Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite the importance of using penile injections as part of a penile rehabilitation program, men have difficulty complying with these programs.

AIM:

To test a novel psychological intervention based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT-ED) to help men utilize penile injections.

METHODS:

This pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) recruited men who were starting a structured penile rehabilitation program (Standard Care (SC)) following radical prostatectomy. SC instructed patients to use penile injections 2–3 times/week. Participants were randomized to the SC+ACT-ED or SC+Enhanced Monitoring (EM). Over four months, those in SC+ACT-ED received SC plus four ACT sessions and three ACT phone calls, those in SC+EM received SC plus seven phone calls from an experienced sexual medicine nurse practitioner. Participants were assessed at study entry, four and eight months. For this pilot study the goal was to determine initial effectiveness (i.e., effect sizes: d=0.2, small; d=0.5, medium; and d=0.8, large).

OUTCOMES:

Primary outcomes were feasibility and use of penile injections. Secondary outcomes were ED treatment satisfaction (EDITS), sexual self-esteem and relationship quality (SEAR), sexual bother (SB), and prostate cancer treatment regret.

RESULTS:

53 participants were randomized (ACT, n=26; EM, n=27). The study acceptance rate was 61%. At four months, the ACT-ED group utilized more penile injections/week (1.7) compared to the EM group (0.9, d=1.25, p=0.001), and was more adherent to penile rehabilitation compared to the EM (ACT, 44%; EM, 10%, RR=4.4, p=0.02). These gains were maintained at eight months for injections/week (ACT=1.2; EM=0.7, d=1.08, p=0.03), while approaching significance for adherence (18%; EM, 0%, p=0.10). At four months, ACT-ED, compared to EM, reported moderate effects for greater satisfaction with ED treatment (d=0.41, p=0.22), greater sexual self-esteem (d=0.54, p=0.07) and sexual confidence (d=0.48, p=0.07), lower sexual bother (d=0.43, p=0.17), and lower prostate cancer treatment regret (d=0.74, p=0.02). At the eight months, moderate effects in favor of ACT-ED were maintained for greater sexual self-esteem (d=0.40, p=0.19) and less treatment regret (d=0.47, p=0.16).

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS:

ACT concepts may help men utilize penile injections and cope with the effects of ED.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS:

Strengths: innovative intervention utilizing ACT concepts and pilot RCT. Limitations: the pilot nature of the study (e.g., small samples size and lack of statistical power).

CONCLUSION:

ACT-ED is feasible and significantly increases the use of penile injections. ACT-ED also shows promise (moderate effects) for increasing satisfaction with penile injections and sexual self-esteem while decreasing sexual bother and prostate cancer treatment regret.

Keywords: prostate cancer, erectile dysfunction, sexual function, erectile rehabilitation

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, with over 160,000 new cases diagnosed yearly (1). A primary side effect of prostate cancer treatment is erectile dysfunction (ED), with as many as 85% of men reporting problems with erections even up to six years post-treatment (2, 3). ED can have important quality of life implications, as men with ED report significant frustration, increased depressive symptoms, and reduced general happiness with life (4, 5). ED can also lead to relationship stress, a reduction in intimacy, and sexual dysfunction in female partners (6).

Radical prostatectomy is one of the gold standard treatments for early stage prostate cancer, and the field has made important advances in treating ED following surgery. Many centers practice the concept of “penile rehabilitation.” Since cavernous nerves responsible for erections may take up to 24 months to recover following surgery, penile rehabilitation programs often advise men to achieve medication-assisted erections during this recovery period. Although penile rehabilitation has been debated, the concept is that regular erectile activity helps preserve penile tissue and increase the chance of recovering erections when nerve recovery has occurred (8). Oral medications (e.g., Viagra, Cialis, and Levitra) are generally ineffective in helping produce an erection early in this recovery period as they rely on nitric oxide secreted from healthy nerves. Penile injections are the most effective ED treatment option and are the cornerstone of many penile rehabilitation programs (8).

Despite the potential importance of penile rehabilitation, men have difficulty complying with these programs. The majority of men with prostate cancer (50–80%) discontinue the use of medical interventions for ED (pills, penile injections, vacuum devices) within one year of initiating this treatment (9–13). In a sample of men with prostate and bladder cancer, only 54% continued with penile injections after four months of use, and of those, only 45% were using the injections at the recommended rate of two to three times per week suggested for rehabilitation (13). Many barriers to compliance with ED treatments and penile rehabilitation programs are psychological. Many men find themselves in a “Cycle of Avoidance” related to the use of ED treatments (14). This cycle starts with anxiety, frustration, and disappointment related to ED which often leads to avoidance of sexual situations and avoidance of the use of ED treatments (15). Unfortunately, the difficulty with sustaining rehabilitation can negatively impact men’s chances of recovering erections following radical prostatectomy.

A novel coaching/psychological intervention was designed to increase adherence to an erectile rehabilitation program. Informed by past qualitative work, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (16, 17) was used as the therapeutic framework to help men reduce avoidance to using penile injections. Our intervention helped men focus on their values related to erectile functioning, accept the frustration related to ED and using penile injections, develop a sense of willingness to use injections while experiencing these frustrations, identify and overcome barriers, and commit to a penile rehabilitation program. While there is a current literature of psycho-educational interventions which have demonstrated effectiveness in improving men’s sexual functioning following prostate cancer treatment, these interventions have generally not focused specifically on penile rehabilitation (18–22). Our intervention builds on the work of these previous interventions, while exploring novel and important theoretical and clinical components. Specifically, this intervention includes a conceptual framework for avoidance of ED treatments, outlines how this avoidance leads to poor compliance, and utilizes ACT therapeutic elements which shift the focus of this intervention from the psycho-educational to reducing avoidance of ED treatments. It was hypothesized that this pilot RCT would indicate that the ACT intervention is feasible and demonstrate initial effectiveness in increasing the use of penile injections. It was also hypothesized the ACT intervention would positively impact secondary psychosocial variables of satisfaction with injections, sexual self-esteem, sexual bother, and prostate cancer treatment regret.

Methods

Study Design

This was a pilot randomized controlled study; participants were recruited by trained research staff from the Sexual Medicine Program. Participants were randomized 1:1 to a standard care penile rehabilitation program (SC) plus the ACT intervention (ACT-ED, N=26) or SC plus an Enhanced Monitoring intervention (EM, N=27). The study interventions (ACT-ED and EM) lasted approximately four months. The study assessments were completed at baseline (i.e., before participants were informed of their randomized assignment), at four months and at eight months following baseline. The four-month assessment was administered upon completion of the assigned intervention.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size projection for this pilot RCT study was 60 subjects. This was based on sample sizes of previous pilot studies in this area (23, 24) as well as the practicality of running the study within the funding period. A priori, we considered this sample size large enough to demonstrate feasibility and initial effectiveness (reliable Cohen’s d effects sizes) of the ACT intervention to use to power a larger study. We did not consider this sample size large enough to provide the power needed to consistently demonstrate statistical significance. To illustrate, with the sample size of 60 subjects (assuming dropout rate of 33%), a large effect size (Cohen’s d) (25) of 0.88 would be needed for 80% power (two-sided significance level of 0.05) to detect between-group difference for the mean number of injections per week (13). We did not expect the effects for the intervention to consistently reach the needed large effect of d=0.88 to demonstrate significance. As a result, we will report both Cohen’s d effects sizes and statistical significance.

Patient Population

The participant pool consisted of men who had undergone a radical prostatectomy (open or robotic) and met the following eligibility criteria: 1) were within 9 months of radical prostatectomy; 2) had good erectile functioning pre-surgery (i.e., 24 or greater on Erectile Function Domain (EFD) of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) (26); 3) were seen at the our center’s Sexual Medicine Program; and 4) were advised by the clinical staff to start penile injections as part of penile rehabilitation. The exclusion criteria included: 1) specific injection phobia; 2) a history of bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder; and 3) a current diagnosis of major depression that would preclude from giving informed consent or being an active participant in a therapeutic session. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, complied with the ICH Good Clinical Practice Guidelines founded on the Declaration of Helsinki, and subjects provided informed consent (Clinical trial #: NCT01275404).

Interventions

Standard Care (SC):

At the initial visit to the Sexual Medicine Program (approximately 6 to 24 weeks post-surgery), the clinical staff explained the concept of penile rehabilitation and assessed the patient’s success with oral medication (PED5 inhibitors). If oral medication did not produce an erection firm enough for penetration, the patient was instructed to start penile injections. The penile injection training was provided by a nurse practitioner (NP) over two visits approximately one week apart. These visits started within one or two weeks following the initial visit to the Sexual Medicine Program. Both training visits lasted approximately one hour and were used for teaching purposes and to titrate the dose of the medication. Since it usually takes a number of injections at home to determine the optimal dose, the patients were asked to call the NP after initial in-home injection attempts to adjust dosing. These calls continued until the dose was deemed appropriate. Lastly, follow-up visits were scheduled every four months to monitor progress.

Arm 1: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Erectile Dysfunction (ACT-ED):

This intervention adapted the ACT framework (16) and concepts to help adherence to the standard care erectile rehabilitation program. A clinical psychologist delivered the ACT-ED intervention and special attention was given to fully integrate ACT-ED into the rehabilitation process. The ACT-ED arm consisted of seven therapeutic contacts: two 30–45 minute in-person meetings held the same day as the two injection training sessions, one 15–30 minute phone session one week following the second in-person session, and three brief (5–10 minutes) phone calls which began two weeks apart. The time between phone calls progressively increased by a week until the phone calls were four weeks apart. The last ACT-ED contact was an in-person meeting (15–30 minutes) at the four-month SC follow-up visit (See Table 1 for timing of sessions). The ACT concepts utilized in our intervention were: 1) Defining Values, 2) Acceptance and Willingness, 3) Experiential Exposure, and 4) Commitment. Table 1 describes the session titles, content, and active ACT ingredients for each session.

Table 1:

ACT-ED Session Content and Timing

| Session Title | General Tasks | ACT Principles & Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: The Fork in the Road- The Choice of a Vital Life: An Introduction to ACT-ED | 1. Introduction to treatment & review of treatment time line and goals 2. Psycho-education on side effects and recovery after radical prostatectomy 3. Emphasis on the benefits of adherence to sexual medicine protocol 4. Introduction to erectile dysfunction (ED) and potential impact |

1. Introduce core concepts of ACT-ED: “The Acceptance and Commitment Cycle & Avoidance Cycle” 2. Acceptance and commitment are more effective strategies than avoidance and control to reduce distress. 3. Goal to decrease avoidance of and engage in activities related to penile rehabilitation regardless of discomfort or distress 4. Sexual Values Assessment 5. Conceptualize recovery in terms of maintaining valued activities and goals |

| Session 2: It’s Your Life: Story of Recovery and Making a Commitment | 1. Update on injection therapy training and reactions 2. Review current side effects of urinary incontinence and ED 3. Injection Therapy: Discuss behavior aspects to help in use of injections |

1. Articulate Story around ED & recovery 2. Discuss psychological impact of ED 3. How negative thinking impairs ability to move forward towards goals 4. Integration into Sexual Activity/Intimate Relationship 5. Barriers Assessment: Identify potential barriers and obstacles that might get in the way of acting consistently with these values 6. Fork in the Road Handout: Living a valued life vs. living a life in avoidance 7. Life Bus Handout: Having a thought vs. buying a thought: Cognitive Defusion 8. Make a commitment to taking purposeful action step |

| Session 3 (2 weeks post Session 2): Get Out of Your Mind Get into Your… Acceptance, Willingness and Mindfulness | 1. Update on injection therapy training and reactions 2. Verbal Bullseye Exercise: How many times a week have you injected? 3. Introduce and explain Injection Log |

1. Acceptance and willingness vs. avoidance and control 2. Acceptance of what cannot be changed (thoughts and feelings) and changing what can be changed. 3. Discuss concept of “willfulness” 4. Self-Awareness (Mindfulness) a. Applications to injection therapy and sexual intimacy |

| Phone Sessions (4, 6, & 9 weeks post session 2): How Do We Keep It Up! Monitoring our Progress and Maintaining Valued Actions and Goals | 1. Update on injection use and quality of erections. 2. What is the patient’s “story” around recovery now? 3. Review Injection Log 4. Review progress with sexual functioning |

1. Review patient’s values related to sexual functioning, Acceptance, Willingness & Diffusion 2. Importance of persistence 3. Commit to moving in directions consistent with goals |

| Session 4 (13 weeks post session 2): Just Do It! Taking Effective Action | 1. Update on injection use and quality of erections. 2. What is the patient’s “story” around recovery now? 3. Review Injection Log 4. What are the current obstacles and barriers 5. Strategies to address ongoing barriers 6. Discussion of future expectations and fears |

1. Review core concepts of ACT-ED: “The Acceptance Cycle & Avoidance Cycle” 2. Use of acceptance training to address difficult thoughts and feelings about erectile dysfunction a. Focus on the ability to act in a valued direction while maintaining awareness of difficult experiences. b. Mindfulness applications to sexual intimacy 3. Review long term goals and “Fork in the road” diagram 4. Remake a commitment to treatment and adherence to injection therapy protocol and achieving identified goals |

Arm 2: Enhanced Monitoring (EM):

The EM arm consisted of seven phone contacts (5–15 minutes) delivered on the same time schedule as ACT-ED contacts. A nurse practitioner (NP) with over six years of experience with sexual medicine delivered the EM arm. The structure of the EM contacts was the same for all seven contacts. The NP asked questions about the patient’s progress with the erectile rehabilitation program, managed technical issues related to injections, and answered patients’ questions related to erectile rehabilitation. EM is an extension of SC and served as a control for information and monitoring.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned using a stratified block design into either the intervention condition (ACT-ED) or the control condition (EM). Participants were randomly allocated to the two treatment arms using a permuted block randomization procedure to ensure that the two treatment groups would be balanced with the respective type of surgery (open and robotic). All consented subjects were registered with our institution’s Protocol Participant Registration (PPR) system and randomized using our institution’s Clinical Research Database (CRDB). Randomization was overseen by our Biostatistics Service.

Blinding

All study patient reported outcomes were completed online to reduce any potential influence from research staff. Since informed consent procedures explained the two different study arms, participants were not blinded to their treatment condition. However, since both treatment conditions were added to SC, all subjects knew they were receiving an intervention that could assist with their compliance to the rehabilitation program. Additionally, the research staff who reminded subjects to complete study measures online were not blinded to study condition.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this pilot RCT was first to assess preliminary intervention feasibility. Feasibility was assessed in multiple ways including the acceptance rate, defined as the percentage of eligible individuals who were recruited to the study. A goal of 40% acceptance rate was set based on previous studies in this area (27, 28). Second, the benchmark for retention and assessment was 50%, such that if 50% of participants complete all sessions and all assessments then study feasibility will be demonstrated, with comparison of attrition between the two study arms.

The primary efficacy outcome for this pilot RCT was penile injection use. Participants brought their unused syringes to the four and eight-month Sexual Medicine Program visits. The prescriptions for the penile injection medication included a standard number of syringes and therefore, the injections used between assessment periods totaled the number of prescribed syringes minus the unused syringes. This process is similar to pill counts and is considered an objective measure of injection use (29, 30). If participants did not attend their four or eight-month visit, efforts were made to contact the participant by phone.

Secondary study outcomes included several self-report measures assessing a range of important constructs. These assessments were completed online through the intuition’s secure platform. The satisfaction of using penile injections was assessed with the Erectile Dysfunction Inventory of Treatment Satisfaction (EDITS (31)), an 11-item questionnaire designed to assess the patient’s satisfaction with medical treatments for ED. Sexual self-esteem and confidence was measured with the Sexual Self-Esteem and Relationship Questionnaire (SEAR(32)), a 12-item measure that assesses sexual relationship satisfaction, sexual self-esteem, and overall relationship satisfaction [31]. Sexual bother was assessed using the Sexual Bother (SB) 3-question subscale of the Prostate-Health Related QOL (PHR-QOL) questionnaire (33). Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Revised (CESD-R) scale, a 20-item measure that assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week (34). Participants also completed the Prostate Cancer Treatment Regret Scale (PCTR), a 5-item scale that asks participants to reflect on their decision of selecting surgery as their treatment for prostate cancer (35).

Additionally, the Erectile Function Domain (EFD) of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) (26) was used to assess erectile function. The Erectile Function Domain is a 6-item subscale of the IIEF. The EFD score was used to assess response to penile injections to ensure both groups were achieving a quality response to injections. This was not considered as an outcome variable since erectile function recovery may take at least 24-month post-surgery and the average time of follow-up for this pilot study was 12 months post-surgery.

Lastly, general demographic variables were collected to describe the study. Data on participants’ nerve sparing procedure and a nerve sparing score was also documented. At our institution, surgeons rate the degree of nerve sparing using a nerve sparing grading system where neurovascular bundle (NVB) preservation (on each side) is scored individually on a 1–4 scale: 1 - complete preservation, 2 - near complete preservation, 3 - partial resection, 4 - complete resection. The two scores are added together (range=2–8), lower scores indicating greater preservation and a score of 2 (1 and 1 bilaterally) indicating complete nerve sparing/preservation surgery.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to report the demographic variables. Percentages were used to assess feasibility criteria, and Chi-square was used to compare completion rates between groups. When considering the outcome variables, given the pilot nature of the data, the study was not powered to determine significant differences between groups but was powered to determine feasibility and initial effectiveness (i.e., effect sizes). As such, both significance levels and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported. Cohen’s guide for interpreting effect sizes is: d=0.2, small; d=0.5, medium; and d=0.8, large effect. The syringe count data was used to calculate the average number of injections per week. ANCOVA was used to identify between-group differences in the primary outcome of mean number of injections per week and the secondary outcome variables. Group assignment and scores at baseline were used to predict four and eight-month scores. Chi-square tests were used to compare between groups the percent of men compliant with penile rehabilitation. Adherence was defined as at least two injections per week for three out of four weeks in a month (i.e., a total of at least 24 injections of a four-month period).

Results

Study Sample

Table 2 outlines the baseline characteristics for both groups. Participants were recruited from May 2011 to February 2013. The average age of the sample was 60 years old (SD = 7.3). The majority of participants were White 80% (n=42), and 19% (n=10) were Black. The majority of men were married or partnered 81% (n=43) and had a college or graduate degree (73%; n=39). Both groups showed a quality response to penile injections (EFD: ACT-ED, 23; EM, 24). There were no significant differences between the two groups on any baseline demographic characteristics, except the EM group appeared to have a qualitatively higher percentage of participants who were married (see Table 2). The other difference between groups was in nerve sparing; the EM group had significantly better nerve preservation at baseline indicated by mean nerve sparing scores (ACT-ED, 3.6; EM, 2.9, p = 0.04, lower scores indicated greater nerve preservation) and the EM group had a higher percentage of complete nerve sparing/preservation surgery indicated by a nerve sparing score of 2 (ACT-ED, 25%; EM, 60%, p = 0.02).

Table 2:

Subject Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | Total | ACT-ED | EM | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 53 | 26 | 27 | |

| Mean Age | 60 (SD = 7.3) | 60 (SD = 7.5) | 61 (SD = 7.1) | 0.55 |

| Race | ||||

| - White | 80% | 83% | 77% | 0.40 |

| - Black | 19% | 17% | 20% | |

| - “Other” | 1% | 0% | 3% | |

| Married | 81% | 73% | 90% | 0.14 |

| College Degree or Higher | 73% | 77% | 69% | 0.85 |

| Months Post-Surgery | ||||

| - Baseline | 4.1 (SD = 2.5) | 4.0 (SD = 2.2) | 4.2 (SD = 2.7) | 0.75 |

| - End of Study | ||||

| Erectile Function Domain with Injections | 23 (SD = 8.5) | 23 (SD = 8.7) | 24 (SD = 8.4) | 0.61 |

| Nerve Sparing | ||||

| - Mean Score | 2.3 (SD = 1.2) | 3.6 (SD = 1.1) | 2.9 (SD = 1.2) | 0.04 |

| - Complete Nerve Sparing | 44% | 25% | 60% | 0.02 |

Feasibility

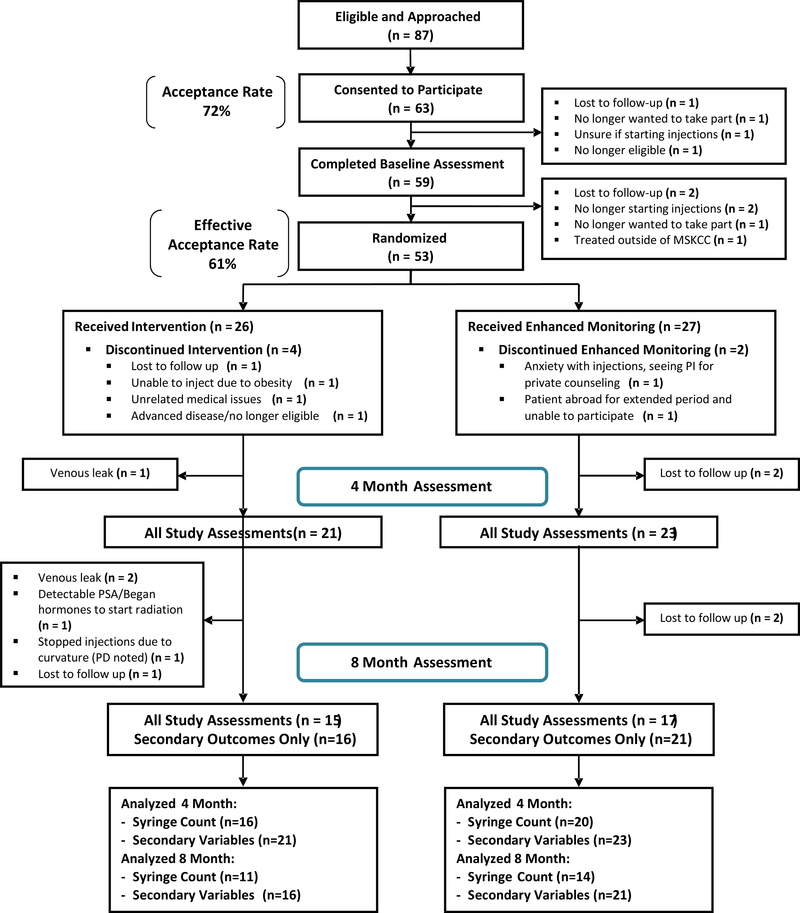

One primary aim was to investigate the feasibility of the intervention by assessing the acceptance rates, intervention completion rates, and study completion rates between both arms (detailed in Figure 1). The results indicate that the a priori goal of a 40% acceptance rate was achieved. The initial acceptance rate was 72% (63 randomized out of 87 approached), and the effective acceptance rate was 61% (53 subjects who started either intervention out of 87 approached). The a priori goal for completion rate was 50% aggregated over both arms, and again, the study surpassed this threshold. For both arms, 89% (n = 47) completed the interventions (ACT, 85%, n = 22; EM, 93%, n = 25, p=0.36), 83% (n = 44) completed all four-month study assessments (ACT, 81%, n = 21; EM, 85%, n = 23, p = 0.67), and 60% (n = 32) completed all eight-month assessments (ACT, 57%, n = 15; EM, 61%, n = 17, p = 0.69).

Figure 1:

CONSORT Diagram

Note: “All Study Assessments” includes syringe count and secondary outcomes. Eight subjects (ACT: 5; EM, 3) were removed from the syringe count analysis since they responded to PED5i during the study.

Frequency of Penile Injection Use

When calculating the frequency of penile injection use, eight men recovered a response to PDE5i during the study period were excluded for this frequency of injection analysis. This decision was made because from a rehabilitation perspective, once men respond to a PDE5i, they are no longer required to use penile injections. Five men responded to a PDE5i in the ACT-ED group, while three men responded to a PDE5i in the EM group. At the four-month assessment (i.e., four months after baseline, upon completion of intervention; Table 3), the ACT-ED group reported greater mean weekly injection use compared to the EM group (1.7 injections/week versus 0.9, d = 1.25, p = 0.001), and greater adherence to injection use (44% of men adherent versus 10% of men adherent, p = 0.02, Relative Risk (RR) = 4.4).

Table 3:

Four Month Injection Use

| Variable | ACT-ED | EM | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Weekly Injection Use | 1.7 (SD = 0.7) | 0.9 (SD = 0.4) | 0.001 | d = 1.25 |

| % of Men Adherent (≥ 2 x weekly) | 44% | 10% | 0.02 | RR = 4.4 |

Note: ACT, n = 16; EM, n = 20

At the eight-month assessment (i.e., four months after completion of intervention; Table 4), differences between the groups remained such that the ACT-ED group reported greater mean injection use compared to the EM group (1.2 versus 0.7, d = 1.08, p = 0.03), and an indication of greater adherence to injection use (18% versus 0%, p = 0.10). RR could not be calculated since the adherence for the EM group was zero.

Table 4:

Eight Month Injection Use

| Variable | ACT-ED | EM | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Weekly Injection Use | 1.2 (SD = 0.5) | 0.7(SD = 0.5) | 0.03 | d = 1.08 |

| % of Men Adherent (≥ 2 x eekly) | 18% | 0% | 0.10 | RR = NA |

Note: ACT, n = 11; EM, n = 14: RR could not be calculated since the adherence for the EM group was zero.

Secondary Outcomes

At the four-month assessment, the ACT-ED group (Table 5), as compared to the EM group, reported moderate effects for greater ED treatment satisfaction (EDITS; d = 0.41, p = 0.22), greater sexual self-esteem (SEAR; d = 0.54, p = 0.07,) lower sexual bother (SB); d = 0.43, p = 0.17), and lower prostate cancer treatment regret (PCTR); d = 0.74, p = 0.02). Effects were also seen for the subscales of the SEAR (see Table 5). There was no difference in depressive symptoms (CES-D). By the eight-month follow-up assessment (Table 6), effects in favor of the ACT-ED group were maintained for greater sexual self-esteem (d = 0.40, p = 0.19) and sexual relationship (d=0.52, p=0.10) and less prostate cancer treatment regret (d = 0.47, p = 0.16).

Table 5:

Secondary Outcomes Four Month Assessment

| Variable | ACT-ED Mean (SD) |

EM Mean (SD) |

Intervention Compared to Control |

p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Treatment Satisfaction (Range = 0–44) | 33.6 (6.5) | 29.8(10.8) | ↑ 3.8 points | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| Sexual Self-Esteem and Relationship Total (SEAR; Range = 0–100) | 70.3 (23.7) | 58.6 (19.8) | ↑ 11.7 points | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| - SEAR-Confidence (Range = 0–100) | 77.2 (20.7) | 67.2 (20.5) | ↑ 10 points | 0.07 | 0.48 |

| - SEAR-Self-Esteem (Range = 0–100) | 75.1 (24.1) | 66.4 (22.4) | ↑ 8.7 points | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| - SEAR-Relationship (Range = 0–100) | 65.6 (29.8) | 51.9 (22.8) | ↑ 13.7 points | 0.10 | 0.53 |

| -SEAR-Overall Relationship (Range = 0– 100) | 81.3 (25.8) | 69.8 (28.8) | ↑ 11.5 points | 0.17 | 0.42 |

| Sexual Bother (Range = 0–15) | 3.5 (2.2) | 4.5 (2.3) | ↓ 1.0 point | 0.17 | 0.43 |

| Prostate Cancer Treatment Regret (Range = 0–25) | 5.2 (2.4) | 7.7(3.7) | ↓ 2.5 points | 0.02 | 0.74 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Revised (Range = 0–60) | 25.6 (11.8) | 26.2 (6.6) | ↓ 0.6 points | 0.73 | 0.06 |

Note: ACT, n = 21; EM, n = 23; Cohen’s guide for interpreting effect sizes: small effect, d=0.2; medium effect, d=0.5; and large effect, d=0.8

Table 6:

Secondary Outcomes Eight Month Assessment

| Variable | ACT-ED Mean (SD) |

EM Mean (SD) |

Intervention Compared to Control |

p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED Treatment Satisfaction (Range = 0–44) | 32.0 (9.9) | 32.2 (7.0) | ↑ .2 points | 0.95 | 0.02 |

| Sexual Self-Esteem and Relationship Total (SEAR; Range = 0–100) | 70.8 (22.4) | 61.7 (22.8) | ↑ 9.1 points | 0.19 | 0.40 |

| - SEAR-Confidence (Range = 0–100) | 77.2 (19.9) | 73.3 (21.7) | ↑ 3.9 points | 0.55 | 0.19 |

| - SEAR-Self-Esteem (Range = 0–100) | 75.9 (22.8) | 72.3 (23.1) | ↑ 3.6 points | 0.61 | 0.16 |

| - SEAR- Sexual Relationship (Range = 0–100) | 67.1 (29.1) | 52.3 (28.0) | ↑ 14.8 points | 0.10 | 0.52 |

| - SEAR-Overall Relationship (Range = 0–100) | 79.8 (23.8) | 75.4 (26.4) | ↑ 4.4 points | 0.58 | 0.18 |

| Sexual Bother (Range = 0–15) | 7.4 (2.5) | 7.2 (2.4) | ↓ 0.2 points | 0.81 | 0.08 |

| Prostate Cancer Treatment Regret (Range = 0–25) | 7.4 (2.5) | 8.8 (3.3) | ↓ 1.4 points | 0.16 | 0.47 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Revised (Range = 0–60) | 24.9 (15.3) | 26.3 (5.3) | ↓ 1.4 points | 0.32 | 0.13 |

Note: ACT, n = 16; EM, n = 21; Cohen’s guide for interpreting effect sizes: small effect, d=0.2; medium effect, d=0.5; and large effect, d=0.8

Discussion

This intervention aimed to utilize Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) principles to increase compliance with use of penile injections. The ACT-ED intervention encouraged men to focus on the long-term goals of rehabilitation, accept the frustration and distress related to ED, utilize the concept of willingness, identify and overcome barriers, and commit to utilizing injections. The current pilot RCT results indicated that the ACT-ED intervention was feasibly delivered within the existing framework of a penile rehabilitation program and suggests that augmenting existing clinical care with theoretical elements of ACT can enhance men’s adherence to penile injections. Moreover, ACT-ED demonstrated initial efficacy to increase satisfaction with injections, sexual self-esteem and confidence, while reducing sexual bother and prostate cancer treatment regret relative to the control group.

Achieving one of the study’s primary aims, the intervention proved feasible within existing clinical practice. The effective acceptance rate was 61% which surpassed our a priori goal of 40% seen in other sexual focused interventions in men with prostate cancer. Additionally, the high ACT-ED intervention completion rate (85%) and equal levels of completion of study assessments for both arms are further indicators that participants found this intervention to be tolerable and acceptable. Feasibility was an important concern when developing the ACT-ED intervention and the study recruitment strategies. Based on our past qualitative work (14), we took care to use an approach and language that would resonate with men. Language was modified and focused on masculine concepts of goals, priorities, and action. In fact, our focus groups suggested we frame the intervention as “coaching” instead of “therapy.” As a result, the ACT-ED intervention was developed to use themes and techniques more in line with a “coaching” intervention as opposed to an intense “therapy” intervention. The feasibility results also likely reflect the specific focus and aim to integrate the intervention with existing care.

Adherence to penile injections was also a primary outcome and injection use and adherence were greater in the ACT-ED arm as compared to the EM group. The mean weekly injection use of 1.7 observed in the ACT-ED treatment arm was close to the 1.9 mean injection use reported by Mulhall (7), which demonstrated efficacy with penile rehabilitation. In addition, the 44% adherence rate demonstrated in the ACT-ED group is comparable to adherence rates for interventions with other cumbersome medical treatments such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for sleep apnea (45% compliance after intervention) (36). Additionally, the increase in compliance in the ACT-ED arm over the EM arm (44% vs. 10%) would rank among the top percentage increase compared to adherence interventions for other medications (37). The ACT intervention also seemed to have a lasting impact on injection use as greater adherence was maintained at the eight-month assessment (four months without the intervention) for the ACT-ED group compared to the EM group.

When considering these results, it is also important to consider the enhanced monitoring (EM) control intervention. The EM intervention was delivered by a NP with expertise in sexual medicine who reached out by phone to the control participants for the same number of sessions as the ACT-ED group. This provided control subjects encouragement to continue to use penile injections and a caring professional to troubleshoot problems and answer any questions. This is more support than is generally provided by sexual medicine programs. This indicates that encouragement and education alone have a ceiling effect on their effectiveness in helping men use injections. In this enhanced monitoring group, only 10% were injecting at a rate compliant with rehabilitation at four-months and 0% were compliant at eight-months. This is an indication that care providers should change the structure of the conversation, in addition to providing encouragement and education, to help men utilize ED treatments.

The ACT-ED intervention was developed from ACT concepts (16, 17) and input from focus groups (14). The intervention acknowledges that men experience significant distress when thinking about using ED treatment or entering sexual situations, and as result, can easily enter a “Cycle of Avoidance” when considering engaging in these types of activities. The ACT-ED intervention changes the structure of the discussion as compared to general encouraging and education. ACT-ED highlights a “Cycle of Acceptance and Commitment,” by focusing on the importance of the activity for the patient, the need to accept distress as part of the process, and the willingness to act even when experiencing anxiety. We believe that decreasing avoidance through principles of ACT facilitated men’s adherence to injections, allowing them to take a different psychological perspective towards using injections and pushing through discomfort to achieve value-concordant goals.

Importantly, the results indicate that ACT-ED had a positive effect on psychosocial variables including ED treatment satisfaction, sexual self-esteem, sexual bother, and prostate cancer treatment regret immediately following the study intervention. While this pilot study was not powered to achieve statistical significance, the effect size for all of these secondary outcomes was above d = 0.4, suggesting a moderate effect of these variables. Four months after treatment ended (i.e., the eight-month assessment), these effects were maintained for sexual self-esteem, sexual relationship, and prostate cancer treatment regret as both maintained moderate effect sizes (d > 0.4). We believe that these novel findings are due to the fact that the ACT-ED intervention builds on the previous work of psycho-sexual educational interventions (24, 38) and allows patients to address the broader impact of injection therapy and ED on sexual functioning as a barrier to treatment compliance, adding the important conceptual framework of reducing avoidance of ED treatments. It is also worth noting that including partners in the treatment was initially considered, but ultimately it was decided that an individual-level intervention may be most appropriate clinically for penile injection adherence in this context. However, future versions of the intervention and feedback from participants may indicate that focusing on dyads and potentially including other sex therapy techniques may improve adherence and sexual satisfaction outcomes.

There were no differences in depressive symptoms at either outcome time point. While we did anticipate an impact, it is possible that symptoms of anxiety would have been a more appropriate psychosocial outcome to measure. Moreover, we did not require an elevated cut-off score on the CES-D as an inclusion criterion for the study and although the ACT-ED group used injections more frequently than the EM group, they were still coping with ED and recovery following surgery. Additionally, these results seem to suggest that measures which focus more specifically on distress related to sexual outcomes (e.g. sexual self-esteem, ED bother, ED treatment satisfaction) may be more sensitive to change in sexually focused interventions as opposed to general measures of depression and anxiety.

This is a uniquely “combined” approach focusing on sexual issues in men with prostate cancer, fully integrating the psychotherapeutic intervention into the best practices medical treatment for ED following radical prostatectomy. As stated above, ACT-ED was designed as “coaching” as opposed to an intense psychotherapeutic intervention and this potentially allows for ACT-ED techniques to be transferable to other professionals. In the case of a rehabilitation program, a brief set of techniques could be used by nurses who train the patients on injections and interact with them through phone calls and follow-up visits. This would take advantage of existing patient contact and would assist NPs in learning new ways to communicate with the patient to reduce avoidance. The ACT-ED techniques are also easily transferable to other medical treatments for ED (i.e., PDE5i, vacuum devices) to help men utilize these treatments and integrate them into sexual relations. Lastly, the intervention was designed to be fully integrated into a sexual medicine program and support a mental health professional to deliver this intervention. If conducted outside of a research protocol, the three in-person sessions were constructed to be billable patient contacts. This would allow for a billing stream to develop a viable practice for a mental health professional within a sexual medicine clinic.

This pilot RCT study has important strengths. The ACT-ED intervention was developed using ACT theoretical concepts and with the input of men who have used penile injections. This initial test of the ACT-ED intervention was done with a randomized study using an objective measure of frequency of penile injections and secondary outcomes which focus specifically on distress related to sexual dysfunction. Despite these strengths, this study does have limitations. First, the pilot nature of this study and small sample size do not provide the power to demonstrate statistical significance for many differences with moderate effects. This is unfortunately the nature of pilot studies, and the goal was to demonstrate feasibility and initial efficacy as opposed to statistical significance. For powering future studies, it will be important to anticipate attrition due to unavoidable, complex medical issues such as switching to PDE5i oral medication or cancer recurrence as it occurs in this population. Another weakness of the study is the relatively short follow-up period for men who are hopefully recovering erections after radical prostatectomy. Participants were only followed for eight months and many were less than a year post surgery. This did not allow us to assess erectile function as a viable option. We are currently conducting a larger study to address these two primary weaknesses which will be powered to test for significant differences, as well as follow patients for 24 months post-surgery, in order to determine if there are differences in erectile function outcomes between groups who demonstrate different rates of using penile injections.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R21 CA 149536; T32CA009461; P30CA008748]. The funding sources had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing or the report, or deciding to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgment of Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R21 CA 149536; T32CA009461; P30CA008748].

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: Dr. John P. Mulhall, co-author on this submission, serves as the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Sexual Medicine, is a member of the Board of Directors for the Sexual Medicine Society of North American, and is the Chair of the Medical Advisory Board Association of Peyronie’s Disease Advocates.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.ACS. Cancer Facts and Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson CJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Mulhall JP. Back to baseline: erectile function recovery after radical prostatectomy from the patients’ perspective. J Sex Med. 2013;10(6):1636–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Walsh E, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1425–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson CJ, Deveci S, Stasi J, Scardino PT, Mulhall JP. Sexual bother following radical prostatectomyjsm. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 1):129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Q, Zhang Y, Wang J, Li S, Cheng Y, Guo J, et al. Erectile Dysfunction and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med. 2018;15(8):1073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll JL, Bagley DH. Evaluation of sexual satisfaction in partners of men experiencing erectile failure. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1990;16(2):70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, Waters WB, Flanigan RC. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2005;2(4):532–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulhall JP, Bella AJ, Briganti A, McCullough A, Brock G. Erectile function rehabilitation in the radical prostatectomy patient. J Sex Med. 2010;7(4 Pt 2):1687–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(8):1773–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salonia A, Abdollah F, Gallina A, Pellucchi F, Castillejos Molina RA, Maccagnano C, et al. Does educational status affect a patient’s behavior toward erectile dysfunction? The journal of sexual medicine. 2008;5(8):1941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Althof SE, Turner LA, Levine SB, Risen C, Kursh E, Bodner D, et al. Why do so many people drop out from auto-injection therapy for impotence? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1989;15(2):121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss JN, Badlani GH, Ravalli R, Brettschneider N. Reasons for high drop-out rate with self-injection therapy for impotence. International Journal of Impotence Research. 1994;6(3):171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson CJ, Hsiao W, Balk E, Narus J, Tal R, Bennett NE, et al. Injection anxiety and pain in men using intracavernosal injection therapy after radical pelvic surgery. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(10):2559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson CJ, Lacey S, Konowitz J, Pessin H, Shuk E, and Mulhall J. Men’s experience with penile rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy: A qualitative study with the goal of informing a therapeutic intervention . Psycho-Oncology. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, Neese L, Klein EA, Zippe C, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma.[see comment]. Cancer. 2002;95(8):1773–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes SC, Strosahl K, & Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavioral changes. New York: Guilford Press; . 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes SC. Get out of your mind and into your life...the new acceptance and commitment therapy: New Harbinger Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Molton I, Gonzalez JS, Kinsinger D, Roos BA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management improves stress-management skills and quality of life in men recovering from treatment of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(1):192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penedo FJ, Molton I, Dahn JR, Shen BJ, Kinsinger D, Traeger L, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(3):261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giesler RB GB, Given CW, Rawl S, Monahan P, Burns D, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma. A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nursedriven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104 752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lepore SJ HV, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishel MH BM, Germino BB, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Robertson C, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: Nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002. 94:1854–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Titta M, Tavolini IM, Moro FD, Cisternino A, Bassi P. Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy--results of a randomized prospective study. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological bulletin. 1992;112(1):155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8(4):1197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, Peterman AH, Schover LR. A 3-factor model for the FACIT-Sp. Psychooncology. 2008;17(9):908–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Althof SE, Corty EW, Levine SB, Levine F, Burnett AL, McVary K, et al. EDITS: development of questionnaires for evaluating satisfaction with treatments for erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1999;53(4):793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cappelleri JC, Althof SE, Siegel RL, Shpilsky A, Bell SS, Duttagupta S . Development and validation of the Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire in erectile dysfunction.[see comment]. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2004;16(1):30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Befort CA, Zelefsky MJ, Scardino PT, Borrayo E, Giesler RB, Kattan MW. A measure of health-related quality of life among patients with localized prostate cancer: results from ongoing scale development. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2005;4(2):100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroevers MJ, Sanderman R, van Sonderen E, Ranchor AV. The evaluation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale: Depressed and Positive Affect in cancer patients and healthy reference subjects. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9(9):1015–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sparrow D, Aloia M, Demolles DA, Gottlieb DJ. A telemedicine intervention to improve adherence to continuous positive airway pressure: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2010;65(12):1061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2008(2):CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers SK, Schover L, Halford K, Clutton S, Ferguson M, Gordon L, et al. ProsCan for Couples: randomised controlled trial of a couples-based sexuality intervention for men with localised prostate cancer who receive radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]