Abstract

Objective

To describe the epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) healthcare-associated infections (HAI) in Egyptian hospitals reporting to the national HAI surveillance system.

Methods

Design: Descriptive analysis of CRE HAIs and retrospective observational cohort study using national HAI surveillance data. Setting: Egyptian hospitals participating in the HAI surveillance system. The patient population included patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in participating hospitals. Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases were Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter isolates from blood, urine, wound or respiratory specimen collected on or after day 3 of ICU admission. CRE HAI cases were those resistant to at least one carbapenem. For CRE HAI cases reported during 2011–2017, a hospital-level and patient-level analysis were conducted using only the first CRE isolate by pathogen and specimen type for each patient. For facility, microbiology, and clinical characteristics, frequencies and means were calculated among CRE HAI cases and compared with carbapenem-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases through univariate and multivariate logistic regression using STATA 13.

Results

There were 1598 Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases, of which 871 (54.1%) were carbapenem resistant. The multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that carbapenem resistance was associated with specimen type, pathogen, location prior to admission, and length of ICU stay. Between 2011 and 2017, there was an increase in the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases due to CRE (p-value = 0.003) and the incidence of CRE HAIs (p-value = 0.09).

Conclusions

This analysis demonstrated a high and increasing burden of CRE in Egyptian hospitals, highlighting the importance of enhancing infection prevention and control (IPC) programs and antimicrobial stewardship activities and guiding the implementation of targeted IPC measures to contain CRE in Egyptian ICU’s .

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Carbapenem resistance Enterobacteriaceae, Healthcare-associated infections

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is being increasingly recognized as a global health security threat that requires integrated action across government sectors and society as a whole [1]. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are especially concerning pathogens due to their resistance to last resort antibiotics [2–4], high morbidity and mortality, and the high potential for their resistance to spread via mobile genetic elements [5, 6].

CRE are often associated with healthcare transmission, as demonstrated in the United States, where more than 9000 healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are caused by CRE each year [7, 8]. Healthcare-related risk factors associated with CRE infection include prolonged hospital stay, presence of invasive medical devices, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and previous exposure to antimicrobials [9–12]. Data on these risk factors are useful to guide CRE prevention and control efforts, but most data describing CRE epidemiology are reported from high resource settings [13].

The healthcare system in Egypt includes a network of secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities in the public, university, or private sector in 27 geographic regions or governorates. Egypt is one of the first countries in World Health Organization’s (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) to develop a prospective, standardized national HAI surveillance system. Established in May 2011, Egypt’s HAI surveillance system aims to estimate HAI prevalence and incidence, establish national benchmarks, and describe HAI-causing pathogens in order to inform prevention activities [14, 15]. Using data from Egypt’s national HAI surveillance program, we described HAIs caused by CRE to examine burden, trends, and risk factors associated with CRE HAIs in ICU patients compared to those with carbapenem-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae (CSE) HAIs.

Methods

Egyptian HAI surveillance system

Egypt’s HAI surveillance system was implemented in a phased approach, with 310 ICUs in 72 hospitals across 25 governorates collecting data between 2011 to 2017. Hospitals were selected to participate in the surveillance system based on the presence of hospital management support, well-trained infection prevention and control (IPC) teams including link IPC nurses in ICUs, adequate microbiology laboratory capacity (i.e., ability to conduct pathogen identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing [AST]), and data entry capacity. The surveillance system focuses on the four most common types of HAIs in ICU patients as identified by data from the first year of Egypt’s HAI surveillance program [14, 15]: bloodstream infections (BSI), urinary tract infections (UTI), pneumonia (PNA), and surgical site infections (SSI). The methodology of the national HAI surveillance program, including HAI definitions, have been described in earlier publications [14, 15].

Definitions

HAI surveillance definitions used for BSI, UTI, PNA, and SSI were derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) 2012 National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) [16], with minor adaptations for the primary BSI case definition. Cases of HAI with a culture growing an Enterobacteriaceae from a blood, urine, respiratory tract, or surgical site were included in this analysis. CRE cases were HAIs with Enterobacteriaceae isolates resistant to at least one of the following carbapenems: imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem [17]. CSE cases were HAIs with Enterobacteriaceae isolates not resistant to any of these carbapenems. This analysis was focused on the most common Enterobacteriaceae pathogens according to existing AMR data from Egypt, and included Klebsiella spp (only K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca aggregated, but not other rare species), Escherichia coli and Enterobacter spp [18].

Microbiological testing

On a monthly basis, all isolates associated with signs or symptoms of infection were sent to the AMR reference laboratory for confirmatory identification and AST for quality control purposes. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using disk diffusion (Becton Dickinson, USA) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (CLSI) [19]. Only microbiologic confirmatory testing data from the AMR reference lab were used for this analysis to ensure accurate laboratory results.

Electronic data collection, entry, and reporting

Egypt’s HAI surveillance program uses electronic data collection methods and automated analysis, thereby reducing the workload on hospital HAI surveillance coordinators (SC) and ensuring timeliness of reporting and feedback. To identify cases, the hospital SC screens ICU patients for new clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of infection (fever, crackles, cough, etc.) at least 3 days per week by reviewing medical records, interviewing physicians, and reviewing diagnostic test results (microbiology results or radiology reports). When microbiology results are not available, the physician requests appropriate specimens to be collected for microbiology testing. When a patient is suspected of a HAI based on signs, symptoms, or diagnostic test results, patient information is entered into a standardized case report form installed on the electronic device. The device automatically analyzes the entered data to determine whether the patient meets the HAI case definition and if so, specifies the type of infection. Denominator data (i.e., patient-days, central line–days, urinary catheter–days, ventilator-days) are entered daily on a standardized denominator reporting form installed on the device. The clinical and epidemiological HAI data are uploaded weekly to a secured web-based surveillance application [15] . HAI microbiological data produced by the AMR reference laboratory are also uploaded to the web application, where the data are merged with the HAI clinical and epidemiological data. The web application has built in data quality checks and analytic tools for immediate data cleaning and analysis, which allows hospital teams to generate automated individualized facility reports.

Data variables

The following patient data were available for each case: patient demographics (i.e., age, sex), hospital and ICU type as defined by NHSN [20, 21], admission and discharge date, length of ICU stay prior to specimen collection, location prior to ICU admission, symptoms that met the case definition, presence of invasive devices, associated surgical procedures in last 90 days, radiological results, and patient outcome (i.e. death, discharged). Relevant microbiology data were also collected including specimen type, specimen collection date, pathogen, and AST results.

Statistical analysis

Data on CRE and CSE cases identified between May 2011 and December 2017 were included in this analysis. An isolate-level analysis of all Enterobacteriaceae isolates from CRE and CSE cases, including multiple isolates from an individual case, was conducted to calculate the proportion of CRE isolates among all Enterobacteriaceae isolates, stratified by pathogen. A hospital-level analysis was conducted by calculating the proportion of hospitals with ≥1 CRE positive specimen among hospitals conducting HAI surveillance, stratifying by hospital type and size.

For the patient-level analysis, patients were counted as being a CRE case if they had any sample positive for CRE; however, patients with multiple Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the same admission, but from different specimen sites or different dates were counted only once. For patients with multiple isolates, only the first CRE isolate was included in the analysis. Frequencies of categorical variables were stratified by CRE status and compared between CRE and CSE cases using χ2 test or 2-tailed Fisher Exact test. For continuous variables, means with standard deviations (or medians and interquartile ranges if distributions were skewed) were stratified by CRE status and compared between CRE and CSE cases using Student t test or Mann–Whitney test, dependent on the validity of normality assumption.

Univariate analysis was performed using logistic regression to calculate odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values to determine the strength of the association between these variables and CRE status. The reference category was assigned based on the category with the highest frequency of Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases, except in the analysis of ICU category, where Surgical Critical Care was used as the reference because the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was considered too specialized to serve as the reference. Variables with chi-square test p-value < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were then included into a multivariable logistic regression model, using a forward stepwise approach to identify risk factors associated with CRE status. Variables were kept in the final model if the p-value for the likelihood ratio test was < 0.05. All analysis were performed using STATA 13 [22].

Incidence rates for CRE cases were calculated as the proportion of CRE cases per 10,000 patient days [20]. For the trend analysis, χ2 test was used to determine statistical significance of the trend in CRE case incidence and proportion of CRE cases among all Enterobacteriaceae cases.

Results

A total of 3836 Enterobacteriaceae isolates from 3109 patients were reported to Egypt’s HAI surveillance system from 2011 to 2017. For the isolate-level analysis, 1105 (47.9%) of the 2306 Enterobacteriaceae isolates submitted to the AMR reference laboratory were CRE [Table 1]. When stratified by pathogen, approximately half of Klebsiella (n = 929, 53.7%) and Enterobacter (n = 54, 43.5%) isolates were CR, while a smaller percentage of Escherichia coli isolates (n = 122, 27.1%) were CRE. The overall incidence of HAI due to CRE was 3.7 per 10,000 patient-days. Among the 72 hospitals performing HAI surveillance, 46 (63.9%) reported at least one CRE isolate during the study period, but this percentage varied by hospital type and hospital size (Table 2).

Table 1.

Enterobacteriaceae isolates* with Carbapenem resistance by type of organism, May 2011 – December 2017

| No. isolates tested for Carbapenem resistance | No. isolates with Carbapenem resistance | % Carbapenem resistant * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella | 1731 | 929 | 53.7 |

| Escherichia coli | 451 | 122 | 27.1 |

| Enterobacter | 124 | 54 | 43.5 |

| Total | 2306 | 1105 | 47.9 |

*out of all Enterobacteriaceae isolates with all isolates from each patient included

Table 2.

Number and percentage of hospitals reporting Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from HAI surveillance by selected characteristics, May 2011 – December 2017

| Characteristics | Total no. of hospitals performing HAI surveillance N = 72 |

No. hospitals reporting ≥ 1 CRE positive specimen N = 46 |

% reporting ≥ 1 CRE positive specimen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital type* | |||

| Medical | 15 | 8 | 53.3 |

| General | 30 | 21 | 70 |

| Surgical | 15 | 8 | 53.3 |

| Obstetrics | 5 | 4 | 80 |

| Pediatrics | 7 | 5 | 71.4 |

| Hospital size (no. of beds) | |||

| ≥ 501 | 13 | 8 | 61.5 |

| 201–500 | 33 | 18 | 54.5 |

| ≤ 200 | 26 | 20 | 76.9 |

| Total | 72 | 46 | 63.9 |

*criteria according to NHSN definitions

For the patient-level analysis, there were 871 CRE cases and 727 CSE cases (Table 3). Blood was the most common specimen type for both CRE cases (47.0%) and CSE cases (33.8%), but CRE was more likely among blood specimens compared to other specimen types (respiratory: OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.5–0.85; urine: OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.44–0.8; tissue/wound: OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.39–0.66). The most common pathogen for CRE cases was Klebsiella (85.1%), followed by E. coli (10.2%) and Enterobacter 4.7%. The median age of CRE cases was 19 years compared to that of CSE cases at 37 years (OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.79–0.97).

Most CRE cases were reported from general (n = 248, 28.5%) or obstetrical hospitals (n = 234, 26.9%). The univariate analysis showed that carbapenem resistance was more common among cases admitted to an obstetrical hospital (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.12–1.82), a smaller sized hospital with ≤200 beds (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.57–2.68), a medical/surgical critical care (CC) unit (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.09–2.31), a NICU (OR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.66–3.01), and a pediatric cardiothoracic CC unit (OR = 5.77, 95% CI = 1.66–20.05) [Table 3]. The majority of both CRE cases (75.9%) and CSE cases (70.0%) were hospitalized immediately prior to ICU admission. However, CRE cases were more likely to be hospitalized prior to ICU admission (OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.1–1.68) and have a longer ICU length of stay prior to infection (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.1–2.1).

Table 3.

Analysis of risk factors associated with CR and Non-CR cases

| Characteristics | Total Enterobacteriaceae HAI cases(N = 1598) n % | CRE cases (N = 871) n % | CSE cases (N = 727) n % | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen Type | < 0.001a | |||||||

| Blood | 655 | 41.0 | 409 | 47.0 | 246 | 33.8 | Reference | |

| Respiratory* | 346 | 21.7 | 180 | 20.7 | 166 | 22.8 | 0.65 (0.5–0.85) | 0.001b |

| Urine | 236 | 14.8 | 117 | 13.4 | 119 | 16.4 | 0.59 (0.44–0.8) | 0.001 b |

| Tissue or Wound | 361 | 22.6 | 165 | 18.9 | 196 | 27.0 | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | 0.001 b |

| Type of Enterobacteriaceae Pathogen | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| Klebsiella | 1177 | 73.7 | 741 | 85.1 | 436 | 60.0 | Reference | |

| Enterobacter | 78 | 4.9 | 41 | 4.7 | 37 | 5.1 | 0.65 (0.41–1.03) | 0.068 b |

| E-coli | 343 | 21.5 | 89 | 10.2 | 254 | 34.9 | 0.21 (0.16–0.27) | < 0.00 b |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 28 (1–58) | 19 (1–55) | 37 (1–61) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) | 0.007 a | |||

| Patient Sex | 0.4 a | |||||||

| Male | 859 | 53.7 | 475 | 54.5 | 384 | 52.8 | Reference | |

| Female | 739 | 46.3 | 396 | 45.5 | 343 | 47.2 | 1.07 (0.88–1.31) | |

| Hospital Type | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| General | 433 | 27.1 | 248 | 28.5 | 185 | 25.5 | Reference | |

| Medical | 242 | 15.1 | 109 | 12.5 | 133 | 18.3 | 0.61 (0.45–0.84) | 0.002 b |

| Obstetrics | 362 | 22.7 | 234 | 26.9 | 128 | 17.6 | 1.36 (1.12–1.82) | 0.03 b |

| Pediatrics | 208 | 13.0 | 126 | 14.5 | 82 | 11.3 | 1.15 (0.82–1.61) | 0.42 b |

| Surgical | 353 | 22.1 | 154 | 17.7 | 199 | 27.4 | 0.58 (0.43–0.77) | 0.001 b |

| Hospital Size | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| > =501 | 630 | 39.4 | 317 | 36.4 | 313 | 43.1 | Reference | |

| 201–500 | 602 | 37.7 | 307 | 35.3 | 295 | 40.6 | 1.03 (0.82–1.28) | 0.81 b |

| < =200 | 366 | 22.9 | 247 | 28.4 | 119 | 16.4 | 2.05 (1.57–2.68) | 0.001 b |

| ICU Category | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| Surgical CC | 335 | 21.0 | 166 | 19.1 | 169 | 23.3 | Reference | |

| Burn CC | 54 | 3.4 | 13 | 1.5 | 41 | 5.6 | 0.32 (0.17–0.62) | 0.001 b |

| Medical CC | 50 | 3.1 | 26 | 3.0 | 24 | 3.3 | 1.1 (0.61–2) | 0.75 b |

| Medical CC | 160 | 10.0 | 69 | 7.9 | 91 | 12.5 | 0.77 (0.53–1.13) | 0.18 b |

| Medical Neurological Care | 26 | 1.6 | 9 | 1.0 | 17 | 2.3 | 0.54 (0.23–1.24) | 0.15 b |

| Medical/Surgical CC | 169 | 10.6 | 103 | 11.8 | 66 | 9.1 | 1.59 (1.09–2.31) | 0.01 b |

| NICU | 419 | 26.2 | 288 | 33.1 | 131 | 18.0 | 2.24 (1.66–3.01) | 0.001 b |

| Neurosurgical Critical Care | 101 | 6.3 | 48 | 5.5 | 53 | 7.3 | 0.92 (0.59–1.44) | 0.72 b |

| Ped. Medical Critical Care | 77 | 4.8 | 40 | 4.6 | 37 | 5.1 | 1.1 (0.67–1.81) | 0.71 b |

| Pediatric Cardiothoracic CC | 20 | 1.3 | 17 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.4 | 5.77 (1.66–20.05) | 0.006 b |

| Prenatal/Surgical | 33 | 2.1 | 15 | 1.7 | 18 | 2.5 | 0.85 (0.41–1.74) | 0.65 b |

| Respiratory CC | 44 | 2.8 | 25 | 2.9 | 19 | 2.6 | 1.34 (0.71–2.52) | 0.36 b |

| Surgical Cardiothoracic CC | 29 | 1.8 | 8 | 0.9 | 21 | 2.9 | 0.39 (0.17–0.9) | 0.02 b |

| Trauma CC | 81 | 5.1 | 44 | 5.1 | 37 | 5.1 | 1.21 (0.74–1.97) | 0.44 b |

| Hospitalized prior to ICU admission | 0.008 a | |||||||

| No | 428 | 26.8 | 210 | 24.1 | 218 | 30.0 | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.170 | 73.2 | 661 | 75.9 | 509 | 70.0 | 1.35 (1.1–1.68) | |

| Surgical Procedure during hospital admission | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| No | 972 | 60.8 | 561 | 64.4 | 411 | 56.5 | Reference | |

| Yes | 626 | 39.2 | 310 | 35.6 | 316 | 43.5 | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||||||

| No | 713 | 44.6 | 377 | 43.3 | 336 | 46.2 | Reference | 0.08a |

| Yes | 885 | 55.4 | 494 | 56.7 | 391 | 53.8 | 1.13 (0.92–1.37) | |

| Urinary Catheter | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| No | 579 | 36.2 | 374 | 42.9 | 205 | 28.2 | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.019 | 63.8 | 497 | 57.1 | 522 | 71.8 | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) | |

| Central Line | 0.89 a | |||||||

| No | 537 | 33.6 | 294 | 33.7 | 243 | 33.4 | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.061 | 66.4 | 577 | 66.3 | 484 | 66.6 | 0.99 (0.8–1.21) | |

| LOS in ICU prior to specimen collection, median, days, (IQR) | 7 (3–13) | 8 (3–15) | 5 (2–11) | 1.31 (1.1–2.1) | < 0.001 a | |||

| Patient outcome | < 0.001 a | |||||||

| Discharged/ Transferred | 690 | 43.2 | 339 | 38.9 | 351 | 48.3 | Reference | |

| Died | 908 | 56.8 | 532 | 61.1 | 376 | 51.7 | 1.46 (1.2–1.79) | |

a p-value generated using chi-square test or 2-tailed Fisher Exact test for categorical variables and Student t test or Mann–Whitney test, dependent on the validity of normality assumption for continuous variables

b p-values generated using the logistic regression for specific categories of non-dichotomous variables

c Include: Deep Tracheal Aspirate & BAL: Broncho alveolar lavage

d includes both hospital where Enterobacteriaceae HAI occurred and other hospitals

CRE cases were less likely to have underwent a surgical procedure (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.59–0.88) or had a urinary catheter during the hospital admission (OR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.42–0.64), but there was no significant difference between CRE and CSE cases with respect to mechanical ventilation or central lines. Mortality was also higher among CRE cases than CSE cases (OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.2–1.79). When adjusted for patient and specimen characteristics, the multi-variate analysis showed that hospitalization immediately prior to ICU admission (OR = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.18–1.76; p-value 0.008) and a longer ICU stay prior to specimen collection (OR = 1.08; 95% CI: 1.14–1.36; p-value 0.03) remained significantly associated with carbapenem resistance, while infection with E. coli (OR = 0.22; 95% CI: 0.17–0.3; p-value < 0.001) and identification in a wound specimen (OR = 0.67; 95%CI: 0.5–0.89; p-value 0.01) were associated with not having carbapenem resistance. The association between carbapenem resistance and specific hospital or ICU types did not remain significant in the multivariable analysis.

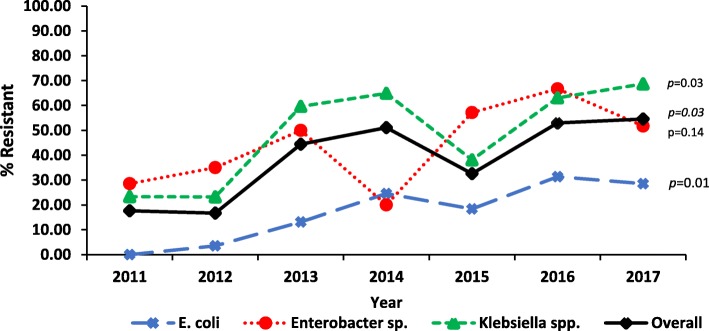

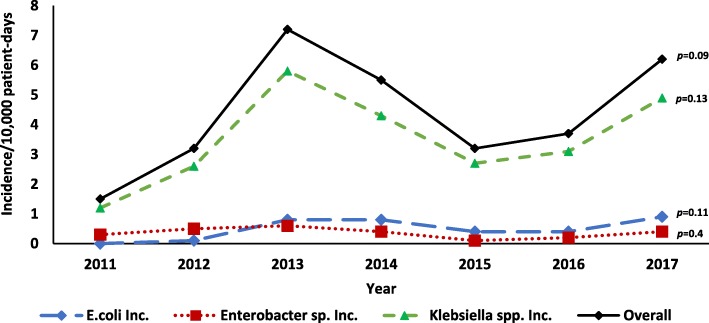

There was an overall increase in the proportion of cases that were CRE (17.6 to 54.6%, p = 0.003), which remained when stratified by pathogen (Fig. 1). Although not statistically significant, the incidence of carbapenem resistance cases for all pathogens increased between 2011 and 2013, followed by a decline between 2013 and 2015. Since 2015, the incidence overall and for each pathogen has again been increasing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of Enterobacteriaceae isolates with Carbapenem resistance by year 2011–2017

Fig. 2.

Incidence of Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections per 10,000 patient-days by year 2011–2017

Discussion

Our analysis found that carbapenem resistance is widespread and the prevalence is increasing in Egypt. We found that more than half of hospitals (64%) had at least one CRE isolate and half (47.9%) of Enterobacteriaceae isolates were CRE, which is higher than estimates reported from other Arab, African, or Asian countries [23–26]. The incidence of CRE HAI (3.7/10,000 patient-days) is also much higher than the overall incidence of all CRE (HAI and non-HAI) reported from other countries, including the United States (0.1–0.4/10,000 patient-days) Canada (0.2 per 10,000 patient-days), and China (0.4 per 10,000 patient-days) [27–29].

The severity of the CRE problem in Egypt emphasizes the importance of healthcare facilities’ to implement CRE prevention and control efforts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO have developed guidance for healthcare facilities on strategies proven to be effective for limiting CRE transmission, including IPC, antimicrobial stewardship, and CRE surveillance [29, 30]. Data from this analysis can be used to guide how and where these strategies can be most efficiently implemented in Egypt.

Potential causes of the high prevalence of CREs in several hospitals in Egypt might be due to the limitation in implementing stewardship programs and IPC measures. IPC activities are a critical part of preventing healthcare-related CRE transmission and include practices such as hand hygiene, minimizing device use, environmental cleaning, and isolation through contact precautions and improve cohorting of patients or staff. Multivariate analysis did not identify specific types of hospitals or ICUs with higher likelihood of carbapenem resistance, which would help target IPC interventions. Rapid identification and reporting of CRE in clinical labs may help to demonstrate where to target prevention efforts in the future.

Previous global studies have found that CRE is associated with increased length of ICU stay, undergoing surgical procedures, and use of medical devices, specifically mechanical ventilation and central venous catheters [9, 33–35]. Our multivariable analysis did not find that carbapenem resistance was significantly associated with exposure to medical devices or surgical procedures. This may be explained by the very high frequency of invasive devices used in Egyptian ICUs, among both CRE and CSE cases. However, this finding should not discount the importance of CRE prevention strategies focused on reducing healthcare exposures, such as device utilization.

We identified a relative decrease in CRE incidence and proportion of carbapenem resistance in 2014–2015. The introduction of an analytic tool in 2013 may have contributed to the reduction in CRE incidence by providing more timely data feedback to hospitals for guiding IPC interventions. The high frequency of CR found in blood and the increased odds of carbapenem resistance among blood may reflect culturing practices, where blood cultures may only be ordered for very ill patients with resistant infections refractory to treatment.

The ability to adequately contain CRE requires sufficient microbiology laboratory testing to ensure accurate CRE detection and timely notification of laboratory results. In this surveillance system, some of the best laboratories in the country are included; the burden and epidemiology in other facilities, particularly those without reliable susceptibility testing, is largely unknown. Although global guidance recommends active surveillance by conducting CRE screening of patients in some situations with an outbreak or ongoing high prevalence of CRE, this practice is not routine in Egypt, and further efforts to implement such activities are likely needed.

The limited number of studies published about CRE in Egypt have involved few facilities and focused mainly on identifying genetic resistance mechanisms, rather than epidemiological risk factors [36–38]. This study uses data from many healthcare facilities across Egypt, thereby strengthening evidence about epidemiological risk factors associated with CRE. While there are different types and sizes of healthcare facilities included, they are a convenience sample and do not constitute a representative sample of the country.

Detection of CRE in this network was also limited by inconsistent microbiology and surveillance capacity at hospital laboratories. Some isolates were not tested for carbapenem susceptibility at the hospital laboratory or were not sent to the AMR reference laboratory for confirmatory testing, resulting in data for these samples not being included in the data analysis. Because active screening for CRE was not being performed, the variable propensity for clinicians to test patients also likely impacted CRE detection. The trend analysis does not take into account changes at the national, facility, or ward level which impact CRE detection, including changes in specimen collection and testing.

The scope of this surveillance system is limited to ICU locations since ICUs are expected to have both the highest risk for transmission and the most vulnerable population. Therefore, this data cannot be used to draw any conclusions about CRE burden or risk factors in non-ICU wards or the community. This surveillance system did not collect data on clinical variables which prior studies have found to be associated with CRE infections, such as patients’ comorbid medical conditions or prior antibiotic exposure.

Conclusions

This study shows that CRE is prevalent and increasing in Egyptian hospitals, suggesting the presence of selective pressures and healthcare transmission. Future implementation of evidence-based IPC strategies to prevent CRE transmission, strengthening microbiology capacity and molecular characterization in addition to including antibiotic stewardship programs, are needed to reduce the burden of CRE and optimize patient treatment strategies. CRE surveillance should be strengthened to better track the incidence and prevalence of this pathogen and define the impact of interventions on the burden of this serious, emerging threat.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding/support

Supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID-Egypt), Work Unit 263-T-14-0001.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, U.S. Government, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population, or the Egyptian Universities.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- AST

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

- BSI

Bloodstream infections

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CRE

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- CSE

Carbapenem- susceptible Enterobacteriaceae

- EMR

Eastern Mediterranean Region

- HAI

Healthcare-associated infections

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- NHSN

National Healthcare Safety Network

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PNA

Pneumonia

- SC

Surveillance coordinators

- SSI

Surgical site infections

- USAID

U.S. Agency for International Development

- UTI

Urinary tract infections

- WHO

World Health Organization’s

Authors’ contributions

SK participated in study design, overview the data collection, performed the analysis, wrote the paper. ML review the analysis, wrote the manuscript and oversight manuscript preparation.

GI, MA, SG, AH, SH, JE, MZ, HR and GK participated in data collection. OH overview the data collection and wrote the manuscript. MT conceived and designed the study, review the analysis, wrote the paper and oversight manuscript preparation. All authors contributed and commented on the manuscript and approved the publication of this version and is accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Authors information

Sara Kotb is an epidemiologist in the Division of Global Health Protection, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the Cairo, Egypt Country Office with research interests in healthcare-associated infection surveillance and antimicrobial resistance.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit No. 3, Cairo, as a nonhuman research activity protocol no. 1114. S.K., O.S., and M.T. are contractors of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Organization WH . Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan LK, Weinstein RA. The Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The Impact and Evolution of a Global Menace. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl_1):S28–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qureshi ZA, Paterson DL, Potoski BA, et al. Treatment outcome of bacteremia due to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: superiority of combination antimicrobial regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(4):2108–2113. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06268-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falagas ME, Tansarli GS, Karageorgopoulos DE, Vardakas KZ. Deaths attributable to Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7):1170–1175. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.121004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Chen G, Wu X, Wang L, Cai J, Chan EW, Chen S, Zhang R. Increased prevalence of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae in hospital setting due to cross-species transmission of the blaNDM-1 element and clonal spread of progenitor resistant strains. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:595. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elbadawi LI, Borlaug G, Gundlach KM, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae transmission in health care facilities — Wisconsin, February–may 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:906–909. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6534a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE THREATS in the United States, 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(MMWR CDC) Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), March 8, 2013 / 62(09);165–170, On March 5, this report was posted as an MMWR Early Release on the MMWR website (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ling ML, Tee YM, Tan SG, et al. Risk factors for acquisition of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae in an acute tertiary care hospital in Singapore. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:26. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q, Zhang Y, Yao X, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae nosocomial infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(10):1679–1689. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kofteridis DP, Valachis A, Dimopoulou D, et al. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection/colonization: a case-case–control study. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vardakas KZ, Matthaioud DK, Falagas ME, Antypa E, Kotelie A. Eleni Antoniadou: Characteristics, risk factors and outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the intensive care unit. J Infect. 2015;70(6):592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seale AC, Gordon NC, Islam J, Peacock SJ, JAG S. AMR Surveillance in low and middle-income settings - A roadmap for participation in the Global Antimicrobial Surveillance System (GLASS) Wellcome Open Res. 2017;2:92. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.12527.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See I, Lessa F. Incidence and pathogen distribution of healthcare-associated infections in pilot hospitals in Egypt. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:1281–1288. doi: 10.1086/673985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talaat M, et al. National surveillance of health care–associated infections in Egypt: developing a sustainable program in a resource-limited country. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.04.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network . Surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Patient Safety Component Manual. Multidrug-Resistant Organism & Clostridioides difficile Infection (MDRO/CDI) Module. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/12pscMDRO_CDADcurrent.pdf.

- 18.Weiner LM, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1288–1301. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-fifth CLSI supplement M100-S25. Wayne (PA): Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

- 20.Patient Safety Component Manual NHSN. 15. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.A. M, Edwards JR, Allen-Bridson K, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2013, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(3):206–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moghnieh RA, Kanafani ZA, et al. Epidemiology of common resistant bacterial pathogens in the countries of the Arab League. Lancet. 2018; Published online October 3, 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30414-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Xu Y, Gu B, Hunag M, Liu H, Xu T, Xia W, et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:376–385. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.12.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitgang EA, Hartley DM, Malchione MD, Koch M, Goodman JL. Review and mapping of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Africa: using diverse data to inform surveillance gaps. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(3):372–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ssekatawa K, Byarugaba DK, Wampande E, Ejobi F. A systematic review: the current status of carbapenem resistance in East Africa. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):629. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3738-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thaden JT, Lewis SS, Hazen KC, et al. Rising rates of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in community hospitals: A mixed-methods review of epidemiology and microbiology practices in a network of community hospitals in the southeastern United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(8):978–983. doi: 10.1086/677157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan BM, Coyle JR, Marchaim D, et al. Statewide surveillance of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Michigan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:342–349. doi: 10.1086/675611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mataseje LF, Abdesselam K, Vachon J, et al. Results from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program on Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae, 2010 to 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6787–6794. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01359-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). November 2015 Update - CRE Toolkit In: National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, editors. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015.

- 31.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259462. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed]

- 32.Zhang Y, Wang Q, Yin Y, Chen H, Jin L, et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem -resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections : report from China CRE network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017. 10.1128/AAC.01882-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Correa L, Martino MDV, Siqueira I, et al. A hospital-based matched case–control study to identify clinical outcome and risk factors associated with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sopirala M, Ssali F, Liao S, Simbartl L, Kralovic S. Risk Factor and Outcome Evaluation in Patients With Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Mid-Western Tertiary Care Academic Medical Center. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(suppl_1):334. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw172.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MuralidharVarmaa L, RohitReddya V, SudhaVidyasagara, AvinashHollaa Nanda KrishnaBhata Risk factors for carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a teritiary hospital—A case control study Indian. J Med Spec. 2018;9(4):178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.injms.2018.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moemen D, Doaa T. Masallat: Prevalence and characterization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from intensive care units of Mansoura University hospitals Egyptian. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2017;4:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 37.ElMahallawy HA, Zafer MM, Amin MA, Ragab MM, Al-Agamy MH. Spread of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae at tertiary care cancer hospital in Egypt. Infect Dis. 2018;50(7):560–564. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2018.1428824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Sweify MA, Gomaa NI, El-Maraghy NN, Mohamed HA. Phenotypic detection of carbapenem resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae in Suez Canal university hospitals, Ismailiya. Egypt Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4:10–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.