Abstract

This study examined whether experimental functional analyses (FAs) conducted by parents at home with coaching via telehealth would produce differentiated results, and compared these results to the functions identified from structured descriptive assessments (SDAs) also conducted by parents at home via telehealth. Four boys between the ages of 4- and 8-years old with intellectual and developmental disabilities and their parents participated. All assessments were conducted in the children’s homes with their parents serving as intervention agents and with coaching from remote behavior therapists using videoconferencing technology. Parent-implemented FAs produced differentiated results for all 4 children in the study. Overall, analyzing antecedent-behavior (A-B) and behavior-consequence (B-C) relations from the SDA videos identified only half of the functions identified by the FAs. For children whose SDA results were differentiated, analyzing A-B relations correctly identified 4 of 5 functions. Analyzing B-C relations correctly identified 5 of 6 functions identified by the experimental FA, but overidentified attention for all children. Implications for conducting functional analyses and interpreting structured descriptive assessment via telehealth are discussed.

Keywords: functional assessment, functional analysis, telehealth, structured descriptive assessment, contingency space analysis

Parents of children with developmental disabilities who live in rural or remote locations may not have access to behavior analytic services for the treatment of their children’s challenging behavior. The absence of such services can lead to more restrictive school and residential placements (Bierman, Kalvin, & Heinrichs, 2015), increased peer rejection (Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003), and higher levels of parental stress (Baker et al., 2003).

Key to the successful treatment of children’s challenging behavior is the identification of its maintaining variables through a functional analysis (FA; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982). Since the publication of Iwata’s seminal article, hundreds of studies have reported the outcomes of FAs in different settings, with different populations, and for a variety of problem behaviors (e.g., Beavers, Iwata, & Lerman, 2013; Mueller, Nkosi, & Hine, 2011). Given such a large inductive database, FA has become the “gold standard” for designing individualized behavioral treatment programs.

Several meta-analyses have shown that matching treatment to the function of problem behavior can result in significantly better treatment outcomes than non-function-based treatment (Campbell, 2003; Miller & Lee, 2013). For example, Campbell reviewed 117 studies published from 1966 to 1998 involving treatment for three categories of problem behavior (internalizing, externalizing, combined) in 181 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In 32 of the studies, treatment was informed by a descriptive or experimental functional assessment, whereas in 85 of the studies it was not. Results of a 2 (functional assessment or not) by 3 (category of problem behavior) ANOVA on the percentage of zero data during treatment revealed a significant main effect for functional assessment and no interaction. These results indicated that a pretreatment functional assessment significantly improved treatment outcomes for all three categories of problem behavior.

One approach to conducting FAs with children of parents who live in remote locations is through teleconferencing using Internet connectivity and video camera technology, or what is referred to as telehealth. Several studies have shown that applied behavior analysts can help parents implement FAs and conduct functional communication training (FCT) effectively via telehealth (Lindgren et al., 2016; Suess, Wacker, Schwartz, Lustig, & Detrick, 2016; Wacker et al., 2013a, 2013b). For example, Wacker et al. (2013b) evaluated whether parents of children with ASD could conduct standard FA test conditions with coaching from remote behavioral consultants. Twenty children with ASD and their parents, who resided near regional clinics where the sessions took place, participated. In addition to coaching by a remote behavioral consultant, an on-site parent assistant trained in FA procedures accompanied each parent and provided support during each telehealth session. FAs conducted over an average of five, 1-hr sessions revealed a social function for the problem behavior of 18 of the 20 children assessed.

Lindgren et al. (2016) compared the behavioral outcomes of FA and FCT services delivered by behavioral consultants in vivo in parents’ homes, via telehealth in parents’ homes, or via telehealth in regional clinics. Parent-implemented FAs revealed more than one function for most children regardless of setting (home or regional clinic) or service delivery method (in vivo or telehealth), and FCT led to over 90% reductions in challenging behavior for children in all three groups. Suess et al. (2014) examined the integrity with which the first three of the 30 in-home telehealth participants in Lindgren et al. (2016) implemented FCT procedures. Suess et al. (2014) found that procedural integrity averaged 73%, 77%, and 80% for each of the parents during independent (not coached) FCT sessions.

To date, most studies evaluating the efficacy of FA and FCT services provided via telehealth have been conducted either at regional clinics with support from on-site parent assistants or in parents’ homes with support from on-site behavioral coaches (e.g., Wacker et al., 2013b). One exception here was the home telehealth group in Lindgren et al. (2016) for whom all FA and FCT sessions were conducted by parents in their homes with only remote behavioral coaching. FA results for this group identified significantly fewer attention functions and significantly more tangible functions than for the in vivo consultant group. Although Lindgren et al. (2016) provide preliminary support for the validity of FAs conducted entirely by parents at home via telehealth, replication is needed. Would FAs conducted by different parents in different settings also produce differentiated results? Is it typical for parent-implemented FAs to identify more than one function for children’s challenging behavior? Would a tangible function be identified in the majority of cases?

Although experimental FAs remain the gold standard for identifying behavioral function, descriptive functional assessment methods may be necessary when clinicians choose not to conduct experimental FAs or parents are reluctant to temporarily reinforce challenging behavior. For example, there is some evidence to suggest that clinicians may favor descriptive over experimental methods for identifying the function of problem behavior. In a survey of 682 certified behavior analysis practitioners, Oliver, Pratt, and Normand (2015) found that only 36.3% reported using experimental FAs always or almost always in their practice, whereas 93.6% reported using descriptive methods.

To date, research examining agreement between descriptive and experimental functional assessment methods has produced mixed results. For example, Martens, Gertz, Werder, and Rymanowski (2010) calculated the conditional probability of various teacher-delivered social consequences (e.g., attention, escape, tangible) given both the presence and absence of child problem behavior. They identified as potential reinforcers those consequences that occurred more often following problem behavior than its absence. This analytic approach based on behavior-consequence (B-C) recordings identified the same reinforcers as an experimental FA conducted by direct care providers for two of the three children in the study. Pence, Roscoe, Bourret, and Ahearn (2009) compared the results from various descriptive assessment methods involving the calculation of conditional probabilities to experimental FA outcomes for six children and youth with ASD. Although similar outcomes were obtained across the descriptive methods, the functions identified showed little agreement with the experimental FAs.

An alternative descriptive assessment method, structured descriptive assessment (SDA), focuses on the motivating operations for problem behavior. SDA involves measuring problem behavior under different antecedent contexts that are manipulated or “structured” by direct care providers in the natural environment. SDA results are traditionally reported as line graphs (Anderson & Long, 2002) or bar graphs (e.g., Simacek, Dimian, & McComas, 2017) showing the frequency, duration, or rate of problem behavior in each antecedent context (i.e., A-B relations). Anderson and Long (2002) compared the results of SDA to FA test conditions for four children with developmental disabilities. During SDAs, the children’s teacher or parent was instructed to withhold attention, restrict access to desired items, or present task demands during times when activities relevant to such manipulations typically occurred. Care providers manipulated the motivating operations with a high degree of fidelity during the SDA, and similar functions of problem behavior were identified by the two assessment procedures for three of the four children.

Recent research suggests that parents can be coached to conduct SDA sessions, as in Anderson and Long (2002), at home while connecting with researchers over a teleconsultation platform. Simacek et al. (2017) coached parents remotely via telehealth to conduct 5-min SDA sessions to identify contexts that evoked communicative responses, challenging behavior, or both topographies. For all three children, SDAs revealed higher levels of communicative responses in at least one context. These data were then used to design and FCT program for each of the three participants. Overall, the SDAs implemented at home by parents with coaching from researchers via telehealth informed efficacious interventions.

Although an FA was conducted with two of the three participants in the Simacek et al. (2017) study, the researchers did not directly compare SDA and FA results for those two participants. Moreover, previous studies examining descriptive B-C relations (e.g., Martens et al., 2010; Pence et al., 2009) have computed conditional probabilities based on unstructured observations rather than structured sessions like those in an SDA. Whether the analysis of B-C relations from SDA videos versus unstructured observations would more accurately identify behavioral function remains unknown. The goals of the present study therefore were twofold. First, we examined whether experimental FAs conducted entirely by parents at home with remote coaching via telehealth would produce differentiated results. Second, we compared two different ways of analyzing the data from SDAs also conducted at home via telehealth; one based on the mean percent intervals of problem behavior in each antecedent context (A-B relations) and the other based on the mean conditional probability of each consequence across contexts (B-C relations). The correspondence between these two analytic strategies and an experimental FA was evaluated by comparing their results.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were four boys between the ages of 4- and 8-years old. The children were referred by clinical providers for participation in a research project evaluating the utility of telehealth as a service delivery mechanism for addressing problem behavior of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who had limited communication skills. Procedures, including videoconferencing over Google Hangout, were approved by the University Human Research Protection Program/Institutional Review Board-Biomedical. Google Hangout (now Meet), when used in the University’s system, is HIPAA-compliant based on the Business Associates Agreement held between Google and the University. Study procedures were described during telephone conversations with parents before parents returned signed consent forms to the research team. The research team never met any of the families in person.

Leo was a 7-year-old Caucasian boy diagnosed with ASD and Lissencephaly. He lived with both parents. Leo’s functional analysis results were previously reported in Dimian, Elmquist, Reichle, and Simacek (2018) for use in teaching functional communication responses on a speech-generating device. He used gestures in the form of pointing and reaching to communicate and had no recognizable vocal language. He was unable to walk but crawled on his hands and used his hands and feet to “scoot” on his bottom on the floor; he used a wheelchair at school and in the community. Leo was dependent on others for all self-care routines and received nutrition via a gastrostomy-tube. Leo engaged in problem behavior in the form of crying and screaming, and his parent reported that this behavior occurred most frequently during transitions and daily care routines (e.g., hair brushing). Jay was an 8-year-old Caucasian boy diagnosed with Rett syndrome. Jay lived with both parents. He used gestures in the form of reaching and tapping on items and people to communicate and his vocal language was limited to single word approximations. Jay was able to walk, but occasionally walked on his toes. He could eat by mouth and feed himself. He was dependent on others for all self-care routines and engaged in repetitive hand movements at midline (e.g., clasping and hand clapping). Jay engaged in self-injurious behavior in the form of head hitting and head banging. Bill was a 7-year-old Caucasian boy diagnosed with ASD. Bill lived with both parents. He spoke in complete sentences and was able to walk and feed himself. He required assistance in the form of verbal reminders and prompts for all self-care routines. Bill engaged in problem behavior in the form of aggression, property destruction, and yelling. Kory was a 4-year-old Caucasian boy diagnosed with ASD. Kory lived with both parents. He spoke in 4–5 word sentences and was able to walk, feed himself, and complete self-care routines. Kory engaged in problem behavior in the form of aggression, yelling, and taking items from others’ hands.

All telehealth sessions were conducted in the children’s homes with their parents serving as interventionists, and researchers coaching parents remotely using videoconferencing technology. Researchers were located in a lab on the University campus and connected with families in their home using Google Hangouts. The researcher coached the parent to conduct the procedures in each SDA and FA condition. None of the parents reported any experience with functional analysis, FCT, or the use of Internet connection for telehealth consultation. Leo’s sessions were conducted on the floor of the living room with one parent present. Jay’s sessions were conducted in the living room of his home with one parent and occasionally a sibling present. Bill’s sessions were conducted in various rooms in his home, including the living room and his bedroom, with one parent and occasionally a sibling present. Kory’s sessions were conducted in the living room with one parent and occasionally a sibling present. The location of sessions was selected based on parent preference and a preassessment session in which the parent took the coach on a virtual tour (using the videocamera) of the preferred location and the coach made suggestions for location, angle, and lighting to ensure visibility during video conferences. During sessions, as the child moved around (e.g., from the chair to the floor or between two couches), the coach asked the parent to adjust the location or angle of the camera so that the child remained in the camera frame.

Behavioral Coaches

At the time the study was conducted, the behavioral coaches were doctoral students in the Special Education Program of the Educational Psychology Department at the University of Minnesota. One of the coaches was a board-certified behavior analyst and another had been a classroom teacher prior to enrolling in the program. All three coaches had completed coursework in functional assessment procedures and had conducted a number and variety of forms of functional assessments, both under the direction of faculty experts and independently (in vivo and via telehealth). Leo, Jay, and Bill’s coaches had coached several families to conduct functional assessments and interventions via telehealth, and Kory’s coach had observed the other researchers coach families via telehealth on several occasions prior to independently coaching the participant’s family in this study.

Materials—Videoconferencing Equipment

Internet-based, live videoconferencing was conducted over a high-speed Internet connection using the Google Hangouts Meet platform and a dedicated e-mail address for use only with the researchers to communicate via e-mail and connect to Google Hangouts Meet. Researchers used a dedicated computer (Dell OptiPlex 3010 Desktop) with a Dell 24” monitor. Researchers used a Logitech HD Pro Webcam C920 on a Polaroid 8” Heavy Duty Mini Tripod to capture their image for the family to see and Logitech ClearChat Comfort/USB Headset H390 to capture sound (i.e., researcher talking) and for the researcher to hear the family. All sessions were video recorded using Debut Video Capture software and all data, including videos, were stored on the University’s secure encrypted server. All families had preexisting high-speed Internet service to their home. Researchers loaned an ASUS Chromebook C200M with built-in microphone, Logitech HD Pro Webcam C920, and a Polaroid 8” Heavy Duty Mini Tripod to each family for use during the project to communicate remotely via videoconferencing with research staff. Three of the parents used the speaker and microphone on their laptop to communicate with the behavioral coaches. Kory was reactive to the coach’s comments (i.e., didn’t show problem behavior in their presence), so his mother wore a Bluetooth earpiece that she owned prior to the start of the study.

Response Definitions and Measurement

Child behavior categories.

Each child’s target problem behaviors were coded under a single category using 10-s partial interval recording. Leo’s target behavior was crying and/or screaming, which was defined as engaging in vocalizations louder than a conversational level accompanied by tears and/or a grimace that lasted longer than 2 s. Jay’s target behaviors included head hitting and head banging. Head hitting was defined as moving his arm and hand toward his head or face and making or attempting contact with his head or face with an open or closed hand. Head banging was defined as hitting his head against a surface or item by moving his head in a forward motion and then back again, contacting the object more than once. Bill’s target behaviors included aggression, property destruction, and yelling, crying, or screaming. Aggression was defined as attempting, within two inches of any location on another person’s body, to bite, pull or grab hair, hit, kick, throw items toward another person, or forcefully grab items from his parents or sibling. Property destruction was defined as throwing, ripping, kicking, crumbling, pushing over, knocking off a surface, or breaking an object. Yelling, crying, or screaming were defined as engaging in vocalizations above a conversational tone. Kory’s target behaviors included grabbing, yelling, and aggression. Grabbing was defined as reaching for or taking an object that another person was holding, excluding when the person gave Kory permission or passed the object to him (i.e., was moving the object in his direction when he reached for it). Yelling was defined as engaging in a guttural/uh/sound. Aggression included hitting and kicking, defined as raising his hand or foot then bringing it quickly into contact with an object or person.

Parent behavior categories.

Parents’ responses to their children’s behavior were also coded each session and included attention, access to tangibles, escape, or no consequence. Attention was defined as directing any verbal statement to the child, making physical contact with the child, and/or directing nonverbal facial expressions or gestures toward the child. Access to tangibles was defined as providing the child with an item or allowing continued access to an item. Escape occurred after the parent placed a demand on their child, the child did not complete the task, and compliance was not prompted or guided. Demands were only used in the scoring of escape and were not included under the attention category. Escape was scored in consecutive intervals until the child completed the demand or another demand was placed on the child. No consequence was defined as the parent NOT providing their child with attention or access to tangibles or placing demands (e.g., interacting with another child or parent, interacting with the behavioral coach).

Data coding procedures.

For the SDAs and FAs, we coded child and parent behavior from video-recorded sessions. For the CSAs, we coded the presence or absence of child problem behavior as well as parent responses to child behavior using 10-s partial interval recording. During each interval, CSA data were coded in three steps. First, at the beginning of each signaled interval, observers coded the absence of problem behavior by placing an O in the child behavior column. Second, if by the end of the interval problem behavior still had not occurred, any parent responses to the child’s other behavior during that same interval were scored using partial-interval recording (i.e., occurrence or nonoccurrence of each parent response in that interval). Third, if child problem behavior occurred at any point during the interval, observers placed a slash through the O and recorded any parent responses only to the child’s problem behavior also using partial-interval recording. For the FAs, we coded the occurrence of child and parent behavior using 10-s partial-interval recording. We used partial interval recording during the FAs because some problem behaviors (e.g., crying, screaming) had meaningful durations and would not be accurately captured with frequency counts.

Procedures and Experimental Design

Study phases.

With each participant, we conducted an SDA to identify contexts in which problem behavior was likely to occur and to generate a direct observation based hypothesis regarding the function of the problem behavior. Then we conducted an FA to test the effects of specific consequences on problem behavior. For the purposes of this investigation, researchers coded SDA videos and plotted the occurrence of problem behavior in each context, coded and plotted CSAs based on a sample of SDA videos, and coded FA videos. Functional communication training was conducted following the FA for each participant, however intervention is beyond the scope of this paper, therefore these data are not presented.

Structured descriptive assessments (SDAs).

The goal of the SDAs was to identify those contexts associated with the highest levels of problem behavior. Toward this goal, we computed the percentage of intervals with problem behavior for each video and then averaged these percentages across all videos in which the same motivating operation was manipulated. For each SDA, we instructed the parent to arrange contexts to reflect situations that the child was likely to encounter at home. These contexts included (a) diverted attention (DA) in which the child played alone while the parent paid attention to something or someone else, (b) restricted access (RA) in which the parent restricted the child’s access to a preferred toy/activity (i.e., preferred TV program), (c) demand (DE) in which the parent placed demands on the child (e.g., directions to clean up or brush hair), and (d) free play (FP) in which the child was permitted to engage with preferred items/activities, could access attention, and no demands were imposed. Parents were instructed to implement antecedents (e.g., parents stating “all done toys”) related to the contexts and were instructed to respond as they typically would to their child during the SDA sessions. In the two attempted RA conditions for Bill, parents verbally told him he was “all done” with the preferred activities (playing with a sensory bin and viewing a tablet). His parents did not remove the items from him, although they continued to verbally tell him “the timer is all done,” and so forth. As coaches had instructed parents to “respond how they typically would,” the coaches did not instruct the parents to continue to make physical attempts to remove the items from him.

For each context, the behavioral coach provided instructions similar to the following: “Let’s see what happens when you tell him it is time to clean up. Do clean-up time the way you normally would and respond the way you usually do when he is either compliant or engages in problem behavior.” In about a third of the videos (36%) across all contexts, behavioral coaches gave additional prompts (range 1–4, median and mode of 1) for parents to manipulate motivating operations beyond this initial instruction. The behavioral coaches did not instruct the parents to manipulate any consequences during the SDA sessions.

Contingency space analyses (CSAs).

We coded all available videos for each child, but only included those in which problem behavior occurred in the CSAs (including FP contexts). First, we calculated the conditional probability of each consequence given the presence and absence of problem behavior and averaged these values across videos. We then plotted the joint conditional probabilities for each consequence in coordinate space, with the y-axis depicting the likelihood of consequences for problem behavior and the x-axis depicting the likelihood of consequences for the absence of problem behavior. Those consequences that followed problem behavior on at least a partial schedule (conditional probabilities of .40 or higher) were identified as potential reinforcers.

Functional analyses (FAs).

The goal of the FAs was to isolate and manipulate consequences and test their effect on the target problem behavior. The coaches explained the procedures for each condition to the parent and told the parent that they could terminate the session at any time if behavior became too severe. No FA sessions were terminated. During each session, the coach prompted the parent to arrange the motivating operation (i.e., say, “It is my turn” and remove the toy) and to deliver the relevant consequence contingent on the problem behavior. Three conditions were conducted with Kory and four conditions were conducted with the other three participants. For all four participants, a free-play condition was conducted in which the child played with his preferred toys or watched a preferred program on TV and had access to parent attention with no task demands. There were no consequences programmed for problem behavior. The behavioral coach instructed the parent to make preferred activities and attention available regardless of his behavior, and to avoid presenting demands. For all participants, positive reinforcement in the form of access to attention and access to preferred activities were tested in two separate conditions. In the attention condition, the behavioral coach instructed the parent to either attend to a sibling in the same general area or to read, complete some work, or answer messages on their phone. The behavioral coach instructed the parent to provide attention to their son for 20 s only following problem behavior. In the tangible condition, the behavioral coach instructed the parent to play with their son with their preferred activities for approximately 1 min. Next, the behavioral coach instructed the parent to say something like, “My turn to play with that” and to remove the preferred activity. The behavioral coach instructed the parent to return the preferred item to the child contingent on problem behavior and then to repeat “My turn to play with that” and remove the preferred activity again after approximately 20 sec. Finally, negative reinforcement in the form of escape from nonpreferred tasks such as hair brushing (Leo), hitting a drum with an open hand (Jay), and toy clean-up and homework (Bill) was tested. Escape was not included in Kory’s FA because his mother reported no difficulty related to compliance with demands, and no problem behavior was observed in the demand condition in the SDA. For the other participants, the behavioral coach instructed the parent to direct their son to do the task and if problem behavior occurred, to pause the task and say something like, “Ok, we can wait a minute” for approximately 20 s before redelivering a prompt to do the task. A pattern of elevated problem behavior across sessions of one or more of the positive or negative reinforcement conditions suggested the problem behavior was reinforced by the consequence delivered in that condition.

Videotape Scoring

Data on child and adult behavior were coded by graduate students and university faculty (the SDA data, Syracuse University; the FA data, the University of Minnesota) with extensive experience coding direct observation data. In addition, undergraduate students were trained to code randomly selected videos of FA sessions for the purpose of assessing interobserver agreement and procedural integrity. Scorers were equipped with recording sheets, a pencil, a computer with Internet access and sound, and access to the SDA and FA videos of participants via a secure encrypted server. The number of SDA videos, the number of FA sessions that were conducted, the length of sessions, and the number of days over which they were conducted for each child are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Assessment Duration by Participant

| Child | SDA | FA |

|---|---|---|

| Leo | 9 sessions | 12 sessions |

| 4 days | 2 days | |

| 3–5 min each | 3 min each | |

| Jay | 14 sessions | 28 sessions |

| 4 days | 7 days | |

| 5 min each | 5 min each | |

| Bill | 9 sessions | 15 sessions |

| 4 days | 3 days | |

| 3–5 min each | 3 min each | |

| Kory | 10 sessions | 8 sessions |

| 3 days | 2 days | |

| 5 min each | 5 min each |

Note. SDA = structured descriptive assessment; FA = functional analysis.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Integrity

A second person scored the SDA video clips for 57% of sessions across all participants and contexts. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements (i.e., agreement that a target behavior or consequence occurred or did not occur within a 10-s interval) by agreements plus disagreements (i.e., disagreement that a target behavior or consequence occurred or did not occur within a 10-s interval) and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean (range) interobserver agreement for occurrence/nonoccurrence of target behaviors was 94.4% (83.3–100%), 99.3% (96.7–100%), 99.1% (96.6–100%), and 94% (90–100%) for Leo, Jay, Bill, and Kory, respectively. Mean (range) interobserver agreement for occurrence or nonoccurrence of each consequence was 93.0 (68–100%) for attention, 99.0 (88.9–100%) for escape, 92.6 (53–100%) for tangible, and 94.7 (73–100%) for no consequence. A second scorer coded the FA videotapes for 42%, 36%, 60%, and 50% for Leo, Jay, Bill, and Kory, respectively. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements (i.e., agreement that a target behavior or consequence occurred or did not occur within a 10-s interval) by agreements plus disagreements (i.e., disagreement that a target behavior or consequence occurred or did not occur within a 10-s interval) and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean (range) interobserver agreement for occurrence/nonoccurrence of target behaviors across conditions was 96% (78–100%), 100%, 91% (77–100%), and 95% (75–100%) for Leo, Jay, Bill, and Kory, respectively.

Parents’ procedural integrity, or compliance with the behavioral coach’s instructions about how to interact with their child, was scored during 100% of SDA sessions for each participant. For each session, parents were provided instructions either immediately before or within 30 s of the start of session. For the SDA, the percentage of opportunities in which each child’s parents complied within 5 s of a coach’s instruction was calculated. Leo and Jay’s parents complied with 100% of instructions provided by the behavioral coach, whereas Bill and Kory’s parents complied with 80% and 92% of instructions provided by the behavioral coach, respectively. Procedural integrity was scored for 100%, 36%, 67%, and 100% of the FA sessions for Leo, Jay, Bill, and Kory, respectively. Mean procedural integrity across FA conditions was 98% (r = 78–100%), 99% (r = 92–100%), 94% (r = 50–100%), and 94% (r = 63–100%) for Leo, Jay, Bill, and Kory, respectively. Failures of procedural integrity were observed in each condition, perhaps most notably in free-play sessions where occasionally a preferred activity was unavailable (e.g., parent could not find preferred video) or the parent delivered instructions (e.g., “push this button to make it go”).

Parent Acceptability of Procedures

After the final intervention session was conducted with a participant, the parent completed the Treatment Acceptability Rating Form-Revised (TARF-R; Reimers, Wacker, & Cooper, 1991). The TARF-R is a 7-point Likerttype rating scale that consists of 20 items. Higher ratings indicate greater acceptability.

Results

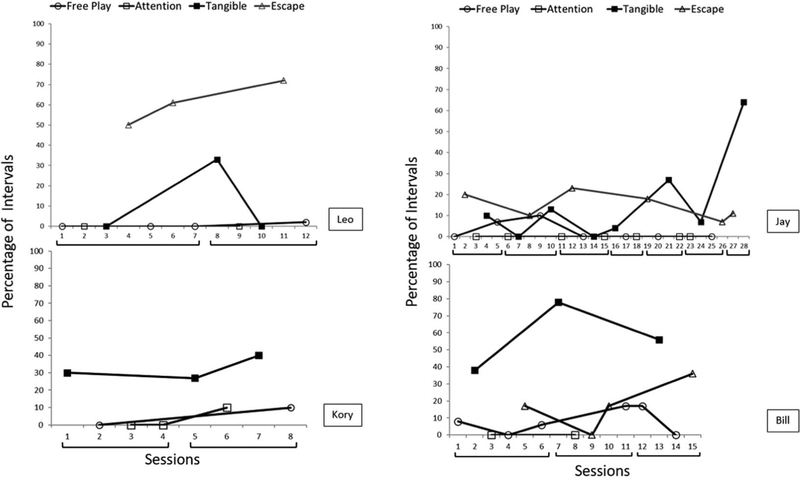

Results of each child’s FA are shown in Figure 1. Results were clearly differentiated for Leo and Kory, who showed higher levels of problem behavior during the escape (Leo) and tangible (Kory) conditions. Although Jay’s FA results were less differentiated, he showed higher levels of problem behavior during the escape and tangible conditions, with the last tangible data point showing clear differentiation. Jay’s results suggested possible tangible and escape functions. Results for Bill suggested a clear tangible function and a possible escape function with smaller increases observed during the escape condition. Kory, Jay, and Bill all exhibited at least occasional problem behavior during the FP condition.

Figure 1.

Results of the functional analysis for each child. Brackets under the abscissa scale in each panel show those sessions that occurred on the same day. This figure is used with permission.

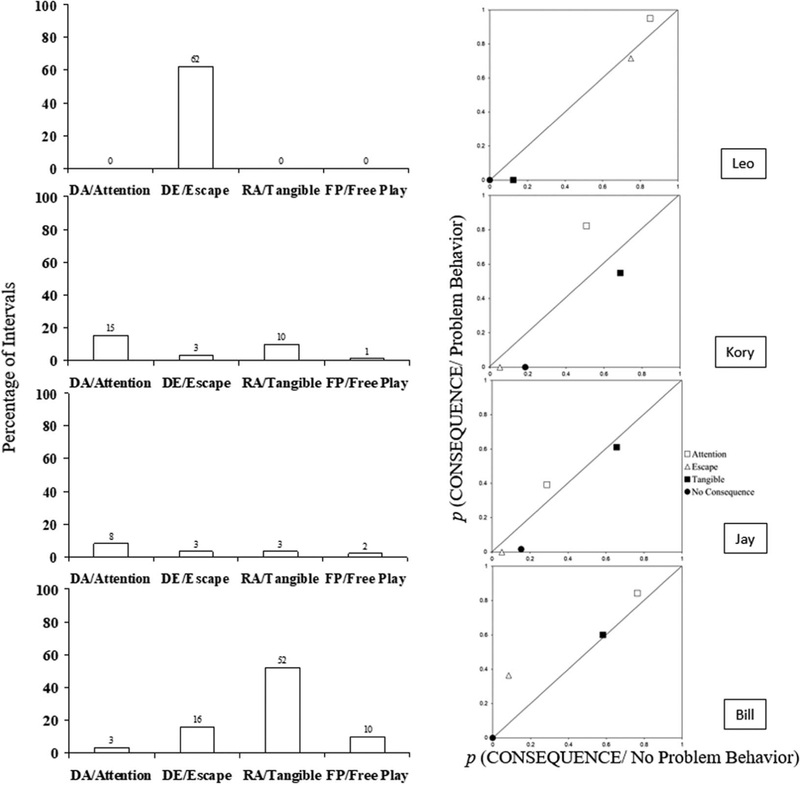

Results of the two approaches for analyzing the SDA results are shown in Figure 2. As shown in the left side of Figure 2 (A-B relations), Leo exhibited problem behavior only in the DE/Escape context (62% of intervals). Kory showed higher mean levels of problem behavior in the DA/Attention (15%) and RA/Tangible (10%) contexts, whereas Jay’s mean levels of problem behavior were low and undifferentiated across all SDA contexts. Bill showed the highest mean levels of problem behavior in the RA/Tangible context (52%) followed by the DE/Escape context (16%). Overall, coaching parents to manipulate only the motivating operations for their children’s problem behavior but to respond as usual led to lower levels of problem behavior but produced differentiated results for three of the four children. These results suggested an escape function for Leo’s problem behavior, attention and tangible functions for Kory’s problem behavior, tangible and escape functions for Bill’s problem behavior, and were undifferentiated for Jay.

Figure 2.

Mean percent intervals of problem behavior in each context (left side; DA = diverted attention, DE = demand, RA = restricted access, FP = free play) and mean conditional probability of each consequence across contexts (ride side).

Results from the analysis of B-C relations are shown on the right side of Figure 2. Parent-delivered social consequences tended to fall naturally into two categories for each child; those that followed problem behavior on a partial schedule (range = .36 to .95) and those that never followed problem behavior. Rather than adopt an arbitrary cut score, we identified as potential functions any consequences that followed problem behavior on at least a partial schedule. With the exception of attention for Kory and escape for Bill, parents’ social consequences followed problem behavior or its absence about equally (i.e., fell near the diagonal in each plot). The analysis of B-C relations suggested attention and escape functions for Leo, attention and tangible functions for Kory, attention and tangible functions for Jay, and attention, tangible, and escape functions for Bill.

Table 2 provides a summary of the functions identified by the experimental FAs as well as each approach for analyzing the SDA data. Entries in the table show the number of children whose results were differentiated for each method, agreements of each analytic approach with the FA results, false positive (Type I) errors (i.e., identifying a function that was NOT found by the FA), and false negative (Type II) errors (i.e., failing to identify a function that WAS found by the FA). Shown at the bottom of the table are three percentage agreement indices. The first index, total agreement, was calculated as agreements over agreements plus false positive and false negative errors for all four children. To evaluate the accuracy of SDAs that produced differentiated results, we calculated a second percentage agreement index for all children except Jay. Finally, because the analysis of B-C relations overidentified attention as a function in all cases, we calculated a third percentage agreement index for all four children but omitted attention as a function.

Table 2.

Functions Identified by Each Assessment Procedure

| Procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | FA | A-B (% Intervals) | B-C (p/C) |

| Leo | Escape | EscapeA | EscapeA |

| Attention+ | |||

| Kory | Tangible | TangibleA | TangibleA |

| Attention+ | Attention+ | ||

| Jay | Escape | (Escape−) | (Escape−) |

| Tangible | (Tangible−) | TangibleA | |

| Attention+ | |||

| Bill | Tangible | TangibleA | TangibleA |

| Escape | EscapeA | EscapeA | |

| Attention+ | |||

| Differentiated | 4 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 4 (100%) |

| Agreements | 4 | 5 | |

| False negatives | 2 (Jay) | 1 (Jay) | |

| False positives | 1 (Attention) | 4 (Attention) | |

| Total agreement | 57% | 50% | |

| Total agreement (excluding Jay) | 80% | — | |

| Total Agreement (excluding attention) | — | 83% | |

Note. Functions with a superscript A indicate agreements, functions in parentheses with a superscript (−) indicate false negatives, and functions with a superscript (+) indicate false positives (FA = functional analysis; A-B = antecedent-behavior; B-C = behavior-consequence; % intervals = percent intervals of problem behavior; p/C = conditional probability of each consequence).

Overall, analyzing A-B relations (percentage of problem behavior in each context) and B-C relations (conditional probabilities of each consequence) from the SDA videos identified only about half of the functions identified by the experimental FA. For children whose SDA results were differentiated (i.e., excluding Jay), A-B relations correctly identified all four functions with one false positive error (80% total agreement). Excluding attention that was overidentified as a function for all four children, analyzing B-C relations identified 83% of the functions identified by the experimental FA even when the SDA results were undifferentiated (i.e., including Jay). With regard to parent acceptability of the procedures, across the four participating families, the average acceptability rating was 5.9 (range = 4–7). This level of acceptability is consistent with acceptability of FA and FCT procedures conducted in clinics and in homes via telehealth (see Lindgren et al., 2016).

Discussion

The goals of this study were (a) to examine if experimental FAs conducted by parents at home with remote behavioral coaching via telehealth would produce differentiated results, and (b) to evaluate the correspondence between two approaches for analyzing videos of parent implemented SDAs and the results of an experimental FA. When parents were coached to manipulate both the motivating operations and social reinforcers for problem behavior (i.e., conduct an FA), differentiated results were obtained for all four children. These findings extend previous research by Wacker et al. (2013b) and Suess et al. (2016) by demonstrating that the function(s) of children’s problem behavior can be identified when parents conduct FAs at home with no assistants present but with remote coaching from behavioral consultants.

When parents were coached to structure only the motivating operations for their children’s problem behavior but to respond as usual (i.e., conduct an SDA), we saw somewhat lower levels of problem behavior. In addition, all parent-delivered consequences fell close to the unity diagonal in the CSA plots (except for attention by Kory’s mother, which favored problem behavior), and attention was provided nearly continuously to three of the four children. These data indicate that when the parents “responded as usual” to their children’s behavior, they provided considerable amounts of attention and responded to both problem and appropriate behavior on similar intermittent schedules.

Overall, the analysis of A-B relations (percent intervals of problem behavior) and B-C relations (conditional probabilities of parent-delivered consequences) from video-recorded SDA sessions were consistent with only 57% and 50% of the functions identified by the experimental FAs, respectively. With that said, there did appear to be two conditions under which the descriptive analyses were accurate. First, results of the SDAs were differentiated for three of the four children. For the three children with differentiated SDA results, those contexts with the highest mean levels of problem behavior (i.e., A-B relations) agreed with 4/5 (80%) of the functions identified by the experimental FAs with one false positive error for attention. Second, analyzing the conditional probabilities of parent-delivered consequences (i.e., B-C relations) falsely identified attention as a function for all four children (i.e., four false positive errors). Excluding attention as a function, results of this approach agreed with 5/6 (83%) of the functions identified by the FAs even when the SDAs were undifferentiated.

Despite the overall low levels of agreement between the SDAs and experimental FAs, these findings may be of some clinical utility. Specifically, when the results of SDAs conducted by parents at home via telehealth are differentiated, our data suggest that they are likely to agree with the functions identified by an experimental FA. However, when SDA results are undifferentiated, analyzing the conditional probabilities of parent-delivered consequences from these same videos can accurately identify escape and tangible functions. In situations where parents are interacting one-on-one with their children, CSA data are likely to suggest an attention function in all cases even when attention is not indicated by an experimental FA.

It is not surprising that our analysis of parent-delivered social consequences overidentified attention as a function for all children. All SDA contexts required parents to interact individually with their child. The category of “no consequence” was scored infrequently, and parents provided frequent attention to their children for both appropriate and inappropriate behavior. Previous research has shown that descriptive B-C analyses tend to overidentify attention as a function due to its near continuous delivery (e.g., St. Peter et al., 2005; Thompson & Iwata, 2007), and this also appears to be a problem when parents are video-recorded interacting one-on-one with their children. With respect to the false negative errors involving escape for Jay, his SDA results were low and undifferentiated across contexts. Our data also suggest that parents complied with the vast majority of behavioral coaches’ instructions. Nonetheless, they manipulated motivating operations less than two times on average in each 3- or 5-min session, which may account in part for the generally low levels of problem behavior. In addition, we only had one video of the DE/Escape context for Jay, and he always complied with parent requests. As such, neither the A-B or B-C analyses could identify escape as a function even though Jay engaged in higher levels of problem behavior during this condition of the FA.

The ability to conduct FAs and SDAs entirely via telehealth is limited to those families with high-speed Internet service to their homes. This level of connectivity may not be available in some rural areas. The results of our analytic approaches are limited by the differing number of SDA videos, their sequencing across children, and the need for multiple videos in which at least some problem behavior was observed. Relatedly, our definitions of problem behavior included multiple topographies for Bill and Kory (e.g., aggression, property destruction, yelling). It is possible that each topography had a different function, but the results of Bill and Kory’s FAs do not support a hypothesis of different functions for different topographies. Parents also manipulated motivating operations at relatively low rates in all SDA contexts. Whether our B-C analysis would produce similar results when applied to naturally occurring parent–child interactions instead of SDAs is unknown, although findings by Pence et al. (2009) suggest this may not be the case. Future researchers might also compare the identification accuracy of scoring differing numbers of videos, and examine alternative or more directive strategies for instructing parents to manipulate motivating operations at higher rates during SDA sessions (e.g., setting a target for each session). Given the generally low base rates of problem behavior, we identified as potential functions any consequences that followed problem behavior on at least a partial schedule (i.e., with conditional probabilities of approximately .40 or higher). Adopting a higher cut score would obviously affect the accuracy of our B-C analyses. Finally, we were surprised to see problem behavior in the free play condition of the FAs for three of the four children.

Parents were successful in conducting FA test conditions at home with remote behavioral coaching, and the results were differentiated (i.e., identified a function of problem behavior) for all children in our study. When asked to manipulate motivating operations during brief SDA sessions, all parents complied with the vast majority of coach’s instructions. Examining the percent intervals of problem behavior in each SDA context was only accurate at identifying behavioral function when the SDA results were differentiated. Examining the conditional probabilities of each parent-delivered social consequence in these SDA contexts was only accurate at identifying escape and tangible functions but not attention which all parents delivered frequently, regardless of the occurrence of problem behavior. These findings suggest that the function of children’s problem behavior can be identified when parents are coached via telehealth to conduct experimental FAs at home without additional aides or assistants present. When it is not possible or desirable to conduct experimental FAs, our findings suggest that differentiated results of brief SDAs conducted by parents at home via telehealth may accurately identify the function of their children’s problem behavior. When SDA results are undifferentiated, analyzing the conditional probabilities of parent-delivered consequences (i.e., CSA) may help to accurately identify escape and tangible functions.

References

- Anderson CM, & Long ES (2002). Use of a structured descriptive assessment methodology to identify variables affecting problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35, 137–154. 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, & Low C (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47, 217–230. 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00484.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavers GA, Iwata BA, & Lerman DC (2013). Thirty years of research on the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 1–21. 10.1002/jaba.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Kalvin CB, & Heinrichs BS (2015). Early childhood precursors and adolescent sequelae of grade school peer rejection and victimization. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 367–379. 10.1080/15374416.2013.873983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM (2003). Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 24, 120–138. 10.1016/S0891-4222(03)00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimian AF, Elmquist M, Reichle J, & Simacek J (2018). Teaching communicative responses with a speech-generating device via telehealth coaching. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2, 86–99. 10.1007/s41252-018-0055-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, & Richman GS (1982). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20. 10.1016/0270-4684(82)90003-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, & Troop-Gordon W (2003). The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development, 74, 1344–1367. 10.1111/1467-8624.00611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren S, Wacker D, Suess A, Schieltz K, Pelzel K, Kopelman T, … Waldron D (2016). Telehealth and autism: Treating challenging behavior at lower cost. Pediatrics, 137 (Suppl. 2), S167–S175. 10.1542/peds.2015-2851O [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens BK, Gertz LE, Werder C. S. d-L., & Rymanowski JL (2010). Agreement between descriptive and experimental analyses of behavior under naturalistic test conditions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 19, 205–221. 10.1007/s10864-010-9110-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FG, & Lee DL (2013). Do functional behavioral assessments improve intervention effectiveness for students diagnosed with ADHD? A single-subject meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22, 253–282. 10.1007/s10864-013-9174-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MM, Nkosi A, & Hine JF (2011). Functional analysis in public schools: A summary of 90 functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 807–818. 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver AC, Pratt LA, & Normand MP (2015). A survey of functional behavior assessment methods used by behavior analysts in practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48, 817–829. 10.1002/jaba.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence ST, Roscoe EM, Bourret JC, & Ahearn WH (2009). Relative contributions of three descriptive methods: Implications for behavioral assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 425–446. 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, Wacker DP, & Cooper LJ (1991). Evaluation of the acceptability of treatments for children’s behavioral difficulties. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 13, 53–71. 10.1300/J019v13n02_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simacek J, Dimian AF, & McComas JJ (2017). Communication intervention for young children with severe neurodevelopmental disabilities via telehealth. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 744–767. 10.1007/s10803-016-3006-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter CC, Vollmer TR, Bourret JC, Borrero CSW, Sloman KN, & Rapp JT (2005). On the role of attention in naturally occurring matching relations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38, 429–443. 10.1901/jaba.2005.172-04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suess AN, Romani PW, Wacker DP, Dyson SM, Kuhle JL, Lee JF, … Waldron DB (2014). Evaluating the treatment fidelity of parents who conduct in-home functional communication training with coaching via telehealth. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23, 34–59. 10.1007/s10864-013-9183-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suess AN, Wacker DP, Schwartz JE, Lustig N, & Detrick J (2016). Preliminary evidence on the use of telehealth in an outpatient behavior clinic. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49, 686–692. 10.1002/jaba.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, & Iwata BA (2007). A comparison of outcomes from descriptive and functional analyses of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 333–338. 10.1901/jaba.2007.56-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker DP, Lee JF, Dalmau YCP, Kopelman TG, Lindgren SD, Kuhle J, … Waldron DB (2013a). Conducting functional communication training via telehealth to reduce the problem behavior of young children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25, 35–48. 10.1007/s10882-012-9314-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker DP, Lee JF, Dalmau YCP, Kopelman TG, Lindgren SD, Kuhle J, … Waldron DB (2013b). Conducting functional analyses of problem behavior via telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 31–46. 10.1002/jaba.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]