Abstract

Background

Objective and longitudinal measurements of disability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are desired in order to monitor disease status and response to disease-modifying and symptomatic therapies. Technology-enabled comprehensive assessment of MS patients, including neuroperformance tests (NPTs), patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and MRI, is incorporated into clinical care at our center. The relationships of each NPT with PROMs and MRI measures in a real-world setting are incompletely studied, particularly in larger datasets.

Objectives

To demonstrate the utility of comprehensive neurological assessment and determine the association between NPTs, PROMs, and quantitative MRI measures in a large MS clinical cohort.

Methods

NPTs (processing speed [PST], contrast sensitivity [CST], manual dexterity [MDT], and walking speed [WST]) and physical disability-related PROMs (Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders [Neuro-QoL], Patient Determined Disease Steps [PDDS], and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global-10 [PROMIS-10] physical) were collected as part of routine clinical care. Fully-automated MRI analysis calculated T2-lesion volume (T2LV), whole brain fraction (WBF), thalamic volume (TV), and cervical spinal cord cross-sectional area (CA) for brain MRIs completed within 3 months of a clinic visit during which NPTs and PROMs were assessed. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients evaluated the cross-sectional associations of NPTs with PROMs and MRI measures. Linear regression was utilized to determine which combination of clinical characteristics, patient demographics, MRI measures, and PROMs best cross-sectionally explained each NPT result.

Results

997 unique patients (age 47.7±11.4 years, 71.8% female) who underwent assessments over a 2-year period were included. Correlations among NPTs and PROMs were moderate. PST correlations were strongest for Neuro-QoL upper extremity (NQ-UE) (Spearman’s rho = 0.43) and lower extremity (NQ-LE) (0.47). CST correlations were strongest for NQ-UE (0.33), NQ-LE (0.36), and PDDS (−0.31). MDT correlations were strongest for NQ-UE (−0.53), NQ-LE (−0.54), and PDDS (0.53). WST correlations were strongest for PDDS (0.64) and NQ-LE (−0.65). NPTs also had moderate correlations with MRI metrics, the strongest of which were observed with PST (with T2LV (−0.44) and WBF (0.49)). Spearman’s rho for other NPT-MRI correlations ranged from 0.23 to 0.36. Linear regression identified age, disease duration, PROMIS-10 physical, NQ-UE, NQ-LE, T2LV and WBF as significant cross-sectional explanatory variables for PST (adjusted R2=0.46). For CST, significant variables included age and NQ-LE (adjusted R2 = 0.30). For MDT, significant variables included PDDS, PROMIS-10 physical, NQ-UE, NQ-LE, T2LV, and WBF (adjusted R2=0.37). For WST, significant variables included sex, PDDS, NQ-LE, T2LV, and CA (adjusted R2=0.39).

Conclusions

Impaired performance on NPTs correlated with worse physical disability-related PROMs and MRI disease severity, but the strongest cross-sectional explanatory variables for each NPT component varied. This study supports the use of comprehensive, objective quantification of MS status in clinical and research settings. Future longitudinal analyses can determine predictors of treatment response and disability worsening.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Outcome measurement, Quality of life, Quantitative MRI, Patient-reported outcome measures

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated disease resulting in accumulation of neurological disability. American and European Academy of Neurology guidelines recommend longitudinal objective measures of disability in MS clinical care (Montalban et al., 2018; Rae-Grant et al., 2015). Such assessment of MS in clinical practice should involve assessments of multidomain disability, quality of life, and disease activity to identify disease worsening and determine treatment response.

Comprehensive quantitative MS assessment, including technology-enabled neuroperformance tests (NPTs), patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and quantitative MRI analysis, has been developed and incorporated into clinical practice at our center for this purpose (Rhodes et al., 2019). Assessments are self-administered and can be performed in the office by the patient with minimal to no assistance or supervision. NPTs in this assessment are modeled after the components of the MS Functional Composite (MSFC), a multidimensional measure of MS-related disability widely used in both clinical and research settings (Fischer et al., 1999). NPTs are intended to objectively capture disability related to cognition, visual function, dexterity, and ambulation (Balcer et al., 2003; Fischer et al., 1999; Ontaneda et al., 2012).

Patient-reported quality of life measures also provide crucial information regarding disease status, given the varied clinical manifestations of MS. Though rarely performed in practice, PROMs can complement the information provided by NPTs and quantitative MRI, providing improved focus in symptomatic management during a clinical encounter. In order to evaluate the relative contributions of PROMs and quantitative MRI metrics to physical disability for purposes of informing future longitudinal analyses, the major objective of this study was to determine the associations between NPTs, physical disability-related PROMs, and quantitative MRI measures implemented in large clinical cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

All patients with MS at the Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) undergo technology-enabled NPT and PROM assessment via iPad® as part of standard clinic visits. Patients seen between December 2015 and December 2017 with a brain MRI available within 3 months of a clinic visit in which at least one NPT and one PROM were assessed were included in these analyses. We performed a cross-sectional analysis with the first chronologically available visit from each patient. Approval from an ethical standards committee (Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board) to conduct this study was received (#18–313). Data were collected as part of routine clinical care, therefore informed consent was not required.

2.2. Neuroperformance Measures

Technology-enabled NPTs performed via iPad® were developed, validated, and implemented at our institution as part of clinical care (Rao et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2019; Rudick et al., 2014). Details regarding NPT acquisition are reported in the Supplemental Appendix, and have also been previously described (Rhodes et al., 2019). The Processing Speed Test (PST) is an adaptation of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), the Contrast Sensitivity Test (CST) for Sloan Low Contrast Letter Acuity (LCLA), the Manual Dexterity Test (MDT) for 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT), and Walking Speed Test (WST) for Timed 25-foot Walk (T25FW). The Multiple Sclerosis Performance Tests (MSPT), which encompasses these NPTs, PROMs, and quantitative MRI, was developed at the Cleveland Clinic.

2.3. Patient Reported Outcome Measures

PROMs administered via iPad® include: 1) the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) (Kroenke et al., 2001), 2) Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL) (Gershon et al., 2012), a series of health-related questions that capture aspects of physical, mental, and social health specific to neurological diseases, 3) Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) (Learmonth et al., 2013), a patient-reported version of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), a common measure of disability utilized in MS that is primarily focused on ambulation, and 4) the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global-10 (PROMIS-10) physical and mental health domain t-scores (HealthMeasures, 2018).

PDDS, PROMIS-10 physical health, and both upper (UE) and lower extremity (LE) Neuro-QoL domains were utilized as PROMs for this study, as it was intended to focus on physical disability.

2.4. Quantitative MRI Measures

MRIs were acquired within 3 months of a clinical encounter at which NPTs and PROMs were analyzed. Detailed MRI methods are presented in the Supplementary Appendix.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Cross-sectional associations between NPTs, PROMs, and MRI measures were evaluated via Spearman correlation coefficients. The statistical significance threshold for these correlations was set at p<0.001 to account for multiple comparisons; a Bonferroni method for p-value adjustment was utilized to maintain overall alpha = 0.05. Single imputation was performed for missing PROM and MRI data using predictive mean matching and robust linear modeling hot-deck imputation methods, as there was less than approximately 20% of data missing for any PROM or MRI metric. Missing data in NPTs were not imputed. Results using imputed and complete case data were compared qualitatively for any substantial differences. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to compare patients with and without missing data via unpaired t-tests. Patients with Clinically or Radiologically Isolated Syndromes (CIS/RIS) were excluded for a sensitivity analysis as well. Guidance for MSPT component and correlation coefficient interpretations is presented in Table 1.

Table 1–

MSPT Component Interpretation

| Test Name | Scoring Element | Scoring Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroperformance Tests | Processing Speed Test (PST) | Number of correct responses | Higher score → better performance |

| Contrast Sensitivity Test (CST) | Number of letters correctly named at 2.5% contrast | Higher score → better performance | |

| Manual Dexterity Test (MDT) | Time to complete task (in seconds) | Higher score → worse performance | |

| Walking Speed Test (WST) | Time to walk 25 feet (in seconds) | Higher score → worse performance | |

| Patient Reported Outcomes | Patient Determined Disease Steps | Reported score (010) | Higher score → worse disability |

| PROMIS-10 physical health t-score | Calculated t-score (20–80) | Higher score → better function | |

| Neuro-QoL upper extremity function | Calculated t-score (20–80) | Higher score → better function | |

| Neuro-QoL lower extremity function | Calculated t-score (20–80) | Higher score → better function | |

| Quantitative MRI | T2 lesion volume | Volume in mL | Higher volume → worse disease |

| Whole brain fraction | Fraction (0–1) | Higher fraction → less severe disease | |

| Thalamic volume | Volume in mL | Higher volume → less severe disease | |

| Cervical spinal cord area | Area in mm2 | Higher area → less severe disease |

Linear regression models for each NPT were selected via automated backwards stepwise regression utilizing Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) to determine which combination of measures (either PROMs or MRI) best cross-sectionally explained the respective NPT result. Regression model terms were considered significant if p < 0.05. The model generated for each NPT was then compared to a model that included all independent variables of interest via adjusted R-squared, overall model F-test p-value, Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), and ANOVA testing for nested models. For linear regression modeling, transformations were guided via Box-Cox methods: CST was squared, MDT was inversely transformed, and the square root of WST was used for due to non-normality. The normality of transformed variables was assessed via visual inspection of histograms. Potential confounders were investigated, including age, sex, and disease duration (years). Collinearity was assessed via variance inflation factors (VIF), with final models required to have VIF<5. All regression coefficients were fully standardized. A final model was described for each NPT.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R Statistical Software (version 3.4.4) simputation (version 0.2.2), tidyverse (version 1.2.1), stats (version 3.4.4), car (version 3.0–2) and ggplot2 (version 3.0.0) packages. Confidence intervals for Spearman’s rho were calculated using the package spearmanCI (version 1.0), using a jackknife Euclidean likelihood-based method (de Carvalho and Marques, 2012).

2.6. Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared with qualified investigators by request from the corresponding author for purposes of replicating procedures and results.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

Between December 2015 and December 2017, 997 patients underwent NPT and PROM assessment as part of clinical care, with an appropriately timed brain MRI available. Following single imputation of PROM and MRI data, variable missingness in outcomes necessitated utilization of separate datasets for each NPT, yielding 840 patients for PST, 476 for CST, 880 for MDT, and 840 for WST. There were 976 patients overall included in the final analysis, as 21 patients had missing data in characteristics used for imputation. Patient characteristics, NPT, PROM, and MRI data for the original (n = 997) and final imputed samples (n = 976) are summarized in Table 2, and the populations were overall similar. Patients in the original population were predominantly female (71.9%), Caucasian (82.9%), and had relapsing-remitting MS (76.9%). All subsequent results presented are derived from the final imputed sample (n = 976).

Table 2–

Patient characteristics

| Non-imputed (n = 997)a | Final Imputed (n = 976)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age (mean (SD)) | 47.7 (11.4) | 47.7 (11.4) |

| Sex (% (n) female) | 71.9 (717) | 71.8 (701) | |

| Race (% (n)) | |||

| Caucasian | 82.9 (827) | 83.6 (816) | |

| African-American | 12.8 (128) | 12.3 (120) | |

| Other | 3.1 (31) | 3.0 (29) | |

| Unknown | 1.1 (11) | 1.1 (11) | |

| Clinical characteristics | MS phenotype (% (n)) | ||

| Relapsing-remitting | 76.9 (76 ) | 77.8 (759) | |

| Secondary progressive | 12.7 12 ) | 11.8 (115) | |

| Primary progressive | 4.5 (45) | 4.5 (44) | |

| CIS/RIS | 5.8 (58) | 5.9 (58) | |

| MS disease duration (years, mean (SD)) | 12.4 9.6) | 12.3 (9.4) | |

| Neuroperformance metrics | Walking speed test (seconds, median PQR]) | 6.56 [5.4, 8.9] | 6.56 [5.4, 8.9] |

| Manual dexterity test, dominant hand (seconds, median [IQR]) | 26.68 [22.9, 32.3] | 26.59 [22.8, 32.0] | |

| Manual dexterity test, non-dominant hand (seconds, median [IQR]) | 27.79 [24.0, 33.8] | 27.69 [24.0, 33.4] | |

| Processing speed test (# correct, median [IQR]) | 48.00 [39.0, 57.0] | 48.00 [39.0, 57.0] | |

| Contrast sensitivity test (# correct, median [IQR]) | 34.00 [25.0, 41.0] | 34.00 [24.75, 41.0] | |

| Patient reported outcome measurer | Patient Determined Disease Steps (median [IQR]) | 1.0 [0, 3.0] | 1.0 [0, 3.0] |

| PROMIS-10 physical health t-score (median [IQR]) | 39.80 [37.4, 44.9] | 39.80 [37.4, 44.9] | |

| Neuro-QoL upper extremity function (median [IQR]) | 42.27 [37.5, 56.8] | 42.77 [37.8, 49.8] | |

| Neuro-QoL lower extremity function (median [IQR]) | 44.40 [36.9, 53.3] | 44.40 [37.3, 53.5] | |

| MRI metrics | T2 lesion volume (mL, median [IQR]) | 9.33 [4.0, 20.6] | 9.22 [4.0, 20.0] |

| Whole brain fraction (median [IQR]) | 0.83 [0.80, 0.84] | 0.83 [0.80, 0.84] | |

| Cervical spinal cord area (mm2, median [IQR]) | 76.42 [70.3, 81.9] | 76.60 [70.9, 81.5] | |

| Thalamic Volume (mL, median [IQR]) | 15.94 [14.5, 17.1] | 15.95 [14.6, 17.0] |

Overall n = 997 prior to imputation; missingness in individual variables is indicated as follows: disease duration (n = 16), Walking speed test (WST, 154), Manual dexterity test dominant and non-dominant hands (MDT, 101), Processing speed test (PST, 147), Contrast sensitivity test (CST, 520), Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS, 53), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-10 (PROMIS-10, 70), Neuro-QoL upper extremity (223), Neuro-QoL lower extremity (216), T2 lesion volume (22), Whole brain fraction (11), Cervical spinal cord area (56), and Thalamic volume (85).

Following imputation, n = 976 due to missingness of all PROMs (PDDS, Neuro-QoL upper/lower extremity, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, PROMIS-10) in 21 patients from the original dataset that were not imputed. Missingness in individual variables in the final imputed dataset is indicated as follows: WST (n = 136), MDT dominant and non-dominant hands (96), PST (136), CST (500).

Neuroperformance Test Correlations

All correlation coefficients indicated that worse performance on each NPT correlated with worse performance on other NPTs, worse self-reported function, or increased disease severity on quantitative MRI measures. All reported correlations were significant (p<0.001).

3.1.1. Associations Among Neuroperformance Tests

PST correlated with CST (Spearman’s rho = 0.55, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.62), dominant hand MDT (rho = −0.63, 95% CI −0.67 to −0.57), and WST (rho = −0.50, 95% CI −0.55 to −0.44). CST correlated with dominant hand MDT (rho = −0.41, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.33), and WST (rho = −0.33, 95% CI −0.41 to −0.24). Dominant hand MDT correlated with WST (rho = 0.58, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.63). Dominant and non-dominant hand MDT were strongly correlated (rho = 0.78, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.81). Correlations between non-dominant hand MDT and other NPTs were similar to that of dominant hand MDT.

3.1.2. Association of Neuroperformance Tests with PROMs

Each NPT was investigated for correlation with PROMs reflecting physical disability (Figures 1 and 2). PST was significantly correlated with all PROMs (p<0.001); there was a moderate correlation with PDDS (Spearman’s rho = −0.44, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.38), Neuro-QoL UE (rho = 0.43, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.49), and Neuro-QoL LE (rho = 0.47, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.52).

Figure 1 – Scatterplot Matrix of PROMs and Neuroperformance Tests.

Scatterplots for each patient reported outcome measure (PROM) and Neuroperformance Test relationship are presented in the imputed sample (n = 976). The line represents a linear regression line for each relationship. PST: Processing speed test (n = 840); CST: Contrast sensitivity test (n = 476); MDT: Manual dexterity test (dominant hand) (n = 880); WST: Walking speed test (n = 840); PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PROMIS PF: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global-10 physical function; Neuro-QoL: Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders; UE: Upper extremity; LE: Lower extremity

Figure 2 – Correlation Plot of PROMs and Neuroperformance Tests.

The correlation plot of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and Neuroperformance Tests (NPTs) presents Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for each PROM-NPT relationship in the imputed dataset (n = 976). An “X” over a correlation coefficient indicates that it is not significant at p = 0.001. The scale on the right side of the figure indicates the strength of the correlation. PST: Processing speed test (n = 840); CST: Contrast sensitivity test (n = 476); MDT: Manual dexterity test (dominant hand) (n = 880); WST: Walking speed test (n = 840); PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PROMIS: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global-10 physical function; Neuro-QoL: Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders; Upper Ext: Upper extremity; Lower Ext: Lower extremity.

CST was weakly but significantly associated with all PROMs (p<0.001), except PROMIS-10 physical health. CST correlated with PDDS (rho = −0.31, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.23), Neuro-QoL UE (rho = 0.33, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.41), and Neuro-QoL LE (rho = 0.36, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.44).

Dominant hand MDT was significantly correlated with all PROMs, and had the strongest correlation with PDDS (rho = 0.53, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.58), Neuro-QoL UE (rho = −0.53, 95% CI −0.58 to −0.48), and Neuro-QoL LE (rho = −0.54, 95% CI −0.59 to −0.49). Similarly, non-dominant hand MDT had the strongest correlations with PDDS (rho = 0.55, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.59), Neuro-QoL UE (rho = −0.55, 95% CI −0.60 to −0.50), and Neuro-QoL LE (rho = −0.58, 95% CI −0.62 to −0.53), WST was significantly correlated with all physical disability PROMs, and had the strongest correlation with the PDDS (rho = 0.64, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.69) and Neuro-QoL LE (rho = −0.65, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.61).

3.1.3. Association of Neuroperformance Tests with Quantitative MRI Measures

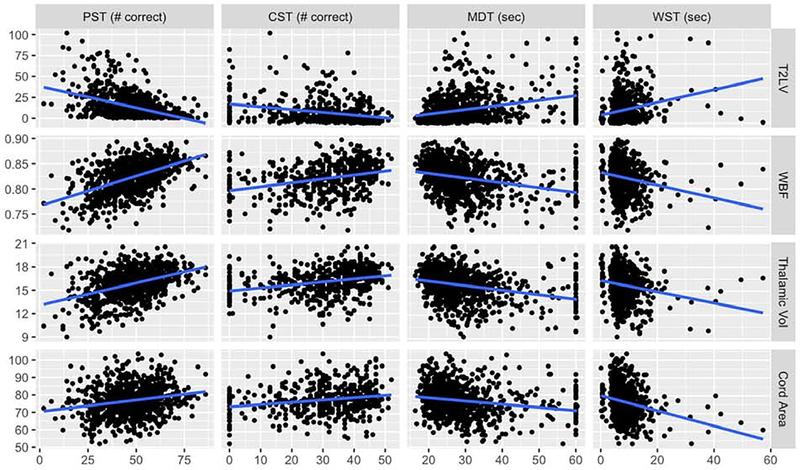

NPTs were evaluated for correlation with T2LV, WBF, TV, and CA (Figures 3 and 4). PST moderately correlated with T2LV (Spearman’s rho = −0.44, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.38) and WBF (rho = 0.49, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.54), and weakly correlated with TV (rho = 0.37, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.43).

Figure 3 – Scatterplot Matrix of Quantitative MRI Measures and Neuroperformance Tests.

Scatterplots for each quantitative MRI and Neuroperformance Test relationship are presented for the imputed sample (n = 976). The line represents a linear regression line for each relationship. PST: Processing speed test (n = 840); CST: Contrast sensitivity test (n = 476); MDT: Manual dexterity test (dominant hand) (n = 880); WST: Walking speed test (n = 840); T2LV: T2-weighted lesion volume (in mL); WBF: Whole brain fraction; Thalamic Vol: Thalamic volume (in mL); Cord Area: Cervical spinal cord cross-sectional area (in mm2).

Figure 4 –

Correlation Plot of Quantitative MRI Measures and Neuroperformance Tests The correlation plot of quantitative MRI measures and Neuroperformance Tests (NPTs) presents Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for each MRI-NPT relationship in the imputed dataset (n = 976). The scale on the right side of the figure indicates the strength of the correlation. PST: Processing speed test (n = 840); CST: Contrast sensitivity test (n = 476); MDT: Manual dexterity test (dominant hand) (n = 880); WST: Walking speed test (n = 840).

CST weakly correlated with T2LV (rho = −0.32, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.23), WBF (rho = 0.36, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.43), and TV (rho = 0.32, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.40).

Dominant hand MDT weakly correlated with T2LV (rho = 0.35, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.40), WBF (rho = −0.35, 95% CI −0.41 to −0.29), and TV (rho = −0.32, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.26). Non-dominant hand MDT weakly correlated with T2LV (rho = 0.34, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.40) and WBF (rho = −0.33, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.27), similar to dominant hand MDT.

WST weakly but significantly correlated with T2LV (rho = 0.23, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.30), WBF (rho = −0.24, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.17), and CA (rho = −0.25, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.19).

3.2. Linear Regression Modeling for Neuroperformance Tests

Final linear regression models for each NPT are presented in Table 3, along with their fully standardized regression coefficients. For a 1.0 increase in standard deviation of an independent variable, holding the other independent variables at their mean, the outcome (dependent variable) changes by the fully standardized coefficient number of standard deviations from its mean. Comparison of each final model to a model with all potential variables via ANOVA nested model comparisons demonstrated no significant differences in model performance (p>0.05). All variance inflation factors were <5, indicating no significant collinearity among independent variables.

Table 3–

Final Multivariate Linear Regression Models for each Neuroperformance Test (Imputed sample, n = 976)

| PSTa (n = 840) | CSTb (n = 476) | MDT (dominant hand)c (n = 880) | MDT (nondominant hand)c(n = 880) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.10) | -- | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) | -- |

| Age | -0.26 (−0.32, −0.20)* | -0.34 (−0.43, −0.26)* | -- | -- |

| Disease duration | -0.06 (−0.12, −0.01)* | -- | -- | -- |

| PDDS | -- | 0.12 (−0.001, 0.25) | -0.14 (−0.23, −0.05)* | -0.10 (−0.19, −0.02)* |

| PROMIS-10 physical | 0.08 (0.02, 0.13)* | -- | 0.06 (0.002, 0.12)* | -- |

| Neuro-QoL Upper Extremity | 0.15 (0.08, 0.23)* | 0.09 (−0.03, 0.20) | 0.25 (0.16, 0.33)* | 0.23 (0.15, 0.32)* |

| Neuro-QoL Lower Extremity | 0.13 (0.05, 0.22)* | 0.23 (0.08, 0.39)* | 0.11 (0.001, 0.23)* | 0.23 (0.12, 0.34)* |

| T2 Lesion Volume | −0.02 (−0.29, −0.16)* | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | −0.12 (−0.20, −0.05)* | −0.11 (−0.18, −0.05)* |

| Whole Brain Fraction | 0.15 (0.07, 0.22)* | -- | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | 0.13 (0.07, 0.19)* |

| Thalamic Volume | -- | 0.10 (−0.02, 0.20) | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.16) | -- |

| Cord Area | -- | 0.06 (−0.02, 0.14) | 0.06 (−0.003, 0.11) | 0.06 (0.0004, 0.11)* |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| Overall model F-test | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

PST: Processing Speed Test

CST: Contrast Sensitivity Test; Model with square of CST as outcome

MDT: Manual Dexterity Test; Model with inverse of MDT as outcome

WST: Walking Speed Test; Model with square root of WST as outcome

Fully standardized beta coefficients (95% CI) derived from an ordinary least squares linear regression method are reported for variables included in multivariate final model. For a 1.0 increase in standard deviation of an independent variable, holding the other independent variables at their mean, the outcome (dependent variable) changes by the fully standardized coefficient number of standard deviations from its mean.

“--” indicates exclusion of a variable from the final NPT model being described in that column

indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) of a variable in final multivariate model

The final model for PST included sex, age, disease duration, PROMIS-10 physical, Neuro-QoL UE, Neuro-QoL LE, T2LV, and WBF (adjusted R2 = 0.46). All terms were significant (p<0.05) except sex.

For CST, the model included age, PDDS, Neuro-QoL UE, Neuro-QoL LE, T2LV, TV, and CA (adjusted R2 = 0.30). Age and Neuro-QoL LE were significant terms (p<0.05).

For dominant hand MDT, the model included sex, PDDS, PROMIS-10 physical, Neuro-QoL UE, Neuro-QoL LE, T2LV, WBF, TV, and CA (adjusted R2 = 0.37). All terms were significant (p<0.05) except sex, TV, and CA. The model for non-dominant hand MDT differed slightly, as it included PDDS, Neuro-QoL UE, Neuro-QoL LE, T2LV, WBF, and CA (adjusted R2 = 0.40). All terms were significant (p<0.05).

The final model for WST included sex, age, disease duration, PDDS, PROMIS-10 physical, Neuro-QoL LE, T2LV, and CA (adjusted R2 = 0.40). All terms were significant (p<0.05) except age, disease duration, and PROMIS-10 physical health t-score.

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

Single imputation was performed for independent variables of interest based on known correlations with other variables. Patient characteristics were similar comparing the imputed and non-imputed datasets, including all variables of interest (Table 2). Correlations among NPTs and variables of interest were similar in the imputed and non-imputed datasets, but regression models varied slightly using complete cases (Supplementary Appendix).

Characteristics of patients in the overall dataset with any missing data (n = 700) were compared to those who had complete data (n = 297). Patients with incomplete data were older (44.9 versus 48.9 years, p<0.001), had longer disease duration (10.9 versus 13.0 years, p<0.001), and had higher self-reported disability (mean PDDS 1.5 versus 2.2, p<0.001). These observations also applied to the individual datasets created for each NPT, but were not as pronounced compared to the overall dataset. Patients with incomplete data had significantly worse performance on the PST, MDT, and WST (but not CST) compared to those with complete data.

The exclusion of patients with CIS or RIS yielded similar overall results (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The combination of multidomain NPTs, PROMs, and quantitative MRI provides a comprehensive assessment of MS disease status. In this large clinical cohort, we demonstrate that both PROMs indicating perceived physical impairment and quantitative MRI measures are moderately or weakly associated with impaired performance on all NPTs, particularly PST, MDT, and WST.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between individual and multidomain disability and MRI measures, but have been in smaller populations or were more limited evaluations. Impaired processing speed as measured by the SDMT or Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test has been correlated with whole brain volume (Rao et al., 2014), T2LV (Rao et al., 2014), and deep grey matter volume, specifically the thalamus (Bergsland et al., 2016; Bisecco et al., 2018; Debernard et al., 2015). Our results are in agreement with these findings, as T2LV, WBF, and TV had significant correlations and cross-sectional explanatory value for PST.

LCLA has previously been associated with T2LV (Chahin et al., 2015; Frohman et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2007), gray matter volume (Frohman et al., 2009), and whole brain atrophy (Balcer et al., 2017; Maghzi et al., 2014). The final MRI variables in our CST model were T2LV, TV, and CA. A direct association between LCLA and TV has not been reported, but one study established correlation between TV and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, a known correlate of visual disability in MS (Zivadinov et al., 2014). The correlation between CST and CA has not been reported, but may reflect collinearity of CA with other unmeasured markers of neurodegeneration.

In our study, the proportion of variance in CST explained by the covariates in a linear regression model was lower compared to that of other NPTs, but correlation coefficients for quantitative MRI measures were of similar magnitude.

Additionally, no MRI measures were significant despite their inclusion in the final CST model. This result may be explained by the fact that MRI measures included in this study do not reflect optic nerve pathology, which CST more directly captures (Balcer et al., 2017). Incorporation of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, as measured via optical coherence tomography, into a comprehensive routine assessment would likely better correlate with CST performance. We also observed weak correlations between CST and PROMs, which may be explained by inadequate capture of visual impairment in the PROMs utilized or noise/variability in the CST. Technical factors in early versions of CST could affect observed correlations, but recent updates have improved completion rates and data quality.

Manual dexterity, as measured by the 9HPT, has been weakly to moderately correlated with TV (Rasche et al., 2018), normalized brain volume (Daams et al., 2015; Rasche et al., 2018), and T2LV (Daams et al., 2015), consistent with our results. Interestingly, all four MRI metrics were retained in the linear model for dominant hand MDT (and three for non-dominant hand MDT) potentially reflective of the complex pathways involved in motor performance. Compared to CST and PST, the correlations with PROMs were highest in MDT and WST, likely indicative of the emphasis of physical disability in the selected PROMs.

T25FW has been associated with TV (Jakimovski et al., 2018; Motl et al., 2016; Nourbakhsh et al., 2016), T2LV (Jakimovski et al., 2018; Motl et al., 2016), and normalized brain volume (Jakimovski et al., 2018) in MS. A prior longitudinal study demonstrated that brain volume at baseline predicted changes in T25FW (Maghzi et al., 2014). Modest correlations were observed with these previously investigated MRI measures, but only T2LV and CA remained in the final linear model. Cervical spinal cord area is reported to predict overall disability as measured by the EDSS and MSFC (De Angelis, 2018), but one study reported weak correlation between CA and both MS Walking Scale and T25FW; partial correlation coefficients were −0.292 and −0.204, respectively, similar to our Spearman’s rho estimate of −0.25 for WST and CA (Daams et al., 2015).

This analysis utilized four PROMs reflective of mostly physical disability. PROMs intended to capture certain motor tasks were moderately correlated with their respective NPT. For example, WST had the strongest correlations with PDDS and Neuro-QoL LE, and both dominant and non-dominant hand MDT had moderate correlations with Neuro-QoL UE. Neuro-QoL UE and LE overall had moderate correlations with MDT and WST, but correlations were lower for PST and particularly CST. PROMIS-10 physical health t-score had weak correlations with NPTs, but was included in final models for PST, dominant hand MDT, and WST.

This study involves one of the largest clinical populations used for evaluating technology-enabled NPT and PROM capture in conjunction with quantitative MRI measures. The large sample size enables robust investigation regarding the associations of interest and establishes the utility of routinely capturing standardized comprehensive neurological assessments in a MS clinic population. Our study involves standardized, objective data collection in a real-world clinical setting, which is another relative strength. The combination of quantitative MRI and clinical data from a real-world clinical population is unique and has not, to our knowledge, been previously published.” The study also demonstrates that PROMs, objective neurological testing, and MRI measures provide additive explanatory value for physical disability in MS, supporting the need for comprehensive assessment. The results indicate that LE function, UE function, cognition, and vision are significantly associated with all quantitative MRI measures, but the strongest associations vary for each domain. The variation in the significant explanatory variables highlights the unique contribution of each MRI measure to complex domains of disability in MS. The modest proportion of variance explained by the final models for each NPT (adjusted R2 values of 0.30 to 0.46) may indicate that there are additional factors not measured by these NPTs that may contribute to physical disability. It is also important to note that NPTs, PROMs, and MRI metrics assess only partially overlapping aspects of MS.

One limitation of the current study is missing data, particularly for CST. Patients with incomplete data tended to be older with increased disability compared to those with complete information. Single imputation was performed, but did not result in significant alterations in the results. However, the missingness in these data raises an important point regarding comprehensive assessments. Fatigue and increased disability associated with older age and more advanced disease may impact a patient’s ability and stamina to complete extensive testing. In the case of CST, the lower completion rates could be attributed to technological aspects of the test related to facial recognition or high prevalence of visual impairment in our patient population. Moreover, patients who are more severely disabled may decline participation in these assessments, resulting in a potential selection bias for this study. Ongoing development and improvement of technology-based testing should evaluate usability in different age groups and patients with varying disability levels.

A second limitation is the cross-sectional design. As a result, temporal and causal relationships of the outcomes cannot be established. Cross-sectional associations can be informative in this setting, as learning which measures correlate with each other is of interest on a neurobiological level, particularly when these observations form the basis for longitudinal data analysis. Prior studies have demonstrated that ongoing brain volume loss is associated with worsening disability (Fisher et al., 2000) and longitudinal studies in this cohort to establish whether these measures change together over time would be beneficial. Such information could aid in establishing associations and potential predictive abilities of these measures for neurological decline.

Overall, these results demonstrate the utility of comprehensive quantitative assessment of MS disease status to better understand relationships among objectively measured disability, patient self-reported disability, and structural brain changes in a large clinical population. This examination of group statistics serves as the basis for future longitudinal analyses for application at the individual level. Further work is needed to determine clinically meaningful thresholds within each measure to aid in clinical decision-making. Comprehensive quantitative assessment enables clinicians to better detect disease worsening and determine responses to treatment, allowing more precise clinical care. Moreover, these data are conducive to completion of large, robust observational studies, particularly given the increasing emphasis on real-world data by the scientific community and regulatory agencies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Technology enables objective and standardized patient assessments in clinic

Patient-reported outcome measures and MRI correlated with neuroperformance scores

The strongest clinical and MRI predictors of neuroperformance test results varied

These tests have possible additive value in assessing multiple sclerosis disability

Acknowledgements

Dr. Laura Baldassari receives funding via National Multiple Sclerosis Society Sylvia Lawry Physician Fellowship Grant (#FP-1606-24540).

During the conduct of this study, Dr. Brandon Moss received fellowship funding via a National Multiple Sclerosis Society Institutional Clinician Training Award (ICT 0002).

Dr. Gabrielle Macaron receives fellowship funding via a National Multiple Sclerosis Society Institutional Clinician Training Award (ICT 0002).

During the conduct of this study, Dr. Marisa McGinley received funding via National Multiple Sclerosis Society Sylvia Lawry Physician Fellowship Grant (#FP-1506-04742).

Study Funding/Sponsorship

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The technology discussed (Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test, MSPT) was developed and implemented at the Cleveland Clinic in partnership with Biogen. Biogen did not have involvement in study design, data analysis or interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Declarations of Interest

Dr. Laura Baldassari has received personal fees for serving on a scientific advisory board for Teva.

Dr. Kunio Nakamura has received personal fees for consulting from NeuroRx Research, speaking from Sanofi Genzyme, and license from Biogen Idec. He has received research support from NIH NINDS, NMSS, DOD, Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, and Novartis.

Dr. Brandon Moss reports personal compensation for consulting for Genentech and speaking for Genzyme.

Dr. Gabrielle Macaron has served on an advisory board for Genentech. She receives fellowship funding from Biogen (#6873-P-FEL).

Ms. Hong Li: No declarations of interest.

Ms. Malory Weber: No declarations of interest.

Dr. Stephen Jones has received travel and speaking fees from Siemens and IMRIS, speaking fees from Radnet and Saint Judes, research support and travel fees from MS PATHS, and research support from the NIH.

Dr. Stephen Rao has received honoraria, royalties or consulting fees from Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis, American Psychological Association, International Neuropsychological Society and research funding from the National Institutes of Health, US Department of Defense, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, CHDI Foundation, Biogen, and Novartis. He contributed to intellectual property that is a part of the MSPT, for which he has the potential to receive royalties.

Dr. Deborah Miller has contributed to intellectual property that is a part of the MSPT, for which she has the potential to receive royalties.

Dr. Devon Conway has received research support paid to his institution from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and Novartis Pharmaceuticals. He has received personal consulting fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Tanabe Laboratories.

Dr. Robert Bermel has served as a consultant for Biogen, Genzyme/Sanofi, Genentech/Roche, and Novartis. He receives research support from Biogen and Genentech, and contributed to intellectual property that is a part of the MSPT, for which he has the potential to receive royalties.

Dr. Jeffrey Cohen has received personal fees for consulting for Convelo, Population Council; speaking for Mylan; and serving as an Editor of Multiple Sclerosis Journal.

Dr. Daniel Ontaneda has received research support from National Multiple Sclerosis Society, National Institutes of Health, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Race to Erase MS Foundation, Genentech, and Genzyme. He has also received consulting fees from Biogen, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme, Novartis, and Merck.

Dr. Marisa McGinley has served on scientific advisory boards for Genzyme and Genentech.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balcer LJ, Baier ML, Cohen JA, Kooijmans MF, Sandrock AW, Nano-Schiavi ML, Pfohl DC, Mills M, Bowen J, Ford C, Heidenreich FR, Jacobs DA, Markowitz CE, Stuart WH, Ying GS, Galetta SL, Maguire MG, Cutter GR, 2003. Contrast letter acuity as a visual component for the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite. Neurology 61(10), 1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcer LJ, Raynowska J, Nolan R, Galetta SL, Kapoor R, Benedict R, Phillips G, LaRocca N, Hudson L, Rudick R, 2017. Validity of low-contrast letter acuity as a visual performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 23(5), 734–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsland N, Zivadinov R, Dwyer MG, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict RH, 2016. Localized atrophy of the thalamus and slowed cognitive processing speed in MS patients. Mult Scler 22(10), 1327–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisecco A, Stamenova S, Caiazzo G, d’Ambrosio A, Sacco R, Docimo R, Esposito S, Cirillo M, Esposito F, Bonavita S, Tedeschi G, Gallo A, 2018. Attention and processing speed performance in multiple sclerosis is mostly related to thalamic volume. Brain imaging and behavior 12(1), 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahin S, Balcer LJ, Miller DM, Zhang A, Galetta SL, 2015. Vision in a phase 3 trial of natalizumab for multiple sclerosis: relation to disability and quality of life. J Neuroophthalmol 35(1), 6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daams M, Steenwijk MD, Wattjes MP, Geurts JJ, Uitdehaag BM, Tewarie PK, Balk LJ, Pouwels PJ, Killestein J, Barkhof F, 2015. Unraveling the neuroimaging predictors for motor dysfunction in long-standing multiple sclerosis. Neurology 85(3), 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis FS,J; Eshaghi A; Garcia A; Prados F; Plantone D; Doshi A; John N; Calvi A; MacManus D; Ourselin S; Pavitt S; Giovannoni G; Parker R; Weir C; Stallard N; Hawkins C; Sharrack B; Connick P; Chandran S; Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott C; Barkhof F; Chataway J, 2018. Spinal cord area is a stronger predictor of physical disability than brain volume in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (O113), European Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho M, Marques F, 2012. Jackknife Euclidean Likelihood-Based Inference for Spearman’s Rho. North American Actuarial Journal 16, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Debernard L, Melzer TR, Alla S, Eagle J, Van Stockum S, Graham C, Osborne JR, Dalrymple-Alford JC, Miller DH, Mason DF, 2015. Deep grey matter MRI abnormalities and cognitive function in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Psychiatry research 234(3), 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JS, Rudick RA, Cutter GR, Reingold SC, 1999. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite Measure (MSFC): an integrated approach to MS clinical outcome assessment. National MS Society Clinical Outcomes Assessment Task Force. Mult Scler 5(4), 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E, Rudick RA, Cutter G, Baier M, Miller D, Weinstock-Guttman B, Mass MK, Dougherty DS, Simonian NA, 2000. Relationship between brain atrophy and disability: an 8-year follow-up study of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 6(6), 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman EM, Dwyer MG, Frohman T, Cox JL, Salter A, Greenberg BM, Hussein S, Conger A, Calabresi P, Balcer LJ, Zivadinov R, 2009. Relationship of optic nerve and brain conventional and non-conventional MRI measures and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, as assessed by OCT and GDx: a pilot study. Journal of the neurological sciences 282(1–2), 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon RC, Lai JS, Bode R, Choi S, Moy C, Bleck T, Miller D, Peterman A, Cella D, 2012. Neuro-QOL: quality of life item banks for adults with neurological disorders: item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population testing. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 21(3), 475–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthMeasures, 2018. PROMIS. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis. (Accessed August 1 2018).

- Jakimovski D, Weinstock-Guttman B, Hagemeier J, Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Gandhi S, Bennett SE, Fuchs TA, Bergsland N, Dwyer MG, Benedict RHB, Zivadinov R, 2018. Walking disability measures in multiple sclerosis patients: Correlations with MRI-derived global and microstructural damage. Journal of the neurological sciences 393, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, 2001. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine 16(9), 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Pula JH, Cadavid D, 2013. Validation of patient determined disease steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC neurology 13, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghzi AH, Revirajan N, Julian LJ, Spain R, Mowry EM, Liu S, Jin C, Green AJ, McCulloch CE, Pelletier D, Waubant E, 2014. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of clinical outcomes in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 3(6), 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, Otero-Romero S, Amato MP, Chandraratna D, Clanet M, Comi G, Derfuss T, Fazekas F, Hartung HP, Havrdova E, Hemmer B, Kappos L, Liblau R, Lubetzki C, Marcus E, Miller DH, Olsson T, Pilling S, Selmaj K, Siva A, Sorensen PS, Sormani MP, Thalheim C, Wiendl H, Zipp F, 2018. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. European journal of neurology 25(2), 215–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motl RW, Zivadinov R, Bergsland N, Benedict RH, 2016. Thalamus volume and ambulation in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Neurodegenerative disease management 6(1), 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourbakhsh B, Azevedo C, Maghzi AH, Spain R, Pelletier D, Waubant E, 2016. Subcortical grey matter volumes predict subsequent walking function in early multiple sclerosis. Journal of the neurological sciences 366, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontaneda D, LaRocca N, Coetzee T, Rudick R, 2012. Revisiting the multiple sclerosis functional composite: proceedings from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) Task Force on Clinical Disability Measures. Mult Scler 18(8), 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C, 2015. Quality improvement in neurology: Multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary. Neurology 85(21), 1904–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Losinski G, Mourany L, Schindler D, Mamone B, Reece C, Kemeny D, Narayanan S, Miller DM, Bethoux F, Bermel RA, Rudick R, Alberts J, 2017. Processing speed test: Validation of a self-administered, iPad((R))-based tool for screening cognitive dysfunction in a clinic setting. Mult Scler 23(14), 1929–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Martin AL, Huelin R, Wissinger E, Khankhel Z, Kim E, Fahrbach K, 2014. Correlations between MRI and Information Processing Speed in MS: A Meta-Analysis. Multiple sclerosis international 2014, 975803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasche L, Scheel M, Otte K, Althoff P, van Vuuren AB, Giess RM, Kuchling J, Bellmann-Strobl J, Ruprecht K, Paul F, Brandt AU, Schmitz-Hubsch T, 2018. MRI Markers and Functional Performance in Patients With CIS and MS: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Neurol 9, 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JK, Schindler D, Rao SM, Venegas F, Bruzik ET, Gabel W, Williams JR, Phillips GA, Mullen CC, Freiburger JL, Mourany L, Reece C, Miller DM, Bethoux F, Bermel RA, Krupp LB, Mowry EM, Alberts J, Rudick RA, 2019. Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test: Technical Development and Usability. Advances in therapy 36(7), 1741–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudick RA, Miller D, Bethoux F, Rao SM, Lee JC, Stough D, Reece C, Schindler D, Mamone B, Alberts J, 2014. The Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test (MSPT): an iPad-based disability assessment tool. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE(88), e51318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GF, Schwartz ED, Lei T, Souza A, Mishra S, Jacobs DA, Markowitz CE, Galetta SL, Nano-Schiavi ML, Desiderio LM, Cutter GR, Calabresi PA, Udupa JK, Balcer LJ, 2007. Relation of vision to global and regional brain MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 69(23), 2128–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinov R, Bergsland N, Cappellani R, Hagemeier J, Melia R, Carl E, Dwyer MG, Lincoff N, Weinstock-Guttman B, Ramanathan M, 2014. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and thalamus pathology in multiple sclerosis patients. European journal of neurology 21(8), 1137–e1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared with qualified investigators by request from the corresponding author for purposes of replicating procedures and results.