Abstract

Objective:

We sought to compare traditional inpatient outcomes to long-term functional outcomes and mortality of surgical intensive care unit patients (SICU) with sepsis.

Summary Background Data:

As inpatient sepsis mortality declines, an increasing number of initial sepsis survivors now progress into a state of chronic critical illness (CCI) and their post-discharge outcomes are unclear.

Methods:

We performed a prospective, longitudinal cohort study of SICU patients with sepsis.

Results:

Among this recent cohort of 301 septic SICU patients, 30-day mortality was 9.6%. Only 13 (4%) patients died within 14 days, primarily of refractory multiple organ failure (62%). The majority (n=189, 63%) exhibited a rapid recovery (RAP), while 99 (33%) developed CCI. CCI patients were older, with greater comorbidities, and more severe and persistent organ dysfunction than RAP patients (all p<0.01). At 12-months, overall cohort performance status was persistently worse than pre-sepsis baseline (WHO/Zubrod score 1.4±0.08 vs 2.2±0.23, p>0.0001) and mortality was 20.9%. Of note at 12 months, the CCI cohort had persistent severely impaired performance status and a much higher mortality (41.4%) than those with RAP (4.8%) after controlling for age and comorbidity burden (Cox hazard ratio 1.27, 95% C.I. 1.14-1.41, p<0.0001). Among CCI patients, independent risk factors for death by 12-months included severity of comorbidities and persistent organ dysfunction (SOFA≥6) at day 14 after sepsis onset.

Conclusion:

There is discordance between low inpatient mortality and poor long-term outcomes after surgical sepsis, especially among older adults, increasing comorbidity burden and patients that develop CCI. This represents important information when discussing expected outcomes of surgical patients who experience a complicated clinical course due to sepsis.

Keywords: sepsis, critical care, multiple organ failure, shock, chronic critical illness

MINI-ABSTRACT

While inpatient mortality after surgical sepsis continues to decline, long-term outcomes after sepsis in surgical patients remains unknown. In this 1-year prospective longitudinal cohort study of SICU patients, we document a surprisingly low early mortality, good outcomes in the majority of those who rapidly recovery, but notably dismal long-term outcomes in the one-third of patients who progress into a clinical trajectory of chronic critical illness.

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis remains one of the largest health care burdens in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence of 1.7 million sepsis cases and annual hospital care costs exceeding U.S. $20 billion dollars.(1) Recent epidemiology studies estimate that sepsis is present in 30% to 50% of hospitalizations that culminate in death.(1, 2) Most of these reports come from medical intensive care units (ICUs), where septic patients often present with severe chronic comorbidities and thus most of theirs deaths are unpreventable.(1) In contrast, surgeons are less likely to operate on these severely debilitated patients and consequently inpatient mortality after surgical sepsis has substantially decreased over the past 15 years as a result of early sepsis screening and reliable implementation of evidence based ICU care.(3, 4) Many patients who previously succumbed to early refractory shock and later multiple organ failure (MOF), now survive their index hospitalization.(5) However, a disturbing number of these “sepsis survivors” develop a clinical trajectory of chronic critical illness (CCI), with a prolonged ICU course, high resource utilization, and persistent but manageable organ dysfunction.(6–8) These patients have an underlying pathophysiologic syndrome of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism (PICS) with evidence of elevated circulating inflammatory biomarkers, innate immune suppression and lean body mass protein catabolism out to 28 days after sepsis onset.(7, 9) Almost all are discharged to high resource post-discharge care facilities that are known to be associated with poor long-term outcomes.(6, 7) The purpose of this report describe the current epidemiology of surgical sepsis in a prospective cohort, specifically to compare traditional in-hospital outcomes to previously poorly documented long-term outcomes.

METHODS

Prospective Study Design

We performed a prospective, observational cohort study with 1-year longitudinal follow-up of surgical intensive care unit (SICU) patients that were admitted with, or subsequently developed sepsis over a 36 month period (ending January 2018) at a quaternary academic medical and Level One trauma center (UF Health - Gainesville, Florida, U.S.A.). Detailed study cohort design and protocols utilized by the University of Florida (UF) Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center (SCIRC) program have been published previously, however key aspects are described below.(10) The purpose of the UF SCIRC program was to define the epidemiology, dysregulated immunity and long-term outcomes of surgical patients that survive the initial physiologic insult of sepsis among critically ill SICU patients. This study was approved by the UF institutional review board and registered with clinicaltrials.gov ().

Overall cohort inclusion criteria included: 1) age ≥18 years; 2) clinical diagnosis of sepsis as defined by 2001 consensus guidelines; and 3) entrance into the electronic medical record (EMR) based sepsis clinical management protocol.(10, 11) Exclusion criteria included of any of the following: 1) refractory shock (death <24 hours from sepsis protocol initiation) or inability to achieve source control (e.g., total bowel ischemic necrosis); 2) pre-admission expected lifespan <3 months; 3) patient/proxy not committed to aggressive management; 4) severe CHF (NYHA Class IV); 5) Child-Pugh Class C liver disease or pre-liver transplant; 6) known HIV with CD4+ count <200 cells/mm3; 7) patients receiving chronic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, including organ transplant recipients; 8) pregnancy; 9) institutionalized patients; 10) inability to obtain informed consent within 96 hours of enrollment; 11) chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 30 days; 12) severe traumatic brain injury (TBI); and 13) spinal cord injury (SCI) resulting in permanent sensory and/or motor deficits. These criteria were selected for the overall program cohort to focus on a population whose baseline immunosuppression, end-stage comorbidities or severe functional injuries (i.e. TBI, SCI, and imminently terminal underlying disease process) would not be the primary determinant of subsequent long-term outcomes. All enrolled subjects underwent prospective clinical adjudication by physician investigators at weekly program adjudication and retention meetings to confirm sepsis diagnosis, severity and source.(10)

Sepsis screening, diagnosis, resuscitation and management was performed and supplemented by EMR based sepsis management protocol to ensure timely and standardized evidenced-based care.(7, 10) Patient demographics, comorbidities, sepsis diagnosis and severity adjudication and clinical outcomes were manually curated in prospective fashion. Additionally, a priori designated clinical data from the EMR related to the index and subsequent hospitalizations were directly uploaded to an analytical database by the UF Health Integrated Data Repository (IDR) for subsequent analyses.

Longitudinal follow-up was performed for one year. Following discharge, patients (or patient proxy) were contacted monthly by telephone to obtain information related to subsequent hospitalizations, and current disposition, including mortality. Among survivors, we completed prospective follow-up assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months after sepsis onset for physical assessments and determination of overall functional status. Patients were scheduled for follow-up visits, which were conducted at the UF Institute on Aging, the patient’s home, or via telephone, as feasible in that sequence of priority.

Definition of Outcomes

The primary inpatient outcome of interest was 30-day mortality. Additional outcomes included ICU length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, length and severity of organ dysfunction, clinical trajectory, secondary infections and discharge disposition. Overall and organ-specific organ dysfunction severity was determined by utilizing sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score.(12) Incidence of MOF was determined by utilizing Denver criteria.(13) Inpatient clinical trajectory was defined as ‘early death’, ‘rapid recovery’ (RAP), or ‘chronic critical illness’ (CCI). Early death is defined as death within 14 days of sepsis onset. CCI is defined as an ICU LOS greater than or equal to 14 days with evidence of persistent organ dysfunction based upon components of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score.(7, 8, 10, 12) Rapid recovery (RAP) patients are those discharged from the ICU within 14 days with resolution of organ dysfunction. Hospital-acquired secondary infections were adjudicated by the investigators utilizing current United States Centers for Disease Control definitions and guidelines. Discharge disposition was classified based on known associations with long-term outcomes as either ‘good’ (Home with or without health care services, or rehabilitation facility) or ‘poor’ (Long-term acute care facility [LTAC]), skilled nursing facility [SNF], another acute care hospital, hospice or inpatient death).

The primary long-term outcome of interest was mortality at 12 months. Additional long-term outcomes included physical function and performance status. Physical function was measured by administration of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), an objective assessment tool for evaluating lower extremity function.(10) Performance status was measured by WHO/Zubrod score, a 6-point scale that measures the performance status of a patient’s ambulatory nature. Zubrod score range is from zero to five, with increasing score reflecting worse performance status: (0) Asymptomatic (fully active), (1) Symptomatic but completely ambulatory (restricted in physically strenuous activity), (2) Symptomatic, <50% in bed during the day (ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to perform any work activities), (3) Symptomatic, >50% in bed, but not bedbound (capable of only limited self-care), (4) Bedbound (completely disabled, incapable of any self-care), and (5) Death.(10) Baseline (i.e., pre-hospitalization) performance status was based upon patient/proxy reported 4-week recall assessment as soon as possible after sepsis onset.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as frequency and percentage, mean and standard deviation, or median and 25th/75th percentiles. Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for comparison of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The number of secondary infections per 100 hospital person days was modeled using a Poisson rate model with overdispersion, while the number of secondary infections per patient was modeled using a Poisson model with overdispersion. For age-based mortality analysis, patients were classified as either young (age ≤45 years), middle-aged (46-64 years), or older adults (age ≥65 years) as commonly defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA). The log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates of survival between groups. This included comparison of 12-month mortality between CCI and RAP groups included controlling for age and comorbidity burden as measured by Charlson comorbidity index total score. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression models were utilized to determine independent early risk factors (determinable by 72 hours of sepsis onset) for the development of CCI, as well as independent risk factors at 14 days predictive of death by 12-months. Variables included for model selection were based upon statistical significance on univariate analysis and clinical relevancy and are listed in the legend of Table 5. Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine optimal dichotomous cutoffs for SOFA scores during model development. All significance tests were two-sided, with p-value ≤0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC; U.S.A.).

Table 5.

Multivariate prediction models for CCI and 12-month mortality

| Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 72 Hour model - CCI or Early death1 | |||

| Max. SOFA ≥5 | 5.46 | (2.98-9.99) | <0.0001 |

| Inter-facility hospital transfer | 3.24 | (1.79-5.84) | <0.0001 |

| Septic Shock | 2.20 | (1.13-4.29) | 0.021 |

| AKI - KDIGO Stage 3 | 4.80 | (1.81-12.69) | 0.0016 |

| 14 day model - CCI patient 12-month mortality2 | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index score | 1.33 | (1.07-1.66) | 0.011 |

| SOFA ≥6 at day 14 | 4.62 | (1.54-13.8) | 0.0062 |

Covariates for 72 –hour model selection included age, Charlson comorbidity score, total SOFA≥5 at 72 hours, transfer status, septic shock, sex, and KDIGO stage 3 acute kidney injury. (Model AUC=0.812)

Covariates for 14 day model selection included age, Charlson comorbidity score, total SOFA≥6 at day 14, KDIGO stage 3 acute kidney injury and diagnosis of active malignancy. (Model AUC=0.759)

RESULTS

Sepsis cohort demographics

Over a period of 36 months we screened 1,908 suspected patient sepsis events and subsequently enrolled 301 consecutive critically ill SICU patients with sepsis into the study cohort (see CONSORT diagram; Supplemental Digital Content 1). The overall study population consisted primarily of middle-aged and older adults, with a moderate comorbidity burden (Table 1). Ninety patients (30%) carried an active diagnosis of malignancy. More than half of enrolled patients were initially admitted on the index hospitalization for elective surgery or a non-surgical medical complication and subsequently developed surgical sepsis requiring admission to a surgical ICU (Table 1). Physiologic derangement within 24 hours of sepsis onset was severe, as reflected by a 26 percent incidence of vasopressor dependent shock and high median APACHE II score (Table 1). The leading adjudicated source of sepsis was intra-abdominal sepsis (40%), followed by pneumonia (17%) and necrotizing soft tissue infection (14%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Overall cohort demographics and 30-day mortality

| Sepsis cohort (n=301) | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 169 (56.1) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 59 (15.3) |

| Young (≤45 yrs), n (%) | 58 (19.3) |

| Middle-aged (46-64 yrs), n (%) | 124 (41.2) |

| Older adults (≥65 yrs), n (%) | 119 (39.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 270 (89.7) |

| African American | 27 (9) |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 3 (1) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (25th, 75th) | 3 (1, 5) |

| Active cancer diagnosis, n (%) | 90 (29.9) |

| Hospital admission diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Non-infectious acute medical condition | 106 (35.2) |

| Planned elective surgery | 59 (19.6) |

| NSTI | 40 (13.2) |

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | 23 (7.6) |

| Trauma | 25 (8.3) |

| SSI | 24 (8.0) |

| UTI | 8 (2.6) |

| Other infectious perioperative complication | 16 (5.3) |

| Inter-facility hospital transfer, n (%) | 120 (39.9) |

| Primary sepsis diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | 121 (40.2) |

| Pneumonia | 51 (16.9) |

| NSTI | 43 (14.3) |

| Surgical Site Infection | 33 (10.9) |

| UTI | 30 (10.0) |

| Empyema | 6 (2.0) |

| Catheter-related bloodstream infection | 3 (1.0) |

| Other | 14 (4.7) |

| Sepsis severity1, n (%) | |

| Sepsis | 92 (30.6) |

| Severe sepsis | 132 (43.9) |

| Septic shock | 77 (25.6) |

| APACHE II, median (25th, 75th) | 17 (12, 23) |

| MOF, n (%) | 146 (48.5) |

| ICU LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 7 (3, 17) |

| Hospital LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 16 (8, 27) |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 29 (9.6) |

Inpatient and 30-day outcomes

Overall incidence of sepsis-associated MOF was high (n=146, 49%; Table 1). Regarding clinical trajectory after sepsis onset, 13 patients (4%) died within 14 days, while 99 (33%) developed CCI and the remaining 189 (63%) exhibited a rapid recovery (Table 2). The primary cause of mortality among early death patients was refractory MOF (62%), with the majority of these deaths (69%) occurring after transitioning to withdrawal of active care (Tables 2 & 4).

Table 2.

Inpatient clinical trajectories and organ dysfunction

| Early Death (n=13; 4%) | CCI (n=99; 33%) | RAP (n=189; 63%) | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 8 (61.5) | 64 (64.6) | 97 (51.3) | 0.034 |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 67.2 (13.1) | 61.8 (14.7) | 56.9 (15.5) | 0.0024 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (25th, 75th) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (2, 5) | 2 (1, 4) | 0.0002 |

| APACHE II, median (25th, 75th) | 29 (21, 38) | 22 (16, 26) | 14 (10, 19) | <0.0001 |

| Inter-facility hospital transfer, n (%) | 8 (61.5) | 53 (53.5) | 59 (31.2) | 0.0003 |

| Septic shock, n (%) | 10 (76.9) | 39 (39.4) | 28 (14.8) | <0.0001 |

| MOF incidence, n (%) | 13 (100) | 78 (78.8) | 55 (29.1) | <0.0001 |

| Maximum SOFA score, median (25th, 75th) | 15 (12, 21) | 10 (8, 12) | 5 (3, 8) | <0.0001 |

| Max. Respiratory SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 4 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | <0.0001 |

| Max. Cardiovascular SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 4 (3, 4) | 3 (1, 4) | 1 (1, 1) | <0.0001 |

| Max. Coagulation SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.0007 |

| Max. CNS SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 4 (4, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 1 (0, 3) | <0.0001 |

| Max. Hepatic SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 2 (1, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.0397 |

| Max. Renal SOFA, median (25th, 75th) | 4 (3, 4) | 2 (0, 4) | 1 (0, 2) | <0.0001 |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 13 (100) | 65 (65.7) | 99 (52.4) | 0.0337 |

| KDIGO Stage 1, n (%) | 0 (0) | 29 (29.3) | 47 (24.9) | 0.4818 |

| KDIGO Stage 2, n (%) | 4 (30.8) | 14 (14.1) | 44 (23.3) | 0.0881 |

| KDIGO Stage 3, n (%) | 9 (69.2) | 22 (22.2) | 8 (4.2) | <0.0001 |

Table 4.

Post-sepsis mortality

| Sepsis cohort (n=301) | |

|---|---|

| Early Death (< 14 days) | 13/301 (4.3%) |

| MOF | 8 (62%) |

| End-stage vascular disease | 3 (23%) |

| Respiratory failure/ARDS | 2 (15%) |

| Involved withdrawal of care | 9/13 (69%) |

| 30-day mortality | 29/301 (9.6%) |

| MOF | 17 (59%) |

| End-stage vascular disease | 4 (14%) |

| Respiratory failure/ARDS | 2 (7%) |

| Heart failure | 1 (3%) |

| Involved withdrawal of care | 23/29 (79%) |

| >30-day mortality (late deaths) | 34/301 (11.3%) |

| Late MOF | 8 (24%) |

| End-stage cancer | 7 (21%) |

| Sepsis (recurrent) | 7 (21%) |

| Heart failure/MI | 5 (15%) |

| End-stage vascular disease | 3 (9%) |

| Renal Failure | 2 (6%) |

| CVA | 2 (6%) |

| Unknown | 2 (6%) |

| Involved withdrawal of care | 18/34 (53%) |

| Overall 12-month mortality | 63/301 (20.9%) |

| Late MOF (not infection related) | 23 (37%) |

| Sepsis (recurrent) | 12 (32%) |

| End-stage cancer | 7 (11%) |

| End-stage vascular disease | 7 (11%) |

| Heart failure/MI | 6 (10%) |

| Respiratory failure | 2 (3%) |

| Renal failure | 2 (3%) |

| CVA | 2 (3%) |

| Unknown | 2 (3%) |

| Involved withdrawal of care | 41/63 (65%) |

Of the patients that survived to day 14 after sepsis onset, patients that developed CCI were significantly older, had a higher burden of chronic comorbidities, and a higher incidence and severity of organ dysfunction than those that rapidly recovered (Table 2). Additionally, CCI patients had a higher number of secondary infections as well as greater consumption of inpatient resources as measured by hospital and ICU length of stay, as compared to those with a trajectory of rapid recovery (Table 3). While eighty-six CCI patients (87%) survived the index hospitalization, nearly all (82%) had a “poor” discharge disposition (i.e., Long-term acute care facility [LTAC], skilled nursing facility [SNF], hospice or inpatient death; Table 3). Independent risk factors at 72 hours after sepsis onset predictive of developing a clinical trajectory of CCI included a maximum SOFA score greater than or equal to five, being received as an inter-facility hospital transfer, persistent vasopressor requirement (i.e., septic shock), and the development of KDIGO Stage 3 kidney injury (Table 5).

Table 3.

Inpatient clinical trajectories and outcomes

| Early Death (n=13; 4%) | CCI (n=99; 33%) | RAP (n=189; 63%) | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Secondary infections, mean per patient (SD) | 0.2 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0.2 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| # Secondary infections per 100 person hospital days, mean (SD) | 2.1 (4.4) | 2.9 (3.1) | 1 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| ICU LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 5 (3, 7) | 21 (15, 29) | 4 (2, 9) | <0.0001 |

| Hospital LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 6 (3, 7) | 28 (20, 42) | 11 (7, 19) | <0.0001 |

| Discharge disposition, n (%) | ||||

| “Good” disposition | 0 (0) | 18 (18.2) | 149 (78.8) | <0.0001 |

| Home | N/A | 1 (1) | 54 (28.6) | |

| Home healthcare services | N/A | 10 (10.1) | 85 (45) | |

| Rehabilitation facility | N/A | 7 (7.1) | 10 (5.3) | |

| “Poor” disposition | 13 (100) | 81 (81.8) | 40 (21.2) | <0.0001 |

| Long Term Acute Care facility | N/A | 41 (41.4) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Skilled Nursing facility | N/A | 11 (11.1) | 35 (18.5) | |

| Another Hospital | N/A | 10 (10.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Hospice | N/A | 6 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Death | 13 (100) | 13 (13.1) | 0 (0) |

Univariate analysis comparing CCI vs RAP groups.

Overall 30-day mortality among sepsis patients within this cohort was 9.6 percent (Table 4). The primary cause of death within 30 days was MOF (59%), followed by end-stage vascular disease (e.g., terminal mesenteric or limb ischemia; 14%), respiratory failure (15%) and heart failure (3%; Table 4). Nearly 80 percent of all deaths within 30 days involved withdrawal of active care and initiation of comfort measures (Table 4).

Long-term outcomes

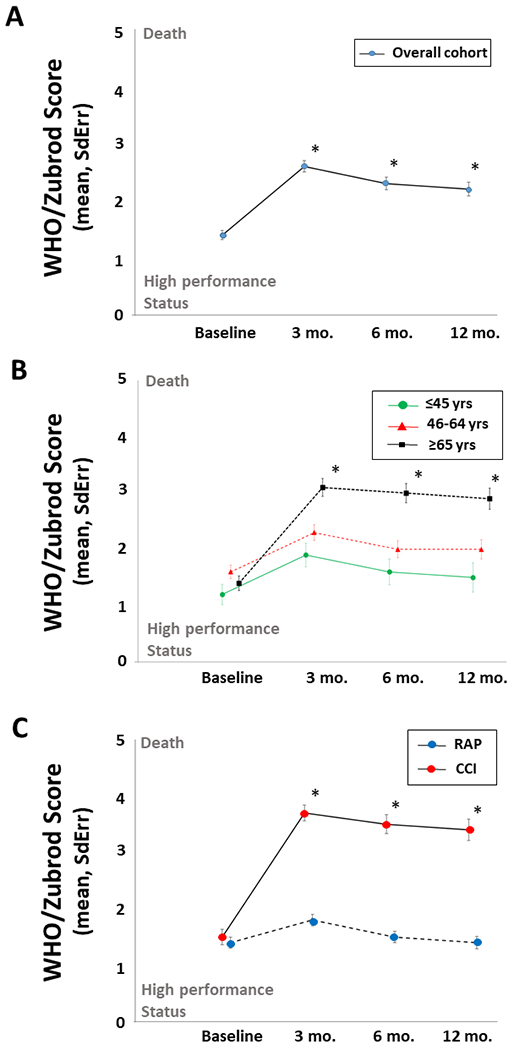

Among all sepsis patients in the cohort there were significant and persistent performance status deficits compared to baseline as measured by WHO/Zubrod score at 3, 6 and 12-months after sepsis onset (Figure 1A). Although similar at pre-sepsis baseline, older adults (≥65 years) had significantly worse performance status as compared to young (≤45 years) or middle-aged (46-64 years) cohorts that persisted out to 12-months after sepsis onset (Figure 1B). The development of an inpatient clinical trajectory of CCI was associated with highly morbid performance status out to 12 months after sepsis onset as compared to those who rapidly recovered (Figure 1C). Additionally, CCI patients had significantly worse physical function as measured by mean SPPB total score at 3 months (2.7±0.76 vs 6.5±0.57; p=0.0001), 6 months (3.2±0.75 vs 6.9±0.62; p=0.0003), and 12-months (3.1±0.87 vs 7.4±0.78; p=0.0005) months after sepsis onset.

Figure 1. Long-term performance status after sepsis.

(A) Long-term performance status over 12-month longitudinal follow-up. Baseline represents self-reported pre-sepsis performance status. *3, 6, and 12-month assessments compared to baseline, p<0.0001. (B) Long-term performance status comparing older (≥65 years), middle-age (46–64 years) and young (≤45 years) adults. *older vs middle-age and older vs young, both p<0.001. (C) Long-term performance status of chronic critical illness (CCI) as compared to rapid recovery (RAP) inpatient clinical trajectories. *CCI vs RAP, p<0.005.

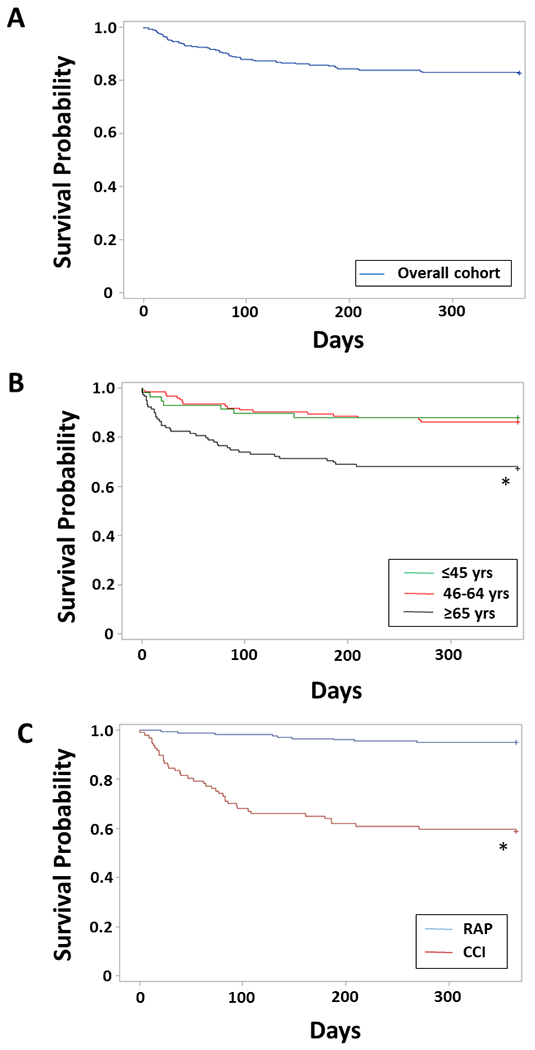

The mortality rate at 12 months for the overall sepsis cohort was more than 2-fold greater than that by hospital discharge (21% vs 9%; Table 1 & Figure 2A). The primary cause of death after 30 days (i.e. ‘late deaths’) were persistent or late onset MOF (24%), end-stage cancer (21%) and recurrent sepsis (21%; Table 4). Over 50 percent of late deaths were in the setting of withdrawal of active care or hospice (Table 4). Older individuals had significantly higher 12-month mortality rate (32.8%) compared to both young (12.1%; p=0.004) and middle-aged (13.7%; p=0.0003) adults (Figure 2B). When comparing inpatient clinical trajectories, septic patients that developed CCI had significantly higher 12-month mortality (n=41/99; 41.4%) than those with rapid recovery (n=9/189; 4.8%) after controlling for age and comorbidity burden (Cox proportional hazard ratio 1.27, 95% C.I. 1.14-1.41, p<0.0001; Figure 2C). Among CCI patients, independent risk factors at day 14 (i.e., CCI onset) found to be predictive for death by 12 months included comorbidity burden (as measured by Charlson comorbidity index) and significant persistent organ dysfunction (total SOFA score ≥6; Table 5). When broken into the six individual SOFA components, hepatic SOFA (Odds ratio 2.65, 95% CI 1.15-6.08, p=0.021) and respiratory SOFA score (Odds ratio 1.64, 95% CI 1.03-2.63, p=0.039) were the only organ specific scores included in the model with total Charlson score (AUC=0.775). Of note, a diagnosis of active malignancy was included as a covariate in the multivariate analysis, but was not found to be an independent predictor of 12-month mortality.

Figure 2. Post-sepsis 12-month survival.

(A) Overall cohort 12-month survival. (B) 12-month survival by older (≥65 years), middle-age (46–64 years) and young (≤45 years) age groups. *older vs middle-age and older vs young, log rank test both p<0.005. (C) 12-month survival comparing CCI to RAP clinical trajectories. *Cox proportional hazard controlling for age and Charlson comorbidity score, p<0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Although 30-day mortality has long been the “gold-standard” of quality and acceptable outcomes among surgery patients, its contemporary relevance has recently come under criticism.(14) Over the past several decades widespread implementation of evidenced based critical care has progressively evolved the traditional “black and white” post-operative outcomes of survival and death into a spectrum of “grey”. This is true in septic patients as well, with emphasis on the Surviving Sepsis Campaign significantly improving in-hospital mortality.(15–18) As a result, many patients now survive to develop a state of chronic critical illness (CCI) with a prolonged hospital and ICU length of stay, persistent but manageable organ dysfunction, and recurrent nosocomial infections.(8, 19) Although most survive to hospital discharge, the vast majority are discharged to LTAC and SNF facilities where they fail to rehabilitate and linger with persistent deficits in physical function.(6, 20) Many suffer from ‘sepsis recidivism’ with frequent hospital readmissions, and the post-discharge and long-term outcomes of these ‘sepsis survivors’ remains incompletely defined.(9, 21)

In this study we have shown a significant discordance between the historic reported 30 day sepsis mortality of 30% to 50% to our contemporary low 30 day mortality of 10%.(22–24) One could argue that our research program’s focus on elucidating the dysfunctional immunophenotype associated with poor long-term outcomes among septic surgical patients led to stringent exclusion criteria that could underestimate overall mortality. However, we were surprised to find that very few (<4% of 1,908 patient sepsis events screened) were excluded due to refractory shock (0.8%), pre-existing limitations of care or DNR status (1.2%) or an expected lifespan less than 3 months (1.3%; SDC 2). Strikingly, overall mortality at 12-months was over twice that at 30 days. Importantly, these discrepancies in outcomes appear to be closely linked to the trajectory of organ dysfunction recovery. Among this cohort of over 300 sepsis patients, less than five percent died within two weeks of sepsis onset. Over half resolved their organ dysfunction and were discharged from the ICU within 14 days, and over ninety percent were alive at 30 days. As alluded to previously, this decrease in early mortality most likely reflects improvements in sepsis screening, resuscitation and advanced organ support. Despite these rather optimistic inpatient survival statistics, one-third of these surgical sepsis patients developed a complicated clinical trajectory of a prolonged ICU stay and persistent but sustainable organ dysfunction (i.e, CCI). Although over 80 percent of CCI patients survived to hospital discharge, this clinical trajectory was strongly predictive of either severe debilitated functional status or death at 1-year.

Given that developing a complicated clinical course of persistent organ dysfunction (i.e., CCI) carries such a high risk of poor long-term outcomes, it is clear that clinicians will need new tools to assist informing patients (or their families/proxies) with accurate prognostic information in order to set treatment goals and expectations and ultimately guide therapeutic decisions. It would be ideal to identify those patients at high risk of developing CCI within the first few days of sepsis onset in order to target individuals that may benefit from early targeted interventions to minimize and/or reverse a trajectory of persistent organ dysfunction. In this study population, we were able to develop a clinical risk factor model with high predictive ability (AUC=0.812) at 72 hours after sepsis onset. Unfortunately, despite extremely promising mechanistic and pre-clinical data, a multitude of previous attempts to utilize immunomodulatory agents to quell the initial “inflammatory storm” of sepsis have failed miserably. It is likely that this failure lies not primarily within the agents themselves, but rather the choice (or lack thereof) of which patients to include in these clinical trials.(25) Significant progress in characterizing and risk stratifying the initial dysfunctional genomic response to severe injury and sepsis, including the development of precision medicine approaches to utilizing predictive genomic metrics.(26–28) However, due to system redundancy and host heterogeneity, attempting to improve outcomes after sepsis by attempting early manipulation of the innate immune response currently remains problematic.

Because of the challenges regarding early therapeutic outcomes targeting dysfunctional inflammation and organ dysfunction after sepsis, it is crucial to understand the natural course of initial sepsis survival and be able to identify who is at high risk of poor long-term outcomes. It is clear in this and previous studies that initial survivors of sepsis are at risk for significant late morbidity and mortality secondary to recurrent infections.(9, 21) This is illustrated in this sepsis cohort as we showed that refractory MOF and recurrent sepsis are the leading causes of long-term mortality. Fortunately, some initial insight exists into the mechanisms of this morbid cycle of “sepsis recidivism”. It has been shown previously that patients that survive the initial septic insult exhibit evidence of persistent immunosuppression, and therefore would be attractive candidates for a newer generation of immune restoring therapies (e.g., anti-programmed death ligand 1 [α-PDL1] and recombinant IL-7).(29, 30) However, the problem for correctly selecting patients likely to respond to a given therapy remains a significant challenge. A combination of clinical prediction models (such as those presented here) and risk stratifying biomarkers (e.g., elevated IL-6, or decreased leukocyte HLA-DR expression) would be ideal to help develop a precision medicine approach and optimize patient selection for randomized controlled trials of these next generation immunomodulatory agents.(9, 30) By restoring immune competency, reducing secondary infections, and eliminating subsequent pro-inflammatory insults, it may be possible to stop this vicious cycle and its associated long-term morbidity.

Finally, there are current clinical implications to our findings. Knowing the high prevalence of poor long-term outcomes amongst septic patients of advanced age, high comorbidity burden and persistent organ failure at 14 days may assist clinicians in providing patients and families with realistic prognoses beyond survival. This could assist with informed decision making both early, with the decision to undergo aggressive resuscitation (sometimes requiring surgical source control), and later in patients with prolonged and complicated ICU stays. Given their outcomes, CCI patients and their families may benefit from early palliative care consultation to assist in this decision making. This is especially true in surgical populations, where triggers for such consultation have been difficult to develop. (31)

CONCLUSIONS

In this unique prospective, long-term outcome study of SICU patient treated for sepsis, we have shown that traditional inpatient outcomes that are commonly utilized measures of quality are not concordant with outcomes at 1-year. The incidence of inpatient or 30-day mortality among patients that survive the initial septic insult is surprisingly low, and the majority exhibit a clinical trajectory of inpatient recovery. However, one-third of sepsis patients develop persistent organ dysfunction and develop a clinical trajectory of chronic critical illness (CCI) and these patients are at high risk of poor functional status and death at 1-year. Recurrent sepsis and persistent organ dysfunction are the leading etiologies of long-term mortality. Older adults and those with significant comorbidity burdens appear to be particularly at risk. Combined clinical and biomarker risk factor stratification will likely be necessary in future interventional trials to select for patients likely to response to interventions targeted to modulate the innate immune response to prevent sepsis recidivism, reduce or reverse organ dysfunction, and improve long-term outcomes among initial survivors of sepsis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions and efforts of Jennifer Lanz, Ruth Davis, Ashley McCray, Jillianne Brakenridge, Eduardo Navarro, Zhongkai Wang and Quran Wu.

Supported in part by grants: P50 GM111152 (SCB, PAE, MSS, AB, SDA, LLM, FAM) awarded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), R03 AG056444 (SCB) from the National Institute on Aging, and by a postgraduate training grant T32 GM008721 (JAS, RBH, MCC) in burns, trauma, and perioperative injury by the NIGMS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Incidence and Trends of Sepsis in US Hospitals Using Clinical vs Claims Data, 2009-2014. JAMA. 2017;318(13):1241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, Soule J, Whippy A, Angus DC, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinley BA, Moore LJ, Sucher JF, Todd SR, Turner KL, Valdivia A, et al. Computer protocol facilitates evidence-based care of sepsis in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2011;70(5):1153–66; discussion 66–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft CA, Moore FA, Efron PA, Marker PS, Gabrielli A, Westhoff LS, et al. Computer versus paper system for recognition and management of sepsis in surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):311–7; discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore LJ, McKinley BA, Turner KL, Todd SR, Sucher JF, Valdivia A, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in general surgery patients. J Trauma. 2011;70(3):672–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner AK, Ghita GL, Wang Z, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Raymond SL, Mankowski RT, et al. The Development of Chronic Critical Illness Determines Physical Function, Quality of Life, and Long-Term Survival Among Early Survivors of Sepsis in Surgical ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stortz JA, Mira JC, Raymond SL, Loftus TJ, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Wang Z, et al. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(2):342–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mira JC, Gentile LF, Mathias BJ, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, et al. Sepsis Pathophysiology, Chronic Critical Illness, and Persistent Inflammation-Immunosuppression and Catabolism Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stortz JA, Murphy TJ, Raymond SL, Mira JC, Ungaro R, Dirain ML, et al. Evidence for Persistent Immune Suppression in Patients Who Develop Chronic Critical Illness After Sepsis. Shock. 2018;49(3):249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loftus TJ, Mira JC, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ghita GL, Wang Z, Stortz JA, et al. Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center investigators: protocols and standard operating procedures for a prospective cohort study of sepsis in critically ill surgical patients. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(4):530–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Ciesla DJ, Biffl WL, Banerjee A. Validation of postinjury multiple organ failure scores. Shock. 2009;31(5):438–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarze ML, Brasel KJ, Mosenthal AC. Beyond 30-day mortality: aligning surgical quality with outcomes that patients value. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(7):631–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milano PK, Desai SA, Eiting EA, Hofmann EF, Lam CN, Menchine M. Sepsis Bundle Adherence Is Associated with Improved Survival in Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(5):774–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Zanten AR, Brinkman S, Arbous MS, Abu-Hanna A, Levy MM, de Keizer NF, et al. Guideline bundles adherence and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):1890–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore FA, Moore EE, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y, Banerjee A, Moldawer LL. The role of NIGMS P50 sponsored team science in our understanding of multiple organ failure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(3):520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Chin TL, Banerjee A, Sperry JL, et al. Temporal trends of postinjury multiple-organ failure: still resource intensive, morbid, and lethal. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(3):582–92, discussion 92–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanzant EL, Lopez CM, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ungaro R, Davis R, Cuenca AG, et al. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome after severe blunt trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(1):21–9; discussion 9–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yende S, Austin S, Rhodes A, Finfer S, Opal S, Thompson T, et al. Long-Term Quality of Life Among Survivors of Severe Sepsis: Analyses of Two International Trials. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guirgis FW, Brakenridge S, Sutchu S, Khadpe JD, Robinson T, Westenbarger R, et al. The long-term burden of severe sepsis and septic shock: Sepsis recidivism and organ dysfunction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(3):525–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, Dhainaut JF, Douglas IS, Finfer S, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2055–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beer S, Weighardt H, Emmanuilidis K, Harzenetter MD, Matevossian E, Heidecke CD, et al. Systemic neuropeptide levels as predictive indicators for lethal outcome in patients with postoperative sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1794–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman G, Silva E, Vincent JL. Has the mortality of septic shock changed with time. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(12):2078–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall JC. Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol Med. 2014;20(4):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J, Cuschieri J, Cuenca AG, Gao H, et al. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuenca AG, Gentile LF, Lopez MC, Ungaro R, Liu H, Xiao W, et al. Development of a genomic metric that can be rapidly used to predict clinical outcome in severely injured trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1175–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sweeney TE, Perumal TM, Henao R, Nichols M, Howrylak JA, Choi AM, et al. A community approach to mortality prediction in sepsis via gene expression analysis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francois B, Jeannet R, Daix T, Walton AH, Shotwell MS, Unsinger J, et al. Interleukin-7 restores lymphocytes in septic shock: the IRIS-7 randomized clinical trial. JCI Insight. 2018;3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotchkiss RS, Colston E, Yende S, Angus DC, Moldawer LL, Crouser ED, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Sepsis: A Phase 1b Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Single Ascending Dose Study of Antiprogrammed Cell Death-Ligand 1 (BMS-936559). Crit Care Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilley EJ, Cooper Z, Schwarze ML, Mosenthal AC. Palliative Care in Surgery: Defining the Research Priorities. Ann Surg. 2018;267(1):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.