Abstract

Mitochondrial impairment is reported in HIV-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), as well as those naive to ART. Whether mitochondrial function recovers with early initiation of ART and sustained viral suppression on long-term ART is unclear. In this study, we evaluate mitochondrial markers in well-suppressed perinatally HIV-infected children initiated on ART early in life. We selected a cross-sectional sample of 120 HIV-infected children with viral load <400 copies/mL and 60 age-matched uninfected children (22 HIV-exposed uninfected) enrolled in a cohort study in Johannesburg, South Africa. Complex IV (CIV) and citrate synthase (CS) activity were measured by spectrophotometry. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content relative to nuclear DNA (nDNA) was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and expressed as copies/nDNA. Mitochondrial markers were impaired in HIV-infected children, including lower mean CIV activities [1.76 vs. 1.40 optical densities (OD)/min], higher risk of a CIV/CS ratio ≤0.22 (third quartile; odds ratio = 3.03, 95% confidence interval: 1.38–6.66), and lower mtDNA content. Children with shorter versus longer ART duration (<6.3 vs. ≥6.3 years) had lower means of CIV activity (1.22–1.58 OD/min) and mtDNA content (386–907 copies/nDNA). There were no differences in mitochondrial markers between children who started ART earlier (<6 months) or later (6–24 months). CIV activity was impaired in children with lower height-for-age Z-scores (HAZs). Despite early treatment and prolonged viral suppression, HIV-infected children had detectable mitochondrial impairment, particularly among those with stunted growth. Further study is required to determine if continued treatment will lead to full recovery of mitochondrial function in HIV-infected children.

Keywords: mitochondria, impairment, HIV, children, ART

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) in perinatally HIV-infected children is effective for improving immune function and extending survival. However, numerous immunologic and metabolic abnormalities, including mitochondrial dysfunction, are known to persist despite suppressive ART.1 Alterations of mitochondrial markers, often of uncertain etiology, are reported in HIV-infected children naive to ART,2 as well as those on treatment.3–6

Many studies suggest a joint adverse effect of HIV infection and ART, especially the use of older nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), such as stavudine (d4T) and lamivudine (3TC), on mitochondrial function.3–6 Use of d4T and 3TC was reported to significantly increase the risk of mitochondrial dysfunction in perinatally HIV-infected children.3 Mitochondrial markers, including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content, complex I, complex III, and complex IV (CIV) enzymatic activities, have been reported to be different between treated HIV-infected and uninfected children in some4–6 but not all studies.7–9

Associations between mitochondrial markers and viral load (VL) and CD4 counts/percentages in HIV-infected children are less well studied, and prior reports are limited by small sample sizes.6,10 Only a single study conducted in adults found that mtDNA levels were associated with CD4 counts but inversely associated with VL.11 To our knowledge, no study has investigated the relationships between mitochondrial markers, age at ART initiation or duration on ART in HIV-infected children initiating treatment early in life, and whether mitochondrial markers recover with sustained viral suppression and long-term ART. Although prior studies indicate that suboptimal growth commonly occurs in HIV-infected children on long-term treatment,12–14 none have investigated the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-associated growth impairment.

The aim of this study was to evaluate mitochondrial markers in perinatally HIV-infected children who initiated ART early in life and achieved sustained long-term viral suppression. These markers were compared with age-matched uninfected children enrolled in a cohort study in Johannesburg, South Africa. We also investigated whether anthropometric characteristics and HIV-related clinical, immunologic, and virologic characteristics were associated with alterations in mitochondrial markers.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

The Childhood HAART Alterations in Normal Growth, Genes, and aGing Evaluation Study (CHANGES) is a longitudinal cohort study of 553 perinatally HIV-infected, ART-treated children and 300 HIV-uninfected children ages 4–9 years at enrollment. Participants were recruited from the Empilweni Service and Research Unit (ESRU) at Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital and the Perinatal HIV Research Unit (PHRU) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. HIV-uninfected children were selected from siblings, household members, and other contacts of HIV-infected participants and were excluded from enrollment if they had known chronic medical conditions (pneumonia, asthma, seizures, and developmental or neurological problems) or did not have a confirmed negative HIV test. Mitochondrial diseases were not specifically screened for in this cohort.

From the CHANGES study, 120 HIV-infected children were randomly selected from those who initiated a ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (LPV/r) regimen, had never interrupted therapy, and had a plasma VL < 400 copies/mL at the time of enrollment into the cohort study. All children had sustained viral suppression for a median of 2.4 years (range 0.6–7.2 years) by the time of study. Half of the children had initiated ART < 6 months of age and half 6–24 months of age. A random sample of 60 HIV-uninfected children was selected from the cohort of controls age matched to the selected HIV-infected children. The uninfected group included 22 (36.7%) HIV exposed uninfected children, 37 (61.7%) HIV unexposed uninfected children, and 1 child (1.6%) in which the maternal HIV status was unknown.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa). Written informed consent was obtained from all children's parent or guardian. Written assent was obtained from children ≥7 years of age who were assessed as having sufficient mental capacity to provide informed assent.

Measurements

Demographics and clinical characteristics were obtained from questionnaires, medical record review, and clinical examination. A digital scale and a wall-mounted stadiometer, respectively, measured weight to the nearest 0.1 kg and height to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ), height-for-age Z-score (HAZ), and body mass index (BMI)-for-age Z-score (BAZ) were determined using the WHO Child Growth Standards (www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en). BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Underweight, stunting, and overweight were, respectively, defined as WAZ < −2, HAZ < −2, and BAZ > 1.

Plasma VL was measured by the Abbott RealTime HIV-1 Assay (Abbott Park, IL), and CD4+ T cell counts/percentages were measured by the TruCount Method (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) at enrollment and at every subsequent 6-month visit.

Whole blood was collected and processed within 6 h to prepare buffy coat, which was stored at −80°C in South Africa before being shipped frozen to the United States. Three mitochondrial markers, CIV, citrate synthase (CS), and mtDNA content, were measured at the first 6-month follow-up visit for HIV-infected children and the initial baseline visit for uninfected children. This time-point discrepancy was necessary because the baseline samples of HIV-infected children were used for another study.

CIV and CS activity were obtained by spectrophotometry using the Abcam® Complex IV Human Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit and the Abcam Human Citrate Synthase Activity Assay Kit, respectively.15–17 Briefly, 10 and 120 μg of total buffy coat protein were added to each well of both assays, respectively. Microtiter plates were coated with enzyme-specific antibodies that captured only native protein. Activity of CIV was determined by the rate of change in oxidation of reduced cytochrome c and read as change in optical densities per minute (OD/min) measured at 550 nm. Activity of CS was determined by the rate of change in product (TNB) resulting from adding substrate (DTNB) and read as change in OD/min measured at 412 nm. Isolation of mitochondria was not required for these assays as the monoclonal antibodies capture intact enzyme after protein solubilization. Samples were run in triplicate, and an investigator positive control sample was prepared in the same manner as patient samples and used in all assays as a measure of intra-assay variability.

Genomic DNA was isolated from buffy coat sample by QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instruction. The extracted DNA was quantified by PicoGreen spectrophotometry and frozen at −80°C until used for mtDNA quantification. mtDNA content relative to nuclear DNA (nDNA) was determined using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by separately amplifying highly-conserved mitochondrial 12S RNA and nuclear housekeeping gene (RNase P).18 The PCR mix included 100 ng genomic DNA, mtDNA forward primer (5′-CCA CGG GAA ACA GCA GTG ATT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-CTA TTG ACT TGG GTT AAT CGT GTG A-3′), mtDNA TaqMan probe (FAM-TGC CAG CCA CCG CG-MGB), TaqMan RNase P Control (VIC dye), and Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Samples were run in triplicate on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System under the conditions of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min. mtDNA content was calculated by delta cycle threshold (Ct) approach as 2−(Ct of mtDNA − Ct of nDNA), that is, 2−ΔCt and expressed as copies/nDNA.19 The assays were optimized over multiple positive control sample runs from unrelated stored samples frozen up to 10 years at −80°C and fresh investigator samples before the use of patient buffy coat protein or DNA. All assays were run in the laboratory of Dr. Philip LaRussa, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Columbia University Medical Center under the direction of Dr. Marc Foca. Laboratory technicians were blinded to HIV status and other clinical characteristics.

Statistical analyses

The distributions of mitochondrial markers were described by HIV status using Univariate Analysis of Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. We compared the means or medians of continuous variables using a two-sample t-test, one-way analysis of variance, or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum (Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis) test, as appropriate, followed by a post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test. The generalized linear model (GLM) or quantile regression was used to estimate the difference (β) and p-value, adjusted for potential confounders. As the ratio of CIV/CS was highly skewed from a normal distribution even after log transformation, the third quartile was used to categorize CIV/CS as normal (>0.22) or impaired (≤0.22). Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test if cell counts <5. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of categorical variables, as well as OR adjusted for potential confounders. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to examine the correlations between mitochondrial markers and clinical characteristics.

Mitochondrial markers were compared in HIV-infected children by categorical anthropometric characteristics (WAZ, HAZ, and BAZ), age at ART initiation, and duration on ART. Associations between VL and CD4 counts/percentages ascertained before ART initiation and mitochondrial markers were also examined. If VL (n = 8) and/or CD4 (n = 10) were missing at the exact time of marker measurement, data were imputed from the enrollment visit 6 months earlier.

All statistical analyses were performed by SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and two-sided p-value <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study sample characteristics

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics at the time of mitochondrial marker measurement are shown in Table 1. Mean age of HIV-infected children was just over 6 months older than uninfected children (7.0 vs. 6.4 years, p = .022), and age- and sex-adjusted anthropometric Z-scores were significantly lower in HIV-infected compared to uninfected children. Earlier treated children who started ART under 6 months of age were younger at time of mitochondria measurement than children who started ART later (6–12 months) (Table 1. p = −.001). All 120 HIV-infected children were suppressed (VL < 400 copies/mL) at the time of enrollment, and 109 remained suppressed at the time of marker measurement. Pre-ART CD4 counts and percentages were significantly higher in earlier treated children (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of 60 HIV-Uninfected and 120 HIV-Infected Children by Age at Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation, Johannesburg, South Africa

| Demographic and anthropometric characteristics | Uninfected children | HIV-infected children | p | Age at ART initiation |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 Months | 6–12 Months | |||||

| No. of subjects (N) | 60 | 120 | 60 | 60 | ||

| Male, N (%) | 34 (56.7) | 56 (46.7) | .207 | 29 (48.3) | 27 (45.0) | .715 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.4) | .022 | 6.6 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.5) | .001 |

| WAZ, mean (SD) | −0.2 (0.9) | −0.7 (0.9) | .0003 | −0.8 (0.8) | −0.6 (1.1) | .171 |

| Underweight (WAZ < −2), N (%) | 0 (0) | 11 (9.2) | .010a | 6 (10.0) | 5 (8.3) | .753 |

| HAZ, mean (SD) | −0.7 (1.0) | −1.0 (0.9) | .018 | −1.1 (1.0) | −0.9 (0.9) | .423 |

| Stunting (HAZ < −2), N (%) | 5 (8.3) | 18 (15.0) | .213 | 10 (16.7) | 8 (13.3) | .610 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 16.2 (1.9) | 15.4 (1.7) | .009 | 15.1 (1.3) | 15.7 (2.0) | .073 |

| BAZ, mean (SD) | 0.3 (1.0) | −0.1 (1.0) | .005 | −0.2 (0.9) | −0.02 (1.1) | .278 |

| Overweight (BAZ > 1), N (%) | 12 (20.0) | 19 (15.8) | .486 | 8 (13.3) | 11 (18.3) | .455 |

Fisher's exact test due to small cell counts.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; BAZ, BMI-for-age Z-score; BMI, body mass index; HAZ, height-for-age Z-score; WAZ, weight-for-age Z-score; SD, standard deviation.

Significant p-values are noted in bold.

Table 2.

Preantiretroviral Therapy and Current Clinical Characteristics of 120 HIV-Infected Children by Age at Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation, Johannesburg, South Africa

| Clinical characteristics | HIV-infected children | Age at ART initiation |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 Months | 6–12 Months | |||

| No. of subjects (N) | 120 | 60 | 60 | |

| Initial ART regimen, N (%) | ||||

| LPV/r plus 3TC plus ABC or AZT or d4Ta | 110 (91.7) | 56 (93.3) | 54 (90.0) | |

| RTV plus 3TC plus AZT or d4Ta | 10 (8.3) | 4 (6.7) | 6 (10.0) | .743b |

| Age at ART initiation (months), mean (SD) | 7.8 (6.1) | 3.2 (1.3) | 12.3 (5.5) | |

| Pre-ART VL (copies/mL), N (%) | ||||

| <750,000 | 41 (41.8) | 20 (38.5) | 21 (45.7) | |

| ≥750,000 | 57 (58.2) | 32 (61.5) | 25 (54.3) | .472 |

| Pre-ART CD4 counts (cells/mL), mean (SD) | 1,400 (922.9) | 1,660.7 (936.4) | 1,115.6 (825.9) | .002 |

| Pre-ART CD4 counts (cells/mL), N (%) | ||||

| <1,000 | 44 (39.6) | 15 (25.9) | 29 (54.7) | |

| ≥1,000 | 67 (60.4) | 43 (74.1) | 24 (45.3) | .002 |

| Pre-ART CD4 percentage, mean (SD) | 20.1 (11.1) | 27.3 (10.6) | 22.7 (11.3) | .026 |

| Pre-ART CD4 percentage, N (%) | ||||

| <25% | 58 (51.3) | 25 (42.4) | 33 (61.1) | |

| ≥25% | 55 (48.7) | 34 (57.6) | 21 (38.9) | .048 |

| Current ART regimen, N (%) | ||||

| LPV/r plus 3TC plus ABC or AZT or d4Ta | 118 (98.4) | 59 (98.3) | 59 (98.3) | |

| EFV plus 3TC plus ABC | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1.000b |

| Duration of ART (years), mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.4) | 6.2 (1.2) | 6.3 (1.6) | .835 |

| Current VL (copies/mL), N (%) | ||||

| <400 | 109 (90.8) | 57 (95.0) | 52 (86.7) | |

| ≥400 | 11 (9.2) | 3 (5.0) | 8 (13.3) | .127 |

| Current CD4 counts (cells/mL), mean (SD) | 1,084 (399.8) | 1,049 (430.6) | 1,120 (366.6) | .332 |

| Current CD4 counts (cells/mL), N (%) | ||||

| <1,000 | 60 (50.0) | 34 (56.7) | 26 (43.3) | |

| ≥1,000 | 60 (50.0) | 26 (43.3) | 34 (56.7) | .145 |

| Current CD4 percentage, mean (SD) | 33.8 (7.1) | 32.9 (7.5) | 34.8 (6.5) | .139 |

| Current CD4 percentage, N (%) | ||||

| <25% | 11 (9.2) | 7 (11.7) | 4 (6.7) | |

| ≥25% | 109 (90.8) | 53 (88.3) | 56 (93.3) | .348 |

At the time of mitochondrial marker measurement.

Initial regimen of LPV/r plus 3TC plus ABC (N = 5) or AZT (N = 21) or d4T (N = 84); initial regimen of RTV plus 3TC plus AZT (N = 1) or d4T (N = 9); current regimen of LPV/r plus 3TC plus ABC (N = 72) or AZT (20) or d4T (N = 26).

Fisher's exact test due to small cell counts.

3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; EFV, efavirenz; LPV/r, ritonavir-boosted lopinavir; VL, viral load.

Significant p-values are noted in bold.

Mitochondrial markers by HIV status

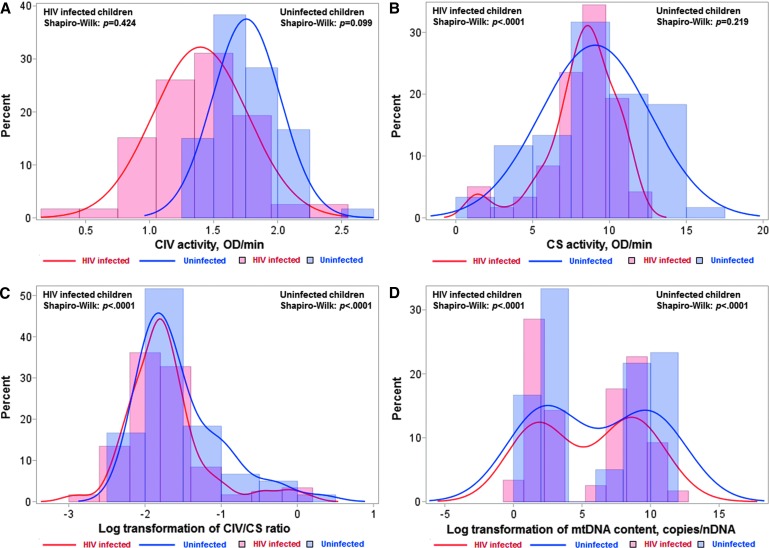

CIV activity was normally distributed in both HIV-infected and uninfected children, but was shifted to lower CIV values in HIV-infected children (Fig. 1A). The mean CIV activity was lower in HIV-infected compared with uninfected children (1.40 vs. 1.76 OD/min, p < .0001), a difference that remained significant after adjusting for age (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Histograms and normality tests for distribution of mitochondrial markers by HIV status. Distribution of CIV activity (A), CS activity (B), CIV/CS ratio (C), and mtDNA content (D) is shown in HIV-infected (red line and histogram) and uninfected children (blue line and histogram). Shapiro–Wilk normality test p-value of > .05 indicates a normal distribution. CIV, complex IV; CS, citrate synthase; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Table 3.

Comparisons of Complex IV, Citrate Synthase, Complex IV/Citrate Synthase Ratio, and Mitochondrial DNA Content in 120 HIV-Infected and 60 Uninfected Children in Johannesburg, South Africa

| Mitochondrial markers | HIV uninfected |

HIV infected |

p | Age at ART initiation |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Children | 6–12 Months | <6 Months | |||

| No. of subjects (N) | 60 | 120 | 60 | 60 | ||

| CIV activity, OD/min | ||||||

| Median | 1.74 | 1.38 | <.0001 | 1.41 | 1.37 | .909 |

| IQR | 1.64–1.93 | 1.16–1.63 | 1.21–1.68 | 1.08–1.61 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.76 (0.27) | 1.40 (0.37) | 1.43 (0.36) | 1.36 (0.39) | ||

| Unadjusted β | −0.36 | <.0001 | −0.08 | .254 | ||

| Age adjusted βa | −0.40 | <.0001 | 0.03 | .654 | ||

| CS activity, OD/min | ||||||

| Median | 9.29 | 8.45 | .048 | 8.42 | 8.69 | .578 |

| IQR | 5.98–11.99 | 7.22–9.67 | 7.54–9.60 | 6.95–9.67 | ||

| Unadjusted β | −0.84 | .135 | 0.11 | .809 | ||

| Age adjusted βa | −0.81 | .153 | 0.29 | .524 | ||

| CIV/CS ratio, third quartile, N (%) | ||||||

| >0.22 | 19 (31.7) | 21 (17.7) | 12 (20.0) | 9 (15.2) | ||

| ≤0.22 | 41 (68.3) | 98 (82.3) | 48 (80.0) | 50 (84.8) | ||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 2.16 (1.05–4.44) | .036 | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.39 (0.54–3.59) | .498 |

| Age adjusted OR (95% CI)a | 1.00 (Ref.) | 3.03 (1.38–6.66) | .006 | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.82 (0.29–2.33) | .707 |

| Low mtDNA content, <12 copies/nDNA | N = 30 | N = 56 | N = 28 | N = 28 | ||

| Median | 5.24 | 3.25 | .119 | 2.67 | 3.59 | .195 |

| IQR | 2.69–8.31 | 2.33–5.12 | 2.30–4.90 | 2.89–5.12 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.44 (2.76) | 3.88 (2.11) | 3.58 (2.03) | 4.20 (2.18) | ||

| Unadjusted β | −1.55 | .005 | 0.63 | .274 | ||

| Age adjusted βa | −1.43 | .014 | 0.57 | .383 | ||

| High mtDNA content, >50 copies/nDNA | N = 30 | N = 64 | N = 32 | N = 32 | ||

| Median | 961 | 424 | .012 | 389 | 474 | .714 |

| IQR | 555–1,484 | 220–670 | 196–667 | 269–695 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1,116 (754) | 639 (800) | 633 (971) | 644 (599) | ||

| Unadjusted β | −477 | .007 | 11 | .958 | ||

| Age adjusted βa | −484 | .005 | 101 | .586 | ||

Adjusted for age at mitochondrial marker measurement.

CI, confidence interval; CIV, complex IV; CS, citrate synthase; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; nDNA, nuclear DNA; OD, optical densities; OR, odds ratio.

CS activity was skewed away from normality in HIV-infected children (W statistic = 0.910, p < .0001) (Fig. 1B). The median CS activity was slightly lower in HIV-infected children compared to uninfected children (8.45 vs. 9.29 OD/min), but this difference was not significant (Table 3).

After log transformation, the CIV/CS ratio was still highly skewed from normality in both groups (Fig. 1C); therefore, we categorized CIV/CS ratio by the third quartile as normal (>0.22) versus impaired (≤0.22) throughout the analysis. HIV-infected children had an increased risk of impaired CIV/CS ratio (unadjusted OR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.05–4.44) compared to uninfected children. This difference was accentuated after adjusting for age (adjusted OR = 3.03, 95% CI: 1.38–6.66, Table 3).

After log transformation, mtDNA content was bimodally distributed in both HIV-infected and uninfected children (Fig. 1D). Therefore, we stratified the children as follows: those with low mtDNA content (<12 copies/nDNA) and high mtDNA content (>50 copies/nDNA). The distribution of mtDNA content was approximately normal when separated into these two strata (Supplementary Fig. S1). Within each stratum, mtDNA content was lower in HIV-infected compared with uninfected children. Mean mtDNA contents were 3.88 and 5.44 copies/nDNA (β = −1.55, p = .005) in HIV-infected and uninfected children, respectively, in the stratum with low levels. Means of mtDNA were 639 and 1,116 copies/nDNA (β = −477, p = .007), respectively, in the stratum with high levels (Table 3). Differences between HIV-infected and uninfected children remained significant within both the low (p = .014) and the high (p = .005) mtDNA content strata after adjustment for age (Table 3).

Mitochondrial markers by age at ART initiation

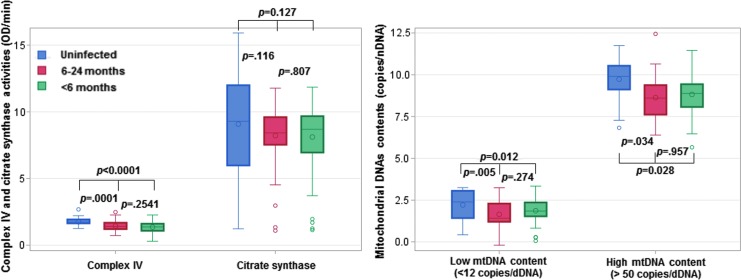

There were no significant differences in any of the mitochondrial markers between children who started ART earlier and later (Table 3) and this did not change after adjustment for age. Compared to uninfected children, infected children had lower levels of CIV activity regardless of age at ART initiation. In CS and both low and high mtDNA strata, there was a suggestion of a gradient favoring earlier ART initiation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Box and whisker plots to compare mitochondrial markers in uninfected and infected children by age at ART initiation (<6 vs. 6–24 months). One-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between three groups followed by a post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test to calculate p-values. Red, blue, and green colors, respectively, represent uninfected children, infected children with age at ART initiation at 6–24, and infected children with age at ART initiation <6 months. Box and whisker plot shows the mean, median, the third quartile (Q3), and first quartile (Q1) range of CIV, CS, low mtDNA (<12 copies/nDNA) content, high mtDNA (>50 copies/nDNA) content, as well as the outlier data outside the 9–91 percentile range. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ART, antiretroviral therapy; nDNA, nuclear DNA.

Mitochondrial markers by duration on ART

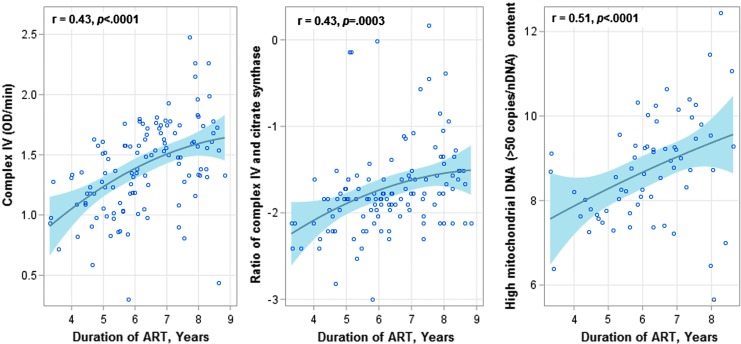

Duration on ART was significantly associated with increasing CIV activity (r = 0.51, p < .0001), CIV/CS ratio (r = 0.43, p < .0001), and mtDNA content in the high stratum (r = 0.43, p = .0003) (Fig. 3), but not correlated with CS activity and mtDNA content in the low stratum.

FIG. 3.

Scatter plots for the associations between years of ART (x-axis) and CIV activity, log(CIV/CS) ratio, and high mtDNA (>50 copies/nDNA) contents (y-axis) in HIV-infected children. The solid lines and shadings, respectively, indicate the linear fit of each marker with duration of ART and 95% confidence limits. p-Value of <.05 indicates a significant linear correlation.

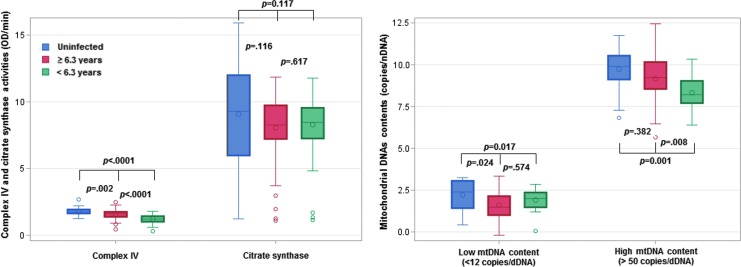

Comparing HIV-infected children who had been on ART for <6.3 years (median duration on ART in the group), CIV activity was higher in children who had been on ART for ≥6.3 years (1.58 vs. 1.22 OD/min, Table 4). However, even in the HIV-infected children who had been on ART longer, CIV activity was lower than that in uninfected children (1.58 vs. 1.76 OD/min) even after adjusting for age (Fig. 4). No significant differences in CS activity were observed between HIV-infected children on ART for ≥6.3 and <6.3 years (Fig. 4). An impaired CIV/CS ratio was less likely to be observed in HIV-infected children who had longer duration on ART (OR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06–0.56, Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparisons of Complex IV, Complex IV/Citrate Synthase Ratio, and Mitochondrial DNA Content in 120 HIV-Infected Children by Preantiretroviral Therapy Viral Load, Duration on Antiretroviral Therapy, and Height-for-Age Z-Scores in Johannesburg, South Africa

| Characteristics | CIV activity, OD/min |

CIV/CS ratioa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | >0.22 | ≤0.22 | OR (95% CI) | |

| Duration of ART, years | |||||

| <6.3 | 1.22 | 4 (6.7) | 56 (93.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) | |

| ≥6.3 | 1.58 | 17 (28.8) | 42 (71.2) | ||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) | 0.36 (0.24 to 0.48) | <.0001 | 0.18 (0.06 to 0.56) | ||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI) | 0.20 (−0.02 to 0.41) | .079 | 0.36 (0.04 to 2.95) | ||

| Pre-ART VL (copies/mL) | |||||

| <750,000 | 1.32 | 6 (14.6) | 35 (85.4) | 1.00 (Ref.) | |

| ≥750,000 | 1.49 | 11 (19.6) | 45 (80.4) | ||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) | 0.16 (0.02 to 0.31) | .027 | 0.70 (0.24 to 2.08) | ||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI) | 0.15 (0.02 to 0.27) | .024 | 0.74 (0.24 to 2.37) | ||

| Duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) | 0.13 (0.00 to 0.26) | .050 | 0.83 (0.26 to 2.61) | ||

| Age/duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) | 0.14 (0.01 to 0.27) | .030 | 0.75 (0.23 to 2.42) | ||

| HAZ at marker measurement | |||||

| Greater than −1 | 1.53 | 15 (25.9) | 43 (74.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | |

| −1 to −2 | 1.30 | 5 (11.6) | 38 (88.4) | ||

| Less than −2 (stunting) | 1.20 | 1 (5.6) | 17 (94.4) | ||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI), −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.23 (−0.37 to −0.10) | .001 | 2.65 (0.88 to 7.98) | ||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.33 (−0.53 to −0.13) | .002 | 5.93 (0.73 to 48.46) | ||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI), −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | .162 | 1.32 (0.38 to 4.58) | ||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.16 (−0.38 to 0.06) | .161 | 1.14 (0.11 to 12.47) | ||

| Duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) | −0.10 (−0.24 to 0.04) | .156 | 1.41 (0.42 to 4.77) | ||

| −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 | |||||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.18 (−0.41 to 0.04) | .107 | 1.68 (0.17 to 16.73) | ||

| Age/duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) | −0.09 (−0.24 to 0.05) | .185 | 1.32 (0.38 to 4.55) | ||

| −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 | |||||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.16 (−0.39 to 0.06) | .157 | 1.16 (0.11 to 12.66) | ||

| Characteristics | Low mtDNA content (<12 copies/nDNA) |

High mtDNA content (>50 copies/nDNA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | p | N | Mean | p | |||

| Duration of ART, years |

||||||||

| <6.3 |

27 |

4.05 |

|

33 |

386 |

|

||

| ≥6.3 |

29 |

3.72 |

|

31 |

907 |

|

||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) |

|

−0.32 (−1.47 to 0.82) |

.574 |

|

521 (140 to 902) |

.008 |

||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI) |

|

0.11 (−2.39 to 2.60) |

.932 |

|

−111 (−726 to 504) |

.719 |

||

| Pre-ART VL (copies/mL) |

||||||||

| <750,000 |

15 |

3.93 |

|

26 |

553 |

|

||

| ≥750,000 |

31 |

4.04 |

|

26 |

669 |

|

||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI) |

|

0.10 (−1.34 to 1.54) |

.888 |

|

116 (−344 to 577) |

.614 |

||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI) |

|

0.09 (−1.36 to 1.54) |

.900 |

|

31 (−393 to 457) |

.880 |

||

| Duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) |

|

0.11 (−1.34 to 1.57) |

.878 |

|

34 (−404 to 473) |

.876 |

||

| Age/duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) |

|

0.07 (−1.46 to 1.59) |

.927 |

|

38 (−392 to 467) |

.861 |

||

| HAZ at marker measurement |

||||||||

| Greater than −1 |

28 |

4.21 |

|

31 |

787 |

|

||

| −1 to −2 |

22 |

3.45 |

|

21 |

554 |

|

||

| Less than −2 (stunting) |

6 |

3.99 |

|

12 |

404 |

|

||

| Unadjusted β (95% CI), −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−0.76 (−2.02 to 0.50) |

.232 |

|

−233 (−725 to 259) |

.347 |

||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−0.22 (−2.42 to 1.98) |

.842 |

|

−383 (−983 to 218) |

.205 |

||

| Age adjusted β (95% CI), −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−1.27 (−2.74 to 0.20) |

.089 |

|

82 (−405 to 570) |

.736 |

||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−0.65 (−3.55 to 2.25) |

.650 |

|

−103 (−729 to 524) |

.743 |

||

| Duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI) −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−1.10 (−2.51 to 0.31) |

.123 |

|

98 (−416 to 612) |

.703 |

||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−0.47 (−3.17 to 2.23) |

.726 |

|

−71 (−716 to 573) |

.824 |

||

| Age/duration on ART adjusted β (95% CI), −1 to −2 vs. greater than −1 |

|

−1.33 (−2.84 to 0.18) |

.083 |

|

80 (−428 to 588) |

.754 |

||

| Less than −2 vs. greater than −1 | −0.71 (−3.70 to 2.28) | .633 | −80 (−730 to 571) | .806 | ||||

Categorized by the third quartile.

FIG. 4.

Box and whisker plots to compare mitochondrial markers in uninfected and infected children by duration of ART (<6.3 vs. ≥6.3 years). One-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between three groups followed by a post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test to calculate p-values. Red, blue, and green colors, respectively, represent uninfected children, infected children with duration of ART <6.3, and infected children with duration of ART ≥6.3 years. Box and whisker plot shows the mean, median, the third quartile (Q3), and first quartile (Q1) range of CIV, CS, low and high mtDNA contents, as well as the outlier data outside the 9–91 percentile range.

In the low mtDNA content stratum, children who had longer duration on ART did not differ from those who had been on ART for less time (3.72 vs. 4.05 copies/nDNA, Table 4), but regardless of ART duration, HIV-infected children had lower mtDNA content than uninfected children (5.44 copies/nDNA) (Fig. 4). In the high mtDNA content stratum, children who had been on ART for a longer duration had higher mtDNA content than those who had been on ART for less time (907 vs. 386 copies/nDNA, p = .008, Table 4). MtDNA content in those on ART for a longer duration was similar to uninfected children (907 vs. 1,116 copies/nDNA, p = .382) (Fig. 4).

Mitochondrial markers by clinical, immunologic, and virologic characteristics

We found a higher pre-ART VL to be associated with higher CIV activity (β = 0.16, Table 4). The association persisted after adjustment for age (β = 0.15) or both age and duration on ART (β = 0.14). This association did not change even after adjusting for other pre-ART characteristics (β: 0.14–0.15, data not shown), although there were no associations between other pre-ART characteristics and mitochondrial markers.

At the time of the study, we observed an association between HAZ and CIV activity, but not other characteristics and mitochondrial markers (Table 4). CIV activity was lower (mean = 1.20 OD/min) in stunted children (HAZ < −2) and children with HAZ between −2 and −1 (mean = 1.30 OD/min) compared to those with HAZ > −1 (mean = 1.53 OD/min).

Discussion

In a well-characterized pediatric cohort, we found that multiple mitochondrial markers (CIV, CS, CIV/CS ratio, and mtDNA content) were impaired in HIV-infected children relative to uninfected children despite initiation of ART early in life and sustained viral suppression over many years. CIV and CS activities were 23% lower (1.76 vs. 1.40 OD/min) and 9% lower (9.29 vs. 8.45 OD/min) in HIV-infected versus uninfected children, respectively. HIV-infected children were more likely to have a low CIV/CS ratio than uninfected children. mtDNA content was 26% lower (3.88 vs. 5.44 copies/nDNA) and 43% lower (639 vs. 1,116 copies/nDNA) in HIV-infected versus uninfected children in low and high strata, respectively, using an analytic approach to account for the bimodal distribution of mtDNA. The impaired CIV, CIV/CS ratio, and mtDNA content in HIV-infected children remained significant after adjustment for age.

The mitochondrial markers we measured represent different aspects of mitochondrial function. CIV is a protein complex of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) involved in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. CS activity represents mitochondrial mass (MM), the CIV/CS ratio reflects the potential respiratory activity for a given MM, and mtDNA content represents replication efficiency.6 Two previous studies reported that mtDNA content diminished 17%–44% in HIV-infected children on ART compared to uninfected children.2,6 Three other studies also found mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-infected children on ART, but the degree of impairment was not reported.3–5 Our findings are in agreement with these studies and add to the literature by delineating mitochondrial impairment in a relatively homogenous group of HIV-infected children well suppressed on ART. In contrast, a few studies observed no difference in mitochondrial markers in HIV-infected children on ART and uninfected children.7–9

For HIV-infected children with longer duration on ART (≥6.3 years), CIV activity and high mtDNA content were increased 30% (from 1.22 to 1.58 OD/min) and 135% (from 386 to 907 copies), respectively, compared to shorter duration on ART. However, mitochondrial activity remained below that of uninfected children. Saitoh et al. found that mtDNA content was low (137 copies/cell) at baseline, but increased to 179 and 198 copies/cell, respectively, after 48 and 104 weeks on ART in HIV-infected children.10 Studies in adults also confirmed the finding of increased mtDNA content in HIV-infected patients receiving ART with viral suppression.11,20 However, other studies found greater loss of mtDNA content over time with long-term treatment in HIV-infected children4 and adults.21,22

There are a number of possible explanations for mitochondrial impairment in our study sample of HIV-infected children with prolonged viral control who were initiated on ART early in life. Despite suppression of plasma VL to low concentrations, viral reservoirs23 and viral associated proteins may persist,24,25 thereby impairing mitochondrial function. Previous studies indicated that at least three HIV-related proteins—viral protein R (Vpr),26,27 trans-activator of transcription (Tat),28 and glycoprotein 120 (gp120)29—have been associated with mitochondrial impairment. In viral reservoirs, a small subset of infected cells still express viral messenger RNA (mRNA) and proteins,30 while reactivation of latent HIV downregulated 26 proteins that participated in mitochondrial protein synthesis31 and attributed to mitochondrial impairment. In addition, in vitro studies have found that NRTIs, including d4T, zidovudine (AZT), 3TC, and abacavir (ABC), have an inhibitory effect on DNA polymerase-γ (Pol-γ),32 which is responsible for mtDNA synthesis. However, we found that mitochondrial markers improved with longer duration of therapy suggesting that ART may benefit mitochondrial recovery in the short term, despite some role in residual mitochondrial dysfunction. Understanding the relative contributions of long-term ART, viral proteins, and other factors on mitochondrial impairment requires further investigation.

We observed significantly decreased CIV activity in HIV-infected children with lower HAZ compared to those with normal HAZ. CIV activity was reduced 15% (from 1.53 to 1.30 OD/min) for children with lower HAZ (between −2 and −1) and 22% (from 1.53 to 1.20 OD/min) for stunted children (HAZ ≤ −2). Although prior studies indicated improved linear growth with ART,13,33,34 low HAZ and chronic stunting remain common among HIV-infected children despite ART,12–14 and the etiology for reduced statural growth is not well established.

Prior studies of growth attenuation among HIV-infected children have suggested a number of factors, including poor nutrient intake and malabsorption, elevated energy expenditures, and neuroendocrine dysfunction.35–41 Our results suggest that impaired energy utilization related to altered mitochondrial function may also play a role in persistent stunting of HIV-infected children. Short stature is a common characteristic in children with inherited mitochondrial diseases, such as mitochondrial myopathy, MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes), MERRF (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers), NARP (neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa), and LHON (Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy).42–44 Defective oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondrial disease results in reduced intracellular synthesis and secretion of hormones,45,46 leading to insufficiency of a number of growth regulatory hormones,47 and contributes to suboptimal linear growth. Although no single abnormality has consistently been identified as associated with reduced statural growth in children with HIV, studies conducted before availability of potent ART identified a number of endocrinologic disturbances, including hypothyroidism, alterations in hypothalamic pituitary axis, growth hormone secretion, as well as alterations in secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).48–52 However, the current study did not evaluate for endocrine function in HIV-infected children. Further investigation of the potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of attenuated statural growth among well-suppressed HIV-infected children is warranted.

This study has several strengths. By selecting participants from a large longitudinal cohort, we were able to investigate the extent of impaired mitochondrial markers in perinatally HIV-infected children mostly virally suppressed at the time of current study. All HIV-infected children had started ART early in life and had prolonged viral suppression, which allowed us to investigate the long-term impact of perinatal HIV infection and ART on mitochondrial impairment. Multiple mitochondrial markers involved in different aspects of mitochondrial function were measured, which make it possible to describe a wider range of mitochondrial dysfunction in this population. This study was limited by small sample sizes in subgroups of low or high mtDNA content and the single time point at which mitochondrial data were obtained. Another limitation is that some participants were missing VL and/or CD4 data at the time of marker measurement, requiring imputation from earlier visits. We did not observe any differences in the results if the imputed VL and CD4 counts/percentages were excluded, indicating that this method is reasonable. A major limitation is that we did not have information on cell composition, including platelet and white blood cell (WBC) counts. Platelets contain mtDNA molecules but no nDNA.53 Healthy subjects usually have 14–90 times more platelets than leukocytes.54 HIV infection may significantly reduce platelet and WBC counts.55 Therefore, we cannot definitively conclude that mitochondrial functioning per se, and not confounding by changes in blood cell composition, explains our observations. A recent study in adults presented estimates of associations between markers of mitochondrial function and HIV-related parameters both unadjusted and adjusted for counts of platelets and WBC. They observed that associations tended to be masked in unadjusted analyses, suggesting that failure to adjust for these parameters introduces biological variability that biases toward the null.55

In summary, our findings suggest that mitochondrial function, particularly as measured by CIV, indicative of respiratory function, does not reach levels seen in uninfected children despite prolonged suppression on ART. Moreover, CIV levels are lowest in those with stunting. In our study, prolonged treatment started at an early age improved mitochondrial function in perinatally-infected children. This suggests that even longer periods of ART than studied here may allow for almost complete recovery, but further investigation is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by funding from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD 073977, HD 073952). Results included in this article were presented at Conference at Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Boston, MA, March 4–7, 2018.

Author Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interests were disclosed by the authors.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Berti E, Thorne C, Noguera-Julian A, et al. : The new face of the pediatric HIV epidemic in Western countries: Demographic characteristics, morbidity and mortality of the pediatric HIV-infected population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34(Suppl 1):S7–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moren C, Noguera-Julian A, Garrabou G, et al. : Mitochondrial evolution in HIV-infected children receiving first- or second-generation nucleoside analogues. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crain MJ, Chernoff MC, Oleske JM, et al. : Possible mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with antiretroviral therapy use in children perinatally infected with HIV. J Infect Dis 2010;202:291–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu K, Sun Y, Liu D, et al. : Mitochondrial toxicity studied with the PBMC of children from the Chinese national pediatric highly active antiretroviral therapy cohort. PLoS One 2013;8:e57223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moren C, Garrabou G, Noguera-Julian A, et al. : Study of oxidative, enzymatic mitochondrial respiratory chain function and apoptosis in perinatally HIV-infected pediatric patients. Drug Chem Toxicol 2013;36:496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moren C, Noguera-Julian A, Rovira N, et al. : Mitochondrial assessment in asymptomatic HIV-infected paediatric patients on HAART. Antivir Ther 2011;16:719–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cossarizza A, Pinti M, Moretti L, et al. : Mitochondrial functionality and mitochondrial DNA content in lymphocytes of vertically infected human immunodeficiency virus-positive children with highly active antiretroviral therapy-related lipodystrophy. J Infect Dis 2002;185:299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noguera-Julian A, Moren C, Rovira N, et al. : Decreased mitochondrial function among healthy infants exposed to antiretrovirals during gestation, delivery and the neonatal period. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:1349–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosso R, Nasi M, Di Biagio A, et al. : Effects of the change from Stavudine to tenofovir in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: Studies on mitochondrial toxicity and thymic function. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saitoh A, Fenton T, Alvero C, et al. : Impact of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondria in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:4236–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pernas B, Rego-Perez I, Tabernilla A, et al. : Plasma mitochondrial DNA levels are inversely associated with HIV-RNA levels and directly with CD4 counts: Potential role as a biomarker of HIV replication. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:3159–3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arpadi SM: Growth failure in children with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;25(Suppl 1):S37–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feucht UD, Van Bruwaene L, Becker PJ, et al. : Growth in HIV-infected children on long-term antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health 2016;21:619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jesson J, Dahourou DL, Folquet MA, et al. : Malnutrition, growth response and metabolic changes within the first 24 months after ART initiation in HIV-infected children treated before the age of two years in West Africa. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;37:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andreux PA, van Diemen MPJ, Heezen MR, et al. : Mitochondrial function is impaired in the skeletal muscle of pre-frail elderly. Sci Rep 2018;8:8548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Merz TM, Pereira AJ, Schurch R, et al. : Mitochondrial function of immune cells in septic shock: A prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Niesen AM, Rossow HA: The effects of relative gain and age on peripheral blood mononuclear cell mitochondrial enzyme activity in preweaned Holstein and Jersey calves. J Dairy Sci 2019;102:1608–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kakiuchi C, Ishiwata M, Kametani M, et al. : Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial DNA deletions in the brains of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;8:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rooney JP, Ryde IT, Sanders LH, et al. : PCR based determination of mitochondrial DNA copy number in multiple species. Methods Mol Biol 2015;1241:23–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung N, Lehmann C, Knispel M, et al. : Long-term beneficial effect of protease inhibitors on the intrinsic apoptosis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in HIV-infected patients. HIV Med 2012;13:469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hulgan T, Kallianpur AR, Guo Y, et al. : Peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA copy number obtained from genome-wide genotype data is associated with neurocognitive impairment in persons with chronic HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;80:e95–e102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Masyeni S, Sintya E, Megawati D, et al. : Evaluation of antiretroviral effect on mitochondrial DNA depletion among HIV-infected patients in Bali. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2018;10:145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marsden MD, Zack JA: Neutralizing the HIV reservoir. Cell 2014;158:971–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rozzi SJ, Avdoshina V, Fields JA, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus promotes mitochondrial toxicity. Neurotox Res 2017;32:723–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Imamichi H, Dewar RL, Adelsberger JW, et al. : Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce novel protein-coding RNA species in HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:8783–8788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferri KF, Jacotot E, Blanco J, et al. : Mitochondrial control of cell death induced by HIV-1-encoded proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;926:149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang CY, Chiang SF, Lin TY, et al. : HIV-1 Vpr triggers mitochondrial destruction by impairing Mfn2-mediated ER-mitochondria interaction. PLoS One 2012;7:e33657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tahrir FG, Shanmughapriya S, Ahooyi TM, et al. : Dysregulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics and quality control by HIV-1 Tat in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Physiol 2018;233:748–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Avdoshina V, Fields JA, Castellano P, et al. : The HIV protein gp120 alters mitochondrial dynamics in neurons. Neurotox Res 2016;29:583–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baxter AE, O'Doherty U, Kaufmann DE: Beyond the replication-competent HIV reservoir: Transcription and translation-competent reservoirs. Retrovirology 2018;15:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saha JM, Liu H, Hu PW, et al. : Proteomic profiling of a primary CD4(+) T cell model of HIV-1 latency identifies proteins whose differential expression correlates with reactivation of latent HIV-1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2018;34:103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Margolis AM, Heverling H, Pham PA, et al. : A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol 2014;10:26–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jesson J, Koumakpai S, Diagne NR, et al. : Effect of age at antiretroviral therapy initiation on catch-up growth within the first 24 months among HIV-infected children in the IeDEA West African Pediatric Cohort. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:e159–e168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seth A, Malhotra RK, Gupta R, et al. : Effect of antiretroviral therapy on growth parameters of children with HIV infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;37:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jesson J, Leroy V: Challenges of malnutrition care among HIV-infected children on antiretroviral treatment in Africa. Med Mal Infect 2015;45:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Isanaka S, Duggan C, Fawzi WW: Patterns of postnatal growth in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed children. Nutr Rev 2009;67:343–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arpadi SM, Cuff PA, Kotler DP, et al. : Growth velocity, fat-free mass and energy intake are inversely related to viral load in HIV-infected children. J Nutr 2000;130:2498–2502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johann-Liang R, O'Neill L, Cervia J, et al. : Energy balance, viral burden, insulin-like growth factor-1, interleukin-6 and growth impairment in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS 2000;14:683–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guarino A, Bruzzese E, De Marco G, et al. : Management of gastrointestinal disorders in children with HIV infection. Paediatr Drugs 2004;6:347–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rondanelli M, Caselli D, Arico M, et al. : Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein 3 response to growth hormone is impaired in HIV-infected children. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2002;18:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Rossum AM, Gaakeer MI, Verweel S, et al. : Endocrinologic and immunologic factors associated with recovery of growth in children with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection treated with protease inhibitors. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Castro-Gago M, Gomez-Lado C, Perez-Gay L, et al. : Abnormal growth in mitochondrial disease. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. El-Hattab AW, Adesina AM, Jones J, et al. : MELAS syndrome: Clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Mol Genet Metab 2015;116:4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wolny S, McFarland R, Chinnery P, et al. : Abnormal growth in mitochondrial disease. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:553–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miller WL: Steroid hormone synthesis in mitochondria. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;379:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maechler P: Mitochondrial function and insulin secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;379:12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chow J, Rahman J, Achermann JC, et al. : Mitochondrial disease and endocrine dysfunction. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017;13:92–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hirschfeld S, Laue L, Cutler GB Jr., et al. : Thyroid abnormalities in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr 1996;128:70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwartz LJ, St Louis Y, Wu R, et al. : Endocrine function in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Dis Child 1991;145:330–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matarazzo P, Palomba E, Lala R, et al. : Growth impairment, IGF I hyposecretion and thyroid dysfunction in children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. Acta Paediatr 1994;83:1029–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lala R, Palomba E, Matarazzo P, et al. : ACTH and cortisol secretions in children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. Pediatr AIDS HIV Infect 1996;7:243–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frost RA, Nachman SA, Lang CH, et al. : Proteolysis of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in human immunodeficiency virus-positive children who fail to thrive. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:2957–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Urata M, Koga-Wada Y, Kayamori Y, et al. : Platelet contamination causes large variation as well as overestimation of mitochondrial DNA content of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Ann Clin Biochem 2008;45(Pt 5):513–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hurtado-Roca Y, Ledesma M, Gonzalez-Lazaro M, et al. : Adjusting MtDNA quantification in whole blood for peripheral blood platelet and leukocyte counts. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sun J, Longchamps RJ, Piggott DA, et al. : Association between HIV infection and mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood: A population-based, prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2019;219:1285–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.