Abstract

Wolbachia is an endosymbiotic Alphaproteobacteria that can suppress insect-borne diseases through decreasing host virus transmission (population replacement) or through decreasing host population density (population suppression). We contrast natural Wolbachia infections in insect populations with Wolbachia transinfections in mosquitoes to gain insights into factors potentially affecting the long-term success of Wolbachia releases. Natural Wolbachia infections can spread rapidly, whereas the slow spread of transinfections is governed by deleterious effects on host fitness and demographic factors. Cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) generated by Wolbachia is central to both population replacement and suppression programs, but CI in nature can be variable and evolve, as can Wolbachia fitness effects and virus blocking. Wolbachia spread is also influenced by environmental factors that decrease Wolbachia titer and reduce maternal Wolbachia transmission frequency. More information is needed on the interactions between Wolbachia and host nuclear/mitochondrial genomes, the interaction between invasion success and local ecological factors, and the long-term stability of Wolbachia-mediated virus blocking.

Keywords: transinfections, fitness costs, dengue, biocontrol, vector suppression, vector replacement

1. INTRODUCTION

Wolbachia is a genus of common intracellular bacterial endosymbionts, prevalent in insects and other arthropods. Recent estimates suggest that approximately one-half of insect species are infected (148), with infection incidence perhaps lower for aquatic insects (120). Infection frequencies in natural populations are variable, ranging from near 100% to very rare, both within and among species (121). Wolbachia is particularly common in some insect orders, such as Diptera and Hemiptera, but lower in others, such as Ephemeroptera (mayflies) (120). Most Wolbachia infections have been detected with molecular probes, and few have been characterized for any phenotypic effects, including cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI)—increased embryo mortality when Wolbachia-infected males mate with uninfected females or with females carrying an incompatible Wolbachia infection (74). Disease applications depend on Wolbachia’s abilities to induce CI and suppress the growth of disease-causing microbes within its hosts.

1.1. Wolbachia

Like mitochondria, Wolbachia is normally maternally inherited—but Wolbachia transmission is often imperfect. Some Wolbachia infections show near-perfect maternal transmission (79), but others show transmission rates as low as 80% (96). High rates of maternal transmission likely reflect tissue tropism, particularly strong associations with ovary tissues (135). Discordance between the phylogenies of Wolbachia and its hosts or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes, which occurs across insect orders and within species, demonstrates horizontal transmission (100). Intraspecific examples include herbivory-based transmission in whiteflies (76) and horizontal transmission in Trichogramma (63). However, the most extensively sampled species, especially of Drosophila and Culex, reveal near-complete concordance of intraspecific mitochondrial and Wolbachia phylogenies, suggesting that horizontal transmission is generally rare, at least in these taxa (9, 140).

Wolbachia is known for reproductive manipulations (101), especially CI (58). CI produces a frequency-dependent fitness advantage for Wolbachia-infected females that can drive the spread of Wolbachia within and among populations. When Wolbachia produces deleterious fitness effects, CI can drive spatial spread only once the local Wolbachia frequency exceeds a threshold value over a sufficiently large area (15, 122, 139). Despite the importance of CI in driving frequency increases, once Wolbachia has established in a host species, selection on Wolbachia variants within that host species focuses on enhancing host fitness and ensuring reliable maternal transmission (137), with essentially no selection to intensify or maintain CI, even with population subdivision and local density effects (51). These patterns of selection promote the evolution of mutualistic phenotypes. One such mutualistic effect, critical for many applications, is the suppression of viruses and other microbes within infected host individuals, first demonstrated in laboratory settings (91, 131).

Studies of Wolbachia transinfections are being explored through microinjection into new hosts to inhibit the spread of vector-borne diseases in two ways: as agents of population suppression (analogous to sterile-male release) and as agents of population replacement (Table 1). Both rely on CI, and they are not mutually exclusive, given that suppression can facilitate replacement (59) and replacement can reduce or even crash populations owing to deleterious Wolbachia effects (113). The suppression approach was first applied on a field population in 1967 (Table 1). Male-only releases are used to effectively sterilize resident females; analogous sterile-male releases have controlled many agricultural invertebrate pests, such as true fruit flies (34). Males were traditionally sterilized by radiation; now some releases use Wolbachia-infected males subjected to low-dose radiation, which leaves males fertile but sterilizes females that might be accidentally released (155).

Table 1.

Field releases of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes for population replacement and suppression interventions around the world

| Mosquito species | Wolbachia variant | Objective | Location | First release | Outcome | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culex pipiens fatigans | wPip (Paris variant) | Suppression | Okpo (Burma) | February 1967 | Eradication of mosquitoes in a small trial area | 75 |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | wPip (Paris variant) | Suppression | Delhi (India) | August 1973 | Reduction in population size and female fertility in release areas | 33 |

| Aedes polynesiensis | wRiv | Suppression | French Polynesia | December 2009 | Reduction in population size and female fertility in release areas; releases are ongoing | 99, 128 |

| Aedes aegypti | wMel | Replacement | Cairns and Townsville (Australia), Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Yogyakarta (Indonesia), Tri Nguyen Island (Vietnam), and others | January 2011 | Establishment of wMel in release areas where it remains at a high frequency in most locations; releases are under way in several countries | 42, 54, 55, 102, 122; https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/ |

| Aedes aegypti | wMelPop | Replacement | Cairns (Australia) and Tri Nguyen Island (Vietnam) | January 2012 | wMelPop reached high frequencies during active releases and then declined rapidly after releases stopped | 98 |

| Aedes albopictus | wPip | Suppression | Kentucky, California, and New York (United States) | June 2014 | Reduction in population size and female fertility in release areas | 82; https://mosquitomate.com/?v=3.0 |

| Aedes albopictus | wPip/wAlbA/wAlbB | Suppression | Guangzhou (China) | April 2015 | Population suppression of >95% in release areas | 157 |

| Aedes aegypti | wAlbB | Suppression | Singapore, Clovis and Fresno (California), South Miami and Stock Island (Florida), Innisfail (Australia) | August 2016 | Variable population suppression achieved but averaged 95% in one area (Fresno) | 83, 97; https://debug.com/ |

| Aedes aegypti | wAlbB | Replacement | Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia) | February 2017 | Establishment of wAlbB in three populations in which it remains at a high frequency after releases stopped | W.A. Nazni, unpublished data |

Releases are listed chronologically.

Replacement in a natural population was first successfully implemented in 2011 near Cairns, Australia (55) (Table 1), and preliminary data suggest that this intervention has significantly reduced dengue transmission (111). This approach uses CI to drive Wolbachia variants that inhibit disease transmission, even when they might reduce host fitness, into a vector population. Other Wolbachia-based strategies, such as suppressing populations using Wolbachia with environment-dependent deleterious effects, have been proposed (81, 107). Replacement is undertaken under permissive conditions, in which the transinfection is relatively benign but the population would crash when the Wolbachia becomes severely deleterious. Because of their pervasiveness in nature and lack of genetic modification, Wolbachia variants are regarded as biocontrol agents. This contributes to greater public acceptance of Wolbachia-based strategies than of genetically modified organisms (89), with fewer risks identified (95).

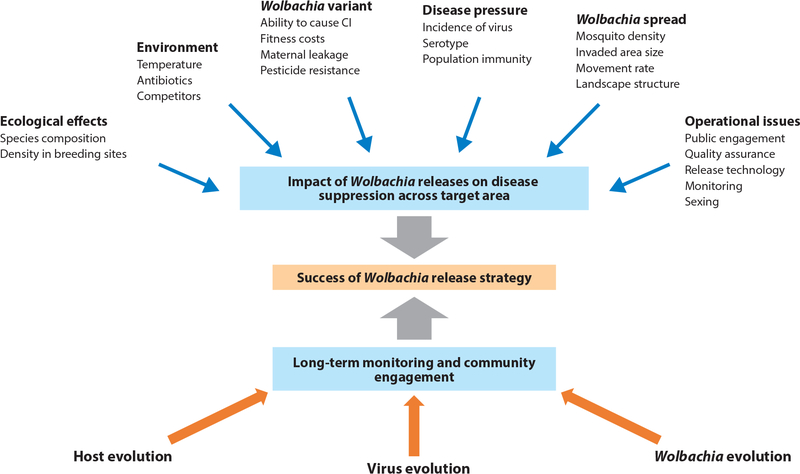

Although releases of multiple Wolbachia variants, involving both suppression and replacement, are now being undertaken around the world, there are challenges in their application (Figure 1). Some revolve around the long-term stability of Wolbachia effects, which depends on a tripartite system of host, Wolbachia, and other microbes, including those that cause disease, interacting within a domestic landscape. Other issues involve the feasibility of widespread releases, especially of those undertaken by public health authorities with less quality control than scientific trials.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing the success of Wolbachia releases during and after the releases. Wolbachia population replacement and suppression are influenced by features of the Wolbachia variant, mosquito host factors, production issues, and environmental factors. Long-term disease suppression may be affected by evolutionary changes in the mosquito host, virus, or Wolbachia and by a public commitment to maintain surveillance and perform additional releases as required. Abbreviation: CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility.

Our aim is to explore these challenges within an evolutionary and ecological genetic context. How do we identify useful Wolbachia variants, likely to have desirable phenotypic effects for alternative strategies, and maintain stability in the longer term? Which ecological and evolutionary issues need to be considered to ensure effective release programs, minimizing the number of releases required and maximizing spread? Is there evidence for interactions between Wolbachia and host genomes that might threaten a Wolbachia strategy or enhance its effectiveness? What environmental effects need to be considered in a successful Wolbachia strategy, and do these effects place limits on suitable variants for different contexts? We link findings from natural Wolbachia infections to applications in disease vector organisms. This requires understanding the similarities and differences between natural infections and human-introduced transinfections.

1.2. Dynamics of Transinfections Versus Natural Wolbachia Infections

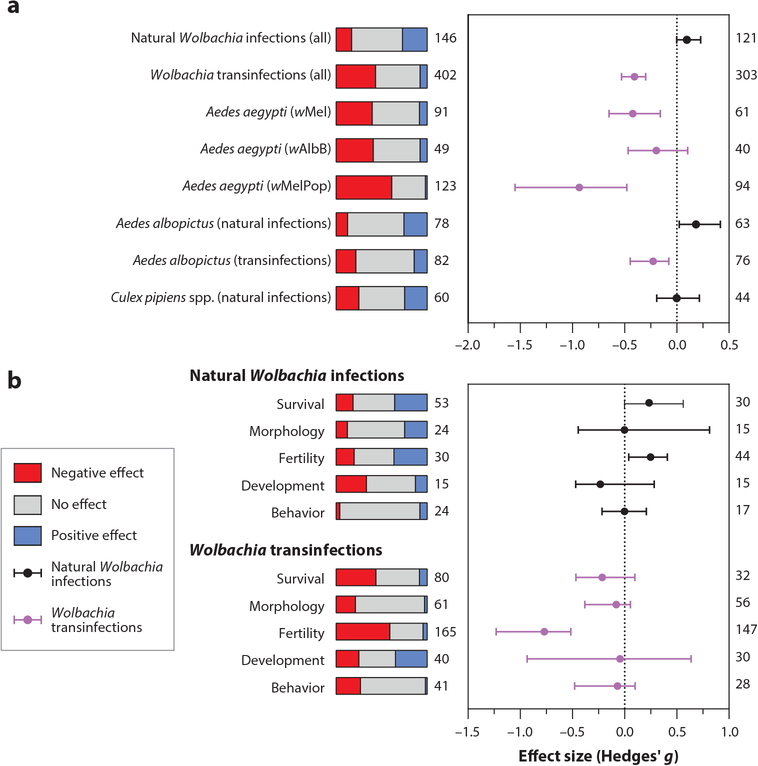

Initial Wolbachia transinfections involved moving strains between Drosophila species (57, 62). However, over 20 Wolbachia variants have now been introduced into disease vector mosquitoes, in which they exhibit heterogeneous effects on fitness, reproduction, and virus interference (Supplemental Table 1). Wolbachia effects can change dramatically from native to novel hosts (145). In general, however, Wolbachia transinfections generated to date decrease host fecundity and viability (Figure 2) while causing CI and perhaps suppressing disease-causing microbes. The combination of CI, which provides a positive frequency-dependent fitness advantage to the Wolbachia, and deleterious effects on host fitness produces bistable frequency dynamics under which the Wolbachia infection frequency must exceed a threshold, the unstable equilibrium, denoted , for the infection frequency to tend to rise (26, 60, 138). Below , deleterious effects dominate and infection frequencies tend to decline. Occasionally, stochastic sampling effects, analogous to genetic drift, can move frequencies of fitness-decreasing Wolbachia infections above the unstable equilibrium, leading to local establishment (65) and possibly spatial spread (15). Fitness variation will also arise among individuals owing to demographic effects (49).

Figure 2.

Effects of Wolbachia infections on mosquito fitness traits. Data were extracted from 75 studies that compared the fitness of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes with that of uninfected mosquitoes. Shaded bars represent the proportion of traits on which Wolbachia infections had a negative (red), positive (blue), or no statistically significant (P > 0.05) effect (gray) on fitness according to statistical tests by the authors. Magnitudes of fitness effects are expressed in terms of effect sizes (Hedges’ g), where dots and error bars represent medians and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. Numbers to the right of the colored bars indicate the number of fitness estimates reported by the authors in each category. Numbers to the right of the effect-size chart are the number of estimated effects, often smaller than the number of fitness estimates because data needed to estimate effect sizes were not provided with all fitness estimates (an exception is fecundity for natural Wolbachia infections, where we were able to calculate some effect sizes, even when authors did not report statistical analyses of effects). Supplemental Data Set 1 provides the data and describes how they were compiled. Effects are shown separately for natural Wolbachia infections (black error bars) and Wolbachia transinfections (purple error bars). (a) Effects are separated by mosquito species and Wolbachia infection type (natural or transinfection). For Aedes aegypti, for which more data were available, effects are shown separately for three of the most-studied Wolbachia variants. (b) Fitness effects are separated into different trait types for natural Wolbachia infections and transinfections.

Cumulative data point to a qualitative distinction between natural Wolbachia infections and human-mediated transinfections. The first example of Wolbachia spatial spread involved variant wRi spreading northward through California Drosophila simulans at roughly 100 km/year (141, 142). When Wolbachia infection frequencies are low, CI has a negligible effect on frequency dynamics, which is dominated by the relative fitness of infected females, denoted F, and maternal transmission frequency, 1 − μ, where μ denotes the fraction of uninfected ova produced by in fected females. When F(1 − μ) < 1, rare infections tend to be eliminated; but a sufficient level of CI can produce bistable dynamics. Prior to work by Weeks et al. (147), several studies demonstrated that wRi-infected D. simulans produced fewer eggs than uninfected females in the laboratory, with typical estimates of relative fecundity near 0.9–0.95. Moreover, wild-caught wRi-infected D. simulans typically produce 4–5% uninfected ova (24). These data indicated F(1 − μ) < 1, so Turelli & Hoffmann (141, 142) conjectured that wRi spread despite bistable dynamics. The hypothesis that fitness-decreasing Wolbachia might spread rapidly in nature motivated proposals for disease control via Wolbachia-based population replacement strategies (101). However, rapid spatial spread of wRi and other natural Wolbachia infections (e.g., 12) is difficult to reconcile with the mathematical theory for bistable waves (discussed in Section 6.2.2), which anticipates the slow spatial spread, on the order of 100–200 m/year, observed for Wolbachia transinfections in Australian Aedes aegypti (122).

A more plausible view is that natural Wolbachia infections, unlike transinfections, often confer net fitness advantages, producing F(1 − μ) > 1, and hence tend to increase when rare. This must be true for natural infections, such as wAu in D. simulans, that produce no detectable reproductive effects (or minimal effects) and are imperfectly maternally transmitted, yet spread in nature (58). These infections may represent an evolutionary progression from strong to weaker CI (90, 137); CI is not favored by selection on Wolbachia within host lineages, so it can be reduced as Wolbachia evolves to reduce costs to female hosts or increase maternal transmission (136), and it can be suppressed by host evolution. However, this progression may be a slow process, since at least for the wRi infection there has been no change in CI under field or laboratory conditions across several decades (24) despite theoretical expectations.

2. WOLBACHIA AND VIRUS BLOCKING

Wolbachia-mediated protection in arbovirus vectors is an area of increasing interest, with over 50 studies of Ae. aegypti alone. Most studies demonstrate that Wolbachia reduces infection or transmission of pathogens but there are exceptions (e.g., 35, 45). The extent of virus blocking provided by transinfected Wolbachia depends on the Wolbachia variant and host species as well as on the nature of the virus (4, 39, 150). For the wMel infection, which is the best studied and is now being released into the field, the extent of virus blocking is variable (25) and can differ between studies. Virus blocking depends on virus serotype, titer, mosquito genetic background, rearing conditions, and the method of infection; thus, methodological differences between studies may produce different outcomes (149).

Virus blocking has been linked to Wolbachia density (84), although some high-density variants do not seem to block, such as wAlbA when transferred to Ae. aegypti (4). Virus blocking may also depend on tissue distribution and effects on lipid pools needed for viral replication. In Drosophila, virus protection correlates with higher Wolbachia density in the head, gut, and Malpighian tubules (103), while in mosquitoes high densities in the midgut and salivary glands are thought to be important for dengue inhibition. Some variation in blocking levels may be related to viral dose. Recent data on wMel (68) suggest low protection or even increased transmission when dengue dose is low, whereas protection appears stronger at high doses. This variability may still allow population-level reduction of viral transmission by Wolbachia, but variability must be considered when assessing overall effects and evolutionary dynamics (68).

Virus blocking may depend on the novelty of Wolbachia–host association. Multiple mechanisms are involved in blocking but novelty may be important for immune upregulation (78, 132). This is evident from the blocking caused by Wolbachia newly transferred to hosts, typified by Ae. aegypti, in which several Wolbachia variants block dengue virus (4, 91, 146). Conversely, blocking associated with native Wolbachia variants in Aedes species such as Ae. albopictus and Ae. polynesiensis appears weak or variable (16, 93), whereas novel Wolbachia transinfections in these species significantly block dengue and Zika viruses (16, 92). Virus blocking may relate to certain types of reproductive manipulations, but this needs further study particularly given that male-killing Wolbachia can also inhibit viruses, as demonstrated for Drosophila pandora (8).

Currently, there is little evidence that Wolbachia-based interventions will lead to increased disease virulence or will be rapidly circumvented by viruses (18), but this area requires more research. Across evolutionary time, virus blocking may evolve through changes in host genes, Wolbachia genes, or both. There may be a downregulation of virus blocking due to costs associated with mounting an immune response, which is countered by any ongoing selection for virus blocking in natural populations.

Virus blocking is not critical to Wolbachia; some natural variants that do not block viral transmission persist in host populations (86, 104). Wolbachia from natural populations is expected to block more effectively when arboviruses are detrimental—a condition met in assays of virus blocking in Drosophila where viruses often reduce longevity (52, 131). Apart from selection mediated through host fitness, virus blocking by Wolbachia should be favored if it increases Wolbachia transmission to offspring.

There is currently little information on whether natural Wolbachia infections effectively block viruses in the field, or on any interactions between blocking and host fitness or maternal transmission. For wMel in Drosophila, the evidence for such blocking looks weak so far; in flies isolated from the same field population in which the Wolbachia infection was either present or absent, there was no association between Wolbachia and either viral load overall or the presence/absence of specific viruses (126). This is an area where additional data, particularly for disease vectors, are needed.

3. FITNESS EFFECTS OF WOLBACHIA

Fitness is an important determinant of invasion success for deliberate releases of mosquitoes; severe fitness costs can prevent transinfected Wolbachia from establishing even when reproductive effects are strong (98), whereas positive fitness effects increase the rates of establishment and spread of Wolbachia. Laboratory experiments indicate that native Wolbachia infections can provide fitness benefits such as fecundity benefits or changes in life cycles (71, 158) as well as virus protection. As noted above, positive effects—largely uncharacterized—can explain the persistence of non-CI Wolbachia in natural populations and the spread of CI-causing Wolbachia from low frequencies (72, 90). However, the overall impact of Wolbachia infections on host fitness is often poorly understood for natural infections, particularly under field conditions. Fitness effects observed in laboratory studies are often insufficient to explain the dynamics of Wolbachia in natural populations (71, 90); thus, many fitness effects are likely undescribed.

Wolbachia introduced experimentally into mosquitoes for disease suppression has diverse effects on fitness, with a mix of costs and benefits depending on the variant (Figure 2). Fitness effects in novel hosts can be hard to predict since densities and tissue distributions can change dramatically upon interspecific transfer. For example, the wAlbA/wAlbB superinfection in Ae. albopictus provides an overall fitness benefit, but when wAlbB alone is transferred to Ae. aegypti it induces fitness costs (Figure 2a). Experimentally generated Wolbachia infections in Ae. aegypti tend to affect fertility most severely, while effects on other traits are less clear (Figure 2b). Fitness effects depend strongly on the environmental context; costs are often not apparent in standard laboratory assays but can be exacerbated under stressful conditions such as when larvae are held under competitive conditions (115) or when adults or eggs are aged (88, 154).

Evaluating the fitness of Wolbachia-infected individuals is challenging because confounding factors affect experimental outcomes. Yet fitness parameters, often from preliminary studies, are used in mathematical models aimed at informing the choice of Wolbachia variants for disease control (152). For variants introduced into Ae. aegypti, studies of the same trait sometimes produce conflicting results (Supplemental Data Set 1). Most studies compare the fitness of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected populations by removing Wolbachia with tetracycline treatment, but this can cause off-target effects (77). Fitness effects can also vary depending on genomic background (108) and may change over time with laboratory culture (22, 87). In Ae. aegypti, fitness can differ between replicate populations after only a few generations, making it difficult to attribute fitness effects to Wolbachia infection alone, particularly if lines differ in inbreeding levels (116). Most studies measure fitness under laboratory conditions, so traits important for disease control, such as host-seeking behavior and biting ability, are rarely measured under realistic contexts.

Fitness effects on mating are particularly important when considering releases aimed at population suppression. Most data, including those from experiments on Ae. aegypti in tent enclosures (125), suggest that the mating competitiveness of Aedes males is unaffected by Wolbachia (Supplemental Data Set 1). There is also no evidence for Wolbachia-related assortative mating in Ae. aegypti (19) or Culex pipiens (10). However, Wolbachia-related assortative mating has been documented in other systems including D. melanogaster (69) and spider mites (144).

From a disease perspective, a key question is whether virus blocking is mechanistically associated with deleterious fitness effects (making population replacement harder for variants with strong virus blocking). In Ae. aegypti, transinfected wMelPop and wAu provide strong blocking (4, 146) but induce large fitness costs. In Drosophila, infections providing strong blocking tend to occur at a higher density and have higher fitness costs (29, 84). But there are exceptions to these patterns; wAu has a high density and strong virus protection with little impact on fitness in D. simulans (85), suggesting that virus blocking and fitness costs are not always linked. Further, multiple strains present in the same individual might impose additional fitness costs but also additional blocking potential. In Ae. aegypti doubly infected with wMel and wAlbB, extra protection seems to be provided without additional fitness costs (67).

Theory predicts that Wolbachia should evolve toward mutualism or at least toward reduced costs (137). Evolutionary changes leading to increased fitness have been documented for D. simulans infected with wRi (147), and laboratory selection can produce rapid changes in Wolbachia-associated phenotypic effects on host fitness (29) and nucleus-associated changes in Wolbachia effects on host fitness (23). A recently discovered Wolbachia strain limited to adult females (109) may also reflect ongoing Wolbachia and host evolution to reduce host costs but ensure maternal transmission. It is not clear whether these types of evolutionary shifts in fitness influence virus blocking by Wolbachia.

4. ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS ON WOLBACHIA

Frequencies of Wolbachia infections in natural populations are highly variable (121). In some insects, such as Ae. albopictus, Wolbachia infections are nearly fixed throughout their distribution (6), while in others there are strong geographic or climatic patterns. Frequencies of Wolbachia infection can vary clinally; for example, in Drosophila melanogaster (71) and Curculio sikkimensis (134) frequencies increase at lower latitudes. Similar patterns are observed across entire insect orders such as Lepidoptera (2), but patterns across arthropods as a whole are less clear (28). Wolbachia densities and frequencies can differ between locations (30, 136) and vary seasonally (130). These patterns may reflect environment-dependent selection on Wolbachia infections but could also result from direct environmental effects on Wolbachia or its maternal transmission.

Several environment-dependent fitness effects of Wolbachia have been documented. Wolbachia infections often reduce host viability during periods of dormancy such as in Ae. aegypti (88, 154) and D. melanogaster (71); this may reflect Wolbachia replication while the host is inactive. In Ae. albopictus, Wolbachia shifts from beneficial to detrimental when larvae are reared under nutritional stress (43). Nutrition also modulates the effects of Wolbachia on Drosophila, with both costs and benefits to fecundity depending on diet (17, 106). Temperature strongly influences fitness effects; the severity of life shortening by wMelPop in D. melanogaster is increased at higher temperatures (108), while Wolbachia can influence thermal tolerance in both natural (46) and transinfected (117) hosts.

Environmental conditions associated with temperature and nutrition influence the reproductive effects of Wolbachia and may explain differences seen between field and laboratory populations (60). High temperatures can reduce rates of maternal transmission, CI, and male killing, with effects depending on host species (32, 77) and Wolbachia variants (118). In Ae. aegypti, wAu is more stable than wMel under heat stress even though these variants are derived from closely related hosts (4). Temperature effects could influence the ability of Wolbachia transinfections to invade and persist in Ae. aegypti populations (117), but this will depend on the proportion of breeding sites exposed to high temperatures, which is likely to be highly variable. Critically, high temperatures could also influence viral disease blocking by Wolbachia, given the link between Wolbachia density and the strength of blocking dengue (80). There is some evidence that environmental conditions modulate Wolbachia-mediated pathogen blocking in other systems (21, 94). Simulated data for Malaysia suggest that high temperatures will reduce Wolbachia-mediated virus blocking (W.A. Nazni, unpublished data), but there is no evidence that wMel has a reduced ability to block viruses under warm field conditions in Vietnam (25). Besides temperature and nutrition, wMel Wolbachia density and host reproductive effects in Ae. aegypti are affected by low levels of antibiotics likely to be encountered in some mosquito breeding sites, although wAlbB appears unaffected by low levels of antibiotics (37).

5. EFFECTS OF HOST VARIATION

Components of hosts that need to be considered in Wolbachia releases include host nuclear genomes, other Wolbachia variants, other bacteria, and mtDNA. Pesticide resistance in release stocks should ideally match levels in target populations. If resistance levels are too low, field pesticide use can result in the failure of releases. This occurred in an area of Rio de Janeiro where Wolbachia releases led to intermediate frequencies of wMel before the infection frequency dropped due to low levels of pyrethroid resistance (42). Because resistance alleles carry fitness costs, resistance decreased while release stocks were being developed. Field fitness may also be reduced through genetic adaptation to artificial rearing conditions, a phenomenon common to many reared insects, including mosquitoes (56). Maintaining the quality of release stocks is a key component for successful sterile release programs (129).

The impact of other Wolbachia infections carried by a host needs to be considered. For instance, Ae. albopictus generally carries wAlbA and wAlbB, so triple infections are needed for population replacement, whereas triply infected strains or novel strains with wAlbA and wAlbB removed but carrying another variant added are needed for suppression (20). Population replacement depends on the direction and strength of incompatibility. With bidirectional incompatibility, replacement will generally be difficult because the unstable equilibrium is likely to be near 50% (58). Such infections are unlikely to spread because they are easily stopped by barriers to dispersal and density-dependent effects that slow mosquito development rates (49). Unidirectional incompatibility facilitates invasion because the unstable point is typically lower.

In Ae. aegypti, natural Wolbachia infections are absent or at least geographically restricted. A recent global survey did not detect natural Wolbachia infections (44), but some studies claim rare natural Wolbachia in some Ae. aegypti populations (53, 73). These studies are limited mostly to molecular detection, so it is unclear whether these infections could influence invasion of a CI-causing variant. However, it is important to monitor target release areas for natural Wolbachia infections.

Apart from native Wolbachia, interactions with other endosymbionts and the complex mosquito microbiome (53) could influence host fitness and indirectly affect Wolbachia invasion. Laboratory studies suggest that Wolbachia may substantially alter the gut microbiome in D. melanogaster even though Wolbachia is absent from the gut (127). However, in field populations of Ae. aegypti, wMel shows relatively small effects on the microbiome of adults and none on larvae (11).

As Wolbachia invades, it may also introduce novel mtDNA variants (47, 64, 133, 143), so mtDNA–Wolbachia interactions may be relevant. Comparative genomics of mtDNA and Wolbachia within and between hosts can identify and help date horizontal or introgressive transfer of Wolbachia (31, 110, 140). There is no evidence for common horizontal transfer of Wolbachia in mosquitoes (9), and we are unaware of mtDNA–Wolbachia interactions that influence host or Wolbachia phenotypes, but this needs further testing.

6. POPULATION REPLACEMENT WITH WOLBACHIA

6.1. Wolbachia Invasion and Spread in Nature

Given the high incidence of Wolbachia across insects and mites, the bacterium is clearly successful in spreading within and among natural populations and species. If Wolbachia causes intense CI, local spread will be rapid once the frequency appreciably exceeds the unstable threshold frequency, expected to be near zero for natural infections but possibly 10–30% for many transinfections. The ultimate rapid local spread reflects the massive advantage that infected females have over uninfected females once infected males become common.

Only a few natural Wolbachia invasions have been documented. This is unsurprising since most cases of horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in nature are expected to fail and successful spatial spread can be rapid (72). Despite a few exceptions (63, 76), intraspecific horizontal transmission seems generally rare (31, 110, 140). Empirical examples of spatial spread occur with CI (12, 141), with male killing (61), and with no reproductive manipulation (72). Wolbachia variants that cause strong CI are usually at high frequencies in populations (71), whereas male-killing Wolbachia variants tend to persist at lower frequencies, but there are exceptions (27). Wolbachia spread can be blocked by other Wolbachia. In Cx. pipiens in Tunisia, two Wolbachia variants show clear spatial separation, with a sharp contact zone that has been stable for seven years; one variant causes strong CI in crosses with females carrying the other variant, while the reciprocal cross produces CI in only some crosses (10). As discussed in Section 6.2.4, dispersal barriers and spatial variation in population density probably contribute to contact zone stability. Stable but variable infection frequencies across populations also occur in Drosophila (71).

6.1.1. Field introductions.

In Ae. aegypti, successful field invasion of transinfections has been achieved for two variants, wMel and wAlbB (Table 1). Both variants cause strong CI in Ae. aegypti, and invasion was first established in small cages (146, 151). An additional variant, wMelPop, invaded field cages (146) but did not successfully invade field populations, likely because of strong deleterious fitness effects (98, 153).

For wMel released in northern Australia, infection frequencies appear relatively stable after invasion (54, 102), although infection frequencies decreased in one area of Cairns following invasion, possibly because the release area was too small (122). High levels of maternal transmission have also been maintained in the field; however, one case of nontransmission has been detected (123). wMel has maintained its ability to block dengue virus after one year in the field (40), but its effects on disease transmission will need to be monitored in case changes in bacterial density or host genomic background weaken virus suppression (114). This might occur if attenuation of negative fitness effects associated with Wolbachia, as occurred in D. simulans (147), is correlated with reduced virus blocking.

6.1.2. Multiple infections.

In addition to the release of hosts carrying one Wolbachia variant for population replacement or suppression, hosts carrying multiple Wolbachia variants are now being released (Table 1). Multiple infections may be useful in several contexts. First, a multiply infected host may be used to invade populations already naturally infected by one Wolbachia variant. In cases in which males carrying each variant cause CI with uninfected females and with females carrying the alternative variant, males carrying both variants are typically incompatible with females carrying only one variant, whereas females carrying both variants are compatible with doubly and singly infected males (58). This pattern is seen when wRi from D. simulans is added to the natural infections wAlbA and wAlbB in Ae. albopictus (41). Second, double infections can be used after successful introduction of a singly infected strain fails to achieve its objectives, such as when it no longer effectively blocks arbovirus transmission (114).

Although many insects carry multiple Wolbachia variants [e.g., Rhagoletis cerasi carries at least five (7)], laboratory production of multiply infected strains capable of invading natural populations is not straightforward. In Ae. albopictus, which is usually naturally infected by wAlbA and wAlbB, adding wMel produces a new strain that shows self-incompatibility likely because one of the native Wolbachia is lost from ovaries (5). By contrast, a strain of Ae. aegypti coinfected with wMel and wAlbB appears relatively stable and self-compatible, and its males are incompatible with females singly infected with either Wolbachia variant (67). It remains to be seen whether multivariant transinfections are stable (and stably transmitted) in nature, given that natural double-infected species show occasional infection loss under field conditions. For instance, Ae. albopictus often exhibits a low frequency of singly infected or uninfected individuals in nature plus a high level of variation in relative densities of different Wolbachia variants (1). Wolbachia density variation is probably associated with environmental conditions, as discussed above.

6.1.3. Complications.

Wolbachia invasion has so far relied largely on releases in target areas with only low-rise buildings (55, 102, 122), but in many landscapes, building height varies (36), adding a vertical component to host distribution. Wolbachia releases must consider the effects of a three-dimensional urban landscape structure on the distribution of hosts in a target area. Nevertheless, in Ae. aegypti, invasion of a wAlbB transinfection has succeeded in a relatively small area consisting of 18-story buildings (W.A. Nazni, unpublished data) likely because mosquito movement occurs primarily within rather than across buildings (66).

6.2. Theory Concerning Wave Initiation, Speed, Width, and Stopping with Bistable Dynamics

We focus on idealized models describing the spatial spread of transinfections that produce strong CI but induce fitness costs that lead to bistability. In these simple models the position of the unstable infection frequency, denoted , is determined by the rate of maternal transmission, fitness effects, and CI intensity (26, 58). More realistic models involving factors such as age structure (138), population dynamics (49), and sex-dependent effects cannot be fully described through the use of infection frequencies only. Nevertheless, idealized models that track temporal and spatial dynamics of infection frequencies suffice to illustrate key theoretical ideas (15) and seem to provide a useful first approximation for understanding actual transinfection releases (122). Easily described results are generally available only for continuous-time, continuous-space approximations. Hence, we focus on these results for their heuristic value but indicate how less idealized approximations that account for more realistic dispersal and local frequency dynamics alter the simplest predictions (139).

Although stochastic effects are needed to understand local spread of rare bistable variants (65) or spatial spread beyond barriers that would be expected to halt spread (48), we focus on deterministic models for simplicity.

6.2.1. Wave initiation.

In an isolated population, establishment of a transinfection with bistable dynamics requires that releases produce a transinfection frequency that exceeds the unstable point, . To replace mosquito populations in large continuous landscapes, release programs must introduce the transinfection in an area that is large enough to persist in the face of migration of uninfected individuals from the surrounding habitat. Barton and Turelli (15, 139) provide approximations for the minimum size of the release areas, and those predictions seem consistent with initial empirical releases (122). There are two key results. First, spatial spread can occur only if the unstable point, , is sufficiently small, with a maximum near 0.5. Second, the minimum size of a release area depends on both and the average dispersal distance of the host, denoted σ. As discussed below, wave speed in a homogeneous environment is roughly proportional to and this difference also governs the sensitivity of spread to environmental heterogeneity. Hence, transinfections should ideally have for spread. When this is satisfied, a fairly robust prediction is that release areas with a radius of at least 4σ should suffice to initiate spatial spread. For a vector such as Ae. aegypti with σ on the order of 100 m, release areas of roughly 0.5 km2 should suffice. When more realistic dispersal models that are long tailed relative to a Gaussian (i.e., most individuals move short distances but a few go relatively far) are analyzed, the minimal release area is smaller (139).

Data from 2013 releases of wMel-transinfected Ae. aegypti in Cairns seem broadly consistent with these predictions. Releases in areas of roughly 1 km2 and 0.5 km2 led to spatial spread of the transinfection, but a release in a much smaller area (0.1 km2) seemed to be collapsing before additional releases were undertaken. Releases across large areas require more resources depending on mosquito densities. For instance, invasion of an area with approximately 600 houses and an estimated density of 5–10 female mosquitoes per house was successful, after releases of approximately 10 wMel females per house per week across 10 weeks (112). Releases in areas with strong density dependence in breeding sites are also predicted to occur much more slowly because of heterogeneity in mosquito fitness (49).

6.2.2. Wave speed.

If we assume complete CI, so that all embryos produced from incompatible matings die, an idealized model of spatial spread with bistable dynamics in a homogeneous environment predicts that the transinfection will spread in all directions at a speed of

| 1. |

per generation, where is the unstable equilibrium and σ is the dispersal distance per generation (15). If CI is incomplete, wave speed is multiplied by , where sh is the relative reduction in embryo viability induced by CI. Less idealized models, with fast local dynamics and long-tailed dispersal, predict slower spread, with plausible reductions on the order of 20–30% (139). Note that if σ is approximately 100 m and is approximately 0.25, Equation 1 predicts spread at approximately 25 m per generation. Hence, with approximately 10 generations per year, we expect the transinfection to spread at roughly 250 m/year. Accounting for more realistic local dynamics and dispersal reduces the prediction to roughly 175–200 m/year. Note that Equation 1 predicts that wave speed should be relatively insensitive to slight decreases in fitness costs. For instance, decreasing fitness costs so that is approximately 0.05 rather than 0.25 would less than double predicted speed.

In the only field releases yet analyzed, wMel-infected Ae. aegypti spread from two areas of Cairns at roughly 110 and 180 m/year (122). These data are broadly consistent with our approximations for bistable waves but orders of magnitude slower than the rates of spatial spread for natural Wolbachia infections in D. simulans (72) and R. cerasi (12) despite comparable dispersal behaviors of the dipteran hosts (122). Any factors that reduce dispersal, such as size-reducing high larval densities or increased adult densities associated with favorable habitats, will slow wave speed. A critical empirical question is whether natural populations of Ae. aegypti and other vectors are sufficiently homogeneous for Equation 1 to provide a useful approximation. Monitoring data from recent urban releases will determine the robustness of the apparent agreement of Equation 1 with field data from Cairns (122).

6.2.3. Wave width provides an estimate of average dispersal.

The explicit traveling-wave approximation that generates Equation 1 also provides a simple description for the shape of the advancing wave. Defining wave width as the inverse of the maximum slope of infection frequencies (38), both the simplest models and more realistic models predict that the traveling wave has a width of roughly (139)

| 2. |

which becomes 4σ with complete CI, as in Ae. aegypti. From the shape of the wave, we expect infection frequencies to increase from approximately 0.18 to 0.82 over 3σ, with complete CI. This relationship allows us to approximate average dispersal in the field in locations where successful releases are undertaken. Because wave speed and minimal release areas depend on σ, initial estimates can inform future releases in comparable landscapes.

6.2.4. Wave stopping.

In addition to traveling much more slowly than natural Wolbachia infections, for which we expect F(1 − μ) > 1 and , the spread of bistable transinfections is readily stopped by barriers to dispersal that effectively reduce migration in the direction of wave movement (14, 15). Conversely, spread is expected to accelerate from high-density to low-density locations because of asymmetry in migration. Once the unstable point approaches 0.3, spreading waves are predicted to be stopped by even relatively minor barriers, for instance, an increase in population density on the order of 2 or 3. Spreading into an area of higher population density is analogous to crossing a barrier that reduces migration (15). In Gordonvale, Australia, one of the initial release sites for wMel-infected Ae. aegypti (55), a highway that interrupted housing for roughly 100 m sufficed to block the spread of wMel for several years (139). The effects of roads on movement have also been documented through mark-release experiments (119) and through genetic relatedness comparisons (123). Vegetation may also act as a barrier to Ae. aegypti (122). High-density populations of conspecifics should prevent the spread of Wolbachia with deleterious effects due to density effects.

6.2.5. Release strategies and contribution of slow transinfection spread to area-wide control.

Turelli & Barton (139) address how to most efficiently transform large areas and the potential contributions of even slow spread as predicted by Equation 1 and its refinements. Given the tendency for transinfections to move down density gradients, initial releases should target areas of greatest disease vector density, which also tend to be hot spots of disease incidence. Even slow spatial spread of transinfections on the order of 10–20 m/month will lead to area-wide coverage over a few years, with releases covering only 20–30% of the target area. However, this idealized prediction ignores the practical problem that releases must be carried out in all areas that are isolated by effective barriers to dispersal. As field releases continue, we expect more useful predictions about barriers that stop transinfection spread (122).

7. VECTOR POPULATION SUPPRESSION WITH WOLBACHIA

The use of CI to suppress vector populations was initiated in successful local field trials by Laven (75) and is analogous to the release of sterile males (sterile insect technique), which has been effective in area-wide control of the screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) and the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) (3, 70). Recently, CI-based suppression has been attempted in small areas around Guangzhou, China, with successful vector population reductions of 95% or higher (157). Varying levels of suppression in other areas have also been achieved (Table 1). Unlike population replacement, suppression requires ongoing releases and is subject to reinvasion of disease vectors through long-distance dispersal, although it should be possible to reduce release rates once initial suppression has been successful (157).

Population suppression with Wolbachia depends on releasing only male hosts carrying Wolbachia variants that cause strong CI. The transinfected males must successfully compete with males from the natural target population for mates. Suppression is facilitated by the absence of multiple mating in host females (especially if the sperm from uninfected males are relatively more competitive), the absence of assortative mating associated with Wolbachia, and ecological factors that help released males find native females.

Data from natural populations suggest that Wolbachia rarely influences mating success, with a few exceptions (124). In transinfected populations, limited data indicate minimal effects on male mating success, as noted previously (see Supplemental Data Set 1). Assortative mating involving transinfections has been rarely tested. In Ae. aegypti, mating appears random with respect to Wolbachia infection, but the success of releases can be influenced by other forms of assortative mating. For instance, laboratory experiments indicate assortative mating for size (19), with small females preferentially mating with small males. This can influence field success of released males, which are typically larger than field mosquitoes and have a much greater variance in size.

Insecticide resistance may influence the success of released males, particularly when fogging targets adults. Other deleterious effects associated with inbreeding and adult male food might influence the success of infected males competing with males reared in nature. Although the impact of inbreeding on competitive male performance has not been rigorously tested, it is expected to decrease male fitness (116). Deleterious effects from feeding on particular blood sources might also carry over to the fitness of offspring (105) and are worth exploring further for effects on male mating success.

For releases to suppress populations, infected released males must find wild-type females. Releasing sufficient numbers of males at the right place for Ae. aegypti can be challenging because breeding sites producing males are often cryptic (e.g., 13). It may be possible to target the distribution of human hosts, which attract both male and female Ae. aegypti (50), but this remains to be tested. When suppression releases take place in complex urban landscapes with a mix of high-and low-rise buildings, different release strategies may be required. For high-rise buildings, males may need to be released on multiple floors, whereas dispersal of mosquitoes along thoroughfares by hand (157) or through engineered systems (https://debug.com/) may be adequate for only low-rise buildings. Suppression might still be achieved if enough males are released, even when there is a low likelihood of males effectively reaching mating sites, particularly given increasingly efficient production, sexing, and release technology (e.g., 156). However, a high density of (nonbiting) males might be unacceptable to residents when releases continue for some time, highlighting the need for ongoing community engagement (Figure 1).

8. CONCLUSIONS

Understanding the dynamics of natural Wolbachia infections has helped researchers identify factors that enhance and retard the rate of spread, inspired models to predict Wolbachia spread, and provided information on the likely long-term stability of both the infections and their phenotypic effects (18). Population studies of Aedes spp. have highlighted some of the challenges in using Wolbachia technology, including the heterogeneous distribution of breeding sites, the ability of some mosquitoes to disperse across large distances, the high levels of inbreeding depression, and the evolutionary potential to rapidly evolve pesticide resistance. The long-term stability of Wolbachia-based replacement interventions will depend on the ability of Wolbachia to continue to reduce local viral transmission under changing environmental conditions, and on the maintenance of a high frequency of Wolbachia in populations; both factors require ongoing monitoring. Suppression strategies require efficient ways to distribute infected males to areas where receptive females are common and to maintain highly competitive stocks for ongoing releases.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY POINTS.

Fitness effects associated with transinfections are variable, often measured under contrived circumstances poorly linked to field conditions, and applied arbitrarily in models.

Environmental effects need to be considered in release success and impact. As shown by natural infections, there is potential for Wolbachia–environment–host-genome interactions.

There is a contrast between natural (mutualistic) and transinfection (deleterious) invasion dynamics that makes the rapid spread observed for some natural infections implausible for transinfections.

Virus blocking is critical in population replacement releases, but host benefits associated with virus blocking by natural Wolbachia infections are poorly documented (and may not exist).

Theory should be expanded to incorporate three-dimensional landscapes and produce field-validated predictors of barriers likely to impede or stop spatial spread.

Releases must be followed by ongoing monitoring, given there is uncertainty around long-term outcomes including the stability of virus blocking and population replacement.

Artificial rearing conditions including surrogate blood sources may have negative effects on the fitness of released mosquitoes.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Is there a trade-off between virus blocking and host fitness effects? This requires assessing trade-offs within and between multiple Wolbachia variants and host backgrounds.

Which Wolbachia variants are appropriate for different contexts? Field comparison of multiple variants is needed to assess invasion potential and virus blocking.

Are simple models for spatial spread applicable to different contexts? Models have been developed and tested near Cairns, Australia, but not in complex tropical environments.

Can we develop useful predictions to characterize barriers likely to halt spread?

What is the stability of transinfections and their impact on natural populations? Monitoring long-term stability of Wolbachia frequencies in different areas is required along with monitoring Wolbachia titer, virus blocking, and host fitness effects.

Do disease viruses evolve in response to Wolbachia? This requires monitoring viruses in endemic disease areas and assessing evolutionary forces affecting viral transmission through mosquito and human hosts.

How can genetic quality of mosquito release stocks be maintained? The effects of evolutionary adaptation to mass production conditions on field performance, particularly mating performance and human-host finding, need to be further assessed.

Which environmental conditions are optimal for mosquito releases? The impact of different blood sources, rearing conditions, and feeding methods needs to be assessed on release stocks, particularly for suppression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.A.H. is supported by a program grant (1132421) and fellowship (1118640) from the National Health and Medical Research Council and receives funding from the Wellcome Trust for Wolbachia mosquito research. M.T. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM104325). The authors thank Penny Hancock, Brandon Cooper, John Jaenike, and Gabriela Gomes for comments on an earlier draft of this review.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Ahantarig A, Trinachartvanit W, Kittayapong P. 2008. Relative Wolbachia density of field-collected Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in Thailand. J. Vector Ecol 33:173–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed MZ, Araujo-Jnr EV, Welch JJ, Kawahara AY. 2015. Wolbachia in butterflies and moths: geographic structure in infection frequency. Front. Zool 12:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alphey L, Benedict M, Bellini R, Clark GG, Dame DA, et al. 2010. Sterile-insect methods for control of mosquito-borne diseases: an analysis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 10:295–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ant TH, Herd CS, Geoghegan V, Hoffmann AA, Sinkins SP. 2018. The Wolbachia strain wAu provides highly efficient virus transmission blocking in Aedes aegypti. PLOS Pathog 14:e1006815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ant TH, Sinkins SP. 2018. A Wolbachia triple-strain infection generates self-incompatibility in Aedes albopictus and transmission instability in Aedes aegypti. Parasites Vectors 11:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armbruster P, Damsky WE Jr., Giordano R, Birungi J, Munstermann LE, Conn JE. 2003. Infection of New- and Old-World Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) by the intracellular parasite Wolbachia: implications for host mitochondrial DNA evolution. J. Med. Entomol 40:356–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthofer W, Riegler M, Schneider D, Krammer M, Miller WJ, Stauffer C. 2009. Hidden Wolbachia diversity in field populations of the European cherry fruit fly, Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera, Tephritidae). Mol. Ecol 18:3816–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asselin AK, Villegas-Ospina S, Hoffmann AA, Brownlie JC, Johnson KN. 2019. Contrasting patterns of virus protection and functional incompatibility genes in two conspecific Wolbachia strains from Drosophila pandora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 85:e02290–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atyame CM, Delsuc F, Pasteur N, Weill M, Duron O. 2011. Diversification of Wolbachia endosymbiont in the Culex pipiens mosquito. Mol. Biol. Evol 28:2761–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atyame CM, Labbe P, Rousset F, Beji M, Makoundou P, et al. 2015. Stable coexistence of incompatible Wolbachia along a narrow contact zone in mosquito field populations. Mol. Ecol 24:508–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audsley MD, Seleznev A, Joubert DA, Woolfit M, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. 2018. Wolbachia infection alters the relative abundance of resident bacteria in adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, but not larvae. Mol. Ecol 27:297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakovic V, Schebeck M, Telschow A, Stauffer C, Schuler H. 2018. Spatial spread of Wolbachia in Rhagoletis cerasi populations. Biol. Lett 14:20180161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrera R, Amador M, Diaz A, Smith J, Munoz-Jordan J, Rosario Y. 2008. Unusual productivity of Aedes aegypti in septic tanks and its implications for dengue control. Med. Vet. Entomol 22:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton NH. 1979. The dynamics of hybrid zones. Heredity 43:341–59 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton NH, Turelli M. 2011. Spatial waves of advance with bistable dynamics: cytoplasmic and genetic analogues of Allee effects. Am. Nat 178:E48–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bian GW, Zhou GL, Lu P, Xi ZY. 2013. Replacing a native Wolbachia with a novel strain results in an increase in endosymbiont load and resistance to dengue virus in a mosquito vector. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 7:e2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownlie JC, Cass BN, Riegler M, Witsenburg JJ, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, et al. 2009. Evidence for metabolic provisioning by a common invertebrate endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during periods of nutritional stress. PLOS Pathog 5:e1000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bull JJ, Turelli M. 2013. Wolbachia versus dengue: evolutionary forecasts. Evol. Med. Public Health 1:197–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callahan AG, Ross PA, Hoffmann AA. 2018. Small females prefer small males: size assortative mating in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors 11:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvitti M, Moretti R, Lampazzi E, Bellini R, Dobson SL. 2010. Characterization of a new Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Wolbachia pipientis (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) symbiotic association generated by artificial transfer of the wPip strain from Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol 47:179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caragata EP, Rancès E, Hedges LM, Gofton AW, Johnson KN, et al. 2013. Dietary cholesterol modulates pathogen blocking by Wolbachia. PLOS Pathog 9:e1003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrington LB, Hoffmann AA, Weeks AR. 2010. Monitoring long-term evolutionary changes following Wolbachia introduction into a novel host: the Wolbachia popcorn infection in Drosophila simulans. Proc. R. Soc. B 277:2059–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrington LB, Leslie J, Weeks AR, Hoffmann AA. 2009. The popcorn Wolbachia infection of Drosophila melanogaster: Can selection alter Wolbachia longevity effects? Evolution 63:2648–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrington LB, Lipkowitz JR, Hoffmann AA, Turelli M. 2011. A re-examination of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in California Drosophila simulans. PLOS ONE 6:e22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrington LB, Tran BCN, Le NTH, Luong TTH, Nguyen TT, et al. 2018. Field and clinically derived estimates of Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus transmission potential in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PNAS 115:361–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caspari E, Watson GS. 1959. On the evolutionary importance of cytoplasmic sterility in mosquitos. Evolution 13:568–70 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlat S, Hornett EA, Dyson EA, Ho PP, Loc NT, et al. 2005. Prevalence and penetrance variation of male-killing Wolbachia across Indo-Pacific populations of the butterfly Hypolimnas bolina. Mol. Ecol 14:3525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlesworth J, Weinert LA, Araujo EV Jr., Welch JJ. 2019. Wolbachia, Cardinium and climate: an analysis of global data. Biol. Lett 15:20190273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chrostek E, Teixeira L. 2015. Mutualism breakdown by amplification of Wolbachia genes. PLOS Biol 13:e1002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper BS, Ginsberg PS, Turelli M, Matute DR. 2017. Wolbachia in the Drosophila yakuba complex: pervasive frequency variation and weak cytoplasmic incompatibility, but no apparent effect on reproductive isolation. Genetics 205:333–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper BS, Vanderpool D, Conner WR, Matute DR, Turelli M. 2019. Wolbachia acquisition by Drosophila yakuba-clade hosts and transfer of incompatibility loci between distantly related Wolbachia. Genetics 212:1399–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbin C, Heyworth ER, Ferrari J, Hurst GD. 2017. Heritable symbionts in a world of varying temperature. Heredity 118:10–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtis C, Brooks G, Ansari M, Grover K, Krishnamurthy B, et al. 1982. A field trial on control of Culex quinquefasciatus by release of males of a strain integrating cytoplasmic incompatibility and a translocation. Entomol. Exp. Appl 31:181–90 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dias NP, Zotti MJ, Montoya P, Carvalho IR, Nava DE. 2018. Fruit fly management research: a systematic review of monitoring and control tactics in the world. Crop Prot 112:187–200 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodson B, Hughes G, Paul O, Matacchiero A, Kramer L, Rasgon JL. 2014. Wolbachia enhances West Nile virus (WNV) infection in the mosquito Culex tarsalis. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 8:e2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutra HLC, dos Santos LMB, Caragata EP, Silva JBL, Villela DAM, et al. 2015. From lab to field: the influence of urban landscapes on the invasive potential of Wolbachia in Brazilian Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 9:e0003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endersby-Harshman NM, Axford JK, Hoffmann AA. 2019. Environmental concentrations of antibiotics may diminish Wolbachia infections in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol 56:1078–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endler JA. 1977. Geographic Variation, Speciation, and Clines Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferguson NM, Kien DTH, Clapham H, Aguas R, Trung VT, et al. 2015. Modeling the impact on virus transmission of Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus infection of Aedes aegypti. Sci. Transl. Med 7:279ra37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frentiu FD, Zakir T, Walker T, Popovici J, Pyke AT, et al. 2014. Limited dengue virus replication in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 8:e2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu YQ, Gavotte L, Mercer DR, Dobson SL. 2010. Artificial triple Wolbachia infection in Aedes albopictus yields a new pattern of unidirectional cytoplasmic incompatibility. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 76:5887–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia GdA, Sylvestre G, Aguiar R, da Costa GB, Martins AJ, et al. 2019. Matching the genetics of released and local Aedes aegypti populations is critical to assure Wolbachia invasion. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 13:e0007023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gavotte L, Mercer DR, Stoeckle JJ, Dobson SL. 2010. Costs and benefits of Wolbachia infection in immature Aedes albopictus depend upon sex and competition level. J. Invertebr. Pathol 105:341–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gloria-Soria A, Chiodo TG, Powell JR. 2018. Lack of evidence for natural Wolbachia infections in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol 55:1354–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham RI, Grzywacz D, Mushobozi WL, Wilson K. 2012. Wolbachia in a major African crop pest increases susceptibility to viral disease rather than protects. Ecol. Lett 15:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruntenko NE, Ilinsky YY, Adonyeva NV, Burdina EV, Bykov RA, et al. 2017. Various Wolbachia genotypes differently influence host Drosophila dopamine metabolism and survival under heat stress conditions. BMC Evol. Biol 17:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hale LR, Hoffmann AA. 1990. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and cytoplasmic incompatibility in natural populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 44:1383–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hancock PA, Godfray HCJ. 2012. Modelling the spread of Wolbachia in spatially heterogeneous environments. J. R. Soc. Interface 9:3045–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hancock PA, White VL, Callahan AG, Godfray CHJ, Hoffmann AA, Ritchie SA. 2016. Density-dependent population dynamics in Aedes aegypti slow the spread of wMel Wolbachia. J. Appl. Ecol 53:785–93 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartberg W 1971. Observations on the mating behaviour of Aedes aegypti in nature. Bull. World Health Organ 45:847–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haygood R, Turelli M. 2009. Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes in subdivided host populations. Evolution 63:432–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. 2008. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322:702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hegde S, Khanipov K, Albayrak L, Golovko G, Pimenova M, et al. 2018. Microbiome interaction networks and community structure from laboratory-reared and field-collected Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito vectors. Front. Microbiol 9:2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffmann AA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Callahan AG, Phillips B, Billington K, et al. 2014. Stability of the wMel Wolbachia infection following invasion into Aedes aegypti populations. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 8:e3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, et al. 2011. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476:454–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffmann AA, Ross PA. 2018. Rates and patterns of laboratory adaptation in (mostly) insects. J. Econ. Entomol 111:501–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffmann AA, Ross PA, Rašić G. 2015. Wolbachia strains for disease control: ecological and evolutionary considerations. Evol. Appl 8:751–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoffmann AA, Turelli M. 1997. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects In Influential Passengers: Microorganisms and Invertebrate Reproduction, ed. O’Neill S, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH, pp. 42–80. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffmann AA, Turelli M. 2013. Facilitating Wolbachia introductions into mosquito populations through insecticide-resistance selection. Proc. R. Soc. B 280:20130371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoffmann AA, Turelli M, Harshman LG. 1990. Factors affecting the distribution of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 126:933–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hornett EA, Charlat S, Wedell N, Jiggins CD, Hurst GDD. 2009. Rapidly shifting sex ratio across a species range. Curr. Biol 19:1628–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hughes GL, Rasgon JL. 2014. Transinfection: a method to investigate Wolbachia–host interactions and control arthropod-borne disease. Insect Mol. Biol 23:141–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huigens M, De Almeida R, Boons P, Luck R, Stouthamer R. 2004. Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogenesis–inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proc. R. Soc. B 271:509–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hurst GDD, Jiggins FM. 2005. Problems with mitochondrial DNA as a marker in population, phylogeographic and phylogenetic studies: the effects of inherited symbionts. Proc. R. Soc. B 272:1525–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jansen VAA, Turelli M, Godfray HCJ. 2008. Stochastic spread of Wolbachia. Proc. R. Soc. B 275:2769–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jasper M, Schmidt TL, Ahmad NW, Sinkins SP, Hoffmann AA. 2019. A genomic approach to inferring kinship reveals limited intergenerational dispersal in the yellow fever mosquito. Mol. Ecol. Resour 19(5):1254–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joubert DA, Walker T, Carrington LB, De Bruyne JT, Kien DHT, et al. 2016. Establishment of a Wolbachia superinfection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes as a potential approach for future resistance management. PLOS Pathog 12:e1005434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.King JG, Souto-Maior C, Sartori LM, Maciel-de-Freitas R, Gomes MGM. 2018. Variation in Wolbachia effects on Aedes mosquitoes as a determinant of invasiveness and vectorial capacity. Nat. Commun 9:1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koukou K, Pavlikaki H, Kilias G, Werren JH, Bourtzis K, Alahiotisi SN. 2006. Influence of antibiotic treatment and Wolbachia curing on sexual isolation among Drosophila melanogaster cage populations. Evolution 60:87–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krafsur E 1998. Sterile insect technique for suppressing and eradicating insect population: 55 years and counting. J. Agric. Entomol 15:303–17 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kriesner P, Conner WR, Weeks AR, Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. 2016. Persistence of a Wolbachia infection frequency cline in Drosophila melanogaster and the possible role of reproductive dormancy. Evolution 70:979–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kriesner P, Hoffmann AA, Lee SF, Turelli M, Weeks AR. 2013. Rapid sequential spread of two Wolbachia variants in Drosophila simulans. PLOS Pathog 9:e1003607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kulkarni A, Yu W, Jiang J, Sanchez C, Karna AK, et al. 2019. Wolbachia pipientis occurs in Aedes aegypti populations in New Mexico and Florida, USA. Ecol. Evol 9:6148–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laven H 1959. Speciation by cytoplasmic isolation in the Culex pipiens complex. Proc. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 24:166–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laven H 1967. Eradication of Culex pipiens fatigans through cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature 216:383–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li SJ, Ahmed MZ, Lv N, Shi PQ, Wang XM, et al. 2017. Plant-mediated horizontal transmission of Wolbachia between whiteflies. ISME J 11:1019–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y-Y, Floate K, Fields P, Pang B-P. 2014. Review of treatment methods to remove Wolbachia bacteria from arthropods. Symbiosis 62:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lindsey A, Bhattacharya T, Newton I, Hardy R. 2018. Conflict in the intracellular lives of endosymbionts and viruses: a mechanistic look at Wolbachia-mediated pathogen-blocking. Viruses 10:E141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lopez V, Cortesero AM, Poinsot D. 2018. Influence of the symbiont Wolbachia on life history traits of the cabbage root fly (Delia radicum). J. Invertebr. Pathol 158:24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu P, Bian GW, Pan XL, Xi ZY. 2012. Wolbachia induces density-dependent inhibition to dengue virus in mosquito cells. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 6:e1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mains JW, Brelsfoard CL, Crain PR, Huang YX, Dobson SL. 2013. Population impacts of Wolbachia on Aedes albopictus. Ecol. Appl 23:493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mains JW, Brelsfoard CL, Rose RI, Dobson SL. 2016. Female adult Aedes albopictus suppression by Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes. Sci. Rep 6:33846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mains JW, Kelly PH, Dobson KL, Petrie WD, Dobson SL. 2019. Localized control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Miami, FL, via inundative releases of Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol 56:1296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martinez J, Longdon B, Bauer S, Chan Y-S, Miller WJ, et al. 2014. Symbionts commonly provide broad spectrum resistance to viruses in insects: a comparative analysis of Wolbachia strains. PLOS Pathog 10:e1004369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martinez J, Ok S, Smith S, Snoeck K, Day JP, Jiggins FM. 2015. Should symbionts be nice or selfish? Antiviral effects of Wolbachia are costly but reproductive parasitism is not. PLOS Pathog 11:e1005021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martinez J, Tolosana I, Ok S, Smith S, Snoeck K, et al. 2017. Symbiont strain is the main determinant of variation in Wolbachia-mediated protection against viruses across Drosophila species. Mol. Ecol 26:4072–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McGraw EA, Merritt DJ, Droller JN, O’Neill SL. 2002. Wolbachia density and virulence attenuation after transfer into a novel host. PNAS 99:2918–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McMeniman CJ, O’Neill SL. 2010. A virulent Wolbachia infection decreases the viability of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti during periods of embryonic quiescence. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 4:e748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McNaughton D, Duong TTH. 2014. Designing a community engagement framework for a new dengue control method: a case study from central Vietnam. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 8:e2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meany MK, Conner WR, Richter SV, Bailey JA, Turelli M, Cooper BS. 2019. Loss of cytoplasmic incompatibility and minimal fecundity effects explain relatively low Wolbachia frequencies in Drosophila mauritiana. Evolution 73:1278–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu GJ, Pyke AT, et al. 2009. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139:1268–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moretti R, Yen PS, Houé V, Lampazzi E, Desiderio A, et al. 2018. Combining Wolbachia-induced sterility and virus protection to fight Aedes albopictus-borne viruses. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 12:e0006626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mousson L, Zouache K, Arias-Goeta C, Raquin V, Mavingui P, Failloux AB. 2012. The native Wolbachia symbionts limit transmission of dengue virus in Aedes albopictus. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 6:e1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Murdock CC, Blanford S, Hughes GL, Rasgon JL, Thomas MB. 2014. Temperature alters Plasmodium blocking by Wolbachia. Sci. Rep 4:3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Murray JV, Jansen CC, De Barro P. 2016. Risk associated with the release of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes into the environment in an effort to control dengue. Front. Public Health 4:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Narita S, Nomura M, Kageyama D. 2007. Naturally occurring single and double infection with Wolbachia strains in the butterfly Eurema hecabe: transmission efficiencies and population density dynamics of each Wolbachia strain. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 61:235–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.National Environment Agency. 2018. Wolbachia–Aedes mosquito suppression strategy Rep., Natl. Environ. Agency, Singapore: www.nea.gov.sg/corporate-functions/resources/research/wolbachiaaedes-mosquito-suppression-strategy [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nguyen TH, Le Nguyen H, Nguyen TY, Vu SN, Tran ND, et al. 2015. Field evaluation of the establishment potential of wMelPop Wolbachia in Australia and Vietnam for dengue control. Parasites Vectors 8:563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.O’Connor L, Plichart C, Sang AC, Brelsfoard CL, Bossin HC, Dobson SL. 2012. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a Wolbachia biopesticide: field performance and infection containment. PLOS Neglect. Trop. Dis 6:e1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]