Abstract

Objective:

Increasingly, serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications are prescribed in pregnancy. These medications pass freely into the developing fetus but little is known about their effect on brain development in humans. In this study we determine if prenatal maternal depression and SSRI medication change the EEG infant delta brush bursts which are an early marker of normal brain maturation.

Methods:

We measured delta brush bursts from the term infants of three groups of mothers (controls (N = 52), depressed untreated (N = 15), and those taking serotonin SSRI medication (N = 10). High density EEGs were obtained during sleep at an average age of 44 weeks post conceptional age. We measured the rate of occurrence, brush amplitude, oscillation frequency and duration of the bursts.

Results:

Compared to infants of control mothers, the parameters of delta brush bursts of the offspring of depressed and SSRI-using mothers are significantly altered: burst amplitude is decreased; the oscillation frequency increased, and the duration increased (SSRI only). These significant differences were found during both sleep states.

Conclusions:

Electrocortical bursting activity (i.e. delta brushes) is known to play an important role in early central nervous system (CNS) synaptic formation and function.

Significance:

Maternal depression or SSRI use may alter brain function in their offspring.

Keywords: Prenatal maternal depression, SSRI, Delta brush, EEG burst, Infant EEG

1. Introduction

The use of SSRI medications during pregnancy has increased many-fold over the last 30 years in response to the concerns about the effects of untreated psychiatric symptoms on both the mother and the gestating fetus. SSRIs administered during pregnancy initially enters the maternal bloodstream and then pass through the placenta into the fetal blood stream. At birth the infant serum levels are approximately one third of the maternal drug concentrations (Hendrick et al., 2003, Sit et al., 2011) While several studies indicate that SSRIs do not exert meaningful teratogenic effects, research on the consequences of these medications on fetal brain maturation has only recently been undertaken.

Preclinical studies in neonatal rodent models (equivalent to the third human trimester) indicate that SSRIs exert potent effects on brain circuitry that underlie subsequent delayed, peripubertal changes in behavior and cognition (Gingrich et al., 2017). Rodents exhibit a developmental sensitive period to SSRIs with changes to limbic circuitry. Around puberty, behaviors evocative of depression and anxiety appear and persist for the life of the animal.

Several studies have now examined offspring exposed to SSRIs during gestation with varying reports of adverse outcomes including elevated risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Clements et al., 2015), depression (Brown et al., 2016), and autism (Berard et al., 2016). SSRI administered during pregnancy initially enters the maternal blood stream and then passes through the placenta into the fetal blood stream. At birth, the infant serum levels are approximately one third of the maternal drug concentrations. Recent results from MRI studies of infants at 3–4 weeks of age show that both prenatal SSRI use and maternal depression alter brain structure and resting state connectivity (Posner et al., 2016, Lugo-Candelas et al., 2018). In addition, prenatal exposure to SSRIs was found to produce subtle EEG abnormalities in the exposed newborns including reduced interhemispheric connectivity and frontal activity at low-frequency oscillations and lower cross-frequency integration. These effects were not related to maternal depression or anxiety (Videman et al., 2017). Other characteristics of electrocortical activity that could provide early markers of alterations in brain development following these prenatal exposures have not been investigated.

In this current report we focus on a well described phenotype of early brain activity, oscillatory bursts of EEG known as delta brushes. Delta brushes are thought to be critical for establishing synaptic connections before, and in early months after, term birth (Arichi et al., 2017, Milh et al., 2007, Colonnese et al., 2010, Chipaux et al., 2013, Kaminska et al., 2017). These bursts of electrocortical activity are characterized by distinctive high frequency oscillations of 8–20 Hz activity (i.e. brushes) superimposed on low frequency, 1–3 Hz delta activity. These distinctive patterns of EEG begin at ~30 weeks post conceptional age (PCA) with the highest rate per minute at ~35 weeks and lasting until ~44 weeks postconceptional age (Chan et al., 2010).

As a component of the above-mentioned MRI studies (Posner et al., 2016, Lugo-Candelas et al., 2018) in a subset of these subjects we recorded high density (128 lead) EEGs and examined whether SSRIs and/or maternal depression altered the number or characteristics of delta brushes between 42 and 51 weeks postconceptional age. The offspring of three groups of women were assessed: those who were not depressed nor taking SSRI during pregnancy (healthy controls), those who were depressed but did not take SSRIs, and those who were taking SSRIs.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

The New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board approved all procedures and participants provided written informed consent. Participants received financial compensation for their participation. Data were collected between January 6, 2011, and October 26, 2016. Participants (pregnant women, aged 18–45 years) were recruited through obstetricians, midwives, and psychiatrists. 77 infants had a 1-hour EEG study between 42 and 50 weeks postconceptional age: 52 were in the normal control group, 15 in the depressed group and 10 in the SSRI exposed group. Group membership was determined after mothers completed a prenatal mood and medication assessment (between 19 and 39 weeks of gestation). Mothers were assigned to the depression group if their prenatal depressive symptom score on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale was equal to or greater than 16. Mothers were assigned to the SSRI group if they self-reported receiving any SSRI medication at some point in their pregnancy.

Of the 77 infants that provided EEG data for these analyses, 74 had data during active sleep, 64 during quiet sleep, 61 with data in both sleep states. Table 1 presents characteristics of the study infants and their mothers as well the depressive symptom scores (CED-D) for the three groups. There were significant group differences found for maternal age (from ANOVA, p < 0.001), years of mother’s education (from ANOVA, p < 0.001), and distribution across ethnicity and race groups (from X2, p < 0.01). Post-hoc tests showed that mothers in the depressed group were younger than those in either the control (p < 0.05) or SSRI groups (p < 0.001). Mothers in the SSRI group had more years of education than either the control (p < 0.01) or depressed (p < 0.001) groups. Paralleling differences in education, significant group differences were found for the distribution of incomes across groups (overall p < 0.01; control vs SSRI, p < 0.05; SSRI vs depressed), With regard to ethnicity/race categories, infants in the SSRI group differed from those in the control (p < 0.01) and depressed (p < 0.01) groups; no SSRI infants were from Hispanic mothers. There were, as expected, group differences in CES-D (Radloff, 1991) scores; all groups differed from each other, p < 0.05 or better.

Table 1.

Subject demographics.

| Characteristic | SSRI | Depressed | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 10 | 15 | 52 |

| Birth gestational age, wk, mean (SD) | 39.2 (0.9) | 39.5 (1.2) | 39.5 (1.0) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3032 (445) | 3354 (431) | 3344 (413) |

| Test postnatal age, wk, mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.9) | 5.7 (1.8) | 6.3 (2.2) |

| Sex (Male n:Female n) | 3:7 | 5:10 | 26:26 |

| Maternal age, y (mean, SD) | 34.0 (3.4) | 26.0 (5.6) | 30.4 (5.5) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||

| Black/African American | 1 | 3 | 15 |

| White | 9 | 2 | 15 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 9 | 19 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total Family Income, $ (1 control, missing) | |||

| 0–15,000 | 0 | 9 | 10 |

| >15,000–25,000 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| >25,000–50,000 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| >50,000–100,000 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| >100,000–250,000 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| >250,000 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Maternal CES-D, prenatal (mean, SD) (score < 16 is not depressed) | 14.3 (14.4) | 23.6 (6.8) | 7.5 (4.0) |

2.2. EEG data collection

Sleeping, non-sedated infants underwent an EEG study. As all infants were more than 2 weeks post birth minimizing potential residual SSRI drug effects and withdrawal symptoms (Forsberg et al., 2014). The recordings were collected during natural infant sleep with a 128 lead EEG system (Electrical Geodesics Inc.) sampled at 1000 samples per second. The studies of approximately 1-hour duration were processed by a custom MATLAB (Math Works, USA) algorithm that excluded data artifact (Grieve et al., 2003) and then detected and measured parameters of the EEG bursts as discussed below. In brief, neonate EEG data were processed in 30 second epochs and re-referenced to the average reference. In each epoch, data from an EEG lead (“channel”) was deemed to contain artifact if the voltage was greater than 50 microvolts rms and then the channel removed from further analysis. If more than 20% of the 128 EEG channels contained artifact the entire epoch was discarded as the requirement for a valid average reference was not met (Grieve et al., 2003). No data were interpolated across channels. Infant sleep state was determined from respiration data recorded simultaneously with the EEG using an automated sleep coding method (Isler et al., 2016).

2.3. Delta brush detection algorithm

Data were processed in 30 second epochs. In each 30 second epoch, high frequency bursts (8–20 Hz) in the EEG were detected by the amount of their high frequency power as this feature is the characteristic that defines them as different from background EEG as described previously (Myers et al., 2012). In brief, a time-varying spectrum was calculated for each 30 s epoch using multiple FFTs with a sliding 250 time-sample window that overlapped by one data sample and yielded a frequency resolution of ~4 Hz. The 10th percentile of the sum of power in the spectral time series between 8 and 20 Hz was computed in a sliding 0.5 s window, and then smoothed with a 2 Hz low pass filter to reduce potential EKG artifact. The data smoothed with a 2 Hz low pass filter were the time series of the power in the 8–20 Hz band and not the EEG waveform data. As the neonatal pulse rate is approximately 2 Hz, smoothing prevented the false “triggering” of burst indications from narrow EKG R-waves. The spectrum of the 8–20 Hz band power of a one-second duration burst is about 1 Hz wide and passes through the low pass filter. The choice of the 8–20 Hz detection bandwidth was adopted based on review of the literature describing high frequency oscillations in infant EEG (André et al., 2010, Milh et al., 2007, Tolonen et al., 2007). Within each epoch, the beginning of a burst was identified as the time at which the 10th percentile of the smoothed 8–20 Hz power time series was exceeded and ended when it dropped below the 10th percentile.

After identifying the occurrence of bursts from the smoothed, low pass filtered tracing, each burst was characterized by its duration in seconds (i.e. time above the 10th percentile). The EEG system had a hardware high pass filter at 0.01 Hz. We collected and measured the amplitude of the slow (“delta”) wave and the “fast” (brush) oscillation. Then, from the raw EEG signal the high frequency amplitude zero to peak (microvolts) and the frequency of the oscillation (i.e. the frequency of the spectral peak with highest power) were quantified. In addition, the number of bursts per minute (rate) was computed. All four parameters characterizing bursts were measured for all epochs of active and quiet sleep.

All EEG channels were analyzed in each 30 second epoch. There are actually 129 rather than 128 as we used the average reference to obtain the EEG data for the “reference channel” at Cz. We averaged burst data for all the leads contained in each spatial region. Details of the leads contained in each spatial region and a map of the regions is provided in our previous publications (Myers et al., 2015).

We took care to not conflate computer-detected delta brushes with Infant sleep spindles which have an oscillation frequency of 11–15 Hz and occur only during non-REM (NREM) sleep (see Methods). Spindles first appear at 44 weeks and are longer (2–4s) in duration than delta brushes (Ellingson, 1982, Metcalf, 1970, Lindemann et al., 2016). It is unlikely that we mistakenly identified sleep spindles as delta brushes at ages greater than 44 weeks. By definition bursts less than 2 seconds in duration are characteristic of delta brushes and not of spindles. The average burst duration was 0.81 s in both sleep states.

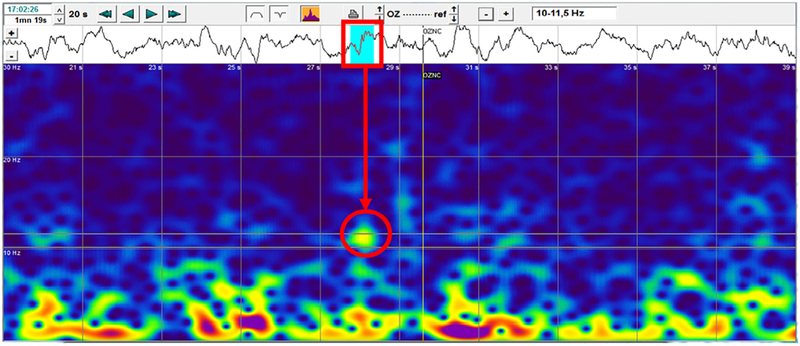

Fig. 1 is a wavelet power spectrum obtained using the Coherence software package from Natus Corporation. Shown is a 20 s segment of EEG from subject 2001 (42 weeks PMA) on lead Oz with a burst (red rectangle) with a brush oscillation spectrum of center frequency ~10.5 Hz (red circle). The spectral plot horizontal axis is 20 s and vertical axis is 0–30 Hz. The burst spectrum has a yellow area showing a brush oscillation spectrum with frequency spread between 10.00–11.50 Hz (indicated in panel upper right) which is correct for a delta brush as its “brush” has an oscillation frequency between 8 and 20 Hz and duration between 0.3 and 2 s. This burst has duration about 0.5 s. Below the yellow “brush” spectral area there is a “gap” in the spectrum (blue region) indicating little/no power at these frequencies and then a red region below approximately 5 Hz showing the power of the delta component. This “two-frequency” pattern is the unique spectral signature of the delta brush and is used by the computer algorithm in its analysis of the EEG time series waveform and spectral plot to discriminate the delta brush from other oscillatory bursts with frequency between 10.25 and 11.75 Hz (blue regions on EEG trace).

Fig. 1.

Delta brush power spectrum.

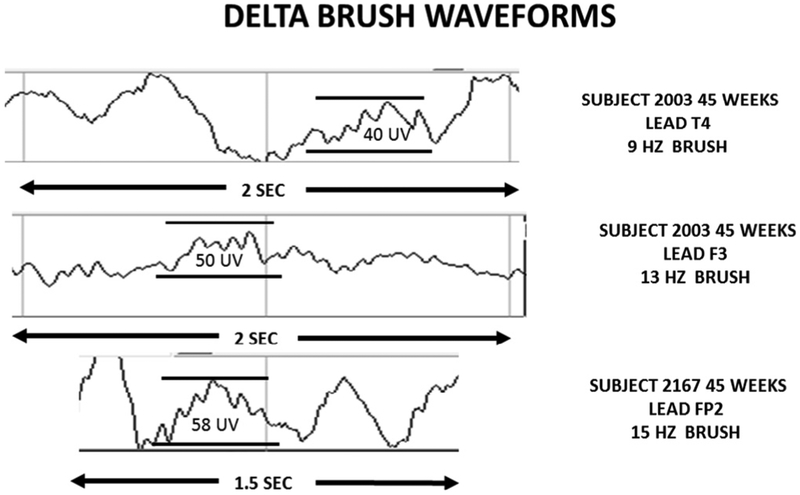

Fig. 2 shows the EEG traces of several delta brushes to illustrate their appearance.

Fig. 2.

Delta brush EEG waveforms.

2.4. Statistical analyses

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine group (control, depressed, and SSRI) differences in the average values of the four burst parameters – rate per minute (rate), amplitude (zero to peak) of high frequency component (amplitude), oscillatory frequency of the burst (frequency) and burst width (duration). Each of these analyses controlled for age (PCA) at the time of the EEG assessment, race/ethnicity and sex. In total, 96 analyses were conducted; 4 burst parameters ×12 spatial regions (left and right frontal polar, frontal, temporal, central, parietal, and occipital) × 2 sleep states (active and quiet) sleep states. When significant (p < 0.05) differences among groups were found, post-hoc (Tukey) tests for pairwise group differences were conducted. In addition, p-values for the overall (main) effect of group from the ANOVAs that passed a False Discovery Rate threshold of 10% were also identified. A liberal 10% FDR threshold was chosen because, at least with regard to effects of SSRI (n = 10 in AS, n = 8 in QS), we viewed these results as somewhat preliminary and wanted to identify possible group differences that would warrant confirmation in follow-up studies.

3. Results

The p-values from the ANOVA analyses above are presented in Table 2. For the 96 tests performed (12 regions 4 burst parameters × 2 states), 16 had significant differences (p < 0.05) group differences in delta brush characteristics. To further characterize these significant differences, pairwise post-hoc tests were performed.

Table 2.

Results from ANOVAs (p-values) for the main effect of group (control, depression, SSRI) on 4 parameters of delta brushes (rate per minute (rate), amplitude of high frequency component (ampl), burst duration, i.e. width (width), and frequency of the high frequency oscillation (freq). Results are given for each of 12 brain regions in each of two sleep states (Active and Quiet). ANOVAs included age at EEG assessment, sex and race/ethnicity (4 groups) as covariates LFP = left frontal polar, RFP = right frontal polar, LF = left frontal, RF = right frontal, LC = left central, RC = right central, LT = left temporal, RT = right temporal, LP = left parietal, RP = right parietal, LO = left occipital, RO = right occipital. p-values < 0.05 are shaded in green and p-values passing the 10% FDR threshold are shaded in yellow.

| Active Sleep | Quiet Sleep | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (49 controls, 15 depressed, 10 ssri) | (43 controls, 13 depressed, 8 ssri) | |||||||

| region | rate | ampl | width | freq | rate | ampl | width | freq |

| LFP | 0.161 | 0.839 | 0.259 | 0.070 | 0.333 | 0.542 | 0.109 | 0.170 |

| RFP | 0.137 | 0.686 | 0.508 | 0.041 | 0.443 | 0.773 | 0.088 | 0.271 |

| LF | 0.458 | 0.645 | 0.225 | 0.001 | 0.441 | 0.759 | 0.633 | 0.117 |

| RF | 0.182 | 0.282 | 0.625 | 0.002 | 0.340 | 0.931 | 0.119 | 0.140 |

| LC | 0.685 | 0.197 | 0.722 | 0.415 | 0.543 | 0.913 | 0.012 | 0.207 |

| RC | 0.478 | 0.086 | 0.466 | 0.030 | 0.823 | 0.642 | 0.125 | 0.703 |

| LT | 0.346 | 0.172 | 0.272 | 0.099 | 0.205 | 0.978 | 0.033 | 0.010 |

| RT | 0.436 | 0.149 | 0.619 | 0.020 | 0.443 | 0.622 | 0.085 | 0.121 |

| LP | 0.769 | 0.112 | 0.953 | 0.152 | 0.811 | 0.629 | 0.371 | 0.162 |

| RP | 0.694 | 0.041 | 0.167 | 0.005 | 0.758 | 0.366 | 0.049 | 0.591 |

| LO | 0.511 | 0.041 | 0.982 | 0.084 | 0.831 | 0.500 | 0.914 | 0.002 |

| RO | 0.539 | 0.049 | 0.282 | 0.009 | 0.677 | 0.488 | 0.613 | 0.006 |

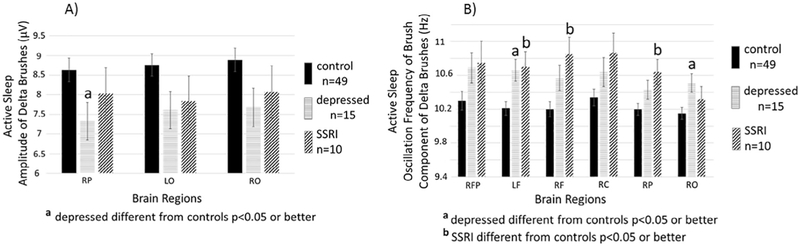

Fig. 3, left panel, depicts in the Active Sleep state, the means and SEs for the three regions (RP, LO and RO) where there were significant group effects for the amplitude parameter. Results from post-hoc tests show that burst amplitudes in infants whose mothers were depressed during pregnancy were significantly lower in all 3 regions than for infants of healthy controls. The mean values for burst amplitudes for infants whose mothers took SSRIs were lower than controls but these differences were not significant. Amplitudes of the depressed and SSRI groups were similar and not significantly different.

Fig. 3.

Active Sleep. LEFT PANEL. Shown are means (±SE) of zero to peak amplitudes in microvolts of the high frequency oscillation component of delta brushes detected during active sleep in infants of mothers without depression or SSRIs during pregnancy (control n = 49, solid black bars), infants of mothers who were depressed during pregnancy but did not take SSRIs (depressed n = 15, striped bars), and infants of mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy (SSRI n = 10, hatched bars). Results are shown for the three brain regions that demonstrated a main effect of group (control, depressed, SSRI) in ANOVAs (see Table 2). Superscript “a” above the bar indicates significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tukey’s) for the comparison between depressed and control. RP = right parietal, LO = left occipital, RO = right occipital. RIGHT PANEL. Shown are means (±SE) of the central frequency within the high frequency component of delta brushes detected during active sleep infants of mothers without depression or SSRIs during pregnancy (control n = 49, solid black bars), infants of mothers who were depressed during pregnancy but did not take SSRIs (depressed n = 15, striped bars), and infants of mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy (SSRI n = 10, hatched bars). Results are shown for the six brain regions that demonstrated a main effect of group (control, depressed, SSRI) in ANOVAs (see Table 2). Superscript “a” above the bar indicates significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tuckey’s) for the comparison between depressed and control and a superscript “b” indicates a significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tukey’s) for the comparison between SSRI and control. RFP = right frontal polar, LF = left frontal, RF = right frontal, RC = right central, RP = right parietal, RO = right occipital.

Fig. 3, right panel, depicts in Active Sleep state, the oscillation frequency of the high frequency component of delta brushes. Group differences were significant in 7 regions (RFP, LF, RF, RC, RT, RP, RO). Post-hoc analyses of these regions revealed that in 5 of the 7 regions (LF, RF, RP, RT, RO) the oscillation frequency of bursts was higher in depressed or SSRI exposed infants than infants of healthy control mothers.

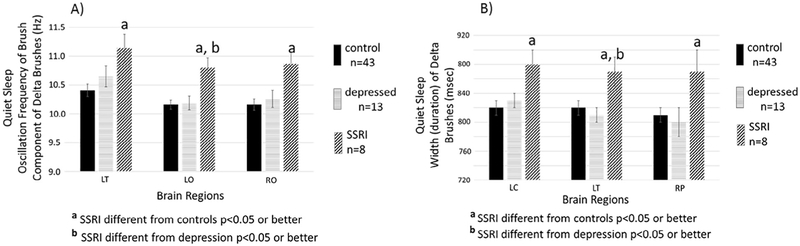

Fig. 4, left panel, for the Quiet Sleep state, shows significant group differences in the frequency of delta brushes in 3 brain regions (LC, LO, RO). Post-hoc tests revealed that in all 3 of these regions, infants of SSRI mothers had significantly higher frequency bursts than infants of healthy controls or of infants of depressed mothers. Burst frequencies were not significantly different between the control and depressed groups in any brain region.

Fig. 4.

Quiet Sleep. LEFT PANEL. Shown are means (±SE)) of the central frequency within the high frequency component of delta brushes. Detected during quiet sleep for infants of mothers without depression during pregnancy (control n = 43, solid black bars), infants of mothers who were depressed during pregnancy but did not take SSRIs (depressed n = 13, striped bars), and infants of mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy (SSRI n = 8, hatched bars). Results are shown for the three brain regions that demonstrated a main effect of group (control, depressed, SSRI) in ANOVAs (see Table 2). Superscript “a” above the bar indicates significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tukey’s) for the comparison between SSRI and control and a superscript “b” indicates a significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tukey’s) for the comparison between SSRI and depression. LT = left temporal, LO = left occipital, RO = right occipital. RIGHT PANEL. Shown are means (±SE) for the widths (i.e. duration) of delta brushes detected during quiet sleep of infants of mothers without depression or SSRIs during pregnancy (control n = 43, solid black bars), infants of mothers who were depressed during pregnancy but did not take SSRIs (depressed n = 13, striped bars), and infants of mothers who took SSRIs during pregnancy (SSRI n = 8, hatched bars). Results are shown for the three brain regions that demonstrated a main effect of group (control, depressed, SSRI) in ANOVAs (see Table 2). Superscript “a” above the bar indicates significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tuckey’s) for the comparison between SSRI and control and a superscript “b” indicates a significant (p < 0.05) post-hoc test (Tuckey’s) for the comparison between SSRI and depression. LC = left central, LT = left temporal, RP = right parietal.

Fig. 4, right panel, for the Quiet Sleep state, shows significant group differences in the duration of delta brushes in 3 brain regions (LC, LT, RP). Post-hoc tests revealed that in all 3 of these regions, infants of SSRI mothers had significantly wider bursts than infants of healthy controls or infants of depressed mothers. Burst durations were not significantly different between the control and depressed groups in any brain region.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure EEG delta brush activity in infants of depressed and SSRI-medicated mothers. We speculate that alterations in delta brush characteristics could be a marker of abnormal central nervous system (CNS) development as early as 6 weeks postnatally. Our results show that there is a significant effect of these prenatal exposures to maternal depression and/or SSRI use on the amplitude, frequency and duration of delta brushes but not on their rate of occurrence. We did find other regionally specific effects (See Figs. 2 and 3):

In Active Sleep:

-

Maternal depression and SSRI (compared to controls) caused

delta brush amplitude to be significantly decreased

delta brush frequency to be significantly increased

In Quiet Sleep:

-

SSRI use, and not depression, caused significant differences

delta brush duration was significantly increased

delta brush frequency was significantly increased

Prenatal maternal depression and/or SSRI use has several possible adverse outcomes for offspring including elevated risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Clements et al., 2015), depression (Brown et al., 2016), and autism (Berard et al., 2016). Prenatal maternal psychiatric symptoms also are associated with compromised neurobehavioral development of the offspring (Grote et al., 2015). Based on our results, we speculate that prenatal maternal depression and/or prenatal maternal use of SSRI medication might produce the above long-term effects by altering the delta brush parameters as described above.

Serotonin (5-HT) is one of brain’s chief neural neurotransmitters that is widely used in neural connections and signaling and circulates in the fetal bloodstream and brain. Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of drugs used for depression medication that are “selective” as they primarily affect serotonin, but not other neurotransmitters, increasing available serotonin at the synapse and reducing depressive symptoms. The reduced neuronal uptake of serotonin increases the transmitter in the synaptic cleft which can help to relieve depression (Barnes and Sharp, 1999, Herlenius and Lagercrantz, 2004). Administering SSRI to newborn rats in infancy led to increases in depressive and anxious-like behaviors as adults (Ansorge et al., 2004). This, and other results, have led to concern regarding the use of SSRIs as a treatment for depression during human pregnancy (Gingrich et al., 2017). Based on animal studies, delta brushes are similar in origin and function to “spindle bursts” and arise from thalamocortical/subplate circuit activity (Murata and Colonnese, 2019). The amplitude of spindle bursts in infant rats have been shown to be reduced by an intraperitoneal injection of a commonly used SSRI, citalopram (Akhmetshina et al., 2016). Importantly, CNS serotonin may be increased by untreated maternal depression. Maternal depression causes a reduction in MAO A, an enzyme present in the placenta, which breaks down serotonin and decreases the level in the infant. Thus, infants of mothers with untreated depression would, like infants exposed to SSRIs, have elevated levels of serotonin (Blakeley et al., 2013). The finding of lower amplitude delta brushes in active sleep may be related to the prenatal exposure to elevated levels of serotonin, however it is unclear why this effect is seen only in active sleep.

The literature shows a relationship between depression and changes in the insula of the depressed adults (Yin et al., 2018). Interestingly, offspring of depressed mothers showed increased functional connectivity of the amygdala with the left temporal cortex and insula similar to that observed in adults with major depressive disorder (Qiu et al., 2015). Further, right insular volume expansion and increased white matter structural connectivity with the right amygdala were also shown in infants of mothers who used SSRI medication during pregnancy (Lugo-Candelas et al., 2018). Hence another possible cause of delta brush alteration resulting from maternal depression and/or SSRI medication may be mediated by changes in the insula. Consistent with this hypothesis the insula is the location of the major fMRI bold signal activity associated with delta brush occurrence (Arichi et al., 2017). At this point it is not understood why changes in either connectivity or volume of the insula should alter the parameters of delta brushes selectively. This is a potential avenue for translational research. A limitation in comparing our behavioral-state related results with previous fMRI functional results for delta brush activity (Barnes and Sharp, 1999, Posner et al., 2016, Arichi et al., 2017) is that behavioral state was not noted in these prior studies.

Finally, as delta brushes are a key marker of infant neurodevelopment and synapse formation (Whitehead et al., 2017) the changes discussed here show that these important processes might be affected. We speculate that decreases in delta brush amplitude and increases in oscillation frequency and duration would serve as early markers for possible infant neurodevelopmental problems. Whitehead showed that frequency and amplitude decrease from 34 weeks to term age. No variation in width with age was mentioned. The increases in amplitude and frequency found here may indicate delayed maturation (Whitehead et al., 2017).

These early results do not enable us to address mechanisms or recommendations for treatment of prenatal maternal depression. As this is the first study showing substantial differences in delta brushes related to maternal depression, correlations with the long-term neurodevelopmental status of offspring of mothers with untreated depression and/or SSRI administration needs to be undertaken. Further, as our infant studies took place several weeks after birth, it is possible that factors in the postpartum environment could have affected the burst measurements. However, as the mean age of the infant at EEG was less than 6 weeks postnatal age, it is unlikely that this period of exposure had a significant effect compared to the duration of the pregnancy. Finally, our subject numbers (10) for SSRI users were small and need to be increased for future studies of SSRI effects. We are not able to postulate a “mechanism” by which the delta brush changes observed were causal or related to eventual neurodevelopmental deficits of the offspring. It may be that earlier delta brush characterization at birth paired with neurodevelopmental testing later in development will facilitate our understanding of the developmental mechanisms.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Prenatal exposure to maternal depression alters characteristics of EEG bursting activity during infancy.

Exposure to serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) during pregnancy also alters characteris tics of EEG bursting activity during infancy, but differently than maternal depression.

Assessment of infant EEG bursting activity affords a new early life marker for changes in brain development caused by maternal depression and/or SSRI use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sackler Institute of Developmental Psychobiology at Columbia University and by NIH grants R37 HD032774 and P50 MH090966 issued by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Akhmetshina D, Zakharov A, Vinokurova D, Nasretdinov A, Valeeva G, Khazipov R. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram suppresses activity in the neonatal rat barrel cortex in vivo. Brain Res Bul 2016;124:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André M, Lamblin MD, d’Allest AM, Curzi-Dascalova L, Moussalli-Salefranque F, Nguyen Thetich S, et al. Electroencephalography in premature and full-term infants. Developmental features and glossary. Neurophysiol Clin 2010;40(2):59–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science 2004;306 (5697):879–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arichi T, Whitehead K, Barone G, Pressler R, Padormo F, Edwards AD, et al. Localization of spontaneous bursting neuronal activity in the preterm human brain with simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Elife 6;2017:pii: e27814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function.Neuropharm 1999;38(8):1083–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berard A, Boukhris T, Sheehy O. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and autism: additional data on the Quebec Pregnancy/Birth Cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(6):803–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley PM, Capron LE, Jensen AB, O’Donnell KJ, Glover V. Maternal prenatal symptoms of depression and down regulation of placental monoamine oxidase A expression. J Psychosom Res 2013;75(4):341–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Gyllenberg D, Malm H, McKeague IW, Hinkka-Yli-Salomaki S, Artama M, et al. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure during pregnancy with speech, scholastic, and motor disorders in offspring. JAMA Psychiat 2016;73(11):1163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW, Yamazaki M, Akiyama T, Chu B, Donner EJ, Otsubo H. Rapid oscillatory activity in delta brushes of premature and term neonatal EEG. Brain Dev 2010;32(6):482–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipaux M, Colonnese MT, Mauguen A, Fellous L, Mokhtari M, Lezcano O, et al. Auditory stimuli mimicking ambient sounds drive temporal “delta-brushes” in premature infants. PLoS One 2013;8(11) e79028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR, Rosenfield HR, Murphy SN, Fava M, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiat 2015;20(6):727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnese MT, Kaminska A, Minlebaev M, Milh M, Bloem B, Lescure S, et al. A conserved switch in sensory processing prepares developing neocortex for vision. Neuron 2010;67(3):480–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson RJ. Development of sleep spindle bursts during the first year of life. Sleep 1982;5(1):39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L, Navér L, Gustafsson LL, Wide K. Neonatal adaptation in infants prenatally exposed to antidepressants- clinical monitoring using neonatal abstinence score. PLoS One 2014;9(11) e111327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JA, Malm H, Ansorge MS, Brown A, Sourander A, Suri D, et al. New insights into how serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors shape the developing brain. Birth Defects Res 2017;109(12):924–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve PG, Emerson RG, Fifer WP, Isler JR, Stark RI. Spatial correlation of the infant and adult electroencephalogram. Clin Neurophysiol 2003;114(9):1594–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, et al. Collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: a randomized trial. Depress Anxiety 2015;32(11):821–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick V, Stowe ZN, Altshuler LL, Hwang S, Lee E, Haynes D. Placental passage of antidepressant medications. Am J Psychiat 2003;160(5):993–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlenius E, Lagercrantz H. Development of neurotransmitter systems during critical periods. Exp Neurol 2004;190:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isler JR, Thai T, Myers MM, Fifer WP. An automated method for coding sleep states in human infants based on respiratory rate variability. Dev Psychobiol 2016;58(8):1108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska A, Delattre V, Laschet J, Dubois J, Labidurie M, Duval A, et al. Cortical auditory-evoked responses in preterm neonates: revisited by spectral and temporal analyses. Cereb Cortex 2017;28(10):3429–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann C, Ahlbeck J, Bitzenhofer SH, Hanganu-Opatz IL. Spindle activity orchestrates plasticity during development and sleep. Neural Plast 2016;2016:5787423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Candelas C, Cha J, Hong S, Bastidas V, Weissman M, Fifer WP, et al. Associations between brain structure and connectivity in infants and exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172(6):525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf DR. EEG sleep spindle ontogenesis. Neuropadiatrie 1970;1(4):428–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milh M, Kaminska A, Huon C, Lapillonne A, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Rapid cortical oscillations and early motor activity in premature human neonate. Cereb Cortex 2007;17(7):1582–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Colonnese MT. Thalamic inhibitory circuits and network activity development. Brain Res 2019;1706:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MM, Grieve PG, Izraelit A, Fifer WP, Isler JR, Darnall RA, et al. Developmental profiles of infant EEG: overlap with transient cortical circuits. Clin Neurophysiol 2012;123(8):1502–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MM, Grieve PG, Stark RI, Isler JR, Hofer MA, Yang J, et al. Family Nurture Intervention in preterm infants alters frontal cortical functional connectivity assessed by EEG coherence. Acta Paediatr 2015;104(7):670–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner J, Cha J, Roy AK, Peterson BS, Bansal R, Gustafsson HC, et al. Alterations in amygdala-prefrontal circuits in infants exposed to prenatal maternal depression. Transl Psych 2016;6(11) e935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Anh TT, Li Y, Chen H, Rifkin-Graboi A, Broekman BF, et al. Prenatal maternal depression alters amygdala functional connectivity in 6-month-old infants. Transl Psychiat 2015;5 e508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991;20(2):149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit D, Perel JM, Wisniewski SR, Helsel JC, Luther JF, Wisner KL. Mother-infant antidepressant concentrations, maternal depression, and perinatal events. J Clin Psychiat 2011;72(7):994–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolonen M, Palva JM, Andersson S, Vanhatalo S. Development of the spontaneous activity transients and ongoing cortical activity in human preterm babies. Neurosci 2007;145(3):997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videman M, Tokariev A, Saikkonen H, Stjerna S, Heiskala H, Mantere O, et al. Newborn brain function is affected by fetal exposure to maternal serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Cereb Cortex 2017;27(6):3208–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead K, Pressler R, Fabrizi L. Characteristics and clinical significance of delta brushes in the EEG of premature infants. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2017;2:12–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Chang M, Wei S, Jiang X, Zhou Y, Cui L, et al. Decreased functional connectivity in insular subregions in depressive episodes of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Front Neurosci 2018;12:842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]