Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) risk, number of positive biopsy cores, age, and early confirmatory test results on pathological upgrading at radical prostatectomy (RP), in order to better understand whether early confirmatory testing and better risk stratification are necessary for all men with Grade Group (GG) 1 cancers who are considering active surveillance (AS).

Patients and Methods

We identified men in Michigan initially diagnosed with GG1 prostate cancer, from January 2012 to November 2017, who had a RP within 1 year of diagnosis. Our endpoints were: (i) ≥GG2 cancer at RP and (ii) adverse pathology (≥GG3 and/or ≥pT3a). We compared upgrading according to NCCN risk, number of positive biopsy cores, and age. Last, we examined if confirmatory test results were associated with upgrading or adverse pathology at RP.

Results

Amongst 1966 patients with GG1 cancer at diagnosis, the rates of upgrading to ≥GG2 and adverse pathology were 40% and 59% (P< 0.001), and 10% and 17% (P= 0.003) for patients with very-low-and low-risk cancers, respectively. Upgrading by volume ranged from 49% to 67% for ≥GG2, and 16% to 23% for adverse pathology. Generally, more patients aged ≥70 vs <70 years had adverse pathology. Unreassuring confirmatory test results had a higher likelihood of adverse pathology than reassuring tests (35% vs 18%, P= 0.017).

Conclusions

Upgrading and adverse pathology are common amongst patients initially diagnosed with GG1 prostate cancer. Early use of confirmatory testing may facilitate the identification of patients with more aggressive disease ensuring improved risk classification and safer selection of patients for AS.

Keywords: #PCSM, #UroOnc, active surveillance, confirmatory testing, prostate cancer

Introduction

A major limitation to the adoption of active surveillance (AS) is adequate risk stratification; some men diagnosed with favourable-risk prostate cancer have higher grade or stage cancers than appreciated on initial biopsy. This concern is underscored by the fact that nearly 40% of patients with Grade Group (GG) 1 cancers at diagnosis have higher grade pathology at radical prostatectomy (RP) [1]. The disease risk in these patients is misclassified at the time of diagnosis due to prostate biopsy under-sampling. Concerns about misclassification contribute to both provider and patient hesitation with selecting AS for primary management of patients with GG1 and/or low-volume GG2 disease [2,3].

Recognising that risk of misclassification at diagnosis may drive variation in practice patterns and limit the optimal use of AS, the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MUSIC) began a quality improvement initiative in 2016 promoting the use of early confirmatory testing (repeat biopsy, MRI, and/or genomic classifiers) within 6 months of the original diagnostic biopsy [3]. This recommendation is predicated on the notion that these confirmatory tests, admittedly with varied and evolving performance characteristics, facilitate identification of patients with higher-risk or grade cancers early after diagnosis, allowing for a more informed shared decision-making.

While the MUSIC currently recommends early confirmatory testing for all men with favourable-risk disease who are considering AS, these tests carry additional expense and morbidity, and there may be a sub-group of patients for whom these examinations may not be routinely indicated. For instance, men with 1 or 2 cores of GG1 cancer, or those with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defined very-low-risk disease, have a low probability of cancer progression while on AS [4]; as such, it may be relatively inefficient from a quality and cost perspective to perform routine early confirmatory tests in these patients considering AS. It is also possible that patient age could influence the utility of confirmatory testing, as the benefits of both early detection and aggressive local therapy are reported to be less apparent amongst men aged ≥70 years [5,6].

In this context, we examined the frequency of upgrading to any ≥GG2 cancer and adverse pathological features at RP according to three specific criteria: (i) NCCN risk strata, (ii) number of positive biopsy cores (i.e., presumed cancer volume), and (iii) age ≥70 vs <70 years. In addition, we evaluated whether the results of confirmatory tests in this group of patients are associated with upgrading and/or upstaging with RP.

Patients and methods

The MUSIC

The MUSIC is a physician-led quality improvement collaborative that aims to improve the quality and decrease costs of urological care. The collaborative currently includes ~90% of urologists in Michigan and spans 44 practices. Each participating practice has a trained data abstractor who enters demographic and clinical data into a web-based registry for every patient undergoing a prostate biopsy and/or those with newly diagnosed prostate cancer.

Study population

We identified all men in the MUSIC registry who were originally diagnosed with GG1 prostate cancer from January 2012 to November 2017, and who underwent RP within 1 year of diagnosis. The time interval for RP was chosen because tumour upgrading on RP specimens within this time period more likely represents misclassification at the time of initial prostate biopsy, rather than tumour progression, which likely occurs at longer time intervals. Patients with neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgery were excluded (10 patients). In addition, because saturation biopsy is not the standard of care for the initial evaluation of an elevated PSA level, we excluded patients who were diagnosed with a prostate biopsy involving ≥24 cores (51 patients).

We used data routinely available in the MUSIC registry to determine age, Gleason score, PSA, prostate volume, treatment, and surgical pathology data. In addition, since 2016, data on the utilisation and results of early confirmatory tests for patients considering AS have been routinely entered into the registry.

Exposure variables

We classified all men with a newly diagnosed GG1 prostate cancer according to whether or not they met criteria for NCCN very-low- or low-risk disease and the number of positive cores from the initial diagnostic biopsy [7]. Patients with missing PSA density (based on missing prostate volume or PSA data) but meeting all other NCCN criteria for low-risk disease were included in the low-risk cohort.

We also examined the relationship between early confirmatory test results and pathological outcomes at the time of RP. Confirmatory tests recorded in the MUSIC registry include repeat prostate biopsy, prostate MRI, and/or molecular classifier testing performed within 6 months of the original diagnostic prostate biopsy [3]. Molecular classifier tests include: the Prolaris cell cycle progression score (Myriad Genetics, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), the Decipher® genomic classifier (GenomeDx Biosciences, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), and the Oncotype Dx genomic prostate score (Genomic Health Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA). Reassuring confirmatory test results were classified by the following criteria: prostate biopsy remaining GG1; MRI, maximum Prostate Imaging - Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS), version 2, score of 1–3; Prolaris <3% probability of prostate cancer mortality; Oncotype Dx >80% freedom from adverse pathology; Decipher <0.45. Although there are no absolute criteria to define reassuring vs unreassuring results for molecular classifiers, the thresholds employed in this analysis are outlined in the reports to physicians and patients and have been used in previous publications [8–11].

Outcome

Our primary outcome was the rate of pathological upgrading, designated by either: (i) the presence of ≥GG2 cancer in the RP specimen; or (ii) the presence of adverse pathology in the RP specimen. Consistent with other reports, we defined adverse pathology as ≥GG3 cancer, extraprostatic extension (pT3a), seminal vesicle invasion (pT3b), or lymph node involvement (pN1) [12–14].

Statistical analysis

We first generated descriptive statistics assessing the proportion of patients meeting NCCN criteria for low- or very-low-risk cancers and the number of positive biopsy cores. We then evaluated the rates of upgrading to ≥GG2 cancer and rates of adverse pathology across the entire collaborative. Next, we compared the frequency of pathological upgrading and adverse pathology according to the number of biopsy cores positive for GG1 disease and by NCCN risk strata. We then stratified these analyses by age, comparing the same outcomes for patients aged <70 vs ≥70 years. Finally, we evaluated the association between confirmatory test result (i.e., reassuring or unreassuring) and the frequency of upgrading and adverse pathology at RP.

We used chi-squared tests to evaluate statistical significance of the associations of interest. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) at the 5% significance level. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed two sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated our analyses after excluding patients with missing data for PSA density. Second, because there are varying definitions of adverse pathology with RP, we also repeated our analyses using a more conservative definition of adverse pathology: ≥GG3 cancer and/or ≥pT3b, terminology which has also been previously established [2].

Results

We identified 1966 patients diagnosed with only GG1 prostate cancer on initial prostate biopsy who underwent RP within 1 year of diagnosis. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of our cohort. In all, 48% of patients had 1–2 positive cores, 28% had 3–4 cores, and 24% had ≥5 cores positive for GG1 cancer. Overall, 84% of patients initially diagnosed with GG1 disease were classified as having very-low-(295, 15%) or low-risk (1347, 68.5%) disease according to NCCN criteria.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1966 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 60.9 (55.8–65.8) |

| Categorical age, years (in deciles), n (%) | |

| <40 | 4 (0.2) |

| 40–49 | 134 (6.8) |

| 50–59 | 741 (37.7) |

| 60–69 | 920 (46.8) |

| 70–79 | 166 (8.4) |

| ≥80 | 1 (0.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 1538 (86.7) |

| Black | 197 (11.1) |

| Other | 38 (2.1) |

| PSA level, ng/mL, median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.0–6.9) |

| Number of positive cores at original biopsy, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| Categorical number of cores positive, n (%) | |

| 1–2 | 939 (47.8) |

| 3–4 | 547 (27.8) |

| ≥5 | 480 (24.4) |

| NCCN risk strata, n (%) | |

| NCCN very-low risk | 295 (15.0) |

| NCCN low risk | 1 347 (68.5) |

| Not NCCN low or very-low risk | 324 (16.5) |

| Insurance type, n (%) | |

| Private | 1358 (71.5) |

| Public | 532 (28.0) |

| None | 9 (0.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28.2 (25.7–31.1) |

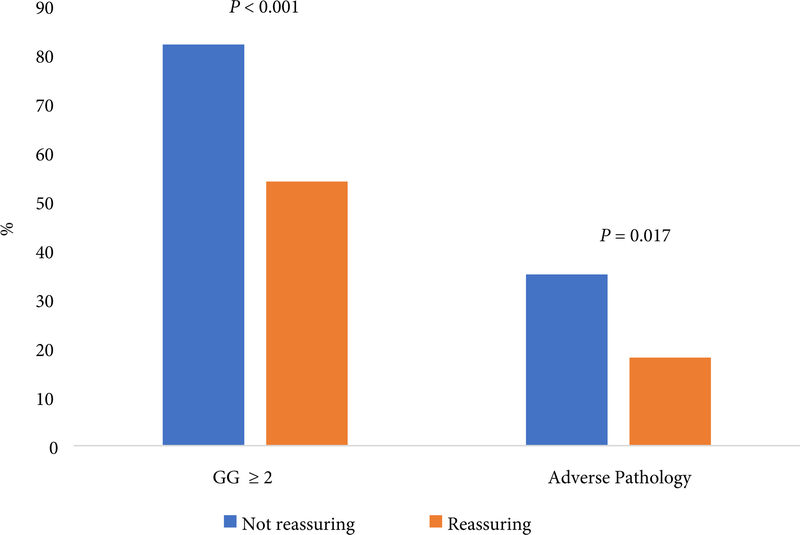

Pathological upgrading was both common and highly variable according to the number of positive cores on diagnostic biopsy. The proportion of patients upgraded to any ≥GG2 disease was 40% and 59% (P< 0.001) for very-low- and low-risk patients, respectively; and 10% and 17% of patients in these groups had adverse pathology (P= 0.003). The same pattern held true when evaluating by volume, where the rates of upgrading to ≥GG2 disease ranged from 49% (1–2 positive cores, n= 460) to 67% (≥5 positive cores, n= 322) (P< 0.001), whilst the frequency of adverse surgical pathology ranged from 16% (1–2 cores) to 23% (≥5 cores) (P= 0.005; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of pathological upgrading or adverse pathology by (A) NCCN defined very-low- and low-risk disease and (B) Number of biopsy cores positive for GG1 cancer.

*Adverse pathology: ≥ GG3, ≥ pT3a

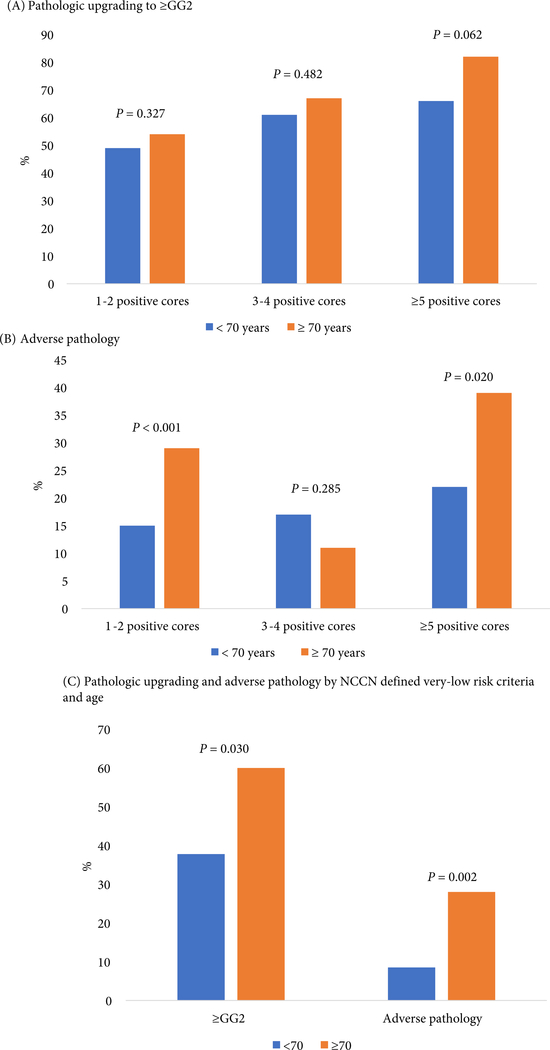

A greater proportion of patients aged ≥70 years had adverse pathology when initially diagnosed with 1–2 cores (29% vs 15%, P< 0.001) and ≥5 cores (39% vs 22%, P= 0.020) of GG1 cancer compared with those aged <70 years (Fig. 3). Likewise, men aged ≥70 years with very-low-risk disease had higher rates of upgrading (60% vs 38%, P= 0.030) and adverse pathology (28% vs 9%, P= 0.002) than those aged <70 years (Fig. 2).

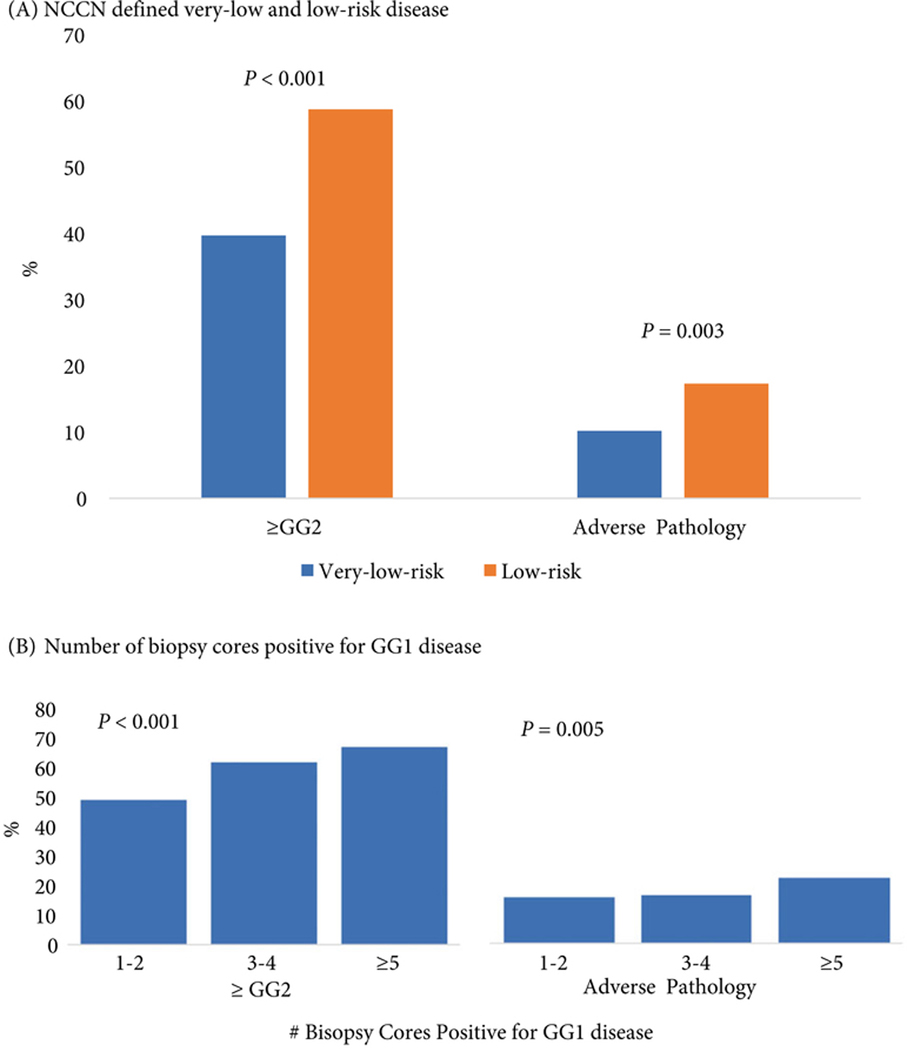

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with upgrading or adverse features at the time of RP, according to confirmatory test result

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients with (A) Pathological upgrading or (B) Adverse pathology according to the number of biopsy cores positive for GG1 cancer and age, and (C) Pathological upgrading and adverse pathology by NCCN defined very-low-risk criteria and age.

Since 2016, 22% of patients underwent confirmatory testing (n= 171; 9% overall). The distribution of confirmatory testing included repeat biopsy in 31.0% (n= 53), prostate MRI in 34.5% (n= 59), and genomic classifiers in 34.5% (n= 59). Amongst this group, 51% (n= 87) had a confirmatory test result classified as reassuring.

The frequency of upgrading and adverse pathological features on RP specimens was significantly higher amongst patients with unreassuring confirmatory test results at 82% vs 54% upgraded (P< 0.001) and 35% vs 18% (P= 0.017) had adverse pathology for unreassuring and reassuring results, respectively (Fig. 3).

There were no substantive changes to our findings when we excluded patients with missing data on PSA density (Table S1) or with the more limited definition of adverse pathology (Table S2).

Discussion

In a cohort of patients with GG1 prostate cancer from diverse academic and community practices, pathological upgrading was common even amongst patients with the lowest risk types of prostate cancer. For instance, nearly 40% of patients with NCCN very-low-risk disease were upgraded to ≥GG2 on final pathology. Furthermore, many of these patients had adverse surgical pathology, including 10% of men with verylow-risk disease and 16% of men with 1–2 cores positive for GG1 cancer. Moreover, 28% of men aged ≥70 years with very-low-risk disease had adverse pathological features at the time of RP. Finally, both pathological upgrading (82% vs 54%, P< 0.001) and adverse pathology (35% vs 18%, P= 0.017) were significantly more common amongst patients with unreassuring vs reassuring confirmatory test results.

Our present findings around the rates of upgrading and adverse pathology even with low-volume or low-risk disease are consistent with previously published literature. An evaluation of upgrading in patients undergoing RP determined that nearly 40% of patients originally diagnosed with Gleason 5–6 cancer were upgraded on RP pathology [1]. Furthermore, an analysis of a national database from Sweden, containing clinical and pathological data for 97% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the country, found that 50% of patients originally diagnosed with Gleason 6 cancer, had adverse pathology (≥Gleason 7 or ≥pT3) at RP, including more than one-third of the men meeting the most stringent AS selection criteria [15]. Similarly, a recent assessment of adverse pathological findings (defined by Gleason score of ≥4 + 3, pT3b, or pN1) at the time of immediate RP identified adverse pathology rates of 4.7%, 5.8% and 24.7% for patients diagnosed with very-low-, low-, or low-volume intermediate-risk disease, respectively [2]. Although our estimates are higher than those reported in the latter analysis, we included extraprostatic extension in our definition of adverse pathology and our patients (and corresponding prostate biopsies and pathology reads) reflect practices occurring across the state of Michigan rather than a single high-volume institution with central pathology review.

In addition, our present finding that pathological upgrading was common regardless of tumour volume is consistent with a recent publication examining the association between disease reclassification by genomic classifiers and biopsy tumour volume. That analysis of men with very-low- and low-risk prostate cancer at diagnosis determined that genomic disease reclassification was independent of biopsy tumour volume [16]. Last, our determination that the frequency of upgrading and adverse pathological features on RP specimens was significantly higher for patients with unreassuring compared to reassuring confirmatory test results highlights that confirmatory test results are providing the patient and physician with valuable and reliable information, and that patients and/or physicians are acting on the confirmatory test results. Taken together, these data indicate that tumour volume of GG1 cancers is, on its own, an incomplete predictor of adverse pathology.

Our present study has several limitations. First, we only include men with GG1 pathology on initial diagnostic biopsy who underwent a RP, and thus, our sample could over- or under-estimate pathological upgrading. However, pathology at RP is currently the best way to evaluate pathology of the entire prostate gland. Second, we use pathology at RP as a surrogate endpoint for higher risk with AS. Despite this concern, our analyses aim to understand the accuracy of initial risk stratification, given its importance in treatment decision-making. Third, because the MUSIC has only been collecting data on confirmatory MRIs and molecular classifier tests since 2016, our present sample size for the use of confirmatory testing (and therefore the results of the confirmatory tests) is small relative to the entire GG1 prostate cancer cohort. Even so, we still identified statistically significant differences in the rates of upgrading and adverse pathology by confirmatory test result. Fourth, significant variability exists between the accuracy in identification and grading of PI-RADS lesions, the ability to target and capture the MRI-identified lesion at the time of the MRI-TRUS fusion biopsy, and pathologists’ assignments of Gleason score, which could all impact both the reassuring test result and the rate of upgrading. However, these differences reflect realworld patterns across academic and community practices. Fifth, the share of patients upgraded to adverse pathology at the time of RP may be overestimated as we do not routinely collect data on extraprostatic extension or seminal vesicle invasion on prostate biopsy specimens, nor do we extract data on seminal vesicle invasion on MRIs. However, although MRI results can suggest adverse pathology, they are not 100% sensitive and/or specific for adverse pathology, and the RP specimen remains the ‘gold standard’ for staging data. We also cannot comment on downgrading as our present cohort only consists of patients who were diagnosed with GG1 disease. Finally, there is no universally accepted threshold for defining various confirmatory test results as reassuring or unreassuring; the results vary depending on the clinical scenario. Nonetheless, the definitions used in the present study reflect the criteria used for reporting in prior literature [8–11].

These limitations notwithstanding, our present findings have important implications for clinicians, patients, and payers. There is substantial evidence that our current risk stratification criteria for patients considering AS are unacceptably coarse; indeed, heterogeneity of risk within the classic D’Amico or NCCN criteria is large. Historically, when the vast majority of patients were treated for any diagnosis of prostate cancer, this heterogeneity was arguably less relevant from a pragmatic clinical perspective. However, the limits of these criteria are increasingly evident now that AS has been widely accepted as an appropriate management strategy for patients with favourable-risk prostate cancer. This heterogeneity, and therefore challenges with risk stratification, lead to uncertainty with AS and wide variation in practice patterns [17,18]. In the absence of better prognostic information from historically used diagnostic parameters, we now have several routinely available confirmatory tests including repeat biopsy, prostate MRI, and/or genomic classifiers, to decrease misclassification, improve risk stratification, confirm a patient’s appropriateness for AS, and enhance counselling.

Our present analyses therefore highlight the potential importance of early confirmatory testing with either repeat biopsy, prostate MRI, or genomic classifiers to aid in the appropriate selection of patients enrolling in AS. Our present findings suggest that early confirmatory testing for patients considering AS has the potential to meaningfully reduce misclassification due to sampling error and therefore better risk stratify and guide patient decision-making.

Taken together, our present findings suggest that initial NCCN risk strata, biopsy tumour volume, and age at diagnosis do not immediately identify patients in whom confirmatory testing can be omitted. Moving forward, the usefulness of confirmatory testing for predicting pathological upgrading, biochemical recurrence, metastatic disease and death should be evaluated on a broader scale; this should include an analysis of which confirmatory test is most precise for predicting these important endpoints. In addition, further refining the criteria for confirmatory testing will be important; these additional criteria should include patient co-morbidity and life expectancy. Finally, cost-effectiveness analyses will also play a role in defining the optimal population-level approach to confirmatory testing amongst men considering AS for newly diagnosed, favourable-risk prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (5-T32-CA-180984–03 to DRK) and by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships Program. The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of BCBSM or any of its employees.

David C. Miller: Contract support from the BCBSM for the Michigan Value Collaborative (MVC) and the MUSIC.

Abbreviations:

- AS

active surveillance

- GG

Grade Group

- MUSIC

Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- RP

radical prostatectomy

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Conflict of Interests

References

- 1.Epstein JI, Feng Z, Trock BJ, Pierorazio PM. Upgrading and downgrading of prostate cancer from biopsy to radical prostatectomy: incidence and predictive factors using the modified Gleason grading system and factoring in tertiary grades. Eur Urol 2012; 61: 1019–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel HD, Tosoian JJ, Carter HB, Epstein JI. Adverse pathologic findings for men electing immediate radical prostatectomy: defining a favorable intermediate-risk group. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 89–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auffenberg GB, Lane BR, Linsell S et al. A roadmap for improving the management of favorable risk prostate cancer. J Urol 2017; 198: 1220–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tosoian JJ, Mamawala M, Epstein JI et al. Intermediate and longer-term outcomes from a prospective active-surveillance program for favorablerisk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3379–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 132–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1977–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Version 3, 2016. Available at: https://www.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/urological/english/prostate.pdf Accessed January 2018

- 8.Latifoltojar A, Dikaios N, Ridout A et al. Evolution of multi-parametric MRI quantitative parameters following transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2015; 18: 343–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prolaris. Understanding the Prolaris Score. Available at: https://prolaris.com/prolaris-for-physicians/understanding-the-prolaris-score/ Accessed December 2017

- 10.Decipher. Providing Treatment Information for Prostate Cancer Patients. Available at: http://deciphertest.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/PhysBrochDDR2017.9.pdf Accessed December 2017

- 11.OncotypeDx. Healthcare Professionals: Oncotype Dx Genomic Prostate Score. Available at: http://www.oncotypeiq.com/en-US/prostate-cancer/healthcare-professionals/oncotype-dx-genomic-prostate-score/interpreting-theresults Accessed December 2017

- 12.Reese AC, Feng Z, Landis P, Trock BJ, Epstein JI, Carter HB. Predictors of adverse pathology in men undergoing radical prostatectomy following initial active surveillance. Urology 2015; 86: 991–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swanson GP, Basler JW. Prognostic factors for failure after prostatectomy. J Cancer 2011; 2: 1–19 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozminski MA, Tomlins S, Cole A et al. Standardizing the definition of adverse pathology for lower risk men undergoing radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol 2016; 34: 415 e1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vellekoop A, Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Stattin P. Population based study of predictors of adverse pathology among candidates for active surveillance with Gleason 6 prostate cancer. J Urol 2014; 191: 350–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyame YA, Grimberg DC, Greene DJ et al. Genomic scores are independent of disease volume in men with favorable risk prostate cancer: implications for choosing men for active surveillance. J Urol 2018; 199: 438–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spratt DE, Zhang J, Santiago-Jimenez M et al. Development and validation of a novel integrated clinical-genomic risk group classification for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 581–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooperberg MR, Pasta DJ, Elkin EP et al. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2005; 173: 1938–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.