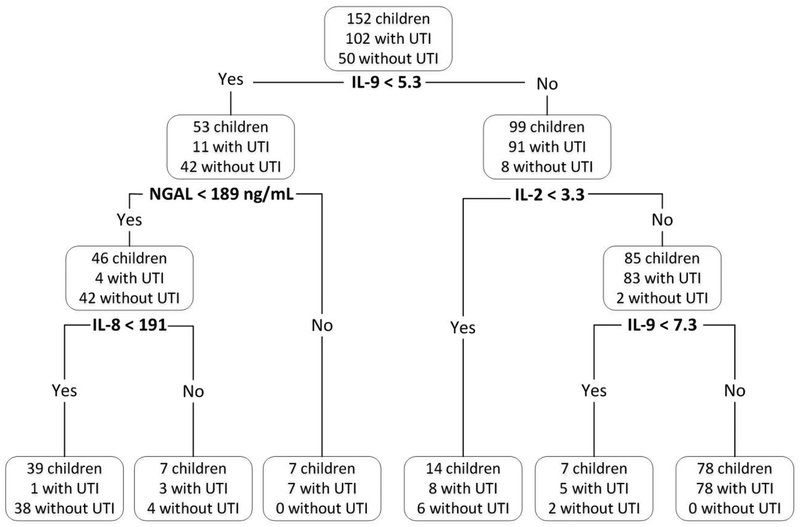

The urinary markers that best discriminated (i.e., AUC ≥0.85 and q<0.0001) between children with UTI and no UTI (Table 2 for top 30 markers, Supplementary Table 4s for complete list of all significant markers) were proteins involved in T-cell response proliferation (IL-9, IL-2), cytokine/interferon pathway (IL-13, IL-2, INFγ), innate immunity (NGAL) and response to infection (TNFα, IL-17A), as well as chemoattractants for monocytes (CXCL12) and neutrophils (CXCL1, CXCL8). Division of protein marker level by urine creatinine had little effect on the p-values or the AUC of the urinary markers; accordingly, we present only raw values in the tables included in this report. The predictive power (as measured by the AUC, Figure 2) of a combination of 4 urinary markers (IL-2, IL-9, IL-8, and NGAL) using the CART model with leave-one-out cross-validation was 0.94, with a sensitivity of 0.96 (95% CI: [0.92, 1.00]) and a of specificity 0.84 (95% CI: [0.74, 0.94]).

Table 2.

Univariate association between top 30 biomarkers and urinary tract infection (UTI) in urine and serum by decreasing Q value.a

| Biomarker | Number (No UTI/UTI) | Mean (SD) level in No UTI (pg/mL) | Mean (SD) level in UTI (pg/mL) | Q value | AUC | Sensitivityb | Specificityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary markers | |||||||

| IL-9 | 50/102 | 3.50 (3.36) | 14.91 (9.54) | 6.30E-18 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.92 |

| CXCL12 (SDF1) | 50/102 | 71.68 (31.92) | 136.79 (61.41) | 3.84E-13 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| IL-13 | 50/102 | 2.43 (1.21) | 4.89 (2.96) | 5.78E-10 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.94 |

| Interferon γ | 50/102 | 10.50 (18.54) | 39.93 (39.93) | 2.96E-09 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.86 |

| NGAL | 50/103 | 140023.14 (337843.37) | 620493.72 (554538.14) | 1.13E-08 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| PDGF | 50/102 | 5.07 (3.56) | 17.33 (18.56) | 3.39E-08 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.96 |

| TNF α | 50/102 | 3.98 (2.81) | 14.54 (16.18) | 4.05E-08 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| IL-2 | 50/102 | 2.28 (1.67) | 9.21 (10.77) | 4.96E-08 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| IL-12 | 50/102 | 35.63 (23.44) | 67.03 (42.50) | 2.55E-07 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.66 |

| CXCL1 (GROα) | 50/102 | 325.13 (826.33) | 1415.24 (1539.32) | 5.04E-07 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.86 |

| IL-16 | 50/102 | 73.45 (61.40) | 521.25 (799.99) | 1.03E-06 | 0.78 | 0.46 | 0.98 |

| IL-5 | 50/102 | 0.42 (0.97) | 2.30 (3.16) | 1.07E-06 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| IL-4 | 50/102 | 0.41 (0.28) | 0.95 (0.92) | 1.46E-06 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| CCL4 (MIP-1β) | 50/102 | 63.01 (117.88) | 299.01 (465.03) | 1.82E-05 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| IL-8 | 50/102 | 142.18 (236.21) | 1086.23 (1954.96) | 2.12E-05 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

| SCGF β | 50/102 | 734.07 (671.90) | 2418.95 (3467.73) | 2.62E-05 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| IL-17A | 50/102 | 11.96 (26.66) | 47.28 (68.45) | 4.40E-05 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

| FGF (basic) | 50/102 | 19.30 (17.40) | 33.23 (17.99) | 5.02E-05 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.80 |

| MIP-1a | 50/102 | 1.23 (3.56) | 8.82 (17.51) | 0.000180088 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| Serum markers | |||||||

| Interferon α2 | 67/72 | 9.98 (19.77) | 42.83 (18.53) | 2.76E-16 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| CXCL12 (SDF1) | 67/72 | 233.41 (92.13) | 387.42 (102.47) | 1.28E-14 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

| FGF (basic) | 66/71 | 19.91 (31.12) | 70.56 (50.65) | 2.13E-09 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| SCGF β | 67/72 | 10097.59 (10921.95) | 27334.10 (18837.83) | 1.48E-08 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor | 67/72 | 6.68 (6.21) | 13.73 (6.52) | 1.48E-08 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.88 |

| IL-18 | 67/72 | 44.83 (36.02) | 93.97 (58.82) | 2.22E-07 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.73 |

| CCL5 (RANTES) | 66/71 | 6919.59 (3038.73) | 10155.59 (3615.38) | 5.39E-07 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| IL-3 | 67/72 | 27.63 (52.54) | 125.84 (134.92) | 8.09E-07 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.78 |

| IL-2 receptor α | 67/72 | 111.09 (84.50) | 209.47 (123.80) | 1.16E-06 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| IL-7 | 66/71 | 49.04 (34.21) | 25.07 (16.48) | 6.61E-06 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.82 |

| IL-17A | 66/71 | 34.19 (34.20) | 83.72 (94.34) | 0.000268492 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.70 |

Q value represents p value corrected for multiple comparisons.

Sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of UTI in children with evidence of pyuria. These values were determined using cutoff that maximized the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity −1).

Figure 2.

Accuracy of a combination of 4 urinary markers in diagnosing urinary tract infection (area under the ROC curve = .94)

Serum markers that best differentiated children with UTI from those with no UTI included: interferon α2 (involved in cytokine signaling), CXCL12 (chemoattractant for monocytes), and IL-3 (Table 2). A combination of 5 serum markers (interferon α2, CXCL12, HGF, CCL5, and NGAL) identified by CART achieved the highest accuracy; its predictive power (as measured by the AUC) was 0.85, with a sensitivity of 0.82 (95% CI: [0.74, 0.89]) and a specificity of 0.88 (95% CI: [0.81, 0.95]). Unlike a previous study [8], we did not find differences in the levels of urinary human neutrophil peptide 1 (or its gene: human α-defensin 1) in the two groups.

Supplementary Table 5s presents the protein biomarkers in the subgroup of children that were febrile. Supplementary Table 6s presents the results after excluding 12 children with possible contamination (4 children with UTI with significant growth (≥10,000 CFU/mL) of >1 uroopathogens and 8 children without UTI who had significant growth (≥10,000 CFU/mL) of one uropathogen at counts lower than those required for a UTI). Results in these two sensitivity analyses were generally similar to the overall results.

RNA expression data

RNA sequencing was only performed on febrile children who had not received antibiotics or corticosteroids before sample collection and for whom we had collected a serum sample that had adequate concentrations of RNA. Furthermore, because of cost, RNA sequencing was only attempted on a subset; we included all children with pyelonephritis confirmed by DMSA, a matched (by age and duration of fever) group of febrile children with cystitis, and all febrile children who had no growth on culture. A total of 36 children with UTI and 9 children with no UTI were included in this analysis (Figure 1). All had fever and 3 were males. By controlling p-values at 0.05 and absolute fold change at 1.5, we obtained 345 differentially expressed (DE) transcripts. The expression levels of the DE genes can be visualized in Figure 1s in the appendix; the list of the top 25 DE genes is shown in Supplementary Table 1s. Modular analysis (Supplementary Table 2s) using Chaussabel’s database showed that neutrophil response differed significantly in children with UTI and no UTI [7]. Pathway analysis (Supplementary Table 3s) revealed several candidate pathways with biological plausibility that differ significantly in children with and without UTI.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified urinary and serum markers that appear promising in differentiating children with pyuria who do and do not have UTI. Particularly promising single markers include urinary IL-9, IL-2, IL-8, and NGAL. At present, NGAL can be measured commercially and ELISA tests are available for the 3 interleukins. These findings suggest that differences in easily measurable inflammatory proteins in the urine might be useful in differentiating children with and without UTI. Because collection of blood samples is not routinely performed in children with suspected UTI, and because accuracy of serum markers was lower than for urinary markers, it seems prudent to focus on urinary markers.

To understand the implications of our findings, imagine a hypothetical cohort of 1000 children being tested for UTI using the leukocyte esterase test, of whom 7% [9] (or 70) are assumed to have a UTI. Of the 70 children with UTI, the leukocyte esterase test will identify 55 (because the sensitivity of the test is 79% [1]). Of the 930 without UTI, 13% (i.e. 121) will be incorrectly identified as having a UTI (because the specificity of the test is 87% [1]). Assuming that children with a positive leukocyte esterase are empirically treated with antimicrobials, applying the panel of 4 urinary markers identified here to the 176 children (55 + 121) with a positive leukocyte esterase test would reduce the number of children receiving unnecessary antibiotics from 121 to 19 (because the specificity of the panel is 84%) without significantly reducing the number of children with UTI who are appropriately treated with antibiotics (because the sensitivity of the panel is 96%).

A role for the 4 previously mentioned urinary markers is supported by their pathophysiological role and by previous studies of these markers as diagnostic tools. IL-9 is involved in growth of helper T-cells, and these cells have been shown to play a role in the immune response to UTI [10]. Furthermore, in one study, adults with UTI had significantly higher levels of IL-9 compared to age- and gender-matched healthy controls [11]. IL-2 is involved with T cell growth and differentiation following activation by an antigen [12, 13], and its receptor is present on neutrophils [14]. IL-8 is a key neutrophil chemoattractant in the urinary tract, directing the migration of neutrophils across the mucosa and into the urine [15], which is elevated in adults and children with UTI [16, 17]. We found significant differences in NGAL levels (in urine and serum) and in the gene coding for NGAL (LCN2) between the 2 groups. Although the function of NGAL is not completely understood, it plays a role in sequestering iron required for bacterial growth. It is released from neutrophils, and to a smaller degree from intercalated cells in the renal collecting duct in response to infection or cell injury [18]. Several studies have found that NGAL differs in children with and without UTI, both in serum and/or blood [19–23].

Of the genes identified though RNA sequencing that are supported by previous studies (i.e. LTF, AZUI, CEACAM8, DEFA4, in Supplementary Table 1s and CAMP in Supplementary Table 2s), most seem to have an antibacterial role. Lactotransferrin (also known as lactoferrin, encoded by LTF) interferes with iron uptake and thereby causes bacterial cell lysis. Azurocidin (encoded by AZUI), present in azurophil granules of neutrophils, has activity against gram-negative bacteria [24]. DEFA4 (also known as HNP-4) and CAMP encode for antimicrobial peptides (defensin alpha 4 and cathelicidin, respectively). Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecules (CECAM) are glycoproteins expressed on mucosal surfaces which are thought to be involved in pathogen colonization [25, 26]. All 5 genes (or their products) have been implicated in UTI or colonization in previous studies [25–34]. Our data was slightly puzzling because, even though all of the above genes are involved in the defense against UTI, we found that all were underexpressed in children with UTI. One explanation might be that children who fail to effectively upregulate expression of these genes are more susceptible to UTI. Indeed, some support for this hypothesis comes from a recent study that found children with increased risk of UTI recurrences had fewer copies of α-defensin-encoding DEFA1A3 [31]

Analysis of the gene pathways (Supplementary Table 3s) identified several pathways that appear to have clinical plausibility. Specifically, our data suggests that leukocyte extravasation, natural killer cell signaling, IL-6 and IL-2 signaling, and T-cell pathways are important in the pathophysiology of UTI. These findings are generally consistent with previous studies [12, 17, 35–43]. Of note, both pathway analysis of gene expression in the serum and urinary protein measurement suggest that IL-2 signaling could also be important in the immune response to UTI. To our knowledge, other than one tangentially-related study [44], this is a novel finding.

Our study was limited because the recruited sample did not provide us with adequate power to examine potentially important subgroup differences. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, although possible, is unlikely because all patients were symptomatic to the extent that clinicians tested and treated for UTI and all had pyuria. As with most studies on pediatric UTI, a small proportion children categorized as having a UTI, may have actually had contamination of the sample during collection. We attempted to minimize this by avoiding bag-collected urine samples for diagnosis of UTI, by requiring pyuria, and by using established cutoff-offs to define a UTI. Furthermore, as a sensitivity analysis, we present the results in which we exclude children with possible contamination. A strength of the study is performance of both RNA sequencing and protein measurement, which appear to have provided complimentary data.

In conclusion, this study provides preliminary evidence to support a role for measurement of urinary IL-9, IL-2, IL-8, NGAL, and preliminary support for the use of an RNA signature in differentiating, among children with pyuria, those with UTI from those without UTI. These markers, if confirmed by future studies, could be useful in reducing unnecessary antimicrobial use for children with presumed UTI.

Supplementary Material

What is known on this subject:

Neither the leukocyte esterase nor leukocyte count obtained using microscopy are sufficiently specific; many children treated for UTI based on the results of these tests have no growth on urine culture.

What this study adds:

We have identified 4 urinary proteins that in combination accurately differentiate, among children with pyuria, those with UTI from those without UTI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts to declare

References

- 1.Williams GJ, Macaskill P, Chan SF, Turner RM, Hodson E, Craig JC (2010) Absolute and relative accuracy of rapid urine tests for urinary tract infection in children: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 10:240–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Hum SW, Alberty A, Muniz G, Kurs-Lasky M, Landsittel D, Shope T (2018) Development and Validation of a Calculator for Estimating the Probability of Urinary Tract Infection in Young Febrile Children. JAMA Pediatr 172:550–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I (2001) Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 125:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ (1984) Classification and regression trees. Wadsworth, Inc., Monterey, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14:R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone AF, Mendall MA, Kaski JC, Edger TM, Risley P, Poloniecki J, Camm AJ, Northfield TC (2002) Effect of treatment for Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori on markers of inflammation and cardiac events in patients with acute coronary syndromes: South Thames Trial of Antibiotics in Myocardial Infarction and Unstable Angina (STAMINA). Circulation 106:1219–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaussabel D, Quinn C, Shen J, Patel P, Glaser C, Baldwin N, Stichweh D, Blankenship D, Li L, Munagala I, Bennett L, Allantaz F, Mejias A, Ardura M, Kaizer E, Monnet L, Allman W, Randall H, Johnson D, Lanier A, Punaro M, Wittkowski KM, White P, Fay J, Klintmalm G, Ramilo O, Palucka AK, Banchereau J, Pascual V (2008) A modular analysis framework for blood genomics studies: application to systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunity 29:150–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson JR, Hains DS, Cohen DM, Spencer JD, Kline JM, Yin H, Schwaderer AL (2016) Evaluation of novel urinary tract infection biomarkers in children. Pediatr Res 79:934–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH (2008) Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27:302–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noelle RJ, Nowak EC (2010) Cellular sources and immune functions of interleukin-9. Nat Rev Immunol 10:683–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundac L, Dando SJ, Sullivan MJ, Derrington P, Gerrard J, Ulett GC (2016) Protein-based profiling of the immune response to uropathogenic Escherichia coli in adult patients immediately following hospital admission for acute cystitis. Pathog Dis 74(6). doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao W, Lin JX, Leonard WJ (2011) IL-2 family cytokines: new insights into the complex roles of IL-2 as a broad regulator of T helper cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol 23:598–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross SH, Cantrell DA (2018) Signaling and Function of Interleukin-2 in T Lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 36:411–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard D, Gosselin J, Heitz D, Paquin R, Beaulieu AD (1995) Effects of interleukin-2 on gene expression in human neutrophils. Blood 86:1170–1176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godaly G, Ambite I, Puthia M, Nadeem A, Ho J, Nagy K, Huang Y, Rydstrom G, Svanborg C (2016) Urinary Tract Infection Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Translation. Pathogens 5(1). doi: 10.3390/pathogens5010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko YC, Mukaida N, Ishiyama S, Tokue A, Kawai T, Matsushima K, Kasahara T (1993) Elevated interleukin-8 levels in the urine of patients with urinary tract infections. Infect Immun 61:1307–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krzemien G, Szmigielska A, Turczyn A, Panczyk-Tomaszewska M (2016) Urine interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and transforming growth factor beta1 in infants with urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria. Cent Eur J Immunol 41:260–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paragas N, Kulkarni R, Werth M, Schmidt-Ott KM, Forster C, Deng R, Zhang Q, Singer E, Klose AD, Shen TH, Francis KP, Ray S, Vijayakumar S, Seward S, Bovino ME, Xu K, Takabe Y, Amaral FE, Mohan S, Wax R, Corbin K, Sanna-Cherchi S, Mori K, Johnson L, Nickolas T, D’Agati V, Lin CS, Qiu A, Al-Awqati Q, Ratner AJ, Barasch J (2014) alpha-Intercalated cells defend the urinary system from bacterial infection. J Clin Invest 124:2963–2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal I, Iswarya J, Flemming J, Chaturvedi S, Mathew LG, Varkey SD, Sahni RD (2013) Prospective study to determine the usefulness of urinary neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin(NAGL) as an early and sensitive marker of urinary tract infection (UTI) in children. Pediatr Nephrol 28:1358 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung N, Byun HJ, Park JH, Kim JS, Kim HW, Ha JY (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of urinary biomarkers in infants younger than 3 months with urinary tract infection. Korean J Pediatr 61:24–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HE, Kim DK, Kang HK, Park K (2015) The diagnosis of febrile urinary tract infection in children may be facilitated by urinary biomarkers. Pediatr Nephrol 30:123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubell TR, Barasch JM, Xu K, Ieni M, Cabrera KI, Dayan PS (2017) Urinary Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for the Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections. Pediatrics 140(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valdimarsson S, Jodal U, Barregard L, Hansson S (2017) Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and other biomarkers in infants with urinary tract infection and in febrile controls. Pediatr Nephrol 32:2079–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida RP, Vanet A, Witko-Sarsat V, Melchior M, McCabe D, Gabay JE (1996) Azurocidin, a natural antibiotic from human neutrophils: expression, antimicrobial activity, and secretion. Protein Expr Purif 7:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korotkova N, Yarova-Yarovaya Y, Tchesnokova V, Yazvenko N, Carl MA, Stapleton AE, Moseley SL (2008) Escherichia coli DraE adhesin-associated bacterial internalization by epithelial cells is promoted independently by decay-accelerating factor and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule binding and does not require the DraD invasin. Infect Immun 76:3869–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muenzner P, Kengmo Tchoupa A, Klauser B, Brunner T, Putze J, Dobrindt U, Hauck CR (2016) Uropathogenic E. coli Exploit CEA to Promote Colonization of the Urogenital Tract Mucosa. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arao S, Matsuura S, Nonomura M, Miki K, Kabasawa K, Nakanishi H (1999) Measurement of urinary lactoferrin as a marker of urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol 37:553–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan Y, Sonn GA, Sin ML, Mach KE, Shih MC, Gau V, Wong PK, Liao JC (2010) Electrochemical immunosensor detection of urinary lactoferrin in clinical samples for urinary tract infection diagnosis. Biosens Bioelectron 26:649–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Y, Zielinski MD, Rolfe MA, Kuntz MM, Nelson H, Nelson KE, Pieper R (2015) Similar Neutrophil-Driven Inflammatory and Antibacterial Responses in Elderly Patients with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. Infect Immun 83:4142–4153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjolvmark C, Pahlman LI, Akesson P, Linder A (2014) Heparin-binding protein: a diagnostic biomarker of urinary tract infection in adults. Open Forum Infect Dis 1:ofu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwaderer AL, Wang H, Kim S, Kline JM, Liang D, Brophy PD, McHugh KM, Tseng GC, Saxena V, Barr-Beare E, Pierce KR, Shaikh N, Manak JR, Cohen DM, Becknell B, Spencer JD, Baker PB, Yu CY, Hains DS (2016) Polymorphisms in alpha-Defensin-Encoding DEFA1A3 Associate with Urinary Tract Infection Risk in Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol 27:3175–3186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chromek M, Slamova Z, Bergman P, Kovacs L, Podracka L, Ehren I, Hokfelt T, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL, Agerberth B, Brauner A (2006) The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection. Nat Med 12:636–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babikir IH, Abugroun EA, Bilal NE, Alghasham AA, Abdalla EE, Adam I (2018) The impact of cathelicidin, the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in urinary tract infections. BMC Infect Dis 18:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen KL, Dynesen P, Larsen P, Jakobsen L, Andersen PS, Frimodt-Moller N (2014) Role of urinary cathelicidin LL-37 and human beta-defensin 1 in uncomplicated Escherichia coli urinary tract infections. Infect Immun 82:1572–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godaly G, Proudfoot AE, Offord RE, Svanborg C, Agace WW (1997) Role of epithelial interleukin-8 (IL-8) and neutrophil IL-8 receptor A in Escherichia coli-induced transuroepithelial neutrophil migration. Infect Immun 65:3451–3456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hordijk PL (2016) Recent insights into endothelial control of leukocyte extravasation. Cell Mol Life Sci 73:1591–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koskinen K, Vainio PJ, Smith DJ, Pihlavisto M, Yla-Herttuala S, Jalkanen S, Salmi M (2004) Granulocyte transmigration through the endothelium is regulated by the oxidase activity of vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1). Blood 103:3388–3395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watzl C, Long EO (2010) Signal transduction during activation and inhibition of natural killer cells. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 11:Unit 11 19B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gur C, Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Rosenberg S, Yamin R, Enk J, Glasner A, Bar-On Y, Fleissig O, Naor R, Abed J, Mevorach D, Granot Z, Bachrach G, Mandelboim O (2013) Natural killer cell-mediated host defense against uropathogenic E. coli is counteracted by bacterial hemolysinA-dependent killing of NK cells. Cell Host Microbe 14:664–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isaacson B, Hadad T, Glasner A, Gur C, Granot Z, Bachrach G, Mandelboim O (2017) Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1 Mediates Immune Cell Attraction upon Urinary Tract Infection. Cell Rep 20:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benson M, Jodal U, Andreasson A, Karlsson A, Rydberg J, Svanborg C (1994) Interleukin 6 response to urinary tract infection in childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J 13:612–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su H, Lei CT, Zhang C (2017) Interleukin-6 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Kidney Disease: An Update. Front Immunol 8:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hannan TJ, Mysorekar IU, Hung CS, Isaacson-Schmid ML, Hultgren SJ (2010) Early severe inflammatory responses to uropathogenic E. coli predispose to chronic and recurrent urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleischmann JD, Wentworth DB, Thomas KM, Imbembo AL (1989) Urinary interleukin-2 inhibition in patients with cystitis. Immunol Invest 18:825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.