Abstract

There have been few studies investigating the association between atopic dermatitis (AD) and prenatal exposure to heavy metals. We aimed to evaluate whether prenatal exposure to heavy metals is associated with the development or severity of AD in a birth cohort study. A total of 331 subjects were followed from birth for a median duration of 60.0 months. The presence and severity of AD were evaluated at ages 6 and 12 months, and regularly once a year thereafter. The concentrations of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium in umbilical cord blood were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) were isolated and stimulated for analysis of cytokine production using ELISA. Heavy metal levels in cord blood were not associated with the development of AD until 24 months of age. However, a positive correlation was observed between the duration of AD and lead levels in cord blood (p=0.002). AD severity was also positively associated with chromium concentrations in cord blood (p=0.037), while cord blood levels of lead, mercury, and cadmium were not significantly associated with AD severity (p=0.562, p=0.054, and p=0.055, respectively). Interleukin-13 production in CBMCs was positively related with lead and chromium levels in cord blood (p=0.021 and p=0.015, respectively). Prenatal exposure to lead and chromium is associated with the persistence and severity of AD, and the immune reaction toward a Th2 polarization.

Keywords: Dermatitis, atopic; Cohort studies; Chromium; Fetal blood; Interleukin-13

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory pruritic skin disease mostly occurring in infants and young children. Recent nationwide studies have reported the prevalence of AD to be about 10%–15% in Korean children (1,2). The natural course of AD varies depending on ethnicity, geographical regions, severity, and allergic sensitization (3). Approximately a third of patients with AD occurring in the first year of life showed intermittent or persistent skin symptoms during a mean follow-up period of 60 months, although many cases disappeared over time (3). The chronicity and frequent relapses of AD have a considerably negative impact on the quality of life of affected children and their families (4).

Environmental factors play a critical role in the development of AD by triggering skin barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation or both (5). For example, exposure to fine particulate matter or redecoration activities during the perinatal period may increase the risk of AD development (6,7). Careful attention also has to be paid to heavy metal exposure, such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), chromium (Cr), and cadmium (Cd), because they act as toxicants and people are widely exposed to them through food, water, and air (8,9). High cadmium levels in cord blood were associated with the presence of AD in 6-month-old infants (10). Prenatal lead exposure was linked to an increased risk of sensitization to common inhalant allergens in early childhood (6). Heavy metals were reported to skew immune responses toward a Th2 bias and to increase production of IgE (11). However, studies investigating the association between AD and prenatal exposure to heavy metals are still lacking.

In this prospective birth cohort study, we evaluated whether prenatal exposure to heavy metals is associated with the development or severity of AD in infants by measuring cord blood levels of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium. In addition, we investigated the relationship between cytokine levels and heavy metal concentrations in cord blood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and clinical evaluation

We conducted a population-based, prospective birth cohort study (COhort for Childhood Origin of Asthma and allergic disease; COCOA) (11). Women in the third trimester of pregnancy were enrolled from 4 tertiary hospitals (Asan Medical Center, Samsung Medical Center, Severance Hospital, and CHA Gangnam Medical Center) and 7 public health centers in Seoul from November 2007 to September 2011. The women were asked to respond to a questionnaire regarding basic demographic information, parental history of allergic diseases, and dietary pattern during pregnancy. Neonates were excluded if they were premature or they had a major congenital anomalies or birth asphyxia. Finally, we selected and analyzed 331 subjects who were followed up for at least 2 years, because AD shows chronic course with high relapse rate. The presence of parental history of allergic diseases was defined as having been diagnosed with AD, asthma, or allergic rhinitis by a physician. Information regarding pregnancy and delivery was collected from the medical records shortly after delivery.

During the follow-up period, all the subjects were evaluated at 6 and 12 months of age, and regularly once a year thereafter. The diagnosis of AD was based on the criteria defined by Hanifin and Rajka (12). At consecutive visits, AD patients were assessed by pediatric allergists using the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), ranging from 0 to 103 (13).

Written informed consent was obtained from all pregnant women and the study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2008-0616), Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2009-02-021), Yonsei University (IRB No. 4-2008-0588), and CHA Medical Center (IRB No. 2010-010).

Biochemical analysis of cord blood

Heparinized blood samples were obtained from newborn umbilical cords at birth. Eosinophils were counted and total IgE levels were determined using the Immuno-CAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) system. For the measurement of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium, we used inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent Technologies 7700 series; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The calibration standards were loaded into the auto-sampler and the calibration curve showed satisfactory linearity, with the r of the curve calculated as 0.999. Concentrated red blood cell samples were prepared using a matrix solution (1% ammonium hydroxide, 2% butanol, 0.05% EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, and distilled water). Reading data were analyzed using the Mass Hunter Workstation Ver. B01.01 (Agilent Technologies). The limit of detection of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium was 0.067 µg/l, 0.017 µg/l, 0.068 µg/l, and 0.015 µg/l, respectively.

Cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) were separated on a Histopaque (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) gradient within 24 h of sample collection, and the collected cells were washed with phosphatebuffered saline according to the method described in previous studies (11,14). CBMCs were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 1% antibiotic-mycotic and 10% FBS (all from GIBCO BRL, Eggenstein, Germany). CBMCs were resuspended to 1×105 cells/200 µl/well in 96-well plates and incubated with 100 µg/ml ovalbumin (OVA, chicken egg albumin grade V; Sigma Chemical Co.) or 10 µl/ml phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-M (GIBCO BRL) for 48 hr, with 1 µCi of [3H]-thymidine added to each well for the final 12 hr. The cells were harvested onto microfiber filters (Simport, Beloeil, Canada) and the radioactivity on the dried filters was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. The supernatants of PHA-stimulated cells were obtained after 48 hr in culture and stored at −70°C until assayed for IL-13 and IFN-γ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using commercially available kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). All supernatants were assayed in duplicate. The limits of detection were 62.5 pg/ml for IL-13 and 15.6 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Statistical analyses

Data were presented as medians and ranges or numbers and percentages, and analyzed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA). The levels of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium were log-transformed due to their highly skewed distributions: logeCr, loge(loge(Cd×10)+10), logePb, and logeHg. We used the generalized estimating equation method for binary data with logit link function to investigate the association between each of heavy metal levels and the development of AD lesions until 24 months of age. Bivariate associations between heavy metal levels and disease duration were assessed in patients with AD lasting for more than 6 months, using partial Spearman's correlation analysis after adjusting the variables with p value less than 0.2 in a univariable analysis. In addition, the relationship of SCORAD index with each heavy metal concentrations was analyzed in subjects with AD using a mixed model for repeated measurements. The mixed model was also applied to analyze the association of heavy metal levels with eosinophil, total IgE, IL-13, and IFN-γ levels in cord blood. Total IgE levels were transformed with a natural logarithm for association analysis. Variables with a p value of less than 0.2 on univariable analysis were chosen for multivariable analysis. Candidate variables for adjustment included gender, delivery mode, gestational age, parental history of allergic diseases, presence of siblings, maternal education level, season of birth, pet ownership during pregnancy, home remodeling during pregnancy, exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life, and antibiotic treatment during the first 6 months of life. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of subjects

In the present study, a total of 331 children (142 boys and 189 girls) followed up for at least 2 years were analyzed (Table 1). There were no patients lost to follow up in 331 children who were included in the final analysis. The median follow-up duration was 60 months (range, 24.0–69.0 months). The median levels of lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium in cord blood were 1.3 µg/dl (range, 0.2–4.3 µg/dl), 7.2 µg/l (range, 1.6–71.5 µg/l), 6.9 µg/l (range, 1.5–20.5 µg/l), and 0.1 µg/l (range, 0–2.5 µg/l), respectively. The median levels of total IgE and eosinophils in cord blood were 0.3 IU/ml (range, 0–100.0 IU/ml) and 3.0% (range, 0%–14.0%), respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of subjects (n=331).

| Characteristic | No. of subjects (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=331) | AD (n=137) | Non-AD (n=194) | ||

| Male | 142 (42.9) | 51 (37.2) | 91 (46.9) | |

| Delivery method | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | 225 (68.0) | 92 (67.2) | 133 (68.6) | |

| Cesarean section | 106 (32.0) | 45 (32.8) | 61 (31.4) | |

| Season of birth | ||||

| Spring | 82 (24.8) | 35 (25.6) | 47 (24.2) | |

| Summer | 73 (22.1) | 25 (18.2) | 48 (24.7) | |

| Autumn | 99 (29.9) | 45 (32.8) | 54 (27.8) | |

| Winter | 77 (23.3) | 32 (23.4) | 45 (23.2) | |

| Maternal history of allergic diseases | 95 (28.7) | 41 (29.9) | 54 (27.8) | |

| Presence of older siblings | 162 (48.9) | 70 (51.1) | 92 (47.4) | |

| Pet ownership during pregnancy | 20 (6.0) | 9 (6.6) | 11 (5.7) | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months | 106 (32.0) | 43 (31.4) | 63 (32.5) | |

| Antibiotic treatment during the first 6 months | 129 (39.0) | 60 (43.8) | 69 (35.6) | |

| Cord blood measurements* | ||||

| Total IgE (IU/ml) | 0.3 (0–100.0) | 0.2 (0–10.2) | 0.3 (0–100.0) | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 3.0 (0–14.0) | 2.9 (0–14.0) | 3.0 (0–13.0) | |

| IL-13 (pg/ml) | 1,271.4 (20.1–6,574.6) | 1,044.5 (26.3–5,955.7) | 1,513.0 (20.1–6,574.6) | |

| IFN-γ (pg/ml) | 294.3 (0–2,923.7) | 233.4 (0–2,923.7) | 324.4 (0–2,450.8) | |

*Values are presented as median (range).

Associations between heavy metal levels and the development of AD

Among 331 children, 137 (41.4%) patients developed AD during the follow-up period. There were no differences in lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium levels between subjects with and without AD (p=0.262, p=0.541, p=0.389, and p=1.000, respectively). Univariable and multivariable analyses did not show significant relationships between lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium levels in cord blood and the risk of developing AD (all p>0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable analyses for factors influencing the development of AD.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Lead* | 0.995 | 0.626–1.580 | 0.956 | 0.598–1.529 |

| Mercury* | 0.972 | 0.730–1.294 | 0.981 | 0.726–1.324 |

| Chromium* | 1.455 | 0.889–2.380 | 1.449 | 0.883–2.376 |

| Cadmium† | 3.503 | 0.250–49.083 | 2.525 | 0.197–32.419 |

Multivariable analysis was performed after adjustment for gender and parental history of allergic diseases.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

*The values were log-transformed; †The levels were transformed to loge(loge(Cd×10)+10).

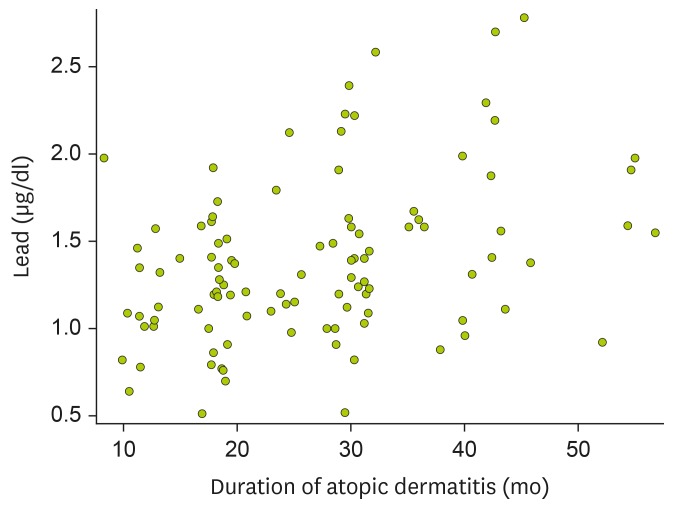

Associations between heavy metal levels and duration of AD

When we evaluated the associations between heavy metal levels in cord blood and the disease duration in 103 patients with AD lasting for more than 6 months, a significant correlation was found between lead levels and the duration of AD in both univariable (ρ=0.346, p<0.001) and multivariable (ρ=0.308, p=0.002) analyses (Fig. 1). However, there were no significant correlations between cord blood levels of mercury, chromium, and cadmium and the duration of AD.

Figure 1. Correlation between lead levels in cord blood and the duration of AD in 103 children whose skin symptoms lasted for more than 6 months. Statistical analysis was done using partial Spearman's correlation analysis after adjustment for gender, presence of siblings, season of birth, and antibiotic treatment during the first 6 months of life (ρ=0.308, p=0.002).

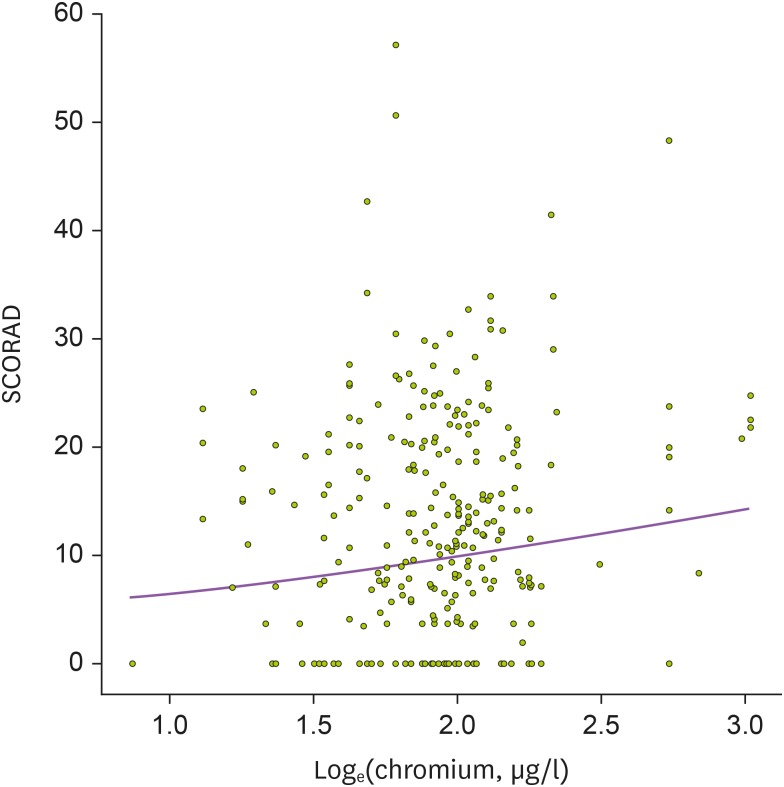

Associations between heavy metal levels and the severity of AD

When we evaluated the associations between heavy metal levels in cord blood and AD severity in 137 patients who had AD during the follow-up period, no statistical significance was found between lead, mercury, chromium, and cadmium levels in cord blood and SCORAD index (p=0.981, p=0.113, p=0.055, and p=0.076, respectively) in univariable analysis (Table 3). However, multivariable analysis showed a positive association between SCORAD index and chromium concentrations in cord blood (p=0.037; Fig. 2). Cord blood levels of lead, mercury, and cadmium were not significantly associated with AD severity in the multivariable analysis (p=0.562, p=0.054, and p=0.055, respectively).

Table 3. Relationship between heavy metal levels in umbilical cord blood and SCORAD* index in children with AD.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | p value | Beta coefficient | p value | |

| Lead* | 0.003 | 0.123 | 1.113 | 0.562 |

| Mercury* | 0.115 | 0.072 | 2.179 | 0.054 |

| Chromium* | 0.260 | 0.135 | 0.277 | 0.037 |

| Cadmium† | 1.524 | 0.855 | 25.258 | 0.055 |

Multivariable analysis was performed after adjustment for maternal history of allergic diseases, maternal education level, exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life, and season of birth.

*The values were log-transformed; †The levels were transformed to loge(loge(Cd×10)+10).

Figure 2. Association between mercury levels in cord blood and SCORAD in children with AD. Mixed model was applied after adjustment for season of birth (p=0.004).

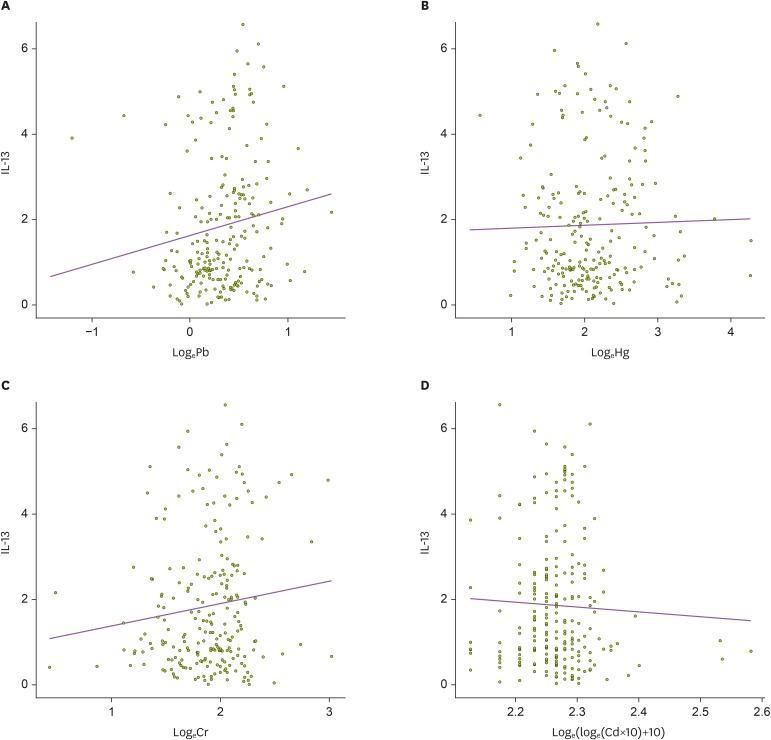

Associations between heavy metal levels and biochemical profiles in cord blood

Univariable analysis in 331 children showed that IL-13 levels in cord blood were positively related with lead levels in cord blood (p=0.028), although there were no significant associations between mercury, chromium, and cadmium levels and IL-13 levels (p=0.726, p=0.075, and p=0.520, respectively; Table 4). The multivariable analysis revealed that cord blood levels of lead and chromium levels were positively related to IL-13 levels in cord blood (p=0.021 and p=0.015, respectively; Fig. 3). However, total IgE levels, percentage of eosinophils, and IFN-γ levels in cord blood showed no significant relationship with the concentrations of any heavy metals in univariable and multivariable analyses.

Table 4. Relationship between IL-13 and heavy metal levels in umbilical cord blood.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | p value | Beta coefficient | p value | |

| Lead* | 0.676 | 0.028 | 0.692 | 0.021 |

| Mercury* | 0.067 | 0.726 | 0.102 | 0.585 |

| Chromium* | 0.530 | 0.075 | 0.713 | 0.015 |

| Cadmium† | −1.139 | 0.520 | −0.388 | 0.824 |

Multivariable analysis was performed after adjustment for gender, presence of siblings, and season of birth.

*The values were log-transformed; †The levels were transformed to loge(loge(Cd×10)+10).

Figure 3. Relationship between heavy metal levels and IL-13 in umbilical cord blood. Mixed model was applied to analyze the association of IL-13 with (A) lead (Pb, µg/dl), (B) mercury (Hg, µg/l), (C) chromium (Cr, µg/l), and (D) cadmium (Cd, µg/l). IL-13 levels in cord blood was positively correlated with only lead levels in cord blood (p=0.028).

DISCUSSION

Only a few studies have reported the relationship between prenatal exposure to heavy metals and the occurrence of allergic diseases (10). In the present study, we found that AD persisted for longer periods in children with higher lead levels in cord blood and children with higher cord blood levels of chromium in cord blood were associated with more severe AD symptoms. In addition, chromium and lead were associated with IL-13 levels in cord blood. It means that exposure to chromium during prenatal period does not develop AD, but may be involved in aggravation of skin symptoms through Th2 skewing. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that fetal exposure to heavy metals may contribute to the persistence and severity of AD in early childhood.

Lead and chromium are common environmental pollutants which the general population are frequently exposed to (15,16). Lead is found in paint, food, and other products such as gasoline (16). Chromium, released from industries that use the element, is also detected in the air, soil, and water (17). The heavy metal levels of cord blood in the present study were similar to those reported in previous studies conducted in Korea, China, Poland, and Spain, while cadmium levels seem to be lower than those in other studies (6,10,16,18,19). None of the subjects showed lead concentrations above the reference value of 5 µg/dl established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (20), indicating that even low levels of intrauterine exposure to lead may harm children's health. This is consistent with experimental animal studies in which lead exposure in fetuses induced more immune alterations than in adults, even at very low levels of exposure (21,22). Moreover, certain species of animals showed lead-induced immunotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner (23). It remains unclear whether the adverse effect of chromium on AD severity in Korean infants is attributed to the exposed amount or other reasons such as the valence of chromium ion.

Our results are different from those of a previous Korean study in which high cadmium levels in cord blood were associated with the presence of AD at 6-months of age (10). It might be due to different methods of diagnosing AD. While we directly examined the infants and children for the diagnosis of AD, they evaluated AD in 6-month-old infants using a questionnaire in the previous study (10). Because young infants often exhibit a variety of skin rashes mimicking AD, the diagnostic accuracy could be low when the diagnosis is relied upon questionnaires alone (24,25).

There was no association between the concentration of heavy metals in cord blood and biomarkers for immune dysregulation such as IgE, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, and IL-33 (26). By contrast, other studies demonstrated that exposure to chromium or lead alters humoral and cellular immunity, and is associated with atopy or allergic diseases (27,28,29). Pakistani children working in the surgical instrument-manufacturing industry showed a 35 times higher urinary concentration of chromium and a higher prevalence of asthma than schoolchildren in the same country (30). Co-exposure to OVA and the inhaled particulate hexavalent chromium in BALB/c mice induced more severe airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness than those exposed to OVA alone (17). In children with a mean age of 9.9 years in Hong Kong, blood lead levels were positively related with AD severity and poor quality of life (27). In that study, cord blood lead concentration also showed a positive relationship with peripheral blood eosinophil counts and serum total IgE levels, suggesting that children's atopic status might be affected by prenatal exposure to lead (27). A recent study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for adults in the US revealed that blood lead concentrations were related to total IgE levels and allergic sensitization to dust mites and arthropods (28). However, those studies were designed as cross-sectional observational studies, and thus had limitations for identifying causal relationships. The impact of heavy metal exposure during the perinatal period on AD was not evaluated in those studies (27,28).

Prenatal exposure to heavy metals has been reported to skew toward Th2 immune responses and to increase production of IgE, although the exact mechanism is not fully understood (6,29,31,32). In a birth cohort study, it was shown that prenatal exposure to lead may enhance sensitization to common inhalant allergens at the age of 5 years (6). In addition, lead exposure led to the production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 and suppressed IFN-γ expression in an animal model (29). Mercuric chloride promoted the release of histamine, IL-4, IL-13, and leukotriene C4 from human basophils (31). In mice challenged with potassium dichromate, serum total IgE levels were higher than those in the control group (32). In accordance with previous studies, our study showed a positive association between IL-13 expression and lead and chromium levels in cord blood. In addition, a trend for relationship between mercury and cadmium levels in cord blood and AD severity was seen, with p value of 0.054 and 0.055. Taken together, our findings raise the possibility that intrauterine exposure to heavy metals may influence the clinical severity of AD by modifying the immune reaction toward a Th2 polarization.

A limitation of the present study was that we did not measure the blood concentration of heavy metals in our subjects after birth. Therefore, it was difficult to determine how long the hazardous impact of heavy metal exposure during the fetal period was maintained. Secondly, we failed to find the source of heavy metal exposure in the present study, although previous Korean studies have showed that blood lead levels in the general population were associated with tobacco smoking, drinking, and certain dietary intake such as seafood and vegetables (33,34). Identification of sources and exposure routes is needed to effectively minimize the prenatal exposure to heavy metals.

In conclusion, prenatal exposure to lead and chromium is associated with the duration and severity of AD, and the immune reaction toward a Th2 polarization. Future studies could highlight the importance of the avoidance of heavy metal exposure during pregnancy to alleviate severe skin symptoms in infants with AD.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (fund code 2008-E33030-00, 2009-E33033-00, 2011-E33021-00, 2012-E33012-00, 2013-E51003-00, 2014-E51004-01) and the Environmental Health Center grants funded by the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea. We appreciate Youngshin Han and Jaehee Choi for their data collection.

Abbreviations

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- CBMC

cord blood mononuclear cell

- Cd

cadmium

- COCOA

COhort for Childhood Origin of Asthma and allergic disease

- Cr

chromium

- Hg

mercury

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- OVA

ovalbumin

- Pb

lead

- PHA

phytohemagglutinin

- SCORAD

SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Kim J, Kim S.

- Data curation: Kim J, Chung JY, Hong YS, Oh SY, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Kim KW, Shin YH, Won HS, Lee KJ, Kim SH, Kwon JY, Lee SH, Hong SJ, Ahn K.

- Formal analysis: Kim S, Woo SY.

- Funding acquisition: Hong SJ, Ahn K.

- Methodology: Kim J, Kim S, Woo SY, Hong SJ, Ahn K.

- Project administration: Hong SJ, Ahn K.

- Software: Kim S, Woo SY.

- Supervision: Hong SJ, Ahn K.

- Writing - original draft: Kim J, Kim S.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim S, Chung JY, Hong SJ, Ahn K.

References

- 1.Kim CH, Kim SH, Lee JS. Association of maternal depression and allergic diseases in Korean children. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38:300–308. doi: 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang HK, Choi J, Kim WK, Lee SY, Park YM, Han MY, Kim HY, Hahm MI, Chae Y, Lee KJ, et al. The association between hypovitaminosis D and pediatric allergic diseases: a Korean nationwide population-based study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37:64–69. doi: 10.2500/aap.2016.37.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung Y, Kwon JH, Kim J, Han Y, Lee SI, Ahn K. Retrospective analysis of the natural history of atopic dermatitis occurring in the first year of life in Korean children. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:723–728. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.7.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:52. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0281-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn K. The role of air pollutants in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jedrychowski W, Perera F, Maugeri U, Miller RL, Rembiasz M, Flak E, Mroz E, Majewska R, Zembala M. Intrauterine exposure to lead may enhance sensitization to common inhalant allergens in early childhood: a prospective prebirth cohort study. Environ Res. 2011;111:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbarth O, Fritz GJ, Rehwagen M, Richter M, Röder S, Schlink U. Association between indoor renovation activities and eczema in early childhood. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2006;209:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Järup L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br Med Bull. 2003;68:167–182. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim NH, Hyun YY, Lee KB, Chang Y, Ryu S, Oh KH, Ahn C. Environmental heavy metal exposure and chronic kidney disease in the general population. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:272–277. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.3.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Jeong KS, Ha EH, Park H, Ha M, Hong YC, Lee SJ, Lee KY, Jeong J, Kim Y. Association between prenatal exposure to cadmium and atopic dermatitis in infancy. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:516–521. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang HJ, Lee SY, Suh DI, Shin YH, Kim BJ, Seo JH, Chang HY, Kim KW, Ahn K, Shin YJ, et al. The Cohort for Childhood Origin of Asthma and allergic diseases (COCOA) study: design, rationale and methods. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;92:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HB, Ahn KM, Kim KW, Shin YH, Yu J, Seo JH, Kim HY, Kwon JW, Kim BJ, Kwon JY, et al. Cord blood cellular proliferative response as a predictive factor for atopic dermatitis at 12 months. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1320–1326. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.11.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra KP. Lead exposure and its impact on immune system: a review. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:969–972. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Esquinas E, Pérez-Gómez B, Fernández-Navarro P, Fernández MA, de Paz C, Pérez-Meixeira AM, Gil E, Iriso A, Sanz JC, Astray J, et al. Lead, mercury and cadmium in umbilical cord blood and its association with parental epidemiological variables and birth factors. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:841. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider BC, Constant SL, Patierno SR, Jurjus RA, Ceryak SM. Exposure to particulate hexavalent chromium exacerbates allergic asthma pathology. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;259:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng G, Zhong H, Guo Z, Wu Z, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhou Y, Zuo Z. Levels of heavy metals and trace elements in umbilical cord blood and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;160:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Chen Q, Wei X, Chen L, Zhang X, Chen K, Chen J, Li T. Relationship between perinatal antioxidant vitamin and heavy metal levels and the growth and cognitive development of children at 5 years of age. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24:650–658. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.4.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J R Stat Soc B. 2000;62:711–730. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller TE, Golemboski KA, Ha RS, Bunn T, Sanders FS, Dietert RR. Developmental exposure to lead causes persistent immunotoxicity in Fischer 344 rats. Toxicol Sci. 1998;42:129–135. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietert RR, Piepenbrink MS. Perinatal immunotoxicity: why adult exposure assessment fails to predict risk. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:477–483. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunn TL, Dietert RR, Ladics GS, Holsapple MP. Developmental immunotoxicology assessment in the rat: age, gender, and strain comparisons after exposure to lead. Toxicol Methods. 2001;11:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chadha A, Jahnke M. Common neonatal rashes. Pediatr Ann. 2019;48:e16–e22. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20181206-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SC Committee of Korean Atopic Dermatitis Association for REACH. Various diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD): a proposal of Reliable Estimation of Atopic Dermatitis in Childhood (REACH) criteria, a novel questionnaire-based diagnostic tool for AD. J Dermatol. 2016;43:376–384. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashley-Martin J, Levy AR, Arbuckle TE, Platt RW, Marshall JS, Dodds L. Maternal exposure to metals and persistent pollutants and cord blood immune system biomarkers. Environ Health. 2015;14:52. doi: 10.1186/s12940-015-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hon KL, Wang SS, Hung EC, Lam HS, Lui HH, Chow CM, Ching GK, Fok TF, Ng PC, Leung TF. Serum levels of heavy metals in childhood eczema and skin diseases: friends or foes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:831–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Min KB, Min JY. Environmental lead exposure and increased risk for total and allergen-specific IgE in US adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao D, Kasten-Jolly J, Lawrence DA. The paradoxical effects of lead in interferon-gamma knockout BALB/c mice. Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:444–453. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sughis M, Nawrot TS, Haufroid V, Nemery B. Adverse health effects of child labor: high exposure to chromium and oxidative DNA damage in children manufacturing surgical instruments. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1469–1474. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strenzke N, Grabbe J, Plath KE, Rohwer J, Wolff HH, Gibbs BF. Mercuric chloride enhances immunoglobulin E-dependent mediator release from human basophils. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;174:257–263. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ban M, Langonné I, Goutet M, Huguet N, Pépin E. Simultaneous analysis of the local and systemic immune responses in mice to study the occupational asthma mechanisms induced by chromium and platinum. Toxicology. 2010;277:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh E, Shin H, Yon M, Nam JW, Lee Y, Kim D, Lee J, Kim M, Park SK, Choi H, et al. Measures for a closer-to-real estimate of dietary exposure to total mercury and lead in total diet study for Koreans. Nutr Res Pract. 2012;6:436–443. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2012.6.5.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JU, Oh SW, Kim SH, Kim YH, Park RJ, Moon JD. A Study on the association between blood lead levels and habitual tobacco and alcohol use in Koreans with no occupational lead exposure. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2008;20:165–173. [Google Scholar]