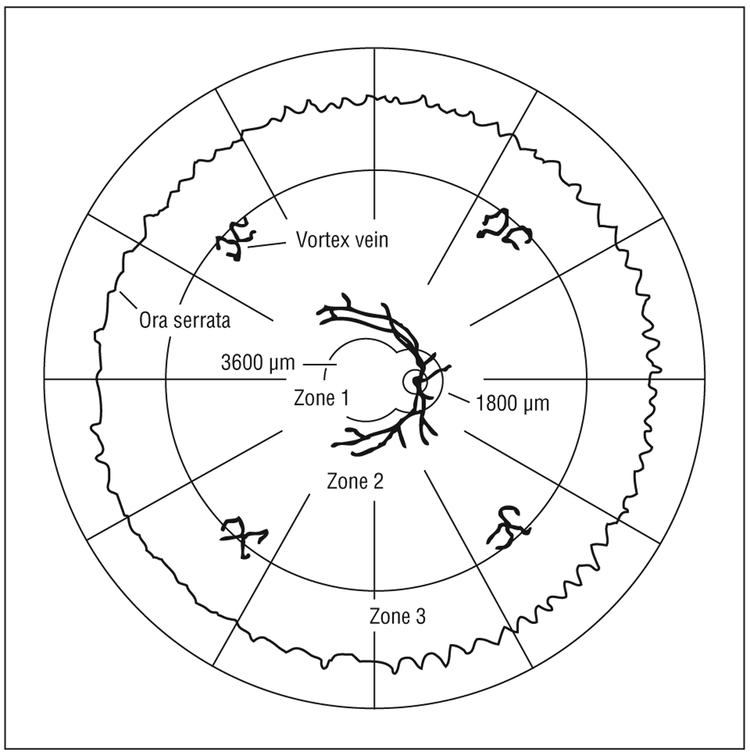

Holland and colleagues1 introduced the technique of localizing infectious retinitis lesions to 1 or more of 3 contiguous retinal zones in 1989, an approach first applied to the study of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. As defined in the original study, zone 1 corresponded to an area comprising both 2 disc diameters (3600 μm) from the foveal center and 1 disc diameter (1800 μm) from the margins of the optic disc, an area wherein most immediately sight-threatening lesions reside2; zone 2 was defined as the area extending from zone 1 to the clinical equator of the eye, identified by the anterior borders of the ampullae of the vortex veins; and zone 3 extended from zone 2 to the ora serrata, an area underlying the vitreous base and associated with an increased risk of retinal detachment (Figure 1). Studies of retinitis location, size, and progression are often done photographically in collaboration with a certified reading center using standardized protocols, photographs, and measuring techniques.3 In general, there is good agreement both between individual reading center graders and between separate reading centers,4 whereas clinicians tend to consistently overestimate retinitis lesion size by about a factor of 2.5 The zonal system, as originally developed for cytomegalovirus retinitis, was adopted for the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS4 and has since been applied to other forms of retinitis, most notably ocular toxoplasmosis,6 but is distinct from the zonal classification (I, II, III) used in the study of retinopathy of prematurity.7

Figure 1.

Retinal zonal topography, modified after Holland and colleagues.1 One disc diameter is approximately 1800 μm.

One aspect of retinal topography that has yet to be addressed is the proportionate area represented by each zone. Such an analysis would, we believe, provide valuable information for both clinicians who care for patients with necrotizing infections of the retina and for investigators who study these conditions. It has been suggested, for example, that new retinitis lesions are not randomly distributed8,9 but rather might preferentially involve selected zones. To determine whether such a hypothesis is true, one must first have a reliable estimate of proportionate topographic area for the various retinal zones. To this end, we compared photographic estimates4 of the area of zones 1 and 2, the only zones readily photographable, with an estimate of zone 3 area derived by subtracting the sum of the areas of zones 1 and 2 from a known total human retinal area of approximately 1000 mm2.10 Given that such estimates would be expected to vary somewhat from person to person, we then rounded the proportionate areas to the nearest fifth percentile. This approach provided an estimate of proportionate area for zone 1 of approximately 5% of the entire retina; for zone 2, of about 70%; and for zone 3, the remaining 25% (Figure 2). We propose that such evidence-based estimates be used both by clinicians to document and monitor necrotizing retinitis lesions and for future studies of retinitis location, size, and progression.

Figure 2.

Proportionate zonal representation as estimated from both photographic4 and human anatomical10 studies.*Zones 1 and 2 from NTS accession No. PB97-192082.4 †Zone 3 from Curcio and Allen.10 ‡Rounded to the nearest fifth percentile.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by the Pacific Vision Foundation (Dr Cunningham), San Francisco, the San Francisco Retina Foundation (Dr Cunningham), the National Eye Institute via the Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS (grants U10 EY 08067 [University of Wisconsin, Madison] and EY08057 [University of California, Los Angeles]), and Research to Prevent Blindness (University of Wisconsin).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Role of Sponsors: The supporters had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Emmett T. Cunningham, Jr, Department of Ophthalmology, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, and Department of Ophthalmology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford.

Larry D. Hubbard, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Ronald P. Danis, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Gary N. Holland, Ocular Inflammatory Disease Center, Jules Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- 1.Holland GN, Buhles WC Jr, Mastre B, Kaplan HJ; UCLA CMV Retinopathy Study Group. A controlled retrospective study of ganciclovir treatment for cytomegalovirus retinopathy: use of a standardized system for the assessment of disease outcome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(12):1759–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei LL, Park SS, Skiest DJ. Prevalence of visual symptoms among patients with newly diagnosed cytomegalovirus retinitis. Retina. 2002;22(3):278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danis RP. The clinical site-reading center partnership in clinical trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):815–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. SOCA Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Grading Protocol. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service, US Department of Commerce; 1997. NTIS accession PB97-192082. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg DV, Holbrook JT, Hubbard LD, Davis MD,Jabs DA, Holland GN; Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Clinician versus reading center assessment of cytomegalovirus retinitis lesion size. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(4):559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasave AF, Díaz-Llopis M, Muccioli C, Belfort R Jr, Arevalo JF. Intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone for zone 1 toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis at twenty-four months. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(9):1831–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(8):1130–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland GN, Vaudaux JD, Jeng SM, et al. ; UCLA CMV Retinitis Study Group. Characteristics of untreated AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis, I: findings before the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (1988 to 1994). Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. part II: disease manifestations and management. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curcio CA, Allen KA. Topography of ganglion cells in human retina. J Comp Neurol. 1990;300(1):5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]