Abstract

Methylmercury (CH3Hg+), a common environmental toxicant, has serious detrimental effects in numerous organ systems. We hypothesize that a significant physiological change, like pregnancy, can alter the disposition and accumulation of mercury. To test this hypothesis, pregnant and non-pregnant female Wistar rats were exposed orally to CH3Hg+. The amount of mercury in blood and total renal mass was significantly lower in pregnant rats than in non-pregnant rats. This finding may be due to expansion of plasma volume in pregnant rats and dilution of mercury, leading to lower levels of mercury in maternal blood and kidneys.

Introduction

Mercury is a unique, toxic metal found ubiquitously in the environment. Most humans are exposed to mercury through ingestion of contaminated fish. Atmospheric mercury settles into bodies of water and is biotransformed to CH3Hg+, which then bioaccumulates in many species of freshwater and saltwater fish. Humans who eat large quantities of contaminated fish are exposed to potentially toxic levels of mercury that may accumulate in the kidneys, brain, and blood. Fecal and urinary excretion is minimal without chelation therapy. Despite warnings from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), many women of childbearing age continue to ingest more than the recommended amount of fish [1]. Indeed, detectable levels of mercury have been found in blood of women across the USA [2, 3]. Interestingly, a study in Long Island, NY, found that even when fish consumption was at or below the current recommended amounts, mercury levels in blood were greater than those considered safe by the EPA [4]. Exposure to mercuric compounds continues to be a significant problem around the world. Therefore, it is important to understand how mercury is handled under different physiologic circumstances.

Pregnancy leads to numerous physiological changes in mothers and, as noted above, women continue to be exposed to mercury. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to determine if pregnancy alters the disposition of CH3Hg+ in maternal organs. In pregnant women, plasma volume increases by approximately ~40% [5]. This volume expansion may alter hemodynamics and handling of toxicants such as mercury [6]. Following exposure, a large fraction of CH3Hg+ is present in blood [7] and may be delivered readily to the placenta and fetus [8–11]. Therefore, we hypothesized that pregnancy may lessen the accumulation of CH3Hg+ in select maternal organs/tissues.

Materials and Methods

Adult Wistar rats were obtained from Mercer University School of Medicine vivarium. Rats were mated for 36 h and vaginal swabs were performed to confirm pregnancy. Throughout the experiment, rats were provided a standard laboratory diet (Tekland 6% rat diet, Envigo Laboratories) and water ad libitum. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under the guidelines of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted by the National Institutes of Health.

Radioactive mercury ([203Hg]) was made at the Missouri University Research Reactor as described previously [12, 13]. Subsequently, radioactive methylmercury (CH3[203Hg]) was generated following a previously published protocol [8] as adapted from Rouleau and Block [14].

Pregnant and non-pregnant female Wistar rats were exposed to three non-toxic doses of radioactive CH3Hg+ (2 mg/kg in 5 mL saline containing 1 μCi of CH3[203Hg] per rat) by oral gavage on gestational days (GD) 10, 15, and 19. Non-pregnant rats were gavaged according to the same time frame. On GD 20, rats were anesthetized with an intra-peritoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (70/30 mg kg−1). In each animal, the kidneys and blood were collected for determination of CH3[203Hg] content [15]. Samples were counted in a Wallac Wizard 3 automatic gamma counter (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA). All data were analyzed with a Student’s t test using a p value of < 0.05. Each group of animals contained six rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SE.

Results and Discussion

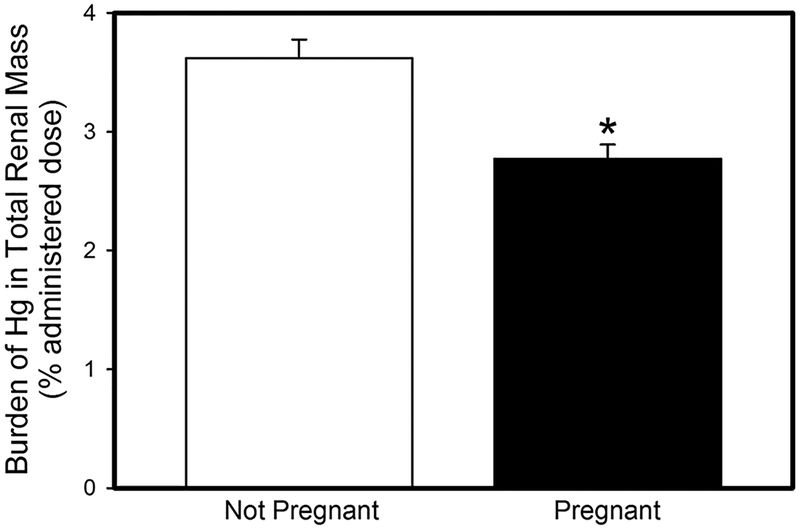

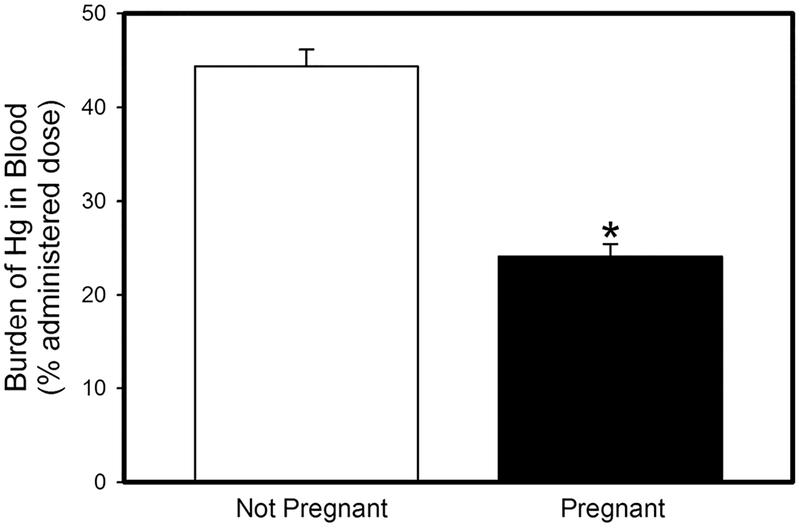

Women of childbearing age continue to be exposed to mercury via seafood consumption despite EPA guidelines. Handling of mercury by pregnant women is of particular concern because of the risk of fetal exposure. Pregnancy leads to an increase in plasma volume in order to adequately supply nutrients to the placenta and fetus. We hypothesize that changes, such as an increase in blood volume, lead to significant differences in the maternal handling of mercury. Indeed, when pregnant and non-pregnant female rats were exposed orally to CH3Hg+, the renal burden of CH3Hg+ in pregnant rats was significantly lower than that in corresponding non-pregnant rats (Fig. 1). This difference could not be accounted for by urinary excretion of CH3Hg+, which was less than 1% of the administered dose in both, pregnant and non-pregnant rats. The amount of mercury in blood was also lower in pregnant females than in non-pregnant females (Fig. 2). We suggest that as blood volume increases, the concentration of CH3Hg+ in blood is decreased. Additionally, a fraction of the dose of CH3Hg+ is delivered to and accumulates in the placenta (2.5 ± 0.9% administered dose) and fetal tissues (9.2 ± 1.7% administered dose). Although renal plasma flow and GFR are increased in pregnant women, the amount of CH3Hg+ delivered to maternal organs via blood appears to be reduced. This reduction is likely a consequence of placental circulation and delivery of CH3Hg+ and nutrients to the placenta and fetuses.

Fig.1.

Amount of mercury (% administered dose) in total renal mass of pregnant and non-pregnant rats after being exposed orally to three doses of 2.5 mg kg−1 CH3Hg+, containing 1 μCi CH3[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of six rats. *Significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean for the non-pregnant group of rats

Fig. 2.

Amount of mercury (% administered dose) in blood of pregnant and non-pregnant rats after being exposed orally to three doses of 2.5 mg kg−1 CH3Hg+, containing 1 μCi CH3[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of six rats. *Significantly different (p <0.05) from the mean for the non-pregnant group of rats

While pregnancy may seem to reduce the risk of mercury accumulation in maternal organs and may be considered to be protective, pregnant women must first consider the risk of CH3Hg+ exposure on the developing fetus. Ingestion of large quantities of fish during pregnancy may not lead to signs and symptoms of mercury intoxication in the mother, partly because of hematologic dilution of the dose of mercury. Interestingly, the concentration of mercury in cord blood has been shown to be greater than that in maternal blood [16–18] suggesting that the fetus may be exposed to greater concentrations of mercury than the mother. The possibility of mercury-induced fetal injury emphasizes the importance of studying and understanding the way mercury is handled in pregnant women. In summary, the current data indicate that the disposition of mercury differs in pregnant and non-pregnant females. These differences suggest that significant physiological or pathological changes may lead to alterations in the handling of mercuric ions within the body.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (ES019991) and Navicent Health Foundation awarded to Dr. Bridges.

References

- 1.Monastero R, Karimi R, Silbernagel S, Meliker J (2016) Demographic profiles, mercury, selenium, and omega-3 fatty acids in avid seafood consumers on Long Island, NY. J Com Health 41:165–173. 10.1007/s10900-015-0082-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cusack LK, Smit E, Kile ML, Harding AK (2017) Regional and temporal trends in blood mercury concentrations and fish consumption in women of child bearing Age in the united states using NHANES data from 1999–2010. Environ Health: A global Access Sci Source 16:10 10.1186/s12940-017-0218-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karouna-Renier NK, Ranga Rao K, Lanza JJ, Rivers SD, Wilson PA, Hodges DK, Levine KE, Ross GT (2008) Mercury levels and fish consumption practices in women of child-bearing age in the Florida Panhandle. Environ Res 108:320–326. 10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karimi R, Silbernagel S, Fisher NS, Meliker JR (2014) Elevated blood Hg at recommended seafood consumption rates in adult seafood consumers. Int J Hyg Environ Health 217:758–764. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hytten F (1985) Blood volume changes in normal pregnancy. Clinics in Haematology 14:601–612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West CA, Sasser JM, Baylis C (2016) The enigma of continual plasma volume expansion in pregnancy: critical role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311:F1125–F1134. 10.1152/ajprenal.00129.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zalups RK, Bridges CC (2009) MRP2 involvement in renal proximal tubular elimination of methylmercury mediated by DMPS or DMSA. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 235:10–17. 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK (2009) Effect of DMPS and DMSA on the placental and fetal disposition of methylmercury. Placenta 30:800–805. 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK (2012) Placental and fetal disposition of mercuric ions in rats exposed to methylmercury: role of Mrp2. Reprod Toxicol 34:628–634. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto M, Yasutake A, Domingo JL, Chan HM, Kubota M, Murata K (2013) Relationships between trace element concentrations in chorionic tissue of placenta and umbilical cord tissue: potential use as indicators for prenatal exposure. Env Int 60:106–111. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yorifuji T, Tsuda T, Takao S, Suzuki E, Harada M (2009) Total mercury content in hair and neurologic signs: historic data from Minamata. Epidemiology 20:188–193. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190e73f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanger M, Westin A, Barfuss DW (2001) Some health physics aspects of working with 203Hg in university research. Health Phys 80(2 Suppl):S28–S30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridges CC, Bauch C, Verrey F, Zalups RK (2004) Mercuric conjugates of cysteine are transported by the amino acid transporter system b(0,+): implications of molecular mimicry. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:663–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouleau C, Block M (1997) Fast and high yield synthesis of radioactive CH3203Hg(II). Appl Organomet Chem 11:751–753 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK (2008) Multidrug resistance proteins and the renal elimination of inorganic mercury mediated by 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonic acid and meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324:383–390. 10.1124/jpet.107.130708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong CN, Chia SE, Foo SC, Ong HY, Tsakok M, Liouw P (1993) Concentrations of heavy metals in maternal and umbilical cord blood. Biometals 6:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y, Lee CK, Kim KH, Lee JT, Suh C, Kim SY, Kim JH, Son BC, Kim DH, Lee S (2016) Factors associated with total mercury concentrations in maternal blood, cord blood, and breast milk among pregnant women in Busan, Korea. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr 25:340–349. 10.6133/apjcn.2016.25.2.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soon R, Dye TD, Ralston NV, Berry MJ, Sauvage LM (2014) Seafood consumption and umbilical cord blood mercury concentrations in a multiethnic maternal and child health cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 14:209 10.1186/1471-2393-14-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]