Abstract

Falls are a significant issue for older adults, and many older adults who once received care in nursing homes now reside in assisted living communities (ALCs). ALC staff needs to address resident falls prevention; however, federal or state requirements or oversight are limited. This research explores falls prevention in Wisconsin ALCs in the context of the Kotter Change Model to identify strategies and inform efforts to establish a more consistent, proactive falls prevention process for ALCs. A mixed methods approach demonstrated inconsistency and variability in the use of falls risk assessments and prevention programs, which led to the development of standardized, proactive falls prevention process flowcharts. This process, as delineated, provides ALCs with an approach to organize a comprehensive falls reduction strategy. Findings highlight the importance of educating staff regarding assessments, resident motivation, falls prevention programs and feedback, all key components of the falls prevention process.

INTRODUCTION

The older adult population (age 65+) in the United States is projected to increase by 30 million in the next 20 years (Czaja & Sharit, 2009; Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014) and double by 2060 (Colby & Ortman, 2015; Mather, Jacobsen, & Pollard, 2015). As baby boomers age, the burden of disease and medical costs is expected to rise sharply. Falls are one of the most significant health issues facing older adults. It is estimated that 30 to 40% of older adults will fall at least once this year (Ambrose, Paul, & Hausdorff, 2013). In 2015, falls in older adults in the United States resulted in 3 million emergency room visits with 28% requiring in a hospital stay at a total cost of approximately $43 billion (CDC, 2017). By 2030, healthcare expenditures resulting from falls in older adults could reach $100 billion (Houry, Florence, Baldwin, Stevens, & McClure, 2016).

The picture in Wisconsin is very similar. The older adult population is projected to increase by 41% in the next 10 years and by 2040, an additional 640,000 Wisconsinites are predicted to be over age 65, a 72% increase from 2015 (Egan-Robertson, 2013). A recent analysis found that Wisconsin, compared to other states, had the 3rd highest older adult falls mortality rate (90.3 per 100,000 persons). (Alamgir, Muazzam, & Nasrullah, 2012) In 2014, falls in older Wisconsin residents resulted in approximately 17,000 hospitalizations and 37,000 falls-related emergency department (ED) visits (WIDHS, 21 Jul 2016). At an average cost of almost $35,000 per hospital stay and $3,100 per ED visit (WIDHS, 21 Jul 2016), over $715 million was spent in Wisconsin hospitals for fall related injuries.

The past 20 years have seen a dramatic shift in residential long term care, as medically frail older adults with complex health conditions or individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities who previously received care in nursing homes and hospitals are now residing in Assisted Living Communities (ALCs). In 2003, Wisconsin had 43,052 nursing home resident beds compared to 30,411 Assisted Living resident beds. By 2015, nursing home resident beds decreased by approximately 8,600 (total = 34,463 beds) versus an increase in Assisted Living resident beds of 23,972 (total=54,383 beds) (Johnson, 2016). As the ALC resident population increases so does the need to provide, ensure, and improve quality in these communities.

Studies suggest that approximately 30% of older adults residing in ALCs had one or more falls in the past 90 days (McGough, Logsdon, Kelly, & Teri, 2013; Stock, Amuah, Lapane, Hogan, & Maxwell, 2017). Unlike nursing homes, ALCs have few federal or state requirements and limited oversight for quality improvement, including efforts to address resident falls prevention. While little federal regulation regarding falls prevention in ALCs exists, the Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG 09.02.01) for Home Care and Long Term Care outlines components that long-term care facilities seeking accreditation must implement to reduce the risk of falls (TJC, 2016a, 2016b). However, ALCs do not commonly seek Joint Commission accreditation. The state of Wisconsin licensing regulations for ALCs focus on resident rights to a safe environment, but not specifically to falls prevention (WIDHS).

Similar to nursing homes, ALCs offer a range of services, from home-like settings with minimal care to multiple skilled services. Falls prevention is one such service. However, ALCs lack specific guidance on what type of falls prevention programs to implement. The American Geriatric Society/British Geriatric Society (AGS/BGS) developed comprehensive guidelines related to falls risk assessment and specific falls prevention interventions for community dwelling older adults (AGS, 2011). However, guideline use and implementation approaches have not been studied in the ALC environment. This study addresses these issues by exploring the components of the falls prevention processes utilized in Wisconsin ALCs, to help create a standardized, proactive approach to address the falls prevention process in ALCs.

The falls prevention process and flowchart were evaluated within the context of Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model to determine if the process developed supports implementation of a change in the approach to falls prevention in ALCs (Kotter, 1995). Kotter’s steps include: 1) increased urgency; 2) building guiding teams; 3) getting the vision right; 4) communication for buy in; 5) enabling action; 6) creating short-term wins; 7) don’t let up; and 8) making it stick. The first three steps create a climate for change within an organization. The second three steps provide structure for engaging and enabling an organization. The final two steps encourage a process for implementing and sustaining change. To date, research in the applicability of Kotter’s change model to the implementation of falls prevention in long-term care is limited (Frieson, Foote, Frith, & Wagner III, 2012).

METHODS

Study Setting

Wisconsin is a leader in recognizing the importance of addressing and improving quality in assisted living. In 2009, a public–private coalition, the Wisconsin Coalition for Collaborative Excellence in Assisted Living (WCCEAL) was established, bringing together a group of stakeholders who sought to improve outcomes for residents of Wisconsin ALCs (https://wcceal.chsra.wisc.edu/). The Coalition consists of the four Wisconsin assisted living associations, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (with representation from both the regulatory body and the LTC Medicaid body), the consumer advocates, long term care insurance providers and the University of Wisconsin – Center for Health Systems Research and Analysis (CHSRA). Since 2013, the Coalition has created and implemented an online resource and infrastructure designed to improve the quality provided by participating ALCs. At the end of 2015, 11% (n = 400) of the 3,700 ALCs in Wisconsin were active Coalition members representing 26% (n = 12,839) of the 50,088 state licensed assisted living beds.

Data Sources and Analysis Approach

A mixed methods approach including a voluntary falls prevention questionnaire and a structured interview was utilized to collect data about falls and falls prevention in Coalition ALCs. Falls and falls with injury as defined on the Coalition website are:

Fall: an event which results in a person coming to rest on the ground or other lower level precipitated by a misstep such as a slip, trip, or stumble; or as a consequence of loss of consciousness or complication from a medical condition; loss of grip or balance; from jumping; or from being pushed, bumped, or moved by another person, animal or inanimate object or force.

Fall with injury: a fall that results in an injury requiring medical treatment such as a wound, a fracture, a head injury such as a concussion or hematoma, a serious sprain or ligament damage causing decreased mobility or function, or other damage to the body.

Falls Prevention Questionnaire

The 13-item voluntary falls prevention questionnaire (available upon request) investigated the processes ALCs use to track falls and develop falls prevention strategies. The questionnaire asked about: (a) processes to measure and track falls, (b) dissemination of falls information in the ALC, and (c) approaches utilized to mitigate falls risk and investigate falls. It also asked about the falls prevention program utilized, presence of multiple fallers, and allowed ALCs to provide additional information about falls and falls prevention. This questionnaire was distributed through the Coalition website in April 2015. Coalition ALC members were invited, but not required to respond. The analysis included descriptive statistics of the structured quantitative questions. The research team developed a coding scheme to independently review the open-ended question responses. Results were compared for consistency and differences reconciled.

Falls Prevention Structured Interview Guide

Findings from the above optional falls prevention questionnaire informed the development of the structured qualitative interview guide (available upon request). The detailed interview guide allowed the research team to gain a deeper understanding of the falls prevention process within an ALC. The guide included questions about falls risk assessment, the falls prevention program utilized and if it differed for residents with cognitive impairment, and data monitoring and dissemination approaches related to falls and falls prevention within the ALC. Questions about ALC characteristics (e.g., licensed beds, resident demographics) were also included in the interview guide. The ALC interview pool was selected to address the diversity of falls prevention programs utilized by Coalition ALC members. The goal was to interview six ALCs from each of the four assisted living associations. Specifically, the objective was to interview two ALCs who self-reported using an association-developed falls prevention program, two who did not have a falls prevention program; and two ALCs using another falls prevention program not developed by their member association (e.g., Stepping On). The 2015 second quarter Coalition data was used to identify ALCs meeting these criteria and extract organizational characteristics (ALC care type, primary population served and falls prevention program) The ALC staff who agreed to participate, partook in a one-hour telephone interview, conducted by at least two members of the research team. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Research team members developed and used a coding scheme to independently review the interviews. Results were compared for consistency and differences were reconciled by the research team.

Flowchart Development

The results from the questionnaires and interviews revealed inconsistency and variability in the use of falls risk assessments and prevention programs by ALCs. (Table 1 and Table 2) The falls prevention questionnaires and interview responses, including the open-ended questions were reviewed, analyzed, and utilized to develop the initial falls prevention process flowcharts. These flowcharts were distributed to the ALC interview participants and coalition members to assess validity. Feedback received was used to modify and further validate the ALC falls prevention process flowcharts presented in this manuscript.

Table 1 –

Wisconsin Coalition for Collaborative Excellence in Assisted Living (WCCEAL): A Comparison of the Interview Sample versus all non-interviewed WCCEAL members (2nd Quarter 2015)

| Non-Interviewed WCCEAL ALCs | Interviewed WCCEAL ALCs | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | 362 | 23 |

| Care Type | % (N) | % (N) |

| Adult Family Home (AFH) | 8.3% (30) | 13.0% (3) |

| Community Based Rehabilitation Facilities (CBRF) | 63.5% (230) | 65.2% (15) |

| Residential Care Apartment Complex (RCAC) | 28.2% (102) | 21.7% (5) |

| Primary Population (Sort by % and Highlight) | ||

| Advanced Age | 56.1% (203) | 60.9% (14) |

| Correctional Clients | 0.8% (3) | N/A |

| Developmentally Disabled | 8.3% (30) | 21.7% (5) |

| Emotionally Disturbed/Mental Illness | 5.5% (20) | N/A |

| Irreversible Dementia/Alzheimer’s | 17.7% (64) | 13.0% (3) |

| Physically Disabled | 0.8% (3) | N/A |

| Terminally III | 0.3% (1) | N/A |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 1.1% (4) | 4.3% (1) |

| Veterans Administration | 0.6% (2) | N/A |

| Not Available | 8.8% (32) | N/A |

| Primary Falls Prevention Program | ||

| No primary falls prevention program identified | 55.0% (199) | 26.1% (6) |

| Assisted Living Association Sponsored program | 14.9% (54) | 47.8% (11) |

| Not applicable due to community population | 0.8% (3) | 0.0% (0) |

| Other (e.g., CDC STEADI, Stepping On) | 14.9% (56) | 13.0% (3) |

| Information Not Available | 14.4% (52) | 13.0% (3) |

Data for the non-interviewed coalition members was extracted from the 2nd Quarter 2015 Coalition reports.

Table 2:

Components of Falls Risk Assessments in Assisted Living Communities

| Falls Risk Assessment Component | # of ALCs (n=13) | % of ALCs |

|---|---|---|

| Medications | 12 | 92% |

| Gait/Balance Ambulation/Equipment | 11 | 85% |

| History of Falls | 10 | 77% |

| Predisposing Disease/condition | 10 | 77% |

| Mental Status/cognition | 9 | 69% |

| Blood Pressure | 8 | 62% |

| Vision/Sensory Status | 6 | 46% |

| Continence-(Activities of Daily Living) | 5 | 39% |

| Impulsive behaviors | 2 | 15% |

The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study (#2015–0812).

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

Falls Prevention Questionnaire

A total of 92 active Coalition members (26%) responded to the falls prevention questionnaire. At the request of the assisted living associations, the optional falls prevention questionnaire did not include any ALC characteristics (e.g., bed size). As such, questionnaire respondent demographics could not be assessed.

Falls Prevention Interviews

The ALC interview included respondent characteristic questions. Wisconsin licensed residential ALCs are divided into three care types: Adult Family Homes (AFHs), Community Based Residential Facilities (CBRFs), and Residential Care Apartment Complexes (RCACs) (WIDHS, 12 Aug 2016). Approximately 50% of licensed ALCs are AFHs, 41% are CBRFs, and 9% are RCACs. Thirteen ALC staff representing stand-alone and corporate ALCs (n=23), participated in the interviews. Table 1 compares ALC characteristics by care type and primary population in the interview sample (n=23) to all other Coalition members (n=362).

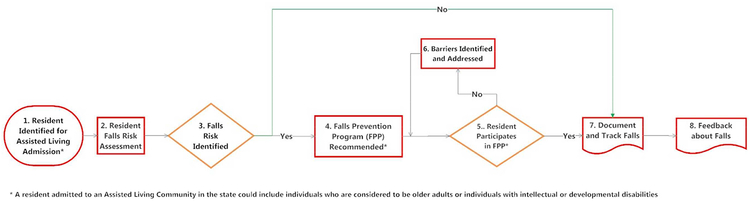

The ALC Falls Prevention Process Flowchart (Figure 1) outlines the key components of a proactive falls prevention process in an ALC. Upon admission (Box 1), a resident undergoes a falls risk assessment (Box 2). If appropriate (Box 3), a falls prevention program (Box 4) is then chosen based on available resources. The resident with a falls risk is encouraged to participate in the falls prevention program (Box 5), although resident non-participation is a choice. If the resident declines participation, barriers to participation are identified and addressed (Box 6), and the resident is again encouraged to participate in a falls prevention program (Box 5). Boxes 7 and 8 focus on documentation and communication and are discussed later in the manuscript.

Figure 1 – ALC Fall Prevention Process Flowchart.

* A resident admitted to an Assisted Living Community in the state could include individuals who are considered to be older adults or individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities

Initial Falls Risk Assessment

The initial falls risk assessments, which occurs after a resident is admitted to the ALC, varied widely, as reported by the ALCs interviewed. Approximately half of the interviewees reported asking about falls during the initial general intake assessment. Of these, four relied on either a “home grown” or corporate falls assessment, and three utilized a more standardized falls risk assessment (e.g., Medline, Briggs, or Heinrich). Two interviewees reported not having either a general or specific initial falls assessment. Components within the falls risk assessment varied by ALC interviewed (Table 2). ALCs interviewed addressed some elements of the AGS/BGS recommendations for a comprehensive falls risk assessment (AGS, 2011). 75% of the ALCs interviewed asked about medications, resident gait, balance, and use of assistive equipment, falls history, and predisposing disease (e.g., diabetes). Four ALCs reported having a secondary process for reassessing falls risk for their residents. Efforts included: (a) scheduling falls risk reassessments every six months on all residents in their CBRFs (n=2); (b) conducting yearly falls risk reassessments for residents living in their RCAC (n=1); or (c) reassessing falls risk whenever a change of medical condition was noted in their residents (n=1).

Implementation of Falls Prevention Program

If a falls risk is identified (Box 3), the ALC falls prevention program (Box 4), is recommended to the resident. The type of falls prevention program utilized in both the interviewed sample and non-interviewed Coalition ALCs varied (Table 1). In the interview sample, 26.1% of the ALCs (n=6) indicated that they did not have a falls prevention program. By comparison, 55% of active Coalition members in the second quarter of 2015 reported not having a falls prevention program. Approximately 14% of ALCs in both groups did not provide information about their falls prevention program. 60.8% of the ALCs interviewed used an association sponsored falls prevention program (n=11) or a similar program such as Stepping On or CDC Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) (n=3) as compared to 29.8% (n=110) of the coalition sample. Our analysis determined that four interviewed ALCs had a ‘reactive’ falls prevention program, meaning that they do not actively seek to prevent falls based on the resident’s falls risk assessment, instead waiting until a fall occurs to make changes. One ALC stated: “It’s a homegrown operation based on the assessments that all of our RNs are doing in all of the other communities and trying to basically … [determine]… why is this happening? How can we prevent it? And what kind of operations can we put in place to be preventative instead of reactive?” (ALC9)

Barriers to Adopting a Fall Prevention Program

If a resident chooses not to participate in the ALC falls prevention program (Box 5), organizational or resident level barriers may exist that inhibit participation (Box 6). When addressing barriers to adopting a falls prevention program, two ALCs acknowledged not seeing a need for a program or not seeing falls prevention as a priority in their ALC. Other ALCs (n=3) reported not having a clear vision regarding falls prevention strategies. Others relied on their corporation or association to provide access to available resources. One ALC stated, “Well I think our corporate office is taking care of it so we will use whatever falls prevention that they give us.” (ALC8) Three ALCs reported difficulty finding information regarding falls prevention or that the available information was overwhelming, and that they were unsure how to implement a program. Two ALCs cited staffing issues (e.g., too busy or not enough time, CNAs having difficulty mastering root cause analysis) as a barrier to adopting a falls prevention program.

Two interviewees identified resident motivation as a barrier to falls prevention program engagement. One interviewee indicated that “[residents] that could benefit the most are the least likely to actually participate in an activity” (ALC12). The other ALC offers an annual falls clinic which provides opportunities for residents to work with a physical therapist. Despite efforts to “make it fun, of course, feed them because it’s a good way to get them [residents] down here”, the residents do not want to participate. However, the staff stated, “… But they [residents] don’t always want to participate in things. They kind of want to be left alone It’s …getting the tenants interested in it would be the hardest part.” (ALC11)

Post Fall Assessments/Root Cause Analysis

When a fall occurs, ALC staff then focuses on the process steps outlined in Boxes F1 to F4 (see Figure 2). If a resident falls (Box F1), ALC staff conducts a post-fall assessment that may include a root cause analysis (Box F2). Upon completion, a plan is initiated to prevent future falls (Box F3), and clinical documentation occurs which may include updating the Individual Service Plan (ISP)/Care plan as well as communication to staff, family, and/or primary care providers about the plan (Box F4). After the fall, documentation and tracking of the fall occurs (Box 5) and the ALC returns to the linear, proactive, and preventative section of the process addressed above (Box 2) until the next fall occurs.

Figure 2 – ALC Falls Prevention Process Flowchart when a Resident Falls.

* A resident admitted to an Assisted Living Community in the state could include individuals who are considered to be older adults or individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities

^ Process steps may not be present in all Assisted Living Communities.

All individuals interviewed reported having some post-fall follow up in their ALC. Ten (77%) used either a self-identified or implied root cause analysis. Root cause analysis is a tool to help identify what, how, and why an event occurred so that steps can be taken to prevent future occurrences (Rooney & Heuvel, 2004). One respondent stated, “Every fall initiates an investigation which really is more of a root cause analysis than anything else. So person A had a fall, what are the whys of that fall? Why did that person fall? Well, they didn’t have their shoes on, so why didn’t they have their shoes on?” (ALC10) Other respondents utilized varying approaches to conduct a post fall assessment. Four ALCs referred a resident to physical therapy for further assessment. While three ALCs repeated their pre-falls assessment, other ALCs utilized a more formal assessment (e.g., Briggs, Modified Morse) or changed staff rounding frequency.

Documentation, Communication, and Tracking

In the falls prevention process, the ALCs track the occurrence of falls and document the nature of and reason for the fall (Box 7). The ALC may receive feedback about efforts to prevent falls (Box 8). At this point, two feedback loops occur: resident specific and ALC specific; resident specific feedback may promote individual fall prevention. ALC specific feedback involves documentation and reporting of the fall and the potential receipt of corporate or association feedback about efforts to prevent falls. The falls prevention questionnaire results showed that once a fall occurs, not all of the ALCs reported having a consistent process to document or track and review information about the fall (see Table 3).

Table 3:

Assisted Living Community Reported Falls Prevention Program and Falls Outcomes1

| What type of Falls are Tracked in the Community | |

| 1. All Falls (including falls with injuries) | 82 (88.2%) |

| 2. Only Falls with Injury | 3 (3.2%) |

| 3. We do not track falls in our community | 0 (0.0%) |

| 4. Not Applicable/Skipped Question | 8 (8.6%) |

| How often does the Community track and review information about falls without injury across all residents? | |

| 1. Track daily and review monthly | 37 (39.8%) |

| 2. Track and review monthly | 22 (23.7%) |

| 3. Track monthly but review quarterly | 9 (9.7%) |

| 4. Track and review quarterly | 6 (6.5%) |

| 5. Not Applicable/Skipped Question | 8 (8.6%) |

| 6. As they occur | 5 (5.4%) |

| 7. Other responses (e.g., bi-annual, safety meeting, bi-weekly, change of condition | 6 (6.5%) |

| How often does the Community track and review information about falls with injury across all residents? | |

| 1. Track daily and review monthly | 44 (47.4%) |

| 2. Track and review monthly | 18 (19.4%) |

| 3. Track monthly but review quarterly | 7 (7.5%) |

| 4. Track and review quarterly | 4 (4.3%) |

| 5. As they occur | 9 (9.7%) |

| 6. Not Applicable/Skipped Question | 8 (8.6%) |

| 7. Other responses (e.g., bi-annual, bi-weekly, if falls occurs, review weekly) | 3 (3.2%) |

Total sample size is 93 Assisted Living Communities. Data was collected in April 2015.

The questionnaire asked ALCs to identify the process utilized to report or track falls (Table 4). A majority (62%) of respondents indicate that their process focuses on resident-specific reporting. While we might expect that each ALC has a system in place to track falls, only 32 ALCs (34%) reported using some type of falls database, report, or spreadsheet to track falls, and only 31% (n=29) of the ALCs identified an individual who is responsible for tracking and reporting on falls in their ALC.

Table 4:

Processes Utilized in Assisted Living Communities to Report and Track Falls1

| N (% of Total) | |

|---|---|

| A. Process | |

| 1. Resident specific reporting | 58 (62.4%) |

| 2. Community falls database, report or spreadsheet | 32 (34.4%) |

| 3. Staff verbal communication (e.g., via huddle, discussion or other indication of a verbal exchange) | 7 (7.5%) |

| 4. Follow-up intervention | 48 (51.6%) |

| 5. Indication that the ALC policy and procedures is followed including QI/QA | 8 (8.6%) |

| 6. Incident communicated with a physician or Family or other individuals | 6 (6.5%) |

| 7. Other (e.g. Root Cause Analysis, Review of Prior Falls) | 7 (7.5%) |

| B. Staff implementing the process to track and report falls (e.g. Nurse Manager) | 29 (31.2%) |

Total sample size is 93 Assisted Living Communities. Data was collected in April 2015

Of the ALCs interviewed, 23% (n=3) indicated that they share the information about falls with their corporate office and may receive specific feedback on how to improve their falls process. One ALC stated, “It is tracked on a spreadsheet which goes to our corporate which does the comparison across all of the communities … Some of that information has been used to help determine the layout of the new communities”. (ALC 9)

Efforts to document and track falls focus on communication about the number of falls within an ALC. However, communication also occurs when a falls risk is identified and after a fall occurs. In these situations, the focus is on sharing information with staff, the resident’s family, or primary care provider. When asked about an internal process to communicate with these individuals, only 39% (n=36) of ALCs responding to the falls prevention questionnaire have a process to communicate a falls risk, as compared to only 19% (n=18) with a process to communicate an incident of a fall.

DISCUSSION

This study explored how assisted living communities (ALCs) address an important public health issue – falls in older adults. Our results confirmed that many Wisconsin ALCs lack structure and consistency in their approaches to mitigate and address resident falls. The intent is that the derived falls prevention process flow charts would be utilized to assist ALCs, currently with or without a falls prevention program, to understand and implement a proactive and comprehensive falls prevention process.

Existing national and Wisconsin state data creates an urgency to adopt a comprehensive falls prevention processes in ALCs given the number of falls, and the health care expenditures related to falls (Kotter’s first step). Based on Kotter’s change model, the change theory falls model examined how a sense of urgency changed staff behaviors in a single long-term care setting (Frieson et al., 2012). Given that a significant number of Wisconsin ALCs have not adopted a falls prevention program, our falls prevention process flowchart may support similar changes in behavior.

While the requirement for falls risk assessment is not consistent across all Wisconsin ALC regulations, it is recommended that such an assessment take place on admission and when there is a change of health condition. However, Wisconsin Administrative Code lacks specificity and guidance to ALCs on how to conduct the assessment (WIBAL, 2015). The risk assessment is one key factor in falls prevention in ALCs and is most effective when combined with a falls prevention program and appropriate follow up (Kenny et al., 2011). Additionally, the falls risk assessment as outlined in the falls prevention process serves as a method to identify an individual’s fall risk, thereby creating urgency for developing a falls prevention process to decrease the incidence of falls for a given individual.

The overall falls prevention process delineated in this paper allows for variation in the falls risk assessment and falls prevention program utilized in the ALC based on the resident population living in the ALC. It clearly outlines a vision for falls prevention (Kotter’s third step) within an ALC. The flowchart provides a structure of the falls prevention process that is appropriate for multiple populations residing in ALCs and identifies the components and inter-relationships within the components of this process.

This structured falls prevention process starts with an assessment of a resident’s falls risk at admission. The risk assessment should follow the current AGS/BGS recommendations (Kenny et al., 2011) and ensure that all older individuals be asked about their falls history or difficulty with gait or balance. If the individual responds positively to either question, then a multifactorial falls risk assessment comprised of components outlined by the AGS/BGS should be conducted as indicated (Kenny et al., 2011). Across our small sample, we found inconsistency in the falls risk assessment components. The variation in falls risk assessments indicates that further research is needed to identify what components are included by ALCs when conducting a falls risk assessment and how they align with AGS/BGS recommendations for assessing falls risk.

Prior studies also identified the importance of tailoring a falls risk assessment for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Anstey, Von Sanden, & Luszcz, 2006; Brady & Lamb, 2008; Hsieh, Rimmer, & Heller, 2012). In Wisconsin, 97% of licensed Adult Family Homes and 49% of Community Based Rehabilitation Facilities provide services to residents with cognitive impairments and behavioral issues (WIBAL, 2015). Within these populations, resident balance and gait, impulsivity, and cognition may be related to an increased falls risk (Enkelaar, Smulders, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, Geurts, & Weerdesteyn, 2012; Ferrari, Harrison, & Lewis, 2012; Whitney, Close, Jackson, & Lord, 2012). In our sample, the assessment process used by two ALCs (15%) included questions related to impulsivity, and one ALC raised the issue of impulsivity and its relationship to falls. While the Tinetti and Berg falls risk assessment tools may predict falls risk for individuals with intellectual and development disabilities, these instruments do not address impulsivity (Chiba et al., 2009; Oppewal, Hilgenkamp, van Wijck, & Evenhuis, 2013). Since a significant proportion of Wisconsin ALCs provide care for these individuals, further research is recommended to study whether additional questions related to impulsivity and fall risk would be relevant within cognitive assessment tools used in these ALCs.

The study showed a lack of consistent use of falls prevention programs in the ALCs interviewed as well as in Coalition ALCs. ALCs participating in the Coalition likely represent communities making a greater than the average effort to improve quality in their organizations. As such, the actual number of Wisconsin ALCs without a falls prevention program may likely be higher. Barriers to implementing a falls prevention program identified included a lack of a perception of need for such a program, no corporate-wide strategy related to falls prevention, and difficulty choosing a program given the overwhelming amount of information available related to falls prevention. The absence of staff, staff time and characteristics unique to rural and urban settings have also been identified as barriers to implementing falls prevention education (Zachary, Casteel, Nocera, & Runyan, 2012). Further research is needed to determine if these barriers to implementing falls prevention programs are present in ALCs.

The interviewees verified that ALC staff would like further education about the importance of falls prevention in ALCs, guidelines on how to choose and implement a falls prevention program, and suggestions on how to improve resident motivation for participation in falls prevention programs. Resident motivation to participate in a falls prevention program was identified as a barrier. For example, RCAC’s are an independent living setting, and it may be more difficult for ALC staff to promote participation in a falls prevention process for residents living in RCAC’s. A systematic review examined older people’s perceptions of participation in falls prevention programs (Bunn, Dickinson, Barnett-Page, Mcinnes, & Horton, 2008). Facilitators included social support, low-intensity exercise, greater education, involvement in decision-making, and a perception of the programs as relevant and life-enhancing. Barriers included fatalism, denial, and under-estimation of the risk of falling, poor self-efficacy, no previous history of exercise, fear of falling, poor health and functional ability, low health expectations and the stigma associated with programs targeted to an older population. Further research about ALC resident motivation to participate in a falls prevention program is needed.

The proposed falls prevention process for ALCs delineated in the flowchart (Figure 2) also highlights the importance of the communication processes including documentation and tracking of falls, as well as resident and ALC specific feedback (Kotter Step 4). It would be expected that a given ALC would have a process for sharing and communicating information about their specific falls prevention program. In our sample, this communication process appear to exist for 66% of the respondents; however, the results also indicate opportunities for improvement. For example, 57% of the falls prevention questionnaire respondents did not specifically indicate how often (e.g., monthly) information about the falls prevention program is shared across the ALC. In addition, a falls communication process should establish a consistent internal process for notifying family and a resident’s primary care physician about their falls risk or a specific falls incident. A robust communication process would serve to identify short-term wins by reducing falls (Kotter Step 6) and encourage continued action of either the current falls prevention plan or a modification of the current plan to address resident falls risks (Kotter Step 5).

When a fall occurs within an ALC, we would expect a 1:1 match between a resident specific reporting event and the development and introduction of a resident specific follow-up intervention to prevent future falls. However, the questionnaire indicates that 62% of the ALCs responding have a resident specific reporting process and only 52% reported having some type of follow-up intervention. Within the proposed falls prevention process for ALCs, a fall should trigger a post falls assessment (following AGS/BGS guidelines) and include an in-depth root cause analysis into the resident’s fall. Once completed, ALC staff should implement a series of actions to prevent future falls. These efforts should focus on the implementation of AGS/BGS recommendations (Kenny et al., 2011). Although process implementation may require additional staff time, respondent feedback did not identify staff burden as a potential implementation barrier. Further staff education is needed to facilitate the implementation of these actions and research required to understand the potential impact on ALC staffing.

Not all aspects of Kotter’s change model are addressed by the falls prevention process flowcharts. (Kotter, 1995) The second step, building a guiding team, is not identified in the falls prevention model as developed. Identifying a falls prevention champion within an ALC may increase the likelihood of adoption and implementation of a falls prevention process, but further study is needed to identify the characteristics of this role. Kotter’s final two steps, which identify methods for sustaining change, were not specifically addressed within the falls prevention process highlighted in this paper. Further study is warranted to identify successful strategies for maintaining falls prevention strategies in ALCs.

LIMITATIONS

The Coalition members requested ALC anonymity on the questionnaire. However, the ALCs interviewed were recommended by the Coalition members. As such, there was no identifiable linkage between the questionnaire and interview responses. The ALCs responding to the falls prevention questionnaire or those who were interviewed represented a small sample of ALCs in Wisconsin and was also limited only to Coalition members. The approach to falls preventions utilized in these communities may not be completely representative of all Wisconsin ALCs or ALCs in general, limiting the generalizability of the results. Study participation was voluntary. As such, the sample of respondents to both the voluntary questionnaire and interview samples may not be representative of all Coalition members. The data about falls prevention programs is self-reported, and it is possible that a community may have a falls prevention program but did not accurately report its use. Data collected was also limited to the scope of questions asked on the falls prevention questionnaire and interviews. The limited amount of previous research on falls prevention in assisted living makes it difficult to verify these findings.

CONCLUSION

The falls prevention process flow charts incorporate existing components of falls prevention processes currently used in Wisconsin ALCs. In turn, the flowcharts provides a compressive, standardized, proactive approach to addressing the falls prevention process in these communities and a baseline for further assisted living specific falls prevention research. Research funded by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) identified similar processes for hospital-related falls prevention that focused on a universal falls precaution protocol (AHRQ, 2013). A similar falls process flow chart was developed for skilled nursing facilities, but the flow chart process highlights a post fall response in nursing homes, not a prevention model (AHRQ, 2014). Research on falls prevention and the falls prevention process in ALCs is limited. Further research is needed to determine if the process delineated in this study can assist ALCs in organizing and implementing a comprehensive falls prevention process to aid in falls reduction for all their residents.

Acknowledgments:

J Ford and S.Nordman-Oliveira planned the study and obtained funding, supervised the data analysis, conducted the interviews, participated in the data analysis and contributed to the development and revision of the paper. D. Coughlin conducted the interviews, participated in the data analysis, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and assisted in revising the paper. M. Schlaak transcribed the interviews, participated in the data analysis and contributed to revisions of the paper. We express appreciation to Dr. David Zimmerman, Kevin Coughlin, Heather Bruemmer and staff from the four Wisconsin Assisted Living Associations: LeadingAge Wisconsin; Wisconsin Assisted Living Association (WALA); Wisconsin Center for Assisted Living (WiCAL) and Residential Services Association of Wisconsin (RSA WI) for their review of the manuscript. We would also like to thank the four Assisted Living Associations for their support of the project and express our gratitude to the ALC staff who participated in the interviews and responded to the questionnaire.

Funding

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Project team members have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

DaRae Coughlin, Center for Health Systems Research and Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Susan Nordman-Oliveira, Center for Health Systems Research and Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Mary Schlaak, Center for Health Systems Research and Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

James H. Ford, II, Center for Health Systems Research and Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- AGS B (2011). Guidelines for the prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 49, 664–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. (2013). Tool 3A: Master Clinical Pathway for Inpatient Falls. Content last reviewed January 2013. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/fallpxtoolkit/fallpxtk-tool3a.html

- AHRQ. (2014). Chapter 2. Fall Response. Content last reviewed October 2014. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/long-term-care/resources/injuries/fallspx/fallspxman2.html [Google Scholar]

- Alamgir H, Muazzam S, & Nasrullah M (2012). Unintentional falls mortality among elderly in the United States: time for action. Injury, 43(12), 2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, & Hausdorff JM (2013). Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas, 75(1), 51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey KJ, Von Sanden C, & Luszcz MA (2006). An 8-Year Prospective Study of the Relationship Between Cognitive Performance and Falling in Very Old Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(8), 1169–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady R, & Lamb V (2008). Assessment, intervention, and prevention of falls in elders with developmental disabilities. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 24(1), 54–63. doi: 10.1097/01.TGR.0000311406.01555.e0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E, Mcinnes E, & Horton K (2008). A systematic review of older people’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls-prevention interventions. Ageing and Society, 28(04), 449–472. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X07006861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2017). Center for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Retrieved from URL: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. 2017-Nov-07 [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Shimada A, Yoshida F, Keino H, Hasegawa M, Ikari H, … Hosokawa M (2009). Risk of fall for individuals with intellectual disability. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 114(4), 225–236. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-114.4:225-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, & Ortman JM (2015). Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. US Census Bureau, Ed, 25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, & Sharit J (2009). The aging of the population: opportunities and challenges for human factors engineering. Bridge: Linking Eng Soc, 39, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Egan-Robertson D (2013). Wisconsin’s Future Population: Projections for the State, Its Counties and Municipalities, 2010–2040.

- Enkelaar L, Smulders E, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H., Geurts AC, & Weerdesteyn V (2012). A review of balance and gait capacities in relation to falls in persons with intellectual disability. Research in developmental disabilities, 33(1), 291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Harrison B, & Lewis D (2012). The Risk Factors for Impulsivity-Related Falls Among Hospitalized Older Adults. Rehabilitation Nursing, 37(3), 145–150. doi: 10.1002/RNJ.00046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieson C, Foote D, Frith K, & Wagner III J (2012). Utilizing Change Theory to Implement a Quality Improvement, Evidence-based Fall Prevention Model in Long-term Care. J Gerontol Geriat Res S, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Florence C, Baldwin G, Stevens J, & McClure R (2016). The CDC Injury Center’s response to the growing public health problem of falls among older adults. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 10(1), 74–77. doi: 10.1177/1559827615600137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K, Rimmer J, & Heller T (2012). Prevalence of falls and risk factors in adults with intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil, 117(6), 442–454. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.6.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A (2016). Bureau of Assisted Living: State of Assisted Living Annual Report 2015. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/regulations/assisted-living/bal-state-assisted-living-2015.pdf

- Kenny R, Rubenstein LZ, Tinetti ME, Brewer K, Cameron KA, Capezuti L, … Rockey PH (2011). Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(1), 148–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter JP (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail.

- Mather M, Jacobsen L, & Pollard K (2015). Aging in the United States. Popultion Bulletin, 70 (2). [Google Scholar]

- McGough EL, Logsdon RG, Kelly VE, & Teri L (2013). Functional mobility limitations and falls in assisted living residents with dementia: physical performance assessment and quantitative gait analysis. Journal of geriatric physical therapy, 36(2), 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppewal A, Hilgenkamp TI, van Wijck R, & Evenhuis HM (2013). Feasibility and outcomes of the Berg Balance Scale in older adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities, 34(9), 2743–2752. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, & Hogan H (2014). An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JJ, & Heuvel LNV (2004). Root cause analysis for beginners. Quality Progress, 37(7), 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stock KJ, Amuah JE, Lapane KL, Hogan DB, & Maxwell CJ (2017). Prevalence of, and Resident and Facility Characteristics Associated With Antipsychotic Use in Assisted Living vs. Long-Term Care Facilities: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Alberta, Canada. Drugs & Aging, 34(1), 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TJC. (2016a). National Patient Safety Goals: Home Care Accreditation Program. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2016_NPSG_OME.pdf

- TJC. (2016b). National Patient Safety Goals: Long Term Care Accreditation Program Medicare/Medicaid Certification-based Option. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2016_NPSG_LT2.pdf

- Whitney J, Close JC, Jackson SH, & Lord SR (2012). Understanding risk of falls in people with cognitive impairment living in residential care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(6), 535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIBAL. (2015). Falls in Assisted Living Facilities. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p00994.pdf

- WIDHS. Wisconsin State Legislature: Subchapter VI - Resident Rights and Protections (DHS93.32(2)n. Retrieved from http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/dhs/030/83/VI/32/3/n

- WIDHS. (12 August 2016). Wisconsin Department of Health Services Consumer Guide to Health Care - Finding and Choosing an Assisted Living Facility. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/guide/assisted-living.htm

- WIDHS. (21 July 2016). Wisconsin Interactive Statistics on Health (WISH): Injury-Related Hospitalization Module. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/wish/injury-hosp/index.htm

- Zachary C, Casteel C, Nocera M, & Runyan CW (2012). Barriers to senior centre implementation of falls prevention programmes. Injury prevention, 18(4), 272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]