Abstract

Background

This study examined the effects of gabexate mesilate on spinal nerve ligation (SNL)-induced neuropathic pain. To confirm the involvement of gabexate mesilate on neuroinflammation, we focused on the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and consequent the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were used for the study. After randomization into three groups: the sham-operation group, vehicle-treated group (administered normal saline as a control), and the gabexate group (administered gabexate mesilate 20 mg/kg), SNL was performed. At the 3rd day, mechanical allodynia was confirmed using von Frey filaments, and drugs were administered intraperitoneally daily according to the group. The paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was examined on the 3rd, 7th, and 14th day. The expressions of p65 subunit of NF-κB, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and iNOS were evaluated on the 7th and 14th day following SNL.

Results

The PWT was significantly higher in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05). The expressions of p65, proinflammatory cytokines, and iNOS significantly decreased in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05) on the 7th day. On the 14th day, the expressions of p65 and iNOS showed lower levels, but those of the proinflammatory cytokines showed no significant differences.

Conclusions

Gabexate mesilate increased PWT after SNL and attenuate the progress of mechanical allodynia. These results seem to be involved with the anti-inflammatory effect of gabexate mesilate via inhibition of NF-κB, proinflammatory cytokines, and nitric oxide.

Keywords: Analgesia, Gabexate, Hyperalgesia, Human, Inflammation, Neuralgia, NF-Kappa B, Nitric Oxide Synthase Type II, Spinal Nerves

INTRODUCTION

The progress of neuropathic pain, a refractory disease characterized by a decreased threshold to nociceptive stimuli and sensitization to innoxious stimuli, has an extremely complicated nature and needs a novel treatment with potent therapeutic effects according to its developmental mechanism [1]. Not only the changes in the nervous systems, but also neuroinflammation, are associated with the development of neuropathic pain [2].

Among those etiological mechanisms of neuropathic pain, the neuroinflammatory process, via cell-derived inflammatory cytokines and glial activation, is suggested as a debilitating factor in both the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain, which result in sensitization [3–7]. It is well known that the inflammatory mechanism of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) act a cardinal role in the production of neuropathic pain [8,9]. Therefore, inhibiting the inflammatory cascades by modulating pro-inflammatory cytokines has been suggested to reduce or attenuates neuropathic pain following spinal nerve injury [10–12].

Gabexate mesilate, one of the serine protease inhibitors, is a drug with anti-inflammatory properties, which is used for the treatment of pancreatitis [13]. Its property of TNF-α inhibition via monocyte also provides effectiveness in the treatment of sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation [13]. Recent studies have shown that the inhibitory effects of serine protease inhibitor on the pro-inflammatory cytokines can attenuate the development of neuropathic pain [2,14]. Gabexate mesilate also showed a protective effect after spinal cord trauma by inhibition of the increase in the myeloperoxidase activity in an animal model [15]. Moreover, gabexate mesilate has an inhibitory property on the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) which plays a crucial role in inflammatory pain in the central nervous system [16], and can decrease monocytic TNF-α production [15]. It also has the effect of decreasing the release of nitric oxide (NO) by inhibiting the NO pathway in rat C6 glioma cells [17]. NO is expressed in response to proinflammatory cytokines after spinal cord injury [18] and plays potential roles in neuropathic pain [19].

Thus, we hypothesized that gabexate mesilate can attenuate mechanical allodynia caused by spinal nerve ligation (SNL) by inhibiting NF-κB activation, as well as reducing the expressions of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). This study examined the effects of gabexate mesilate on the development of mechanical allodynia and the levels of expressions of NF-κB, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS in rats following neuropathic pain evoked by SNL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Animal preparation

This study was conducted after approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chosun University (CIACUC 2017-S0041). This study also followed the International Association for the Study of Pain guidelines on ethical standards for the investigation of experimental pain in animals [20]. A total of 64 male Sprague-Dawley (specific pathogen-free) were purchased from Damul Science (Daejeon, Korea) and used for the study. The rats (100–120 g) were housed in separate cages with free access to food and water and a light:dark cycle of 12:12. The cages were maintained with a temperature between 20°C and 23°C.

2. Introduction of neuropathic pain

Segmental SNL was conducted according to the experimental model of neuropathic pain proposed by Chung et al. [21,22]. Forty-four rats were used for the segmental SNL. Under the general anesthesia with sevoflurane, the midline of the L5-S2 spine was incised and the left paraspinal muscles were exposed. The left paraspinal muscles were dissected and separated from the spinous process. After exposure of the spine, the transverse process of the L6 spine was removed with a small rongeur, and the left L5 and L6 spinal nerves were exposed. Each nerve was tightly ligated at the distal site of the dorsal root ganglia with 6–0 silk. Then, the incision wound was sutured. After recovery from anesthesia, the damage to the L4 spinal nerve was examined and the rats with signs of motor nerve damage were excluded from the study. Altogether, 20 rats were used for a sham operation without SNL. The development of neuropathic pain was confirmed by the paw withdrawal threshold (PWT), which was measured using von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) after three days. Rats showing a paw flinching response upon the application of a bending force of less than 4 g were defined as exhibiting mechanical allodynia and were used for the study. Four rats were excluded due to a failure to induce mechanical allodynia, and a total of 60 rats were used for the study.

3. Assessment of mechanical allodynia

The measurement of mechanical allodynia was performed by the PWT using von Frey filaments. The rats were acclimated to the laboratory environment in the cages with a mesh floor for 30 minutes. The von Frey filaments were applicated vertically for 5 seconds to the plantar surface of the hind paw. The mechanical allodynia was determined and recorded by a positive response such as an abrupt withdrawal or flinching of the hind paw. The cut-off value was a negative response to 15 g. The PWT was calculated using the up and down method with an application of a series of eight von Frey filaments (0.4, 0.7, 1.2, 2.0, 3.6, 5.5, 8.5, and 15 g) [23].

The change in mechanical allodynia across time, measured by a series of tests, was conducted on the 3rd, 7th, and 14th days following SNL.

4. Groups and drug administration

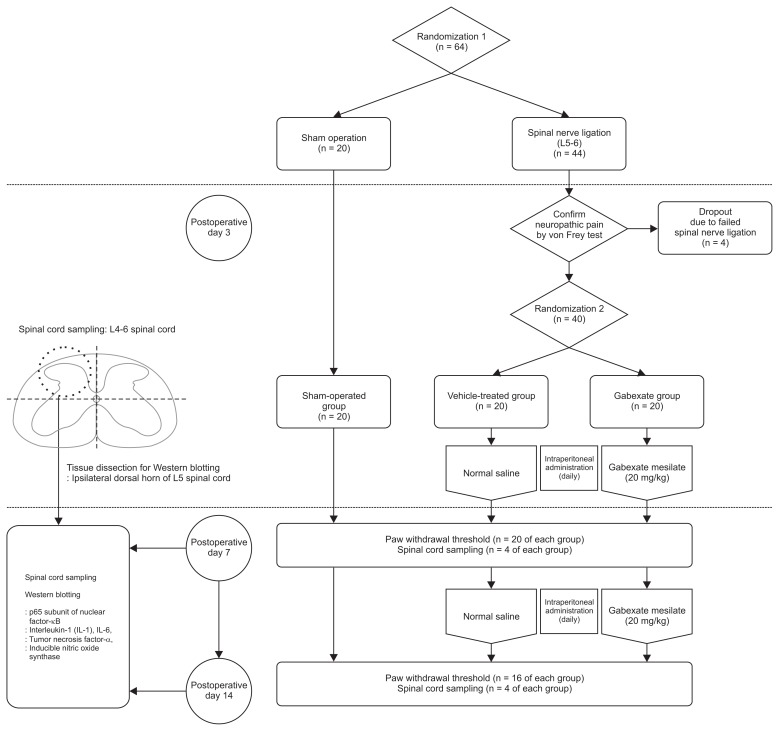

The rats were first randomized into two groups, and then underwent either a sham operation (n = 20) or SNL (n = 44). After confirming the development of neuropathic pain on the 3rd day following SNL, the rats who exhibited mechanical allodynia after SNL (n = 40) were randomized into two groups, a gabexate group and control group (Fig. 1). Randomization was done using the random numbers generated by a computer. Eventually, the rats were randomized into three group (each n = 20) and prepared drugs were administered intraperitoneally daily until the end of the study period, according to the group. Rats in the sham-operation group underwent a sham operation without SNL and were not administered any drugs. The rats in the vehicle-treated group were administered normal saline intraperitoneally daily. The rats in gabexate group were administered 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate (Foy®; Donga ST Pharm., Seoul, Korea) intraperitoneally daily [15].

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study design.

5. Spinal cord sampling

On the 7th and 14th day, spinal cord sampling was performed (total n = 24; n = 4 of each group for each day). After overdose anesthesia with sevoflurane, rats were euthanized by decapitation. Immediately, an 18-gauge needle was inserted into the caudal end of the vertebral column which was flushed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. A 1-cm section of the lumbar spinal cord at L4–L6 was removed from the intact frozen cord and weighed. The tissue of the ipsilateral dorsal spinal cord at L4–L6 was obtained and immediately stored at −70°C using liquid nitrogen until homogenization.

6. Western blotting

Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), a p65 subunit of NF-κB, and iNOS were measured by Western blotting on the 7th and 14th day following SNL. Tissue samples which were obtained from the spinal cord at L4–L6 were dissected (Fig. 1) and the ipsilateral dorsal horn of the L5 spinal cord were homogenized in a lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, #89900, Waltham, MA) with a Dounce homogenizer (Bellco Glass, Vineland, NJ), and further lysed with RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cell lysates were quantified for protein content, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 12%–15% acrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and then immunoblotted with corresponding antibodies. The antibodies used were: IL-6 (R&D Systems, MAB5061, Minneapolis, MN), IL-1β (R&D Systems, MAB501), TNF-α (R&D Systems, MAB510), iNOS (Novous Biologicals, NB-300-605, Centennial, CO), and p65 (Cell Signaling, #8242, Danvers, MA). Chemiluminescence Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Millipore) were used for the visualization of the bands. Quantified densitometry analysis was done with ImageJ densitometry software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

7. Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated using “G*Power3” software (available freely at http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3). The effect size was calculated as 0.77 according to the results of the previous study which used another serine protease inhibitor [2]. Using α = 0.05 with a power 95%, the total sample size was calculated as 30 for the statistical analysis of three consecutive measurements with PWT with repeated measures analysis of variance in three groups. After estimating the drop-out rate to be 20%–40% during the operation, we intended to include 12–14 rats in each group for the PWT, and 8 rats were added for the spinal cord sampling. In total, we included 20–22 rats for the study in each group.

The data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The differences between groups in the PWT test were analyzed by repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance and Scheffe’s posthoc test and analyzed by a t-test according to the day. The densitometry data obtained from Western blotting was analyzed by a two-tailed t-test. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

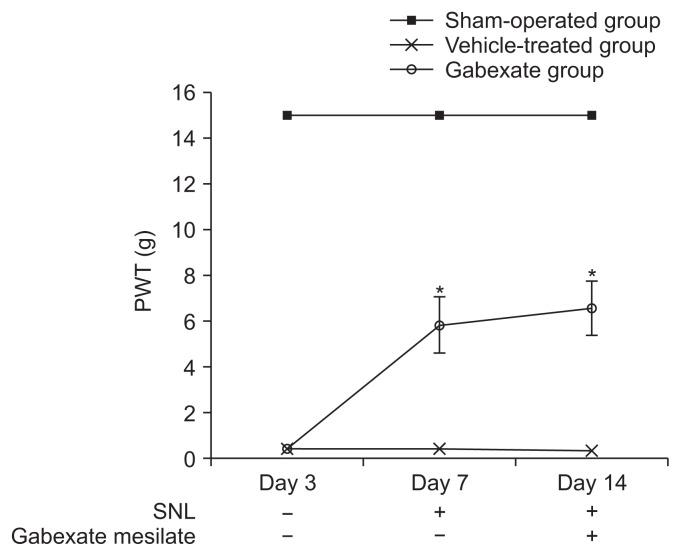

At the 3rd day after the SNL procedure, significant decreases in the PWT were observed (P < 0.001) in the rats of the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group compared with the sham-operation group, and the development of mechanical allodynia was confirmed (Fig. 2). The mechanical allodynia was not observed in the rats in the sham-operation group. The rats of the gabexate group, which were administered 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate intraperitoneal daily after 3rd day following SNL, showed a higher PWT than those of the vehicle-treated group during the observation period (P < 0.001). These results indicate that gabexate mesilate attenuate the development of mechanical allodynia induced by SNL.

Fig. 2.

Paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) across time. The PWT was observed from the 3rd day until the 14th day following spinal nerve ligation (SNL). On the 3rd day after SNL, mechanical allodynia was confirmed. The rats of the gabexate group showed higher PWT than those of the vehicle-treated group during the observation period (P < 0.001). The sham-operation group, sham operation only without SNL or drug; the vehicle-treated group, the control group treated with intraperitoneal normal saline daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period; the gabexate group, the experimental group treated with intraperitoneal 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period. *P < 0.05 compared with the vehicle-treated group.

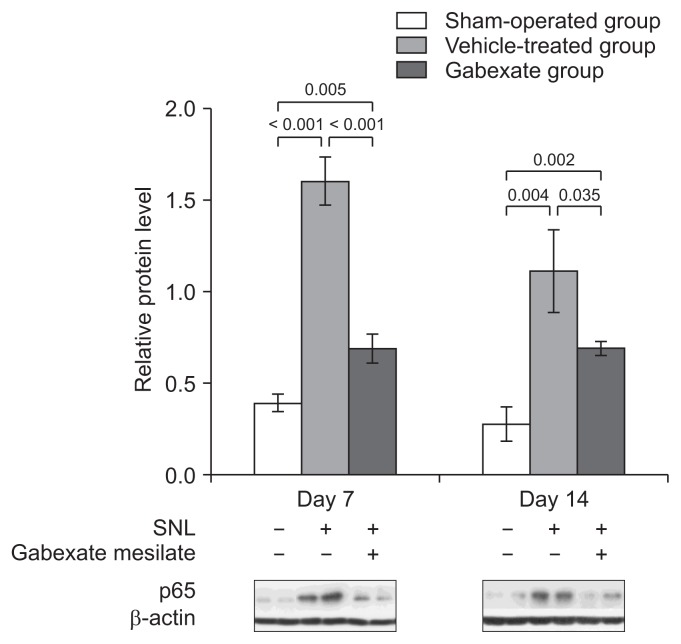

The inhibitory effect of gabexate mesilate on the activation of NF-κB was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3). The expression of the p65 subunit of NF-κB were significantly increased in the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group, which underwent SNL, compared with the sham-operation group (P < 0.001) at both the 7th and 14th day after SNL. The expression of p65 was markedly decreased in the gabexate group, which was administered gabexate mesilate intraperitoneally, compared with the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The expression of p65 subunit of nuclear factor-κB at the ipsilateral dorsal horn of L5 spinal cord across time. The levels of p65 were significantly increased in the vehicle-treated group and gabexate group compared with the sham-operation group (P < 0.001). The expression of p65 was markedly decreased in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05) throughout the experimental period. The sham-operation group, sham operation only without spinal nerve ligation (SNL) or drug; the vehicle-treated group, the control group treated with intraperitoneal normal saline daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period; the gabexate group, the experimental group treated with intraperitoneal 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period.

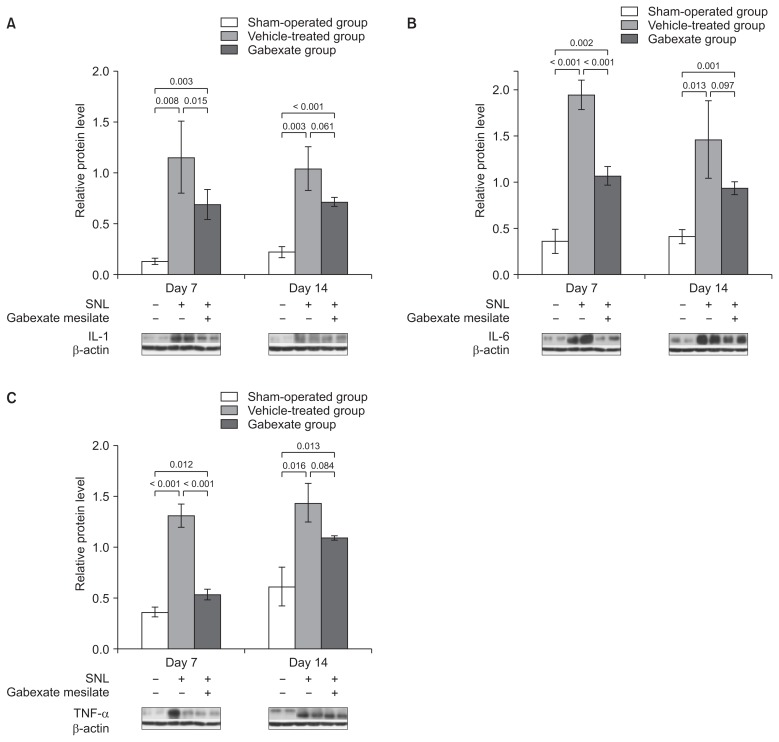

The effects of gabexate mesilate on the expressions of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 (Fig. 4A), IL-6 (Fig. 4B), and TNF-α (Fig. 4C) were also confirmed by western blot analysis. The expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased at both the 7th and 14th day after SNL in the vehicle-treated group and gabexate group, compared with the sham-operation group (P < 0.05). However, the expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were attenuated at 7th day after SNL significantly in the Gabexate group compared with Vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05). Moreover, there were no significant differences at the 14th day in the expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α between the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group (P > 0.05), even though the levels of protein expression were lower in the gabexate group. These results indicate that gabexate mesilate has an inhibitory effect on the expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines after SNL for a short-term period.

Fig. 4.

The levels of interleukin (IL)-1 (A), IL-6 (B), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; C) at the ipsilateral dorsal horn of L5 spinal cord across time. The levels IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were measured at the 7th and the 14th day following spinal nerve ligation (SNL). The expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased in the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group compared with the sham-operation group at both 7th and 14th day after SNL (P < 0.05). After administration of gabexate mesilate, the expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly attenuated in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group at 7th day after SNL (P < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significances in the expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α between the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group at 14th day (P > 0.05). The sham-operation group, sham group; the vehicle-treated group, the control group treated with intraperitoneal normal saline daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period; Group E, the experimental group treated with intraperitoneal 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period.

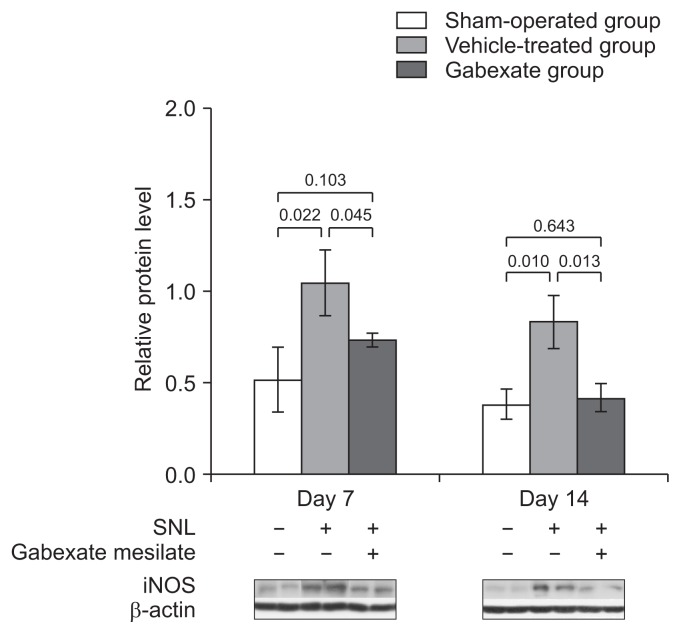

The effect of the gabexate mesilate on the expression of iNOS is shown in Fig. 5. The expression of iNOS was significantly increased at both the 7th and 14th day after SNL in the vehicle-treated group and the gabexate group compared with vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05). The levels of iNOS were significantly decreased at the 7th and 14th day after SNL in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

The expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) at the ipsilateral dorsal horn of L5 spinal cord across time. The levels of iNOS were significantly increased in the vehicle-treated group and the experimental group (group E) compared with the sham-operation group (P < 0.05). The expression of iNOS was markedly decreased in group E compared with the vehicle-treated group throughout the experimental period (P < 0.01). The sham-operation group, sham group; the vehicle-treated group, the control group treated with intraperitoneal normal saline daily after 3rd day following spinal nerve ligation (SNL) until the end of the study period; Group E treated with intraperitoneal 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate daily after 3rd day following SNL until the end of the study period.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the PWT increased in the rats who had been administered 20 mg/kg of gabexate mesilate intraperitoneally daily after the 3rd day following SNL in comparison to the controls. And, the expression of p65, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS has been attenuated at the 7th day after SNL in the gabexate group compared with the vehicle-treated group. These results indicate that gabexate mesilate ameliorated the development of SNL-mediated mechanical allodynia induced by the attenuation of proinflammatory cytokines and NO production for a short-term period via an inhibitory effect on the activation of NF-κB.

In terms of neuroinflammation, serine protease inhibitor has inhibitory properties on the proinflammatory cytokines and has the effect of attenuating the development of neuropathic pain [2,14]. Gabexate mesilate is one of those serine protease inhibitors with properties of anti-inflammation and TNF-α inhibition by the suppression of NF-κB and the NO pathway [13,15,17] which are closely related with an inflammatory response and the development of neuropathic pain after spinal nerve injury. Thus, it was hypothesized that gabexate mesilate, likewise a previous serine protease inhibitor, can attenuate the development of neuropathic pain caused by SNL by inhibition of the neuroinflammatory process in a spinal cord injury.

After the nerve injury, the activation of the neuroinflammatory process at the peripheral nerve and spinal cord starts within 1–3 days [5]. Immune-like glial cells and astrocytes in the dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord are activated and this facilitates the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α [5,24–26]. Previous research provided the evidence that proinflammatory cytokines play a crucial role in the process of neuropathic pain development. The release of TNF-α and overproduction of IL-1β following peripheral nerve injury are related to a rapid immune response [5,27,28], the development of neuropathic pain, and allodynia [29,30]. IL-6 was implicated with the maintenance of neuropathic pain [31]. Moreover, studies show that regional or intrathecal injection of IL-1β and IL-6 induced hypersensitivity to stimuli in rodents [32,33].

Particularly, TNF-α is a major proinflammatory cytokine that not only initiates chronic neuropathic pain by inducing a cascade of additional cytokine production, but is also associated with maintenance of chronic neuropathic pain [5,28]. Targeted intervention using a TNF-α neutralizing antibody in rats with neuropathic pain showed the effect of ameliorating mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia [34]. Secreting a cascade of proinflammatory cytokines promotes a release of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, and serotonin, which are involved with hypersensitivity to pain by affecting afferent nociceptive neurons [35]. These neuronal activations lead to sensitization which enhances the responsiveness of nociceptors to mechanical stimuli. In the current study, the expressions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord were significantly increased as well as the decrease of the PWT appeared to be prominent at the 7th day after SNL. In addition, the mechanical allodynia was reduced after treatment with gabexate mesilate, as the expression of proinflammatory cytokines decreased.

Neuroinflammation is regulated by multiple molecular mechanisms and regulatory factors, and NF-κB is the primary regulator of inflammatory responses [16]. After nerve injury, the NF-κB signaling pathway in the glial cells at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord plays a crucial role in the development of neuropathic pain. The NF-κB signaling pathway regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, chemokines, and pro-algesic molecules [36]. The activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway begins with the phosphorylation of inhibitory NF-κB inhibitors (IκB), and degradation of IκBα leads to translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus [37]. These sequences promote transcription of pro-algesic target genes such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, and lead to upregulation of those downstream target genes [38]. These processes also promote NO expression, one of the potential mediators in the development of neuropathic pain [19]. Selective inhibition of NF-κB activity in glial cells showed anti-hyperalgesic and antiallodynic effects after spinal cord injury by inhibiting IL-6 and iNOS expression [39]. Inhibition of astroglial NF-κB facilitates functional recovery by reducing inflammation following injury of the spinal cord [40]. These reports suggest that NF-κB plays a primary role in the development of mechanical allodynia after SNL.

During the process of neuroinflammation, NO is released into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [35,41]. As inflammatory and proinflammatory mediators are upregulated during chronic inflammation, the primary active form of NO (iNOS) is induced [19,42]. NO reacts with superoxide and produces peroxynitrite, which leads to central sensitization consequently by enhancing phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors [43]. These responses have been suggested as one of the mechanisms of inflammatory neuropathic pain [43]. Previous studies showed the relationship of NO with the inflammatory pain response. Intrathecal administration of NO produces nociceptive behavioral responses [44] whereas NO synthase inhibitors showed an analgesic effect in pain models [35,45].

The results of the current study, which showed increases of p65, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and NO after SNL, were consistent with previous findings. Administration of gabexate mesilate following SNL decreased the expression of the p65 subunit of NF-κB compared with the control group, which was administered normal saline. The inhibitory effect of gabexate mesilate on the expression of NF-κB and iNOS persisted throughout the experimental period. These results agreed with previous reports about gabexate mesilate, which demonstrated the inhibitory effects of NF-κB and the NO pathway [13,15,17]. However, the consequent inhibition of expressions of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) lasted only for a week. The reason for the inconsistency is unclear but is thought to be due to the involvement of several mechanisms in the development of neuropathic pain [42].

Even though TNF-α and IL-1β are the primary cytokines responsible for iNOS induction, which acts through NF-κB, multiple mechanisms such as neuroinflammation, neuroimmune response, ion channels, and other responses are related with the neuropathic pain [42]. According to a previous study about temporal expression of cytokines in the neuropathic pain model, inflammatory cytokines mainly affect neuroinflammation in the early phase. After SNL, maximal increases of IL-1 and TNF-α were shown at the 3rd day after spinal nerve injury and decreased to control levels by the 14th day [46]. Thus, inflammatory cytokines might have the principal role in the initiation of neuroinflammation [2]. Moreover, maintenance of mechanical allodynia from neuropathic pain is also associated with histological changes caused by T cell infiltration or complement and macrophage activation in the peripheral nerve and spinal cord, besides inflammatory mechanisms [5,7,9,47]. These multiple mechanisms of neuropathic pain also seem to be responsible in the stagnation of the increase of the PWT despite continuous use of gabexate mesilate at the 14th day. Though our results demonstrated suppression of NF-κB activity by gabexate mesilate in the dorsal spinal cord sufficient to attenuate the mechanical allodynia, and the neuropathic pain induced by SNL, the antiallodynic effects of gabexate mesilate were mediated by consequent inhibition of the expressions of proinflammatory cytokines and iNOS.

The limitations of the current study are as follows: First, we only assessed the effects of gabexate mesilate on neuropathic pain for a short-term period. Long-term investigation should be done. Second, only one dose of gabexate mesilate (20 mg/kg intraperitoneally daily) was used according to a human study [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate various concentrations of gabexate mesilate, and dose-finding evaluation is needed. Third, we focused only on the involvement of NF-κB, proinflammatory cytokines, and the NO pathway in the influence of gabexate mesilate. Further molecular research about the effects of gabexate mesilate on the mechanisms of neuropathic pain are needed. Fourth, further histological analysis of microglia activation such as immunohistochemistry are needed to confirm the hypothesis of the current study that gabexate may attenuate the development of mechanical allodynia via involvement in the regulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines. And, quantitative analysis of nuclear p65 with nuclear fractionation is needed to confirm transcriptional activation of NF-κB precisely. Finally, gabexate mesilate is not yet an analgesic drug for neuropathic pain treatment. Further evaluations of its clinical applications are needed.

In conclusion, gabexate mesilate increased PWT and attenuated the development of mechanical allodynia after SNL. The effect of gabexate mesilate on neuropathic pain seems to be involved with consequence anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting expressions of proinflammatory cytokines and iNOS via inhibition of the expression of NF-κB in the dorsal spinal cord. Further evaluation of gabexate mesilate at molecular levels on the development of neuropathic pain is needed.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Seon Hee Oh: Investigation; Hyun Young Lee: Writing/manuscript preparation; Young Joon Ki: Investigation; Sang Hun Kim: Writing/manuscript preparation; Kyung Joon Lim: Writing/manuscript preparation; Ki Tae Jung: Writing/manuscript preparation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This study was supported by research funds from Chosun University, 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gao J, Tang C, Tai LW, Ouyang Y, Li N, Hu Z, et al. Pro-resolving mediator maresin 1 ameliorates pain hypersensitivity in a rat spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1511–9. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S160779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh SH, So HJ, Lee HY, Lim KJ, Yoon MH, Jung KT. Urinary trypsin inhibitor attenuates the development of neuropathic pain following spinal nerve ligation. Neurosci Lett. 2015;590:150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: a therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:319–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacerdote P, Franchi S, Moretti S, Castelli M, Procacci P, Magnaghi V, et al. Cytokine modulation is necessary for efficacious treatment of experimental neuropathic pain. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:202–11. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin PJ, Moalem-Taylor G. The neuro-immune balance in neuropathic pain: involvement of inflammatory immune cells, immune-like glial cells and cytokines. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;229:26–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha MK, Jeon S, Suk K. Glia as a link between neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain. Immune Netw. 2012;12:41–7. doi: 10.4110/in.2012.12.2.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moalem G, Tracey DJ. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:240–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zelenka M, Schäfers M, Sommer C. Intraneural injection of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha into rat sciatic nerve at physiological doses induces signs of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;116:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers RR, Campana WM, Shubayev VI. The role of neuroinflammation in neuropathic pain: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:8–20. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schäfers M, Brinkhoff J, Neukirchen S, Marziniak M, Sommer C. Combined epineurial therapy with neutralizing antibodies to tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 receptor has an additive effect in reducing neuropathic pain in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2001;310:113–6. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommer C, Petrausch S, Lindenlaub T, Toyka KV. Neutralizing antibodies to interleukin 1-receptor reduce pain associated behavior in mice with experimental neuropathy. Neurosci Lett. 1999;270:25–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JH, Kwak SH, Jeong CW, Bae HB, Kim SJ. Effect of ulinastatin on cytokine reaction during gastrectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;58:334–7. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.58.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moggia E, Koti R, Belgaumkar AP, Fazio F, Pereira SP, Davidson BR, et al. Pharmacological interventions for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011384. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011384.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung KT, Lee HY, Yoon MH, Lim KJ. The effect of urinary trypsin inhibitor against neuropathic pain in rat models. Korean J Pain. 2013;26:356–60. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.4.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taoka Y, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Murakami K, Kushimoto S, Johno M, et al. Gabexate mesilate, a synthetic protease inhibitor, prevents compression-induced spinal cord injury by inhibiting activation of leukocytes in rats. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:874–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199705000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shih RH, Wang CY, Yang CM. NF-kappaB signaling pathways in neurological inflammation: a mini review. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:77. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colasanti M, Persichini T, Venturini G, Menegatti E, Lauro GM, Ascenzi P. Effect of gabexate mesylate (FOY), a drug for serine proteinase-mediated diseases, on the nitric oxide pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:453–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrasco C, Naziroğlu M, Rodríguez AB, Pariente JA. Neuropathic pain: delving into the oxidative origin and the possible implication of transient receptor potential channels. Front Physiol. 2018;9:95. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freire MA, Guimarães JS, Leal WG, Pereira A. Pain modulation by nitric oxide in the spinal cord. Front Neurosci. 2009;3:175–81. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.024.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–10. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–63. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung JM, Kim HK, Chung K. Segmental spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. Methods Mol Med. 2004;99:35–45. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-770-X:035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thacker MA, Clark AK, Marchand F, McMahon SB. Pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathic pain: immune cells and molecules. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:838–47. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000275190.42912.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uçeyler N, Sommer C. Cytokine regulation in animal models of neuropathic pain and in human diseases. Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao YJ, Zhang L, Samad OA, Suter MR, Yasuhiko K, Xu ZZ, et al. JNK-induced MCP-1 production in spinal cord astrocytes contributes to central sensitization and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4096–108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3623-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamash S, Reichert F, Rotshenker S. The cytokine network of Wallerian degeneration: tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1alpha, and interleukin-1beta. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3052–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung L, Cahill CM. TNF-alpha and neuropathic pain--a review. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gui WS, Wei X, Mai CL, Murugan M, Wu LJ, Xin WJ, et al. Interleukin-1β overproduction is a common cause for neuropathic pain, memory deficit, and depression following peripheral nerve injury in rodents. Mol Pain. 2016;12 doi: 10.1177/1744806916646784. 1744806916646784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Wang J, Wang Z, Dong C, Dong X, Jing Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α of red nucleus involved in the development of neuropathic allodynia. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:233–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding CP, Xue YS, Yu J, Guo YJ, Zeng XY, Wang JY. The red nucleus interleukin-6 participates in the maintenance of neuropathic pain induced by spared nerve injury. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:3042–51. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Cao DL, Jiang BC, Yang T, Gao YJ. MicroRNA-146a-5p attenuates neuropathic pain via suppressing TRAF6 signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;49:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Jiang BC, Cao DL, Zhang ZJ, Zhang X, Ji RR, et al. TRAF6 upregulation in spinal astrocytes maintains neuropathic pain by integrating TNF-α and IL-1β signaling. Pain. 2014;155:2618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin TB, Hsieh MC, Lai CY, Cheng JK, Chau YP, Ruan T, et al. Fbxo3-dependent Fbxl2 ubiquitination mediates neuropathic allodynia through the TRAF2/TNIK/GluR1 cascade. J Neurosci. 2015;35:16545–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2301-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy D, Zochodne DW. NO pain: potential roles of nitric oxide in neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. 2004;4:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2004.04002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu DL, Zhao LX, Zhang S, Du JR. Peroxiredoxin 1-mediated activation of TLR4/NF-κB pathway contributes to neuroinflammatory injury in intracerebral hemorrhage. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;41:82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pei W, Zou Y, Wang W, Wei L, Zhao Y, Li L. Tizanidine exerts anti-nociceptive effects in spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain through inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:3209–19. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee KM, Kang BS, Lee HL, Son SJ, Hwang SH, Kim DS, et al. Spinal NF-kB activation induces COX-2 upregulation and contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3375–81. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meunier A, Latrémolière A, Dominguez E, Mauborgne A, Philippe S, Hamon M, et al. Lentiviral-mediated targeted NF-kappaB blockade in dorsal spinal cord glia attenuates sciatic nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. Mol Ther. 2007;15:687–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brambilla R, Bracchi-Ricard V, Hu WH, Frydel B, Bramwell A, Karmally S, et al. Inhibition of astroglial nuclear factor kappaB reduces inflammation and improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2005;202:145–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivot JP, Montagne-Clavel J, Besson JM. Subcutaneous formalin and intraplantar carrageenan increase nitric oxide release as measured by in vivo voltammetry in the spinal cord. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:25–34. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schomberg D, Ahmed M, Miranpuri G, Olson J, Resnick DK. Neuropathic pain: role of inflammation, immune response, and ion channel activity in central injury mechanisms. Ann Neurosci. 2012;19:125–32. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.190309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao X, Kim HK, Chung JM, Chung K. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in enhancement of NMDA-receptor phosphorylation in animal models of pain. Pain. 2007;131:262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoue T, Mashimo T, Shibata M, Shibuta S, Yoshiya I. Rapid development of nitric oxide-induced hyperalgesia depends on an alternate to the cGMP-mediated pathway in the rat neuropathic pain model. Brain Res. 1998;792:263–70. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roche AK, Cook M, Wilcox GL, Kajander KC. A nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor (L-NAME) reduces licking behavior and Fos-labeling in the spinal cord of rats during formalin-induced inflammation. Pain. 1996;66:331–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee HL, Lee KM, Son SJ, Hwang SH, Cho HJ. Temporal expression of cytokines and their receptors mRNAs in a neuropathic pain model. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2807–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Röyttä M, Wei H, Pertovaara A. Spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathy in the rat: sensory disorders and correlation between histology of the peripheral nerves. Pain. 1999;80:161–70. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]