Abstract

Heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs) are mutagens and potential human carcinogens. Our group and others have demonstrated that HAAs may also produce selective dopaminergic neurotoxicity, potentially relevant to Parkinson’s disease (PD). The goal of this study was to elucidate mechanisms of HAA-induced neurotoxicity through examining a translational biochemical weakness of common PD models. Neuromelanin is a pigmented byproduct of dopamine metabolism that has been debated as being both neurotoxic and neuroprotective in PD. Importantly, neuromelanin is known to bind and potentially release dopaminergic neurotoxicants, including HAAs (eg, β-carbolines such as harmane). Binding of other HAA subclasses (ie, aminoimidazoaazarenes) to neuromelanin has not been investigated, nor has a specific role for neuromelanin in mediating HAA-induced neurotoxicity been examined. Thus, we investigated the role of neuromelanin in modulating HAA-induced neurotoxicity. We characterized melanin from Sepia officinalis and synthetic dopamine melanin, proposed neuromelanin analogs with similar biophysical properties. Using a cell-free assay, we demonstrated strong binding of harmane and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) to neuromelanin analogs. To increase cellular neuromelanin, we transfected SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with tyrosinase. Relative to controls, tyrosinase-expressing cells exhibited increased neuromelanin levels, cellular HAA uptake, cell toxicity, and oxidative damage. Given that typical cellular and rodent PD models form far lower neuromelanin levels than humans, there is a critical translational weakness in assessing HAA-neurotoxicity. The primary impacts of these results are identification of a potential mechanism by which HAAs accumulate in catecholaminergic neurons and support for the need to conduct neurotoxicity studies in systems forming neuromelanin.

Keywords: neuromelanin, PhIP, harmane, Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects > 1 out of 100 individuals over the age of 60 years in the United States (Davie, 2008). The loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and resultant striatal dopamine depletion produce most motor symptoms (Halliday et al., 2011). Although environmental exposures have received much attention, the etiology of PD is largely unknown (Cannon and Greenamyre, 2011).

Diet is important to neurological function and long-term brain health (Agim and Cannon, 2015; Chen et al., 2002). Heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs) are primarily produced during high-temperature meat cooking (Skog et al., 1998). Heterocyclic aromatic amines have been widely investigated in cancer research as mutagens, but may also be neurotoxic (Agim and Cannon, 2015; Skog et al., 1998; Turesky, 2007). Direct brain HAA [3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole (Trp-P-1), 3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole (Trp-P-2), or 2-methyl-norharman] infusion depletes striatal dopamine (Ichinose et al., 1988; Kojima et al., 1990; Neafsey et al., 1989). Furthermore, β-carbolines (HAA subclass) are elevated in blood and cerebrospinal fluids of PD patients (Kuhn et al., 1996; Louis et al., 2014). Indeed, HAA neurotoxicity research has primarily focused on the β-carboline subclass due to structural similarity to known dopaminergic neurotoxicants (Albores et al., 1990; Drucker et al., 1990). However, we recently showed that the most abundant dietary HAA, 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP, an aminoimidazoaazarene), is selectively toxic to dopaminergic neurons in a mixed primary culture system (Griggs et al., 2014). In addition, HAAs across 3 subclasses (aminoimidazoaazarenes, α-carbolines, and β-carbolines) are toxic to dopaminergic neurons with varying potency (Cruz-Hernandez et al., 2018). Furthermore, a systemic in vivo study in rats showed that PhIP selectively affects dopaminergic neurotransmission and produces heightened oxidative damage specifically in nigral dopaminergic neurons (Agim and Cannon, 2018). Although the results from this in vivo study further underscore potential PD relevance, the requirement for high doses (100–200 mg/kg) relative to actual exposures and a lack of an overt lesion to the nigrostriatal dopamine system raise questions about translational differences between PD models and human patients (Agim and Cannon, 2015, 2018). Thus, the goal of this study was to elucidate mechanisms of HAA-induced neurotoxicity through examining a translational biochemical weakness of common PD models.

Neuromelanin is a heterogeneous, polymeric dark pigment of 5,6-dihydroxyindole monomers that is produced in catecholaminergic neurons predominantly located in substantia nigra and locus coeruleus regions of the human brain; whereas peripheral melanin, produced by melanocytes is present in hair, skin, iris, and choroid of eye and inner ear, is characterized by a more homogenous shape (Charkoudian and Franz, 2006; Fedorow et al., 2005; Prota, 2000). In dopaminergic neurons, excess dopamine oxidization products are key precursors in neuromelanin generation (Matsunaga et al., 2002; Zucca et al., 2017). The role of neuromelanin in PD pathogenesis remains controversial. Neuroprotective properties such as an ability to bind metals, especially iron, forming stable complexes, and blocking neurotoxic effects have been identified (Korytowski et al., 1995; Zecca et al., 2001, 2008b). In contrast, neurons with higher neuromelanin content are more susceptible to cell death (Gibb, 1992; Hasegawa, 2010; Hirsch et al., 1988; Mann and Yates, 1983). Neuromelanin can promote neurotoxicity by impairing the ubiquitin-proteasomal system, causing mitochondrial oxidative stress, and inducing neuroinflammation (Shamoto-Nagai et al., 2004, 2006; Zhang et al., 2011). It remains unclear if neuromelanin in these neurons directly mediates sensitivity, or if such neurons accumulate more oxidative stress, and as a secondary downstream effect, form neuromelanin as an initial protective response.

Of significant importance to environmentally induced PD, studies show that several neurotoxic compounds, including β‐N‐methylamino‐l‐alanine, chloroquine, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, paraquat, and harmane, bind to neuromelanin, with potential for later cellular release (D'Amato et al., 1987; Karlsson et al., 2009; Langston et al., 1999; Lindquist et al., 1988; Ostergren et al., 2007; Sokolowski et al., 1990). Cellular and rodent models form far lower neuromelanin (virtually undetectable) versus humans, and species with neuromelanin accumulate far higher toxin levels in dopaminergic neurons (Fedorow et al., 2005). Furthermore, dopamine oxidation mediates critical interactions between pivotal pathogenic pathways in human PD model systems; such interactions in rodents are limited because of differences in dopamine metabolism that are underscored by a lack of neuromelanin (Burbulla et al., 2017). Thus, it is clear that widely used rodent PD models have a major translational deficiency in the relative lack of neuromelanin in assessing environmental PD risk factors. Furthermore, given that HAAs such as harmane bind to neuromelanin, the specific role of neuromelanin in mediating HAA-induced neurotoxicity warrants investigation.

In this study, we aimed to test the hypothesis that neuromelanin modulates neuronal HAA levels and neurotoxicity. It is expected that the results will both further the development of more translational PD risk assessments and increase understanding of mechanisms of HAA-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rationale for utilization of neuromelanin analogs

The most commonly used preclinical models to study PD-associated dopaminergic neurotoxicity (rodents and in vitro cultures) form relatively low amounts of neuromelanin (Double et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2011; Shamoto-Nagai et al., 2006). Neuromelanin itself is difficult to isolate and purify. Thus, different forms of melanin have been proposed to model this important biomolecule. Neuromelanin is believed to contain eumelanin and pheomelanin-like compounds, which form the spherical particles of neuromelanin (Ito, 2006; Wakamatsu et al., 2003). Two specific studies have determined the particle size of neuromelanin to be approximately 300 nm (Bush et al., 2006; Zecca et al., 2008a). Melanin obtained from common cuttlefish Sepia officinalis (Sepia melanin) is one of the most common model forms of neuromelanin (Schroeder et al., 2015; Schroeder and Gerber, 2014). Structurally, the Sepia melanin particles are spherical in shape (approximately 150 nm diameter) (Liu and Simon, 2005). In contrast, synthetic neuromelanin prepared from dopamine [referred to here as dopamine melanin (DAM)] has been used to study neuromelanin in cell-free systems (Bayles et al., 2016; Dubochet et al., 1971; Oberlander et al., 2011; Ostergren et al., 2004; Wu and Hong, 2016).

Dopamine melanin (DAM) synthesis

DAM was synthesized from dopamine using protocols described by Haining et al. (2016) and Oberlander et al. (2011). In brief, we added 0.33 mM l-cysteine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, CAT No. 30120), 0.1 mM cupric sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. 451657), and 4 mM sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. S8045) to 2 mM dopamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. H8502) dissolved in PBS. The dopamine hydrochloride solution was first deoxidized by passing nitrogen gas through the solution with vigorous stirring for 15–30 min. The solution was kept at 37°C for 5–7 days to achieve auto-oxidation, and the resulting dark-brown colored solution was centrifuged at 10 000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed with 0.33 mM l-cysteine hydrochloride solution 5 times and lyophilized to generate homogenous granules. The lyophilized DAM was resuspended in PBS (pH 7.4) and stored at −20°C for future use. This process yielded approximately 40 mg of DAM.

Melanin characterization through dark-field microscopy

Using dark-field microscopy, we imaged 1 mg/ml suspension of 2 melanins, melanin from S. officinalis (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. M2649) and synthetic DAM. The melanin suspensions were observed by hyperspectral enhanced dark-field microscopy (Cytoviva, Auburn, Alabama).

Melanin characterization through nanoparticle tracking

To further evaluate the physical characteristics of these particles relative to the known biophysical properties of neuromelanin, particles were subjected to nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight LM10. This method uses a laser beam that passes through the sample suspension. The particles in suspension scatter light, which allows the analysis of particle counts and size (Adamson et al., 2018; Harischandra et al., 2019). The NanoSight LM10 NTA software was used to determine the particle size distribution and particle counts from each sample. The data generated from 3 independent observations were then combined the values were reported as mean ± SEM.

Melanin binding assay

2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and harmane were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Metabolites of PhIP (4′-hydroxy PhIP, N-hydroxy PhIP and nitro PhIP) were synthesized and obtained from Dr R. Turesky at the University of Minnesota. The 100 mM PhIP stocks for aforementioned HAAs were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and further dilutions were made in PBS (pH 7.4). First, we determined the λmax for harmane and PhIP and for active metabolites of PhIP (in phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4), by obtaining an absorbance spectrum from 270 to 470 nm with 1 nm steps. Pilot analyses showed λmax of 290, 320, 322, 322, and 364 nm for harmane, PhIP, 4′-OH PhIP, N-OH-PhIP, and NO2-PhIP, respectively. We used caffeine (λmax = 286 nm), a heterocyclic, nitrogen-containing compound, as a negative control. Indeed, caffeine has been reported to have a low-affinity for synthetic neuromelanin (Haining et al., 2016). Next, we examined the time-dependent binding of these analytes to neuromelanin analogs using an established melanin binding assay reported by Haining et al. (2016). Here, we incubated equal volumes of harmane and PhIP (50 µM–30 mM) and Sepia melanin or DAM (1 mg/ml) for 1 h with shaking (300 rpm) at 22°C, followed by centrifugation at 10 000 × g for 10 min. The supernatants containing unbound analytes were collected and analyzed spectrophotometrically at the respective λmax for each analyte. The amount of each unbound analyte was then calculated from standard curves, and the concentration of melanin-bound analyte was calculated by subtracting the concentration of unbound analyte from the total concentration. Saturation binding curves and scatchard plots were constructed.

Cell culture

Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells are a widely used model for PD-related dopaminergic neurotoxicity studies (Griggs et al., 2014; Sanyal et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2018). The cells were obtained from ATCC and grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. R1382), supplemented with 15% NuSerum (Corning, Inc, Corning, New York, CAT No. 355500), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, CAT No. 15140-122), 1% Glutamine (Invitrogen, CAT No. 3505-061), 0.01% w/v sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. P5280), 0.37% w/v sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. S5761), and 1% 1 M HEPES (Corning, Inc, CAT No. 61-034RM). Stable galactose-supplemented cell subclones were created to generate cells with high reliance on oxidative phosphorylation (vs typical glucose-supplemented cultures) that are more relevant to the production of in vivo neurons (de Rus Jacquet et al., 2017). Here, we supplemented the neuroblastoma cells with 0.18% d-galactose (Teknova, Hollister, California, CAT No. G050).

Ectopic tyrosinase expression as a strategy to increase neuromelanin formation

1435 pSG5L Flag HA was a gift from William Sellers (Addgene plasmid # 10791; http://n2t.net/addgene:10791; RRID:Addgene_10791). p3xFLAG-TYR was a gift from Ruth Halaban (Addgene plasmid # 32780; http://n2t.net/addgene:32780; RRID:Addgene_32780). In this study, we transfected galactose-conditioned SH-SY5Y cells (de Rus Jacquet et al., 2017) with empty vector (EV) or human tyrosinase (TYR) construct using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent following the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, CAT No. L3000008) (Halaban R, et al., 2002). Transfection efficiency of the tyrosinase-encoding plasmid was determined to be 3 ng/million cells, as the lower (< 3 ng/million cells) amount failed to generate detectable tyrosinase levels and higher amount (> 3 ng/million cells) induced cell death. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, we lysed the cells and determined tyrosinase expression levels via Western blotting for validation. Neuromelanin levels were analyzed using melanin assay and dark-field microscopy. The transfection efficiency was determined by Western blotting or ICC before each experiment.

Electron microscopy

The electron microscopic images were obtained at the Life Science Microscopy Facility (LSMF), Purdue University. For Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Sepia melanin and DAM particles were first coated with gold-palladium (Au: Pd; 6O: 40) layer using 208HR High Resolution Sputter Coater (Ted Pella, Inc, Redding, California) to increase the conductivity of the sample. The melanin particle agglomerates were imaged using an FEI NOVA nanoSEM field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, Oregon) using ET (Everhart-Thornley) detector or the high-resolution thorough-the lens (TLD) detector operating at 5 kV accelerating voltage, spot 3, approximately 5.0 mm working distance and 30 mm aperture. For further confirmation on melanin particles morphology, the particles were observed with Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). For TEM, Sepia melanin and DAM powders were suspended in distilled water, and a small drop of dilute dispersion of sonicated melanin samples were placed on TEM grids (discharged using Pelco easiGlow, Ted Pella, Inc). The TEM images were acquired using a Gatan US1000 2 K CCD camera on an FEI Tecnai G2 20 electron microscope equipped with a LaB6 source and operating at 200 kV.

For TEM images of SH-SY5Y cells, LSMF standard protocol was followed. In brief, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer 48 h after transfection with EV or TYR constructs. Then cells were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide buffer containing 0.8% potassium ferricyanide, and en bloc stained in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate. Cells were then dehydrated with a graded series of acetonitrile and embedded in EMbed-812 resin. Thin sections (80 nm) were cut on a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Camera, Wetzlar, Germany) and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The cell sections mounted on TEM grids and imaged using a Gatan Orius side mount CCD camera on an FEI/Philips CM-100 Transmission electron microscope operating at 40 kV.

Western blotting

We performed immunoblot analysis of tyrosinase according to previous published protocols (Lawana et al., 2017). Briefly, cell pellets were homogenized in modified RIPA buffer and incubated for 10 min on ice. After incubation, the samples were sonicated for 2.5 min with 30 s on/off setting at 40 kHz fixed pulse using Branson M1800 Ultrasonic Cleaner with Mechanical Timer and centrifuged at 20 000 × g for 45 min, and the protein concentration of the cell lysate was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, CAT No. 500-0006). SDS-polyacrylamide gels (10%) were loaded with 25 µg of protein in each well and run for 2 h at 110 V, after which proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (2 h, 120 V) at 4°C. After transfer, the membranes were incubated in LI-COR blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska) for 1 h at room temperature and treated with primary antibodies for 16 h, washed with phosphate buffer saline containing 0.01% Tween 20, treated with IR-secondary antibodies obtained from Rockland, washed again with PBS-Tween, and scanned using an Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-tyrosinase T3II (1:1000) (Invitrogen, CAT No. MA514177) and mouse anti-beta actin (1:5000) (Millipore, CAT No. MAB1501). Donkey anti-mouse secondary antibodies were used according to manufacturer’s instruction (IRDye, LI-COR).

Quantification of cellular neuromelanin

The amount of intracellular melanin was determined using previous protocol described by Zecca et al. (2002). In brief, 36–72 h after transfection, cells were collected and cell numbers were determined using trypan blue and a hemocytometer. Then the cells were centrifuged, lysed using RIPA buffer, diluted to 1 ml in 1N NaOH/10% DMSO and kept at 80°C for 2 h. Sepia melanin has been used to develop standard curve for melanin detection (Katritzky et al., 2002; Wakamatsu and Ito, 2002). Known concentrations (2–20 µg/ml) of Sepia melanin were prepared and kept at 80°C for 2 h for generation of the standard curve. After incubation, each tube was centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was then transferred to a 96-well plate, and the absorbance was measured at 470 nm. Neuromelanin content was determined using a standard curve, and values were calculated as pg/cell at each time point.

Quantification of PhIP uptake

Uptake of PhIP in cells with or without neuromelanin formation was quantified using radiolabeled PhIP (14C) (Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc, Ontario, Canada, CAT No. A617200, obtained as 50 mCi/mmol, quantity 25 µCi). SH-SY5Y cells transfected with EV or tyrosinase were treated with 100 nM 14C-PhIP for 24 h, and radioactivity was measured in cell lysates and media supernatants using a PerkinElmer Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (PerkinElmer Corp, Waltham, Massachusetts; Model Tri-Carb 2800TR) and reported as cpm. The counting efficiency was calculated for 1.1 × 105 DPM to be around 85.4%. 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine concentrations in treated cells and media were calculated from the standard curve that was obtained by measuring the cpm for known concentrations of 14C-PhIP and values were normalized by counting efficiency.

Cell viability

Cells with or without neuromelanin were exposed to various concentrations of HAAs (10 nM–300 µM) and their active metabolites for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed by the widely used MTT assay (Singh et al., 2018). Briefly, cells were incubated with 10 µl 12 mM of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] dye for 1 h at 37°C, and purple formazan particles formed in viable cells were dissolved in DMSO. A plate reader was used to record the absorbance at a wavelength of 490 nM. The values were converted to % of the control group value, and a dose-response curve was generated. Dose-response curve data was used to select an exposure (10 nM–300 µM) for time-course evaluation. To validate the MTT assay as a reliable marker for cell death analysis, we also determined dose-response curve for PhIP using Roche cell death assay kit, following manufacturer instructions. This assay assesses cell death through a different mechanism than the MTT assay, where a photometric enzyme-immunoassay is used to quantify cytoplasmic histone-associated-DNA-fragments (mono- and oligonucleosomes) after induced cell death (Singh et al., 2018).

Assessment of oxidative damage

In this study, we examined toxicant-mediated oxidative and nitrosative stress by measuring intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrotyrosine levels in SH-SY5Y cells with or without neuromelanin formation, treated with different concentrations of HAAs (100 nM–300 µM for 24 h), where the treatment concentration was based on MTT assay results. To measure intracellular ROS levels, cells were co-incubated with the fluorogenic dye CM-H2DCFDA (ThermoScientific, CAT No. C6827) (100 nM) and toxins, then washed twice with PBS. A SpectraMax multiwell plate reader was used to detect the fluorescence intensity at an excitation and emission wavelength of 488 and 525 nm, respectively. ROS levels were determined from the change in relative fluorescence units and converted to % of the control group value.

To further verify HAA-induced oxidative stress, we measured intracellular levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) using a previously described technique (Singh et al., 2018). We measured GSH levels in EV or tyrosinase-transfected SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 μM harmane or PhIP (1 × 106 cells per group) for 1–48 h. A subset of cells was pretreated with NAC (N-acetyl cysteine, 100 μM), a precursor of GSH, and then treated with 10 μM PhIP or harmane. The cells were lysed in freshly prepared buffer (50mM Tris, pH7.4, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.001% BHT), sonicated and centrifuged at 15 000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. To initiate the GSH reaction, the cell lysate was incubated with 1 mM monochlorobimane and 10U/ml glutathione S-transferase at room temperature. After 30 min, the change in fluorescence was measured using a Spectramax microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 480 and 645 nm, respectively. Fluorescence values were converted to GSH levels using a standard curve and presented as % of the control group value.

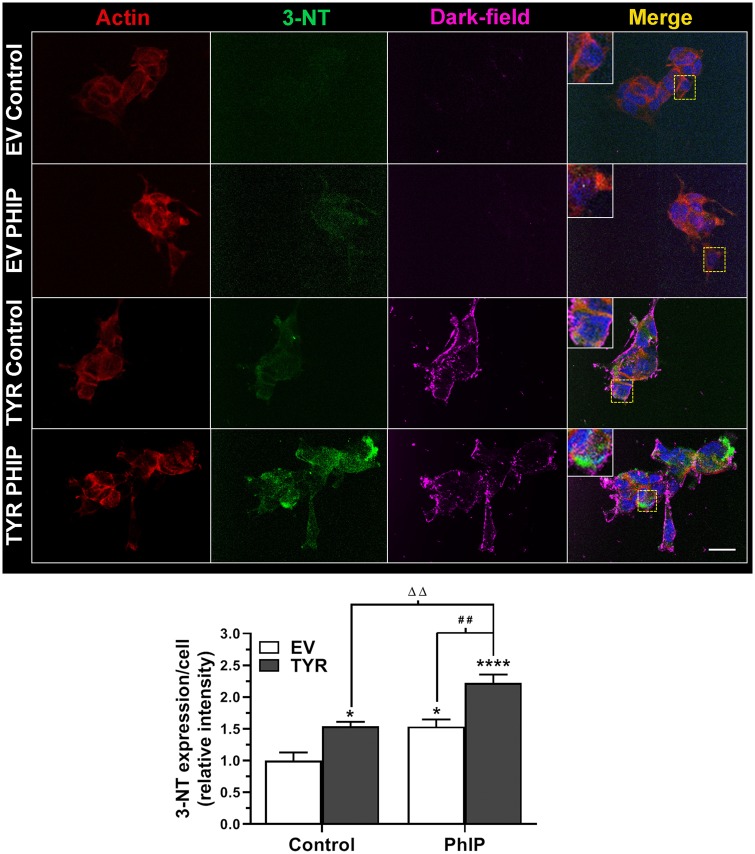

Finally, we quantified 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), a byproduct of tyrosine nitration and an established marker of nitrosative stress. Previously, we reported that exposure to HAAs increased intracellular 3-NT levels in primary mesencephalic neurons and in rat brain (Agim and Cannon, 2018; Cruz-Hernandez et al., 2018; Griggs et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015). Briefly, cells were plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (PDL) in a 24-well cell culture plate. Post-treatment, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min followed by blocking in 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.5% Triton X for 1 h. Then cells were treated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Following incubation, cells were washed with PBS, and then incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-beta actin (1:400; Millipore, CAT No. MAB1501) and rabbit anti-NT (1:250; Millipore, CAT No. 06-284). Secondary antibodies consisted of donkey anti-mouse Cy3 and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (1:500; Jackson IR Laboratories, West Grove, Pennsylvania, CAT No. 711-606-152). Hoechst 33342 (1:5000; Invitrogen, CAT No. 62249) was used as a nuclear stain. Cells were mounted on slides using the Fluoromount mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich, CAT No. F4680). To quantify nitrosative damage, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn around neuronal cells. The average 3-NT intensity of ROIs for an individual cell was quantified using ImageJ software and normalized to the mean of the control value in each experiment. The ROI from each cell served as a distinct data point with a rationale for analysis similar to that previously described by Agim and Cannon (2018).

Statistical analysis

Data from each endpoint were first subjected to a 2-way ANOVA test, followed by Sidak’s post hoc analysis for datasets showing statistically significant differences, using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). For all tests, p < .05 was deemed significant. Data were presented as mean±standard error of mean (SEM). GraphPad Prism 8 was also utilized to generate all curves and graphs.

RESULTS

DAM and Sepia Melanin Exhibit Similar Physical Properties to Neuromelanin

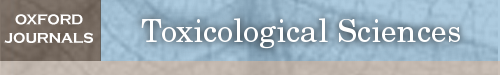

In principle, the dark-field microscope blocks the direct light and allows the visualization of diffracted light from the specimen, unlike in bright-field microscopy where the light is attenuated by the specimen (Herkenham et al., 1991; Kemali and Gioffre, 1985; Kim et al., 2005). This facilitates the observation of unstained samples that have the ability to scatter the source light, such as melanin. Numerous studies, both in vivo and in vitro, have demonstrated the use of dark-field microscopy for observing melanins, including neuromelanin (Adamson et al., 2018; Joseph et al., 2011; Oh et al., 2014). Dark-field microscopy shows neuromelanin-like molecules (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Biophysical analysis of Sepia melanin and dopamine melanin. Two established experimental neuromelanin analogs, melanin from S. officinalis (1 mg/ml) and DAM (1 mg/ml) were qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated. A, Representative images taken of Sepia melanin (left) and DAM suspension (1 mg/ml) using a dark-field microscope with 60× and 100× lenses. Scale bar = 30 µm. B, Finite track-length adjusted plot demonstrating graph of concentration versus size for Sepia melanin (left) and DAM particles obtained using NanoSight. The data represent the average of 5 independent trials of 1 mg/ml solution per trial.

The NTA-generated finite track-length adjusted plot for 1 mg/ml suspensions of Sepia melanin and DAM indicates the distribution of particles by showing the concentration on the y-axis and size on the x-axis (Figure 1B). Table 1 shows specific biophysical properties obtained from NanoSight NTA. As shown in the table, the mean size of Sepia melanin and DAM particles was found to be 172 ± 13.3 and 354 ± 12.7 nm, respectively, whereas median sizes for Sepia melanin and DAM are 137.6 ± 16.2 and 273 ± 9.3 nm, respectively. The D-value (D10, D50, and D90) indicates the distribution intercepts for 10%, 50%, and 90% of the cumulative mass. These data demonstrate that 10%, 50%, and 90% of Sepia melanin particles are under 81.3 ± 4.6, 158 ± 17, and 301 ± 29 nm, respectively, whereas DAM particles are under 205 ± 9.7 nm (D10), 346 ± 10 nm (D50), and 678 ± 26 nm (D90), respectively. Lastly, the data demonstrated that a 1 mg/ml suspension of Sepia melanin or DAM contains about 1.36 ± 0.09 × 108 or 1.78 ± 0.03 × 108 particles, respectively.

Table 1.

Physical Analysis of Sepia Melanin and Dopamine melanin (DAM)

| Melanin | Sepia Melanin | Dopamine Melanin |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Average ± SEM | Average ± SEM |

| Mean (nm) | 172 ± 13.3 | 354.6 ± 12.7 |

| Mode (nm) | 137.6 ± 16.2 | 273.4 ± 9.3 |

| SD (nm) | 85.5 ± 10.4 | 182.5 ± 6.6 |

| D10 (nm) | 81.3 ± 4.6 | 205.3 ± 9.7 |

| D50 (nm) | 158.9 ± 17.2 | 346.9 ± 10.4 |

| D90 (nm) | 301.3 ± 29.5 | 678.4 ± 26.8 |

| Concentration (particles/ml) | 1.36 × 108 ± 9.03 × 106 | 1.78 × 108 ± 3.14 × 106 |

Size and concentration data obtained from NanoSight measurements show average particle size (diameter), size distribution (SD), and particle concentration of Sepia melanin and DAM (1 mg/ml in water) suspension. D10, D50, and D90 values indicate 10%, 50%, and 90% undersize, respectively, indicating (for example) that 50% of Sepia melanin particles are under 158.9 ± 17.2 nm and 50% of DAM particles are under 346.9 ± 10.4 nm in size. The data represent the average of 5 replicates.

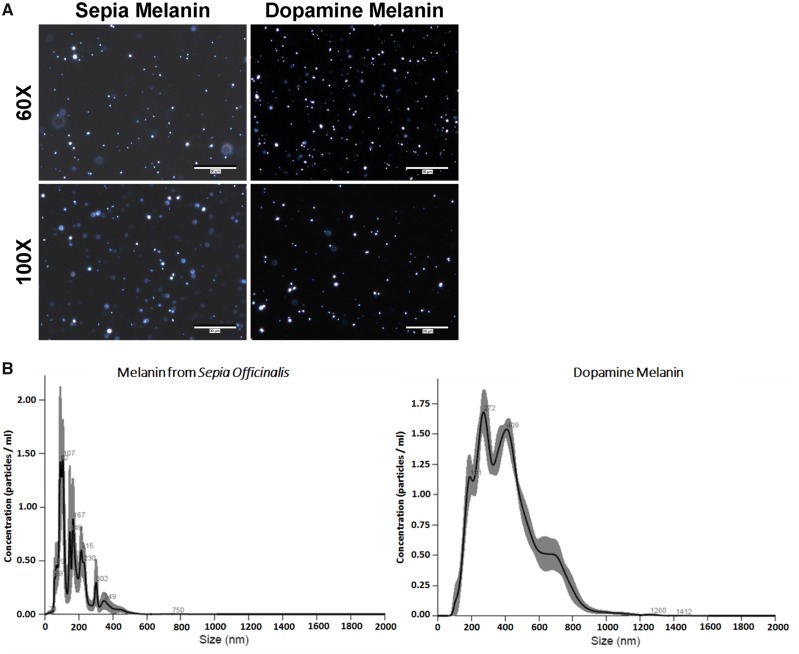

The morphological characterization for Sepia melanin and DAM was further confirmed by SEM on surface structure and TEM (to confirm the morphology obtained from SEM). As shown in Figure 2, both melanin particles were present as agglomerates similar to prior published reports (Costa et al., 2012; Schroeder et al., 2015). Our SEM imaging showed that Sepia melanin particles are spherical in shape with particle size range of approximately 70–200 nm, whereas DAM particles are amorphous in shape with notable particle size between approximately 180 and 400 nm. Furthermore, the surface properties of these 2 melanin particles were also observed to be largely different. Our images showed that Sepia melanin particles exhibited a visibly smooth surface (Figs. 2A and 2C), whereas DAM particles surface was observed to be irregular and rough (Figs. 2B and 2D). In addition, TEM images further confirmed the observations of SEM showing difference in shape, size, and surface quality between Sepia melanin and synthetic DAM particles (Figs. 2E and 2F).

Figure 2.

Electron microscopic images of Sepia melanin and DAM particles. A and C, Representative scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of Sepia melanin particles. B and D, Representative SEM images of DAM particles. Representative transmission electron microscope images of (E) Sepia melanin and (F) DAM. The scale bars in (A, B) denote 1 µm; (B, C) denote 500 nm; and in (E, F) denote 50 nm.

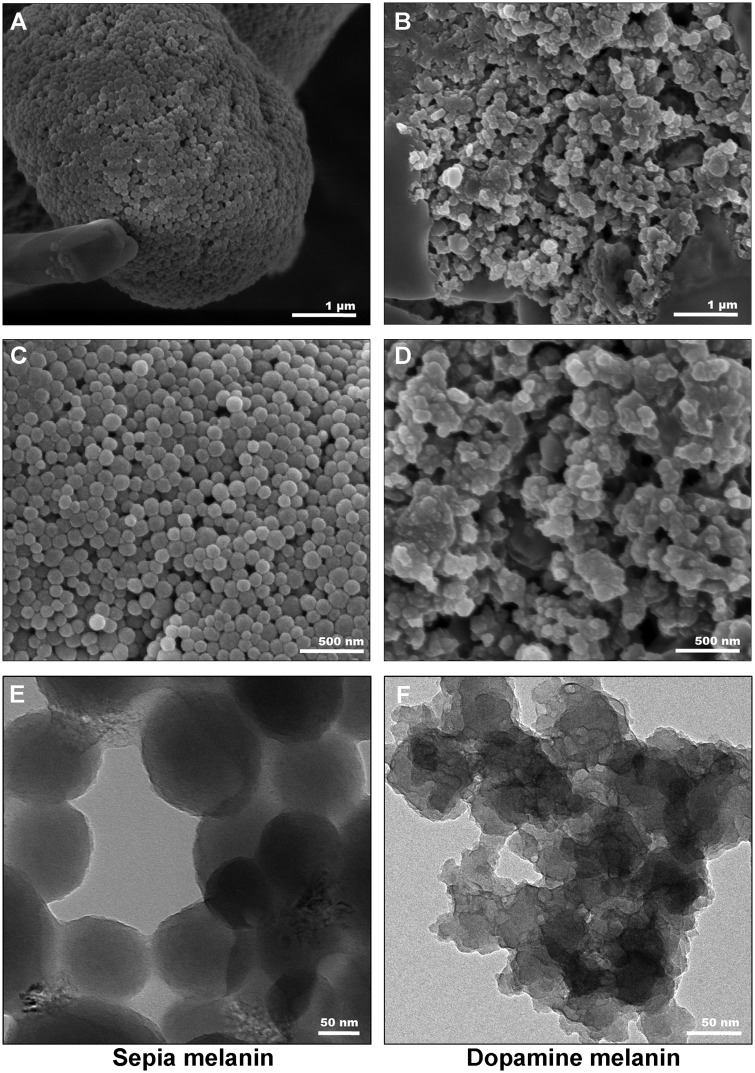

Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines Bind to Neuromelanin-Like Molecules With High Affinity

The data represented in Figure 3 demonstrate saturation-binding curves with Scatchard plots (Figs. 3A, 3C, 3E, and 3G) and plots of percentage of total analyte bound (Figs. 3B, 3D, 3F, and 3H) for harmane and PhIP. The data revealed the maximum binding concentration (Bmax), demonstrating the highest amount of an analyte bound to 1 mg of melanin, and the equilibrium constant (Kd), reporting the concentration of analyte needed to achieve the half-maximum binding. Our data showed Bmax and Kd values for harmane of 1.19 mM/mg Sepia melanin and 0.72 mM for Sepia melanin (Figure 3A), respectively, and Bmax = 3.42 mM/mg DAM and Kd = 1.83 mM for DAM (Figure 3C), respectively. Likewise, for PhIP, the values are Bmax = 273 µM/mg Sepia melanin and Kd = 192 µM for Sepia melanin (Figure 3E), and Bmax = 788 µM/mg DAM and Kd = 430 µM for DAM (Figure 3G), respectively. Furthermore, the data in Figures 3B, 3D, 3F, and 3H demonstrate the % of HAA bound to melanin versus mg of HAA bound to 1 mg of melanin, reporting the maximum amount (in mg) of the analyte bound to 1 mg of melanin. These data show that a maximum of 217 and 622 µg of harmane can bind to 1 mg of Sepia melanin or DAM, respectively. Similarly, a maximum of 65 and 189 µg of PhIP can bind to 1 mg of Sepia melanin or DAM, respectively. Likewise, we also demonstrated that caffeine showed markedly lower binding to Sepia melanin as well as DAM (Supplementary Table 1), as expected for our chosen low-affinity control.

Figure 3.

Binding analysis of harmane and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) to Sepia melanin and dopamine melanin. Concentration-dependent binding analysis of harmane with 1 mg of Sepia melanin (A) and dopamine melanin (DAM) (C); and PhIP with 1 mg Sepia melanin (E) and DAM (G). The graphs on the right represent % of harmane bound to 1 mg of Sepia melanin (B) and DAM (D); and % PhIP bound to 1 mg of Sepia melanin (F) and DAM (H). The data are presented as mean ± SEM for 3 independent experiments, n = 6–9/group.

Next, we showed the % of 100 µM analyte bound to 1 mg of melanin in Table 2. A 70%–88% of all the analytes were bound to Sepia melanin, whereas 87%–95% of these analytes were bound to DAM. The combined data from Figure 3 and Table 2, hence, demonstrate that harmane, PhIP, and active metabolites of PhIP exert firm binding to both neuromelanin analogs consistent with a prior report (Ostergren et al., 2004). In addition, the data show approximately 3-times higher binding of harmane and PhIP to DAM as compared with Sepia melanin.

Table 2.

Heterocyclic Aromatic Amine Binding to Neuromelanin-Like Molecules

| Compound (100 µM) | % Bound to 1 mg Sepia Melanin | % Bound to 1 mg DAM |

|---|---|---|

| Harmane | 84.78 ± 4.23 | 94.18 ± 1.02 |

| PhIP | 87.30 ± 1.06 | 92.6 ± 5.22 |

| 4′-OH-PhIP | 87.73 ± 8.44 | 95.12 ± 3.47 |

| N-OH-PhIP | 74.02 ± 8.34 | 90.15 ± 5.11 |

| NO2-PhIP | 70.53 ± 8.21 | 87.16 ± 11.45 |

| Caffeine | 50.70 ± 7.17 | 52.55 ± 9.56 |

Cell-free spectrophotometric assays were carried out to measure the binding of harmane, PhIP, and active metabolites of PhIP to 1 mg of Sepia melanin or dopamine-associated melanin (DAM). The data represent the % of each analyte bound to different melanins; n = 6–9/group.

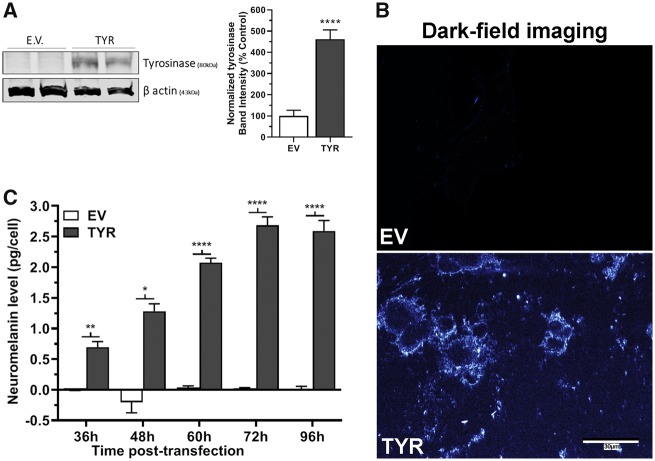

Ectopic Tyrosinase Expression in SH-SY5Y Cells Produces Neuromelanin

The exact mechanisms of neuromelanin biosynthesis are not clearly understood and the biochemistry of formation has been highly debated (Wakamatsu et al., 2012; Zecca et al., 2003). Although tyrosinase may have a limited role in producing neuromelanin in vivo, data from previous studies suggest that dopamine metabolism in the presence of tyrosinase enzyme can lead to neuromelanin production and ectopic tyrosinase expression has proven to be useful in modeling neuromelanin production (Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2019; Hasegawa, 2010). Furthermore, tyrosinase, a copper-containing metalloprotein, can oxidize dopamine to form melanin pigments, probably through dopamine-o-quinone (Miranda et al., 1984). Recent studies suggest that ectopic expression of tyrosinase leads to neuromelanin production in vitro (Hasegawa, 2010; Hasegawa et al., 2008) and in rodent brain (Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2019). Thus, ectopic tyrosinase expression is 1 strategy to produce neuromelanin in otherwise deficient biological systems. To ensure that a commonly used strategy to increase neuromelanin was efficacious in our system, we characterized the impact of ectopic tyrosinase expression. Ross and Biedler (1985) reported lack of detectable levels of tyrosinase in SH-SY5Y cells. Accordingly, our Western blot data showed that only tyrosinase-transfected cells had expression of tyrosinase (Figure 4A) indicating successful transfection and protein translation.

Figure 4.

Formation of neuromelanin in tyrosinase-overexpressing SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. A, Representative immunoblot showing expression of tyrosinase (TYR, 80 kDa) in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with empty vector (EV) or TYR constructs for 48 h. β-actin (43 kDa) used as a loading control. The bar histogram represents the normalized densitometry of tyrosinase in EV- and TYR-transfected cells. The data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 4/group, analyzed using unpaired t test. ****p < .0001 compared with EV group. B, Representative dark-field microscopic image of EV or TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells at 48 h, demonstrating the formation of melanin in TYR SH-SY5Y cells. Scale bar = 30 µm. C, Estimated amount of neuromelanin per EV and TYR SH-SY5Y cell after 36, 48, 60, 72, and 96 h post-transfection. Neuromelanin levels were quantified by solubilizing cells in basic buffer at 80°C for 2 h then measuring absorbance at 470 nm. Sepia Melanin was used to generate a standard curve. The data represented as mean ± SEM of pg/cell values (n = 6/group), analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test. *p < .05, **p < .01, and ****p < .0001 comparing EV- versus TYR-*transfected SH-SY5Y cells at a given time post-transfection.

After 48 h of transfection, formation of neuromelanin-like light-diffracting particulates was only apparent in TYR-transfected cells (Figure 4B). Next, we estimated the amount of neuromelanin formed/cell after 36–96 h of transfection. Our data reveal that starting at 36 h, the tyrosinase-transfected cells contained about 0.67 pg of neuromelanin per cell, which increased as high as 2.65 pg/cell at 72 h post-transfection (Figure 4C). In contrast, as expected, EV-transfected SH-SY5Y cells had no detectable neuromelanin formation. We further demonstrated the formation of neuromelanin using dark-field microscopy.

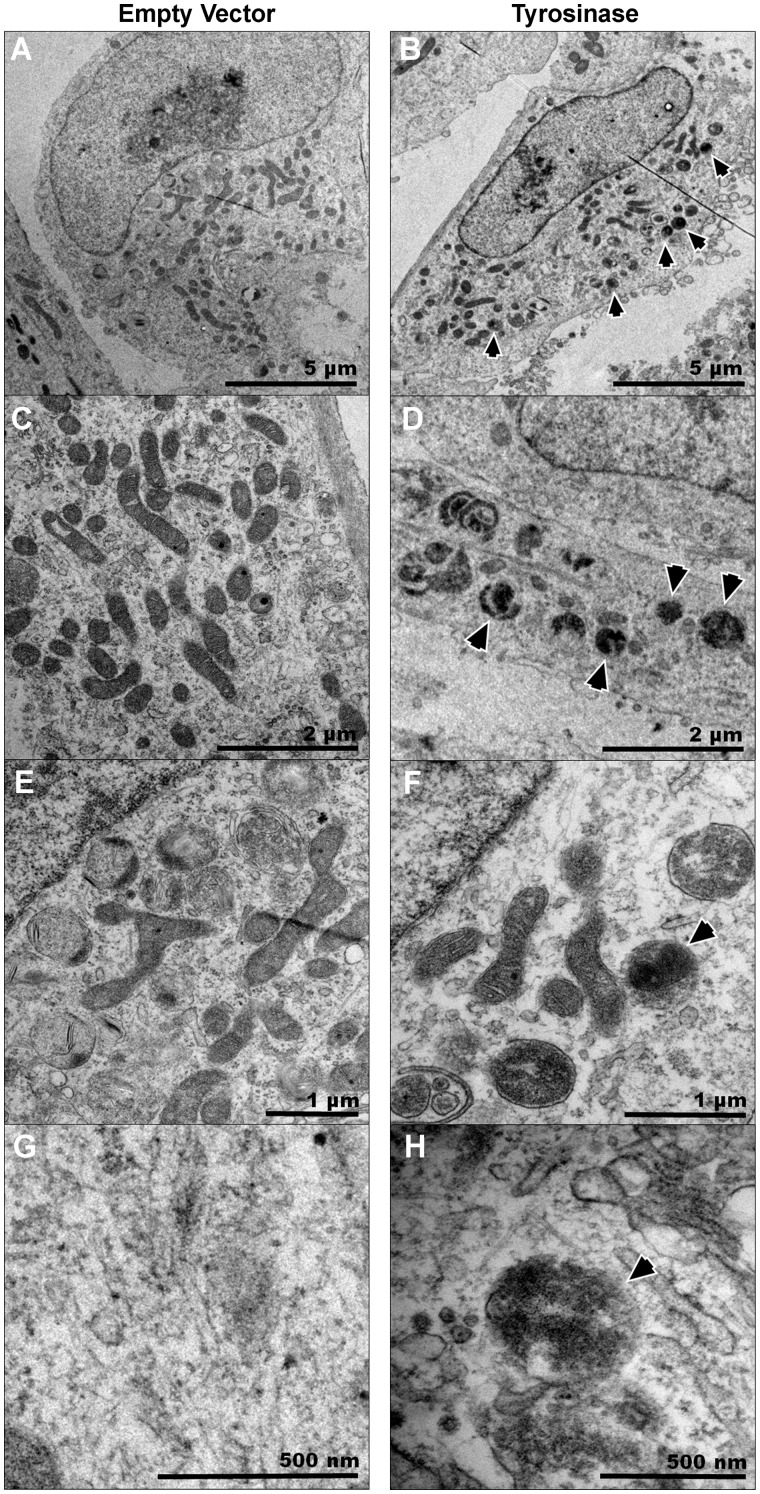

The presence of melanin particles was then further confirmed using electron microscopy. The Figure 5 shows the TEM images of EV- or tyrosinase-transfected SH-SY5Y cells at different magnification. The images clearly showed the presence of dense-black pigments in tyrosinase-transfected cells. Burbulla et al. (2017) recently showed neuromelanin formation in vitro in iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from familial PD patients. Our data show similar pigments in tyrosinase-expressing SH-SY5Y cells (Figs. 5B, 5D, 5F, and 5H). Notably, there was no expression of similar dark pigments in EV-transfected cells (Figs. 5A, 5C, 5E, and 5G), further indicating neuromelanin formation.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopic observation of SH-SY5Y cells shows neuromelanin pigments. SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or tyrosinase (TYR) constructs and 48 h post-transfection, cells were fixed for TEM. A, C, E, and G, Representative images of EV SH-SY5Y cells taken with an FEI/Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope at different magnifications. B, D, F, and H, Representative TEM images of TYR SH-SY5Y cells taken using an FEI/Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope shows the presence of dark-black pigments. The scale bars in denote 5 µm in (A, B); 2 µm in (C, D); 1 µm in (E, F); 500 nm in (G, H). The arrows point toward intracellular neuromelanin pigments in TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells.

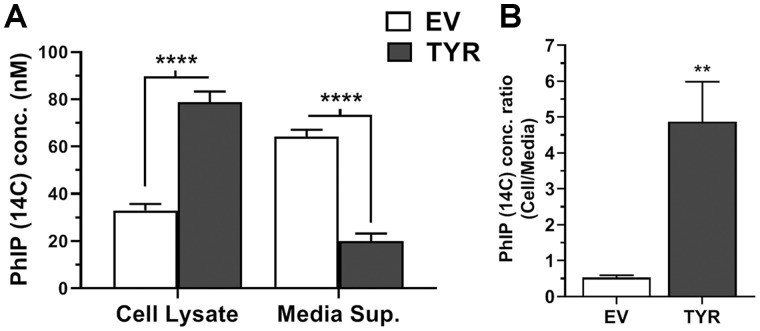

Neuromelanin Formation Increases Cellular PhIP Levels

Our data revealed that EV SH-SY5Y cells (lacking neuromelanin) contained 30%–35% of total 14C-PhIP (relative to media + cellular levels), whereas TYR SH-SY5Y cells (forming neuromelanin) contained significantly greater radiolabeled PhIP levels (p < .0001), up to 74%–82% of total exposed 14C-PhIP (Figure 6A). Furthermore, ratiometric analyses revealed that the ratio of cellular PhIP to media PhIP increased by approximately 9-fold in neuromelanin-forming cells (4.9 ± 2.4) versus EV (0.5 ± 0.2) (Figure 6B). These data show that neuromelanin increases intracellular PhIP levels.

Figure 6.

Increased intracellular 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) uptake in neuromelanin-forming SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or tyrosinase (TYR) for 48 h followed by treatment with 100 nM radiolabeled PhIP (14C) for 24 h. Post-treatment, cell lysates and media supernatants were analyzed for 14C radioactivity using PerkinElmer TRI-CARB 4910TR 110V Liquid Scintillation Counter. The standard curve was obtained and PhIP concentrations were determined in cell lysates and media concentrations, based on relative cpms. A, Radiolabeled PhIP (14C) levels in cells versus in treatment media. B, Ratio of accumulated PhIP (14C) in cells to treatment media after 24 h of exposure. The data represented as mean ± SEM for experiment performed at least in triplicate. Statistical analysis performed using 2-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test for (A) and unpaired t test for (B). **p < .01 and ****p < .0001 comparing EV- versus TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells treated with 14C-PhIP (n = 6/group).

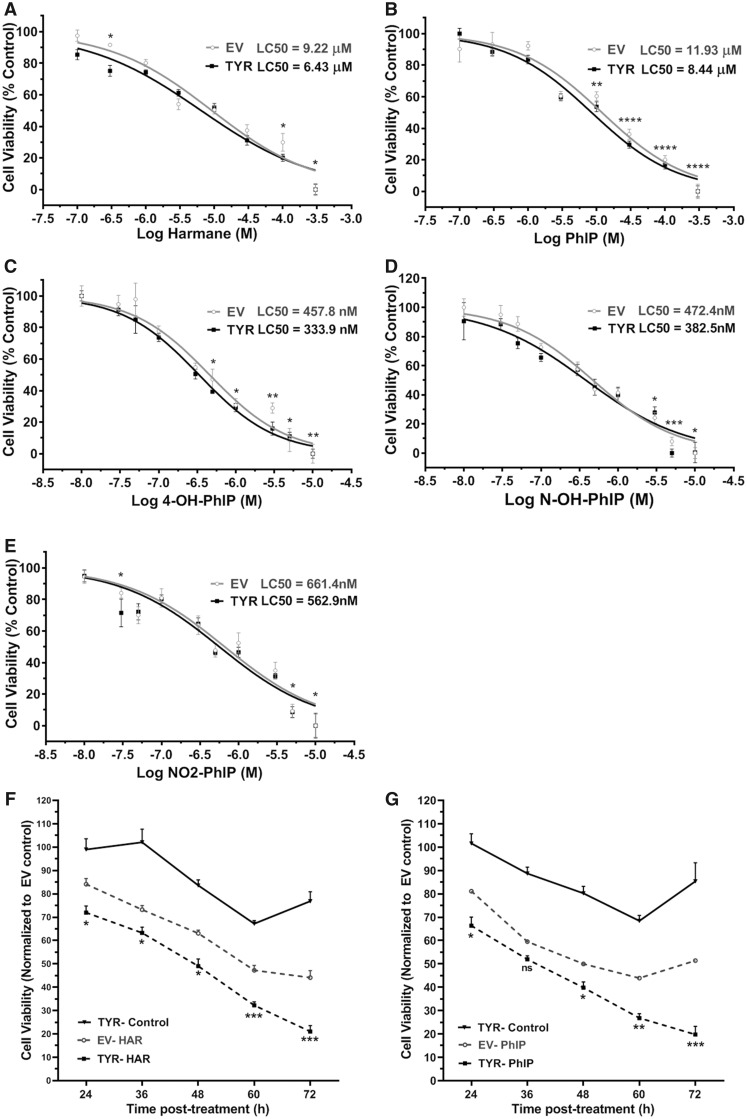

Neuromelanin Forming SH-SY5Y Cells Exhibit Heightened HAA-Induced Neurotoxicity

Cell viability dose-response curves for harmane and PhIP (100 nM–300 μM) and PhIP metabolites (4′-OH PhIP, N-OH-PhIP, and NO2-PhIP; 10 nM–10 μM) (24 h treatment) revealed modest, but significant differences between EV and tyrosinase transfected cells (Figs. 7A–E). The LC50 values for each toxicant are reported on respective graphs for SH-SY5Y cells with or without neuromelanin formation and reveal about 30%–40% leftward shift of LC50 in cells forming neuromelanin versus no melanin. This indicates that neuromelanin-forming SH-SY5Y cells are more sensitive to HAA-mediated cell death compared with cells without neuromelanin. These results led us to conduct time-course experiments. Thus, we treated SH-SY5Y cells with a sublethal concentration (10 μM) of harmane and PhIP for 24–72 h. At 24 h, neuromelanin-forming SH-SY5Y cells showed significantly lower (p < .05) cell viability (approximately 10%) compared with SH-SY5Y cells without neuromelanin in response to HAA treatment (Figs. 7F and 7G). At 72 h post-treatment, the difference of cell viability between EV- and TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 μM harmane or PhIP increased to 28%–40% (p < .001), further suggesting a sensitizing effect of neuromelanin in HAA-mediated neuronal cell death. Intriguingly, we also noted a time-dependent loss of cell viability with neuromelanin formation without exposure to any neurotoxicant, suggesting that there could be a cytotoxic effect of neuromelanin in SH-SY5Y cells. To confirm cytotoxicity, we also assessed cell death through a different mechanism by a DNA fragmentation assay. This data showed a similar magnitude of cell death with very similar LC50 values, confirming that PhIP exposure produced greater cell death in TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells versus EV-transfected SH-SY5Y cells (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 7.

Decreased cell viability in neuromelanin-forming, heterocyclic aromatic amine (HAA)-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Galactose supplemented SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or tyrosinase (TYR). Post 48 h of transfection, cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of (A) harmane, (B) 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), (C) 4′-OH PhIP, (D) N-OH-PhIP, or (E) NO2-PhIP for 24 h. An MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability, and dose-response curves were obtained for EV or TYR cells. Calculated LC50 are mentioned in each graph for respective toxicants. The data represented as mean ± SEM for each treatment group performed in triplicate with n = 9. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, and ****p < .0001 comparing EV- versus TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells at a given HAA concentration. F and G, Time-dependent cell death of EV and TYR SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 µM harmane and 10 µM PhIP, respectively. The data represented as mean ± SEM for n = 6, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, and ****p < .0001 compared with SH-SY5Y cells transfected with EV at 24 h. Abbreviation: ns, nonsignificant.

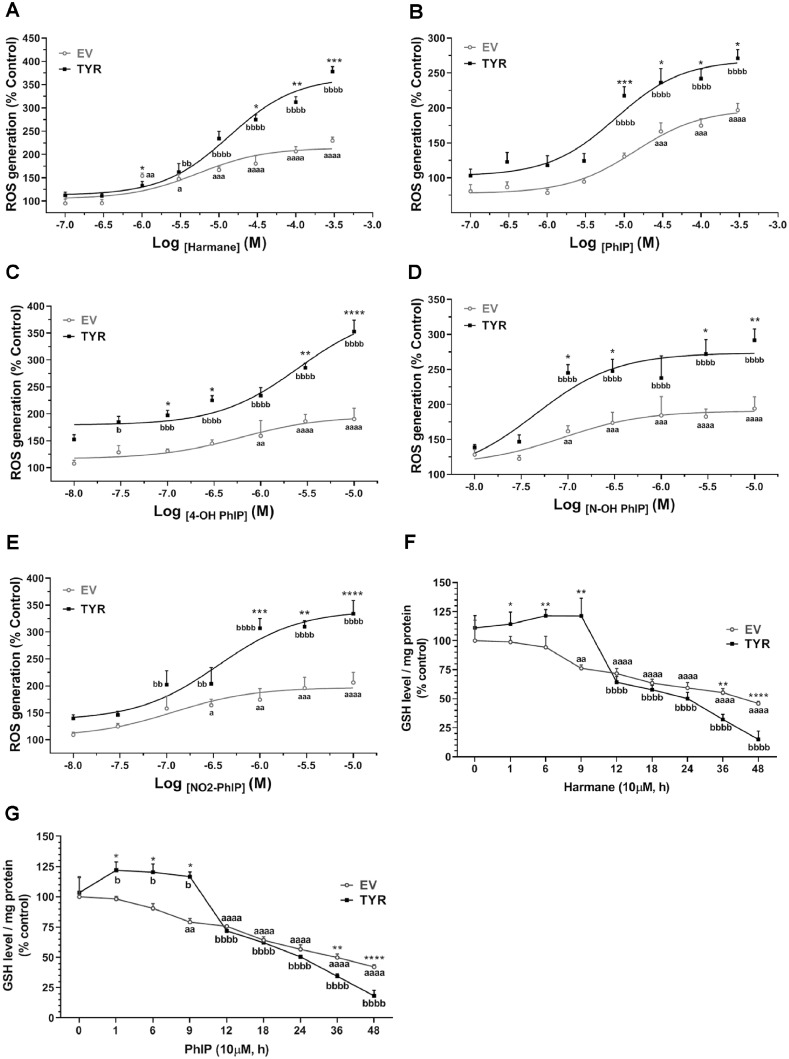

Neuromelanin Modulates HAA-Induced Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress and resultant damage is a key mechanism of PD-relevant neurodegeneration (Cannon et al., 2009; Jenner, 1998; Puspita et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2018). Furthermore, several antioxidants have been shown to alleviate neuronal loss and have been proposed as potential therapies for PD treatment in preclinical studies (Jiang et al., 2016; Sarrafchi et al., 2015). ROS quantification revealed a dose-dependent increase in ROS levels in HAA-treated cells with or without neuromelanin (Figs. 8A–E). In cells without neuromelanin formation, the increase in ROS levels was detected in cells exposed to harmane at a concentration as low as 1 μM, with about a approximately 1.6-fold increase under these conditions compared with untreated EV control cells (p < .01), leading up to approximately 3.5-fold increase at 300 μM harmane (p < .0001) (Figure 8A). Likewise, neuromelanin-forming cells exhibited a 1.6-fold increase in ROS generation upon exposure to 3 μM harmane (p < .01), further increasing to at least a 4.2-fold increase upon exposure to 300 μM harmane (p < .0001) (Figure 8A). Importantly, cells forming neuromelanin showed significantly greater ROS levels at 30, 100, and 300 μM harmane treatments compared with cells without neuromelanin with the same treatment dose (Figure 8A). Similar trends were reported with treatments of PhIP and PhIP metabolites, where clear increases in toxicity were apparent in neuromelanin forming cells (Figs. 8B–E). Notably, metabolites of PhIP caused ROS generation at very lower doses, which can be attributed to their rapid oxidation, generating less stable metabolite (Turesky and Le Marchand, 2011). Glutathione is a key cellular antioxidant tri-peptide, which quenches intracellular oxidative free radicals by forming dithiol bond (Liddell and White, 2018; Schulz et al., 2000). Time-dependent GSH depletion was also apparent in response to HAAs in EV SH-SY5Y cells, whereas in tyrosinase cells, GSH levels were increased at earlier time-points followed by marked loss starting at 12 h. At the 12 h time-point, an approximately 20%–28% decrease in GSH levels was reported in SH-SY5Y cells with or without neuromelanin (Figs. 8F and 8G). Interestingly, at later time-points (36 and 48 h), the HAA-mediated decrease in GSH levels in neuromelanin-forming cells was significantly greater than that in cells without neuromelanin formation (Figs. 8F and 8G).

Figure 8.

Neuromelanin formation increases heterocyclic aromatic amine-induced oxidative damage. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with tyrosinase (TYR) to form neuromelanin in vitro, whereas empty vector (EV)-transfected cells were used as control cells. Empty vector and TYR SH-SY5Y cells were treated with varying concentrations of different toxicants. Post 24 h treatment, intracellular ROS levels were measured using CM-H2DCFDA fluorogenic dye. Dose-dependent alterations of ROS levels in EV and TYR SH-SY5Y cells exposed to (A) harmane, (B) 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), (C) 4′-OH PhIP, (D) N-OH-PhIP, and (E) NO2-PhIP were recorded as % control of observed relative fluorescence unit. The data presented as mean ± SEM for experiment performed at least twice independently, n = 6–8, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test to determine significance. ap < .05, aap < .01, aaap < .001, and aaaap < .0001 compared with EV at 0 h; bp < .05, bbp < .01, bbbp < .001, and bbbbp < .0001 compared with TYR at 0 h; whereas, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, and ****p < .0001 demonstrate significant difference between EV- versus TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells at a given time-point. Changes in levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) at various time-points in EV and TYR SH-SY5Y cells exposed to (F) 10 µM harmane and (G) 10 µM PhIP, respectively. The data were calculated as % of EV control group and represented as mean ± SEM, n = 4 per group, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test. ap < .05, aap < .01, aaap < .001, and aaaap < .0001 compared with EV at 0 h; bp < .05, bbp < .01, bbbp < .001, and bbbbp < .0001 compared with TYR at 0 h; whereas, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, and ****p < .0001 demonstrate significant difference between EV- versus TYR-transfected SH-SY5Y cells at a given time-point.

In addition, we observed increases in protein oxidation by 3-NT quantification. Here, we noted up to a 1.4-fold increase in 3-NT levels in EV-transfected SH-SY5Y cells treated with 10 μM PhIP relative to control cells (EV-transfected, not treated with PhIP) (Figure 9). Following a similar trend, we further noted that PhIP-treated cells forming neuromelanin showed more than a 2.2-fold increase in 3-NT levels relative to untreated, vector control cells (Figure 9). Finally, dark-field microscopy further confirmed the presence of neuromelanin in TYR cells as in other experiments.

Figure 9.

Neuromelanin increases 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) in heterocyclic aromatic amine-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Post-transfection with empty vector (EV) or tyrosinase (TYR) for 48 h, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were treated with 10 µM 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) for 24 h. Post-treated, fixed cells were imaged using a dark-field microscope under a 60× lens. Cells were labeled with actin (red) and 3-NT (green) using specific antibodies. Neuromelanin images were converted to “magenta” color using ImageJ. Hoechst was used to mark the chromatin nucleus (blue). Merged images on the extreme right show all channels. Inset from each demonstrates marked regions. Scale bar = 30 µm. For quantification, 3-NT fluorescence intensities were measured in regions of interest surrounding each cell. Data presented as the mean ± SEM; analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison post hoc test, *p < .05 and ****p < .0001 compared with EV control; ΔΔp < .01 compared with TYR control; whereas ##p < .01 compares EV and TYR cells treated with PhIP.

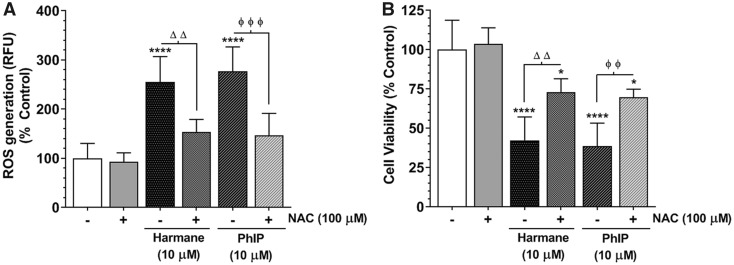

N-acetyl Cysteine Reduces HAA-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cell Death

Antioxidant supplementation in the form of NAC (100 µM, 1 h) pretreatment markedly ameliorated HAA-induced ROS generation close to baseline levels in SH-SY5Y cells forming neuromelanin (p < .01, Figure 10A). In addition, Figure 10B shows that NAC pretreatment also reduced the cell death in neuromelanin-forming SH-SY5Y cells treated with harmane or PhIP (10 µM, 24 h). These data indicate that oxidative stress may play a crucial role in modulating HAA-mediated cell death mechanisms in dopaminergic cells producing neuromelanin.

Figure 10.

N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) alleviates heterocyclic aromatic amine (HAA)-induced toxicity in neuromelanin forming SH-SY5Y cells. After 48 h of transfection, the tyrosinase (TYR) overexpressing SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with NAC (100 µM) for 1 h followed by treatment with 10 µM 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) or 10 µM harmane for 24 h. A, Assessment of ROS levels in TYR SH-SY5Y cells pretreated with NAC (100 µM, 1 h) followed by HAA treatment. Changes in relative fluorescence unit values were plotted as % control and represented as mean ± SEM, n = 8/group. B, Cell death was assessed using MTT assay in PhIP or harmane-treated TYR SH-SY5Y cells, with or without NAC pretreatment. The cell viability was presented as % of vehicle-treated control group and represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6–8/group. ****p < .0001 compared with non-treated control group; ΔΔp < .001 denotes significance between harmane-treated groups with or without NAC pre-exposure; whereas ϕϕp < .001 and ϕϕϕp < .0001 denote significance between PhIP-treated groups with or without NAC pre-exposure.

DISCUSSION

Heterocyclic aromatic amines are putative dopaminergic neurotoxins (Agim and Cannon, 2018; Cruz-Hernandez et al., 2018; Sammi et al., 2018). Here, we studied the role of neuromelanin in modulating HAA neurotoxicity. Our data demonstrate that HAAs bind to experimental neuromelanin analogs. Furthermore, neuromelanin formation increases the intracellular neuronal levels of PhIP. Finally, neuromelanin-forming neurons showed higher sensitivity to HAA-mediated cell death, accompanied by higher oxidative damage. The results are significant for 2 major reasons: (1) potential mechanism of accumulation and neurotoxicity is identified for HAA-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity; (2) the results point to a specific translational weakness of commonly utilized PD models that lack neuromelanin; such models likely underestimate risk indicating that systems forming neuromelanin are needed to study PD-relevant neurotoxicity.

We provide a plausible mechanism by which underlying dopaminergic neurobiology may contribute to selective HAA neurotoxicity. It is worth noting that our previous studies showing selective neurotoxicity of HAAs were conducted in cellular and animal model systems with poor formation of neuromelanin, where HAAs-induced oxidative stress in all neurons, with a magnified response in dopamine neurons (Agim and Cannon, 2018; Cruz-Hernandez et al., 2018). Thus, the findings of our study suggest that organisms forming higher levels of neuromelanin would accumulate higher levels of intracellular HAAs, with induction of neurotoxicity at lower doses relative to organisms lacking neuromelanin.

Human studies show that there is a greater loss of neuromelanin-forming dopamine neurons than non-neuromelanin forming dopamine neurons in PD patients, along with actual neuromelanin loss, suggesting that neuromelanin may have a role in selective sensitivity of dopaminergic subpopulations in PD (Sulzer et al., 2018; Wakamatsu et al., 2012; Zecca et al., 2002). Moreover, a recent study in mice showed that ectopic neuromelanin formation through viral-vector delivered tyrosinase produces PD-relevant neuropathology (Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2019). That study is particularly important because it shows that ectopic neuromelanin formation can be produced in rodents with strikingly similar biophysical properties to human neuromelanin.

Although clearly important, the role of neuromelanin has largely been ignored in examining potential PD risk factors. Given that rodents and many in vitro cell culture models form negligible neuromelanin, such models have a significant translational weakness, where at a minimum, there is likely decreased cellular toxin accumulation (vs humans), with a potential underestimate of neurotoxic risk (Aimi and McGeer, 1996; Hasegawa, 2010).

Our biophysical analysis produced similar values for the Sepia melanin particle size (mean = 172 nm) compared with the previous reports, suggesting utility for initial binding assays (Liu and Simon, 2005). Furthermore, Bridelli (1998) showed that melanin synthesized through autoxidation has an average radius size of 191 nm. Similarly, our data revealed a mean size of 354.6 nm with a D50 value of 346.9 nm for synthetic DAM particles. In addition, our data demonstrate that synthetic DAM has about 4.2 × 107 more particles compared with Sepia melanin at a mass of 1 mg. To our knowledge, the information on size distribution and particle count for these analogs has been not reported previously and might be helpful in further establishing these melanins as models for neuromelanin in PD research.

A recent study reported that PhIP, but not other prototypical HAAs produced in cooked meat, bind to melanin and other pigments in the human hair follicle suggesting hair as a specimen for biomonitoring PhIP (Turesky et al., 2013). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that nicotine and dopamine bind to Sepia melanin, whereas caffeine (mM levels) does not appreciably bind. Similarly, using analogous concentrations (Haining et al., 2016), we found lower binding with caffeine compared with HAAs, confirming that not all ringed, nitrogen-containing compounds bind with high affinity. Indeed, our data show that harmane, PhIP and PhIP metabolites bind to both melanins with strong affinity. However, the maximum amounts of analyte bound to Sepia melanin and DAM differ. Our data show that as much as 3-times more HAAs bind to DAM in comparison with Sepia melanin. Based on Bmax values, we showed that 1 mg of Sepia melanin can bind to a maximum of 65 µg of PhIP, whereas the same mass of DAM can bind up to 189 µg PhIP. These data further distinguish the 2 analogs proposed for studying neuromelanin interactions. It is possible that a larger particle size, a higher number of particles in 1 mg of DAM, compared with Sepia melanin, and difference in surface qualities of melanin particles might be responsible for higher binding affinities. Together, the 2 neuromelanin analogs represent an initial screening platform to identify potential neurotoxicants via their binding to neuromelanin, leading to a rationale for studies in biological systems. Prior studies have suggested toxin-neuromelanin association through binding in cell-free assays and radiolabeling of tissue sections. Here, our findings confirm and advance understanding of these associations (Ostergren et al., 2004). Furthermore, we provide direct quantitative evidence that neuromelanin formation increases intracellular HAA levels.

Multiple dopaminergic neurotoxicants have been shown to bind to neuromelanin (D'Amato et al., 1986; Karlsson et al., 2009; Langston et al., 1999; Lindquist et al., 1988; Ostergren et al., 2007). However, how these interactions may alter dopaminergic neurotoxicity has not been investigated in detail; instead, most studies have been carried out in systems lacking neuromelanin. Using a previously established ectopic tyrosinase expression technique to foster neuromelanin formation (Hasegawa, 2010), we were able to show clear evidence of tyrosinase-induced neuromelanin formation through biochemical, histological, and TEM examinations. Interestingly, similar to our cell-free assays, we demonstrated that neuromelanin-forming cells exhibit significantly greater HAA uptake. Our prior study showed that PhIP is not a substrate for the dopamine transporter, suggesting that increased intracellular levels are directly due to interactions with neuromelanin (Griggs et al., 2014).

A recent epidemiological study revealed that humans consuming higher HAAs by means of eating meat cooked at higher temperature have a marked increase in plasma levels of malondialdehyde, a known marker of oxidative stress (Carvalho et al., 2015). In addition, several studies in various disease models suggest that HAAs have pro-oxidant effects (Gonzalez, 2005; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Haza and Morales, 2011; Karim et al., 2003; Tafazoli et al., 2005). Our current data show that HAAs act as oxidative stressors in dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells and that neuromelanin formation potentiates such oxidative damage. Furthermore, we demonstrated that pretreatment by an antioxidant, NAC, reduces HAA-mediated oxidative stress and cell death, suggesting that HAAs can attack cellular defense mechanisms to generate more reactive free radicals, leading to increased accumulation of ROS causing oxidative damage, production of 3-NT by nitrosative stress, and reduced GSH levels.

Our previous studies primarily focused on harmane and PhIP as dopaminergic neurotoxins (Griggs et al., 2014; Sammi et al., 2018). 4′-OH PhIP and N-OH-PhIP are 2 major PhIP metabolites formed in rodents, with N-OH-PhIP, a genotoxic metabolite capable of forming covalent adducts to DNA and protein, found to be neurotoxic and present in brain of mice (Enokizono et al., 2008; Griggs et al., 2014; Sammi et al., 2018; Teunissen et al., 2010; Turesky and Le Marchand, 2011). In humans, PhIP undergoes extensive N-oxidation to form N-OH-PhIP as the major pathway of metabolism (Turteltaub et al., 1999). In addition, NO2-PhIP, is an active intermediate metabolite, which can undergo reduction to form N-OH-PhIP (Frandsen et al., 1991). In contrast, 4′-HO-PhIP is viewed as a detoxified metabolite with regard to genotoxicity (Langouet et al., 2002). Cells were more sensitive to PhIP metabolites both in terms of LC50 (approximately 20× lower LC50) and oxidative stress (> 2× magnitude at identical doses), suggesting that the role of metabolism in neurotoxicity should be further investigated.

The most significant weakness of this study is the utilization of a neuronal cell line, in the absence of animal studies. As expected, transformed cells were less sensitive to HAAs (higher doses required) than primary neurons (Cruz-Hernandez et al., 2018). Nevertheless, SH-SY5Y cells offer an ideal system to ectopically form neuromelanin and conduct mechanistic studies. Indeed, a major goal of this study was to address translational weaknesses of current cellular and animal models. Thus, the conclusions of this study and other reports in the literature highlight the critical need to utilize models forming neuromelanin in neurotoxicity studies. A recent report suggests that rodent models forming neuromelanin may have greater translational value (Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2019). Such approaches involving the production of neuromelanin in rodent models are likely to have great value in the study of PD due to their increased relevance to human neurobiology.

It is also worth noting that multiple aspects of dopamine catabolism may contribute to neurotoxicity. Oxidized dopamine and aminochrome are 2 of the key intermediates of neuromelanin formation. Both of these products can themselves induce dopaminergic neurotoxicity (Burbulla et al., 2017; Segura-Aguilar and Huenchuguala, 2018). However, our time-course analysis showed that tyrosinase-transfected cells did not exhibit cell death up to 84 h post-transfection. Because, all of our treatments were within 72 h of transfection, we infer that toxicity observed in tyrosinase-transfected cells is due to neuromelanin-related increased HAA accumulation in cells. In addition, we noted reduced cell viability in neuromelanin forming cells from 96 h post-transfection. Interestingly, a recent in vivo study reported similar trend of age-dependent cell death in tyrosinase-mediated neuromelanin presenting dopaminergic neurons (Carballo-Carbajal et al., 2019). That study further showed a potential role of impaired mitochondrial respiration and dysfunctional autophagolysosomal system as mechanisms of cell death.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that neuromelanin binds to HAAs, and neuromelanin-forming neurons are more sensitive to HAA-induced neurotoxicity. These data suggest that neuromelanin could be critical for selective dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Given that many dopaminergic toxins bind strongly to neuromelanin, these results likely have broader implications beyond HAA-neurotoxicity, where models with increased human relevance should be utilized in general to study dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author/authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Life Science Microscopy Facility (LSMF), Purdue University for helping us with electron microscopy. We would specially thank the facility director Dr Christopher J. Gilpin and research assistants Robert Seiler and Laurie Mueller, for providing training for using electron microscopes and preparing samples.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (R01ES025750 to J.R.C.); the Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust (to J.R.C.); and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01CA122320 to R.J.T.).

REFERENCES

- Adamson S. X., Lin Z., Chen R., Kobos L., Shannahan J. (2018). Experimental challenges regarding the in vitro investigation of the nanoparticle-biocorona in disease states. Toxicol. In Vitro 51, 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agim Z. S., Cannon J. R. (2015). Dietary factors in the etiology of Parkinson's disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agim Z. S., Cannon J. R. (2018). Alterations in the nigrostriatal dopamine system after acute systemic PhIP exposure. Toxicol. Lett. 287, 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimi Y., McGeer P. L. (1996). Lack of toxicity of human neuromelanin to rat brain dopaminergic neurons. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albores R., Neafsey E. J., Drucker G., Fields J. Z., Collins M. A. (1990). Mitochondrial respiratory inhibition by N-methylated beta-carboline derivatives structurally resembling N-methyl-4-phenylpyridine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 9368–9372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayles A. V., Squires T. M., Helgeson M. E. (2016). Dark-field differential dynamic microscopy. Soft Matter 12, 2440–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridelli M. G. (1998). Self-assembly of melanin studied by laser light scattering. Biophys. Chem. 73, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulla L. F., Song P., Mazzulli J. R., Zampese E., Wong Y. C., Jeon S., Santos D. P., Blanz J., Obermaier C. D., Strojny C. (2017). Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Science 357, 1255–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush W. D., Garguilo J., Zucca F. A., Albertini A., Zecca L., Edwards G. S., Nemanich R. J., Simon J. D. (2006). The surface oxidation potential of human neuromelanin reveals a spherical architecture with a pheomelanin core and a eumelanin surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14785–14789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J. R., Greenamyre J. T. (2011). The role of environmental exposures in neurodegeneration and neurodegenerative diseases. Toxicol. Sci. 124, 225–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J. R., Tapias V., Na H. M., Honick A. S., Drolet R. E., Greenamyre J. T. (2009). A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Carbajal I., Laguna A., Romero-Giménez J., Cuadros T., Bové J., Martinez-Vicente M., Parent A., Gonzalez-Sepulveda M., Peñuelas N., Torra A. (2019). Brain tyrosinase overexpression implicates age-dependent neuromelanin production in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Nat. Commun. 1, 973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A. M., Miranda A. M., Santos F. A., Loureiro A. P. M., Fisberg R. M., Marchioni D. M. (2015). High intake of heterocyclic amines from meat is associated with oxidative stress. Br. J. Nutr. 113, 1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charkoudian L. K., Franz K. J. (2006). Fe(III)-coordination properties of neuromelanin components: 5,6-Dihydroxyindole and 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid. Inorg. Chem. 45, 3657–3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang S. M., Hernan M. A., Willett W. C., Ascherio A. (2002). Diet and Parkinson's disease: A potential role of dairy products in men. Ann. Neurol. 52, 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T. G., Younger R., Poe C., Farmer P. J., Szpoganicz B. (2012). Studies on synthetic and natural melanin and its affinity for Fe(III) ion. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2012, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Hernandez A., Agim Z. S., Montenegro P. C., McCabe G. P., Rochet J. C., Cannon J. R. (2018). Selective dopaminergic neurotoxicity of three heterocyclic amine subclasses in primary rat midbrain neurons. Neurotoxicology 65, 68–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amato R. J., Alexander G. M., Schwartzman R. J., Kitt C. A., Price D. L., Snyder S. H. (1987). Neuromelanin: A role in MPTP-induced neurotoxicity. Life Sci. 40, 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amato R. J., Lipman Z. P., Snyder S. H. (1986). Selectivity of the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP: Toxic metabolite MPP+ binds to neuromelanin. Science 231, 987–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie C. A. (2008). A review of Parkinson's disease. Br. Med. Bull. 86, 109–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rus Jacquet A., Timmers M., Ma S. Y., Thieme A., McCabe G. P., Vest J. H. C., Lila M. A., Rochet J. C. (2017). Lumbee traditional medicine: Neuroprotective activities of medicinal plants used to treat Parkinson's disease-related symptoms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 206, 408–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Double K. L., Zecca L., Costi P., Mauer M., Griesinger C., Ito S., Ben-Shachar D., Bringmann G., Fariello R. G., Riederer P., et al. (2008). Structural characteristics of human substantia nigra neuromelanin and synthetic dopamine melanins. J. Neurochem. 75, 2583–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker G., Raikoff K., Neafsey E. J., Collins M. A. (1990). Dopamine uptake inhibitory capacities of beta-carboline and 3,4-dihydro-beta-carboline analogs of N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) oxidation products. Brain Res. 509, 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet J., Ducommun M., Zollinger M., Kellenberger E. (1971). A new preparation method for dark-field electron microscopy of biomacromolecules. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 35, 147–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enokizono J., Kusuhara H., Ose A., Schinkel A. H., Sugiyama Y. (2008). Quantitative investigation of the role of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) in limiting brain and testis penetration of xenobiotic compounds. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36, 995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorow H., Tribl F., Halliday G., Gerlach M., Riederer P., Double K. L. (2005). Neuromelanin in human dopamine neurons: Comparison with peripheral melanins and relevance to Parkinson's disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 75, 109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen H., Rasmussen E. S., Nielsen P. A., Farmer P., Dragsted L., Larsen J. C. (1991). Metabolic formation, synthesis and genotoxicity of the N-hydroxy derivative of the food mutagen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo (4,5-B) pyridine (PhIP). Mutagenesis 6, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb W. R. G. (1992). Melanin, tyrosine-hydroxylase, calbindin and substance-P in the human midbrain and substantia-nigra in relation to nigrostriatal projections and differential neuronal susceptibility in Parkinsons-disease. Brain Res. 581, 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F. J. (2005). Role of cytochromes P450 in chemical toxicity and oxidative stress: Studies with CYP2E1. Mutat. Res. 569, 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P., da Costa V. C. P., Hyde K., Wu Q., Annunziata O., Rizo J., Akkaraju G., Green K. N. (2014). Bimodal-hybrid heterocyclic amine targeting oxidative pathways and copper mis-regulation in Alzheimer's disease. Metallomics 6, 2072–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs A. M., Agim Z. S., Mishra V. R., Tambe M. A., Director-Myska A. E., Turteltaub K. W., McCabe G. P., Rochet J. C., Cannon J. R. (2014). 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) is selectively toxic to primary dopaminergic neurons in vitro (vol 140, pg 179, 2014 ). Toxicol. Sci. 141, 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haining R. L., Jones T. M., Hernandez A. (2016). Saturation binding of nicotine to synthetic neuromelanin demonstrated by fluorescence spectroscopy. Neurochem. Res. 41, 3356–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban, R., Cheng, E., and Hebert, D. N. (2002). Coexpression of wild-type tyrosinase enhances maturation of temperature-sensitive tyrosinase mutants. J Invest Dermatol 119, 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday G., Lees A., Stern M. (2011). Milestones in Parkinson's disease—Clinical and pathologic features. Mov. Disord. 26, 1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harischandra D. S., Rokad D., Neal M. L., Ghaisas S., Manne S., Sarkar S., Panicker N., Zenitsky G., Jin H., Lewis M., et al. (2019). Manganese promotes the aggregation and prion-like cell-to-cell exosomal transmission of alpha-synuclein. Sci. Signal. 572, eaau4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T. (2010). Tyrosinase-expressing neuronal cell line as in vitro model of Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11, 1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T., Treis A., Patenge N., Fiesel F. C., Springer W., Kahle P. J. (2008). Parkin protects against tyrosinase-mediated dopamine neurotoxicity by suppressing stress-activated protein kinase pathways. J. Neurochem. 105, 1700–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haza A. I., Morales P. (2011). Effects of (+)catechin and (−)epicatechin on heterocyclic amines-induced oxidative DNA damage. J. Appl. Toxicol. 31, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M., Little M. D., Bankiewicz K., Yang S. C., Markey S. P., Johannessen J. N. (1991). Selective retention of MPP+ within the monoaminergic systems of the primate brain following MPTP administration: An in vivo autoradiographic study. Neuroscience 40, 133–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E., Graybiel A. M., Agid Y. A. (1988). Melanized dopaminergic-neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinsons-disease. Nature 334, 345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose H., Ozaki N., Nakahara D., Naoi M., Wakabayashi K., Sugimura T., Nagatsu T. (1988). Effects of heterocyclic amines in food on dopamine metabolism in nigro-striatal dopaminergic-neurons. Biochem. Pharmacol. 37, 3289–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S. (2006). Encapsulation of a reactive core in neuromelanin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14647–14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. (1998). Oxidative mechanisms in nigral cell death in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 13(Suppl. 1), 24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Sun Q., Chen S. (2016). Oxidative stress: A major pathogenesis and potential therapeutic target of antioxidative agents in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 147, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph N. M., He S., Quintana E., Kim Y. G., Nunez G., Morrison S. J. (2011). Enteric glia are multipotent in culture but primarily form glia in the adult rodent gut. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3398–3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju K. Y., Lee Y., Lee S., Park S. B., Lee J. K. (2011). Bioinspired polymerization of dopamine to generate melanin-like nanoparticles having an excellent free-radical-scavenging property. Biomacromolecules 12, 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim M. R., Wanibuchi H., Wei M., Morimura K., Salim E. I., Fukushima S. (2003). Enhancing risk of ethanol on MeIQx-induced rat hepatocarcinogenesis is accompanied with increased levels of cellular proliferation and oxidative stress. Cancer Lett. 192, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson O., Berg C., Brittebo E. B., Lindquist N. G. (2009). Retention of the cyanobacterial neurotoxin beta-N-methylamino-l-alanine in melanin and neuromelanin-containing cells—A possible link between Parkinson-dementia complex and pigmentary retinopathy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 22, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky A. R., Akhmedov N. G., Denisenko S. N., Denisko O. V. (2002). H-1 NMR spectroscopic characterization of solutions of Sepia melanin, Sepia melanin free acid and human hair melanin. Pigment Cell Res. 15, 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemali M., Gioffre D. (1985). Anatomical localisation of neuromelanin in the brains of the frog and tadpole. Ultrastructural comparison of neuromelanin with other melanins. J. Anat. 142, 73–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. T., Choi J. H., Chang J. W., Kim S. W., Hwang O. (2005). Immobilization stress causes increases in tetrahydrobiopterin, dopamine, and neuromelanin and oxidative damage in the nigrostriatal system. J. Neurochem. 95, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T., Naoi M., Wakabayashi K., Sugimura T., Nagatsu T. (1990). 3-Amino-1-methyl-5h-pyrido[4,3-B]indole (Trp-P-2) and other heterocyclic amines as inhibitors of mitochondrial monoamine oxidases Separated from human brain synaptosomes. Neurochem. Int. 16, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korytowski W., Sarna T., Zar ba M. (1995). Antioxidant action of neuromelanin: The mechanism of inhibitory effect on lipid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 319, 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn W., Müller T., Groβe H., Rommelspacher H. (1996). Elevated levels of harman and norharman in cerebrospinal fluid of parkinsonian patients. J. Neural Transm. 103, 1435–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langouet S., Paehler A., Welti D. H., Kerriguy N., Guillouzo A., Turesky R. J. (2002). Differential metabolism of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine in rat and human hepatocytes. Carcinogenesis 23, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston J. W., Forno L. S., Tetrud J., Reeves A. G., Kaplan J. A., Karluk D. (1999). Evidence of active nerve cell degeneration in the substantia nigra of humans years after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine exposure. Ann. Neurol. 46, 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawana V., Singh N., Sarkar S., Charli A., Jin H. J., Anantharam V., Kanthasamy A. G., Kanthasamy A. (2017). Involvement of c-Abl kinase in microglial activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and impairment in autolysosomal system. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 12, 624–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. W., Tapias V., Di Maio R., Greenamyre J. T., Cannon J. R. (2015). Behavioral, neurochemical, and pathologic alterations in bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic G2019S leucine-rich repeated kinase 2 rats. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 505–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell J. R., White A. R. (2018). Nexus between mitochondrial function, iron, copper and glutathione in Parkinson's disease. Neurochem. Int. 117, 126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist N. G., Larsson B. S., Lydén-Sokolowski A. (1988). Autoradiography of [C-14] paraquat or [C-14] diquat in frogs and mice—Accumulation in neuromelanin. Neurosci. Lett. 93, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Simon J. D. (2005). Metal-ion interactions and the structural organization of Sepia eumelanin. Pigment Cell Res. 18, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E. D., Michalec M., Jiang W., Factor-Litvak P., Zheng W. (2014). Elevated blood harmane (1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole) concentrations in Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology 40, 52–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann D. M. A., Yates P. O. (1983). Possible role of neuromelanin in the pathogenesis of Parkinsons-disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 21, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga J., Riley P. A., Solano F., Hearing V. J. (2002). Biosynthesis of neuromelanin and melanin: The potential involvement of macrophage inhibitory factor and dopachrome tautomerase as rescue enzymes. Catecholamine Res. 53, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda M., Botti D., Bonfigli A., Ventura T., Arcadi A. (1984). Tyrosinase-like activity in normal human substantia nigra. Gen. Pharmacol. 15, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]