Abstract

Introduction

Neisseria elongata, which is part of the normal oropharyngeal bacterial flora, can be an aggressive organism causing serious infections including infective endocarditis. N. elongata infective endocarditis is rare and no current guidelines exist to direct antibiotic selection and/or duration of treatment.

Case report

We report a case of infective endocarditis due to N. elongata and a review of the literature. Our patient is a healthy young woman, who was found to have an aortic root abscess with valve perforation requiring valve replacement.

Discussion

N. elongata infective endocarditis typically affects the left cardiac chambers and is associated with high risk of embolization. A transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed as part of the initial workup to assess the extent of infection, as a high percentage of patients develop perivalvular abscess formation and/or valve perforation. Most patients require prolonged antibiotic therapy and early surgical intervention.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates the potential severity of N. elongata endocarditis. Further studies are needed to establish management guidance.

Keywords: Endocarditis, aortic valve, Neisseria elongata, Gram-negative bacterial infection

Introduction

Neisseria elongata is an aerobic Gram-negative organism. While ordinally a commensal organism of the human oropharyngeal flora, it has been recognized lately as an important pathogen responsible for serious infections including infective endocarditis (IE).1

Endocarditis secondary to non-gonococcal, non-meningococcal Neisseriae such as N. elongata is rare, but may cause serious complications including perivalvular abscess, systemic embolization and congestive heart failure.1,2

Preexisting valve conditions including prosthetic valves, mitral valve prolapse, and bicuspid aortic stenosis were seen in most patients, but normal valves can be affected as well.2

A high index of suspicion is essential to make the diagnosis early and to guide treatment.3

We report a case of N. elongata native valve endocarditis complicated by an aortic root abscess in a patient who was found to have a bicuspid aortic valve, and review the relevant literature.

Case report

A 31-year-old woman with no known comorbidities presented to the Emergency Department for evaluation of intermittent fevers and chills of one-week duration, with associated headache, fatigue and anorexia. She described her headache as dull constant pain across her forehead. She denied any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or urinary symptoms. She had no recent travel or sick contacts.

Physical examination revealed a young woman in no distress. She was febrile with a temperature of 39.4 °C (102.9 °F), tachycardic with a heart rate of 120 beats/min, otherwise hemodynamically stable with a normal respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min and a normal blood pressure of 130/72 mmHg. Her mucous membranes were moist, her neck was supple with no lymphadenopathy, her skin exam did not show any rash or lesions, her heart exam did not reveal any murmurs, and her lung and abdominal exam was unremarkable.

Laboratory tests revealed normal white cell count without leukocytosis, mild anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11 g/dL, thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 86 thousand/microliter, and mild elevation of ALT at 92 units/L and AST at 78 units/L with normal bilirubin level. Renal function and electrolytes levels were normal. Multiplex respiratory virus PCR which assessed for the presence of certain viruses including influenza A and B, adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza viruses, rhinovirus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial viruses was negative, as well as mononucleosis screen test. Chest X-ray was normal. Two sets of blood cultures were obtained on admission, and the patient was admitted to the hospital for close monitoring with a presumed diagnosis of a viral illness. The patient was discharged home the next day.

One day later, she was readmitted for further evaluation as both sets of blood culture were growing rod-shaped Gram-negative organisms and were identified on the following day as Neisseria elongata. The patient was started on ceftriaxone 2 g intravenously daily. She was noted to have a new diastolic murmur grade 2/6, best heard at the left sternal border, otherwise, no signs of endocarditis on her physical exam.

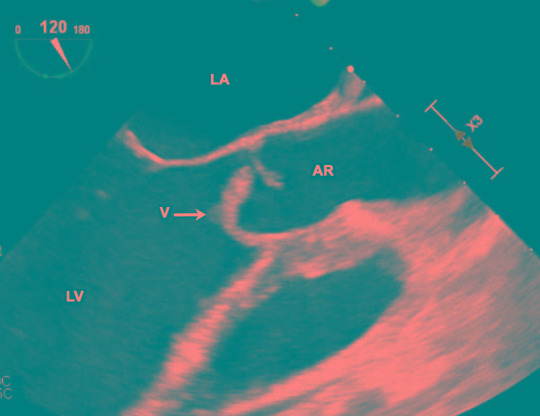

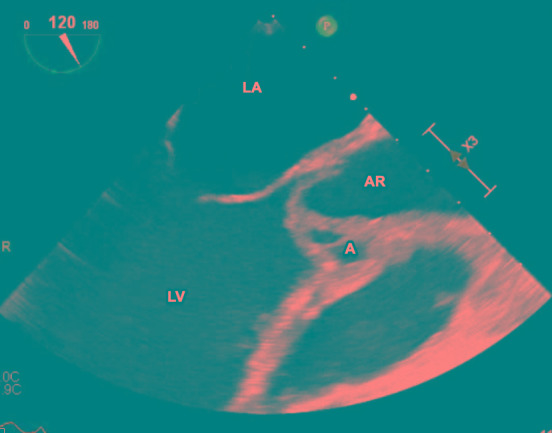

Initial surface echocardiography showed a bicuspid aortic valve with thickening of the right cusp and a small nodule suspicious for a vegetation, with mild eccentric aortic regurgitation. Transesophageal echocardiography (Figure 1) redemonstrated the bicuspid aortic valve, but with a large mobile echogenic mass measuring 1.6 cm on the right coronary cusp, with severe aortic regurgitation, an aortic root abscess (Figure 2), and evidence of right coronary leaflet prolapse into the left ventricle with associated perforation.

Figure 1. Transesophageal echocardiogram, showing the vegetation on the aortic valve. AR – aortic root; LV – left ventricle; LA – left atrium; V – vegetation.

Figure 2. Transesophageal echocardiogram, showing the aortic root abscess. A – abscess; AR – aortic root; LV – left ventricle; LA – left atrium; V – vegetation.

On hospital day 6 of readmission, the patient underwent aortic valve replacement using a 21 mm bovine pericardial bioprosthetic valve. Pathology exam showed fragments of aortic valve showing acute inflammatory infiltrate.

The patient cleared her bacteremia on the third day of appropriate antibiotics, but the excised valve and swabs from the abscess grew N. elongata within 48 hours.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed. Minimum inhibitory concentrations were as follows: penicillin G ≥4 mcg/mL; ceftriaxone 2 mcg/mL; ceftazidime 8 mcg/mL; ciprofloxacin ≤0.12 mcg/mL; and gentamicin ≤0.25 mcg/mL. The strain did not produce β-lactamase.

The patient was treated with a combination of ceftriaxone 2 g daily and ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice daily with plans for a total of 6 weeks from the surgery day, but she developed neutropenia secondary to ceftriaxone on week 3 of therapy; as a result, she was continued on ciprofloxacin orally alone and completed the treatment as an outpatient with resolution of her neutropenia.

To date, six months after the completion of antibiotics, the patient remains afebrile and doing well clinically with no evidence of infection recurrence. The plan is to obtain an echocardiography in the next few months. The search for a primary site of infection remained negative as the patient had no dental infection or sinusitis, and no recent dental procedures.

Review of the literature

We reviewed PubMed for cases of N. elongata endocarditis using appropriate keywords including: endocarditis, aortic valve, Neisseria elongata, Gram-negative bacterial infection. The articles were reviewed to gather information about patients' demographics, preexisting heart diseases, and treatment options. These cases, including the present case, fulfilled the modified Duke criteria for definitive diagnosis of infective endocarditis.

A total of twenty-four reported cases were identified. Including our patient, we analyzed a total of twenty-five cases with a summary of the clinical features in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the clinical features of Neisseria elongata endocarditis.

| Characteristics | Patients (N=25) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | <10 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 61-70 71-80 81-90 |

1 0 5 5 3 4 3 3 1 |

| Preexisting heart disease | Mitral valve prolapse Prosthetic aortic valve Bicuspid aortic valve Rheumatic heart disease Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HOCM) Myxomatous mitral valve Ventricular septal defect None |

4 4 3 1 1 1 1 10 |

| Prior dental infection or treatment | 10 | |

| Murmur | At presentation During illness |

10 16 |

| Valvular Involvement | Aortic Mitral Tricuspid Unknown |

12 10 1 2 |

| Complications | Congestive heart failure (CHF) Abscess formation Systemic embolism Splenic infarction Brachial pseudoaneurysm |

7 5 5 1 1 |

| Treatment | Antibiotics with surgery (%) Antibiotics alone (%) |

15 (60) 10 (40) |

| Surgery | Aortic valve replacement (AVR) Mitral valve replacement (MVR) Debridement of mitral valve Removal of brachial pseudoaneurysm |

8 5 1 1 |

| Antibiotic therapy* | Ceftriaxone Ampicillin and gentamicin Ceftazidime and gentamicin Ceftriaxone and gentamicin Penicillin G and gentamicin Ciprofloxacin Ampicillin Ampicillin and tobramycin Ampicillin and ceftriaxone Ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin Vancomycin Not specified |

5 5 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | 6 weeks 7 weeks 5 weeks 4 weeks 2 weeks 9 weeks Not specified |

7 4 3 3 2 1 5 |

Several antibiotics were used for many of these patients. This table only includes the ones ultimately used at discharge.

Preexisting heart disease was present in 15 patients (60%) with mitral valve prolapse, prosthetic aortic valve, and bicuspid aortic valve representing the majority.

The aortic and mitral valves were the two most common valves affected by Neisseria elongata, with 12 cases (48%) documenting involvement of the aortic valve, and 10 cases (40%) of the mitral valve.

Surgery was required in 15 out of 25 patients (60%), with congestive heart failure, abscess formation and systemic embolism being the most common indications for surgery.

Discussion

The patient had N. elongata subsp elongata endocarditis as defied by the modified Duke criteria.4

N. elongata is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped commensal bacterium with an optimal growth temperature at 35 degrees Celsius. It was first described by Bovre and Holten in 1970.5

It represents normal oropharyngeal flora. There are three subspecies including N. elongata subsp nitroreducens, N. elongata subsp elongata, and N. elongata subsp glycolytica.6 This classification is based on the biochemical differences between each subspecies. N. elongata subsp. nitroreducens is different from N. elongata subsp. elongata and N. elongata subsp. glycolytica in its ability to reduce nitrate. N. elongata subsp. glycolytica differs from the other subspecies based on its feature of testing positive for catalase. N. elongata subsp. elongata differs from the other two subspecies due to its inability to produce acid from D-glucose.6

Endocarditis caused by non-pathogenic Neisseriae, meaning non-gonococcal, non-meningococcal Neisseriae, has been increasingly reported in recent decades.3,7 Preexisting heart diseases (valvular or congenital heart disease) are the primary risk factors for N. elongata endocarditis including our case who had bicuspid aortic valve.8 Endocarditis due to these saprophytic Neisseriae usually results in an acute febrile illness and a large vegetation. Disease is often destructive, associated with severe complications, especially systemic embolism and perivalvular abscesses.1,3

In our case, the patient presented with acute endocarditis with a large mobile mass, associating with severe aortic regurgitation, an aortic root abscess and an associated perforation.

The valve destruction was considered to have been induced by N. elongata.

Delay in diagnosis is mainly due either to absence of a murmur at presentation, or to difficulty in identifying the organism.3 No guidelines exist to direct the antibiotic choice or duration for treatment of N. elongata endocarditis. Detailed susceptibility profile testing is required as N. elongata demonstrates a reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone, as with our patient, and variable sensitivities to penicillin and trimethoprim. Otherwise, the organism is usually susceptible to amoxicillin, gentamicin and ciprofloxacin.9

A previous study has shown that ciprofloxacin can be a great oral option for treatment of N. elongata endocarditis given its excellent bioavailability.10

Furthermore, the review of the literature including our case suggest that endocarditis caused by N. elongata requires surgical intervention.

Conclusions

We conclude that N. elongata, previously considered nonpathogenic, can be a causative agent of infective endocarditis mostly affecting young adults with underlying valvular disease. These data underline the need for a prompt early recognition and treatment of N. elongata endocarditis as, based on the previous literature including our case, the clinical course is often associated with serious complications, especially valve destruction and major embolism. The treatment includes antibiotics as well as surgical intervention in the majority of cases.

Footnotes

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images.

Authors’ contributions statement: All authors have equally contributed to this paper. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: All authors – none to declare.

Funding: None to declare.

References

- 1.Hsiao JF, Lee MH, Chia JH, Ho WJ, Chu JJ, Chu PH. Neisseria elongata endocarditis complicated by brain embolism and abscess. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:376–81. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picu C, Mille C, Popescu GA, Bret L, Prazuck T. Aortic prosthetic endocarditis with Neisseria elongata subspecies nitroreducens. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:280–2. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddow LJ, Mulgrew C, Ansari A, et al. Neisseria elongata endocarditis: case report and literature review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:426–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–8. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bøvre K, Holten E. Neisseria elongata sp. nov., a rod-shaped member of the genus Neisseria. Re-evaluation of cell shape as a criterion in classification. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;60:67–75. doi: 10.1099/00221287-60-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen BM, Weyant RS, Steigerwalt AG, et al. Characterization of Neisseria elongata subsp. glycolytica isolates obtained from human wound specimens and blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:76–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.76-78.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samannodi M, Vakkalanka S, Zhao A, Hocko M. Neisseria elongata endocarditis of a native aortic valve. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213311. pii: bcr2015213311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofstad T, Hope O, Falsen E. Septicaemia with Neisseria elongata ssp. nitroreducens in a patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:200–1. doi: 10.1080/003655498750003672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins JM, Fife A, Baghai M, Dworakowski R. Neisseria elongata subsp elongata infective endocarditis following endurance exercise. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212415. pii: bcr2015212415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbert DA. Successful oral ciprofloxacin therapy of Neisseria elongata endocarditis. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1529–30. doi: 10.1177/1060028014545355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]