Abstract

Questiomycin A (1) along with three new compounds, questiomycins C–E (2–4), were isolated from culture of Alteromonas sp. D, an algicidal marine bacterium, guided by algal lethality assay using the raphidophyte, Chattonella antiqua, one of the causative organisms of harmful algal bloom. The structures of 1–4 were assigned on the basis of their spectrometric and spectroscopic data. Compounds 1 to 4 exhibited algicidal activity against C. antiqua with LC50 values ranging from 0.18 to 6.37 μM. Co-cultivation experiment revealed that 1 was produced only when the microalgae and the bacterium are in close contact, suggesting that some interactions between them trigger the biosynthesis of questiomycins. These results suggested that the algicidal bacteria such as Alteromonas sp. D can control microalgae chemically in marine ecosystem.

Keywords: algicidal bacteria, questiomycins, phenoxazinone antibiotics, Alteromonas, Chattonella antiqua, harmful algal bloom, red tide

1. Introduction

Red tide, also known as harmful algal bloom (HAB), causes tremendous economic damage on the fisheries industries, and threatens coastal environment even human health [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Massive proliferation of certain algal species, such as the raphidophytes Chattonella antiqua, Heterosigma akashiwo, the dinoflagellates Karenia mikimotoi, Alexandrium tamarense, and the diatoms Eucampia zodiacus, Pseudo-nitzschia australis, are responsible for HAB [7]. Local eutrophication of coastal water, accompanied by economic development, is likely major factor to boost HABs, however recent climate change may enhances the risk of HAB globally [2,3]. To date, chemical and physical countermeasures such as cray dispersal and ultrasonic irradiation [8,9,10] have been used in attempts to control HAB. Although these methods are useful in certain areas [8], problems regarding effectiveness, cost, and secondary pollution are yet to be solved, and development of an alternative strategy is demanded.

Recently, marine bacteria that potently lyse microalgae, called algicidal bacteria, draw a great deal of attention as an environmentally friendly strategy to mitigate and prevent HAB [11]. Numbers of algicidal bacteria have been separated from various marine sources, and their taxonomy, distribution, and target microalgae are extensively studied [10,12,13,14]. Most of algicidal bacteria reported to date belong to phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, which are common taxa in the marine environment suggesting that algicidal bacteria are one of the key players in coastal ecosystems [12,13,14]. For example, algicidal bacteria are found in high density in the biofilm on seagrasses, suggesting that the algicidal bacteria inhabit the seagrass-borne biofilm, and are supplied to the coastal environment [6,15,16,17]. Algicidal bacteria attack algal cells in either direct (require attachment on the target algal cells) or indirect (release active molecules) manners [13,14]. The former uses some hydrolases, such as proteases and glycosidases, to lyse a variety of microalgal species [18,19,20,21]. Several low-molecular-weight compounds have also been identified as algicidal principals [12,13,22,23,24]. These molecules are released from the bacteria into the water, and these dispersed algicidal agents attack algal cells. Small molecular algicidal compounds tend to show some target specific activity. These findings encouraged the development of biological strategies to mitigate HABs, however the mechanisms and chemical basis of many algicidal bacteria are still left to be investigated. In the present study, we identified four aminophenoxazinone alkaloids, questiomycins A and C to E from Alteromonas sp. D, one of the first reported algicidal bacteria [11]. Here, isolation, structure elucidation, and algicidal activities of questiomycins are described. We also propose plausible chemo-ecological basis of algicidal actions of questiomycins triggered by close contact between the alga and bacterium.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Purificatin and Structure Elucidation

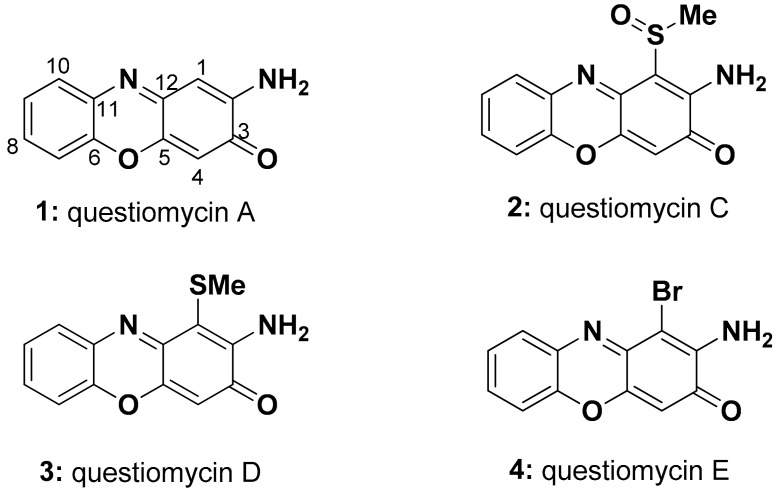

A total 1.6 L of Alteromonas sp. D culture was grossly separated by a reversed-phase C18 vacuum liquid chromatography. The active molecules eluting between 70% and 100% MeOH fractions were combined and further chromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column. The orange-colored band was collected and purified by reversed-phase HPLC to afford questiomycin A (2-aminophenoxazin-3-one, APO, (1, Figure 1)) as a major active compound [25]. Spectral data for 1 agreed well with those reported previously [26] (Table 1 and Table 2, Supplementary Materials Table S1). Three new compounds, questiomycins C–E (2–4, Figure 1), which exhibited nearly identical UV spectra and color with those of 1, were also purified as minor analogues from an additional large scale culture.

Figure 1.

Aminophenoxazinone-based algicidal molecules, questiomycin A (1) and new analogues C–E (2–4), from the marine bacterium Alteromonas sp. D.

Table 1.

1H NMR data for 1–4 (δH, mult. (J in Hz), DMSO-d6).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.36, s | |||

| 4 | 6.35, s | 6.46, s | 6.39, s | 6.40, s |

| 7 | 7.49, d (7.8) | 7.51, m | 7.51, m | 7.53, m |

| 8 | 7.46, t (7.9) | 7.51, m | 7.51, m | 7.53, m |

| 9 | 7.39, t (7.5) | 7.41, m | 7.43, m | 7.44, m |

| 10 | 7.70, d (7.9) | 7.70, d (7.8) | 7.82, d (7.9) | 7.80, d (7.9) |

| NH2 | 6.60, brs | 7.31, brs | 6.95, brs | 6.98, brs |

| 8.46, brs | ||||

| SOCH3 | 2.98, s | |||

| SCH3 | 2.31, s |

Table 2.

13C NMR data for 1–4 (δC, DMSO-d6).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 98.3 | 104.5 | 102.1 | 94.7 |

| 2 | 148.8 | 148.8 | 146.5 | 149.5 |

| 3 | 180.2 | 178.2 | 178.4 | 177.4 |

| 4 | 103.4 | 103.6 | 103.3 | 102.4 |

| 5 | 148.2 | 147.4 | 148.8 | 145.6 |

| 6 | 141.9 | 142.1 | 141.8 | 142.1 |

| 7 | 115.9 | 116.0 | 115.7 | 115.8 |

| 8 | 128.8 | 126.7 | 129.4 | 129.9 |

| 9 | 125.2 | 125.5 | 125.4 | 125.5 |

| 10 | 127.9 | 128.0 | 128.5 | 128.4 |

| 11 | 133.7 | 132.5 | 133.3 | 133.1 |

| 12 | 147.3 | 144.5 | 150.1 | 143.9 |

| SOCH3 | 39.0 | |||

| SCH3 | 17.1 |

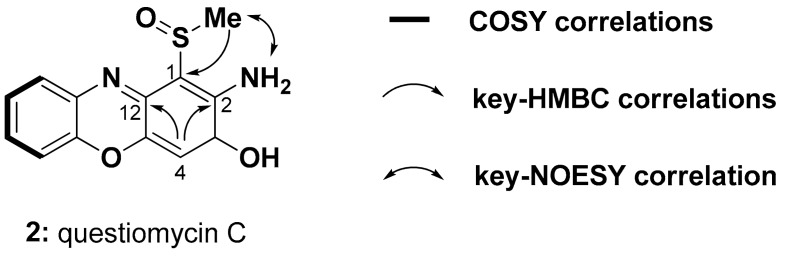

Molecular formula of questiomycin C (2) was deduced as C13H10N2O3S on the basis of its HR-ESI-MS data, which was CH2OS larger than that of compound 1. An NMR spectral profile of 2 was quite similar to that of 1 (Table 1 and Table 2), except one of the two singlet aromatic proton signals corresponding to H-1 or H-4 in 1 was missing in 2. Instead, a methyl singlet was observed at δH 2.98 suggesting that either C-1 or C-4 was substituted by a methyl sulfoxide group. Key HMBC correlations from δH 6.46 (H-4) to C-2 and C-12 indicated that the H-1 in 1 was replaced by the methyl sulfoxide group in 2 (Figure 2). NOESY cross peaks between methyl sulfoxide and NH2 protons (Supplementary Materials Figure S11) assigned the structure of questionamycin C (2) as 2-amino-1-methylsulfoxy-phenoxazin-3-one. An absence of optical rotation suggested that 2 is likely racemic at the chiral center of the sulfoxide group.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional NMR data assignment of questiomycin C (2).

Molecular formula of questiomycin D (3) was determined as C13H10N2O2S from the HR-MS data, which was one oxygen smaller than 2. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra was almost identical with those of 2 (Table 1 and Table 2), but methyl signal was shifted from δH 2.98/δC 39.0 to δH 2.31/δC 17.1. Considering the difference of the chemical shifts as well as molecular formula, it was strongly suggested that methyl sulfoxide group in 2 was replaced by a methyl sulfide group in 3. Detailed analyses of 2D NMR spectra including HMBC and NOESY data revealed the substitution position to be C-1 as 2 (Supplementary Materials Figures S16 and S17). Thus, the structure of questiomycin D (3) was elucidated as 2-amino-1-methylthio-phenoxazin-3-one.

An ESI-MS spectrum of questiomycin E (4) showed molecular ion peaks at m/z 290.95 and 292.95 with nearly same ratio indicating the presence of a bromine atom. The molecular formula for 4 was revealed as C12H7N2O2Br on the basis of HR-ESI-MS data. All NMR spectra including 2D data were very similar to those of 2 and 3 except for an absence of a methyl signal, and the high field shift of C-1 due to the shielding effect of bromine atom. Based on the spectral data above, it was concluded that structure of questiomycin E (4) is 2-amino-1-bromo-phenoxazin-3-one as shown in Figure 1.

Questiomycin A (1) has been reported from various bacterial species including the terrestrial Actinomycete [25], the marine bacteria Halomonas sp. [27], and Actinomadura sp. [26] as a cytotoxic and antibiotic compound. Additionally, compound 1 is known as an allelochemical agent of the terrestrial plants belonging to the family Poaceae, including wheat and corn, to suppress the growth of the competing weeds [28,29]. A 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one (APO) core structure of questiomycins is also found in many bioactive secondary metabolites including grixazone [30], chandrananimycins [26], and actinomycins [31], a clinically used anti-cancer agent.

It is reported that 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one (APO) core structure of bacterial products can be formed by oxidative coupling of two o-aminophenols catalyzed by various types of oxidases [32,33,34]. We therefore supplemented o-aminophenol to the Alteromonas sp. D culture medium to obtain larger amount of questiomycins. As expected, the supplemented culture provided compounds 1 and 4 with the concentration of 7 and 158 times as high as that in the normal conditions, respectively. Compounds 2 and 3, however, were not increased even after supplementation of sulfur sources such as dimethylsulfide and dimethyldisulfide in o-aminophenol enriched medium (Supplementary Materials Figures S23 and S24).

2.2. Biological Activities

Algicidal activity of compounds 1 to 4 was evaluated using C. antiqua (Figure S25). Compounds 1 to 4 showed algicidal activity in concentration-dependent manner, with LC50 values of 0.64, 0.18, 6.37, and 0.20 μM, respectively (Table 3, Figure S26). Although compounds 1, 2, and 4 were equally active, questiomycin D (3), with methylthioether at positin-1 was significantly less active than three other congeners. General toxicity of 1 was evaluated using the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi, the diatom Chaetoceros didymus, the edible red macroalga Bangia fuscopurpurea, the brine shrimp Artemia salina, and the freshwater Medaka fish Oryzias sp. Toxicities of 4 to the brine shrimp were also tested. Compound 1 was toxic to all the organisms tested, especially to microalgae, but it was less toxic to multicellular agla and aquatic animals (Table 3, Figures S27 and S28).

Table 3.

LC50 and 95% confidence interval values of questiomycins against selected microalgae and aquatic organisms (μM).

| Organisms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chattonella antiqua | 0.64 ± 0.19 a | 0.18 ± 0.25 a | 6.37 b | 0.20 ± 0.04 a |

| Karenia mikimotoi | 1.18 c | |||

| Chaetoceros didymus | 0.59 c | |||

| Bangia fuscopurpurea | 25.9 ± 1.32 a | |||

| Artemia salina | 91.7 b | > 68.7 d | ||

| Oryzias sp. | 0.75-7.5 e |

a LC50 ± 95% confidence interval (CI). b 95% CI was not calculatable due to 100% lethal was not observed within the concentration tested. c Concentration at which more than 90% algal cells lysed. d More than half of indibiduals survived at the highest concentration tested. e 10/10 and 0/10 fishes survived for 48 h at 0.75 and 7.5 μM, respectively.

Although 4 was highly toxic to C. antiqua, it did not kill the brine shrimp even at the highest concentration tested (68.7 μM), which is nearly saturated concentration (Table 3, Figure S28). These results showed that the questiomycins have potent lethal activity against microalgae but are less toxic against other aquatic organisms. Interestingly, substitution of C-1 position with bromine atom did not affect the activity against C. antiqua, but toxicity to a crustacean was largely decreased.

2.3. Co-Cultivation of C. antiqua and Alteromonas sp. D

The results from the above experiments strongly suggested that the algicidal action of Alteromonas sp. D is ascribable, at least in part, to compounds 1 to 4; however, these compounds were produced in cultivation conditions completely different from those of the actual marine environment. We thus tested the production of questiomycins and their algicidal actions in the condition similar to those in microalgae blooming environment. C. antiqua was co-cultiured with Alteromonas sp. D in the modified SWM-3 medium where no excessive nutrients were contained. Two days after inoculation, most algal cells died and precipitated on the bottom of the flasks, while the C. antiqua culture without strain D showed normal growth (Figure S29).

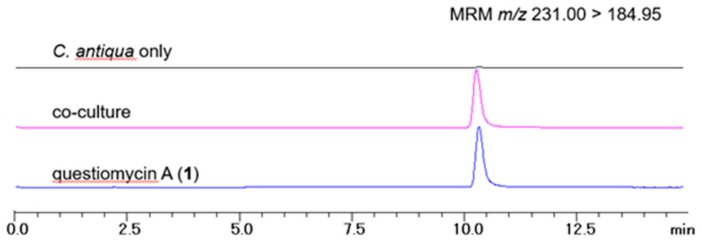

LC-MS analyses of the extracts of the above co-cultivation media and algal cells revealed that compound 1 was indeed produced in the condition similar to the algal blooming sea water (Figure 3). However, its calculated concentration was 0.31 ng/mL (1.46 nM), which is about 400 times lower than LC50 value of compound 1. Note that other questiomycins 2–4 were not detected in this experiment. Although the activity of 1 in two separate set of experiments are not comparable directly, due to differences in initial algal cell density as well as cultivation period, the large difference in the concentration suggested to us some mechanistic insight into the action of 1.

Figure 3.

LC-MS chromatograms of the extracts of C. antiqua culture without strain D (black), co-cultivation (pink), and questiomycin A (1) standard (blue). Calculated concentration of compound 1 in co-cultivation medium was 0.31 ng/mL.

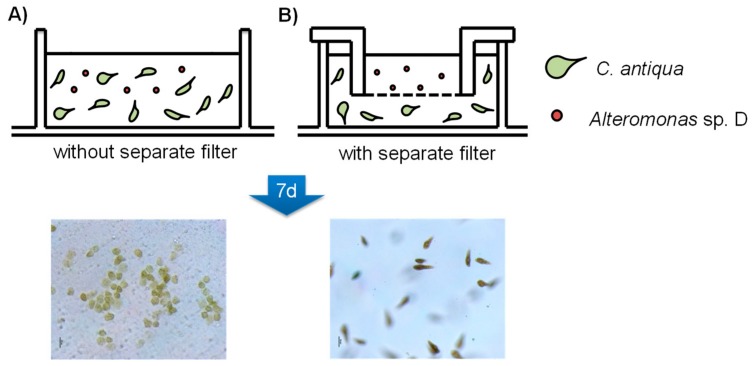

We therefore hypothesized that the significant difference between the LC50 value and detected concentration of 1 in the above experiment is due to production of algicidal materials other than questiomycics by Alteromonas sp. D, or the strain D produced 1 upon close proximity to the microalgae, and topical action of 1 lead to lyse the algal cells [35,36]. In the latter case, Alteromonas sp. D can kill C. antiqua only in contact with the algal cells, but not under the condition where the bacterium was separated from the alga by semipermeable membrane. To test this idea, C. antiqua and strain D was co-cultivated with or without separation membrane (Figure 4), in that the bacterium and algae can freely contact physically and chemically in condition-A, but in condition-B, only chemical contact was possible between the organisms. After seven days from bacterium inoculation, all C. antiqua cells lysed in the condition-A wells, however cells in the condition-B survived (Figure 4). LC-MS analyses showed that concentration of 1 in the condition-A media was 1.5 nM, which was nearly identical to the previous co-cultivation experiment, while that in the condition-B medium was less than detection limit, indicating that no or trace amount of questiomycins were produced in the separated culture (Figure S30).

Figure 4.

Co-cultivation of Alteromonas sp. D and C. antiqua without separate filter (A) and co-cultivation with separate filter (B). Pore size 0.4 μm membrane was used.

These results could not rule out the possibility of presence of the alternative algicidal molecules, but strongly supported an idea that physical contact between microalga and algicidal bacterium would be one of the triggers to produce algicidal molecules such as questiomycins under the oligotrophic environment, and thus only a small amount of algicidal compound is enough to kill the cells in contact. This mechanism is apparently cost efficient for the algicidal bacterium, and also beneficial for using the strain for preventing HAB due to the fact that the least amount of toxic molecules would spread in the environment. Mechanisms of algicidal activity by questiomycins as well as biosynthetic regulation of algicidal molecules in the bacterium are intriguing questions to be answered. Furthermore, the presence and function of questiomycins in actual environment need to be investigated. Nevertheless, our findings, identification of the algicidal molecules in the algicidal bacteria, would be of great help to further understand the chemical-ecological phenomena occurring in HAB.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

The 1D and 2D NMR data including 1H, 13C, COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY spectra were recorded on a JNM-ECZ400S/L1 NMR spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C using the default pulse-sequence parameters preset in the spectrometer. Chemical shifts of 1H NMR spectra were referenced to the solvent peaks: δH 2.49 and δC 39.5 for DMSO-d6. Preparative and analytical HPLC were performed with a Prominence HPLC system equipped with photodiode array detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). LC-MS analyses were carried out with an LCMS-8040 LC-MS system (Shimadzu). High-resolution electrospray mass spectra (HRESIMS) were obtained on a Sciex Triple TOF+5600 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). UV spectra were measured on a SpectraMax M2 UV spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, California, USA). Cell density of C. antiqua were measured by 10-AU Fluorometer (Turner Design, San Jose, California, USA). All chemicals were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka, Japan), Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan), or Takara Bio (Shiga, Japan), except for those specifically mentioned.

3.2. Biological Materials

Alteromonas sp. D (16S rRNA sequence: accession number AB040466) was isolated from sea water of Hiroshima-bay (Hiroshima, Japan) in 1991 [11]. The strain was deposited as glycerol stock until use. An axenic strain of the raphidophycean flagellate C. antiqua (NIES-1, provided from the National Institute for Environmental Study) was used. Algal strain was maintained in the modified SWM-3 medium (Table S2) at 20 °C under a light intensity of 50–100 μmol photons m−2s−1 using a 14:10 h light–dark photocycle. Axenic culture of the dinoflagellate K. mikimotoi and the diatom C. didymus were maintained in the modified SWM-3 medium, and incubated under 14 h light, 10 h dark photocycle condition at 22 °C. Filamentous red-macroalgae, B. fuscopurpurea, was maintained in artificial sea water at 20 °C. Cysts of the brine shrimp, A. salina, were purchased from Japan Pet Design (Tokyo, Japan) and kept at 4 °C until use. The Medaka fish, Oryzias sp., were purchased from a market in Hakodate city and kept at 20 °C.

3.3. Cultivation of Bacterium, Extraction, and Isolation of Algicidal Compounds

Alteromonas sp. D was pre-cultured in 10 mL ST medium (trypton 5 g/L, yeast extract 0.5 g/L in artificial sea water), inoculated into ST medium (200 mL in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks, 8 flasks in total), and was shaken (215 rpm) for four days at 25 °C. The conditioned medium was centrifuged, and the supernatant was passed through C18 reversed-phase column (5 × 20 cm), eluting with 0%, 20%, 50%, and 70% aqueous MeOH (500 mL each), then by 100% MeOH (500 mL). Fractions eluted with 70 and 100% MeOH were combined and concentrated, followed by fractionated by a gel filtration column using Sephadex LH-20 (4 × 100 cm, GE Helthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) using MeOH as an eluent. An active fraction obtained as an orange-colored band was further purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Develsil C30-UG-5, Nomura Chemical, Aichi, Japan; gradient elution of 32–100% MeOH) to afford compound 1 (1.25 mg) as a major active compound. From a large-scale (4 L) culture, three new compounds, 2 (1.51 mg), 3 (1.03 mg), and 4 (0.79 mg) along with 1 (13.1 mg) were isolated.

Questiomycin C (2): Orange powder; UV (DMSO) λmax 230 nm (ε 5.00 × 104), 428 nm (ε 1.85 × 104); NMR data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HR-ESIMS m/z 275.0482 (M + H)+ (calcd. for C13H11N2O3S, –0.8 mmu).

Questiomycin D (3): Orange powder; UV (DMSO) λmax 228 nm (ε 6.76 × 104), 428 nm (ε 1.97 × 104); NMR data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HR-ESIMS m/z 259.0537 (M + H)+ (calcd. for C13H11N2O2S, –0.4 mmu).

Questiomycin E (4): Orange powder; UV (DMSO) λmax 241 nm (ε 2.54 x 104), 426 nm (ε 2.54 × 104); NMR data, see Table 1 and Table 2; HR-ESIMS m/z 290.9757 (M + H)+ (calcd. for C12H8N2O2Br, –1.2 mmu).

3.4. Preparation of Questiomycin A (1) and E (4) by Supplemented Fermentation with o-Aminophenol

Filter sterilized ethanol solution of o-aminophenol was added (final concentration 100 mg/L) into Alteromonas sp. D overnight culture (0.2 L of 1/2-ST medium; trypton 2.5 g/L, yeast extract 0.25 g/L in artificial sea water), then further shaken for four days at 28 °C (180 rpm). Cultured broth was subjected to the repetitive fractionation including C18 column chromatography, Sephadex LH20 size exclusion chromatographym, and silica gel column chromatofgraphy to obtain compound 1 (4.5 mg) and 4 (6.2 mg). These materials were used for biological assays.

3.5. Algicidal Assay Using C. antiqua

The axenic cultures of C. antiqua was diluted with modified SWM-3 medium (Table S2) to a cell density of 1–3 × 103 cells mL−1, and 0.8 mL aliquots were transferred into each well of sterilized 48-well microtiter plates, and kept for 1 day. Then, 8 μL of test samples (1 mg/mL in DMSO) were added to the wells, and then incubated for 1 week. Pure DMSO was used as a negative control. Each well was observed daily with an inverted microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE TE200, Tokyo, Japan). Algicidal activity was evaluated based on the change of the cell morphology and motility and used for activity guided separation.

For quantification assay, 4 μL of test samples (1.000, 0.333, 0.111, 0.370, 0.123, 0.041 μg/mL in DMSO) were added to the test tubes containing C. antiqua culture (4 mL of 3 × 103 cells/mL), and then the tubes were incubated for seven days under the same condition above. Pure DMSO (4 μL) was used as a control. Cell density was monitored by measuring autofluorescence of live motile cells using 10AU Fluorometer. Medium without alga was used as background. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The LC50 and 95% confidence interval values were calculated using GraphPadPrism8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) with non-linear four parameter logistic regression (vs. log concentration) to the sigmoid curve by non-linear least squares.

3.6. Algicidal Assay against Karenia mikimotoi and Chaetoceros didymus

Axenic culture of the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi and the diatom Chaetoceros didymus were diluted with a modified SWM-3 medium (1–3 × 103 cells mL−1), and 792 μL aliquots were transferred into wells of 48-well microtiter plates and incubated at 22 °C overnight. Two-fold serial dilution of the test compound (8 μL of 1.000, 0.500, 0.250, 0.125, 0.063, 0.031,0.016, 0.008 mg/mL in DMSO) was added to each well, and then incubated further for seven days. Microscopic observation was carried out using the inverted microscope to observe cell mortility and morphology. Algal cells, which lost mortility and had observable deformation including cytosol shrinking or leakage, loss of chrolophyl, burst of the thecal plates, or frustules, were counted as dead cells (Figure S27). All tests were done in triplicate.

3.7. Artemia salina Assay

Artemia salina (brine shrimp) eggs were inoculated in sea water with aeration at room temperature for 24 hours. Hatched larvae were transferred into 24-well plates containing 792 μL sea water (10 larvae/well), then 8 μL of test samples (compounds 1 and 4; 2.000, 1.000, 0.500, 0.250, 0.125, 0.625 mg/mL in DMSO) were added. Pure DMSO (8 μL) was used as a negative control. Plates were incubated at 15 °C for 48 h, then the number of the survived larvae was counted. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The LC50 value was calculated by the same way descrived in Section 3.5.

3.8. Bangia fuscopurpurea Assay

The filamentous red-macroalga, Bangia fuscopurpurea, was suspended in 24-well plates containing 792 μL of artificial sea water, then 8 μL of compound 1 (2.000, 1.000, 0.500, 0.250, 0.125, 0.625 mg/mL in DMSO) was added, then incubated at 15 °C for 4 days with 14 h light–10 h dark photocycle. Pure DMSO (16 μL) was used as a negative control. The cells of B. fuscopurpurea were dyed by soaking in erythrosine B solution (0.1 mg/mL in artificial sea water), and number of the pink colored dead cells and the green colored live cells were counted under microscope. Experiments were done in triplicate. The LC50 and 95% confidence interval values were calculated by the same way descrived in Section 3.5.

3.9. Oryzias sp. Assay

After taming Oryzias sp. (Medaka fish) in plastic containers for 2 days at 20 °C, 10 individuals were transferred into each test tank containing 1.0 L water. Compound 1 (1.6 mg/mL in DMSO) was added at the final concentrations of 1.6, 0.16, and 0.016 μg/mL, respectively. Tanks were kept at 20 °C and observed for 48 hours, and number of live fish was counted. This experiment was performed once.

3.10. Co-Cultivation Assay

The colony of Alteromonas sp. D on an agar plate was picked by sterilized needle and inoculated in the early stationary phase C. antiqua culture (3 × 104 cells/mL, 20 mL modified SWM-3 medium in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks), then incubated for 2 days under the same culture conditions described above. Then, whole medium was transferred to the centrifuge bottles and separated to cell pellet and supernatant by centrifugation. The resulting cell pellet was extracted with EtOH (10 mL). Supernatant was subjected to solid phase extraction by Sep-Pak C18 short columns (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Short columns were washed with distilled water (5 mL), and eluted by MeOH (10 mL). Both cell pellet and supernatant extracts were combined, dried in vacuo, and re-dissolved in MeOH (10 mg/mL) to prepare LC-MS samples. A culture of C. antiqua with the same condition except for absence of Alteromonas sp. D was used as a negative control. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

3.11. LC-MS Quantiative Analysis

The samples prepared above were analyzed by LC-MS in multiple-reaction-monitoring (MRM) mode using the following conditions; column: Develosil RPAQUEOUS (2.0 × 100 mm, Nomura Chemical); flow rate: 0.2 mL/min; solvents: 30% aqueous MeOH to 100% MeOH containing 0.2% AcOH; MRM condition: precursor ion m/z 213.00 (M+H)+, daughter ion m/z 184.95 (M + H)+, collision energy –20 eV. Peak area was measured using the LC-solutions software (Shimadzu). Concentration of questiomycin A (1) in each sample was determined from the standard curve prepared from purified 1 as an authentic material.

3.12. Membrane Filter Separated Cultivation Assay

The cells of C. antiqua at early stationary phase were transferred to 6-well plates (1.3 × 104 cells/mL, 7 mL/well), then wells of one group (group B) were covered by TC-insert filters (pore size 0.4 μm, Sarstedt, Tokyo, Japan) to separate inner and outer wells. After overnight incubation at 20 °C using a 14:10 h light–dark photocycle, the culture of Alteromonas sp. D (25 °C overnight in ST-medium, 1.4 μL) was inoculated in the wells of group A and inner wells of group B, then kept for 7 days. After evaluation of the cell morphorogy in each well under microscopic observation, conditioned media were recovered and extracted in the same manner described above, and re-dissolved in MeOH (200 μL) for the LC-MS analysis. All tests were performed in triplicate.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, questiomycin A (1-aminophenoxazine-3-one, (1)) and three new derivatives 2–4 were identified from the culture of the algicidal bacterium, Alteromonas sp. D, and compound 1–4 were shown to have potent algicidal activity. Compound 1 was also produced even in an oligotrophic medium, only when co-cultivated with C. antiqua. These observations suggested that the algicidal bacterium, Alteromonas sp. D, require close contact to prey microalgae to initiate biosynthesis of questiomycins in the oligotrophic environment. Local accumulation of the algicidal compound may trigger cell lysis although detailed mechanism is yet to be investigated. The contact-initiated production mechanism proposed here would be beneficial for algicidal bacteria to lyse algal cells using minimal production of secondary metabolites, and components in the lyzed cell can be utilized by bacterium. Further understanding of chemical and ecological processes between algicidal bacteria and blooming algae, especially in natural environment, is necessary to utilize this ecologically friendly strategy for preventing HAB.

Acknowledgments

Strain of Bangia fuscopurpurea was kindly provided by Koji Mikami of Graduate School of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University.

Supplementary Materials

The following materials are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/24/24/4522/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (DMSO-d6), Figure S2: 13C NMR spectrum of 1 (DMSO-d6), Figure S3: COSY spectrum of 1 (DMSO-d6), Figure S4: HSQC spectrum of 1 (DMSO-d6), Figure S5: HMBC spectrum of 1 (DMSO-d6), Figure S6: 1H NMR spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S7: 13C NMR spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S8: COSY spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S9: HSQC spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S10: HMBC spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S11: NOESY spectrum of 2 (DMSO-d6), Figure S12: 1H NMR spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S13: 13C NMR spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S14: COSY spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S15: HSQC spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S16: HMBC spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S17: NOESY spectrum of 3 (DMSO-d6), Figure S18: 1H NMR spectrum of 4 (DMSO-d6), Figure S19: 13C NMR spectrum of 4 (DMSO-d6), Figure S20: COSY spectrum of 4 (DMSO-d6), Figure S21: HSQC spectrum of 4 (DMSO-d6), Figure S22: HMBC spectrum of 4 (DMSO-d6), Figure S23: LCMS chromatogram of Alteromonas sp. D culture broth supplemented with o-aminohenol and dimethylsulfide, Figure S24: LCMS chromatogram of Alteromonas sp. D culture broth supplemented with o-aminohenol and dimethyldisulfide, Figure S25: Cell morphology of live and dead cells of C. antiqua, Figure S26: Results of quantitative algicidal assay of questiomycins, Figure S27: Morphology of K. mikimotoi and C. didymus treated with lethal does of 1, Figure S28: Morphological change of selected microalgae over questiomycin A (1), Figure S29: Picture of C. antiqua culture co-cultivation with or without Alteromonas sp. D, Figure S30: LCMS chromatograms of the extract of co-culture (A) and separate-culture (B) in 6 well plates, Table S1: Literature NMR data of compound 1, Table S2: Recipe of the modified SWM-3 medium, Table S3: method and results of questiomycin A (1) plate absorption test. Raw NMR data (FID) are available at https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/24/24/4522/s2.

Author Contributions

S.U. conducted the cultivation, compounds isolation and structure elucidation, biological assays, and LC-MS analyses. M.K. performed biological assays and co-cultivation assay. I.I. provided algae and bacterium strains and supported the algae cultivation. R.S. provided advices in manuscript preparation. M.J.F. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI [15H05629] and MEXT KAKENHI [25108701].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1 and 4 are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Trainer V.L., Bates S.S., Lundholm N., Thessen A.E., Cochlan W.P., Adams N.G., Trick C.G. Pseudo-nitzschia physiological ecology, phylogeny, toxicity, monitoring and impacts on ecosystem health. Harmful Algae. 2012;14:271–300. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heisler J., Glibert P.M., Burkholder J.M., Anderson D.M., Cochlan W., Dennison W.C., Dortch Q., Gobler C.J., Heil C.A., Humphries E., et al. Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: A scientific consensus. Harmful Algae. 2008;8:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells M.L., Trainer V.L., Smayda T.J., Karlson B.S.O., Trick C.G., Kudela R.M., Ishikawa A., Bernard S., Wulff A., Anderson D.M., et al. Harmful algal blooms and climate change: Learning from the past and present to forecast the future. Harmful Algae. 2015;49:68–93. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouakou C.R.C., Poder T.G. Economic impact of harmful algal blooms on human health: A systematic review. J. Water Health. 2019;17:499–516. doi: 10.2166/wh.2019.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grattan L.M., Holobaugh S., Morris J.G., Jr. Harmful algal blooms and public health. Harmful Algae. 2016;57:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inaba N., Imai I., Trainer Vera L., Onishi Y., Ishii K.-I., Wyllie-Echeverria S. Algicidal and growth-inhibiting bacteria associated with seagrass and macroalgae beds in Puget Sound, WA, USA. Harmful Algae. 2017;62:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueroa R.I., Estrada M., Garces E. Life histories of microalgal species causing harmful blooms: Haploids, diploids and the relevance of benthic stages. Harmful Algae. 2018;73:44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson Donald M. Approaches to monitoring, control and management of harmful algal blooms (HABs) Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2009;52:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano K., Lee T.J., Matsumura M. In situ algal bloom control by the integration of ultrasonic radiation and jet circulation to flushing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:4941–4946. doi: 10.1021/es010711c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun R., Sun P., Zhang J., Esquivel-Elizondo S., Wu Y. Microorganisms-based methods for harmful algal blooms control: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;248:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imai I., Ishida Y., Sakaguchi K., Hata Y. Algicidal marine bacteria isolated from northern Hiroshima Bay, Japan. Fish. Sci. 1995;61:628–636. doi: 10.2331/fishsci.61.628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demuez M., Gonzalez-Fernandez C., Ballesteros M. Algicidal microorganisms and secreted algicides: New tools to induce microalgal cell disruption. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33:1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer N., Bigalke A., Kaulfuss A., Pohnert G. Strategies and ecological roles of algicidal bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017;41:880–899. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayali X., Azam F. Algicidal bacteria in the sea and their impact on algal blooms. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2004;51:139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J.-H., Yoshinaga I., Nishikawa T., Imai I. Algicidal bacteria in particle-associated form and in free-living form during a diatom bloom in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2010;60:151–161. doi: 10.3354/ame01416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba N., Nagai S., Sakami T., Watanabe T., Araki K., Kawasaki S., Imai I. Temporal variability of algicidal and growth-inhibiting bacteria at an eelgrass bed in the Ariake Sea, Japan. Biorem. J. 2018;22:112–125. doi: 10.1080/10889868.2018.1516613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onishi Y., Mohri Y., Tuji A., Ohgi K., Yamaguchi A., Imai I. The seagrass Zostera marina harbors growth-inhibiting bacteria against the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense. Fish. Sci. 2014;80:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s12562-013-0688-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul C., Pohnert G. Interactions of the algicidal bacterium Kordia algicida with diatoms: Regulated protease excretion for specific algal lysis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S.-O., Kato J., Takiguchi N., Kuroda A., Ikeda T., Mitsutani A., Ohtake H. Involvement of an extracellular protease in algicidal activity of the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. Strain A28. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:4334–4339. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4334-4339.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J.-D., Kim J.-Y., Park J.-K., Lee C.-G. Selective control of the Prorocentrum minimum harmful algal blooms by a novel algal-lytic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis AFMB-008041. Mar. Biotechnol. 2009;11:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s10126-008-9167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y., Lei X., Zhu H., Zhang H., Guan C., Chen Z., Zheng W., Fu L., Zheng T. Chitinase producing bacteria with direct algicidal activity on marine diatoms. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21984. doi: 10.1038/srep21984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D., Kim J.F., Yim J.H., Kwon S.-K., Lee C.H., Lee H.K. Red to red—The marine bacterium Hahella chejuensis and its product prodigiosin for mitigation of harmful algal blooms. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;18:1621–1629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong S.-Y., Ishida K., Ito Y., Okada S., Murakami M. Bacillamide, a novel algicide from the marine bacterium, Bacillus sp. SY-1, against the harmful dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8005–8007. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.08.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho J.Y. Algicidal activity of marine Alteromonas sp. KNS-16 and isolation of active compounds. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012;76:1452–1458. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anzai K., Isono K., Okuma K., Suzuki S. The new antibiotics, questiomycins A and B. J. Antibiot. 1960;13:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maskey R.P., Li F.C., Qin S., Fiebig H.H., Laatsch H. Chandrananimycins A–C: Production of novel anticancer antibiotics from a marine Actinomadura sp. Isolate M048 by variation of medium composition and growth conditions. J. Antibiot. 2003;56:622–629. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitzer J., Grosse T., Wang L., Lang S., Beil W., Zeeck A. New aminophenoxazinones from a marine Halomonas sp.: Fermentation, structure elucidation, and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 2006;59:86–92. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gents M.B., Nielsen S.T., Mortensen A.G., Christophersen C., Fomsgaard I.S. Transformation products of 2-benzoxazolinone (BOA) in soil. Chemosphere. 2005;61:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Understrup A.G., Ravnskov S., Hansen H.C.B., Fomsgaard I.S. Biotransformation of 2-benzoxazolinone to 2-amino-(3h)-phenoxazin-3-one and 2-acetylamino-(3h)-phenoxazin-3-one in soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005;31:1205–1222. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-4257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi Y., Furusho Y., Higashi T., Chun H.-K., Furihata K., Sakuda S., Horinouchi S. Structures of grixazone A and B, A-factor-dependent yellow pigments produced under phosphate depletion by Streptomyces griseus. J. Antibiot. 2004;57:218–223. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauger A.B., Lackner H. The actinomycins. In: Cragg G.M., Kingston D.G.I., Newman D.J., editors. Anticancer Agents from Natural Products. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2012. pp. 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki H., Furusho Y., Higashi T., Ohnishi Y., Horinouchi S. A novel o-aminophenol oxidase responsible for formation of the phenoxazinone chromophore of grixazone. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:824–833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller U., Lang M., Crnovcic I., Pfennig F., Schauwecker F. The actinomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces chrysomallus: A genetic hall of mirrors for synthesis of a molecule with mirror symmetry. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2583–2595. doi: 10.1128/JB.01526-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washington C., Maxwell J., Stevenson J., Malone G., Lowe E.W., Zhang Q., Wang G., McIntyre N.R. Mechanistic studies of the tyrosinase-catalyzed oxidative cyclocondensation of 2-aminophenol to 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;577:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul C., Mausz M.A., Pohnert G. A co-culturing/metabolomics approach to investigate chemically mediated interactions of planktonic organisms reveals influence of bacteria on diatom metabolism. Metabolomics. 2013;9:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0453-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smriga S., Fernandez V.I., Mitchell J.G., Stocker R. Chemotaxis toward phytoplankton drives organic matter partitioning among marine bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:1576–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512307113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.