Abstract

Objective

To determine whether basing the decision to initiate immediate vs delayed disease-modifying therapy (DMT) on extent of recovery after initial relapse affects long-term disability accumulation in a multiple sclerosis (MS) evidence-based setting.

Methods

We analyzed the double-blind, placebo-controlled interferon beta-1a 30 mc once a week in clinically isolated syndrome and 10-year-follow-up extension trial. Good recovery after presenting relapse was defined as (1) full early recovery within 28 days of symptom onset (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] score of 0 at enrollment maintained ≥6 months) and (2) delayed good recovery (EDSS score > 0 at enrollment and improvement from peak deficit to 6th-month or 1-year visit ≥ median). Time from recovery assignment to future disability (EDSS score ≥ 2.5 or ≥4.0) was studied on a relapse-recovery-stratified age axis and immediate vs 3-year delayed treatment initiation with Kaplan-Meier statistics and hazard ratios (HRs).

Results

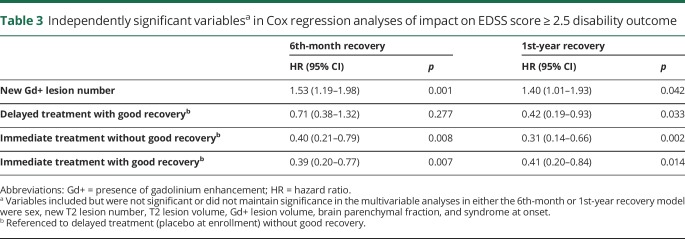

One hundred seventy-five/328 patients had good recovery (94 immediate and 81 delayed treatment); 153 did not have good recovery (77 immediate and 76 delayed treatment). HRs for EDSS score ≥2.5 outcome were: delayed treatment without good recovery as reference (HR = 1.0), delayed treatment with good recovery (HR6th-month: 0.67, p = 0.207; HR1st-year: 0.40, p = 0.027), immediate treatment without good recovery (HR6th-month: 0.56, p = 0.061; HR1st-year: 0.40, p = 0.011), and immediate treatment with good recovery (HR6th-month: 0.43, p = 0.014; HR1st-year: 0.48, p = 0.034). Placebo patients were switched to long-term treatment after 3 years, and insufficient EDSS score ≥4.0 outcome events were available to study.

Conclusions

In patients with MS presenting without good recovery after the initial relapse, immediate DMT initiation favorably influences the likelihood of more ambulatory-benign disease akin to patients with good recovery after the initial relapse.

Classification of evidence

This study provides Class III evidence that for patients with MS without good recovery after the initial relapse, immediate DMT initiation increases the likelihood of a benign disease course.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), partial recovery from relapses leads to residual disability.1 Limited recovery from early clinical relapses also situates patients with MS for an earlier onset of progressive disease.2 A single, partially recovered, symptomatic or asymptomatic, critically located lesion in the high cervical spinal cord is sufficient to set a patient up for progressive disease.3,4 Despite this critical role of relapse recovery in long-term prognosis in MS, relapse recovery has not been sufficiently modeled into clinical trials in early MS. Few studies have used relapse recovery as an outcome measure hypothesizing that disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) will help recovery from ensuing relapses after treatment initiation.5,6 A common real-world practice in deciding immediate vs delayed DMT initiation in early MS often involves the extent and rapidity of a patient's recovery from early relapses, a decision for which there is no evidence from a clinical trial setting.

Relapse recovery worsens as a patient gets older.1,7–11 Recovery from early relapses seems to be similar within an individual patient, pointing to individual specific factors responsible for a “good” vs “poor” recovery paradigm.2 In a population-based cohort, we recently showed that when controlling for inherent individual factors by paired analyses of early and late relapses from the same patient, there is a relatively linear decline in clinical recovery after a relapse with aging.12 We also showed that improvement from the maximum disability reached during the first clinically evident relapse (i.e., clinically isolated syndrome [CIS]) can be measured by a change in the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score as a clinically useful metric of recovery.12

Age of a patient is also a critical factor in developing progressive MS, which peaks around the fifth decade.13–15 The same decade coincides with a pathologic shift to smoldering plaques associated with the progressive phase in MS.16 DMT efficacy declines with older age,17 likely reflecting a natural decrease in relapses with age, a natural increase in progressive MS with age but also the natural decline in relapse recovery potential with age. This lower endogenous recovery potential later in life makes it easier to observe a change with exogenous recovery intervention in older patients in a clinical trial setting.18

To understand the interaction between relapse recovery and DMT efficacy and given the impact of early relapses on long-term outcome in MS, the best approach would be a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in CIS with stratification by relapse recovery at enrollment. However, use of DMTs in CIS and early MS is a well-established practice, and the feasibility of a future longitudinal trial could be challenging for recruiting sufficient size of an untreated population with CIS.

We used a unique opportunity to analyze the clinical and imaging data from the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Interferon beta-1a 30 mc once a week (Avonex) in CIS and its 10-year follow-up extension.19,20 These studies originally established the benefit of DMTs in delaying further relapses after a CIS event. We studied the interaction of relapse recovery at the time of CIS with immediate vs delayed initiation of Avonex in determining long-term disability worsening.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

All patients originally consented for the Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study (CHAMPS) and Controlled High-Risk Avonex® MS Prevention Study in Ongoing Neurological Surveillance (CHAMPIONS).19,20 No patient identifiers were available for the current analyses.

Study population

CHAMPS was a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of IM interferon beta-1a in patients with CIS.14 At the time of original enrollment, patients' ages ranged from 18 to 50 years, and all had experienced a unilateral optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, or brainstem-cerebellar syndrome. The baseline requirement was ≥2 additional asymptomatic brain lesions with typical characteristics of an MS lesion. All patients received 3 days of 1 g IV methylprednisolone per day followed by a 15-day oral prednisone taper within 14 days of onset of their symptoms. All patients got randomized to treatment (30 μg of IM interferon beta-1a, N = 193) or placebo (N = 190) arms within 27 days of symptom onset. The CHAMPS study period was 3 years. Ninety-three percent of patients on the original active treatment arm and 99.5% of patients on the original placebo arm complied with drug dosing over 80% of the time.14,15

The CHAMPIONS was a 2-phase extension study.15 After the completion of the CHAMPS, all patients were offered active treatment for an additional 2 years to complete 5 years. In the second extension phase, all patients were offered an additional 5 years of active treatment to complete 10-year follow-up. The goal was to assess the impact of immediate treatment initiation (10 years active treatment) vs delayed treatment initiation (3 years placebo +7 years active treatment) on long-term disability outcome.

Definition of clinical variables

The presenting relapse was defined as originally described in the clinical trial setting.14 However, some of these patients would have been classified as relapsing-remitting MS with contemporary diagnostic criteria, which appeared after the original study design.21 Therefore, we refer to the original event as the initial relapse rather than CIS.

Degree of clinical recovery was defined as the improvement from the peak deficit of a relapse to stabilized baseline after at least 6 months, a conservative time frame, because most recovery takes place within the first 3 months or less.1,22,23 Based on our recent publication,12 we chose to use the improvement in the EDSS score as our clinical recovery metric appropriate for our analyses. Because we studied the initial relapse, all patients were assumed to have an EDSS score of 0 before the index event. We took the EDSS score at enrollment, which was recorded within 28 days of symptoms onset, as representative of the peak deficit associated with the initial relapse.

Good recovery from the initial relapse is defined as fulfilling one of the 2 following criteria: (1) when the peak deficit at enrollment within the 28 days of symptom onset is the EDSS score of 0 and the EDSS score of 0 is maintained through the 6th-month visit, the patient is assumed to have already recovered fully at enrollment, or (2) when the peak deficit at enrollment within the 28 days of symptom onset is EDSS score >0, the patient is assumed to have good recovery if the EDSS score improvement from peak deficit to 6th-month visit was equal to or better than the median of the group. We used median over mean values, as the EDSS is a composite ordinal scale, and further categorical definitions of good vs not good recovery were introduced. Given that some patients did not have 6th-month visits, we also repeated the analyses by using the 1st-year visit to assign good recovery.

Data analyses

We tested the hypothesis that patients with insufficient recovery with delayed DMT initiation do worse than patients with insufficient recovery and immediate DMT initiation or patients with good recovery regardless of timing of DMT initiation. This study provides Class III evidence that for patients with MS without good recovery after the initial relapse, immediate DMT initiation increases the likelihood of a benign disease course.

Baseline demographics and clinical, imaging, and recovery metrics were compared between immediate vs delayed treatment groups using the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test, linear model analysis of variance, trend test for ordinal variables, or Pearson χ2 test as appropriate to the variable. We studied 2 long-term disability outcomes: (1) reaching an EDSS score of 2.5 or higher or (2) reaching an EDSS score of 4.0 or higher. Time from assigning recovery status (6 months or 1 year from enrollment) to reaching EDSS outcomes was studied and shown on an age axis initially stratified for immediate vs delayed treatment groups. The analyses were repeated further stratifying each intervention group by the relapse recovery metric. Kaplan-Meier statistics were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and CIs for relapse recovery treatment interaction variables, using the worst outcome group as reference. Finally, we studied the independence of our observations by Cox regression analyses including baseline demographics, baseline clinical characteristics, baseline radiologic characteristics, and the relapse recovery and intervention groups. We report additional HRs and CIs for variables that remained independently significant in the Cox regression analyses.

Data availability

All data from the original CHAMPS and CHAMPIONS trials were made available for analyses without any constraints.

Results

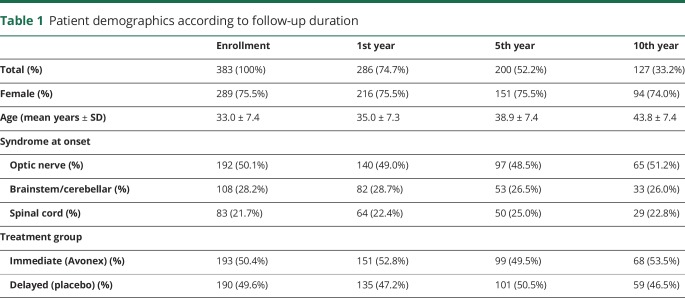

In table 1, we recapitulate the demographics of the study population according to years from initial enrollment. We noted no shift in distribution of baseline characteristics of patients according to years of follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient demographics according to follow-up duration

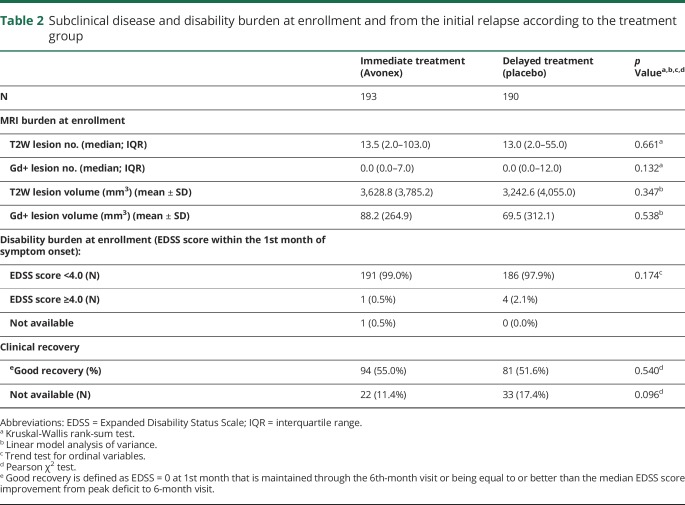

In table 2, we show subclinical disease burden at enrollment, disability burden at enrollment, and initial relapse recovery according to the intervention group. Except for a previously known (from the original published studies) difference in brain parenchymal fraction, there were no differences between intervention groups regarding baseline characteristics.

Table 2.

Subclinical disease and disability burden at enrollment and from the initial relapse according to the treatment group

Of the 383 patients at enrollment, 55 (22 immediate treatment and 33 delayed treatment) did not have the EDSS score recorded. Of the remaining 328 patients, at the time of enrollment within 28 days of their initial relapse event, 114 (56 immediate treatment and 58 delayed treatment) had an EDSS score of 0, and 214 had an EDSS score of >0.

Of the 114 patients who had EDSS score = 0 at enrollment, 57 remained EDSS score = 0 at 6 months, therefore established as having already fully recovered within the first 28 days before enrollment. Of the 214 patients with EDSS score > 0 at enrollment, 118 patients had an EDSS score improvement ≥1 point from peak deficit to 6th-month visit. Therefore, at the 6th month from enrollment, we were able to qualify 175 patients (57 + 118) as having good recovery (94 immediate treatment and 81 delayed treatment) and 153 patients as not having good recovery (77 immediate treatment and 76 delayed treatment—table 2).

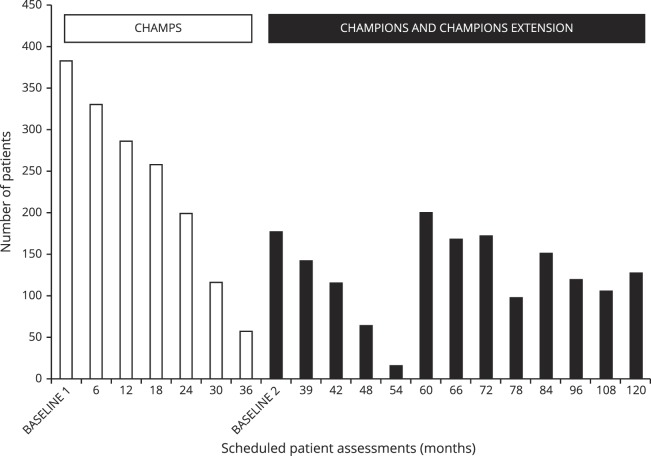

The number of patients available for scheduled follow-up visits is shown in figure 1. Between all phases of the study, 171 patients were seen 6 times, and 155 patients were seen 12 times. There were a total of 2,940 EDSS measurements to establish disability accrual through the study. The median EDSS score throughout the study was 1.0 (minimum 0.0–maximum 8.0).

Figure 1. Number of patients available for scheduled patient assessments in CHAMPS, CHAMPIONS, and CHAMPIONS extension illustrating repeat enrollment with rerecruitment of patients lost to follow-up during previous phases.

CHAMPIONS = Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study in Ongoing Neurological Surveillance; CHAMPS = Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study.

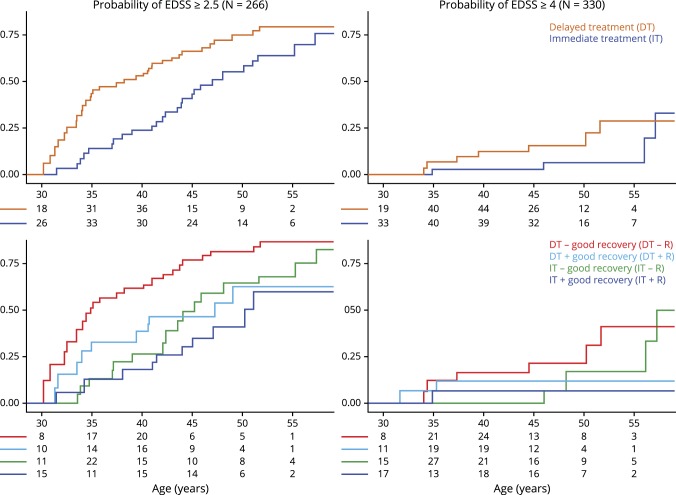

Patients who did not have a 6th-month visit and those who had already reached the disability outcome within the first 6 months and sustained it later were excluded, leaving 266 patients for EDSS score ≥2.5 outcome and 330 patients for EDSS score ≥ 4.0 outcome analyses. For the second model of 1st-year visit to assign good recovery, we had 229 patients for EDSS score ≥ 2.5 outcome and 265 patients for EDSS score ≥ 4.0 outcome analyses (figure 2).

Figure 2. Probability of long-term disability accumulation along the age axis is shown.

Groups are defined according to good recovery from the initial relapse at 6th-month and treatment intervention. Figure is shown with the age axis started and truncated at the point where every analysis group is still required to have ≥1 patient in the study. Patients with good recovery and immediate initiation of DMT after their first relapse have about 65% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level of EDSS score <2.5 by age 45 years. On the other hand patients with poor recovery and delayed DMT initiation have about 20% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level by age 45 years. Patients with poor recovery but immediate DMT initiation have about 50% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level by age 45 years similar to patients with good recovery but delayed DMT initiation. CHAMPS = Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study; CHAMPIONS = Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study in Ongoing Neurological Surveillance; DT = delayed treatment with randomization to placebo at CHAMPS enrollment with switch to disease-modifying therapy (DMT) with Avonex at CHAMPIONS enrollment; IT = immediate treatment with randomization to Avonex at CHAMPS enrollment and maintained on DMT throughout CHAMPIONS; good recovery is defined as EDSS score = 0 at 1st month that is maintained through the 6th-month visit or being equal to or better than the median EDSS score change from peak deficit to 6-month visit.

EDSS score ≥ 2.5 outcome

We used the worst combination outcome of delayed treatment without a good initial relapse recovery as our reference (HR = 1.0). Using the 6th-month visit to define good recovery, the delayed treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.67 (95% CI [0.36–1.25], p = 0.207), the immediate treatment without the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.56 (95% CI [0.31–1.03], p = 0.061), and the immediate treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.43 (95% CI [0.22–0.84], p = 0.014).

Using the same reference of delayed treatment without a good initial relapse recovery, but 1st-year visit to define good recovery, the delayed treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.40 (95% CI [0.18–0.90], p = 0.027), the immediate treatment without the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.40 (95% CI [0.20–0.81], p = 0.011), and the immediate treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group had an HR of 0.48 (95% CI [0.24–0.94], p = 0.034).

These findings were maintained independently in the multivariable Cox regression analyses (table 3). For the EDSS score ≥2.5 outcome, the delayed treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group, the immediate treatment without the good initial relapse recovery group, and the immediate treatment with the good initial relapse recovery group maintained their independent positive effect compared with delayed treatment without a good initial relapse recovery.

Table 3.

Independently significant variablesa in Cox regression analyses of impact on EDSS score ≥ 2.5 disability outcome

The presence of gadolinium-enhancing lesions at enrollment had a negative impact on disability outcome independent of relapse recovery treatment interaction variable.

EDSS score ≥ 4.0 outcome

In this analysis, although we found HRs to be similar to EDSS score ≥2.5 outcome analysis, event rates were low (as shown in figure 2), and the results did not reach statistical significance in either 6th-month or 1st-year definitions of recovery in univariate or multivariable analyses (data not shown).

Discussion

We provide, to our knowledge, the first clinical trial evidence to support the practice of deciding immediate vs delayed DMT initiation in early MS based on how poorly a patient recovers from their initial relapse. Based on our study, following practical numbers can be summarized: patients with good recovery and immediate initiation of DMT after their first relapse have ∼65% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level by age 45 years. On the other hand, patients with poor recovery and delayed DMT initiation have ∼20% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level of EDSS score <2.5 by age 45 years. Patients with poor recovery but immediate DMT initiation or patients with good recovery but delayed DMT initiation similarly have ∼50% chance of remaining at a minimal disability level of EDSS score <2.5 by age 45 years. Therefore, delaying initiation of DMTs, especially after a poorly recovered relapse, further hampers the likelihood of remaining relatively disability-free by critical age 45 years, beyond which there is a higher likelihood of developing progressive MS.13–15 Although the study focused on a single DMT, it would be reasonable for such analyses to be conducted in other DMT trials in CIS setting.

As we had recently shown the impact of aging on relapse recovery with the clinical relapse recovery metrics in a population-based cohort,12 we used age rather than time from disease onset for modeling relapse recovery and treatment interaction in MS. Without our recent findings, such modeling would have been premature at the time of original CHAMPS trial design, and it seems timely that we have carried our findings from the population-based, natural history study to a clinical trial setting now.

Choice of disability cutoffs in our study was dictated by the availability of data in a trial setting as opposed to natural history studies. Given that all patients were placed on DMT throughout the extension phase of the trial, event rates for moderate-to-severe disability levels were low. Our hypothesis dictated that any interaction between good relapse recovery and immediate treatment should result in benign outcomes. The clinical trial standard in MS has been the EDSS as is which was available for us to use in our analyses. Maintaining an EDSS score of <2.5 is generally accepted as having an ambulatory-benign MS while clearly not reflecting cognitive dysfunction that may still occur.24 However, most practicing and academic MS specialists would agree that maintaining a mild disability level or better (≤EDSS score 2.5) is generally accepted as a benign disease course in MS. Hence, our chosen primary outcome of EDSS score 2.5 cutoff was a good match for testing our hypothesis.

We also explored EDSS4 as a cutoff. As patients who reach EDSS4 have a more linear disability accumulation afterward,25–27 using EDSS4 gave us a window into the future of moderate-to-severe disability accumulation in the study groups. However, using the EDSS4 cutoff, there were insufficient events in our analyses as shown in figure 2, reasonably consistent with the premise that early initiation of DMTs in MS delays moderate-to-severe disability, likely through delaying further clinical and radiologic events.

Another challenge related to using the EDSS score both as an outcome and as a relapse recovery metric. We have recently shown that it is suitable to use the EDSS score to measure recovery after the first clinical relapse in MS.12 In an ideal study design, patients should be enrolled in a treatment arm after the recovery is given sufficient time to stabilize before assigning good vs poor recovery. Because the CHAMPS17 was designed without this metric in mind, we had only 1 month after the index relapse and before the randomization. Therefore, we had to compromise at several levels. We accepted as “already recovered” anyone with an EDSS0 at the time of randomization and who maintained that level at the time of 6th-month or 1st-year recovery assessment. On the other hand, we excluded patients who had already reached and thereafter maintained the outcome measure at the time of randomization (i.e., EDSS2.5 or EDSS4.0) from the study because any recovery afterward would potentially be biased by the active arm of the trial. Although we recognize a lack of definitive evidence for the possibility of DMT impact on relapse recovery, using a similar metric of EDSS change as our study to assess recovery outcome in MS, patients on natalizumab treatment attained a less severe peak deficit during a subsequent relapse than patients on placebo, and, expectedly, patients on natalizumab achieved better recovery than placebo at the 6-month time point.5 In another post hoc study using the EDSS metric as above, patients treated with peginterferon beta-1A had better 6th-month postrelapse recovery while on treatment than those who received placebo.6 These studies suggest that DMTs, potentially through a dampening effect on the peak severity of a relapse, improve odds of recovery from that relapse. Of interest, in our study, although the 1st-year relapse recovery assessment captured an independent positive effect of good recovery despite delayed treatment, the 6th-month assessment did not. This observation could support the hypothesis of a modest impact of early DMT initiation on overall relapse recovery even if initiated after a relapse.

Our good recovery definition was based on a median EDSS score change, which can be fine tuned in a future study by good, average, or poor recovery if functional system scores are used to assess recovery.2,12 Unfortunately, we did not have raw functional system scores available from the time of enrollment in this trial.

Finally, we observed that having subclinical active disease, as evidenced by baseline active MRI findings, affected disability outcome independently of relapse recovery treatment interaction variables. However, in this study, follow-up imaging or electrophysiology-based recovery metrics were not collected specifically to assess subclinical improvement in patients, limiting our analyses to clinical recovery metrics alone. As it has been illustrated in the RENEW trial with Opicinumab (anti-LINGO-1) in acute optic neuritis (NCT01721161), where recovery was the actual outcome measure, subclinical recovery assessment exemplified by full-field visual evoked potential latency was found relevant as a potential confounder of outcome.18 Therefore, we suggest that inclusion of such subclinical metrics of recovery also be considered in a definition of good-versus-poor recovery stratification at enrollment in addition to clinical recovery metrics.

A better understanding of the biology underlying relapse recovery in MS is of utmost importance in generating better animal models of recovery, in developing better recovery agents, in more optimal timing of administration of recovery agents in future recovery trials, and in defining the clinical/subclinical metrics appropriate for the recovery measurement. At the moment, several such agents are moving along different phases of development and clinical trials.18,28 Our current analyses, together with our previous observation that a poor early relapse recovery significantly shortens the time to progressive MS onset,2 raise awareness of the importance of relapse recovery as a predictive factor of long-term outcomes in MS.

Approaches to promote remyelination to prevent long-term progression should be initiated early in the disease course at the time of the first or second relapse. For example, a successful remyelinating therapy used to return disability back to normal during a relapse might prevent long-term progression, likely by protecting axons through ensheathment.29

In summary, we believe that the analyses presented in this work support 2 important findings about relapse recovery: first, that it should be a variable controlled at inclusion in clinical trials, and second, that it should be an early decision factor for DMT initiation. Because relapse recovery independently influences long-term disease outcomes, we recommend that it be assessed routinely as part of MS clinical trials with more precisely timed EDSS and FSS measurements around the clinical relapses. It is very likely that DMTs and medications stimulating relapse recovery will be used concomitantly, and clinical or subclinical metrics that can assess such interactions will be further relevant in future clinical trials.

Glossary

- CHAMPIONS

Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study in Ongoing Neurological Surveillance

- CHAMPS

Controlled High-Risk Avonex MS Prevention Study

- CIS

clinically isolated syndrome

- HR

hazard ratio

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Study funding

This study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Biogen to O.H. Kantarci.

Disclosure

O.H. Kantarci received salary support as part of the grant from Biogen during the period of the study. B. Zeydan reports no disclosures. E.J. Atkinson received salary support as part of the grant from Biogen during the period of the study. B.L. Conway reports no disclosures. C. Castrillo-Viguera is employed by Biogen. M. Rodriguez reports no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Lublin FD, Baier M, Cutter G. Effect of relapses on development of residual deficit in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2003;61:1528–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novotna M, Paz Soldán MM, Abou Zeid N, et al. Poor early relapse recovery affects onset of progressive disease course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015;85:722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keegan BM, Kaufmann TJ, Weinshenker BG, et al. Progressive solitary sclerosis: gradual motor impairment from a single CNS demyelinating lesion. Neurology 2016;87:1713–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keegan BM, Kaufmann TJ, Weinshenker BG, et al. Progressive motor impairment from a critically located lesion in highly restricted CNS-demyelinating disease. Mult Scler 2018;24:1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lublin FD, Cutter G, Giovannoni G, Pace A, Campbell NR, Belachew S. Natalizumab reduces relapse clinical severity and improves relapse recovery in MS. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014;3:705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott TF, Kieseier BC, Newsome SD, et al. Improvement in relapse recovery with peginterferon beta-1a in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2016;2:2055217316676644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cossburn M, Tackley G, Baker K, et al. The prevalence of neuromyelitis optica in South East Wales. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fay AJ, Mowry EM, Strober J, Waubant E. Relapse severity and recovery in early pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012;18:1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leone MA, Bonissoni S, Collimedaglia L, et al. Factors predicting incomplete recovery from relapses in multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Mult Scler 2008;14:485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowry EM, Pesic M, Grimes B, Deen S, Bacchetti P, Waubant E. Demyelinating events in early multiple sclerosis have inherent severity and recovery. Neurology 2009;72:602–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarci O, Siva A, Eraksoy M, et al. Survival and predictors of disability in Turkish MS patients. Turkish Multiple Sclerosis Study Group (TUMSSG). Neurology 1998;51:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway BL, Zeydan B, Uygunoglu U, et al. Age is a critical determinant in recovery from multiple sclerosis relapses. Mult Scler 2019;25:1754–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Natural history of multiple sclerosis: a unifying concept. Brain 2006;129:606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, De Keyser J. Progression in multiple sclerosis: further evidence of an age dependent process. J Neurol Sci 2007;255:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tutuncu M, Tang J, Zeid NA, et al. Onset of progressive phase is an age-dependent clinical milestone in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frischer JM, Weigand SD, Guo Y, et al. Clinical and pathological insights into the dynamic nature of the white matter multiple sclerosis plaque. Ann Neurol 2015;78:710–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol 2017;8:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cadavid D, Balcer L, Galetta S, et al. Predictors of response to opicinumab in acute optic neuritis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1154–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;343:898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinkel RP. Interferon-beta1a: a once-weekly immunomodulatory treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2006;2:691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vercellino M, Romagnolo A, Mattioda A, et al. Multiple sclerosis relapses: a multivariable analysis of residual disability determinants. Acta Neurol Scand 2009;119:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollmer T. The natural history of relapses in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2007;256(1 suppl):S5–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittock SJ, McClelland RL, Mayr WT, et al. Clinical implications of benign multiple sclerosis: a 20-year population-based follow-up study. Ann Neurol 2004;56:303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, Adeleine P. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1430–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Adeleine P. Early clinical predictors and progression of irreversible disability in multiple sclerosis: an amnesic process. Brain 2003;126:770–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E, et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2010;133:1900–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wootla B, Watzlawik JO, Warrington AE, et al. Naturally occurring monoclonal antibodies and their therapeutic potential for neurologic diseases. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1346–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wootla B, Denic A, Watzlawik JO, Warrington AE, Rodriguez M. Antibody-mediated oligodendrocyte remyelination promotes axon health in progressive demyelinating disease. Mol Neurobiol 2016;53:5217–5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data from the original CHAMPS and CHAMPIONS trials were made available for analyses without any constraints.