Abstract

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), a potent class of anticancer therapeutics, comprise a high-affinity antibody (Ab) and cytotoxic payload coupled via a suitable linker for selective tumor cell killing. In the initial phase of their development, two ADCs, Mylotarg®, and Adcetris® were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating hematological cancer, but the real breakthrough came with the discovery of the breast cancer-targeting ADC, Kadcyla®. With advances in bioengineering, linker chemistry, and potent cytotoxic payload, ADC technology has become a more powerful tool for targeted cancer therapy. In addition, ADCs with improved safety using humanized Abs with a unified ‘drug:antibody ratio’ (DAR) have been achieved. Concomitantly, there has been a significant increase in the number of clinical trials with anticancer ADCs with high translation potential.

Keywords: antibody drug conjugates, targeted cancer therapy, receptor mediated endocytosis, receptor overexpression, antibody bioengineering, advance linker, protein scaffold, Mylotarg, Adcetris, Kadcyla

Introduction

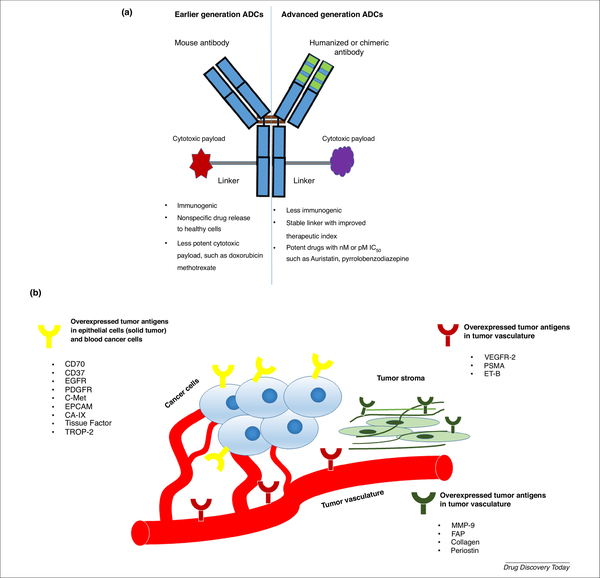

ADCs are an emerging class of targeted anticancer drug delivery agent that confer selective and sustained cytotoxic drug delivery to tumors [1]. An ADC can be divided into three main structural units (Figure 1a): the Ab; the cytotoxic agent; and the linker. Selecting a high-affinity Ab, stable linker, and potent cytotoxic payload enables the novel development of safe and efficient ADCs [2]. Many monoclonal Ab (mAb), such as avastin, rituximab, and cetuximab, are well known as standard treatments for solid tumors and hematological cancers [3]. By contrast, pristine chemodrugs, such as vinblastine, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel, have limited use for cancer treatment because of their nonspecific toxicity, thus narrowing the therapeutic window and increasing drug resistance [4,5]. Discovery of ADCs bridged the gap between the Ab and cytotoxic drug, creating highly specific anticancer agents with an improved therapeutic window [6]. The first FDA-approved ADC, Mylotarg®, a conjugate of the CD33 Ab and a calicheamicin payload, was developed for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), although this was withdrawn from the market 10 years after its initial approval. Adcetris®, a conjugate of the CD30 Ab and monomethyl auristatin E, was approved for the treatment of lymphoma [2]. In 2013, Kadcyla® was commercialized for targeting HER-2-positive metastatic breast cancer, with emtansine (DM1) as the cytotoxic agent [1]. Although ADCs are designed against tumor-specific antigens, there are challenges associated with Ab immunogenicity, antigen expression, premature drug release, and low chemotherapeutic drug potency [7]. However, over time, advances in bioengineering have improved the safety profile of ADCs, particularly third-generation ADCs. In this review, we discuss current prospects for, and technical improvements in, ADCs towards developing safer and more efficacious personalized cancer medicine.

Figure 1.

(a) Structural characteristics of earlier generation and advanced-generation antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) [75]. (b) List of targetable tumor antigens: epidermal growth factor receptor (EFGF), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR); tyrosine-protein kinase met (C-Met); epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM); carbonic anhydrase- IX (CA-9); tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 (TROP-2); vascular endothelial growth factors receptor-2 (VEGFR-2); prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA); endothelin receptor-B (ET-B); matrix metallopeptidase-9 (MMP-9); and fibroblast activated protein (FAP) [1].

Criteria for a successful ADC

Selection of targeting antigen

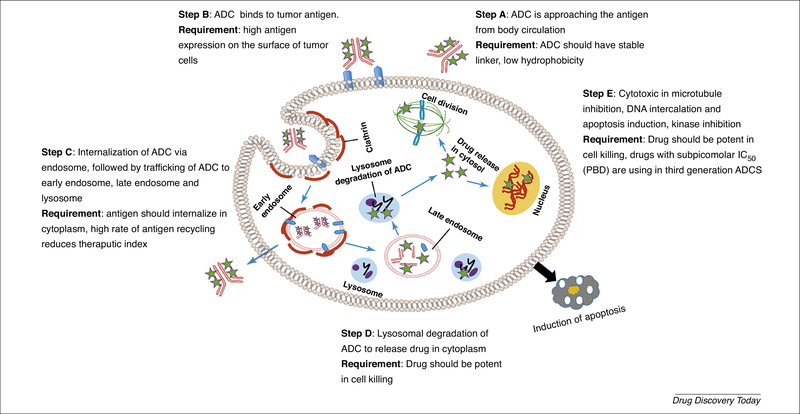

The selection of the targeting antigen the first and most important determining factor for a successful ADC. The ideal characteristics of a useful antigen are: (i) higher-fold expression in the tumor than in the healthy tissue; for example, Adcetris® targets the CD30 antigen, whose expression on the surface of mature and immature myeloid cells is high (90%–100%) in all patients with AML [8], whereas Kadcyla® targets the HER2 receptor, whose expression is almost 100-fold higher in cancer cells than in healthy cells [1]; (ii) internalization of antigen via endocytosis in the presence of ligand and its recycling back to the plasma membrane [9]; and (iii) homogeneous antigen expression in the tumor microenvironment and low antigen abundance in circulation [10] (Figure 1b). Therefore, given that ADCs target tumor-associated antigens, there should be minimum expression of such antigens on healthy cells to reduce any adverse effects [11]. For example, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is expressed on the surface of cancer cells, whereas, in the healthy prostate, it is found in the cytoplasm; therefore, noncancer cells are not affected by PSMA-targeting ADCs. Thus, the indium (In111)-labeled PSMA-targeting Ab, ProstaScint® can be clinically used for the early detection of prostate cancer [12]. It is suggested that 10 000 antigens per cell is the minimum number of antigens required to ensure the selective delivery of lethal cytotoxic drugs to cancer cells [2]. A major challenge to solid tumor therapy arises from antigen expression, which varies with tumor volume, heterogeneity, and treatment [13]. In addition to specific and sufficient expression, an optimal targeting antigen should also stimulate effective ADC internalization [14]. This internalization efficiency depends on the choice of Ab, epitopes of the antigen, and type of target (Figure 2). It has been reported that some targets frequently internalize regardless of ligand binding, whereas others reside permanently on the cell surface [2] (Figure 2). It was thought that the anticancer efficacy of ADCs relies on their internalization by cancer cells. However, recent work on spliced domain fibronectin-conjugated maytansinoid (SIP-F8-SS-DM1) showed that the internalization of antigen is not always necessary to achieve a therapeutic effect [15]. This is because this disulfide-linked ADC is reduced at the subendothelial extracellular matrix of solid tumors and increases the local concentration of cytotoxic payload near the tumor vasculature, enabling the drug to diffuse to the neoplastic mass. Abs of ADCs are occasionally capable of inducing antigen-mediated anticancer activity in addition to the cytotoxicity of the ADC payload [16]. This occurs when the antigen inhibits the downstream signaling of cancer cells when binding with the Ab.

Figure 2.

Mechanistic pathways of antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) internalization and cancer cell killing [2].

Other challenges to targeting tumor antigens with ADCs include high interstitial tumor pressure, physical and kinetic barriers, and a bystander effect associated with the heterogeneous expression of antigen [7]. The bystander effect is a phenomenon of nonspecific systematic toxicity that arises because of the diffusion of the membrane-internalized cytotoxic payload from antigen-positive tumor cells to neighboring antigen-negative healthy cells [17].

Antibody selection

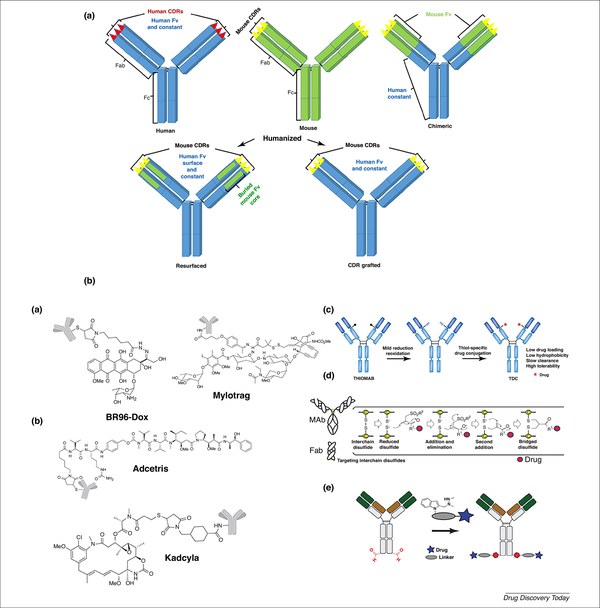

Important properties of Abs in ADCs include their antigen affinity, target specificity, good retention, minimal immunogenicity, low cross-reactivity, and along circulation in plasma. Typically, the binding affinity of the Ab component of ADCs is in the range 0.1–1 nM. Murine Abs were used in first-generation ADCs, which caused severe immunogenicity by producing human antimouse Abs in patients; however, bioengineering research resulted in the discovery of chimerized, humanized, and fully human Abs [6]. Today, most Abs used in humans are either human derived or humanized. Humanized Abs mainly derive from human sources except for the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), which have murine origins. In humanized Abs, mouse CDRs are either grafted or resurfaced to the human Fv surface and constant regions (Figure 3a) [18]. Kadcyla® is an example of a CDR resurfacing humanized ADC. Most Abs in ADCs utilized in clinical trials are human immunoglobulin (Ig)-G isotypes, particularly IgG1. Occasionally, the unmodified Fc regions of Abs bind to Fc-gamma receptors (FcγR) of immune cells, such as macrophages and natural killer cells, and induce Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), resulting in induction of antitumor immune responses [7]. The effects of ADCC and CDC are particularly prominent in human IgG1 isotype mAbs rather than in IgG4, and IgG2 mAbs; for example, trastuzumab, which is the drug in Kadcyla®, was found to initiate ADCC and CDC-associated tumor cell killing.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic representation of fully human (blue), mouse (green), chimeric (fused mouse-originating antigen-binging domain with human constant domain, green-blue) and humanized [fused mouse CDR domain with a human immunoglobulin (Ig)-G backbone] antibody. Fab and Fc are antibody subdomains and Fv is a variable domain. (b) Advances in ADC technologies and representative images of first-generation (i), second-generation (ii) and third-generation (iii) ADCs. Adapted, with permission, from [7] (bi,ii), [76] (biii), [14] (biv) and [66] (bv).

In addition to monospecific Abs, bispecific Abs have been developed to enhance therapeutic functionality. These are used for targeting two antigens of tumor cells and tumor-associated immune cells [19]. In 2014, the FDA approved blinatumomab, a bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [20]. Few reports are available regarding bispecific ADC and most are still in preclinical investigations. One such bispecific ADC is bsHER2xCD63his-ADC, which targets two antigens of cancer cells, HER2 and CD63 (a protein that is responsible for communicating between the cell membrane and intracellular compartments) [20].

Linker selection

The linker has a key role in ADC outcomes because its characteristics substantially impact the therapeutic index, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of the ADC [6,21]. The stable linkers in ADCs can maintain the Ab concentration in the blood circulation and do not release the cytotoxic drug before reaching the target, resulting in minimum off-target effects. However, the linker should be labile enough to rapidly release the cytotoxic drug once the ADC is internalized to the tumor cells [10]. Another critical consideration is how many drug molecules should be loaded onto the Ab: the so-called ‘DAR’. Therefore, optimization of DAR is necessary because attaching too few drug molecules will lead to lower efficacy, whereas attaching too many will alter the pharmacokinetics and further increase instability and toxicity [7]. The FDA has approved ADCs with proven activity that are manufactured by nonspecific conjugation to lysine residues of Abs; however, these generated an undesirable heterogeneous mixture of ADCs, with high DAR values. Therefore, research efforts are directed to the design of homogeneous ADCs with a high number of drug molecules stably linked to the Ab. The aim of most common ADCs is to attain a DAR value close to 4 [10,22].

Cleavable linker

The first type of cleavable linker can be classified into three types: hydrazone, disulfide, and peptide linkers. Each corresponds to a different tumor-specific intracellular condition: low pH sensitive, glutathione sensitive, and protease sensitive, respectively [23]. Acid-sensitive hydrazone linkers, which take advantage of the low pH (4~6) within the endosomes and lysosomes of cancer cells, undergo acid hydrolysis and release the cytotoxic payload [24,25].

Disulfide linkers are more stable in the circulation, and exploit higher concentrations of glutathione within cancer cells. Glutathione concentration is higher in cancer cells, because it is associated with cell survival and tumor growth, and is also elevated during cell stress conditions, such as hypoxia [26–28].

Another form of cleavable linker is a (lysosomal protease-sensitive) peptide, which is more stable than the other forms of cleavable linker discussed above. It also enables improved control of drug release by attaching to the cytotoxic drug with mAbs [29]. Peptide-based linkers are optimized to release their toxic payload upon cleavage by distinct intracellular enzymes (proteases). For example, cathepsin B (a tumor-specific protease) recognizes and cleaves a specific dipeptide bond inside the tumor cells [30,31]. FDA-approved Adcetris® contains a cathepsin B-sensitive dipeptide linkage (valine-citrulline).

Another protease-sensitive linker, β-glucuronide, undergoes degradation and hydrolysis by β-glucuronidase, which is a lysosomal enzyme overexpressed in many cancers and utilized for selective payload release [32]. Burke et al. showed that the PEGylated self-immolative linker, β-glucuronide-conjugated monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), had a DAR value of 8, and enhanced pharmacokinetic stability and potency in xenograft models compared with nonPEGylated linkers [33]. However, more research is required for the clinical improvement of glucuronic acid linker-based ADCs.

Noncleavable linkers

The other class of ADC linker comprises noncleavable thioether or maleimidocaproyl (mc), which both depend on the lysosomal enzymatic degradation of ADC to release the cytotoxic payload after internalizing to cancer cells [34,35]. For example, Kadcyla® was successfully designed to utilize a noncleavable mc-linker that links maytansinoid toxin to the HER2 Ab [36,37]. As a result of the stable linker, Kadcyla® is stable in serum for more than 3 days [38].

The advance design has extended the emergence of innovative linkers for toxic payload conjugation at the linker site instead of the Ab site. For example, SpaceLink Technology, developed by Syntarga, is a highly flexible linker-based ADC [39]. This linker can reversibly attach to the toxic payload and Ab. As a result, this allows the selection and optimization of the payload and linker–payload combination to generate ADCs with maximal therapeutic potency [39]. An excellent example of this promising technology is anti-HER2-duocarmycin conjugates, which exhibit in vivo antitumor efficacy with reduced off-target toxicity [39]. Thus, researchers are currently investigating several other innovative linkers for the safe and efficacious delivery of ADC to treat chronic diseases.

Cytotoxic payloads for ADCs

The effectiveness of ADCs depends on the internalization of the ADC, followed by the release of active cytotoxic molecules inside the cytoplasm of tumor cells. For tumors with insufficient expression of targeting antigens, the potency of the payload should be sufficient to kill the cancer cells, even at low doses [40]. Given that ADCs currently require intravenous administration, it is crucial that the cytotoxic payload exhibits extended stability in the circulation. Apart from these physicochemical features, the chemical structure of cytotoxin should also allow conjugation to the linker while maintaining the internalization property of the Ab and promoting its antitumor effects [41]. The drug payload in the ADC should demonstrate a high potency therapeutic index because it is projected that only approximately 2% of the injected ADC dose will reach the tumor site, resulting in low intracellular drug delivery [2]. A drug that is suitable for use in an ADC should be potent enough to kill aggressively dividing cancer cells but not lethal to healthy cells. In fact, drugs used in clinical trials are limited to six to eight compounds; the majority of these payloads originate from natural product sources, and are categorized as follows [41]: (i) Microtubule inhibitors (DM1, DM4, MMAF, and MMAE); DNA synthesis inhibitors [calicheamicin, doxorubicin, duocarmycin, and pyrrolobenzodiazepines (PBD)]; and (iii) topoisomerase inhibitors [SN-38 (quinoline alkaloids)].

Consequently, an ideal payload for an ADC should have an in vitro subnanomolar IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) value against tumor cell lines and a suitable functional group with adequate solubility in aqueous solutions for chemical conjugation with the Ab and for improving the solubility of the resulting ADC [42,43]. Derivatives of auristatin, maytansinoid, calicheamicin, duocarmycin, PBD, and amanitin are currently being utilized as cytotoxic payloads, and are described below [44].

Auristatin

Auristatin is a dolastatin 10-based auristatin analog [45]. Clinical trials of Dolastatin 10 did not progress because of its nonspecific toxicity. However, its synthetic derivatives MMAE and MMAF are currently used as cytotoxic payloads in ADCs. MMAE and MMAF function as mitotic inhibitors. The first and only FDA-approved auristatin-based ADC is Adcetris®, which is used for lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL) [40]. However, more than ten auristatin-based ADCs are currently in clinical trials [44] (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Clinical trial stage | ADC name | Antibody/Linker | Cytotoxic drugs | Cancer type (s) | Antigen targeted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | ASG-22ME | Hu IgG1/valine-citrulline (V.C) | MMAE | Urothelial and other malignant solid tumors | Nectin-4 |

| SAR566658 | Hz IgG1/DS6 disulfide | Maytansinoid | Malignant neoplasm, triple-negative breast cancer | CA6 | |

| BAY 94–9343 | H IgG1/disulfide, HuIgG1/SPDB | Maytansinoid, (DM4) | Mesothelin-positive solid tumors | Mesothelin | |

| IMGN388 | IgG1/disulfide | Maytansinoid | Solid tumors | Integrin αv | |

| BIIB015 | IgG1/disulfide | Maytansinoid | Anti-Cripto, refractory solid tumors | Cripto-1 | |

| SGN-75 | Anti D70/dipeptide | Auristatin | Renal cell carcinoma | CD70 | |

| AGS-22M6E | Anti-Nectin fully human IgG/dipeptide | Auristatin | Malignant solid tumors | Nectin4 | |

| IMGN529 | K7153A humanized IgG1 thioether | Maytansinoid | B cell malignancies | CD37 | |

| AMG595 | Anti-EGFRvIII fully human IgG1/thioether | Maytansinoid | Glioblastoma | EGFRvIII | |

| RG7593/DCDT2980S | Hz IgG1/valine-citrulline | MMAE | NHL | CD22 | |

| SAR566658 | Hu IgG1/SPDB | Maytansine (DM4) | Solid tumors | CA6 | |

| Labestuzumab-SN-38 | HzIgG1/phenylalanine-lysine | SN38 | Colorectal cancer | CD66e/CEACAM5 | |

| AGS-16C3F | Hu IgG2/maleimidocaproyl | MMAF | Renal cell carcinoma | ENPP3 | |

| SGN-CD33A | Hz | PDB dimer | AML | CD33 | |

| SGN-CD19A | Hz IgG1/maleimidocaproyl | MMAF | B cell lymphoma | CD19 | |

| SGN-LIV1A | Hz IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Metastatic breast cancer | LIV-1 | |

| RG7596 | Hz IgG1/V.C | MMAE | NHL | CD79b | |

| ASG-5ME | Hu IgG2/V.C | MMAE | Pancreatic, gastric, an prostate cancers | SLC44A4 | |

| BAY 79–4620 | Hu IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Advanced solid tumors | CA-IX | |

| AGS-67E | Hu IgG2/V.C | MMAE | Lymphoid malignancies, leukemia | CD37 | |

| AMG-172 | Hu IgG1/MCC | Maytansine (DM1) | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma, renal cell adenocarcinoma and carcinoma | CD27L | |

| AGS15E | Hu IgG2/[cleavable] | MMAE | Metastatic urothelial cancer | SLITRK6 | |

| GSK2857916 | Hz IgG1/maleimidocaproyl | MMAF | Multiple myeloma | BCMA | |

| IMGN289 | SMCC | Maytansine (DM1) | EGFR-positive solid tumors | EGFR | |

| AMG 595 | SMCC | Maytansine DM1 | Advanced malignant glioma, anaplastic astrocytomas, glioblastoma multiforme | EGFRvIII | |

| IMGN242 (huC242-DM4) | Humanized IgG1/huC242 disulfide | Maytansinoid | Solid tumors | CanAg | |

| Phase I/II | Immunomedics (IMMU)-110 (hLL1-DOX) | Milatuzumab hydrazone | Doxorubicin | Multiple myeloma | CD74 |

| Lorvotuzumab mertansine (IMGN901) | Humanized IgG1/huC242 disulfide | Maytansinoid | Multiple myeloma, solid tumors | CD56 | |

| IMMU-132 | Hz IgG1/CL2A | CPT-11 SN38 | Colorectal cancer, gastric adenocarcinoma, esophageal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma | TROP-2 | |

| Milatuzumab doxorubicin | Hz IgG1/hydrazone | Doxorubicin | Multiple myeloma | CD74 | |

| HuMax®-TF | Hu IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Solid tumors | Tissue Factor | |

| Phase II | SAR3419 (huB4-DM4) | huB4/humanized IgG1 disulfide, Hz IgG1/SPDB | DM4 | B cell NHL | CD19 |

| BT062 | ChIgG4/SPDB, anti-CD138 chimeric IgG4 disulfide | DM4 | Multiple myeloma | CD138, Syndecan1 | |

| Glembatumumab vedotin (CDX-011) | Hu IgG2/valine-citrulline, anti-CR011 dipeptide | MMAE | Breast cancer melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma of lung | gpNMB | |

| Anti-PSMA ADC | Hu IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Prostate cancer | PSMA | |

| MLN0264 | Hu IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Gastrointestinal malignancies | Guanylyl cyclase C | |

| Lorvotuzumab mertansine | Hz IgG1/SPP | DM1 | Solid tumors | CD56 | |

| PSMAADC | Anti-PSMA fully human IgG1/dipeptide | Auristatin | Metastatic, hormone-refractory prostate cancer | PSMA | |

| Phase III | Inotuzumab ozogamicin (CMC 544) | Humanized IgG4/G5/44 hydrazone | Calicheamicin | B- cell lymphomas, NHL | CD22 |

| FDA Approved | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (mylotarg®), Now terminated | Hu IgG4/hydrazone | calicheamicin | AML | CD33 |

| Trastuzumab-emtansine (Kadcyla®) | HzIgG1 trastuzumab/thioether | DM1 | Metastatic breast cancer | HER2 | |

| Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) | Ch IgG1/V.C | MMAE | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | CD30 | |

| Terminated | LOP628 | HzIgG1/(noncleavable) | Maytansine | AML/C-Kit-positive solid tumors | cKit |

From clinical trials.gov.

Abbreviations: Ch, chimeric antibody; Hu, fully human; Hz, humanized.

Maytansionids

Maytansinoids (DMs) are thiol derivatives of maytansines and their function is similar to that of Vinca alkaloids. Maytansines bind to the ‘plus’ end of the growing microtubule and block the polymerization of tubulin dimers, thus preventing the formation of mature microtubules [44,46]. However, maytansine derivative (DM1 or DM4)-conjugated ADCs can selectively deliver the payload in cancer cells, thus improving the therapeutic index. Some maytansinoid-based ADCs are currently in clinical trials for solid and hematological cancers [7]. Among these, trastuzumab-DM1 (Kadcyla®), a maytansinoid-linked HER-2-targeting ADC, was approved by the FDA for use against HER-2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Calicheamicin

Calicheamicin, a potent DNA-targeting agent, is used as a toxic payload for ADCs [47]. Calicheamicin recognizes the minor groove of the TCCTAGGA sequence of DNA and inhibits DNA replication [44]. Mylotarg®, a calicheamicin γ1- anti-CD33 conjugate, has an acid-cleavable hydrazone linker. Mylotrag® was withdrawn from market 10 years after its initial approval, because of adverse effects such as premature release of calicheamicin, low conjugation efficiency of drug to Ab, exchange of Fab arm with serum Ab, and unwanted binding of ADC to CD33-positive liver cells [1]. CMC-544, a calicheamicin-linked CD22 (IgG4)-targeting ADC has been pursued in multiple clinical trials for different hematological cancers, such as ALL and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) [48].

Duocarmycin

Duocarmycin, a potent antitumor antibiotic, has an IC50 of 40–100 pM [49]. It targets the minor groove of DNA, where it alkylates adenine bases. Synthetic analogs of duocarmycin, such as CC1065, is are to be a potent payload for ADCs; currently, BMS-936561 (MDX-1203) is in a Phase I clinical trial [50]. CC1065-conjugated ADCs are efficacious against multidrug resistant (MDR) cell lines (DLD-1 and HCT-15) and showed promising in vivo antitumor effect at lower dose [44].

Amatoxin

Amatoxin is a cyclic peptide that binds RNA polymerase II, leading to the inhibition of DNA transcription and ultimately programmed cell death [51]. ChiHEA125-Ama is anti-EpCAM linked to α-amanitin ADC [52].

Other ADC payloads

Some miscellaneous cytotoxic payloads, such as derivatives of PBDs and centanamycin (indole carboxamide), are also considered as potent payloads for ADC development. These molecules bind to double strands of DNA and either alkylate or intercalate the DNA, thereby inhibiting DNA replication. The PBD-containing ADCs (SGN-CD33A and SGN-CD70A) are currently in Phase I clinical trials [44,53] (Table 1). PBDs are naturally produced and intercalate specific regions of DNA within the tumor cell [44]. The blocking of cancer cell division potentially inhibits tumor growth without distorting its DNA helix structure, thereby avoiding emergent drug resistance [54].

Doxorubicin

Doxorubicin binds to DNA by intercalation and inhibits DNA synthesis [55]. For example, milatuzumab-conjugated doxorubicin ADC (IMMU-110) has undergone Phase I/II clinical trials for CD74-positive relapsed multiple myelomas [56].

The primary challenge to developing a new cytotoxic drug is that it should have a high therapeutic index value; therefore, a low dose of drug would be enough to kill the tumor cells, resulting in the reduction of adverse effects.

Advances in ADC technology

Since the breakthrough discovery of the first FDA-approved ADC, Mylotrag®, anticancer therapy research has diversified, resulting in the development of several novel, safer ADCs. Herein, we describe advances in the development of ADCs towards targeted anticancer drug delivery.

First-generation ADCs

The primary focus in the design of first-generation ADCs was faster body clearance to reduce adverse effects. To achieve this, ADCs were made with murine-derived Ab backbones; however, in humans, these generated immunogenic human antimouse Abs, which accelerated the clearance of ADCs by the immune system [44]. The choice of antigen in first-generation ADCs was not specific to tumor cells, resulting in adverse effects. The linkers of ADCs were also not stable enough in the circulation and the toxic payload used was less potent (micromolar IC50 range). For example, BR96-Dox, an anti-Lewis Y-targeting BR96-mAb conjugated with doxorubicin, was terminated in Phase II clinical trials against Lewis Y-expressing epithelial tumors [57]. Similarly, the FDA-approved CD33-targeting Mylotrag® was also withdrawn from market. Both ADCs showed acute adverse effects and morbidity in patients, attributed to acid-labile weak hydrazone linkers and nonspecific antigen expression in healthy cells [58].

Second-generation ADCs

The limitations and failures of first-generation ADCs were eliminated in second-generation ADCs. The premature release of drugs because of the unstable hydrazone linker in Mylotrag® has been avoided in second-generation FDA-approved ADCs, by using different linkers, such as the valine-citrulline (cathepsin cleavable) linker in Adcetris® and a thioester (noncleavable) linker in Kadcyla ®. The cytotoxic payloads used in second-generation ADCs are also more potent than in first-generation ADCs. For example, tubulin-targeting agents, such as MMAE used in Adcetris® is approximately 100–1000-fold stronger than DNA-intercalating doxorubicin of BR96-Dox [59]. The IC50 of MMAE is approximately 1 nM in different human cancer cell lines, whereas doxorubicin IC50 is in the 1–6 μM range [60]. Despite the improvement in cytotoxic payloads and the introduction of stable linkers, second-generation ADCs have significant limitations in terms of their heterogeneous DAR, resulting from stochastic coupling strategies between the Ab and drug [61]. Typically, chemical conjugation between the drug and Ab occurs via the lysine or cysteine residue of the mAb, which generates DAR (range 0–8) with an average value of 3–4. Therefore, heterogeneous ADCs can contain a mixture of unconjugated, partially conjugated, and overconjugated Abs and, therefore, there will be competition between unconjugated Abs and drug-conjugated species for antigen binding that can diminish the activity of the ADC. By contrast, overconjugation of the drug to the Ab can result in Ab aggregation, a decrease in stability, incremental increases in nonspecific toxicity, and a reduction in the half-life of ADCs in the circulation [22]. Overall, heterogeneous ADCs have a limited therapeutic index and tumor penetration abilities, which are associated with the induction of drug resistant in the tumor microenvironment.

Third-generation ADCs

The aforementioned concerns regarding the heterogeneous DARs of second-generation ADCs have been addressed in third-generation ADCs. Site-specific conjugation has been introduced to produce homogenous ADCs with well-characterized DARs and desired cytotoxicities [62]. The site-specific conjugation of the drug to Ab provides a single-isomer ADC with a uniform DAR value. Such ADCs can be made using bioengineered Abs containing site-specific amino acids, such as cysteine, glycan, or peptide tags [63]. For example, precise site-specific conjugation of MMAE to human IgG was developed by replacing the Ala114 amino acid of the CH1 domain of the IgG Ab with cysteine to create a selectively engineered Ab, called THIOMAB [64]. The site-specific coupling of drug with THIOMAB creates THIOMAB drug conjugates (TDCs) that have homogeneous DARs, low hydrophobicity, and better safety profile for patients [62]. Alternative approaches to site-specific drug conjugation include: (i) a thio-bridge approach that links drugs to the interchain disulfide bond of Abs (four per mAb) [14]; (ii) introduction of unnatural amino acids, such as p-acetylphenylalanine, or noncanonical amino acids, such as phenylselenocysteine, using a encoded gene of the amber stop codon (TAG), along with corresponding orthogonal tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase [65]. Recently, a novel chemoenzymatic approach, SMARTag™, was used for the site-selective modification of Abs that generated uniform DAR in ADCs. In this method, the formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE) recognition sequence was inserted at a specific location in the Ab backbone using molecular biology techniques. In eukaryotic cell FGE, an endogenous enzyme of eukaryotic cells catalyzes the conversion of the cystine to a formylglycine residue (fGly) [66]. The aldehyde group of fGly is involved in the site-specific reaction of drugs, such as PBDs, auristatin, and duocarmycin. SMARTag™-based ADCs, such as CD22–4AP, are a proprietary technology of Catalent’s pharma solution and preclinical studies of CD22–4AP showed it to have a promising therapeutic index with minimum adverse effects and to avoid the development of drug resistance. Similarly, other enzymatic strategies, such as SMAC-TAG™ and TG-ADC™, have been developed for site-specific ADC preparation [67] (Figure 3b). Efforts are continuing to develop more efficient cytotoxic payloads in third-generation ADCs so that a smaller amount of drug is needed to achieve the desired therapeutic effect and to eliminate drug-resistant tumor cells. The development of PBDs, derivatives of tricyclic antibiotics, has attracted interest over other DNA-alkylating agents. PBDs are potent compounds, some of which have subpicomolar IC50 and do not show cross-resistance with other chemotherapeutics, such as cisplatin [68]. Four PBD-containing ADCs are currently in clinical trials: SC16LD6.5 is in Phase II trials for small cell lung carcinoma; SGN-CD33A is in Phase II trials for AML; SGN-CD70A is used to treat patients with CD70-positive cancer, and ADCT-301 is in Phase I trials for CD25 lymphoma [69].

Clinical trials of ADCs

The FDA withdrawal of mylotarg® (10 years after its initial approval) was a lesson learned for redesigning ADC components. Researchers have made significant progress in improving conjugation technology, Ab bioengineering, linker chemistry, and the identification of potent drugs has resulted in more successful clinical outcomes for ADCs (Table 1). This led to the FDA approval of Adcetris® and Kadcyla®, and additional clinical trials, such as 50 active trials for solid tumors and 20 active clinical trials for hematological cancers [44,70]. Pharma Source’s trend reports (www.pharmsource.com/trend/adc-market-opportunity-for-cmos) on ADCs reported that more than 15 clinical trials were pursued in 2015, six to eight trials were completed in 2016, and that this trend will continue in 2017. The promising ADC, inotuzumab ozogamicin (CMC 544), was recently withdrawn for the treatment of relapsed NHL. However, CMC-544 is in active Phase III trials for ALL, and was recognized as an orphan drug by the FDA. Some Phase I trials show some success in the use of drugs from the maytansinoid or auristatin classes of molecules for various cancers. Furthermore, the most commonly used Ab is IgG1, although there are trials on going with IgG2 and IgG4. Despite the strong clinical outcome, the cost of ADC development remains a major limitation. For example, the cost of treatment with the mAb trastuzumab is approximately US$50 000 per year, and the price almost doubles for the trastuzumab-DM1 conjugate Kadcyla®. The development of ADCs is currently directed at decreasing the costs of production by using cheaper nonanimal recombinant mAb technologies and repurposing existing drugs [71]. Therefore, based on the success rate of these clinical trials, it is evident that there is much scope for the further study of ADCs.

Concluding remarks: challenges and hope for ADCs

Extensive research is on going to improve all the components of ADCs that can enhance their targetability and therapeutic efficacy against tumors. A better understanding of ADC-targeting strategies can speed up the FDA approval rate of ADCs and drastically increase the number of clinical trials, especially in solid tumors. However, the failure of some ADCs, such as Mylotrag®, IMGN242-for gastric cancer in Phase II trials, and SGN15-for ovarian cancer in Phase II trials, is mostly attributed to payload-related toxicity and low therapeutic index [44]. These limitations are being addressed in various ways, such as the development of homogenous ADCs with narrowed DARs, using bispecific Ab with enzyme-activated linkers, and high potent payloads [20,69]. Another challenge to the clinical success of ADCs is the evaluation of viable biomarkers, which will ensure the effectiveness of ADCs for selective cancer targeting. Immunohistology (IHC) is a widely used method of determining antigen expression and requires tissue biopsies, which sometimes limits its use. Recently, other efforts, such as the use of circulating tumor cells and imaging techniques, avoid the limitations of IHC-based methods and are being used to determine the patient population likely to respond to ADC therapy [72]. Another approach to increasing the binding affinity of ADCs is to use protein scaffolds, which have well-defined 3D polypeptide frameworks and their binding affinity to antigens is in the nM to pM range. Clinically utilized protein scaffolds are categorized into two classes: non-Ig scaffolds, such as the Kunitz domain scaffold-based DX88 and affibody scaffold-based ABY-220; and Ab-derived scaffolds, such as the BiTE scaffold-based blinatumomab and nanobody scaffold-based Alx-0141 [73]. These scaffolds appear promising in the development of higher-affinity ADCs. A major hurdle to ADCs targeting solid tumors is the tumor stroma, which is a thick, connective, functionally supportive framework layer comprising tumor and nontumor cells. This tumor stroma has been identified as crucial factor in promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune suppression. Recently, emphasis has shifted to inhibiting fibroblast activation protein (FAP)-expressing tumor stromal cells [74]. FAP-targeting mAbs are still in development and only a few have been utilized in clinical trials. Therefore, it is hoped that, in the near future, tumor stroma-targeting ADC could open a new therapeutic window for the treatment of solid tumors.

highlights.

ADC represents a new class of targeted anticancer therapeutics

Elucidates selection criteria for tumor specific antigen and ADC development

Smart linkers and fixed DAR value for reducing side effects of ADCs are covered

Current clinical trial trends and market prediction of ADCs are summarized

Acknowledgments

K.T. would like to acknowledge an AGRADE scholarship from the Wayne State University Graduate School to pursue MSc studies in the Iyer Lab, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Wayne State University. A.K.I. acknowledges US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) grant R21CA179652 and Wayne State University start-up funding for research support.

Footnotes

Teaser: Discovery of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) bridged together by smart linkers created a powerful entity that can deliver highly efficacious anticancer agents targeted to tumor cells and tissues with an improved therapeutic window. Advancement of protein engineering, linker chemistry, and new cytotoxic payloads herald ADCs as safe and effective anticancer therapeutics for personalized medicine.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Diamantis N and Banerji U (2016) Antibody-drug conjugates: an emerging class of cancer treatment. Br. J. Cancer 114, 362–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters C and Brown S (2015) Antibody-drug conjugates as novel anti-cancer chemotherapeutics. Biosci. Rep 35, e00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott AM et al. (2012) Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 278–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chabner B and Roberts TG (2005) Timeline: chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szakacs G et al. (2006) Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 5, 219–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes B (2010) Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer: poised to deliver? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 9, 665–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez HL et a(2014) l. Antibody-drug conjugates: current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today 19, 869–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jilani I et al. (2002) Differences in CD33 intensity between various myeloid neoplasms. Am. J. Clin. Pathol 118, 560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaghy H (2016) Effects of antibody, drug and linker on the preclinical and clinical toxicities of antibody-drug conjugates. MAbs 8, 659–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teicher BA and Chari RVJ (2011) Antibody conjugate therapeutics: challenges and potential. Clin. Cancer Res 17, 6389–6397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kononen J et al. (1998) Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat. Med 4, 844–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taneja SS (2004) ProstaScint® Scan: contemporary use in clinical practice. Rev. Urol 6, 19–28 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad AM (2007) Recent advances in pharmacokinetic modeling. Biopharm. Drug Dispos 28, 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badescu G et al. (2014) Bridging disulfides for stable and defined antibody drug conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem 25, 1124–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perrino E et al. (2014) Curative properties of noninternalizing antibody-drug conjugates based on maytansinoids. Cancer Res. 74, 2569–2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubská L et al. (2005) HER2 signaling downregulation by trastuzumab and suppression of the PI3K/Akt pathway: an unexpected effect on TRAIL-induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 579, 4149–4145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh AP et al. (2016) Quantitative characterization of in vitro bystander effect of antibody-drug conjugates. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 43, 567–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imai. K and Takaoka A (2006) Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 714–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter PJ. and Senter PD. (2008) Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Cancer J. 14, 154–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Goeij BE. et al. (2016) Efficient payload delivery by a bispecific antibody-drug conjugate targeting HER2 and CD63. Mol. Cancer Ther 15, 2688–2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nolting B (2013) Linker technologies for antibody--drug conjugates. Antibody-Drug Conjug. 2013, 71–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamblett KJ et al. (2004) Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res 10, 7063–7070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mo R and Gu Z (2016) Tumor microenvironment and intracellular signal-activated nanomaterials for anticancer drug delivery. Mater. Today 19, 274–283 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil R et al. (2012) Cellular delivery of doxorubicin via pH-controlled hydrazone linkage using multifunctional nano vehicle based on poly(β-l-malic acid). Int. J. Mol. Sci 13, 11681–11693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fishkin N et al. (2010) Maytansinoid release from thioether linked antibody maytansine conjugates (AMCs) under oxidative conditions: Implication for formulation and for ex vivo sample analysis in pharmacokinetic studies. Cancer Res. 70, 4398 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balendiran GK et al. (2004) The role of glutathione in cancer. Cell. Biochem. Funct 22, 343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kigawa J et al. (1998) Glutathione concentration may be a useful predictor of response to second-line chemotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer 82, 697–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shefet-Carasso L and Benhar I (2015) Antibody-targeted drugs and drug resistance—challenges and solutions. Drug Resist. Updat 18, 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanderson RJ et al. (2005) In vivo drug-linker stability of an anti-CD30 dipeptide-linked auristatin immunoconjugate. Clin. Cancer Res 11, 843–852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason SD and Joyce JA (2011) Proteolytic networks in cancer. Trends Cell Biol 21, 228–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koblinski JE et al. (2000) Unraveling the role of proteases in cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 291, 113–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaracz S et al. (2005) Recent advances in tumor-targeting anticancer drug conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem 13, 5043–5054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burke PJ et al. (2009) Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of antibody-drug conjugates comprised of potent camptothecin analogues. Bioconjug. Chem 20, 1242–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doronina SO et al. (2006) Enhanced activity of monomethylauristatin F through monoclonal antibody delivery: effects of linker technology on efficacy and toxicity. Bioconjug. Chem 17, 114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson HK et al. (2006) Antibody-maytansinoid conjugates are activated in targeted cancer cells by lysosomal degradation and linkerdependent intracellular processing. Cancer Res. 66, 4426–4433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LoRusso PM et al. (2011) Trastuzumab emtansine: a unique antibody-drug conjugate in development for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2--positive cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 17, 6437–6447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dosio F et al. (2011) Immunotoxins and anticancer drug conjugate assemblies: the role of the linkage between components. Toxins (Basel) 3, 848–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girish S et al. (2012) Clinical pharmacology of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1): an antibody--drug conjugate in development for the treatment of HER2-positive cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 69, 1229–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Groot FMH et al. (2007) Elongated and multiple spacers in activatible prodrugs. Application number: US 10/472,921. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shefet-Carasso L and Benhar I (2015) Antibody-targeted drugs and drug resistance: challenges and solutions. Drug Resist. Updat 18, 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouchard H et al. (2014) Antibody-drug conjugates—a new wave of cancer drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 24, 5357–5363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akkapeddi P et al. (2016) Construction of homogeneous antibody–drug conjugates using site-selective protein chemistry. Chem. Sci 7, 2954–2963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hallen HE et al. (2007) Gene family encoding the major toxins of lethal Amanita mushrooms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 19097–19101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim EG and Kim KM (2015) Strategies and advancement in antibody-drug conjugate optimization for targeted cancer therapeutics. Biomol. Ther 23, 493–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettitj R (1990) Binding of dolastatin 10 to tubulin at a distinct site for peptide antimitotic agents near the exchangeable nucleotide and vinca alkaloid sites. Journal title 265, 17141–17149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan MA and Wilson L (2004) Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noguez C and Hidalgo F (2014) Ab initio electronic circular dichroism of fullerenes, single-walled carbon nanotubes, and ligand-protected metal nanoparticles. Chirality 26, 553–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeshita A et al. (2009) CMC-544 (inotuzumab ozogamicin) shows less effect on multidrug resistant cells: Analyses in cell lines and cells from patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol 146, 34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ichimura M et al. (1991) Duocarmycins, new antitumor antibiotics produced by Streptomyces; producing organisms and improved production. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 44, 1045–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owonikoko TK et al. (2016) First-in-human multicenter phase i study of BMS-936561 (MDX-1203), an antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD70. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 77, 155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott AM et al. (2007) A phase I clinical trial with monoclonal antibody ch806 targeting transitional state and mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 4071–4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moldenhauer G et al. (2012) Therapeutic potential of amanitin-conjugated anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule monoclonal antibody against pancreatic carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 104, 622–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kung Sutherland MS et al. (2013) SGN-CD33A: a novel CD33-targeting antibody-drug conjugate using a pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer is active in models of drug-resistant AML. Blood 122, 1455–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartley JA (2011) The development of pyrrolobenzodiazepines as antitumour agents. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 20, 733–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacar O et al. (2013) Doxorubicin: an update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Pharmacol 65, 157–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Govindan SV et al. (2013) Milatuzumab-SN-38 conjugates for the treatment of CD74+ cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther 12, 968–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saleh BMN et al. (2000) Phase I trial of the anti-Lewis Y drug immunoconjugate BR96-doxorubicin in patients with Lewis Y-expressing epithelial tumors. J. Clin. Oncol 18, 2282–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ten Cate B et al. (2009) A novel AML-selective TRAIL fusion protein that is superior to Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in terms of in vitro selectivity, activity and stability. Leukemia 23, 1389–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vankemmelbeke M and Durrant L (2015) Third-generation antibody drug conjugates for cancer therapy--a balancing act. Ther. Deliv 6, 1239–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koga Y et al. (2015) Antitumor effect of antitissue factor antibody-MMAE conjugate in human pancreatic tumor xenografts. Int. J. Cancer 137, 1457–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sochaj AM et al. (2015) Current methods for the synthesis of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates. Biotechnol. Adv 33, 775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Junutula JR et al. (2008) Site-specific conjugation of a cytotoxic drug to an antibody improves the therapeutic index. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 925–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agarwal P and Bertozzi CR (2015) Site-specific antibody-drug conjugates: the nexus of bioorthogonal chemistry, protein engineering, and drug development. Bioconjug. Chem 26, 176–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhakta S et al. (2013) Engineering THIOMABs for site-specific conjugation of thiol-reactive linkers. Antibody-Drug Conjug. 2013, 189–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu CC and Schultz PG (2010) Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Annu, Rev, Biochem 79, 413–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drake PM et al. (2014) Aldehyde tag coupled with HIPS chemistry enables the production of ADCs conjugated site-specifically to different antibody regions with distinct in vivo efficacy and PK outcomes. Bioconjug. Chem 25, 1331–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beerli RR et al. (2015) Sortase enzyme-mediated generation of site-specifically conjugated antibody drug conjugates with high In vitro and In vivo potency. PLoS ONE 10, 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman KM et al. (2013) GC-targeted C8-linked pyrrolobenzodiazepine--biaryl conjugates with femtomolar in vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo antitumor activity in mouse models. J. Med. Chem 56, 2911–2935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flynn MJ et al. (2016) ADCT-301, a pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer-containing antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) targeting CD25expressing hematological malignancies. Mol. Cancer Ther 15, 2709–2721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Goeij BECG and Lambert JM (2016) New developments for antibody-drug conjugate-based therapeutic approaches. Curr. Opin. Immunol 40, 14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brian K (2009) Industrialization of MAb production technology. MAbs 2009, 443–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krebs MG et al. (2010) Circulating tumour cells: their utility in cancer management and predicting outcomes. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol 2, 351–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weidle H et al. (2013) The emerging role of new protein scaffold-based agents for treatment of cancer. Cancergenomics Proteomics 10, 155–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.López-Juárez¥ A et al. (2012) NIH Public Access. Journal title 100, 130–134 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas A et al. (2016) Antibody???drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 17, e254–e262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Damle NK (2008) Antibody-drug conjugates ace the tolerability test. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 884–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]