Abstract

We measured the steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence spectral properties of cadmium-enriched nanoparticles (CdS–Cd2+). These particles displayed two emission maxima, at 460 and 580 nm. The emission spectra were independent of excitation wavelength. Surprisingly, the intensity decays were strongly dependent on the observation wavelength, with longer decay times being observed at longer wavelengths. The mean lifetime increased from 150 to 370 ns as the emission wavelength was increased from 460 to 650 nm. The wavelength-dependent lifetimes were used to construct the time-resolved emission spectra, which showed a growth of the long-wavelength emission at longer times, and decay-associated spectra, which showed the longer wavelength emission associated with the longer decay time. These nanoparticles displayed anisotropy values as high as 0.35, depending on the excitation and emission wavelengths. Such high anisotropies are unexpected for presumably spherical nanoparticles. The anisotropy decayed with two correlation times near 5 and 370 ns, with the larger value probably due to overall rotational diffusion of the nanoparticles. Addition of a 32-base pair oligomer selectively quenched the 460-nm emission, with less quenching being observed at longer wavelengths. The time-resolved intensity decays were minimally affected by the DNA, suggesting a static quenching mechanism. The wavelength-selected quenching shown by the nanoparticles may make them useful for DNA analysis.

In the mid-1980s several reports appeared which demonstrated that colloidal suspensions of semiconductors were luminescent and that the spectral properties of these colloids depended on the size of the colloids (1–4). It is now known that the spectral properties are due to nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 20 to 100 Å. During the subsequent 15 years there has been extensive research to develop simple methods for the preparation of homogeneously sized and highly luminescent nanoparticles. Recent review articles (5–10) summarize the state of the art. Luminescent nanoparticles can be made from a variety of materials, including CdS, CdSe, ZnO, ZnS, and PbS. Semiconductor nanoparticles (NP)2 display spectral properties which depend more on the size of the particle than on the bulk properties of the material. As the size of the particles decreases, the absorption and emission shift to shorter wavelengths. For instance, cadmium phosphide in the bulk phase is black, due to the small band gap near 0.5 eV. As the particle size decreases, the material changes from black to red and eventually white as the band gap increases to 4 eV (7). Nanoparticles can show multiple emission maxima. High-energy emission that is near the long-wavelength absorption edge of the nanoparticles is termed band-edge luminescence, although it has been found that the emission is more likely due to electron–hole pair radiative recombination from shallow trap states than from the band edges (36). Broad emission at longer wavelength is due to recombination of the charge carriers via surface traps having energy levels in the forbidden band gap. Localization of the photogenerated charge carriers upon excitation to trap states occurs on the subpicosecond time scale (36). This surface localization is a dominate source of nonradiative decay. Surface treatment of the NP can decrease the rate of nonradiative decay and increases the emission quantum yield.

The present knowledge of NP chemistry and photophysics suggests their use in fluorescent probes. Two recent reports demonstrated this possibility (11, 12). These groups demonstrated that highly luminescent, homogeneously sized nanoparticles could be prepared and used in the presence of proteins and cellular components. The quantum yield of the NP was increased by a surface coating the semiconductor NP with a higher band gap material. This procedure eliminates trap states within the band gap and promotes band edge luminescence from radiative recombination of the electron–hole pair (8). The particles were conjugated to proteins and shown to display an agglutination reaction with antibodies and to be transported into fibroblasts.

In these biological applications (11, 12), the nanoparticles were used as tracers which indicated the amount and location of the NP and conjugated macromolecules. However, the sensitivity of NP emission to the surface chemistry also suggests their use as sensors as well as tracers (13). For instance, CdS and Cd3As2 display dramatic increases in emission intensity, up to 4-fold, in the presence of alkylamines (14), and CdS particles are quenched by benzyl alcohol (15). The emission of porous silicon, thought to be partially composed of Si nanoparticles, can be quenched by oxygen-containing solvents and amines (16–18), and porous silicon can display pH-dependent intensities (19). These properties are analogous to fluorescent sensors for which the emission intensity, wavelength, or lifetime is sensitive to the presence of analytes such as H+, Ca2+, Cl−, or oxygen (20, 21). Additionally, the emission spectra and intensities of some CdS nanoparticles are sensitive to surface binding of linear and curved DNA, with larger spectral changes being observed for curved DNA (22, 23).

In the present report, we describe the time-resolved spectral properties of CdS nanoparticles with the surface enriched by Cd2+. The NP are first formed by arrested precipitation of Cd2+ with Na2S in the presence of a stabilizing agent. The colloid is then reacted with NaOH and Cd2+. This procedure resulted in increased emission intensity. We show that the intensity decays of these NP depend on emission wavelength, that the NP display polarized emission, and that the emission spectra are sensitive to the binding of DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Spectroscopic Measurements

Frequency-domain (FD) intensity and anisotropy decays were measured as described previously (24). The excitation source was a HeCd laser at 442 nm. The continuous output of this laser was amplitude modulated with a Pockel’s cell. The FD data were interpreted in terms of multiexponential model,

| [1] |

where αi(λ) are the preexponential factors at each emission wavelength and τi are the decay times. The fractional contribution of each decay time component to the steady-state emission is given by

| [2] |

The parameter values were recovered by nonlinear least squares (25). The wavelength-dependent data were also analyzed with the decay times as wavelength-independent parameters and the amplitudes as wavelength-dependent parameters. This is referred to as a global analysis, in which the decay times are global parameters (26). The mean decay times were calculated using

| [3] |

Decay-associated spectra (DAS) (27) were associated with each decay time calculated using

| [4] |

where I(λ) is the steady-state emission spectrum. To avoid confusion, we note that these DAS were calculated using the fi(λ) values (Eq. [2]), and not the αi(λ) values.

Time-resolved emission spectra were calculated from the wavelength-dependent decay I(t) according to published procedures (28–30). Frequency-domain anisotropy decay data were measured and analyzed as described previously (31) in terms of multiple correlation times,

| [5] |

In this expression, r0k is the fractional anisotropy amplitude of a decay with a correlation time θk.

Preparation of CdS–Cd2+-Rich Nanoparticles

The CdS nanoparticles were prepared as described previously (22, 32, 33). To a three-neck round-bottom flask with a stir bar was added 100 mL of purified and deionized water (Continental Waters Systems). The water was deoxygenated by sparging with nitrogen gas for ~20 min, and the subsequent steps were performed in dim light and under an N2 blanket. Cd(NO3)2 · 4H2O and Na6(PO3)6 were added as solids to produce a 2 × 10−4 M solution in each. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 9.8 with 0.01 M NaOH. Anhydrous Na2S (1.6 mg, to yield 2 × 10−4 M sulfide) was dissolved in 2 mL of water and this solution was added dropwise to the Cd2+–polyphosphate solution with vigorous stirring. The solution turned yellow; stirring was continued for 20 min. Under ultraviolet illumination, the solution glowed orange-pink.

To surface-enrich the CdS nanoparticles with Cd2+, the pH of 5 mL of the stock solution was brought to 10.5 with 0.01 M NaOH. Aliquots of 0.1 M Cd(NO3)2 · 4H2O were added and the reaction was monitored by photoluminescene spectroscopy until the high-energy band at 480 nm was at its maximum intensity (roughly an 8-fold addition of Cd2+). Visually, the solution emitted yellow. The resulting CdS–Cd2+ nanoparticles were characterized by absorption and emission spectroscopy and by transmission electron microscopy; the average nanoparticle diameter was 40 Å ± 15%.

Bent DNA Oligomers

The oligonucleotide 5′-GGCAATTTTTTGGACCGGCAATTTTTTGGACC-3′ and its complement 3′-CCGTTAAAAAACCTGGCCGTTAAAAAACCTGG-5′ were synthesized by standard means at the USC Institute for Biological Research and Technology’s Oligonucleotide Synthesis Facility. The strands were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography using a reverse-phase column (Hamilton PRP-1) and an aqueous triethylammonium acetate/acetonitrile gradient. The purified DNA was dissolved in buffer (5 mM Tris, 5 mM NaCl, pH 7.2) and the two strands were annealed by heating equimolar amounts to 90°C for a few minutes and slow cooling to room temperature. The final concentration of the 32-mer oligonucleotide was 4.48 mM (nucleotide) based on nearest-neighbor extinction coefficients for the single strands.

RESULTS

Spectral Properties of CdS–Cd2+-Rich Nanoparticles

Absorption and emission spectra of the Cd2+-rich nanoparticles are shown in Fig. 1. The absorption edge near 460 nm represents the band gap for this NP preparation. The emission spectrum displays two maxima, at 460 and 580 nm. The sharp emission centered at 460 nm is the band gap emission due to recombination of electron–hole pairs. The broad longer wavelength emission is thought to be due to radiative charge recombination at surface traps. The emission spectra were independent of the excitation wavelength from 350 to 440 nm. For a size-heterogeneous population of nanoparticles, the emission maxima typically shift to longer wavelengths with longer excitation wavelength. The absence of such a shift suggests that this NP preparation has a reasonably homogeneous size distribution.

FIG. 1.

Absorption and emission spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles. The emission spectra are independent of the excitation wavelength from 350 to 440 nm.

At first glance the absence of a spectral shift for various excitation wavelengths is surprising. One might expect that the shorter and longer wavelength emissions would be selectively excited at shorter and longer excitation wavelengths. The absence of such an effect indicates that both emissions result from the same absorption event and is consistent with rapid localization of the trapped exciton (34–36). Further evidence for these common origins of the short- and long-wavelength emissions is obtained from the excitation spectra (Fig. 2). These spectra were identical for observation at 460 or 580 nm.

FIG. 2.

Uncorrected excitation spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles. The excitation was provided by a 450-W xenon lamp, which is the origin of the peak at 400 nm. The long-wavelength side of the excitation spectrum (>400 nm) corresponds well with the absorption spectrum (see Fig. 1). The excitation spectra are the same for detection of 460 and 580 nm.

The CdS–Cd2+ nanoparticles appear to be spherical in transmission electron microscopy, so they are not expected to display polarized emission. Surprisingly, these nanoparticles displayed significant polarization for all useful excitation and emission wavelengths. The anisotropy decreased across the emission spectrum (Fig. 3), and the overall anisotropy was dependent on the excitation wavelength (Fig. 4). As is typical for organic fluorophores, the highest anisotropy was found when the longest excitation wavelength was used. The fact that the anisotropy approaches, but does not exceed, 0.4 suggests that the polarized emission is due to a transition dipole similar to that found in other fluorophores.

FIG. 3.

Emission anisotropy spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles in 80% propylene glycol at −60°C. The solid line is the emission spectrum collected with 400-nm excitation under the same conditions.

FIG. 4.

Excitation anisotropy spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles in 80% propylene glycol at −60°C.

The nonzero anisotropy observed for these nanoparticles suggests the presence of some structural feature which directs the electronic transition along a defined direction. Such nonzero anisotropies were observed previously for a CdS colloidal composite with a dendrimer (37, 38). There are relatively few reports on polarized emission from nanoparticles. The emission from silicon nanoparticles has been reported to be unpolarized (39) or polarized (40–42). Polarized emission has also been reported for CdSe (43, 44). However, in these cases the polarization either is negative or becomes negative in a manner suggesting a rapid process occurring within the nanoparticle. A constant positive anisotropy is more useful if the nanoparticles are to be used as hydrodynamic probes.

We measured the time-resolved intensity decays of the nanoparticles using the frequency-domain method (Fig. 5). The FD data are characteristic of a strongly heterogeneous decay with widely spaced decay time components. Least-squares analysis of these data yields decay times ranging from 13.6 to 604 ns, as recovered from the three decay time fits (Table 1). The intensity decays are strongly dependent on the observation wavelength, as can be seen from the time-domain decay reconstructed from the three decay time analyses (Fig. 6). Longer decay times were found at longer excitation wavelengths, and the mean decay time increased with observation wavelength (Fig. 7).

FIG. 5.

Frequency-domain intensity decays of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles measured for observation at 460 (top) and 580 nm (bottom). The dashed line (lower panel) is the intensity decay at 460 nm.

TABLE 1.

Multiexponential Analysis of CdS–Cd2+ Nanoparticle Intensity Decays in the Absence and Presence of 32-Mer DNA Oligonucleotides

| Observation wavelength (nm) | [DNA] (mM) |

na |

τi (ns) |

αi | fbi |

c (ns) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 460 | 0 | 1 | 58.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | — | 494.7 |

| 2 | 21.5 | 0.823 | 0.353 | ||||

| 182.8 | 0.177 | 0.647 | 20.5 | ||||

| 3 | 13.6 | 0.688 | 0.202 | ||||

| 81.3 | 0.274 | 0.480 | |||||

| 386.6 | 0.038 | 0.318 | 164.6 | 1.9 | |||

| 580 | 1 | 171.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 575.6 | ||

| 2 | 38.7 | 0.709 | 0.206 | ||||

| 363.8 | 0.291 | 0.794 | 14.7 | ||||

| 3 | 24.3 | 0.619 | 0.121 | ||||

| 177.2 | 0.283 | 0.404 | |||||

| 603.8 | 0.098 | 0.475 | 361.1 | 1.5 | |||

| 460 | 0.41 | 3 | 9.0 | 0.637 | 0.164 | ||

| 37.7 | 0.260 | 0.279 | |||||

| 188.6 | 0.103 | 0.557 | 117.2 | 2.0 | |||

| 0.59 | 3 | 6.1 | 0.714 | 0.169 | |||

| 32.8 | 0.171 | 0.219 | |||||

| 137.2 | 0.115 | 0.612 | 92.1 | 4.7 | |||

| 580 | 0.41 | 3 | 15.0 | 0.653 | 0.107 | ||

| 129.8 | 0.266 | 0.378 | |||||

| 578.9 | 0.081 | 0.515 | 348.2 | 2.7 | |||

| 0.59 | 3 | 10.6 | 0.714 | 0.112 | |||

| 118.0 | 0.227 | 0.394 | |||||

| 565.4 | 0.059 | 0.494 | 327.0 | 3.5 |

Number of decay times in the multiexponential analysis.

fi = αiτi/Σ αjτj.

.

FIG. 6.

Time-domain representation of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticle intensity decays observed at 460 and 580 nm.

FIG. 7.

Dependence of the mean lifetime on the observation wavelength. The dashed line is the emission spectrum under the same conditions.

To obtain additional insight into the time-dependent emission of these nanoparticles, we performed a global analysis, with the decay times as global parameters. It was possible to fit the data at all emission wavelengths with three wavelength-independent decay times (Table 2). We used these impulse response functions to reconstruct the time-resolved emission spectra (Fig. 8). These spectra show that the relative contribution of the long decay time component increases at longer times.

TABLE 2.

Global Analysis of the Wavelength-Dependent Intensity Decays for the CdS–Cd2+-Rich Nanoparticles at 20°C

| Wavelength (nm) |

τ1 = 2.9 ns | τ2 = 56.2 ns | τ3 = 371.5 ns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | f1 | α2 | f2 | α3 | f3 | |

| 460 | 0.838 | 0.157 | 0.150 | 0.551 | 0.012 | 0.293 |

| 470 | 0.873 | 0.188 | 0.115 | 0.488 | 0.012 | 0.324 |

| 490 | 0.869 | 0.181 | 0.118 | 0.486 | 0.012 | 0.333 |

| 505 | 0.867 | 0.167 | 0.118 | 0.446 | 0.015 | 0.387 |

| 510 | 0.906 | 0.225 | 0.082 | 0.401 | 0.012 | 0.374 |

| 520 | 0.878 | 0.160 | 0.102 | 0.366 | 0.020 | 0.474 |

| 530 | 0.845 | 0.123 | 0.128 | 0.369 | 0.027 | 0.508 |

| 540 | 0.831 | 0.113 | 0.140 | 0.375 | 0.029 | 0.512 |

| 560 | 0.835 | 0.103 | 0.128 | 0.309 | 0.037 | 0.588 |

| 580 | 0.828 | 0.098 | 0.132 | 0.311 | 0.040 | 0.591 |

| 600 | 0.791 | 0.077 | 0.160 | 0.307 | 0.049 | 0.616 |

| 620 | 0.785 | 0.072 | 0.163 | 0.297 | 0.052 | 0.631 |

| 650 | 0.765 | 0.062 | 0.172 | 0.273 | 0.063 | 0.665 |

| 660 | 0.773 | 0.061 | 0.159 | 0.245 | 0.068 | 0.694 |

Note. For the global analysis, = 14.8.

FIG. 8.

Time-resolved emission spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles at 20°C. The time-resolved spectra were normalized at 460 nm. The dotted line is the steady-state emission spectrum.

We also examined the decay-associated spectra calculated according to Eq. [4] (Fig. 9). As expected, the long decay time component (τi = 371.5 ns) shows the largest amplitude at long wavelength. It is interesting to notice that all three decay time components make significant contributions at all emission wavelengths. This result can be considered within the framework of an excited-state reaction. Suppose the short-wavelength emission represents the initially excited state and the long-wavelength emission is formed from this state subsequent to light absorption. If the reaction is irreversible, then the long decay time components are not expected to be present at short wavelengths in the initially excited state (45–47). The presence of significant amplitude of the long decay times at 460 nm suggests that the 460-nm emission is formed reversibly from the 560-nm emission and/or these states are in equilibrium prior to emission.

FIG. 9.

Decay-associated emission spectra of the CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles. The amplitudes at each wavelength correspond to the fractional amplitudes in the steady-state emission spectra (fi(λ)).

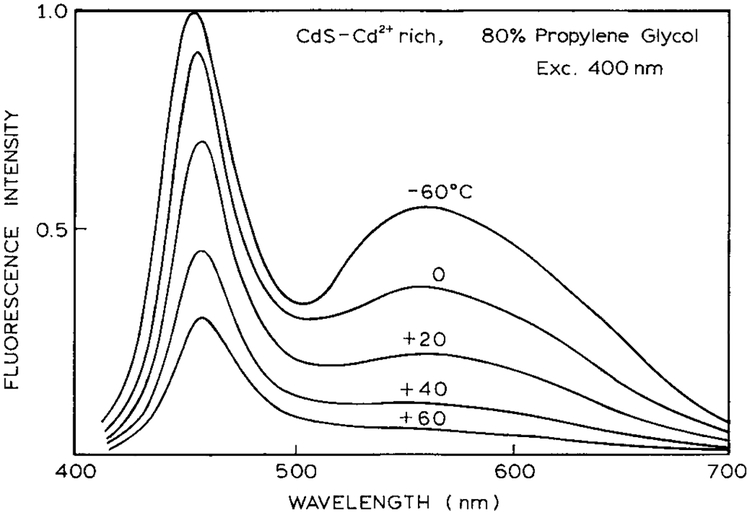

The reversible nature of the 460- and 560-nm emissions is supported to some extent by the temperature-dependent emission spectra (Fig. 10). The intensity of both emissions increases as the temperature is decreased, but at low temperature the relative intensity of the long-wavelength emission increases. However, the changing relative intensities of the two emissions could also be due to changes in the nonradiative decay rates for each emission.

FIG. 10.

Temperature-dependent emission spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles in 80% propylene glycol.

The existence of a nonzero anisotropy suggests the use of anisotropy decay measurements. The FD and time-domain anisotropy decays are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. The FD anisotropy decay could be fit to a two correlation time model with correlation times of 4.8 and 369 ns. The anisotropy decay is strongly multiexponential, with most of the anisotropy decay by the shorter correlation time. The presence of short correlation times is well known for fluorophores bound to proteins or membranes (48). In these cases, the short correlation time is usually due to segmental motions of the fluorophore within the larger macromolecule. In the case of nanoparticles there is no reason to expect such segmental motions. Hence the short anisotropy decay time must be due to some internal process occurring within the nanoparticle.

FIG. 11.

Frequency-domain anisotropy decay of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles at 20°C. The excitation and observation wavelengths were chosen from Fig. 4 to obtain the highest possible r(0) value.

FIG. 12.

Time-domain representation of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticle anisotropy decay.

We questioned the origins of the long correlation time. The correlation time for a molecule of known volume can be calculated from the Stokes–Einstein equation:

| [6] |

In this expression, η is the viscosity, V is the volume, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in degrees kelvin. Based on the diameter of our nanoparticles (45 Å), one can calculate a correlation time of about 13 ns. This correlation time is considerably smaller than the measured value of 369 ns. The CdS is rather dense, 4.8 g/cm3, but the correlation time according to Eq. [6] is independent of the density. At present, we cannot explain the long correlation time we recovered for these nanoparticles.

Effects of DNA on the CdS–Cd2+-Rich Nanoparticles

We examined the effects of a double-stranded 32-mer oligonucleotide on the nanoparticle emission. Based on the sequence, this 32-mer is expected to be bent. Addition of DNA results in quenching of the NP emission (Fig. 13). The extent of quenching depends on emission wavelength, with more quenching at shorter wavelengths (Fig. 14), in accord with other work (22, 23). The lack of Stern–Vlomer quenching was noted previously (23). At first we thought that binding of one 32-mer per nanoparticle resulted in its quenching. We subsequently realized that this cannot occur because such a model does not allow for a change in shape of the emission spectrum. The change in relative intensities of the short- and long-wavelength emissions suggests that the nanoparticles emit with or without bound DNA. This is valuable because the nanoparticles can thus be used as wavelength-ratiometric probes for DNA (Fig. 15).

FIG. 13.

Emission spectra of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles in the absence and presence of the bent DNA 32-mer.

FIG. 14.

Quenching of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles by bent DNA 32-mer (top) as observed at 460 and 580 nm. The Stern–Volmer representation is shown in the bottom panel.

FIG. 15.

Ratio of observed fluorescence intensities at 580 to 460 nm of CdS–Cd2+-rich nanoparticles in the presence of increasing DNA concentrations.

What mechanism could account for the DNA-induced spectral shifts? The activation of the 460-nm emission band by the surface enrichment of Cd2+ suggests that this emission is more sensitive to surface effects than the 580-nm emission; the increased sensitivity of the 460-nm band to DNA absorption is in agreement with this notion. The absorption of long DNA to identically prepared CdS–Cd2+ nanoparticles has been found to be entropically driven, largely by release of counterions from the interface (33); thus, the mechanism for preferential quenching of the 460-nm emission could be the release of the activating Cd2+ ions. Alternatively, the larger relative quenching of the 460-nm emission suggests that the presence of surface-absorbed DNA results in greater surface localization of the charges. Perhaps the negatively charged DNA results in localization of migrating positive charges at this location on the nanoparticle. Irrespective of the mechanism, the spectral changes induced by DNA suggest the possibility of analyte-induced polarization in nanoparticles, which would be a valuable analytical tool.

DISCUSSION

In the preceding section we demonstrated that the emission of a nanoparticle can be sensitive to low concentrations of biomolecules in solution. This sensitivity suggests that nanoparticles can be further developed in chemical sensing (49–54). In the past decade, there have been continued advances in the design and synthesis of fluorescent probes specific for cations near infrared fluorophores and probes which bind with high affinity to DNA. In these cases the spectral changes in response to analytes or bending are intuitively expected because the environment of a small fluorophore is changed. Such analyte-induced changes are not obvious with nanoparticles with sizes comparable to proteins. Since we now know that surface interactions can affect nanoparticle fluorescence, one can now imagine derivatizing their surfaces to provide specific interactions with desired analytes. Such sensing nanoparticles may find widespread applications in biochemical research and medical diagnostics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH, National Institutes for Research Resources, RR-08119.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: DAS, decay-associated spectra; FD, frequency domain; NP, nanoparticles; TD, time domain; TRES, time-resolved emission spectra.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramsden JJ, and Grätzel M (1984) Photoluminescence of small cadmium sulphide particles. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 80, 919–933. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller H, Koch U, Gutièrrez M, and Henglein A (1984) Photochemistry of colloidal metal sulfides. 7. Absorption and fluorescence of extremely small ZnS particles. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem 88, 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuczynski JP, Milosavijevic BH, and Thomas JK (1983) Effect of the synthetic preparation on the photochemical behavior of colloidal CdS. J. Phys. Chem 87, 3368–3370. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossetti R, Nakahara S, and Brus LE (1983) Quantum size effects in the redox potentials, resonance Raman spectra, and electronic spectra of CdS crystallites in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Phys 79(2), 1086–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bawendi MG, Steigerwald ML, and Brus LE (1990) The quantum mechanics of larger semiconductor clusters (“quantum dots”). Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 41, 477–496. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steigerwald ML, and Brus LE (1990) Semiconductor crystallites: A class of large molecules. Acc. Chem. Res 23, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weller H (1993) Colloidal semiconductor Q-particles: Chemistry in the transition region between solid state and molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 32, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alivisatos AP (1996) Perspectives on the physical chemistry of semiconductor nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem 100, 13226–13239. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alivisatos AP (1996) Semiconductor clusters, nanocrystals, and quantum dots. Science 271, 933–937. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy CJ (1996) CdS nanoclusters stabilized by thiolate ligands: A minireview. J. Cluster Sci. 7(3), 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan WCW, and Nie S (1998) Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive nonisotopic detection. Science 281, 2016–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruchez M Jr., Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, and Alivisatos AP (1998) Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Science 281, 2013–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brauns EB, and Murphy CJ (1997) Quantum dots as chemical sensors. Recent Res. Dev. Phys. Chem 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dannhauser T, O’Neil M, Johansson K, Whitten D, and McLendon G (1986) Photophysics of quantized colloidal semiconductors’ dramatic luminescence enhancement by binding of simple amines. J. Phys. Chem 90, 6074–6076. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horvath O (1999) Quenching of CdS fluorescence with benzyl alcohol via transmembrane diffusion in dihexadecyl phosphate vesicles. Langmuir 15, 279–281. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffer JL, Lilley SC, Martin RA, and Files-Sesler LA (1993) Surface reactivity of luminescent porous silicon. J. Appl. Phys 74(3), 2094–2096. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin WJ, Shen GL, and Yu RQ (1998) Organic solvent induced quenching of porous silicon photoluminescence. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 54, 1407–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauerhaas JM, Credo GM, Heinrich JL, and Sailor MJ (1992) Reversible luminescence quenching of porous Si by solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 114, 1911–1912. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chun JKM, Bocarsly AB, Cottrell TR, Benziger JB, and Yee JC (1993) Proton gated emission from porous silicon. J. Am. Chem. Soc 115, 3024–3025. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haugland RP (1996) Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Chemicals (Spence MTZ, Ed.), Molecular Probes, Eugene OR. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakowicz JR (Ed.). (1994) Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 4: Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahtab R, Rogers JP, Singleton CP, and Murphy CJ (1996) Preferential absorption of a “kinked” DNA to a neutral curved surface: Comparisons to and implications for nonspecific DNA–protein interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 118, 7028–7032. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahtab R, Rogers JP, and Murphy CJ (1995) Protein-sized quantum dot luminescence can distinguish between “straight,” “bent,” and “kinked” oligonucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 9099–9100. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakowicz JR, and Gryczynski I (1991) Frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy, in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 1: Techniques (Lakowicz JR, Ed.), pp. 293–335, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straume M, Frasier-Cadoret SG, and Johnson ML (1991) Least-squares analysis of fluorescence data, in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 2: Principles (Lakowicz JR, Ed.), pp. 117–240, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beechem JM, Gratton E, Ameloot M, Knutson JR, and Brand L (1991) The global analysis of fluorescence intensity and anisotropy decay data: Second generation theory and programs, in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 2: Principles (Lakowicz JR, Ed.), pp. 241–305, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knutson JR, Walbridge DG, and Brand L (1982) Decay-associated fluorescence spectra and the heterogeneous emission of alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 21, 4671–4679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Easter JH, DeToma RP, and Brand L (1976) Nanosecond time-resolved emission spectroscopy of a fluorescence probe adsorbed to l-α-egg lecithin vesicles. Biophys. J 16, 571–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor DV, and Phillips D (1984) in Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting, pp. 211–251, Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badea MG, and Brand L (1979) Time-resolved fluorescence measurements. Methods Enzymol. 61, 378–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Kusba J, Gryczynski I, and Johnson ML (1993) Review of fluorescence anisotropy decay analysis by frequency-domain fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Fluoresc 3, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spanhel L, Haase M, Weller H, and Henglein A (1987) Photochemistry of colloidal semiconductors. 20. Surface modification and stability of strong luminescing CdS particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 109, 5649–5655. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahtab R, Harden HH, and Murphy CJ (2000) Temperature and salt-dependent binding of long DNA to protein-sized quantum dots: Thermodynamics of inorganic protein–DNA interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 122, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bawendi MG, Wilson WL, Rothberg L, Carroll PJ, Jedju TM, Steigerwald ML, and Brus LE (1990) Electronic structure and photoexcited-carrier dynamics in nanometer size CdSe clusters. Phys. Rev. Lett 65(13), 1623–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y (1995) Photophysical and photochemical processes of semiconductor nanoclusters. Adv. Photochem 19, 179–231. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagamua T, Inoue H, Grieser F, Urquhart R, Sakaguchi H, and Furlong DN (1999) Ultrafast dynamics of transient bleaching of surface modified cadmium sulphide nano-particles in Nafion films. Colloids Surf., A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 146, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sooklal K, Hanus LH, Ploehn HJ, and Murphy CJ (1998) A blue-emitting CdS/dendrimer nanocomposite. Adv. Mater 10, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Gryczynski Z, and Murphy CJ (1999) Luminescence spectral properties of CdS nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem B103, 7613–7620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brus LE, Szajowski PF, Wilson WL, Harris TD, Schuppler S, and Citrin PH (1995) Electronic spectroscopy and photophysics of Si nanocrystals: Relationship to bulk c-Si and porous Si. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 2915–2922. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrianov AV, Kovalev DI, Zinov’ev NN, and Yaroshetskil ID (1993) Anomalous photoluminescene polarization of porous silicon. JETP Lett. 58, 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovalev D, Ben-Chorin M, Diener J, Averboukh B, Polisski G, and Koch F (1997) Symmetry of the electronic states of Si nanocrystals: An experimental study. Phys. Rev. Lett 79(1), 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch F, Kovalev D, Averboukh B, Polisski G, and Ben-Chorin M (1996) Polarization phenomena in the optical properties of porous silicon. J. Luminesc 70, 320–332. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamarro M, Gourdon C, Lavallard P, and Ekimov AI (1995) Enhancement of exciton exchange interaction by quantum confinement in CdSe nanocrystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys 34, 12–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bawendi MG, Carroll PJ, Wilson WL, and Brus LE (1992) Luminescence properties of CdSe quantum crystallites: Resonance between interior and surface localized states. J. Chem. Phys 96(2), 946–954. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gafni A, and Brand L (1978) Excited state proton transfer reactions of acridine studied by nanosecond fluorometry. Chem. Phys. Lett 58, 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lakowicz JR, and Balter A (1982) Theory of phase-modulation fluorescence spectroscopy for excited state processes. Biophys. Chem 16, 99–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lakowicz JR, and Balter A (1982) Detection of the reversibility of an excited state reaction by phase modulation fluorometry. Chem. Phys. Lett 92, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lakowicz JR (1999) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed., Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spichiger-Keller UE (1998) Chemical Sensors and Biosensors for Medical and Biological Applications, Wiley-VCH, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lakowicz JR, Soper SA, and Thompson RB (1999) Proceedings of Advances in Fluorescence Sensing Technology IV, SPIE Proc., San Jose, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfbeis OS (Ed.). (1991) Fiber Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors, Vol. I, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolfbeis OS (Ed.). (1991) Fiber Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors, Vol. II, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Czarnik AW (Ed.). (1992) Fluorescent Chemosensors for Ion and Molecule Recognition, ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 538, Am. Chem. Soc, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lakowicz JR (Ed.). (1994) Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 4: Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]