Abstract

Objective

To address the frequency of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody (Ab) in an unselected large cohort of adults with MS.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study in 2 MS expert centers (Lyon and Strasbourg University Hospitals, France) between December 1, 2017, and June 31, 2018. Patients aged ≥18 years with a definite diagnosis of MS according to 2010 McDonald criteria were tested for MOG-Ab by using a cell-based assay (CBA) in Lyon and subsequently included. Positive samples were tested by investigators blinded to the first result with a second assay in a different laboratory (Barcelona, Spain) by using the same plasmid and secondary Ab.

Results

Serum samples from 685 consecutive patients with MS were analyzed for MOG-Ab. Median disease duration at sampling was 11.5 (interquartile range, 5.8–17.7) years, and 72% were women. Two (0.3%) patients resulted to be MOG-Ab-positive. The 2 patients were women aged 42 and 38 at disease onset and were diagnosed with secondary and primary progressive forms of MS, respectively. This positive result was confirmed by the CBA in Barcelona.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that MOG-Ab are exceptional in MS phenotype, suggesting that the MOG-Ab testing should not be performed in typical MS presentation.

In adults, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies (Ab) are mainly found in patients with a neuromyelitis optica clinical phenotype, i.e., optic neuritis (ON) or myelitis isolated or in combination.1

A recent review pooling patients from all available MOG-Ab studies found that 24 of 1,608 (1.5%) and 105 of 1771 (6%) patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MS had MOG-Ab by using cell-based assays (CBAs) with immunofluorescence or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), respectively.2 However, the sample size of patients with MS included as controls in these studies is limited, patients were usually preselected, and most importantly, such studies have not been designed to ascertain the specific value of MOG-Ab in patients with a definite diagnosis of MS.3–6 Thus, to draw definitive conclusions about antibody, specificity should be prevented. The only study aimed at determining the frequency of MOG-Ab in MS included 200 selected patients with MS, all primary or secondary progressive forms, and all tested negative.7 Therefore, whether MOG-Ab can be present in MS and in what proportion has never been precisely evaluated.

In the present study, we addressed the frequency of MOG-Ab in a large sample of unselected patients with MS using a highly specific assay.

Methods

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional study in 2 MS expert centers (Lyon and Strasbourg University Hospitals, France) between December 1, 2017, and June 31, 2018. All patients aged ≥18 years with a definite diagnosis of MS according to 2010 McDonald criteria. Patients included were visited consecutively as part of their routine clinical practice in the day care unit.8

Clinical information was provided in specific case report forms by a neurologist with expertise in neuroinflammatory disorders and entered in the Eugene Devic Foundation against Multiple Sclerosis (EDMUS) database.9 Demographic data (sex and Caucasian ethnicity) and age at the onset of disease and disease duration at sampling were collected. MS disease subtype (clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting, secondary or primary progressive MS) was also reported. Relapses within the month before sampling, as well as corticosteroids and disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) at the time of sampling, were collected. Patients on anti-CD20 were considered on-treatment in the 6 months after the last infusion. Medical charts of MOG-Ab-positive cases were reviewed in detail by expert clinicians (A.C.-C., R.M., and J.D.S.).

Live CBAs

HEK293 cells were transfected with pEGFP-N1-hMOG plasmid. Serum samples were used at a dilution of 1:640. Allophycocyanin-Goat IgG-Fcγ fragment-specific was used as a secondary antibody and signal intensity evaluation was performed with FACS. As recommended,10 positive samples were tested by investigators blinded to the first result with a second assay in Barcelona by using the same plasmid and secondary antibody4 (supplementary data, links.lww.com/NXI/A169).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

All participants included in the present study belong to the national French registry designated as Observatoire Français de la Sclérose En Plaques9 and signed informed consent to have their medical data collected in routine practice used after anonymization and aggregation for research purposes. MOG-Ab were performed as part of the clinical routine evaluation; thus, no other specific consent was required.

Data availability

Anonymized data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Results

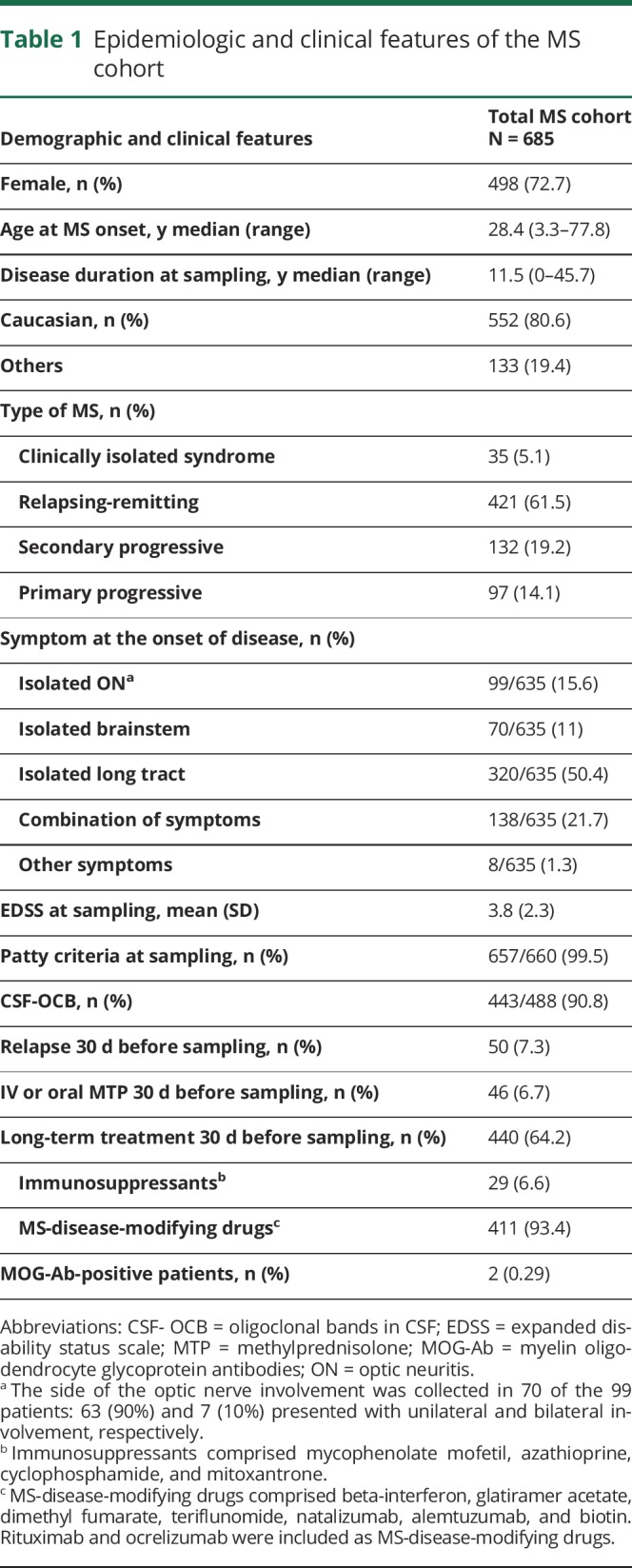

Serum samples from 685 patients with MS were analyzed for MOG-Ab during the period of this study. The median age at disease onset was 28.4 (interquartile range [IQR], 22.1–37.2) years, and the median disease duration at sampling was 11.5 (IQR, 5.8–17.7) years. Seventy-two per cent were women, and 80.6% Caucasians (table 1). Fifty (7.3%) patients had relapsed within the month before sampling. Forty-six (6.7%) and 440 (64.2%) had received corticosteroids and DMTs within the month previous to sampling, respectively. Additional characterization of the MS cohort is depicted in table 1 and table e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A171.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic and clinical features of the MS cohort

Two (0.3%) female patients, aged 42 and 38 at MS onset, were found MOG-Ab-positive after 26 and 11 years of disease duration, respectively. One patient was diagnosed with a secondary progressive MS and the other with a primary progressive MS, with no history of ON or myelitis. Clinical information of MOG-Ab-positive patients is shown in table 2 and figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A170.

Table 2.

Clinical features of patients with MS with positive MOG-Ab

Discussion

n the present cohort of unselected definite patients with MS, only 2 (0.3%) were found MOG-Ab-positive, among 685 patients tested.

Differential diagnosis at the onset of disease in patients with MOG-Ab-positive and in those with MS is challenging because a proportion may present with overlapping features, i.e., ON involvement, short myelitis, or MS-like brain lesions. Such an overlap raises the question of whether patients with MS should be tested widely for MOG-Ab. The use of accurate antibody assays is highly recommended to discriminate true positive cases. Currently, live CBA using human full-length MOG and restricting with IgG1 or IgG-Fcγ fragment-specific as a secondary antibody is the most accurate detection method.10 By using these techniques, we achieved full agreement between Lyon and Barcelona laboratories. Both centers used similar approaches except for the antibody lecture: FACS in Lyon and immunocytochemistry in Barcelona.

The present study was conducted by 2 French referral centers for neuroinflammatory disorders that follow internationally well-validated criteria for MS diagnosis and have a recognized expertise in other less frequent CNS demyelinating diseases. Therefore, if we consider this high clinical sensibility to discriminate rare diseases from typical MS and the fulfillment of 2010 McDonald criteria in all the patients included, we could assume that the 2 MOG-Ab-positive patients yielded a false positive result. Indeed, both patients had no typical symptoms of MOG-Ab-associated disease1 but a genuine progressive phenotype with typical MS features. Our results are in line with those recently obtained by the Oxford and Mayo group displaying 100% and 99.6% of specificity, respectively, although a preselected MS cohort was included in this study.6 The only study evaluating the frequency of MOG-Ab in progressive MS did not find any positive result by using a similar method than us.7 However, this is the first study focused on different MS subtypes whose major strength lies on the large sample size allowing for a well-powered investigation. Therefore, the absence of a positive result in 99.7% of patients with typical MS together with the agreement of the results between centers in the MOG-Ab-positive cases supports the high specificity of the antibody testing methodology.

Certain limitations must be addressed. MOG-Ab titers may vary depending on the phase of the disease being higher during relapse and lower in the remission phase.1 This fluctuation over time may underestimate the real frequency of MOG-Ab and increase the risk of false negative result when performing cross-sectional studies. Moreover, corticosteroids or long-term treatment might also have an influence over titers.

In conclusion, the present study revealed low (0.3%) frequency for MOG-Ab positivity in patients with MS by using highly specific assays. Our results have important clinical implications for neurologists in daily clinical practice, and we do not recommend MOG-Ab testing in patients with MS fulfilling 2010 McDonald criteria, with typical features.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Albert Saiz (Center of Neuroimmunology, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain) for having performed different antibody testing. The authors thank the group of NeuroBioTec from Hôpital Civils de Lyon for supporting this study.

Glossary

- Ab

antibody

- CBA

cell-based assay

- DMT

disease-modifying treatment

- EDMUS

Eugene Devic Foundation against Multiple Sclerosis

- IQR

interquartile range

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- NMO

neuromyelitis optica

- OFSEP

Observatoire Français de la Sclérose En Plaques

- ON

optic neuritis

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was conducted using data from the Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP), which is supported by a grant provided by the French State and handled by the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche,” within the framework of the “Investments for the Future” program, under the reference ANR-10-COHO-002 Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP), the EDMUS Foundation, and Déchaine Ton Coeur.

Disclosure

F. Durand-Dubief serves on a scientific advisory board for Merck Serono and has received funding for travel and honoraria from Biogen, Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, Roche, and Teva Pharm. S. Vukusic has received consulting and lecturing fees, travel grants, and research support from Biogen, GeNeuro, Genzyme, Novartis, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and Teva Pharm. R. Marignier has received consulting and lecturing fees, travel grants, and research support from Bayer-Schering, Biogen, Idec, Genzyme, Novartis, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva Pharma. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures

References

- 1.Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Maillart E, et al. Clinical spectrum and prognostic value of CNS MOG autoimmunity in adults: the MOGADOR study. Neurology 2018;90:e1858–e1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reindl M, Waters P. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Kleiter I, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 1: frequency, syndrome specificity, influence of disease activity, long-term course, association with AQP4-IgG, and origin. J Neuroinflammation 2016;13:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Höftberger R, Sepulveda M, Armangue T, et al. Antibodies to MOG and AQP4 in adults with neuromyelitis optica and suspected limited forms of the disease. Mult Scler 2015;21:866–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacohen Y, Absoud M, Deiva K, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies are associated with a non-MS course in children. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2:e81. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters PJ, Komorowski L, Woodhall M, et al. A multicenter comparison of MOG-IgG cell-based assays. Neurology 2019;92:e1250–e1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Stellmann JP, et al. MOG-IgG in primary and secondary chronic progressive multiple sclerosis: a multicenter study of 200 patients and review of the literature. J Neuroinflammation 2018;15:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vukusic S, Casey R, Rollot F, et al. Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP): A unique multimodal nationwide MS registry in France. Mult Scler Epub 2018 Dec 13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Jarius S, Paul F, Aktas O, et al. MOG encephalomyelitis: international recommendations on diagnosis and antibody testing. J Neuroinflammation 2018;15:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data can be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.