Abstract

Mindfulness gained increased attention as it relates to aggressive behavior, including dating violence. However, no known studies examined how the combined influences of dispositional mindfulness and perceived partner infidelity, a well-documented correlate of dating violence, relate to women’s dating violence perpetration. Using a sample of college women (N = 203), we examined the relationship between perceived partner infidelity and physical dating violence perpetration at varying levels of dispositional mindfulness, controlling for the influence of alcohol use. Results indicated perceived partner infidelity and dating violence perpetration were positively related for women with low and mean dispositional mindfulness, but not for women with high dispositional mindfulness. These results further support the applicability of mindfulness theory in the context of dating violence. Implications of the present findings provide preliminary support for mindfulness intervention in relationships characterized by infidelity concerns.

Keywords: dating violence, domestic violence, intervention/treatment, predicting domestic violence

Physical dating violence (e.g., grabbing, pushing, slapping, hitting, beating up, or choking) committed against one’s intimate partner is a prevalent problem throughout U.S. college campuses. An estimated 20% to 45% of college students experienced at least one act of physical aggression within a romantic relationship each year (Luthra & Gidycz, 2006; Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008). Although men perpetrate more severe physical dating violence, with women sustaining more severe physical injuries, women endorse perpetrating physical dating violence more often than do men (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Misra, Selwyn, & Rohling, 2012). College students’ dating violence is more often characterized by bidirectional or female-only perpetration relative to male-to-female unidirectional perpetration (Orcutt, Garcia, & Pickett, 2005; Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012; Luthra & Gidycz, 2006). Despite the prevalence of female-perpetrated dating violence, existing literature primarily focused on men’s violence toward women (Barber, 2008; Drijber, Reijnders, & Ceelen, 2013).

Understanding risk and protective factors for female-perpetrated dating violence is essential for conceptualizing ways to reduce risk for victimized men. College men who are victimized by dating violence endorsed a variety of negative experiences including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, somatic complaints, substance use, and self-injury (Kaura & Lohman, 2007; Levesque, Lafontaine, Bureau, Cloutier, & Dandurand, 2010; Shorey, Rhatigan, Fite, & Stuart, 2011). Furthermore, intervention efforts are largely based on male-to-female perpetration theories, which may contribute to their poor efficacy when applied to women (Straus, 2011). Further research on malleable, adaptive skills relevant to women’s perpetration of dating violence would improve efforts to intervene with this prevalent social problem (Murphy & Meis, 2008; Shorey et al., 2012). The current study sought to explore this gap in the literature by examining dispositional mindfulness as a moderator of the relationship between perceived partner infidelity, a well-known correlate of dating violence, and college women’s dating violence perpetration.

Mindfulness and Aggression

Mindfulness is conceptualized as purposefully bringing one’s attention to the internal and external present-moment experiences in a non-judgmental way, oftentimes by means of meditation (Baer, 2003). When distressing cognitions, emotions, or physiological experiences arise, individuals are instructed to non-judgmentally approach the experience with curiosity and acceptance such that attention is self-regulated (Hayes & Feldman, 2004). With mindfulness, individuals gain distance from emotional experiences, which is believed to prevent avoidance of and over-engagement with emotions (Bowlin & Baer, 2012; Hayes & Feldman, 2004). In contrast to this multifaceted model of mindfulness described by Baer (2003), Brown and Ryan (2003) suggested individuals differ in their propensity to be attentive to internal and external events (i.e., dispositional mindfulness). These researchers assert that dispositional mindfulness is foundational for the development of other mindfulness practices (e.g., non-judgment and acting with awareness; Baer et al., 2008; Brown & Ryan, 2003). By bringing one’s attention to present-moment experiences, dispositional mindfulness is believed to reduce rumination and one’s attachment to thoughts, thereby facilitating emotion regulation as opposed to habitual reactivity to emotion-laden stimuli (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). In support of this theoretical model, Kiken and Shook (2012) discovered dispositional mindfulness reduces emotional distress, in part, by facilitating less negatively biased cognition. Given such benefits, it is not surprising dispositional mindfulness gained increased attention as a possible buffer for aggressive behavior (Fix & Fix, 2013).

Research suggested mindfulness protects against physical aggression by means of greater self-control, increased emotion regulation, decreased rumination, and fewer reactive impulses toward oneself and others (Borders, Earleywine, & Jajodia, 2010; Bowlin & Baer, 2012; Shorey, Seavey, Quinn, & Cornelius, 2014). Borders et al. (2010) and Heppner et al. (2008) found greater self-reported dispositional mindfulness related to decreased hostility and aggression within undergraduate populations. Heppner and colleagues (2008) then induced state mindfulness which resulted in decreased aggression following rejection. Despite the apparent benefits of mindfulness demonstrated in these studies, the role of dispositional mindfulness and violence within the context of a romantic relationship was not examined. Researchers have only recently begun to explore the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and aggression in intimate relationships (e.g., Shorey et al., 2012). Within romantic relationships, dispositional mindfulness related to increased relationship satisfaction and communication following conflict (Barnes, Brown, Krusemark, Campbell, & Rogge, 2007; Kozlowski, 2013). Qualitative data obtained from individuals in romantic relationships who underwent mindfulness-based training revealed mindfulness was related to improved abilities to be present with, as opposed to avoid, internal and external triggers for conflict, increased empathy and perspective-taking, and fewer frustration-driven habitual responses (Bihari & Mullan, 2014). Shorey and colleagues (2014) demonstrated dispositional mindfulness negatively related to undergraduate women’s partner-directed psychological and physical aggression. Thus, it is well-established that dispositional mindfulness is inversely related to aggression. However, no known study has examined dispositional mindfulness as a moderator of the relationship between perceived partner infidelity and physical aggression perpetration.

Perceived Infidelity and Dating Violence

Perceived partner infidelity, or suspicion that a partner was emotionally and/or sexually unfaithful during a romantic relationship, is a well-documented precipitating factor of dating violence (Babcock, Costa, Green, & Eckhardt, 2004; Follingstad, Bradley, Laughlin, & Burke, 1999; Haden & Hojjat, 2006; Kaighobadi, Shackelford, & Goetz, 2009). Researchers speculate violence toward a partner in response to infidelity functions to deter a partner from future extra-dyadic involvement (Buss, 2002). Although evolutionary theory posits violence in response to perceived infidelity is primarily perpetrated by men (Buss, 2002), empirical research suggests otherwise (DeSteno, Bartlett, Braverman, & Salovey, 2002; Kato, 2014). Kruttschnitt and Carbone-Lopez (2006) revealed that incarcerated women’s perception of a partner’s infidelity was the second-most identified motivation for perpetrating intimate partner violence. Within college populations, women and men endorsed similar emotional and behavioral responses, including physical aggression, in response to a partner’s infidelity (Haden & Hojjat, 2006; Luci, Foss, & Galloway, 1993). Furthermore, college students encounter abundant opportunities to become suspicious of and ruminate about a partner’s extra-dyadic involvement, which increases the likelihood of dating violence (Brem, Spiller, & Vandehey, 2015; Elphinston & Noller, 2011; Tokunaga, 2011). Understanding protective factors that interrupt this process will inform interventions for college women.

Dispositional mindfulness may be an important factor that protects against dating violence in the context of perceived partner infidelity. Based on mindfulness theory, a woman who is able to appropriately attend to emotions without getting caught up in them, avoiding them, or automatically reacting to them should be less likely to display aggression toward a partner. Furthermore, we should observe the protective function of dispositional mindfulness even in the context of emotion-laden situations, such as suspected infidelity.

Purpose and Hypotheses

Despite the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in various populations, the potential protective effect of dispositional mindfulness for college women who perceive a partner to be unfaithful is unknown. The present study sought to explore this gap in the literature by examining the cross-sectional relation between perceived partner infidelity and female-perpetrated dating violence at varying levels of dispositional mindfulness. We sought to examine these relations while controlling for the influence of alcohol use, as alcohol use is a well-established correlate for women’s dating violence perpetration, suspicion of infidelity, and efforts to escape awareness of present-moment, emotion-laden stimuli (Levin et al., 2012; Nemeth, Bonomi, Lee, & Ludwin, 2012; Shorey, Stuart, & Cornelius, 2011; Stappenbeck & Fromme, 2010).

We hypothesized dispositional mindfulness would moderate the relationship between perceived partner infidelity and physical assault such that perceived partner infidelity and physical assault perpetration would be positively related among women low in dispositional mindfulness. In contrast, we hypothesized that perceived partner infidelity and physical assault would not be related among women high in dispositional mindfulness.

Method

Participants

Only women who were 18 years old or above and in a romantic relationship for at least 1 month were eligible for the study. Two hundred and three undergraduate women enrolled in introductory psychology courses at a large, southeastern university completed an online battery of questionnaires for the present study. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 42 years (M = 19.16, SD = 2.22). The sample was primarily Non-Hispanic Caucasian (84.7%), followed by African American (9.2%), Asian American (4.8%), Hispanic/Latino (2.6%), Indian/Middle Eastern (.9%), Pacific Islander (.9%), and Native American (.4%). The majority of the sample identified as heterosexual (97.8%), followed by bisexual (1.7%), and lesbian (.4%). The mean relationship length was 11.98 months (SD = 13.68).

Measures

Physical assault.

Participants completed the perpetration items of the Physical Assault Subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003) to assess partner-directed physical assault within the past year. Responses to the 12 items (e.g., “I pushed or shoved my partner”) range from 0 (this never happened) to 6 (more than 20 times). Total physical assault scores were calculated by adding the midpoint for each item response (e.g., a “4” for the response “3–5 times”), with higher scores representing more frequent physical assault perpetration. Previous studies indicated the Physical Assault Subscale of the CTS2 has adequate internal consistency (Straus et al., 1996). The Physical Assault Subscale demonstrated adequate reliability in the present study (α = .83).

Mindfulness.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003) is a 15-item, self-report measure of dispositional mindfulness. Participants indicated the extent to which they experience 15 statements (e.g., “I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past”) with responses ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Scores are summed and divided by the total number of items, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of trait mindfulness. Existing literature supports the use of the MAAS in assessing mindfulness in undergraduate students and indicates the MAAS has adequate internal consistency (α = .82; Brown & Ryan, 2003). In the present study, the MAAS demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .93).

Perceived partner infidelity.

Ten items (see Table 1) were developed for this study to assess the extent to which women believed their partners engaged in infidelity during the course of their romantic relationship. Items were developed on the basis of existing literature examining jealousy-inducing situations within a romantic relationship (Brainerd, Hunter, Moore, & Thompson, 1996; S. M. Murphy, Vallacher, Shackelford, Bjorklund, & Yunger, 2006; Neal & Lemay, 2014). Infidelity acts ranged from less sexually explicit behaviors (e.g., “checked out or stared at an individual and/or individuals to whom they might be attracted”) to more sexually explicit acts (e.g., “engaged in anal intercourse with another individual(s) outside of the context of your relationship”). Response options were 0 (no) or 1 (yes). Items endorsed as happening were summed such that higher scores correspond to a greater number of perceived infidelity behaviors. The internal consistency coefficient (α = .81) indicated the 10 items demonstrated adequate internal consistency.

Table 1.

Percent of Women Who Reported Perceiving a Dating Partner Committing Acts of Infidelity.

| Item | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Checked out” or stared at an individual and/or individuals to whom they might be attracted | 56 |

| 2. | Engaged in flirting behavior with another individual and/or individuals | 50.9 |

| 3. | Developed romantic feelings for another individual and/or individuals | 10.6 |

| 4. | Spent time alone with an individual and/or individuals to whom they might be attracted for the purpose of becoming closer with them | 19.9 |

| 5. | Engaged in a close relationship, though not sexual, with somebody they were attracted to outside of the context of your relationship | 13.4 |

| 6. | Kissed or made out with another individual(s) outside of the context of your relationship | 13.9 |

| 7. | Cuddled or held hands with another individual and/or individuals outside of the context of your relationship | 9.3 |

| 8. | Engaged in oral intercourse with another individual(s) outside of the context of your relationship | 5.1 |

| 9. | Engaged in vaginal intercourse with another individual(s) outside of the context of your relationship | 7.4 |

| 10. | Engaged in anal intercourse with another individual(s) outside of the context of your relationship | 1.4 |

Alcohol use.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Asaland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) is a self-report measure used to assess women’s alcohol use in the year prior to participation in the present study. The AUDIT consists of 10 items, which examine the intensity and frequency of alcohol use, symptoms of alcohol tolerance and dependence, and negative consequences of alcohol use. The AUDIT demonstrated good reliability across multiple populations, including college students (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001; Shorey et al., 2014). The AUDIT demonstrated adequate reliability in the present study (α = .82).

Procedure

The institutional review board of the last author approved the procedures for the study. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study on a secure, online survey system prior to completing the questionnaires. Women were recruited from introductory psychology courses and participated to fulfill partial course requirements. Participants received credit for their participation and were provided with a list of referral sources following completion of the study.

Data Analytic Strategy

We conducted a hierarchical multiple regression using Hayes and Matthes’ (2009) macro to test the interaction between perceived partner infidelity and dispositional mindfulness predicting physical assault while controlling for alcohol use, a known correlate of both suspicion of infidelity and physical assault (Nemeth et al., 2012; Shorey et al., 2014). The Physical Assault Subscale was log-transformed prior to analyses due to positive skew and kurtosis. Physical Assault Subscale scores were entered as the criterion variable, perceived partner infidelity as the focal predictor, and mindfulness as the moderating variable. Alcohol use was entered as a covariate. All variables were mean centered to reduce multicollinearity (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). To explicate the interaction, we tested the relationship between partner-directed physical assault and perceived partner infidelity at high (+1 SD), mean, and low (−1 SD) levels of dispositional mindfulness.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables are displayed in Table 2. Bivariate correlations revealed women’s perceived partner infidelity positively related to alcohol use and physical assault perpetration. Dispositional mindfulness was negatively related to alcohol use and physical assault. A majority of the sample believed their partner “checked out” (56%) or flirted with (50.9%) another individual to whom they were attracted. Least-endorsed suspicions included believing a partner engaged in oral intercourse (5.1%) and anal intercourse (1.4%) with someone else (see Table 1). Results indicated the overall prevalence of physical assault in the current study was 25.9%.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Variables.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived infidelity | 1.88 | 2.10 | — | |||

| 2. Mindfulness | 4.04 | 0.10 | −.10 | — | ||

| 3. Alcohol use | 14.79 | 4.44 | .15* | −.17* | — | |

| 4. Physical assault | 3.87 | 10.24 | .21** | −.25** | .14* | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

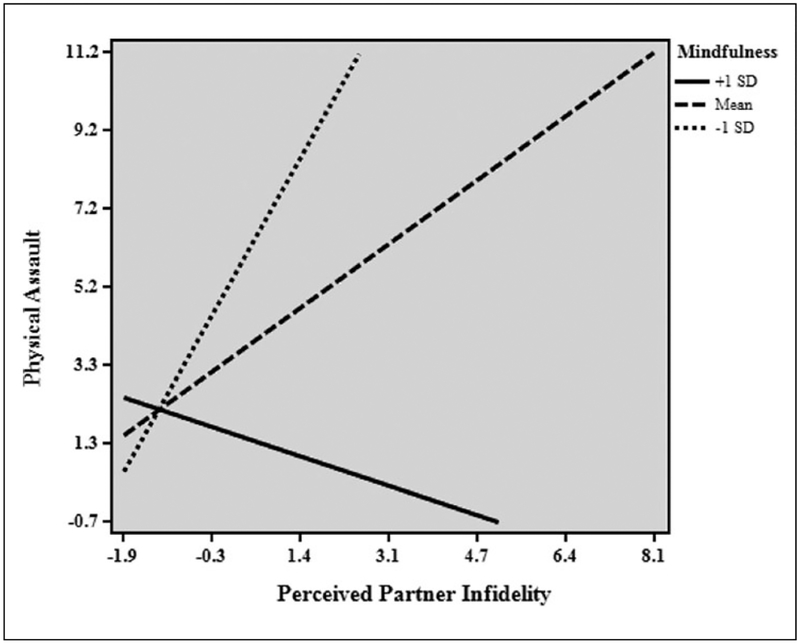

Moderation Analyses

Table 3 displays regression results. Our hypothesis was supported. Controlling for alcohol use, there was a significant main effect for perceived partner infidelity such that higher levels of perceived partner infidelity related to increased physical assault perpetration. There was a significant main effect for dispositional mindfulness such that lower levels of dispositional mindfulness related to increased physical assault perpetration controlling for the effects of alcohol use. Results of a two-way interaction between dispositional mindfulness and perceived partner infidelity controlling for alcohol use revealed the overall model fit was significant. The addition of the interaction term contributed to a significant increase in R2. Explication of this interaction evidenced a positive association between perceived partner infidelity and physical assault perpetration for women who endorsed low (B = 2.37, p < .001) and mean (B = .96, p = .004) levels of dispositional mindfulness. The relation between perceived partner infidelity and physical assault perpetration was not significant for individuals endorsing high levels of dispositional mindfulness (B = −.44, p = .36). Figure 1 displays a visual depiction of the interaction.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Women’s Physical Assault Perpetration in Romantic Relationships (n = 203).

| Predictor | R2 | ∆R2 | B | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .02 | 3.82 | .05 | ||

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Step 2 | .10 | .08 | 6.88*** | ||

| Alcohol use | 0.20 | .23 | |||

| Infidelity | 1.09** | .00 | |||

| Mindfulness | −1.61* | .03 | |||

| Step 3 | .18 | .08 | 10.29*** | .00 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.23 | .16 | |||

| Infidelity | 0.97** | .00 | |||

| Mindfulness | −1.76* | .01 | |||

| Mindfulness × Infidelity | −1.45*** | .00 |

Note. All continuous variables are centered.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Perceived partner infidelity is positively related to physical assault at low and mean levels of dispositional mindfulness.

To further characterize the nature of this interaction, we used the Johnson–Neymann (J-N; Johnson & Neymann, 1936) technique following the suggested procedures by Hayes and Matthes (2009). This technique allowed us to directly identify the exact level of dispositional mindfulness at which perceived partner infidelity demonstrated significant associations with physical assault perpetration (i.e., the regions of significance of the simple effects of dispositional mindfulness). This technique is accomplished by finding the value of dispositional mindfulness for which the ratio of the conditional effect to its standard error is equal to the critical t score. Results indicated perceived partner infidelity was significantly associated with increased likelihood of physical assault perpetration among women who reported total dispositional mindfulness scores greater than .40 SDs more negative than the mean, b = .67, SE = .34, t = 1.97, p = .05, but was unrelated to physical assault perpetration at higher levels of dispositional mindfulness. In other words, women who endorsed lower levels of dispositional mindfulness were more likely to endorse both infidelity concerns and physical assault perpetration relative to women who endorsed higher levels of dispositional mindfulness.

Discussion

Researchers only recently began to explore the role of mindfulness in populations affected by relationship aggression (Shorey et al., 2014). However, these studies did not consider dispositional mindfulness in the context of perceived partner infidelity, a known correlate of dating violence. Furthermore, limited data are available to demonstrate the protective utility of dispositional mindfulness for college women’s romantic relationships.

The present study examined the role of dispositional mindfulness in the context of perceived partner infidelity among college women, an understudied population at increased risk for dating violence. Consistent with our hypothesis, perceived partner infidelity was not related to partner-directed physical assault for women who endorsed higher levels of dispositional mindfulness. For women who endorsed low and average levels of dispositional mindfulness, perceived partner infidelity related to increased physical assault toward a partner. Results of the present study suggest mindful college women are less likely to be physically aggressive in romantic relationships even when concerns of infidelity are present.

This finding that dispositional mindfulness attenuated the impact of perceived partner infidelity on partner-directed physical assault is consistent with existing literature. Specifically, rumination, or getting caught up in one’s own thoughts, is believed to account for the link between perceived partner infidelity and relationship aggression (Elphinston, Feeney, Noller, Connor, & Fitzgerald, 2013). Because individuals who get caught up in their thoughts may allow their thoughts to influence their behaviors (Bartolo, Peled, & Moretti, 2009), it is conceivable that individuals who are better able to gain distance from their cognitions may choose more adaptive behavioral responses. Specific to infidelity, jealousy-related cognitions involve rumination about distrust, the need to engage in partner surveillance, and desire to control a partner, all of which are linked to physical dating violence (Carson & Cupach, 2000). Results of the present study provide direction for future research to determine whether dispositional mindfulness allows women to gain distance from these cognitions, which may interrupt the progression of suspicion of infidelity to physical dating violence.

Results of the present study are consistent with previous research supporting dispositional mindfulness as a buffer to interpersonal aggression (Borders et al., 2010; Heppner et al., 2008; Shorey et al., 2014). However, this is the only known study to consider the role of dispositional mindfulness for college women in the context of infidelity concerns. Because individuals with high dispositional mindfulness are better able to attend to emotional experiences, put their experiences into words, take a non-judgmental stance, and consciously respond to emotion-provoking situations (Bihari & Mullan, 2014; Bowlin & Baer, 2012), individuals who are low in dispositional mindfulness would be less able to appropriately communicate concerns with a partner in the context of conflict. Such individuals may have a limited repertoire of appropriate responses, criticize a partner’s behavior, act impulsively, and lack awareness of infidelity-related emotions (e.g., anger, fear, sadness, guilt, frustration, insecurity, and jealousy; Bevan, 2006). Indeed, the ability to interpret and label emotional experiences may inform the behavioral response an individual chooses (Brown & Ryan, 2003). In support of this notion, couples trained in mindfulness reported increased communication following conflict (Barnes et al., 2007). Furthermore, higher levels of dispositional mindfulness may translate into more adaptive anger management skills should conflict arise in a relationship (Shorey et al., 2014). Overall, our results support the applicability of mindfulness theory to college-aged populations, more specifically, college women.

Clinical Implications

Bidirectional correlations support a link between perceived partner infidelity and dating violence perpetration by college women. University clinicians should assess for the presence of dating violence when college women express infidelity concerns within romantic relationships. The present findings provide preliminary support for considering mindfulness as an intervention for romantic relationships where infidelity concerns are present. For example, clinicians may consider helping women achieve above-average levels of internal and external awareness to reduce the likelihood of violence occurring when suspicion of infidelity arises. It should be noted that no study examined a comprehensive, mindfulness-based intervention for dating violence. As opportunities to become suspicious of a partner’s fidelity become more abundant with the use of technology (e.g., social networking sites, smartphones, etc.; Brem et al., 2015; Elphinston & Noller, 2011; Tokunaga, 2011), intervention efforts will benefit from continued exploration of ways to intervene with the infidelity-dating violence relationship. Furthermore, because research supports a link between women’s dating violence perpetration and victimization (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012), dispositional mindfulness may moderate women’s risk for victimization. Future studies should consider the clinical utility of dispositional mindfulness as it relates to women’s experience of dating violence victimization.

Limitations

The present study has limitations which future research should address. First, the present study was of cross-sectional design; the temporal relationships between the variables are unknown. Future longitudinal studies should examine whether mindfulness reduces various forms of violence, including psychological aggression, in relationships characterized by infidelity. Second, we did not assess the frequency of a partner’s infidelity, or if participants believed their partners would be unfaithful in the future, which may influence the relationships among the variables. Similarly, participants were not asked to indicate relationship expectations (e.g., if they understood their relationship as monogamous, casual, or open), which may have implications for perceptions of partner infidelity. Future research should consider a more multifaceted approach to measuring both partner infidelity and relationship status in dating college students. Existing theory suggests jealousy-related distress and rumination follow suspicion of infidelity, which likely contributes to the likelihood of dating violence (Carson & Cupach, 2000; Kaighobadi et al., 2009). The present study did not assess if distress or rumination accompanied perceived infidelity, and therefore the mechanism by which dispositional mindfulness interrupts the relationship between perceived partner infidelity and dating violence is unknown. Additional research is needed to assess when, if, and for whom rumination follows suspicion of partner infidelity, as well as how dating violence and dispositional mindfulness relate to women’s relationship distress. Moreover, the present sample was relatively small, which likely reduced statistical power. Future studies should investigate the relationships among these variables using a larger, more representative sample and explore potential gender differences. Finally, the present study conceptualized dispositional mindfulness as a unitary construct whereas others recommend the need for a multifaceted construct (Baer, 2003). Future investigations should determine if similar results are obtained with alternative mindfulness models using methods of assessment beyond self-report.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, results of the present study provide insight into the relations between perceived partner infidelity, dispositional mindfulness, and physical dating violence among college women. Our findings contribute to the dating violence literature by considering moderators which may decrease the co-occurrence of physical dating violence and suspicion of infidelity among college students. The present study provides preliminary evidence for considering mindfulness-based interventions for this population.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported, in part, by Grant K24AA019707 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to the last author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Meagan J. Brem, MA, is a clinical psychology doctoral student at the University of Tennessee. She received her BA from Southwestern University and MA from Midwestern State University. Her research interests include risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence, including jealousy, mindfulness, and cyber abuse.

Caitlin Wolford-Clevenger, MS, is pursuing her PhD in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee–Knoxville. She received her BA and MS in psychology at the University of South Alabama. Her research interests focus on understanding and preventing the development of self- and other-directed aggression.

Heather Zapor, MA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee. She received her BA from the University of Akron. Her research interests include risk and resilience factors for intimate partner violence.

Joanna Elmquist, MA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee. She received her BA from Trinity University. Her research interests focus on family violence across the life span, including intimate partner violence and child maltreatment.

Ryan C. Shorey, PhD, is an assistant professor of psychology at Ohio University. His research focuses on intimate partner violence (IPV), particularly among dating couples, as well as the influence of substance use on IPV perpetration. He is also interested in the role of mindfulness-based interventions in improving substance use and IPV treatment outcomes.

Gregory L. Stuart, PhD, is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee–Knoxville and the Director of Family Violence Research at Butler Hospital. He is also an adjunct professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Babcock JC, Costa DM, Green CE, & Eckhardt CI (2004). What situations induce intimate partner violence? A reliability and validity study of the Proximal Antecedents to Violent Episodes (PAVE) scale. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 433–442. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JG, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S,… Williams JM (2008). Construct validity of the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber CF (2008). DV against men. Nursing Standard, 22(51), 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Brown KW, Krusemark E, Campbell WK, & Rogge RD (2007). The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33, 482–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolo T, Peled M, & Moretti MM (2009). Social-cognitive processes related to rick for aggression in adolescents. Court Review, 46, 44–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan JL (2006). Testing and refining a consequence model of jealousy across relational contexts and jealousy expression messages. Communication Reports, 19, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bihari J, & Mullan E (2014). Relating mindfully: A qualitative exploration of changes in relationships through mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Mindfulness, 5, 46–59. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0146-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Earleywine M, & Jajodia A (2010). Could mindfulness decrease anger, hostility, and aggression by decreasing rumination? Aggressive Behavior, 36, 28–44. doi: 10.1002/ab.20327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin SL, & Baer RA (2012). Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Brainerd EG, Hunter PA, Moore D, & Thompson TR (1996). Jealousy induction as a predictor of power and the use of other control methods in heterosexual relationships. Psychological Reports, 79(3, Pt. 2), 1319–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem MJ, Spiller LC, & Vandehey MA (2015). Online mate-retention tactics on Facebook are associated with relationship aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(16), 2831–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, & Creswell JD (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and its evidence for salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM (2002). Human mate guarding. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 23(4), 23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson C, & Cupach W (2000). Fueling the flames of the green-eyed monster: The role of ruminative thought in reaction to romantic jealousy. Western Journal of Communication, 64, 308–329. doi: 10.1080/10570310009374678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno D, Bartlett M, Braverman J, & Salovey P (2002). Sex differences in jealousy: Evolutionary mechanism or artifact of measurement? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1103–1116. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drijber BC, Reijnders UJ, Ceelen M (2013). Male victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Elphinston RA, Feeney J, Noller P, Connor J, & Fitzgerald J (2013). Romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction: The costs of rumination. Western Journal of Communication, 77, 293–304. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2013.770161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elphinston RA, & Noller P (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 631–635. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix RL, & Fix ST (2013). The effects of mindfulness-based treatments for aggression: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Bradley RG, Laughlin JE, & Burke L (1999). Risk factors and correlates of dating violence: The relevance of examining frequency and severity levels in a college sample. Violence and Victims, 14, 365–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden SC, & Hojjat M (2006). Aggressive responses to betrayal: Type of relationship, victim’s sex, and nature of aggression. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 101–116. doi: 10.1177/026540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, & Matthes J (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41 924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, & Feldman G (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 255–262. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner WL, Kernis MH, Lakey CE, Campbell WK, Goldman BM, Davis PJ, & Cascio EV (2008). Mindfulness as a means of reducing aggressive behavior: Dispositional and situational evidence. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 486–496. doi: 10.1002/ab.20258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, & Neymann J (1936). Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kaighobadi F, Shackelford TK, & Goetz AT (2009). From mate retention to murder: Evolutionary psychological perspectives on men’s partner-directed violence. Review of General Psychology, 13, 327–334. doi: 10.1037/a0017254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T (2014). Testing the sexual imagination hypothesis for gender differences in response to infidelity. BMC Research Notes, 7, Article 860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, & Lohman BJ (2007). Dating violence victimization, relationship satisfaction, mental health problems, and acceptability of violence: A comparison of men and women. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Kiken LG, & Shook NJ (2012). Mindfulness and emotional distress: The role of negatively biased cognition. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski A (2013). Mindful mating: Exploring the connection between mindfulness and relationship satisfaction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28, 92–104. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2012.748889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C, & Carbone-Lopez K (2006). Moving beyond the stereotypes: Women’s subjective accounts of their violent crime. Criminology, 44, 321–351. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Misra TA, Selwyn C, & Rohling ML (2012). Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse, 3, 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque C, Lafontaine M, Bureau J, Cloutier P, & Dandurand C (2010). The influence of romantic attachment and intimate partner violence on non-suicidal self-injury in young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ME, Lillis J, Seeley J, Hayes SC, Pistorello J, & Biglan A (2012). Exploring the relationship between experiential avoidance, alcohol use disorders, and alcohol-related problems among first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 60, 443–448. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.673522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luci P, Foss MA, & Galloway J (1993). Sexual jealousy in young men and women: Aggressive responses to partner and rival. Aggressive Behavior, 19, 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, & Gidycz CA (2006). Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, & Meis LA (2008). Individual treatment of intimate partner violence perpetrators. Violence and Victims, 23, 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Vallacher RR, Shackelford TK, Bjorklund DF, & Yunger JL (2006). Relationship experience as a predictor of romantic jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AM, & Lemay EP (2014). How partners’ temptation leads to their heightened commitment: The interpersonal regulation of infidelity threats. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 938–957. doi: 10.1177/026540751351274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth JM, Bonomi AE, Lee MA, & Ludwin JM (2012). Sexual infidelity as trigger for intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health, 21, 942–949. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Garcia M, & Pickett SM (2005). Female-perpetrated intimate partner violence and romantic attachment style in a college student sample. Violence and Victims, 20, 287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Asaland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction, 86, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, & Bell KM (2008). A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13, 185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Rhatigan DL, Fite PJ, & Stuart GL (2011). Dating violence victimization and alcohol problems: An examination of the stress-buffering hypothesis for perceived support. Partner Abuse, 2, 31–45. doi: 10.1891/19466560.2.1.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Seavey AE, Quinn E, & Cornelius TL (2014). Partner-specific anger management as a mediator of the relation between mindfulness and female perpetrated dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 4, 51–64. doi: 10.1037/a0033658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, & Cornelius TL (2011). Dating violence and substance use in college students: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Zucosky H, Brasfield H, Febres J, Cornelius TL, Sage C, & Stuart GL (2012). Dating violence prevention programming: Directions for future interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, & Fromme K (2010). A longitudinal investigation of heavy drinking and physical dating violence in men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2011). Gender symmetry and mutuality in perpetration of clinical-level partner violence: Empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2). Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, & Warren WL (2003). The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga RS (2011). Social networking site or social surveillance site? Understanding the use of interpersonal electronic surveillance in romantic relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]