Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Our aim was to examine whether surgery with regional anesthesia (RA) is associated with accelerated long-term cognitive decline comparable to that previously reported following general anesthesia (GA).

METHODS:

Longitudinal cognitive function was analyzed in a cohort of 1,819 older adults. Models assessed the rate of change in global and domain-specific cognition over time in participants exposed to RA or GA.

RESULTS:

When compared to those unexposed to anesthesia, the postoperative rate of change of the cognitive global z-score was greater in those exposed to both RA [difference in annual decline of −0.041, P=.011] and GA [−0.061, P<.001]; these rates did not differ. In analysis of the domains-specific scores, an accelerated decline in memory was observed after GA (−0.065, P<.001) but not RA (−0.011, P=.565)

CONCLUSIONS:

Older adults undergoing surgery with RA experience decline of global cognition similar to those receiving GA; however memory was not affected.

Keywords: Anesthesia: regional, general; Cognitive aging; Cognitive z-scores; Global cognitive scores; Domains: memory, attention/executive function, language, visuospatial skills; Mayo Clinic Study of Aging; Older adults; Surgery

1. Introduction

Preclinical studies show the exposure of adult rats to the anesthetic isoflurane is associated with amyloid β-protein accumulation consistent with the neuropathology observed in Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) [1–3]. This has raised concerns that exposure of patients to volatile anesthetics may promote long-term cognitive impairment [3]. Studies examining the association between anesthesia and cognition employ a variety of designs and outcomes, and have drawn varying conclusions [4–11]. Using the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA), we reported that exposure to surgery requiring general anesthesia (GA) was not associated with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia [6–8]. However, in these studies longitudinal cognitive assessments were not examined. Examining cognitive trajectories could be a more sensitive means to detect potential associations between anesthesia and cognitive decline, compared with meeting a particular threshold needed to diagnose MCI or dementia. Indeed, when cognitive trajectories were used in the MCSA, exposure to surgery with GA was associated with a modest acceleration of the cognitive decline that exceeded that observed in participants not exposed to GA (GA naïve participants) [12]. A primary limitation of these and similar studies is that anesthesia in humans is administered in the context of a concurrent procedure, making it difficult to make causal inferences regarding anesthesia given the potential confounding variables, including indication bias and surgical trauma.

If inhalational agents used for GA are the primary cause for neurodegeneration associated with long-term cognitive decline, then avoiding GA by conducting surgery with regional anesthesia (RA) could mitigate this effect. Furthermore, local anesthetics can attenuate several mechanisms implicated in the development of neurodegeneration: postoperative stress, immune responses, and the release of inflammatory mediators [13, 14]. However, most previous studies that compared the effects of RA and GA on cognition focused on short-term outcomes [15, 16], and data on longer-term changes in cognition are limited [4, 17].

The objective of the present study is to extend our prior analysis of elderly patients exposed to GA [18] and determine the cognitive function of MCSA participants after surgery with RA. We examined longitudinal postoperative cognition by assessing changes in global and domain-specific cognitive z-scores (memory, attention/executive function, language, and visuospatial skills) over years following exposure to surgery and anesthesia. We hypothesized that the cognitive trajectories of patients exposed to RA would not differ from GA naïve participants.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, Rochester, Minnesota. At enrollment, all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

2.1. Selection of Participants

Study participants were enrolled in the MCSA, a population-based epidemiologic study examining risk factors for MCI and dementia among Olmsted County residents [19] The present study included MCSA participants who were 1) aged 70 through 91 at baseline assessment conducted from November 2004 through November 2009, 2) were not demented at baseline assessment (i.e., those without cognitive impairment or who had MCI were included), and; 3) who had at least 1 follow-up MCSA visit after baseline assessment.

2.2. Identification of Anesthetic and Surgical Episodes

All surgeries or procedures performed with RA or GA occurring after MSCA enrollment and within 20 years prior to enrollment were identified using the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical record linkage system [20]. RA included neuraxial blocks (epidural and spinal anesthesia), and peripheral nerve blocks (axillary, interscalene, ankle blocks, etc.). Surgical field infiltration with local anesthetic alone was not considered as RA. GA combined with regional analgesia for pain management was considered for purposes of primary analysis as GA. Agents used during GA and sedatives (e.g., propofol, benzodiazepines) given during RA were recorded.

2.3. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Information on how demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained has been previously reported [19]. Briefly, self-reported medical history obtained at the initial MCSA visit was corroborated using information from the REP medical records-linkage system [19–21]. Variables used as adjustment covariates included sex; baseline age; education; APOE ε4 status; midlife diabetes; midlife hypertension; midlife dyslipidemia (midlife is defined prior to age 65); atrial fibrillation; Charlson Comorbidity Index (updated at each MCSA visit); history of congestive heart failure; stroke; coronary artery disease; marital status; smoking status; and diagnosed alcohol problem. These covariates were chosen based on prior studies as associated with cognitive scores [22]. Of note, differences between anesthetic agents used for GA or RA block location (or type of local anesthetic) were not used as adjustment covariates in any analyses.

2.4. Cognitive Assessments

Details of the clinical evaluation at baseline and at each 15-monthly follow-up have been described previously [19]. Briefly, the evaluation included assessment of each participant’s demographic information, medical history, years of education, memory (self-report) and APOE genotyping. The neurologic evaluation by a physician included the Short Test of Mental Status [23], a modified Hachinski Ischemic Scale [24, 25], a modified Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale [26], and a neurologic examination. The neuropsychological evaluation included assessment of 4 cognitive domains using 9 tests: 1) attention/executive domain (Trail Making Test B and Digit Symbol Substitution Test) [27, 28]; 2) language (Boston Naming Test [29] and Category Fluency) [30]; 3) memory domain (Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory II [delayed recall], Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Visual Reproduction- II [delayed recall] [31], and Auditory Verbal Learning Test (delayed recall) [32]; and 4) visuospatial skills (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Picture Completion test and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Block Design test) [27]. Cognitive scores are commonly expressed as z-scores, which denote how many standard deviations are between a given score and the mean value of a set of scores derived from reference data. To compute domain z-scores and overall global cognitive z-score, means and standard deviations of raw test scores (completed at the enrollment visit) for participants who were cognitively unimpaired in the MCSA 2004 enrollment cohort (n = 1,969) were used as the reference distribution [19, 33]. Test scores were scaled by their standard deviation and domain-specific z-scores were calculated by averaging scaled test scores. A global cognitive summary z-score was estimated by averaging the 4 domain z-scores and scaling by the standard deviation [19, 33]. Individuals in the present study represent a subset of the 2004 enrollment cohort and the additional participants enrolled through November 2009 (Figure 1). Thus, not all of the participants included in this analysis are represented in the reference sample used to calculate z-scores.

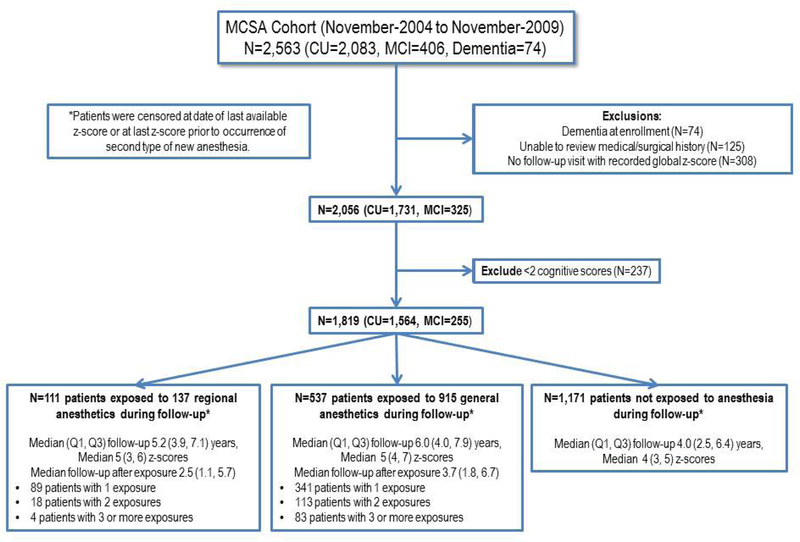

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) participants in the current analysis. CU, cognitively unimpaired; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

2.5. Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome of interest was global z-score. This measure was chosen because it is an aggregate of the domain-specific measures, and may have less error in measurement compared to individual domain scores. Domains-specific z-scores (memory, attention/executive function, language, and visuospatial skills) were analyzed as secondary outcomes. We assessed whether exposure to RA or GA is associated with an accelerated decline in cognitive scores over time (i.e. slope) compared to unexposed, GA naïve participants. The relationship was estimated using longitudinal assessments of cognitive scores, fitted using linear mixed effects models that allow for a change in slope following post-enrollment exposure to RA or GA.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Patient characteristics at MCSA enrollment were described as mean (standard deviation) or median (25th, 75th) percentiles for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables according to exposure status during follow-up. The type of anesthesia and the characteristics of the surgical procedures were categorized based on the first exposure when patients had more than one exposure.

A detailed statistical description of the regression models is provided in Supplemental Content 2. Regression models were separately estimated for the outcomes of global z-score and the four domain-specific z-scores. In brief, the model for global z-score included variables associated with the slope or rate of change in global z-scores over time: time following MCSA enrollment, time following post-enrollment GA exposure, and time following post-enrollment RA exposure. These variables estimate the post-MCSA enrollment slope prior to a post-enrollment anesthesia exposure, change in slope following post-enrollment GA, and change in slope following post-enrollment RA, respectively. Time following post-enrollment RA exposure is a time-dependent variable that is zero in patients prior to a post-enrollment surgery with RA. When a subject has a post-enrollment exposure to RA, the variable begins counting time since the RA. Time following post-enrollment GA was defined similarly. Follow up was censored for patients who received a different type of anesthetic management during follow up, such that post-enrollment change in slope was estimated using only the first type of exposure after enrollment. Thus, if a patient had GA at 1 year after enrollment and RA at 4 years after enrollment, they would be summarized descriptively as a GA patient and in regression models their follow up would be censored at 4 years. Regression models were similarly defined for each of the four domain-specific z-scores.

Each regression model further included adjustment for demographic and clinical variables at MCSA enrollment as described previously, as well as MCI at enrollment, and indicators of prior exposure to surgery with RA and prior exposure to surgery with GA in the 20 year period prior to enrollment. Regression models were adjusted for these covariates and their interactions with time, i.e. adjusting for their contribution to baseline global z-score at MCSA enrollment and post-enrollment slope of global z-score prior to new RA or GA. Missing data was rare (<1% of participants) and complete case analysis was performed excluding participants with missing covariates from regression models. These linear mixed effects models included subject-specific random intercepts and random slopes; random terms were assessed with likelihood ratio tests, which suggested that the model including both fit the data better than a reduced model. Results are summarized by presenting 1) slope estimates for patients not exposed to anesthesia after enrollment, and 2) the estimated difference in slope associated with each type of exposure (compared with those not exposed).

Since the use of RA is not feasible in certain types of procedures, the comparison between regional and general surgical anesthesia is potentially confounded by the type of surgery. Therefore, we performed sensitivity analyses to assess changes in cognitive function following orthopedic surgery using RA or GA. For individuals who underwent non-orthopedic procedures following enrollment, follow up was censored at the time of the non-orthopedic procedure. Additional sensitivity analysis included assessing whether RA or GA in the 20 years prior to enrollment modifies the relationship between post-enrollment exposures and cognitive decline by including interactions between prior-to-enrollment exposures and time after post-enrollment exposures. Using these interactions, we estimated the post-enrollment RA or GA association among those without prior exposure in the prior 20 years before MCSA enrollment. Finally, our main analysis classified procedures performed using GA combined with RA as GA. As a sensitivity analysis we repeated the analysis for the global z-score using three exposure levels, GA, RA and combined GA+RA.

Analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (Version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary). A P <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical comparisons for domain-specific cognitive scores were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population, Anesthetic Exposure and Follow-up

Of the 2,563 individuals who were enrolled in the MCSA during the study period, 744 were excluded (Figure 1), resulting in a total of 1,819 MCSA participants. Of these, 1,564 (86%) had normal cognitive function and 255 (14%) had MCI at enrollment.

Patients were classified according to the primary anesthetic technique received at the first post-enrollment exposure to surgery with anesthesia (GA or RA), or as having no post-enrollment exposure: 111 were exposed to RA (137 total anesthetics), 537 were exposed to GA (915 total anesthetics), and 1,171 were GA naïve (Figure 1). The median (Q1, Q3) follow-up in those with no subsequent exposure to anesthesia was 4.0 (2.5, 6.4) years. For those exposed to RA and GA the mean follow-up after enrollment was 5.2 [3,9–7.1] and 6 [4–7,9] years, respectively, with follow up after exposure of 2.5 (1.1, 5.7) and 3.7 (1.8, 6.7), respectively for RA and GA.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at enrollment were similar among exposure categories (Table 1). Overall, 1,201 patients (66%) had been exposed to anesthesia in the 20 years prior to enrollment. Participants received a total of 1,052 anesthetics after enrollment but prior to any censoring (Table 2). Regional techniques were approximately balanced between peripheral nerve and central neuraxial blocks. Most patients receiving RA underwent orthopedic surgery, and received adjuvant propofol, opioids, and benzodiazepines. Most patients receiving GA received propofol, opioids, and volatile anesthetics.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics collected at enrollment by anesthetic exposure prior to censoring*

| Characteristic | Overall (N=1,819) |

No Anesthesia (N=1,171) |

General Anesthesia (N=537) |

Regional Anesthesia (N=111) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years† | 78.9 (5.1) | 79.4 (5.3) | 77.9 (4.7) | 78.0 (5.0) |

| Sex† | ||||

| Male | 944 (52%) | 589 (50%) | 304 (57%) | 51 (46%) |

| Female | 875 (48%) | 582 (50%) | 233 (43%) | 60 (54%) |

| Education, years | ||||

| Less than 12 years | 167 (9%) | 116 (10%) | 48 (9%) | 3 (3%) |

| 12 years | 611 (34%) | 397 (34%) | 178 (33%) | 36 (32%) |

| 13–15 years | 452 (25%) | 289 (25%) | 135 (25%) | 28 (25%) |

| 16 years and above | 589 (32%) | 369 (32%) | 176 (33%) | 44 (40%) |

| Smoking status† | ||||

| Never | 958 (53%) | 637 (54%) | 261 (49%) | 60 (54%) |

| Former | 797 (44%) | 489 (42%) | 260 (48%) | 48 (43%) |

| Current | 64 (4%) | 45 (4%) | 16 (3%) | 3 (3%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 175 (10%) | 119 (10%) | 44 (8%) | 12 (11%) |

| Married | 1,169 (64%) | 721 (62%) | 373 (69%) | 75 (68%) |

| Widowed | 475 (26%) | 331 (28%) | 120 (22%) | 24 (22%) |

| APOE-ε4 genotype, n=1,816 | 484 (27%) | 301 (26%) | 156 (29%) | 27 (24%) |

| History of alcohol problem, n=1,816 | 69 (4%) | 42 (4%) | 25 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 169 (9%) | 106 (9%) | 50 (9%) | 13 (12%) |

| 1 | 364 (20%) | 230 (20%) | 111 (21%) | 23 (21%) |

| 2+ | 1286 (71%) | 835 (71%) | 376 (70%) | 75 (68%) |

| Midlife diabetes | 95 (5%) | 69 (6%) | 22 (4%) | 4 (4%) |

| Midlife hypertension | 646 (36%) | 399 (34%) | 201 (37%) | 46 (41%) |

| Midlife dyslipidemia | 801 (44%) | 493 (42%) | 251 (47%) | 57 (51%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 294 (16%) | 193 (16%) | 88 (16%) | 13 (12%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 180 (10%) | 123 (11%) | 52 (10%) | 5 (5%) |

| Stroke | 96 (5%) | 67 (6%) | 28 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 711 (39%) | 459 (39%) | 212 (39%) | 40 (36%) |

| Cognitive status† | ||||

| Cognitively unimpaired† | 1,564 (86%) | 974 (83%) | 487 (91%) | 103 (93%) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 255 (14%) | 197 (17%) | 50 (9%) | 8 (7%) |

| Anaesthesia exposure in the prior 20 years†,‡ | ||||

| No exposure | 618 (34%) | 446 (38%) | 141 (26%) | 31 (28%) |

| General anesthesia only | 833 (46%) | 529 (45%) | 260 (48%) | 44 (40%) |

| Regional anesthesia only | 118 (6%) | 69 (6%) | 35 (7%) | 14 (13%) |

| Both general and regional anesthesia | 250 (14%) | 127 (11%) | 101 (19%) | 22 (20%) |

Values are n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables. Cognitive status reflects status at the time of first z-score. Regional anesthesia was defined as central neuraxial or peripheral nerve block. Combined general with regional anesthesia was defined as general anesthesia. Cognitive function z-scores are from date of first available global z-score. When not all data is available numbers of rows with complete information are presented.

Indicates a significant univariate association (P<.05) between the characteristic and cause-specific hazard for general anesthesia

Indicates a significant univariate association (P<.05) between the characteristic and cause-specific hazard for regional anesthesia

Abbreviations: APOE = apolipoprotein.

Table 2:

Anesthesia and procedural characteristics prior to censoring*

| Characteristics | Regional Anesthesia (N=137) |

General Anesthesia (N=915) |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia duration, minutes | 146 [108, 179] | 151 [88, 210] |

| Type of Anesthesia | ||

| General | -- | 791 (86%) |

| Combined (general and regional) | -- | 124 (14%) |

| Peripheral nerve block | 72 (53%) | -- |

| Central neuraxial block | 65 (47%) | -- |

| Type of procedure | ||

| General | 5 (4%) | 169 (18%) |

| Orthopedic | 123 (90%) | 231 (25%) |

| Obstetrics/gynecology/urological | 5 (4%) | 126 (14%) |

| Cardiac with bypass | 0 (0%) | 48 (5%) |

| Neurosurgery | 0 (0%) | 50 (5%)† |

| Vascular | 1 (1%) | 33 (4%) |

| Thoracic | 0 (0%) | 24 (3%) |

| Breast/plastic | 0 (0%) | 33 (4%) |

| Otorynolaryngology/oral surgery | 0 (0%) | 58 (6%) |

| Other | 3 (2%) | 142 (16%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Intravenous agents† | ||

| Sodium thiopental | 0 (0%) | 136 (15%) |

| Propofol | 117 (85%) | 774 (85%) |

| Adjuvant opioids | 130 (95%) | 841 (92%) |

| Ketamine | 8 (6%) | 40 (4%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 125 (91%) | 395 (43%) |

| Inhalational agents and nitrous oxide† | ||

| Any volatile anesthetic | NA | 756 (83%) |

| Isoflurane | NA | 392 (43%) |

| Sevoflurane | NA | 172 (19%) |

| Desflurane | NA | 285 (31%) |

| Nitrous oxide | 1 (1%)‡ | 401 (44%) |

Values are n (%) for categorical variables and median [Q1, Q3] for continuous variables. Overall, 648 patients underwent 1,052 procedures prior to censoring (n=341, 113, and 83 patients with 1, 2, and 3 or more general anesthetics respectively and n=89, 18, and 4 patients with 1, 2, and 3 or more regional anesthetics respectively). Combined general with regional anesthesia was classified as general anesthesia. Censoring occurred at the time of last z-score or the time of last z-score prior to occurrence of the patient’s exposure to a second type (regional or general) of anesthesia. Differences between the anesthetic agents used for GA and the type of local anesthetic agents or block location (peripheral vs central) for RA were not assessed in any regression analyses.

Since patients may have received multiple agents, the sum of the number of agents across categories does not equal to the total number of anesthetics.

This patient received N2O via mask due to resolving block by the end of operation.

3.2. Global Cognitive Function after Surgical Exposure

For the global z-score, exposure to surgery with anesthesia after enrollment was associated with an accelerated decline in global cognitive function compared with GA naïve participants (Table 3). This accelerated decline was observed for both RA and GA. For those exposed to RA the estimated difference in annual slope of the global z-score (i.e., the difference from those not exposed to anesthesia) was −0.041 [95%CI −0.072 to −0.010, P=0.011]. For those exposed to GA the estimated difference in slope was −0.061 [95% CI −0.078 to −0.044, P<.001]. The slope of the global z-score was not significantly different for RA and GA (difference was - 0.020, 95%CI −0.053 to 0.014, P=.25; Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3:

Association between post-enrollment regional anesthesia and post-enrollment general anesthesia with cognitive scores over time*

| Regional Anesthesia | General Anesthesia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Slope est‡ |

Difference in slope est. (95% CI) |

P | Difference in slope est. (95% CI) |

P | Regional vs. General P† |

| Primary analysis | ||||||

| Global z score | −0.071 | −0.041 (−0.072 to −0.010) | .011 | −0.061 (−0.078 to −0.044) | <.001 | .252 |

| Memory domain | −0.014 | −0.011 (−0.050 to 0.028) | .565 | −0.065 (−0.084 to −0.045) | <.001 | .011 |

| Language domain | −0.077 | −0.004 (−0.038 to 0.030) | .828 | −0.014 (−0.030 to 0.003) | .099 | .566 |

| Visuospatial domain | −0.041 | −0.013 (−0.045 to 0.020) | .445 | −0.006 (−0.021 to 0.008) | .387 | .709 |

| Attention/executive domain | −0.092 | −0.036 (−0.071 to −0.001) | .044 | −0.052 (−0.072 to −0.033) | <.001 | .394 |

| Sensitivity analysis - orthopedic surgeries only | ||||||

| Global z score | −0.072 | −0.033 (−0.065 to 0.000) | .052 | −0.052 (−0.091 to −0.014) | .008 | .430 |

| Memory domain | −0.014 | −0.011 (−0.052 to 0.031) | .620 | −0.071 (−0.111 to −0.031) | <.001 | .035 |

| Language domain | −0.078 | 0.005 (−0.032 to 0.042) | .784 | 0.000 (−0.035 to 0.034) | .982 | .823 |

| Visuospatial domain | −0.041 | −0.015 (−0.049 to 0.018) | .360 | −0.016 (−0.051 to 0.019) | .366 | .981 |

| Attention/executive domain | −0.091 | −0.030 (−0.067 to 0.007) | .111 | −0.038 (−0.082 to 0.005) | .080 | .756 |

Analyses presented are from adjusted mixed effects models with N=1,813 subjects with complete covariate data. All models are adjusted for prior 20-year exposure to general and regional anesthesia, age, sex, cognitive status at enrollment, education, marital status, Charlson comorbidity index, presence of APOE-ε4 genotype, ever-diagnosed alcohol problem, smoking status, midlife diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and history of atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, stroke, and coronary artery disease. Estimates and confidence limits are for average slope (change in outcome over time) and change in slope after new exposure to regional or general anesthesia. Patients were censored at the date of z-score prior to occurrence of the second type of new anesthesia following first z-score.

P-value for comparison between regional and general anesthesia.

Slope estimate corresponds to the average slope following enrollment prior to a post-enrollment exposure to regional or general anesthesia.

A sensitivity analysis assessed whether exposures in the 20 years prior to MCSA enrollment modify the relationship of RA or GA to global z-scores. There was no evidence of an interaction (P=0.11), suggesting the estimated difference in slope following RA (or GA) versus no exposure was similar for those who were GA naïve i.e. with no exposure in the prior 20 years, and those who had prior exposures before enrollment. Point estimates for the change in slope following RA and change in slope following GA in those with no prior exposure were very similar (−0.042 and −0.059, respectively) to estimates in the overall cohort (Table 3), although confidence intervals were larger considering fewer participants without prior exposures (full data not shown).

Another sensitivity analysis assessed the association between RA, GA alone, and combined GA and RA during a single procedure with subsequent global z-scores. Estimates for all three groups, compared to GA naïve, suggested an accelerated decline following surgery with anesthesia (data not shown), with similar results across the 3 anesthesia exposure types (P=.23).

3.3. Domain-specific Cognitive Scores after Surgical Exposure

In separate analyses, each of the four domain-specific z-scores was assessed separately. Compared to GA naïve, exposure to surgery with RA was associated with accelerated decline in the z-score for the attention/executive function only (difference in slopes of −0.036, 95% CI −0.071 to −0.001; P=.045, Table 3); declines in other domains were not significantly different. In those exposed to surgery with GA, declines in both attention/executive and memory were accelerated (differences in slope of −0.052, 95% CI −0.072 to −0.033, P<.001 and −0.065, 95% CI −0.084 to −0.045, P<.001, respectively, compared to GA naïve). The slopes after exposure to surgery differed between RA and GA only for the memory domain, with a more accelerated decline seen following GA (differential change in slope following GA vs RA was −0.053, 95%CI −0.094 to −0.012, P=.011) (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1).

3.4. Cognitive Trajectories after Orthopedic Procedures

Because the distribution of surgical procedure type was different in those receiving GA vs. RA, a sensitivity analysis was performed that assessed anesthetics given only for orthopedic procedures (n=354). The overall pattern of results was similar to the primary analysis. For those exposed to RA, the estimated difference in the slope of the global z-score (i.e., the difference from GA naïve) was −0.033, 95% CI −0.065 to 0.000 (Table 3). For those exposed to GA the estimated difference in slope was −0.052, 95% CI −0.111 to −0.031. However, the estimated difference in slope for global z-score was not significantly different for RA and GA (P=.43). For domain-specific z-scores, the only statistically significant association between exposure and slopes was in the memory domain for those receiving GA. Comparison of the differences in slopes associated with RA and GA revealed a significant difference only for the memory domain, with a significantly greater difference in slope (i.e., accelerated decline) in those receiving GA.

4. Discussion

The findings of our study did not support the study hypothesis: exposure of older adults to surgery with either RA or GA was associated with a decline in cognitive global-z-score that exceeded that experienced by MCSA participants who did not undergo surgery with anesthesia. The slope of this decline did not significantly differ between patients receiving surgery with RA and GA. However, analysis of domain-specific cognitive z-scores provided some evidence that participants receiving GA experienced greater declines in memory compared to those receiving RA. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether our finding of memory preservation after RA may benefit older adults undergoing selective procedures.

Two systematic reviews have compared the effects of RA and GA on short-term (<6 months) postoperative cognition [15, 16]. The first [16] analyzed 17 studies, reported that a significant proportion of patients, especially the elderly, exhibited cognitive dysfunction in the immediate postoperative period. However, there was little evidence suggesting that cognitive dysfunction persists beyond 6 months or that the incidence differed between patients receiving RA and GA. The second [15] found that of 16 studies examining cognitive outcomes, 2 favored GA [34, 35] and 1 RA [36], whereas the remaining 13 showed little difference between GA and RA on short-term postoperative cognitive function. Only two studies have examined long-term cognitive outcomes following GA or RA. A retrospective cohort analysis found that exposure of patients, 50 years of age or older, to either GA or RA was associated with risk of subsequent dementia [4]. In another study, patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy were randomized to receive sevoflurane, propofol, or epidural anesthesia [17]. The risk of AD at 2 years postoperatively did not depend upon anesthetic type, but MCI was more common in the sevoflurane group [17].

A prior analysis of this MCSA cohort utilized a methodology similar to that employed in the present analysis to determine the association between exposure to GA and postoperative cognitive trajectories [18]. Exposure conditions included GA in the 20 years prior to MCSA enrollment, and exposures after enrollment only among those not exposed to GA within 20 years prior to enrollment. Both exposure conditions were associated with accelerated decline in global z-score (differences in slope of −0.018 and −0.041, respectively). The current analysis now also includes those receiving RA as a primary technique, but did not separately analyze those who did and did not have exposure prior to MCSA enrollment, rather including prior exposure as a covariate. However, sensitivity analysis suggests that this approach has little effect on the pattern of results. As expected [18], the current analysis confirms that exposure to GA and surgery is associated with accelerated decline in global cognitive function. The new finding that slopes of global z-scores did not differ between participants who were exposed to surgery with GA or RA suggests that the accelerated cognitive decline after GA may be related to factors not related to the anesthetic drugs, such as the condition necessitating surgery, comorbidities, surgical stress, and others. Thus, the need for anesthesia may serve as a marker for other factors causing cognitive decline. As we noted in our prior work [18], the magnitude of the difference in cognitive trajectories associated with anesthesia exposure is small and of uncertain clinical significance.

Even though there was little evidence of differential associations between anesthetic technique and global cognitive function, our analyses provided some evidence for differential associations for cognitive-specific domains that comprise the global z-score. Visuospatial and language skills are well-preserved with aging [37–40], and there is little evidence that their trajectories were associated with exposure to surgery and anesthesia. Normal cognitive aging, as well as AD, is most frequently associated with declines in memory and executive functions [38, 39]. Changes in the trajectories of these domains were associated with exposure to surgery and anesthesia. Although changes in the slope of attention/executive function were similar among GA and RA, accelerated decline in memory was observed only in participants undergoing GA, but not RA. A similar pattern was observed in the sensitivity analysis including only orthopedic procedures. Thus, we cannot exclude the potential for an association of GA with accelerated declines in memory, and this observation will require further confirmation.

This and other similar observational studies have several well-recognized limitations. The most important is the potential for confounding by indication: factors leading to the choice of RA could be related to the outcome. This choice may be influenced by the acuity of coexisting disease (e.g., a more debilitated patient may not be considered suited for certain type of anesthesia), complexity of surgery (e.g., bilateral hip procedures requiring GA), or preference of surgeon or patient [41]. Indeed, there is evidence of significant variability in anesthetic care for orthopedic procedures based on demographic (gender, race, socioeconomic status) and other factors [42]. Furthermore, the proportion of patients receiving RA differed according to type of surgery, which could represent a significant confounding factor if postoperative cognitive function depends on surgery type. Indeed, we included neurosurgical cardiopulmonary bypass cases and major vascular operations, which could cause changes in cognition. However, the finding that a similar pattern of results was observed in a sensitivity analysis including only orthopedic surgeries argues against differences in types of surgery being the explanation for our overall findings. As previously discussed [18], other unmeasured confounding variables are possible, including time-dependent factors which may be associated with cognitive decline and need for surgical procedures. Also, the MCSA is a prospective study with information of cognitive scores collected in planned 15-month time intervals. Given that it was not designed specifically to support the current analysis, the timing of the MCSA visits did not correspond to any consistent time interval surrounding exposures to surgery with anesthesia which were retrospectively ascertained from the medical records. However, our analyses are still able to evaluate changes in cognitive function before and after exposure. Therefore, the prospective nature of the cohort was not compromised by the way in which the exposures were ascertained. Finally, most patients receiving RA were also administered agents such as propofol for sedation, and these agents are also utilized during GA. Although during RA these agents are administered in lower doses than those used to achieve GA, this factor could contribute to cognitive decline if anesthetic drugs are causative of cognitive decline. Of note, propofol administered in GA doses was not associated with cognitive deterioration in patients with MCI [17].

5. Conclusion

Exposure of older adults to RA is associated with an increase in the rate of cognitive decline in global cognition when compared with adults not exposed to any anesthesia. Further the rate of decline associated with RA is similar to rate of decline associated with GA. This finding argues against a causative role for GA agents in producing long-term postoperative declines in global cognition. Secondary analysis suggested that patients receiving GA may experience greater declines in memory compared to patients receiving RA, but this finding would require further confirmation before any inferences regarding mechanism or changes in practice could be supported.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

1. Systematic review: PubMed was searched for titles describing role of surgery with regional anesthesia (RA) on cognitive function. While several studies have examined the association between surgery with general anesthesia (GA) and cognitive function, less evidence exists regarding the effect of surgery with RA on long-term cognitive outcomes. 2. Interpretation: This longitudinal population-based study suggests that exposure of older adults to surgery with RA or GA was associated with a decline in global cognitive z-score that exceeded that observed in those with no such exposure. The decline in slope did not differ between patients who underwent surgery with RA versus GA. Analysis of secondary endpoints showed that patients receiving GA experienced greater declines in memory compared to patients receiving RA. 3. Future directions: In order to elucidate potentially modifiable risk factors, future research should focus on the causation between exposure to surgery with GA or RA and cognition.

Highlights:

Exposure to surgery with anesthesia is associated with accelerated global cognitive decline

After exposure to surgery with anesthesia cognition decline exceeds that seen in unexposed participants

The decline in global cognitive function is similar after regional and general anesthesia

Accelerated decline in memory may occur after surgery with general but not regional anesthesia

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Mr. Jeremiah Aakre, statistician for the MCSA. This study was supported by the NIH grants P50 AG016574 and U01 AG006786 (Petersen), by the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program, the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 AG034676, Principal Investigators: Walter A. Rocca, MD, and Jennifer St. Sauver, PhD) and the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Sciences Activities (CTSA), grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Financial support for statistical analyses was provided by the Department of Anesthesiology Mayo Clinic.

Disclosures: D.S.K. previously served as deputy editor for the journal Neurology, and he serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck and for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trials Unit. He is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, Eli Lilly and Co, and TauRx Therapeutics Limited and receives research support from the NIH. M.M.M. has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and has received unrestricted research grants from Biogen and Lundbeck. R.C.P. is the chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Pfizer Inc and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, LLC, and has served as a consultant for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; Merck and Co, Inc; and Genentech Inc. He receives royalties from sales of the book Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press). J.S., T.N.W., P.J.S., A.C.H., D.P.M., D.R.S., and D.O.W. have nothing to disclose.

Alphabetical List of Abbreviations:

- APOE ε4 allele

apolipoprotein E genotype

- GA

general anesthesia

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MCSA

Mayo Clinic Study of Aging

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

- RA

regional anesthesia

Footnotes

We, the authors, declare that we have no competing interests.

Note: J.S. and D.R.S. have full access to all the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. They also have final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xie Z, Culley DJ, Dong Y, Zhang G, Zhang B, Moir RD, et al. The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces caspase activation and increases amyloid beta-protein level in vivo. Ann Neurol 2008; 64:618–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Z, Tanzi RE. Alzheimer’s disease and post-operative cognitive dysfunction. Exp Gerontol 2006; 41:346–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckenhoff RG, Johansson JS, Wei H, Carnini A, Kang B, Wei W, et al. Inhaled anesthetic enhancement of amyloid-beta oligomerization and cytotoxicity. Anesthesiology 2004; 101:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen PL, Yang CW, Tseng YK, Sun WZ, Wang JL, Wang SJ, et al. Risk of dementia after anaesthesia and surgery. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204:188–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schenning KJ, Murchison CF, Mattek NC, Silbert LC, Kaye JA, Quinn JF. Surgery is associated with ventricular enlargement as well as cognitive and functional decline. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 12:590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprung J, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Olive DM, Gappa JL, Sifuentes VL, et al. Association of mild cognitive impairment with exposure to general anesthesia for surgical and nonsurgical procedures: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91:208–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprung J, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Price LL, Schulz HP, Tatsuyama CL, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and exposure to general anesthesia for surgeries and procedures: a population-based case-control study. Anesth Analg 2017; 124:1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sprung J, Jankowski CJ, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, Aguilar AL, Runkle KJ, et al. Anesthesia and incident dementia: a population-based, nested, case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88:552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dokkedal U, Hansen TG, Rasmussen LS, Mengel-From J, Christensen K. Cognitive functioning after surgery in middle-aged and elderly Danish twins. Anesthesiology 2016; 124:312–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes CG, Patel MB, Jackson JC, Girard TD, Geevarghese SK, Norman BC, et al. Surgery and anesthesia exposure is not a risk factor for cognitive impairment after major noncardiac surgery and critical illness. Ann Surg 2017; 265:1126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel D, Lunn AD, Smith AD, Lehmann DJ, Dorrington KL: Cognitive decline in the elderly after surgery and anaesthesia: results from the Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA) cohort. Anaesthesia 2016; 71:1144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulte PJ, Martin DP, Deljou A, Sabov M, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Effect of Cognitive Status on the receipt of procedures requiring anesthesia and critical care admissions in older adults. Mayo Clin Proc 2018; 93:1552–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002; 183:630–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahnenkamp K, Herroeder S, Hollmann MW. Regional anaesthesia, local anaesthetics and the surgical stress response. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2004; 18:509–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis N, Lee M, Lin AY, Lynch L, Monteleone M, Falzon L, et al. Postoperative cognitive function following general versus regional anesthesia: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2014; 26:369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman S, Stygall J, Hirani S, Shaefi S, Maze M. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. Anesthesiology 2007; 106:572–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Pan N, Ma Y, Zhang S, Guo W, Li H, Zhou J, Liu G, et al. Inhaled sevoflurane may promote progression of amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a prospective, randomized parallel-group study. Am J Med Sci 2013; 345:355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulte PJ, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Hanson AC, Schroeder DR, et al. Association between exposure to anaesthesia and surgery and long-term cognitive trajectories in older adults: report from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Br J Anaesth 2018; 121:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology 2008; 30:58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: Half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87:1202–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Pankratz JJ, Brue SM, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 2012; 41:1614–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vemuri P, Knopman DS, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Mielke MM, Graff-Radford J, et al. Evaluation of amyloid protective factors and Alzheimer disease neurodegeneration protective factors in elderly individuals. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74:718–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokmen E, Smith GE, Petersen RC, Tangalos E, Ivnik RC. The short test of mental status. Correlations with standardized psychometric testing. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:725–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hachinski VC, Iliff LD, Zilhka E, Du Boulay GH, McAllister VL, Marshall J, et al. Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Arch Neurol 1975; 32:632–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen WG, Terry RD, Fuld PA, Katzman R, Peck A. Pathological verification of ischemic score in differentiation of dementias. Ann Neurol 1980; 7:486–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahn S, Elton RL, Committee UD. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale In: Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease Volume 2, edn. Edited by Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, Goldstein M: Florham Park: MacMillan Healthcare Information; 1987; 153–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler DA: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reitan RM: Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Motor Skills 1958; 8:271–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S: The Boston Naming Test, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Bohac DL, Tangalos EG, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies: category fluency norms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1998; 20: 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler DA: Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE: WAISR, WMS-R and AVLT norms for ages 56 through 97. Clin Neuropsychol 1992; 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Machulda M, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Association of lifetime intellectual enrichment with cognitive decline in the older population. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71:1017–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones MJ, Piggott SE, Vaughan RS, Bayer AJ, Newcombe RG, Twining TC, et al. Cognitive and functional competence after anaesthesia in patients aged over 60: controlled trial of general and regional anaesthesia for elective hip or knee replacement. Brit Med J 1990; 300 (6741):1683–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karhunen U, Jonn G: A comparison of memory function following local and general anaesthesia for extraction of senile cataract. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1982; 26:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandal S, Basu M, Kirtania J, Sarbapalli D, Pal R, Kar S, et al. Impact of general versus epidural anesthesia on early post-operative cognitive dysfunction following hip and knee surgery. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2011; 4:23–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwood PM, Parasuraman R, Haxby JV. Changes in visuospatial attention over the adult lifespan. Neuropsychologia 1993: 31:471–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel KL. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med 2013: 29:737–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayden KM, Welsh-Bohmer KA. Epidemiology of cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease: contributions of the cache county utah study of memory, health and aging. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2012; 10:3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, Glymour MM, Elbaz A, Berr C, Ebmeier KP, et al. Timing of onset of cognitive decline: results from Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Brit Med J 2012; 344:d7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salam AA, Afshan G. Patient refusal for regional anesthesia in elderly orthopedic population: A cross-sectional survey at a tertiary care hospital. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016; 32:94–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cozowicz C, Poeran J, Memtsoudis SG. Epidemiology, trends, and disparities in regional anaesthesia for orthopaedic surgery. Br J Anaesth 2015: 115 Suppl 2:ii57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.