Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that interactions among proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and cancer cell–recruited neutrophils result in enhanced metastasis and chemotherapy resistance. Nonetheless, the detailed mechanism remains unclear. Our aim was to discover the role of IL-17, CXC chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) ligands, and cancer-associated neutrophils in chemotherapy resistance and metastasis in breast cancer. Mice were injected with Cl66 murine mammary tumor cells, Cl66 cells resistant to doxorubicin (Cl66-Dox), or Cl66 cells resistant to paclitaxel (Cl66-Pac). Higher levels of IL-17 receptor, CXCR2 chemokines, and CXCR2 were observed in tumors generated from Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells in comparison with tumors generated from Cl66 cells. Tumors generated from Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells had higher infiltration of neutrophils and T helper 17 cells. In comparison with primary tumor sites, there were increased levels of CXCR2, CXCR2 ligands, and IL-17 receptor within the metastatic lesions. Moreover, IL-17 increased the expression of CXCR2 ligands and cell proliferation of Cl66 cells. The supernatant of Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells enhanced neutrophil chemotaxis. In addition, IL-17–induced neutrophil chemotaxis was dependent on CXCR2 signaling. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the IL-17–CXCR2 axis facilitates the recruitment of neutrophils to the tumor sites, thus allowing them to play a cancer-promoting role in cancer progression.

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancer types for women globally. The American Cancer Society estimated 268,600 new breast cancer cases and 41,760 deaths from female breast cancer in the United States for 2019.1 The present systemic treatments for breast cancer patients include immunotherapy and chemotherapy.2 Currently, the most commonly used chemotherapy agents for breast cancer are paclitaxel and doxorubicin.3,4 Therapy-resistant cancer cells can promote tumor recurrence and reduce patients' survival.5 Moreover, resistant tumors tend to be highly malignant and metastatic.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Hence, there is an urgent need to understand the biology of chemotherapy resistance to improve survival for cancer patients.

Evidence suggests the tumor microenvironment, other than tumor cells themselves, plays an essential role in cancer progression.10,11 The differences between chemotherapy-resistant and chemotherapy-nonresistant tumor microenvironments may contribute to tumor aggressiveness.9 Multiple factors have been proposed to play crucial protumor progression roles, including IL-17, CXC chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) ligands, and cancer cell–recruited neutrophils.9,12,13 IL-17 (in particular IL-17A) is a proinflammatory cytokine, mainly produced by type 17 T helper (Th17) cells,14 and can promote tumorigenesis, tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance.12,15, 16, 17, 18 IL-17 exerts its protumorigenic roles through the activation of downstream signaling pathways, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase and NF-κB.18, 19, 20 IL-17 is also known to induce expression of CXCR2 ligands in multiple cancer types, including breast cancer.18,21

CXCR2 ligands (CXCL 1 to 3 and 5 to 8) are found to play protumor progression roles in various cancer types, including breast cancer, by promoting angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, and motility.9,22,23 CXCR2 ligands also mediate cancer metastasis by modulating the recruitment of neutrophils.13,24 We have previously shown that CXCR2 and its ligands are crucial for chemotherapy resistance.22 Simultaneously, an increase in the levels of CXCR2 ligands is a consequence of chemotherapy resistance. Knocking down CXCR2 in cancer cells enhanced the antitumor and antimetastatic therapeutic response.22 More evidence now indicates the cross talk between IL-17, CXCR2 ligands, and neutrophils correlates with poor survival for breast cancer patients.13,25,26 In the present study, we examined the hypothesis that the presence of a higher level of IL-17 in chemotherapy-resistant tumors results in the production of higher levels of CXCR2 ligands, thereby recruiting a higher number of neutrophils, which result in the promotion of cancer metastasis and chemotherapy resistance. Our present study illustrates the role of IL-17 in the up-regulation of CXCR2 ligands, leading to neutrophil recruitment, and the role of neutrophils in prochemotherapy resistance and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

The murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell lines C166, doxorubicin resistant (Cl66-Dox), paclitaxel resistant (Cl66-Pac), and 4T1 (6-thioguanine resistant),27,28 and the human cell line MDA-MB-231 were used. The details of the establishment of Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac are described in Sharma et al.9 In brief, for the maintenance of C166-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells, 500 nmol/L doxorubicin or 400 nmol/L of paclitaxel was added in the medium, respectively. 4T1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 media (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, and 0.08% gentamycin. MDA-MB-231, Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (Mediatech, Hendon, VA) with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% vitamins, 1% glutamine, and 0.08% gentamycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The promyelocytic leukemia line HL60 (catalog number CCL240; ATCC, Manassas, VA) was cultured in RPMI 1640 or Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) media (Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.08% gentamycin. Moreover, the differentiation of HL60 was induced by 1.3% dimethyl sulfoxide for 6 days.29 A murine promyelocytic cell line, MPRO Clone 2.1 (ATCC; CRL-11422) was cultured in IMDM media with 4 mmol/L l-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 10 ng/mL murine granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, and 20% heat-inactivated horse serum. The differentiation of MPRO Clone 2.1 cells to neutrophils was induced by 10 μmol/L all-trans retinoic acid.30 All of the cell lines were free of Mycoplasma, as determined by the MycoAlert Plus Mycoplasma Detection kit (Lonza, Rockland, ME) and pathogenic murine viruses. For cell line authentication, the Human DNA Identification Laboratory, University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE), performed the short tandem repeat tests.31 Cultures were maintained for no longer than 6 weeks after recovery from frozen stocks.

mRNA Expression Analysis

Quantitative RT-PCR method was performed to analyze gene expression. In brief, 2 to 5 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) primers. Murine Cxcr2, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Cxcl5, Cxcl7, Il17, Il17ra, and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) (for normalizing gene expression) expression, together with human IL23, IL6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and β-actin (for normalizing gene expression), were detected. Quantitative RT-PCRs were prepared using cDNA, iTaq Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), gene-specific primers (Table 1), and the BIO-RAD CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad). BIO-RAD CFX Manager software version 3.1 was used to run the analysis. Mean Ct values of the target genes were normalized to mean Ct values of the endogenous control, HPRT (mouse), or β-actin (human): −ΔCt = Ct (HPRT or β-Actin) − Ct (target gene).

Table 1.

Primer Sequence Used in This Study

| Gene | Primers sequence |

|---|---|

| Cxcr2 | F: 5′-CACCGATGTCTACCTGCTGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CACAGGGTTGAGCCAAAAGT-3′ | |

| Cxcl1 | F: 5′-TCGCTTCTCTGTGCAGCGCT-3′ |

| R: 5′-GTGGTTGACACTTAGTGGTCTC-3′ | |

| Cxcl2 | F: 5′-AGTGAACTGCGCTGTCAATG-3′ |

| R: 5′-TTCAGGGTCAAGGCAAACTT-3′ | |

| Cxcl3 | F: 5′-GCAAGTCCAGCTGAGCCGGGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-GACACCGTTGGGATGGATCGCTTT-3′ | |

| Cxcl5 | F: 5′-ATGGCGCCGCTGGCATTTCT-3′ |

| R: 5′-CGCAGCTCCGTTGCGGCTAT-3′ | |

| Cxcl7 (Ppbp) | F: 5′-TCGTCCTGCACCAGGGCCTG-3′ |

| R: 5′-AAGGGGAGCCAGCGCAACAA-3′ | |

| Hprt | F: 5′-CCTAAGATGAGCGCAAGTTGAA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CCACAGGACTAGAACACCTGCTAA-3′ | |

| Il17 | F: 5′-TTTAACTCCCTTGGCGCAAAA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CTTTCCCTCCGCATTGACAC-3′ | |

| Il17Ra | F: 5′-CATCAGCGAGCTAATGTCACA-3′ |

| R: 5′-AGCGTGTCTCAAACAGTCATTTA-3′ | |

| IL23 | F: 5′-TGCAAAGGATCCACCAGGGTCTGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-TAGGTGCCATCCTTGAGCTGCTGC-3′ | |

| IL6 | F: 5′-CCAGCTATGAACTCCTTCTC-3′ |

| R: 5′-GCTTGTTCCTCACATCTCTC-3′ | |

| CSF3 | F: 5′-AGACAGGGAAGAGCAGAACGG-3′ |

| R: 5′-GCCAGAGTGAGGGGTGCAA-3′ | |

| ACTB | F: 5′-TGAAGTGTGACGTGGACATC-3′ |

| R: 5′-ACTCGTCATACTCCTGCTTG-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

It was further normalized with parent Cl66 [2(−ΔΔCt)]. Melting curve analysis was performed to check the specificity of the amplified product. The details of gene-specific primers are in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

Slides were deparaffinized and processed for antigen retrieval using citrate buffer (10 mmol/L, pH = 6) or Tris-EDTA buffer (pH = 9) in a pressure cooker. Endogenous peroxidase activity and non-specific binding were blocked, and slides were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day after washing, the slides were incubated with the secondary antibody. Immunoreactivity was determined using ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides without primary antibody served as a negative control. Images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E800 Microscope (Nikon, Houston, TX) equipped with Nikon digital sight DS-5M Camera and NIS-Elements BR software version 4.13.04 (Nikon). Cell number was quantitated by counting at least five different random fields at high resolution (magnification, ×200). The composite score was calculated by multiplying the intensity score by the percentage of positive cells. The details of primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibodies Used in This Study

| Antibody type | Target | Source | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibody | |||

| CXCR2 | CXCR2 | A kind gift from Dr. Robert Strieter (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE) | 1:1000 |

| Anti-GRO α | CXCL1 | Abcam (Cambridge, MA) | 1:500 |

| CXCL3 | CXCL3 | Bioss (Woburn, MA) | 1:500 |

| CXCL5 (ENA78) | CXCL5 | Cloud-Clone Corp. (Houston, TX) | 1:100 |

| H168 | IL17R | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) | 1:100 |

| RORγ (H190) | Th17 cells | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1:200 |

| Antimyeloperoxidase | Neutrophil | Abcam | 1:100 |

| T-cell surface glycoprotein CD3 ε chain | CD3 | Dako (Santa Clara, CA) | 1:100 |

| Secondary antibody | |||

| Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody | Vector Laboratories (CA) | 1:500 | |

| Biotinylated donkey anti-goat IgG antibody | Jackson ImmunoResearch (PA) | 1:500 |

CXCR, CXC chemokine receptor; ENA, epithelial-derived neutrophil-activating peptide; GRO, growth-regulated oncogene; ROR, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma; Th17, type 17 helper.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Cell-free supernatants were collected after treatment of cells with different concentrations of recombinant murine IL-17 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 24 hours. CXCL1 (catalog number DY453), CXCL5 (catalog number DY452), and IL-17 (catalog number DY421) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used, according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, wells were coated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The next day, after blocking and washing, samples and standards were added in duplicate. After incubation with the secondary antibody, the reaction was developed and read using an ELx800 (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT) plate reader. Concentrations of CXCL1 and CXCL5 were normalized using the absorbance reading from the cell viability assay.

Cell Viability Assay

MDA-MB-231, Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells were plated in triplicate at a density of 5000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and incubated in a carbon dioxide incubator overnight. The following day, the cells were treated with different concentrations of IL-17 for 24 hours or IL-17 together with doxorubicin or paclitaxel for 72 hours. MTT (EMD Millipore Corp., Burlington, MA; 2 mg/mL) was added to each well, followed by incubation in a carbon dioxide incubator for 2 to 4 hours. The medium was aspirated, and 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well. The plates were read using an ELx800 plate reader.

Percentage viability was calculated as follows: 100*[(absorbance of the treatment − absorbance of the control group)/average of the control group].

Percentage inhibition was calculated as follows: 100*[(absorbance of the control group − absorbance of the treatment group)/average of the control group].

Tumor Growth and Metastasis

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Female BALB/c mice (aged 6 to 8 weeks) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD) and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions. Orthotropic injection of the cells (Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac; 50,000 in 50 μL of Hanks' balanced salt solution) in the mammary fat pad lead to the formation of tumors. Tumor growth was monitored, and animals were euthanized when they were moribund. Tumor volume was measured twice a week. Tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: tumor volume = π/6 × (smaller diameter)2 × (larger diameter).

Tumor tissues were harvested and processed for further analysis.

Isolation of Murine Neutrophils

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mL thioglycollate and euthanized 24 hours later. Peritoneal exudate cells were isolated after injection of 5 mL Hanks' balanced salt solution into the cavity by syringe. The harvested cells were washed and counted. More than 90% of cells were polymorphonuclear cells, as determined by cytochemistry.32

Chemotactic Assay

Costar Transwell cell culture inserts (12-mm diameter; pore size, 3 μm; Corning, Tewkbury, MA) were used to study the migration of murine neutrophils and differentiated MPRO Clone 2.1 cells. Murine neutrophils (2 × 107 cells/mL) and MPRO Clone 2.1 cells (2 × 107 cells/mL) with or without treatment of 3 nmol/L CXCR2 antagonist SCH 527123 (kindly provided by the Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, NJ) for 4 hours were added to the top of the transwell. Treatments (Cl66 serum-free supernatant, Cl66-Dox serum-free supernatant, Cl66-Pac serum-free supernatant, Cl66 serum-free supernatant after treatment with 10 ng/mL IL-17 for 24 hours, Cl66-Dox serum-free supernatant after treatment with 10 ng/mL IL-17 for 24 hours, and 10 ng/mL Cl66-Pac serum-free supernatant after treatment with IL-17 for 24 hours) and controls (serum-free media as a negative control and 10% serum containing media as a positive control) were added to the carrier plates. After incubating for 1 to 4 hours at 37°C, cells on the top of the transwell were removed, fixed, and stained using Hema-3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The number of neutrophils was quantitated using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a Nikon digital sight DS-5M camera at a magnification of ×200 using ImageJ software version 1.51j8 (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Coculture Assay

Corning Costar Transwell cell culture inserts (0.4-μm polycarbonate membrane) were used for coculturing HL60 cells with Cl66, Cl66-Dox, or Cl66-Pac cells. Serum-free medium containing HL60 cells (3 × 107 cells in total) was added to the top of the transwells; and the Cl66, Cl66-Dox, or Cl66-Pac cells were added to the carrier plates. After incubation for 24 hours, the HL60 cells on the top of transwell were collected for further experiments.

Western Blot Analysis

Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells are plated in the cell density of 3 × 105 per well in a 100-mm dish for overnight, then incubated for 24 hours in serum-free media. Western blot analysis was performed, as described previously.33 We detected the protein levels of IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) in Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells by using IL-17R (H-168) sc-30175 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Actin (A2066; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as control.

Statistical Analysis

In vitro and in vivo data were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks with Tukey test for multiple comparisons and U-test or two-sample t-test for comparison between two independent groups. The results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software version 6.02 or 8.1.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and are presented as means ± SEM. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac Cell Lines Express IL-17 and IL-17R, and Resistant Cells Secrete Higher Levels of CXCR2 Ligands

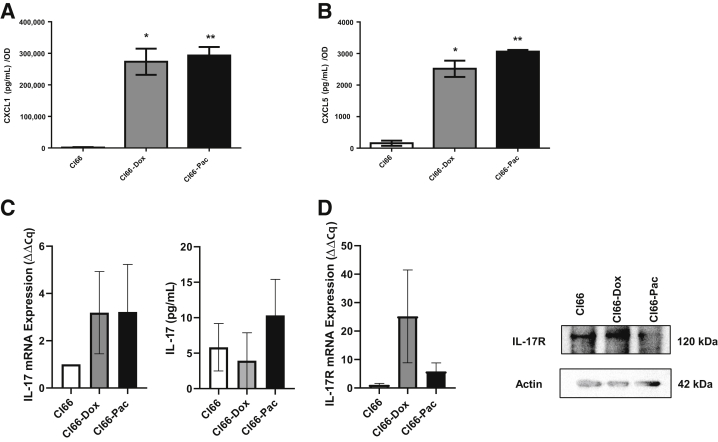

To assess the relationship between the IL-17/CXCR2 axis and chemotherapy resistance, the murine breast cancer cell line Cl66, cells resistant to doxorubicin (Cl66-Dox), or cells resistant to paclitaxel (Cl66-Pac) were used. The resistant cancer cells express more CXCR2 ligands than their parent cell.9 Significantly higher levels of CXCL1 (Figure 1A) and CXCL5 (Figure 1B) were observed in Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells compared with parental controls. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to quantify the expression of IL17 (Figure 1C) and IL17R (Figure 1D) in these cells. Both chemotherapy-resistant cell lines and parent cells showed expression of IL17 and IL17R at the mRNA level. To confirm these findings at the protein level, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed to detect IL-17 secreted by Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells (Figure 1C) and immunoblotting was performed for IL-17R levels in parent and resistant cells by Western blot analysis (Figure 1D). Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells showed positive protein expression of IL-17 and IL-17R. These results suggest that cancer cells express IL-17R and might respond to IL-17 stimulation.

Figure 1.

Expression levels of IL17 and IL17R in the parent, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cell lines. A and B: Levels of CXCL1 (A) and CXCL5 (B) in the supernatant of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). C: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of IL17 and level of IL-17 in the supernatant of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac, as determined by ELISA. D: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of IL17R and level of IL-17R in the Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac, and its confirmation by Western blot analysis. The values are fold change (unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). The data are representative of three quantitative RT-PCR experiments performed in duplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A–D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus Cl66.

Drug-Resistant Tumors Express Higher Levels of IL-17–CXCR2 Axis Players

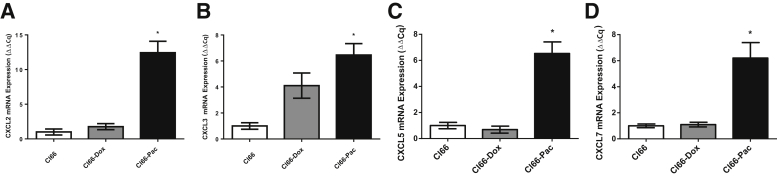

To define the association between the IL-17–CXCR2 axis and chemotherapy resistance, the mRNA levels of CXCR2, CXCR2 ligands, IL17, and IL17R were evaluated in the tumors formed by parent Cl66 and drug-resistant (Cl66-Dox or Cl66-Pac) cells. Cl66-Pac tumor lysates exhibited significantly higher mRNA levels of CXCL2 (Figure 2A), CXCL3 (Figure 2B), CXCL5 (Figure 2C), and CXCL7 (Figure 2D) in comparison with tumors formed by the parent Cl66 cell line (Figure 2). Insignificant higher levels of CXCL1 (Supplemental Figure S1A) and CXCR2 (Supplemental Figure S1B) were also observed in Cl66-Pac tumors in comparison with the parent Cl66 cells. Also, all of the tumors (Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac) expressed the IL17 and IL17R (Supplemental Figure S1, C and D). Cl66-Pac tumors expressed the highest mRNA levels of IL17 and IL17R compared with Cl66 and Cl66-Dox tumors (differences are not significant). Together, higher expression levels of CXCR2 ligands, CXCR2, IL17, and IL17R, were observed in tumor-bearing mice injected with Cl66-Pac cells in comparison with the parent Cl66 tumors.

Figure 2.

Chemotherapy-resistant tumors express higher mRNA levels of CXCR2 ligands. Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of CXCR2 ligands CXCL2 (A), CXCL3 (B), CXCL5 (C), and CXCL7 (D) in primary tumors generated from Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. The values are fold change (Cq; unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A–D). n = 5 per group (A–D). *P < 0.05 versus Cl66.

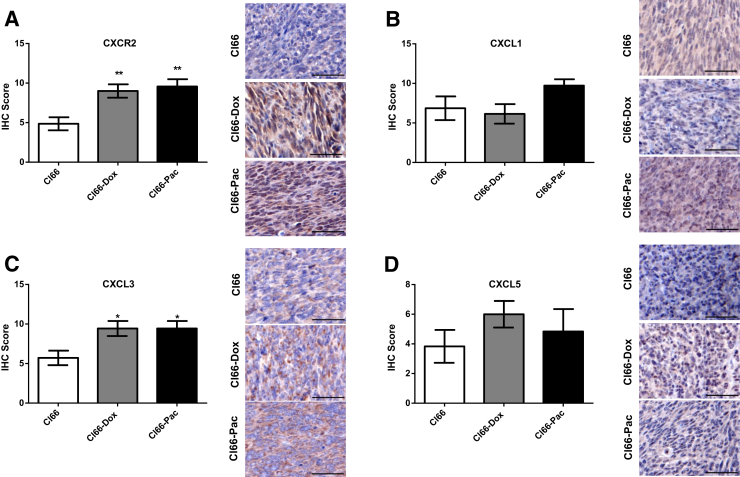

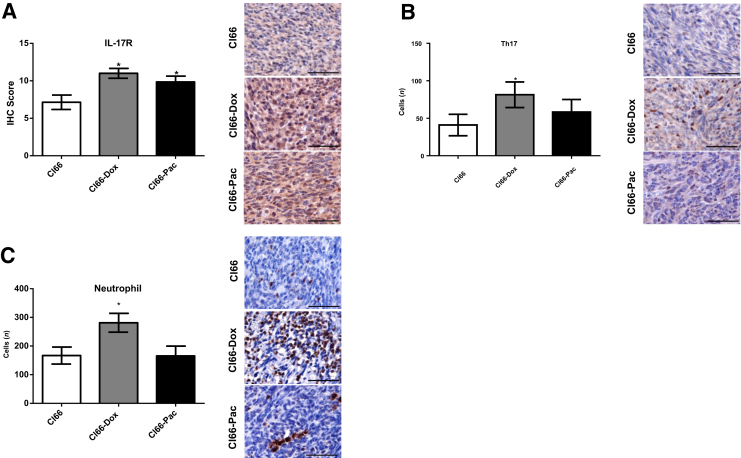

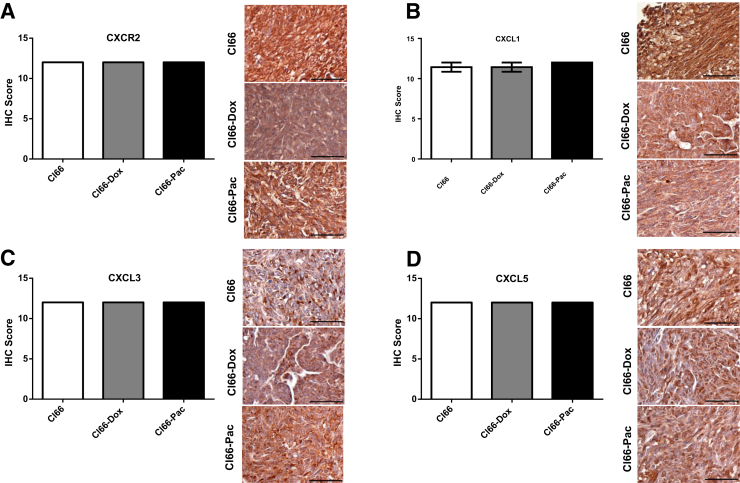

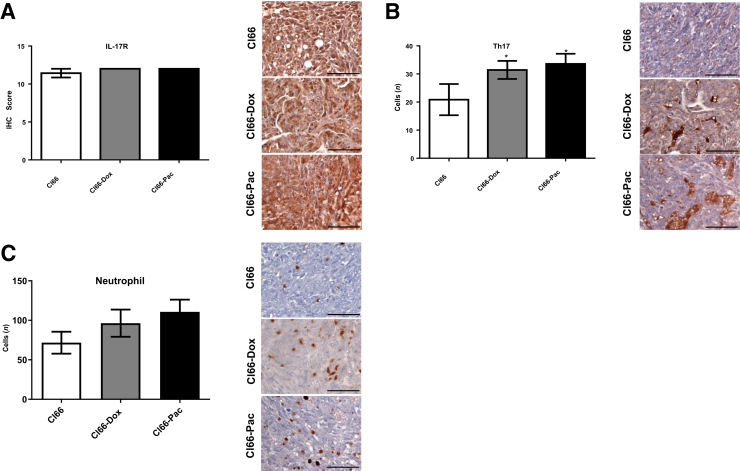

To further confirm these observations at the protein level, the levels of CXCR2 (Figure 3A), CXCR2 ligands (Figure 3, B–D), and IL-17R (Figure 4A) were analyzed using immunohistochemistry. A significant increase was observed in CXCR2 (Figure 3A) and CXCL3 (Figure 3C) in Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac primary tumor sites compared with Cl66 primary tumor sites (Figure 3, A and C). A nonsignificant increase for CXCL1 (Figure 3B) was also observed in Cl66-Pac tumors, and a nonsignificant increase in CXCL5 (Figure 3D) was observed in Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac tumors. Furthermore, a significant increase was observed in IL-7R expression in the Cl66 resistant tumors in comparison with the parent Cl66 (Figure 4A). There are some differences between mRNA and protein levels of CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands. However, the overall trend is similar: the resistant cells express higher levels of CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands. However, similar to previous reports, differences were observed in the levels of mRNA and protein expression levels.34

Figure 3.

High expression of CXCR2 and CXCR ligands in the primary tumors of resistant cells. Representative images and bar graphs showing immunohistochemical (IHC) score of CXCR2 (A), CXCL1 (B), CXCL3 (C), and CXCL5 (D) in the primary tumors of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 per group (A–D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus Cl66. Scale bars = 50 μm (A–D).

Figure 4.

Increased type 17 helper (Th17) cell and neutrophil infiltration with higher expression of IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) in the primary tumors of resistant cells. Representative images and bar graphs showing immunohistochemical score of IL-17R (A), Th17 (B), and neutrophil infiltration (C), in the primary tumors of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 per group (A–C). *P < 0.05 versus Cl66. Scale bars = 50 μm (A–C).

Drug-Resistant Tumors Show Increased Infiltration of Th17 Cells and Neutrophils

A significant increase in the number of Th17 cells in the Cl66-Dox tumors was observed (Figure 4B). A nonsignificant increase of Th17 cells was also observed in the Cl66-Pac tumor. The results show increased recruitment of Th17 cells, the major contributor of IL-17,18 in resistant tumors, indicating higher levels of IL-17 in resistant tumors. The number of neutrophils in Cl66 parent and resistant tumors was examined. Significantly increased numbers of neutrophils were observed in Cl66-Dox tumor in comparison with Cl66 parent tumor (Figure 4C). In addition, the expression of CXCL3 was significantly correlated with neutrophil numbers on the primary tumor sites (r2 = 0.44; P = 0.001; data not shown). Together, these results suggest an association between increased IL-17–CXCR2 levels with higher neutrophil recruitment.

Higher Levels of CXCR2, CXCR2 Ligands, and IL-17R on Metastatic Tumor Sites

Both IL-17 and CXCR2 ligands have been demonstrated to promote tumor metastasis and to play vital roles within the tumor microenvironment through recruiting tumor-promoting neutrophils to the tumor site.35, 36, 37, 38 It was investigated whether there is a difference in the levels of CXCR2, CXCR2 ligands, and IL-17R between metastatic tumors and primary tumors. An overall increase in CXCR2 (Figure 5A), CXCR2 ligands (Figure 5, B–D), and IL-17R (Figure 6A) levels was observed on the metastatic sites in comparison with the expression of CXCR2 (Figure 3A), CXCR2 ligands (Figure 3, B–D), and IL-17R (Figure 4A) in primary tumors. All the metastatic tumors expressed extremely high levels of CXCR2, CXCR2 ligands, and IL-17R in comparison with primary tumor sites, showing a different expression pattern between resistant tumors and primary tumors. A significantly higher number of Th17 cells (Figure 6B) and a nonsignificant increase of neutrophils numbers (Figure 6C) in the metastatic lesions of resistant tumors in comparison with the metastatic lesions of parent cells were also observed.

Figure 5.

High CXCR2/CXCR2 ligand levels in the metastatic tumor sites. Representative images and bar graphs showing immunohistochemical (IHC) score of CXCR2 (A), CXCL1 (B), CXCL3 (C), and CXCL5 (D) in the metastatic lesions of the lung in the mice injected with Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 per group (A–D). Scale bars = 50 μm (A–D).

Figure 6.

Increased type 17 helper (Th17) cell and neutrophil infiltration in the metastatic tumor sites. Representative images and bar graphs showing immunohistochemical (IHC) score of IL-17 receptor (A), Th17 (B), and neutrophil infiltration (C) in the metastatic lesions of the lung in the mice injected with Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 per group (A–C). *P < 0.05 versus Cl66. Scale bars = 50 μm (A–C).

The numbers of CD3+ T cells were studied in the primary and metastatic tumors of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac (Supplemental Figure S2). A significant decrease of CD3+ T cell numbers was observed in Cl66-Pac primary tumors (Supplemental Figure S2A), and no significant difference of CD3+ T cell numbers was observed in the metastatic tumor sites of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac (Supplemental Figure S2B). Higher neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio was observed in the primary sites of resistant cells, which indicated higher immunosuppression on the Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac primary tumor sites (Supplemental Figure S2C). However, the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio on the metastatic tumor sites was not different between Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac (Supplemental Figure S2D).

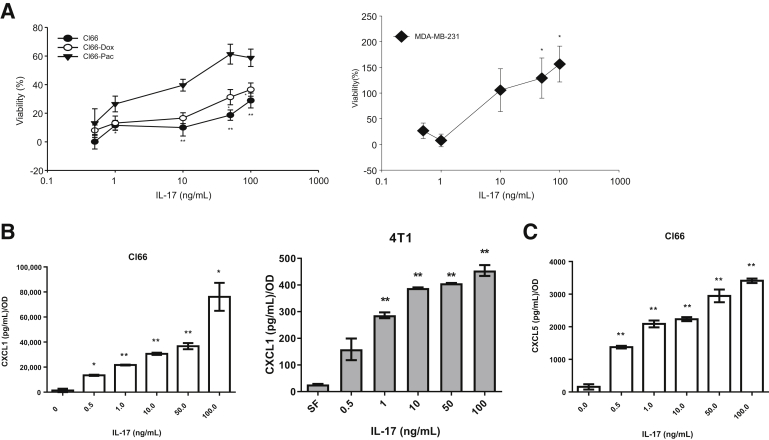

IL-17A Enhances Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Secretion of CXCR2 Ligands

IL-17 has been reported to promote breast cancer progression.12,39 However, the detailed mechanism remains unknown. To understand the effect of IL-17 on tumor cells, parental Cl66, resistant Cl66 cells, and MDA-MB-231 were treated with IL-17. The treatment with IL-17 promoted the proliferation of parental Cl66 and resistant Cl66 cells, and MDA-MB-231, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7A). Moreover, IL-17 treatment of Cl66 and 4T1 cells enhanced the production of CXCR2 ligands, CXCL1 (Figure 7B), and CXCL5 (Figure 7C), in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7, B and C). However, treatment of IL-17 did not facilitate Cl66 resistance to chemotherapy drugs, paclitaxel, or doxorubicin (Supplemental Figure S3). These results suggest that IL-17 promotes cancer progression by facilitating the up-regulation of CXCR2 ligands, which positively promotes the mobilization of procancer neutrophils to the tumor site.

Figure 7.

IL-17 treatment enhances proliferation and the secretion of CXCR2 ligands in tumor cells. A: Relative viability of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, Cl66-Pac, and MDA-MB-231 cells in response to IL-17 treatment compared with serum-free media. The MTT assay determined cell viability. B: Levels of CXCL1 in the supernatant of Cl66 cells and 4T1 cells, as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), in response to IL-17 treatment compared with serum-free (SF) media. C: Levels of CXCL5 in the supernatant of Cl66 cells, as determined by ELISA, in response to IL-17 treatment compared with serum-free media. The data are representatives of three experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (unpaired t-test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus no treatment.

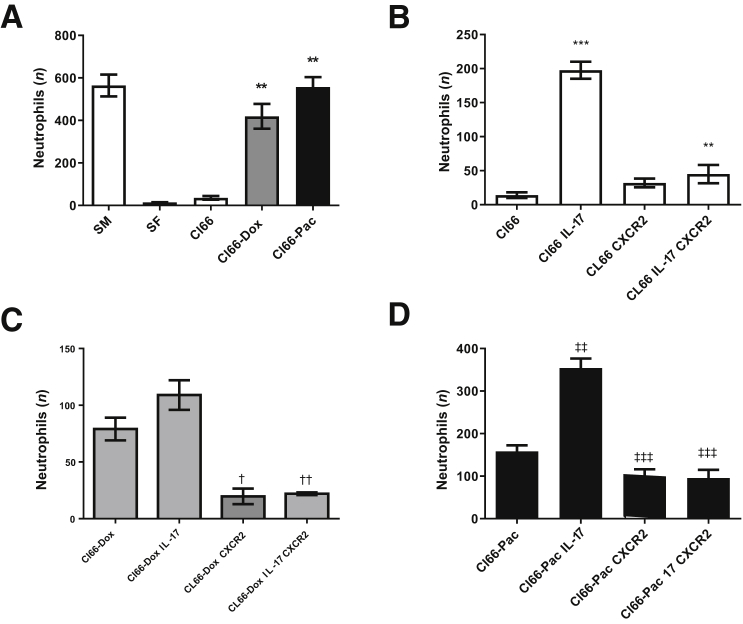

Chemotherapy-Resistant Tumor Cells Positively Regulate Neutrophil Chemotaxis

On the basis of our previous studies, the chemotherapy-resistant cells (Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac) produced higher levels of CXCR2 ligands,9 which are crucial for promoting the neutrophil recruitment to the tumor site. It was examined whether chemotherapy-resistant cells can recruit more neutrophils. The cell-free supernatant was collected from Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac; and murine peritoneal neutrophils were isolated, and a chemotactic assay was performed. The supernatant of Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac cells recruited significantly higher numbers of murine neutrophils in comparison with parent cells (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

IL-17 treatment enhances neutrophil chemotaxis dependent on CXCR2 signaling. A: Chemotaxis of murine neutrophils in response to the supernatant of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac compared with serum-free (SF) media. U-test was used. Serum containing media (SM) is used as positive control. B: Chemotaxis of differentiated MPRO cells (treated with or without CXCR2 antagonist) in the response of supernatant of Cl66 and Cl66 treated with IL-17. C: Chemotaxis of differentiated MPRO cells (treated with or without CXCR2 antagonist) in response of supernatant of Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Dox treated with IL-17. D: Chemotaxis of differentiated MPRO cells (treated with or without CXCR2 antagonist) in response of supernatant of Cl66-Pac and Cl66-Pac treated with IL-17. Unpaired t-test was used. The data are representatives of three experiments performed in duplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A–D). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus Cl66; †P < 0.05 and ††P < 0.01 versus Cl66-Dox; ‡P < 0.01 and ‡‡‡P < 0.001 versus Cl66-Pac.

Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac cells were further treated with 10 ng/mL recombinant IL-17 for 24 hours, then the supernatant was collected and another chemotactic assay was performed with differentiated MPRO Clone 2.1 cells (neutrophils). The MPRO Clone 2.1 cells were with or without treatment of CXCR2 antagonist, SCH 527123, for 4 hours. The resistant cells recruited higher numbers of neutrophils in comparison with the parent cells (Figure 8, B–D). Overall, the IL-17–treated tumor cells recruited higher numbers of neutrophils; and targeting CXCR2 in these cells significantly inhibited the chemotaxis (Figure 8, B–D). These results suggest that IL-17 promotes chemotaxis of neutrophils through secretion of CXCR2 ligands, and blocking of CXCR2 signaling in the neutrophils can inhibit this IL-17–dependent neutrophil recruitment.

The interactions between neutrophils and cancer cells were also examined. The differentiated HL60 cells were cocultured with Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and or Cl66-Pac cells. When cocultured with cancer cells, HL60 cells expressed Th17 priming factor, IL23, as well as the proinflammatory cytokine, IL6 (Supplemental Figure S4, A and B),40,41 and G-CSF (Supplemental Figure S4C). G-CSF is the crucial regulator for neutrophil mobilization from bone marrow to the blood.13 However, the protein levels of these factors were below the detection levels of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits used (catalog numbers DY206-05, DY1290-05, and DY214-05; R&D Systems; data not shown).

Discussion

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancer types that afflicts women, and there is an urgent need to understand cancer progression further, to improve treatments and discover biomarkers for breast cancer patients.42 In this study, we report that an IL-17/CXCR2 ligand axis facilitates breast cancer therapy resistance and metastasis by recruiting neutrophils to the tumor microenvironment. The results demonstrate that IL-17 increases in the tumor microenvironment, particularly in therapy-resistant tumor microenvironments. IL-17, thus, up-regulates the expression of CXCR2 ligands, promoting the recruitment of cancer-promoting neutrophils. These findings also explain why higher levels of CXCR2 ligands and IL-17 are associated with lower survival rates in cancer patients23,43,44 and suggest why patients who develop resistance to chemotherapy have lower survival rates. The data also suggest that resistant cells secrete higher levels of protumor factors, including CXCR2 ligands, to recruit increased numbers of neutrophils to the tumor site, which promotes cancer-associated inflammation. Increased Th17 cell recruitment was also observed in resistant tumors, which indicates that resistant tumors might be more dependent on the IL-17–CXCR2 axis compared with nonresistant tumors.

Resistant tumors exhibit a more malignant phenotype, including highly metastatic behavior and angiogenesis.9 In this study, overall increased levels of protumor factors (CXCR2, CXCR2 ligands, IL-17R, neutrophils, and Th17 cells) were observed in Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac primary tumors. Expression of CXCL3 significantly correlated with neutrophil numbers on the primary tumor sites (r2 = 0.44; P = 0.001). However, the expression patterns of CXCR2 ligands in Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac tumors still differed, perhaps because the differential regulation of CXCR2 ligands also depends on chemotherapy used.9 Because Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac received different chemotherapy drug treatments, the phenotype and expression patterns of Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac become different.

The major contributor of IL-17 is the Th17 cell,14 so more Th17 cells were expected to be recruited to the resistant tumor sites. Higher numbers of neutrophils were also observed recruited to the resistant tumor sites, which corresponds to the higher recruitment of Th17 cells. This result also indicates the interactions between immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Malignant tumors, in general, express higher levels of CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands compared with nonmalignant tumors or healthy tissues.9 The increased secretion of CXCR2 ligands in metastatic lesions highlights the differences between metastatic and primary tumor sites. CXCR2 ligands can facilitate resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs22; however, IL-17 did not facilitate tumor cell resistance to chemotherapy. These results indicate that IL-17 promotes cancer progression mostly through up-regulation of CXCR2 ligands and promotion of neutrophil chemotaxis. This observation indicates the importance of the tumor microenvironment in the ability of tumor cells to develop therapy resistance.

Cancer progression and therapy resistance are due to the interactions between cancer cells and infiltrating immune cells, other than only cancer cells or single procancer factors.45 For example, in this study, compared with parental cells, the therapy-resistant cells were capable of recruiting higher numbers of neutrophils, which are a significant component of the myeloid cell population.13 The higher numbers of neutrophils suggest an association with the higher levels of protumor factors released by neutrophils in the therapy-resistant tumor microenvironment of breast cancer. Coculturing HL60 cells with therapy-resistant cells led to a higher level of IL23 compared with the HL60 cells cultured with parent cells, which are the crucial regulator for Th17 cells.46

A recent report showed that myeloid cell–produced IL-23 facilitates prostate cancer cell resistance to therapy.47 Similarly, the therapy-resistant cells were capable of recruiting higher numbers of neutrophils, which are a significant component of the myeloid cell population.48 The higher numbers of neutrophils suggest an association with the higher levels of IL-23 seen in the therapy-resistant tumor microenvironment of breast cancer.

As the most abundant leukocytes in the innate immune system, neutrophils promote cancer progression through multiple mechanisms, including facilitating cancer therapy resistance and metastasis.49 For instance, it has been shown that neutrophils can mobilize to premetastatic sites and establish a premetastatic niche for the tumor cells.50 Neutrophils are also found to release proteases, including neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and metalloprotease 9, from their primary granules; and those proteases also play a role in cancer progression by facilitating chemotherapy resistance, angiogenesis, and metastasis.13 Moreover, neutrophils themselves can secrete factors, like transforming growth factor-β, facilitating immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Transforming growth factor-β recently has also been suggested to play a part in Th17 priming.51 Together, our data suggest a feed-forward loop of neutrophil-promoted cancer progression, and higher levels of infiltrated neutrophils decrease the survival rates of the cancer patients.26 However, the detailed mechanisms regarding neutrophil-promoted cancer progression are still in need of further investigation.

Overall, these results indicate CXCR2 ligands, together with neutrophils, should be considered as potential targets and biomarkers for breast cancer treatment; targeting neutrophils and CXCR2 ligands may be able to reduce breast cancer chemotherapy resistance and metastasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yuri Sheinin, M.D., Ph.D., and Dr. Dipakkumar R. Prajapati, M.D., for helping with the pathologic evaluation.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute/NIH grantR01CA228524, and National Cancer Institute/NIH Cancer Center Support grant P30CA036727. L.W., as a graduate student, is supported by a scholarship from the Chinese Scholarship Council and a predoctoral fellowship from the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.09.016.

Supplemental Data

Chemotherapy-resistant tumors express higher mRNA levels of CXCL1, CXCR2, IL-17, and IL-17 receptor (IL-17R). A–D: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of CXCL1 (A), CXCR2 (B), IL17 (C), and IL17R (D) in primary tumors generated from Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. The values are fold change (Cq; unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 5 per group (A–D).

Higher neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is present in the primary tumors of resistant cells. A and B: Bar graphs and representative images showing CD3+ T cells in the primary tumors (A), and metastatic tumors (B) of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. C and D: NLR ratios in the primary (C) and metastatic (D) tumors of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 (A and B). *P < 0.05 versus Cl66. Scale bars = 50 μm (A and B).

IL-17 treatment does not facilitate Cl66 resistance to paclitaxel and doxorubicin. A and B: Relative percentage inhibition, as determined by MTT, of Cl66 treated with doxorubicin (A) and paclitaxel (B) with or without IL-17 treatment compared with the serum-free media. The data are representatives of three experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

HL60 cells cocultured with Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac elevate the expression levels of IL-17 priming factors, and supernatant of resistant cells enhances neutrophil chemotaxis. A–C: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of IL23 (A), IL6 (B), and G-CSF (C) in HL60 cells cocultured with chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells and parent cells. Values are fold change (Cq; unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). The data are representatives of three quantitative RT-PCR experiments performed in duplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01 versus HL60 + Cl66.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K.D., Siegel R.L., Lin C.C., Mariotto A.B., Kramer J.L., Rowland J.H., Stein K.D., Alteri R., Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez E.A. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced breast cancer: efficacy and cardiac considerations. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:155–164. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tampaki E.C., Tampakis A., Alifieris C.E., Krikelis D., Pazaiti A., Kontos M., Trafalis D.T. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant treatment with bevacizumab, liposomal doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel combination in locally/regionally advanced, HER2-negative, grade III at premenopausal status breast cancer: a phase II study. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:639–648. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad A. Pathways to breast cancer recurrence. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:290568. doi: 10.1155/2013/290568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karagiannis G.S., Pastoriza J.M., Wang Y., Harney A.S., Entenberg D., Pignatelli J., Sharma V.P., Xue E.A., Cheng E., D'Alfonso T.M., Jones J.G., Anampa J., Rohan T.E., Sparano J.A., Condeelis J.S., Oktay M.H. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces breast cancer metastasis through a TMEM-mediated mechanism. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan0026. eaan0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samanta D., Park Y., Ni X., Li H., Zahnow C.A., Gabrielson E., Pan F., Semenza G.L. Chemotherapy induces enrichment of CD47(+)/CD73(+)/PDL1(+) immune evasive triple-negative breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E1239–E1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718197115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yano S., Takehara K., Kishimoto H., Tazawa H., Urata Y., Kagawa S., Bouvet M., Fujiwara T., Hoffman R.M. High-metastatic triple-negative breast-cancer variants selected in vivo become chemoresistant in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2017;53:285–287. doi: 10.1007/s11626-016-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma B., Varney M.L., Saxena S., Wu L., Singh R.K. Induction of CXCR2 ligands, stem cell-like phenotype, and metastasis in chemotherapy-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;372:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wirtz D., Konstantopoulos K., Searson P.C. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:512–522. doi: 10.1038/nrc3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patil R.S., Shah S.U., Shrikhande S.V., Goel M., Dikshit R.P., Chiplunkar S.V. IL17 producing gammadeltaT cells induce angiogenesis and are associated with poor survival in gallbladder cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:869–881. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffelt S.B., Wellenstein M.D., de Visser K.E. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin W., Dong C. IL-17 cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e60. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurtado C.G., Wan F., Housseau F., Sears C.L. Roles for interleukin 17 and adaptive immunity in pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1706–1715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das Roy L., Pathangey L.B., Tinder T.L., Schettini J.L., Gruber H.E., Mukherjee P. Breast-cancer-associated metastasis is significantly increased in a model of autoimmune arthritis. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kersten K., Coffelt S.B., Hoogstraat M., Verstegen N.J.M., Vrijland K., Ciampricotti M., Doornebal C.W., Hau C.S., Wellenstein M.D., Salvagno C., Doshi P., Lips E.H., Wessels L.F.A., de Visser K.E. Mammary tumor-derived CCL2 enhances pro-metastatic systemic inflammation through upregulation of IL1beta in tumor-associated macrophages. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1334744. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1334744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabre J., Giustiniani J., Garbar C., Antonicelli F., Merrouche Y., Bensussan A., Bagot M., Al-Dacak R. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: the protumor effects of IL-17 related to cancer type. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17091433. E1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochaud S., Giustiniani J., Thomas C., Laprevotte E., Garbar C., Savoye A.M., Cure H., Mascaux C., Alberici G., Bonnefoy N., Eliaou J.F., Bensussan A., Bastid J. IL-17A is produced by breast cancer TILs and promotes chemoresistance and proliferation through ERK1/2. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3456. doi: 10.1038/srep03456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen J., Sun X., Pan B., Cao S., Cao J., Che D., Liu F., Zhang S., Yu Y. IL-17 induces macrophages to M2-like phenotype via NF-kappaB. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4217–4228. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S174899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Numasaki M., Watanabe M., Suzuki T., Takahashi H., Nakamura A., McAllister F., Hishinuma T., Goto J., Lotze M.T., Kolls J.K., Sasaki H. IL-17 enhances the net angiogenic activity and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice through promoting CXCR-2-dependent angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175:6177–6189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma B., Nawandar D.M., Nannuru K.C., Varney M.L., Singh R.K. Targeting CXCR2 enhances chemotherapeutic response, inhibits mammary tumor growth, angiogenesis, and lung metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:799–808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li A., King J., Moro A., Sugi M.D., Dawson D.W., Kaplan J., Li G., Lu X., Strieter R.M., Burdick M., Go V.L., Reber H.A., Eibl G., Hines O.J. Overexpression of CXCL5 is associated with poor survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele C.W., Karim S.A., Leach J.D.G., Bailey P., Upstill-Goddard R., Rishi L., Foth M., Bryson S., McDaid K., Wilson Z., Eberlein C., Candido J.B., Clarke M., Nixon C., Connelly J., Jamieson N., Carter C.R., Balkwill F., Chang D.K., Evans T.R.J., Strathdee D., Biankin A.V., Nibbs R.J.B., Barry S.T., Sansom O.J., Morton J.P. CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:832–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffelt S.B., Kersten K., Doornebal C.W., Weiden J., Vrijland K., Hau C.S., Verstegen N.J.M., Ciampricotti M., Hawinkels L., Jonkers J., de Visser K.E. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentles A.J., Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Bratman S.V., Feng W., Kim D., Nair V.S., Xu Y., Khuong A., Hoang C.D., Diehn M., West R.B., Plevritis S.K., Alizadeh A.A. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aslakson C.J., Miller F.R. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulaski B.A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;39:20.2.1–20.2.16. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im2002s39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millius A., Weiner O.D. Manipulation of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells for the study of directed cell migration. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;591:147–158. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-404-3_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta D., Shah H.P., Malu K., Berliner N., Gaines P. Differentiation and characterization of myeloid cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2014;104:22F.5.1–22F.5.28. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22f05s104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxena S., Purohit A., Varney M.L., Hayashi Y., Singh R.K. Semaphorin-5A maintains epithelial phenotype of malignant pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1283. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pillay J., Tak T., Kamp V.M., Koenderman L. Immune suppression by neutrophils and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells: similarities and differences. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3813–3827. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadanandam A., Rosenbaugh E.G., Singh S., Varney M., Singh R.K. Semaphorin 5A promotes angiogenesis by increasing endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and decreasing apoptosis. Microvasc Res. 2010;79:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Y., Xiao P., Lei S., Deng F., Xiao G.G., Liu Y., Chen X., Li L., Wu S., Chen Y., Jiang H., Tan L., Xie J., Zhu X., Liang S., Deng H. How is mRNA expression predictive for protein expression? a correlation study on human circulating monocytes. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:426–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li T.J., Jiang Y.M., Hu Y.F., Huang L., Yu J., Zhao L.Y., Deng H.J., Mou T.Y., Liu H., Yang Y., Zhang Q., Li G.X. Interleukin-17-producing neutrophils link inflammatory stimuli to disease progression by promoting angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1575–1585. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A., Cherukumilli M., Mahmoudpour S.H., Brand K., Bandapalli O.R. ShRNA-mediated knock-down of CXCL8 inhibits tumor growth in colorectal liver metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;500:731–737. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong L., Cumpian A.M., Caetano M.S., Ochoa C.E., De la Garza M.M., Lapid D.J., Mirabolfathinejad S.G., Dickey B.F., Zhou Q., Moghaddam S.J. Promoting effect of neutrophils on lung tumorigenesis is mediated by CXCR2 and neutrophil elastase. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:154. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamieson T., Clarke M., Steele C.W., Samuel M.S., Neumann J., Jung A., Huels D., Olson M.F., Das S., Nibbs R.J., Sansom O.J. Inhibition of CXCR2 profoundly suppresses inflammation-driven and spontaneous tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3127–3144. doi: 10.1172/JCI61067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akbay E.A., Koyama S., Liu Y., Dries R., Bufe L.E., Silkes M., Alam M.M., Magee D.M., Jones R., Jinushi M., Kulkarni M., Carretero J., Wang X., Warner-Hatten T., Cavanaugh J.D., Osa A., Kumanogoh A., Freeman G.J., Awad M.M., Christiani D.C., Bueno R., Hammerman P.S., Dranoff G., Wong K.K. Interleukin-17A promotes lung tumor progression through neutrophil attraction to tumor sites and mediating resistance to PD-1 blockade. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1268–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revu S., Wu J., Henkel M., Rittenhouse N., Menk A., Delgoffe G.M., Poholek A.C., McGeachy M.J. IL-23 and IL-1beta drive human Th17 cell differentiation and metabolic reprogramming in absence of CD28 costimulation. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2642–2653. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heink S., Yogev N., Garbers C., Herwerth M., Aly L., Gasperi C., Husterer V., Croxford A.L., Moller-Hackbarth K., Bartsch H.S., Sotlar K., Krebs S., Regen T., Blum H., Hemmer B., Misgeld T., Wunderlich T.F., Hidalgo J., Oukka M., Rose-John S., Schmidt-Supprian M., Waisman A., Korn T. Trans-presentation of IL-6 by dendritic cells is required for the priming of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:74–85. doi: 10.1038/ni.3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Y., Luo B., An Y., Sun H., Cai H., Sun D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prognostic value of CXCR2 in solid tumor patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:109740–109751. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J., Wang L., Wang T., Wang J. Expression of IL-23R and IL-17 and the pathology and prognosis of urinary bladder carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:4325–4330. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coffelt S.B., de Visser K.E. Immune-mediated mechanisms influencing the efficacy of anticancer therapies. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:198–216. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwakura Y., Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1218–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calcinotto A., Spataro C., Zagato E., Di Mitri D., Gil V., Crespo M., De Bernardis G., Losa M., Mirenda M., Pasquini E., Rinaldi A., Sumanasuriya S., Lambros M.B., Neeb A., Luciano R., Bravi C.A., Nava-Rodrigues D., Dolling D., Prayer-Galetti T., Ferreira A., Briganti A., Esposito A., Barry S., Yuan W., Sharp A., de Bono J., Alimonti A. IL-23 secreted by myeloid cells drives castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2018;559:363–369. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0266-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engblom C., Pfirschke C., Pittet M.J. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu L., Saxena S., Awaji M., Singh R.K. Tumor-associated neutrophils in cancer: going pro. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:564. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wculek S.K., Malanchi I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;528:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature16140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin H., Wang L., Feng T., Elson C.O., Niyongere S.A., Lee S.J., Reynolds S.L., Weaver C.T., Roarty K., Serra R., Benveniste E.N., Cong Y. TGF-beta promotes Th17 cell development through inhibition of SOCS3. J Immunol. 2009;183:97–105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chemotherapy-resistant tumors express higher mRNA levels of CXCL1, CXCR2, IL-17, and IL-17 receptor (IL-17R). A–D: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of CXCL1 (A), CXCR2 (B), IL17 (C), and IL17R (D) in primary tumors generated from Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. The values are fold change (Cq; unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 5 per group (A–D).

Higher neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is present in the primary tumors of resistant cells. A and B: Bar graphs and representative images showing CD3+ T cells in the primary tumors (A), and metastatic tumors (B) of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. C and D: NLR ratios in the primary (C) and metastatic (D) tumors of Cl66, Cl66-Dox, and Cl66-Pac. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (U-test). n = 5 (A and B). *P < 0.05 versus Cl66. Scale bars = 50 μm (A and B).

IL-17 treatment does not facilitate Cl66 resistance to paclitaxel and doxorubicin. A and B: Relative percentage inhibition, as determined by MTT, of Cl66 treated with doxorubicin (A) and paclitaxel (B) with or without IL-17 treatment compared with the serum-free media. The data are representatives of three experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

HL60 cells cocultured with Cl66-Dox and Cl66-Pac elevate the expression levels of IL-17 priming factors, and supernatant of resistant cells enhances neutrophil chemotaxis. A–C: Quantitative RT-PCR for the expression of IL23 (A), IL6 (B), and G-CSF (C) in HL60 cells cocultured with chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells and parent cells. Values are fold change (Cq; unpaired t-test, assume both populations have the same SD). The data are representatives of three quantitative RT-PCR experiments performed in duplicate with similar results. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01 versus HL60 + Cl66.