To the Editor:

Sepsis, a life-threatening dysregulated host response to infection, is the most expensive condition treated in hospitals in the United States, responsible for upward of $23 billion in hospital costs annually (1, 2). In-hospital sepsis mortality has been decreasing over time, leading to an increasing number of survivors, many with ongoing healthcare needs after hospital discharge (3–5). Postacute care (PAC) often meets those needs through home health services, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), and long-term care hospitals (6). PAC offers the opportunity for continued functional recovery after hospital discharge and may enable patients to ultimately return home safely. In addition, there is evidence demonstrating that rehabilitation after sepsis has the potential to improve long-term mortality (7). PAC use has proliferated in the last 30 years (8) under pressure to decrease hospital length of stay and to reduce readmissions, though more recent pressure to reduce spending with value-based purchasing has slowed or, in some cases, reversed its growth (9–11). The extent of PAC use after hospitalization for sepsis is unknown. Our objective was to examine trends in use of different PAC settings after hospital admissions for sepsis in a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of discharges of Medicare beneficiaries who had been hospitalized for sepsis (diagnosis-related groups [DRGs] 870, 871, and 872) using 100% Medicare claims for hospitalization and PAC between 2011 and 2016, excluding those younger than 65 years of age, hospitalized fewer than 3 days, in a nursing home in 30 days before admission, enrolled in Medicare Advantage, or discharged to hospice or non-PAC institutional settings. DRGs were selected because they identify sepsis for payment purposes, including in bundled payment initiatives. We identified each discharge’s first posthospitalization destination and examined trends in discharge disposition over time. We stratified our analyses by use of mechanical ventilation (based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9], and ICD-10 codes [12, 13]) and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (based on revenue center codes [14]). We used multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, sex, race, year, DRG, and 31 indicators of comorbidities measured in the year before hospitalization (using data from 2010 to 2016) based on the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and then we estimated marginal predicted probabilities. The comorbidity indicators were based on diagnosis codes for the index hospitalization and any hospitalizations within the preceding 12 months, and they included diagnoses such as renal failure and malignancy. Trends were assessed using nonparametric tests with the nptrend package in the Stata statistical software (StataCorp) for unadjusted data and Wald tests for adjusted data. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Results

Of 1,640,433 hospital discharges after sepsis, 52.6% were discharged to home, 29.3% to SNFs, 13.1% to home with home health services, 2.5% to long-term care hospitals, and 2.5% to IRFs. Compared with patients discharged to home, patients discharged to PAC had longer hospital lengths of stay and more frequent mechanical ventilation and ICU stays (Table 1). Among facilities, PAC length of stay was shortest at IRFs (13.4 d) and longest at SNFs (39.8 d).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients discharged from the hospital in the study cohort

| Home (n = 862,594) | Home with Home Health (n = 214,465) | SNF (n = 480,716) | IRF (n = 41,060) | LTCH (n = 41,598) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficiary age, yr |

77.4 (7.9) | 79.7 (8.1) | 81.8 (8.2) | 78.6 (7.6) | 78.2 (8.0) | |

| Female sex, % |

51.1 | 54.9 | 59.0 | 49.7 | 51.3 | |

| Race/ethnicity, % |

||||||

| White |

85.3 | 85.3 | 85.4 | 88.0 | 73.7 | |

| Black |

7.7 | 7.8 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 16.4 | |

| Hispanic |

2.2 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 4.6 | |

| Dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, % |

16.9 | 17.9 | 34.1 | 10.6 | 30.5 | |

| Hospital length of stay, d |

4.8 (3.6) | 6.4 (4.4) | 7.9 (5.6) | 8.9 (5.9) | 10.1 (6.8) | |

| Mechanical ventilation during hospitalization, % |

3.4 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 26.9 | |

| ICU admission during hospitalization, % |

21.1 | 24.4 | 29.9 | 42.0 | 53.7 | |

| PAC length of stay, d | — | 47.5 (84.5) | 39.8 (34.3) | 13.4 (5.8) | 25.7 (19.5) | |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; IRF = inpatient rehabilitation facility; LTCH = long-term care hospital; PAC = postacute care; SNF = skilled nursing facility.

Data are mean (standard deviation [SD]) unless specified otherwise.

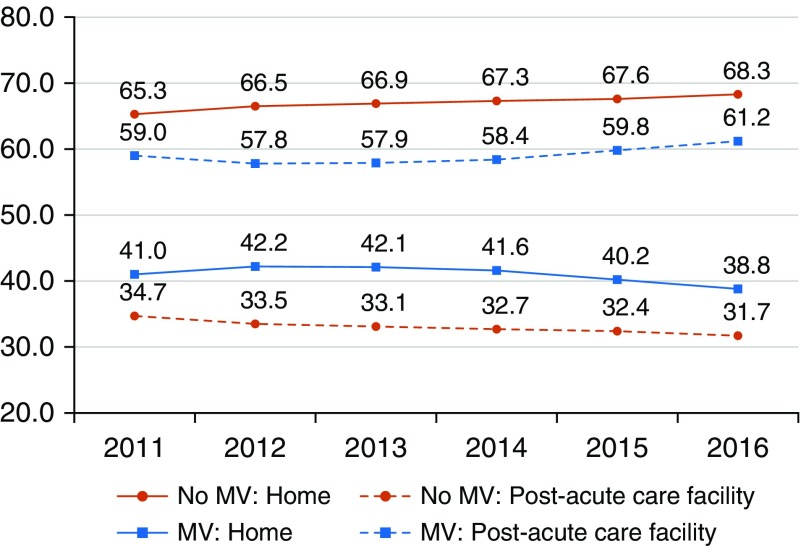

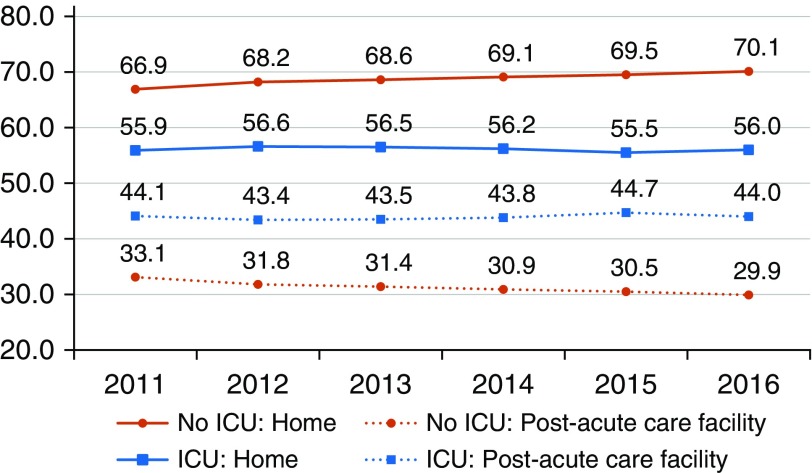

In general, there was an increase in the proportion of patients discharged to home without services, from 50.8% in 2011 to 54.1% in 2016, and a decrease in the proportion using PAC (P < 0.05 for tests of temporal trend in each setting). The reduction in PAC use was driven by fewer discharges to SNFs, from 30.8% in 2011 to 28.3% in 2016. However, the observed decline in the use of PAC was confined to patients who did not receive care in an ICU (Figures 1 and 2). Specifically, among patients who received mechanical ventilation, discharges to PAC facilities increased from 59.0% in 2011 to 61.2% in 2016. The rates were stable among patients who received care in the ICU, with more patients discharged to home than to PAC.

Figure 1.

Discharge to home or to home health compared with post–acute care facility over time, stratified by mechanical ventilation (MV). Home includes discharge to home with or without home health.

Figure 2.

Discharge to home or to home health compared with post–acute care facility over time, stratified by intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Home includes discharge to home with or without home health.

Discussion

We found that patients are commonly discharged to PAC after admissions for sepsis, and although evidence suggests that rehabilitation after sepsis may confer a long-term survival benefit (7), an increasing majority of patients were discharged directly to home, with fewer patients going to SNFs. This trend did not extend, however, to patients with mechanical ventilation or ICU stays during their hospitalization, potentially indicating that care for critically ill patients may be less responsive to payment reforms or institutional sepsis initiatives. Differences in illness severity likely explain the increased use of PAC among patients who received mechanical ventilation, but not among all patients with ICU stays.

Recent research has found that patients discharged to SNFs have lower readmission rates, albeit at higher costs, than those discharged to home with home health (15). Declining SNF use has been associated with recent payment reforms, including bundled payment initiatives and accountable care organizations, and likely reflects pressure to constrain costs under these reforms (16–18). This trend is expected to continue as more health systems work to optimize care delivery while constraining costs (19). Our findings of fewer patients being discharged to SNFs is consistent with broader national trends in PAC use and raises concerns that declining SNF use could result in higher readmission rates for patients with sepsis.

Limitations of this study include those inherent in administrative data, particularly because prior studies have shown that claims-based identification of patients with sepsis increased over time, whereas the trends are stable using electronic health records (20–22). We addressed this concern with adjustments for both administrative code (DRG) and patient comorbidities, but it remains a limitation. Given the substantial differences in the characteristics of patients discharged to different settings, we cannot directly comment on how these trends might affect patient outcomes.

In conclusion, discharge patterns have changed over time for patients after admissions for sepsis, with a trend toward decreased use of PAC, particularly SNFs, but only for patients without ICU admission or mechanical ventilation. This may reflect broader trends of constraining costs, with less elasticity for sicker patients. Discharge destination is a likely target for constraining costs after hospital discharge, driving a need to understand trade-offs in discharges to different PAC settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32 HL098054 (J.T.L.), and by NIH grant K24-AG047908 (R.M.W.).

Author Contributions: J.T.L., M.Q., and R.M.W. contributed to data acquisition and analysis. J.T.L., M.E.M., and R.M.W. contributed to study conception and design. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and agreed to manuscript submission. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torio CM, Andrews RM. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2011. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Brief 160. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013 [accessed 2019 May 8]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK169005/

- 3.Ortego A, Gaieski DF, Fuchs BD, Jones T, Halpern SD, Small DS, et al. Hospital-based acute care use in survivors of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:729–737. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, Escobar GJ, Iwashyna TJ. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones TK, Fuchs BD, Small DS, Halpern SD, Hanish A, Umscheid CA, et al. Post-acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:904–913. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-504OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao PW, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, Tseng CM, Kuo SC, Shih YN, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1003–1011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1170OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319:1616–1617. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:518–526. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1282–1289. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Evaluation of Medicare’s bundled payments initiative for medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1801569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerlin MP, Weissman GE, Wonneberger KA, Kent S, Madden V, Liu VX, et al. Validation of administrative definitions of invasive mechanical ventilation across 30 intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1548–1552. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-0953LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta AB, Walkey AJ, Curran-Everett D, Matlock D, Douglas IS. Hospital mechanical ventilation volume and patient outcomes: too much of a good thing? Crit Care Med. 2019;47:360–368. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman GE, Hubbard RA, Kohn R, Anesi GL, Manaker S, Kerlin MP, et al. Validation of an administrative definition of ICU admission using revenue center codes. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e758–e762. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M, Konetzka RT.Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, Rajkumar R, Marshall J, Tan E, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316:1267–1278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett ML, Wilcock A, McWilliams JM, Epstein AM, Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, et al. Two-year evaluation of mandatory bundled payments for joint replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:252–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809010. [Published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 380:2082.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein A, Ji Y, Mahoney N, Skinner J. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment program for lower extremity joint replacement and discharge to institutional postacute care: interim analysis of the first year of a 5-year randomized trial. JAMA. 2018;320:892–900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mechanic R. Post-acute care—the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, et al. CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009–2014. JAMA. 2017;318:1241–1249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walkey AJ, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Trends in sepsis and infection sources in the United States: a population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:216–220. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-498BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:754–761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.