Abstract

As the prevalence and impact of lung diseases continue to increase worldwide, new therapeutic strategies are desperately needed. Advances in lung-regenerative medicine, a broad field encompassing stem cells, cell-based therapies, and a range of bioengineering approaches, offer new insights into and new techniques for studying lung physiology and pathophysiology. This provides a platform for the development of novel therapeutic approaches. Applicability to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease of recent advances and applications in cell-based therapies, predominantly those with mesenchymal stromal cell–based approaches, and bioengineering approaches for lung diseases are reviewed.

Keywords: bioengineering, cell therapy, mesenchymal stromal cell

One of the earliest references to the concept of regenerative medicine is found in a 1992 article on hospital administration, in a series of short paragraphs on future technologies that would impact hospitals and medical care: “A new branch of medicine will develop that attempts to change the course of chronic disease and in many instances will regenerate tired and failing organ systems” (1). As this initial concept has evolved, regenerative medicine can be thought of as encompassing several related disciplines. One of these is stimulating the body’s own repair mechanisms to heal previously irreparable tissues or organs. This is particularly applicable to complex tissues such as lung, in which limited endogenous reparative mechanisms can be overcome by either the severity of illness or the chronicity of the insult; that is, cigarette smoking. Arguably, a means to stimulate controlled alveolar and airway regeneration in situ in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other destructive lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis would be a significant advance. Use of pharmacologic means to stimulate reparative postnatal lung growth, for example, administration of retinoic acid, although promising in mice, did not have beneficial effects in clinical trials (2). More recently, and as further discussed below, cell-based therapies, utilizing systemic or intratracheal administration of a variety of cell types including endogenous lung progenitor cells, induced pluripotent cell–derived lung epithelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells, and allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), have been postulated to promote structural and functional regeneration of gas exchange (3, 4). A broader field of antiinflammatory actions of MSCs, and a primary focus of this review, has also been explored with the primary goal of decreasing inflammation and injury without necessarily promoting structural repair in both preclinical lung disease models and in clinical trials in lung diseases (5, 6). A second broad regenerative medicine approach is that of growing tissues and organs in the laboratory for implantation when the body cannot heal itself. Although there has been success with tissues such as skin, muscle, and bone, this has been a challenge for lung (5). Several developing strategies such as “organ on a chip,” organoid culturing, three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting, and de- and recellularization have provided novel approaches, particularly with respect to lung (7–11). A third broad area of regenerative medicine is the development of adjunct devices to replace or augment defective tissue or organ function. Left ventricular assist, portable dialysis devices, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices are good examples of advanced biomedical engineering approaches that can augment defective organ functions for both short and sometimes more prolonged time periods (12). As will be discussed, there is significant unmet need and thus opportunity for new types of lung assist devices, particularly in ambulatory patients with end-stage lung disease on transplant waiting lists or who will never qualify for lung transplant.

COPD as a paradigmatic lung disease is both a challenge and opportunity for regenerative medicine. Better understanding of the role of endogenous progenitor cells, particularly basal airway epithelial cells, and their potential dysfunction in the etiology of COPD and also of lung cancer, are covered in the other State of the Art reviews from this conference. Investigations utilizing MSCs for COPD have encompassed both preclinical studies as well as clinical investigations that reflect the potential, but also the realistic practicalities, of attempting MSC-based therapies in a chronic destructive lung disease. Organoid and lung-on-a-chip strategies have revealed new insights into lung cell biology. Lung de- and recellularization strategies, although not directly targeting COPD, have revealed fundamental knowledge about the role of the COPD lung extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell–matrix interactions in COPD pathophysiology. These and related areas are reviewed below.

Cell-based Therapies for COPD

The idea of administering a stem cell, either systemically or directly into the lung, to repair damaged or dysfunctional lung had significant genesis from work published 2001 by Diane Krause and colleagues at Yale University (13). This paradigm-shifting publication suggested that systemically hematopoietic stem cells could engraft in various tissues, including lung, and acquire tissue-specific phenotype and possibly even function. This initiated a broad-based effort attempting to demonstrate that various types of adult stem and progenitor cells including hematopoietic stem cells, MSCs, endothelial progenitor cells, as well as embryonic stem cells could engraft in diseased lung and participate in both structural and functional repair (reviewed in Reference 14). These early studies were subsequently found to predominantly represent artifacts and suboptimal use of photomicroscopy techniques, and the concept of stem cell engraftment in lung was not believed to be a biologic phenomenon of any significance (15, 16). However, data suggest that endogenous lung airway progenitor cells, for example, cytokeratin 5/14+ basal airway epithelial cells, or induced pluripotent stem cell–derived lung progenitor cells, may have more potent engraftment properties and potentially contribute to functional as well as structural repair (3, 4). Although not the focus of this review, this is an exciting and rapidly progressing area that may provide significant reconsideration of potential structural repair of the lung by being further able to manipulate these cells in situ or by their exogenous administration.

Emphasis in the study of MSCs for use in COPD and other lung diseases accordingly has shifted to both understanding and exploiting their paracrine and other properties, independent of their differentiation abilities (17). This is particularly important for COPD as it is a chronic inflammatory as well as destructive disease with ongoing pulmonary and systemic inflammation even after smoking cessation. Although the full spectrum of MSC paracrine activities is still being determined, a partial list of actions includes the ability to sense local inflammatory environments through expression and activation of damage- and pathogen-associated molecular pattern receptors such as the Toll-like receptors (18). The MSCs will then release a spectrum of antiinflammatory and other ostensibly reparative mediators including antiinflammatory cytokines, antibacterial peptides, proangiogenic factors, and extracellular vesicle particles that can affect both lung epithelial cells as well as resident inflammatory and immune cells including alveolar macrophages (17, 18). Mitochondrial transfer from MSCs to damaged lung epithelial cells has also been observed (19).

These mechanisms have been observed in in vitro studies in which exposure to MSCs or their secreted products affects lymphocyte proliferation and function as well as macrophage phenotype and activation (16, 17). Accordingly, there have been a growing number of publications in which systemic or intratracheal MSC administration results in amelioration of injury in a range of preclinical lung disease models in rodents, larger animals (sheep and pigs), and explanted human lungs (reviewed in References 3 and 20). These include a number of studies in rodent COPD models including those induced by exposure to elastase, papain, or cigarette smoke (21–44). Although these models have known limitations in accurately reflecting clinical COPD structural and physiologic pathology, particularly those utilizing papain and elastase, improvements in experimental outcomes were observed in many of these studies. For example, in mice exposed to cigarette smoke for a 24-week period, systemic administration of either mouse bone marrow– or human adipose–derived MSCs every other week for the last 2 months resulted in decreased pulmonary (lung inflammation and histologic injury) as well as systemic effects (decreased weight loss and increased subcutaneous fat) (29). Various paracrine pathways, including mitochondrial transfer, have been suggested as potential mechanisms by which the MSCs are having protective effects (36, 38, 39, 42, 44). These results suggest a potential role for MSC administration in clinical therapeutics for COPD. It is to be emphasized that, although there may be effects of MSCs on existing endogenous progenitor cells in the lung, current paradigms of MSC actions in both preclinical models of COPD and clinical trials focus on antiinflammatory paracrine actions rather than structural repair (3, 4, 14, 38). Conversely, several studies have also demonstrated the damaging effects of cigarette smoke on MSC functions, and this will need to be considered in clinical trials of MSCs (45–47).

However, it is critical to understand the biology of MSCs in the context of a chronic inflammatory and destructive lung disease such as COPD. MSCs reside in many tissues, most notably in bone marrow and adipose, but have also been identified in the lung. However, unlike bone marrow neutrophil populations, MSCs are not recruited out of the marrow or adipose in response to inflammatory signals. Rather, they are extracted from either bone marrow or adipose tissue (autologous) or from those tissues in an external source, for example, healthy normal volunteers, expanded in culture, and used either directly or after freezing and thawing. After systemic administration, MSCs lodge in the lung as the first major capillary bed encountered, predominantly through cell surface integrin actions still being defined (16, 17). Once in the lung the cells do not engraft but rather release a range of soluble mediators and may also have some direct cell–cell interactions with resident pulmonary epithelial or vascular endothelial cells. Available data demonstrate that the MSCs are then cleared from the lungs over a 1- to 3-day period. Similar observations have been made after direct airway (intratracheal) MSC administration. Clearance mechanisms are still being defined but include phagocytosis/efferocytosis by alveolar macrophages, induction of apoptosis, and other mechanisms (17). Whether effects rendered on resident inflammatory cells or immune cells recruited to the lungs, effects presumably conducive to repair of inflammation and injury, persist is still being elucidated.

Accordingly, despite encouraging results in rodent models, the mechanisms by which systemically or intratracheally administered MSCs can have meaningful clinical effects in a chronic disease such as COPD are not clear. There have been several clinical trials of MSC-based therapies in COPD to date (reviewed in References 4 and 48). These have been predominantly phase 1 safety trials and (in those trials that have published results) uniformly demonstrate no obvious safety issues including no evidence of infusional toxicities (cell emboli) and no significant adverse effects for follow-up periods as long as 2 years (49–52). However, none of these have suggested efficacy in either pulmonary function or quality of life indicators. A decrease in circulating C-reactive protein was observed in subjects who received MSCs versus vehicle control in patients with elevated baseline C-reactive protein at study entry (49). Comparably, decreases in several circulating inflammatory mediators and changes in circulating T-cell populations were observed in patients with stable COPD after systemic MSC administration (52). These provide important hypothesis-generating data even in the absence of clinical efficacy.

Possible explanations for the lack of beneficial effects on clinical outcomes are multiple and include MSC source (bone marrow vs. other), administration route, dosage, and frequency and timing of administration(s) as well as host factors. Less well understood is the fate of the MSCs or their secreted products, including extracellular vesicle particles, after systemic or intratracheal administration to patients with COPD (52). These will likely be critical factors in determining whether a relatively short-lived cell infusion (days) will ever have a chance for therapeutic efficacy.

One unfortunate and troubling outcome of the growing interest in cell-based therapies for COPD has been the expansion of unproven cell therapies and stem cell medical tourism both in the United States and globally (53). These unproven and often unsafe approaches are aggressively marketed and highly visible to desperate patients through the Internet and other forms of social media. Organizations such as the International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy (ISCT) and the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) have taken strong public stances against this stem cell medical tourism, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is beginning to take stronger actions (53, 54). The American Thoracic Society (ATS) Assembly on Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology Stem Cell Working Group has been active in this area and has advocated with other respiratory groups worldwide for intensification of communication and collaboration between patients and respiratory health professionals, including patient and caregiver information on the ATS website (55, 56).

One particular area of concern is the listing of clinical trials on the NIH ClinicalTrials.gov website. As of May 7, 2018, 73 trials of MSC-based therapies for lung disease, including COPD, were listed on the www.clinicaltrials.gov website. Some of these are well-designed, peer-reviewed, FDA-sanctioned trials compliant with contemporary ethical, scientific, and regulatory standards. However, a significant number of listings are studies of dubious scientific rationale that do not comply with ethical and legal norms governing human subject research. Further, many of these charge participants $7,500 to $20,000 USD. This creates a situation in which patients can be misled into participating in unproven therapies at significant cost to themselves. The ATS Stem Cell Working Group, along with a number of other national and international organizations, is working with the FDA to rectify this situation (54, 57).

Lung Bioengineering

In parallel with approaches for clinical administration of MSCs and studies of other cell types as potential therapeutic strategies for COPD, there is widespread interest in approaches for growing functional lung tissue ex vivo for potential use in transplantation and for the study of lung biology and pathophysiology. As such, engineering a functional gas exchange system, whether suitable for implantation and use in lung transplantation or for use as an external lung assist device, is an exciting yet challenging area of active growth. Various approaches are briefly considered below, with particular reference to application in COPD.

Lung Organoids

An explosion of interest in organoid technologies has paralleled advances in understanding of endogenous lung progenitor cell biology and the increasing sophistication in deriving lung progenitor as well as airway and alveolar epithelial cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent cells. Organoid technology is a powerful tool for studying lung developmental biology, cell–cell interactions, and cell–matrix interactions, and further serves as a pharmaceutical platform for screening and evaluating small molecules and other potential new therapeutic agents (8, 58–61). Organoid technology has not yet been extensively utilized to study defective epithelial cell biology in COPD but will be a powerful tool with which to do so.

Three-Dimensional Bioprinting and Lung-on-a-Chip

Increasing technical progress been made in the sophistication of 3D bioprinters along with advances in biomaterial science including ECM-based bioinks (62). This includes increasing ability to include live cells in the printing processes and creation of complex multilayered printed tissues. A growing number of studies are using these approaches for clinical management of diseases of the larger airways (trachea/mainstem bronchi), usually in the setting of congenital defects, cancer, or trauma (63, 64). Although promising, the field has been undermined by scandal involving cardiothoracic surgeon Paolo Macchiarini and as such highlights the need for solid supporting preclinical data and appropriate rigor in clinical applications (65). Three-dimensional printing has had less progress in lung parenchymal applications as yet, in large part due to the current limitations on the printing resolution of current 3D bioprinters. Several groups have printed surface areas to use for study of the air–liquid interface and lung epithelial cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (7). Increasing advances in technique such as stereolithography add power to this approach but at present, 3D bioprinting of alveoli remains an elusive goal. Lung-on-a-chip technologies are comparably powerful tools with which to investigate cell–cell, cell–matrix, and cell–environment interactions. Incorporation of cyclic mechanical stretch and different oxygen tensions offers a means to comprehensively assess multiple variables in a tightly controlled manner (8, 66, 67). Lung-on-a-chip technologies also provide a strong platform for pharmaceutical testing. However, neither 3D bioprinting nor lung-on-a-chip has yet been extensively utilized to study lung epithelial or progenitor cells and/or matrix obtained from patients with COPD. These are anticipated to be highly fruitful areas of future studies.

Ex Vivo Lung Generation: De- and Recellularization

A promising and growing area of investigation is that of ex vivo bioengineering of functional lung tissue that could then be implanted into patients with end-stage COPD or other lung diseases. Either biologic scaffolds or fabricated 3D matrices are seeded with stem, progenitor, or other lung cells and cultured in bioreactor chambers to recapitulate gas exchange function. Ideally, the cells utilized would be obtained from the individual transplant recipient. If successful, this would then help to alleviate the ongoing shortage of donor lungs available for transplantation and to minimize subsequent immune rejection. These approaches have been increasingly successfully utilized in regeneration of other tissues including skin, vasculature, cartilage, bone, and trachea and more recently more complex organs including trachea, heart, and liver. The majority of work in this area has focused on biologic scaffolds utilizing lungs treated to remove resident cells and cell debris, leaving behind the intact ECM macro- and microarchitecture scaffolding (decellularization) (68). This includes preservation of native airway and vascular structure and provides a native acellular matrix for cell seeding and structural and functional recellularization. This approach also provides a novel culture system with which to study cell–matrix interactions and the effect of environmental factors such as mechanical stretch on lung cell growth and development (69–72). A range of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach in small (rodent), large (pig), and human lungs (9, 68).

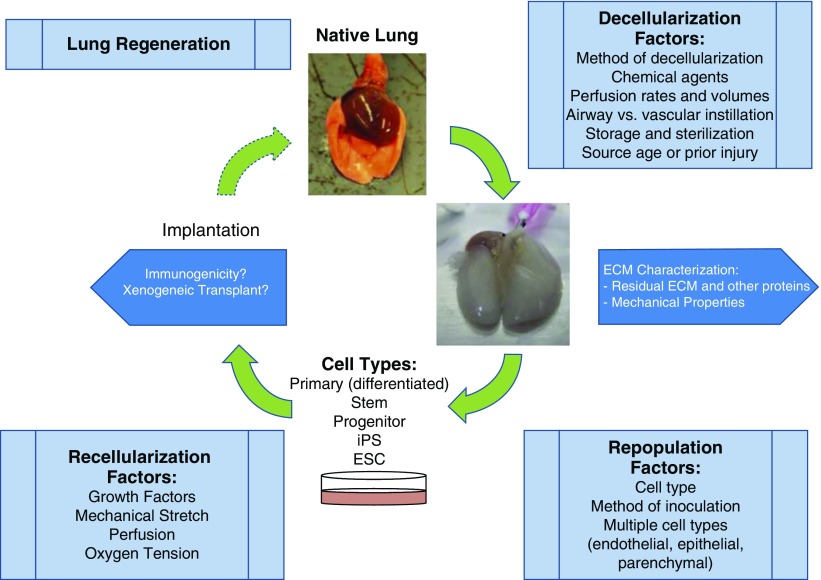

However, despite much progress, functional lung tissue that exhibits robust gas exchange has yet to be produced. This reflects a number of considerations summarized in Figure 1, including the decellularization method utilized and the subsequent quality of the remaining ECM in terms of remaining ECM and matrisome proteins, the recellularization strategies utilized, consideration of relevant environmental factors such as cyclic mechanical stretch, and the bioreactor technologies utilized (9, 68). Further technologic developments are required to overcome these hurdles, and a range of strategies including use of xenogeneic scaffolds of decellularized pig lungs seeded with human lung cells are being investigated (73, 74). Nonetheless, it will likely be a number of years before this approach yields functional gas exchange tissue that can be clinically utilized. Notably, decellularized lungs from both rodents with experimentally induced emphysema and patients with COPD are significantly altered compared with lungs obtained from normal mice or patients (75, 76). This provides a powerful tool with which to assess the role of deranged ECM in the pathogenesis of COPD.

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstrating considerations for utilizing decellularized lung scaffolds. ECM = extracellular matrix; ESC = embryonic stem cell; iPS = induced pluripotent stem (cell). Reprinted by permission from Reference 68.

Cell Sources for ex Vivo Lung Bioengineering

An important consideration for the above-mentioned approaches is the origin of cells to be utilized, particularly for a clinically translatable product. Ideally, cells derived from the eventual transplant recipient would mitigate immune responses and potential rejection. How to best achieve this is unclear as the number of cells, be they, for example, differentiated lung epithelial cells or airway epithelial progenitor cells, that might be obtained from lung biopsy or airway brushings is limited, as is the ability to expand these in culture. Further, the range of cell types to be utilized, for example, in recellularization strategies, is quite large and there is the additional challenge of seeding them into the proper locations in the decellularized scaffolds (68). Use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), including the use of gene-editing techniques applied to correct any genetic or acquired chromosomal defects, offers a significant potential advantage given the progress in deriving functional airway and alveolar epithelial cells as well as other types of lung cells and the ability to expand these cells more effectively in culture (77). Work demonstrates that iPSC-derived inflammatory cells rather than epithelial or other lung structural cells, for example, alveolar macrophages, may also be useful in clinical applications for disease such as pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (78). This raises the possibility of seeding decellularized scaffolds with autologous, gene-edited immune cells that will further contribute to other non–gas exchange functions of the lung.

Lung Assist Devices

ECMO devices have a significant role in short-term acute neonatal respiratory diseases and a more limited role in acute adult respiratory diseases. However, ECMO requires hospitalization in critical care units and specialized health care providers and has a number of significant complications including inflammation and clotting (79, 80). As such, it is not a practical or cost-effective option for long-term bridging to lung transplant or for use in patients with end-stage COPD or other lung diseases and who will not qualify for transplant. Despite some limited technologic advances (81, 82), new innovative, cost-effective, easily implementable technologies are desperately needed. Developments in wearable portable artificial lungs (83) or consideration of decellularized avian lungs recellularized with mammalian lung cells (avian lung assist device) (84) demonstrate the wide ranging potential of and further room for novel and innovative engineered devices.

Summary

A number of regenerative medicine approaches for lung diseases are in active development and offer hope for patients with COPD and other lung diseases. However, none has yet reached fruition and despite promise, care has to be taken to deliver an accurate and consistent message to patients and their families to minimize the growing influence of stem cell medical tourism for COPD and other lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kaiser LR. The future of multihospital systems. Top Health Care Financ. 1992;18:32–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao JT, Goldin JG, Dermand J, Ibrahim G, Brown MS, Emerick A, et al. A pilot study of all-trans-retinoic acid for the treatment of human emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:718–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2106123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Fang Q, Kim H. Preclinical studies of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) administration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broekman W, Khedoe PPSJ, Schepers K, Roelofs H, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. Mesenchymal stromal cells: a novel therapy for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Thorax. 2018;73:565–574. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dye BR, Dedhia PH, Miller AJ, Nagy MS, White ES, Shea LD, et al. A bioengineered niche promotes in vivo engraftment and maturation of pluripotent stem cell derived human lung organoids. eLife. 2016;5:e19732. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milman Krentsis I, Rosen C, Shezen E, Aronovich A, Nathanson B, Bachar-Lustig E, et al. Lung injury repair by transplantation of adult lung cells following preconditioning of recipient mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7:68–77. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murdock MH, Badylak SF. Biomaterials-based in situ tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2017;1:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikolić MZ, Rawlins EL. Lung organoids and their use to study cell–cell interaction. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0137-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horváth L, Umehara Y, Jud C, Blank F, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B. Engineering an in vitro air–blood barrier by 3D bioprinting. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7974. doi: 10.1038/srep07974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, Ingber DE. Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science. 2010;328:1662–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1188302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilpin SE, Wagner DE. Acellular human lung scaffolds to model lung disease and tissue regeneration. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27:180021. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0021-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moerer O, Vasques F, Duscio E, Cipulli F, Romitti F, Gattinoni L, et al. Extracorporeal gas exchange. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow–derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss DJ. Stem cells, cell therapies, and bioengineering in lung biology and diseases: comprehensive review of the recent literature 2010–2012. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:S45–S97. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201304-090AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loi R, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow–derived cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotton DN, Fabian AJ, Mulligan RC. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:328–334. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0175RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prockop DJ. The exciting prospects of new therapies with mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2017;19:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galipeau J, Sensébé L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam MN, Das SR, Emin MT, Wei M, Sun L, Westphalen K, et al. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat Med. 2012;18:759–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Z, Li F, Zhou X, Chung KF, Wang W, Wang J. Stem cell therapies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current status of pre-clinical studies and clinical trials. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:1084–1098. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shigemura N, Okumura M, Mizuno S, Imanishi Y, Nakamura T, Sawa Y. Autologous transplantation of adipose tissue–derived stromal cells ameliorates pulmonary emphysema. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2592–2600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shigemura N, Okumura M, Mizuno S, Imanishi Y, Matsuyama A, Shiono H, et al. Lung tissue engineering technique with adipose stromal cells improves surgical outcome for pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1199–1205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-406OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuhgetsu H, Ohno Y, Funaguchi N, Asai T, Sawada M, Takemura G, et al. Beneficial effects of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation against elastase-induced emphysema in rabbits. Exp Lung Res. 2006;32:413–426. doi: 10.1080/01902140601047633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhen G, Liu H, Gu N, Zhang H, Xu Y, Zhang Z. Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation protects against rat pulmonary emphysema. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3415–3422. doi: 10.2741/2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhen G, Xue Z, Zhao J, Gu N, Tang Z, Xu Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation increases expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in papain-induced emphysematous lungs and inhibits apoptosis of lung cells. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:605–614. doi: 10.3109/14653241003745888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman AM, Paxson JA, Mazan MR, Davis AM, Tyagi S, Murthy S, et al. Lung-derived mesenchymal stromal cell post-transplantation survival, persistence, paracrine expression, and repair of elastase-injured lung. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1779–1792. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huh JW, Kim SY, Lee JH, Lee JS, Van Ta Q, Kim M, et al. Bone marrow cells repair cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L255–L266. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsha AM, Ohkouchi S, Xin H, Kanehira M, Sun R, Nukiwa T, et al. Paracrine factors of multipotent stromal cells ameliorate lung injury in an elastase-induced emphysema model. Mol Ther. 2011;19:196–203. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweitzer KS, Johnstone BH, Garrison J, Rush NI, Cooper S, Traktuev DO, et al. Adipose stem cell treatment in mice attenuates lung and systemic injury induced by cigarette smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:215–225. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingenito EP, Tsai L, Murthy S, Tyagi S, Mazan M, Hoffman A. Autologous lung-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in experimental emphysema. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:175–189. doi: 10.3727/096368910X550233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Park MK, Huh JW, Ro JY, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell–conditioned media recovers lung fibroblasts from cigarette smoke-induced damage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L891–L908. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guan XJ, Song L, Han FF, Cui ZL, Chen X, Guo XJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells protect cigarette smoke–damaged lung and pulmonary function partly via VEGF–VEGF receptors. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:323–335. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Zhang Y, Yeung SC, Liang Y, Liang X, Ding Y, et al. Mitochondrial transfer of induced pluripotent stem cell–derived mesenchymal stem cells to airway epithelial cells attenuates cigarette smoke–induced damage. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:455–465. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0529OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antunes MA, Abreu SC, Cruz FF, Teixeira AC, Lopes-Pacheco M, Bandeira E, et al. Effects of different mesenchymal stromal cell sources and delivery routes in experimental emphysema. Respir Res. 2014;15:118. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tibboel J, Keijzer R, Reiss I, de Jongste JC, Post M. Intravenous and intratracheal mesenchymal stromal cell injection in a mouse model of pulmonary emphysema. COPD. 2014;11:310–318. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.854322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song L, Guan XJ, Chen X, Cui ZL, Han FF, Guo XJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reduce cigarette smoke–induced inflammation and airflow obstruction in rats via TGF-β1 signaling. COPD. 2014;11:582–590. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.898032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Gu C, Xu W, Yan J, Xia Y, Ma Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of amniotic fluid–derived mesenchymal stromal cells on lung injury in rats with emphysema. Respir Res. 2014;15:120. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu HM, Ma LJ, Wu JZ, Li YG. MSCs relieve lung injury of COPD mice through promoting proliferation of endogenous lung stem cells. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2015;35:828–833. doi: 10.1007/s11596-015-1514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu W, Song L, Li XM, Wang D, Guo XJ, Xu WG. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate airway inflammation and emphysema in COPD through down-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 via p38 and ERK MAPK pathways. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8733. doi: 10.1038/srep08733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim Y-S, Kim J-Y, Huh JW, Lee SW, Choi SJ, Oh YM. The therapeutic effects of optimal dose of mesenchymal stem cells in a murine model of an elastase induced-emphysema. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015;78:239–245. doi: 10.4046/trd.2015.78.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennelly H, Mahon BP, English K. Human mesenchymal stromal cells exert HGF dependent cytoprotective effects in a human relevant pre-clinical model of COPD. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38207. doi: 10.1038/srep38207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Zhang Y, Liang Y, Cui Y, Yeung SC, Ip MS, et al. iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells exert SCF-dependent recovery of cigarette smoke–induced apoptosis/proliferation imbalance in airway cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:265–277. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cappetta D, De Angelis A, Spaziano G, Tartaglione G, Piegari E, Esposito G, et al. Lung mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate elastase-induced damage in an animal model of emphysema. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:9492038. doi: 10.1155/2018/9492038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng Y, Gu W, Zhang G, Li X, Guo X. Activation of Notch1 signaling alleviates dysfunction of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells induced by cigarette smoke extract. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3133–3147. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S146201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karagiannis K, Proklou A, Tsitoura E, Lasithiotaki I, Kalpadaki C, Moraitaki D, et al. Impaired mRNA expression of the migration related chemokine receptor CXCR4 in mesenchymal stem cells of COPD patients. Int J Inflam. 2017;2017:6089425. doi: 10.1155/2017/6089425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tura-Ceide O, Lobo B, Paul T, Puig-Pey R, Coll-Bonfill N, García-Lucio J, et al. Cigarette smoke challenges bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell capacities in guinea pig. Respir Res. 2017;18:50. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0530-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barwinska D, Traktuev DO, Merfeld-Clauss S, Cook TG, Lu H, Petrache I, et al. Cigarette smoking impairs adipose stromal cell vasculogenic activity and abrogates potency to ameliorate ischemia. Stem Cells. 2018;36:856–867. doi: 10.1002/stem.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng SL, Lin CH, Yao CL. Mesenchymal stem cell administration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: state of the science. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:8916570. doi: 10.1155/2017/8916570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss DJ, Casaburi R, Flannery R, LeRoux-Williams M, Tashkin DP. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of mesenchymal stem cells in COPD. Chest. 2013;143:1590–1598. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stolk J, Broekman W, Mauad T, Zwaginga JJ, Roelofs H, Fibbe WE, et al. A phase I study for intravenous autologous mesenchymal stromal cell administration to patients with severe emphysema. QJM. 2016;109:331–336. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Oliveira HG, Cruz FF, Antunes MA, de Macedo Neto AV, Oliveira GA, Svartman FM, et al. Combined bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cell therapy and one-way endobronchial valve placement in patients with pulmonary emphysema: a phase I clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:962–969. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armitage J, Tan DBA, Troedson R, Young P, Lam KV, Shaw K, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell infusion modulates systemic immunological responses in stable COPD patients: a phase I pilot study. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1702369. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02369-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dominici M, Nichols K, Srivastava A, Weiss DJ, Eldridge P, Cuende N, et al. 2013–2015 ISCT Presidential Task Force on Unproven Cellular Therapy. Positioning a scientific community on unproven cellular therapies: the 2015 International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1663–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marks P, Gottlieb S. Balancing safety and innovation for cell-based regenerative medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:954–959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1715626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ikonomou L, Freishtat RJ, Wagner DE, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Weiss DJ. The global emergence of unregulated stem cell treatments for respiratory diseases: professional societies need to act. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1205–1207. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-277ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikonomou L, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Wagner DE, Freishtat RJ, Weiss DJ American Thoracic Society Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology Assembly Stem Cell Working Group. Unproven stem cell treatments for lung disease: an emerging public health problem. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:P13–P14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.1957P13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagner DE, Turner L, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Weiss DJ, Ikonomou L. Co-opting of ClinicalTrials.gov by patient-funded studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:579–581. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30242-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zacharias WJ, Frank DB, Zepp JA, Morley MP, Alkhaleel FA, Kong J, et al. Regeneration of the lung alveolus by an evolutionarily conserved epithelial progenitor. Nature. 2018;555:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature25786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hynds RE, Bonfanti P, Janes SM. Regenerating human epithelia with cultured stem cells: feeder cells, organoids and beyond. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:139–150. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201708213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan Q, Choi KM, Sicard D, Tschumperlin DJ. Human airway organoid engineering as a step toward lung regeneration and disease modeling. Biomaterials. 2017;113:118–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson DC, Mellody M, Meneses LK, Hope AC, Dunn B, Gomperts BN. Development of a three-dimensional bioengineering technology to generate lung tissue for personalized disease modeling. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2018;46:e56. doi: 10.1002/cpsc.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jamróz W, Szafraniec J, Kurek M, Jachowicz R. 3D printing in pharmaceutical and medical applications: recent achievements and challenges. Pharm Res. 2018;35:176. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2454-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fishman JM, Wiles K, Lowdell MW, De Coppi P, Elliott MJ, Atala A, et al. Airway tissue engineering: an update. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:1477–1491. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.938631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bae SW, Lee KW, Park JH, Lee J, Jung CR, Yu J, et al. 3D bioprinted artificial trachea with epithelial cells and chondrogenic-differentiated bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E1624. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hawkes N. Macchiarini case: seven researchers are guilty of scientific misconduct, rules Karolinska’s president. BMJ. 2018;361:k2816. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nawroth JC, Barrile R, Conegliano D, van Riet S, Hiemstra PS, Villenave R. Stem cell–based lung-on-chips: the best of both worlds? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E1624. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guenat OT, Berthiaume F. Incorporating mechanical strain in organs-on-a-chip: lung and skin. Biomicrofluidics. 2018;12:042207. doi: 10.1063/1.5024895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner DE, Bonvillain RW, Jensen T, Girard ED, Bunnell BA, Finck CM, et al. Can stem cells be used to generate new lungs? Ex vivo lung bioengineering with decellularized whole lung scaffolds. Respirology. 2013;18:895–911. doi: 10.1111/resp.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Price AP, England KA, Matson AM, Blazar BR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A. Development of a decellularized lung bioreactor system for bioengineering the lung: the matrix reloaded. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2581–2591. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petersen TH, Calle EA, Zhao L, Lee EJ, Gui L, Raredon MB, et al. Tissue-engineered lungs for in vivo implantation. Science. 2010;329:538–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1189345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ott HC, Clippinger B, Conrad C, Schuetz C, Pomerantseva I, Ikonomou L, et al. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat Med. 2010;16:927–933. doi: 10.1038/nm.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cortiella J, Niles J, Cantu A, Brettler A, Pham A, Vargas G, et al. Influence of acellular natural lung matrix on murine embryonic stem cell differentiation and tissue formation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2565–2580. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Platz J, Bonenfant NR, Uhl FE, Coffey AL, McKnight T, Parsons C, et al. Comparative decellularization and recellularization of wild-type and α-1,3 galactosyltransferase knockout pig lungs: a model for ex vivo xenogeneic lung bioengineering and transplantation. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2016;22:725–739. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2016.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou H, Kitano K, Ren X, Rajab TK, Wu M, Gilpin SE, et al. Bioengineering human lung grafts on porcine matrix. Ann Surg. 2018;267:590–598. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sokocevic D, Bonenfant NR, Wagner DE, Borg ZD, Lathrop MJ, Lam YW, et al. The effect of age and emphysematous and fibrotic injury on the re-cellularization of de-cellularized lungs. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3256–3269. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wagner DE, Bonenfant NR, Parsons CS, Sokocevic D, Brooks EM, Borg ZD, et al. Comparative decellularization and recellularization of normal versus emphysematous human lungs. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3281–3297. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jacob A, Morley M, Hawkins F, McCauley KB, Jean JC, Heins H, et al. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into functional lung alveolar epithelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:472–488.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Happle C, Lachmann N, Ackermann M, Mirenska A, Göhring G, Thomay K, et al. Pulmonary transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived macrophages ameliorates pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:350–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1562OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Squiers JJ, Lima B, DiMaio JM. Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in adults: fundamental principles and systematic review of the evidence. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Douflé G, Ferguson ND. Monitoring during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:230–238. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arazawa DT, Kimmel JD, Finn MC, Federspiel WJ. Acidic sweep gas with carbonic anhydrase coated hollow fiber membranes synergistically accelerates CO2 removal from blood. Acta Biomater. 2015;25:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoganson DM, Gazit AZ, Boston US, Sweet SC, Grady RM, Huddleston CB, et al. Paracorporeal lung assist devices as a bridge to recovery or lung transplantation in neonates and young children. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Madhani SP, Frankowski BJ, Burgreen GW, Antaki JF, Kormos R, D’Cunha J, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a novel integrated wearable artificial lung. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wrenn SM, Griswold ED, Uhl FE, Uriarte JJ, Park HE, Coffey AL, et al. Avian lungs: a novel scaffold for lung bioengineering. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.