Abstract

Objective

We conducted a meta-analysis to examine (1) the time-course of response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), (2) whether higher doses of SSRIs are associated with an improved response in pediatric OCD, (3) differences in efficacy between SSRI agents; (4) differences in efficacy between SSRIs and clomipramine and (5) whether the time-course and magnitude of response to SSRIs are different in pediatric and adult patients with OCD.

Method

We searched PubMed and CENTRAL for randomized controlled trials comparing SSRIs (or clomipramine) to placebo for the treatment of pediatric OCD and using the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale as an outcome. We extracted weekly symptom data from trials in order to characterize the trajectory of pharmacological response to SSRIs. Pooled estimates of treatment effect were calculated based on weighted mean differences between treatment and placebo group.

Results

Nine trials involving 801 children with OCD were included in this meta-analysis. A logarithmic model indicating the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment best fit the longitudinal data for both clomipramine and SSRIs. Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared to placebo than SSRIs. There was no evidence for a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data was limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time-course of response to SSRIs in OCD.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the greatest incremental treatment gains in pediatric OCD occur early in SSRI treatment (similar to adults with OCD and children and adults with major depression).

Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, meta-analysis, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, clomipramine

Introduction

Over the past three decades, we have made advances in the pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in both adult and pediatric populations. Meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials in adults with OCD suggest the superiority of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine compared to placebo.1-8 Clomipramine appears to have a larger effect size than SSRI medications when compared to placebo in meta-analyses of adults with OCD.1-8 Nonetheless, clomipramine is not to be considered the first-line pharmacotherapy for OCD because of its poor side-effect profile compared to SSRIs.9-11 Multiple randomized, placebo-controlled trials have been conducted in children with OCD. A landmark meta-analysis revealed similar efficacy regarding serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the pharmacotherapy of children with OCD compared to adults.12 This meta-analysis found that SSRIs and clomipramine were significantly more effective than placebo in treating children with OCD and that clomipramine trials demonstrated a larger effect size than SSRI trials when compared to placebo.12 SSRIs are currently a first-line treatment for OCD along with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).13-15 CBT is currently recommended for children with mild to moderate OCD.13

Several aspects of current OCD pharmacological treatment guidelines have been well supported by data in adults with OCD: (1) high-dose SSRI treatment is marginally more effective than low-dose treatments (2) a proper trial of an SSRI medication is 2-3 months and (3) antipsychotic augmentation is effective in treatment-refractory OCD.16,17 However, these guidelines have largely been adopted for children with OCD without evidence specific to pediatric populations. The objective of this meta-analysis is to examine weekly treatment data in pediatric OCD pharmacotherapy trials in order to (1) examine the time frame and magnitude of treatment response to SSRIs and clomipramine in children; (2) clarify if high doses of SSRIs are more effective than low doses in children with OCD; (3) examine potential differences in efficacy between individual SSRI agents and (4) examine differences in measured efficacy between SSRIs and clomipramine. We will then compare the data in children and adults to determine if the pattern of response to SSRIs is indeed similar between the two age groups. A previous meta-analysis using a similar set of included trials has already demonstrated (1) a greater measured efficacy of clomipramine as compared to SSRIs in placebo-controlled trials and (2) no difference in measured efficacy between different SSRI agents in children with OCD. We will replicate and extend upon the findings in that meta-analysis by comparing these agents using longitudinal data from each trial.

Method

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Eligible trials were searched using the search terms “Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors”[Mesh] OR “Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors” [Pharmacological Action] AND “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” [Mesh] on PubMed on May 22, 2013. Results were limited to randomized controlled trials. The reference lists of relevant SSRI meta-analyses on adults were also searched for additional citations of potential trials.2,16 From this extensive list, trials were selected on the basis that they were done in children and adolescents. To be included in this meta-analysis, trials had to (1) be randomized; (2) be double-blinded; (3) compare SSRIs or clomipramine to placebo; (4) measure OCD using Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) or change in CY-BOCS over weekly time points18-20 and (5) involve children and/or adolescents in the study population. Henceforth, clomipramine and SSRIs (otherwise known as serotonergic reuptake inhibitors) will be referred to SRIs. Trials were excluded if they (1) did not study OCD; (2) did not examine the efficacy of an SRI; (3) did not include a placebo comparison group; (4) did not use CY-BOCS scales; (5) included adults in the treatment population; (6) provided adjunctive behavioral therapy concurrently to pharmacological treatment; (7) were discontinuation trials. We used CY-BOCS as the exclusive outcome measure, as this measure has been routinely utilized as the primary outcome of SSRI trials in pediatric OCD, and limited longitudinal data was likely to be available for any other rating scale. Selection criteria for and characteristics of adult OCD trials used in comparison are similar and are described in depth elsewhere.21

Data Extraction

Included trials provided weekly data points reported in CY-BOCS or change in CY-BOCS with a given SRI.22-30 Some trials explicitly reported the weekly values in a table,24,27,30 while others provided a graph of CY-BOCS scores or change in CY-BOCS over time.22-26, 28-30 A computer program (Dexter; German Astrophysical Virtual Observatory, University of Heidelberg, Germany) was used to extract weekly data points from these graphs. Dexter is a computer program that allows for accurate data extraction from figures by defining length and scale of x- and y-axes and then assigning values to selected data points on this scale. In order to verify the inter-rater reliability of the extraction technique, we had two investigators blindly extract the data included in this meta-analysis. For the 400 data points included in this meta-analysis (weekly CY-BOCS scores for 8 included trials), only 3 out of the 400 values extracted (CY-BOCS ratings) differed by greater than 1%. The average % difference in CY-BOCS scores extracted between the two raters was 0.4%. Only 1% of all extracted values differed by greater than 0.2 of a CY-BOCS point between the two extractors.

Additional data was collected on type of medication utilized, maximum dosage of medication, duration of trial, number of recruitment sites, publication year, and year that recruitment was started. All medication doses were transformed into imipramine- (or clomipramine-) equivalent doses using previously described methodology.31

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis for this trial was adapted from a previously published meta-analysis examining the response curve of SSRIs for major depression and OCD.21,32 All analyses were conducted using the statistical software program SAS 9.2 and Microsoft Excel 2007. For each trial at each available weekly time point (up to week 12), we calculated weighted mean difference (WMD) for the difference in CY-BOCS improvement between the medication and placebo group. Weighted mean difference can be interpreted as the true treatment effect of SSRIs and is calculated as the difference (SSRI-placebo) in CY-BOCS score at a given time point.33 We used generalized estimating equations to examine the effects of trial and treatment, modeling different forms of the treatment effect (see tested models below), accounting for different periods within trials as repeated measures, and defining a new covariance structure for each trial as a random effect (see reference 32 for further details on methodology). Each trial's point estimate of WMD was weighted by the number of randomized patients in that trial.

Treatment effects were described in models as (1) constant effect (2) ramp effect (3) square root effect (4) constant and ramp effect (5) logarithmic effect and (6) exponential effect. An autoregressive variance function was then used, and best-fitting models for clomipramine and SSRIs were selected separately using the Aikaike information criterion.32 For the primary analysis, SSRI and clomipramine trials were analyzed separately. We also ran the same analyses examining the improvement from baseline in CY-BOCS in the placebo and SSRI treatment groups as outcomes. The shape of the response curve for the true treatment effect of SSRIs (SSRI improvement- placebo improvement) may differ from the actual improvement in the SSRI or placebo groups that includes other non-specific effects such as natural course and variation in the disease, regression towards the mean, other time effects and unidentified parallel interventions.33

Once the best-fitting model of response trajectory was established for WMD, we examined several additional questions in secondary analyses to examine the effects of salient trial features on the response curves to SRIs in pediatric OCD. Specifically, we examined the effects of type of SSRI (e.g. fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine), SSRI dosage, year of trial publication, start date of trial recruitment, and number of trial recruitment sites. The measured efficacy of antidepressant medications in pediatric depression has been previously demonstrated to be associated with publication year and number of recruitment sites.34,35 Participants with OCD enrolling in later trials were also less likely to be treatment naïve and more likely to have greater diagnostic complexity. In these models we added both a main effect of the variable of interest and an interaction between the variable of interest and study week in the models. If main effects were non-significant, they were eliminated from the model (as the variables of interest were unlikely to cause significant differences between medication and placebo at baseline). When examining the effects of dose, we additionally examined models taking into account the possibility that the effect of dose would be delayed (as it typically takes 2-4 weeks to titrate to the maximum SSRI dose in OCD trials). We explored dose effects that started at baseline, week 2, week 4, or week 6 by adding a main effect of a dummy variable indicating whether the time point was greater than or equal to the week of interest and added that dummy variable to the interaction term to indicate at what point that term would contribute to the model. We additionally examined the difference in response curves between (1) SSRIs and clomipramine in children and (2) SSRIs in children and adults using similar methodology. We compared to the efficacy of SSRIs in children to previously collected similar data in a recent meta-analysis of adults.21 Methodology for selection and analysis of adult SSRI OCD trials were nearly identical to that performed in this meta-analysis, except adult trials were included and trials involving children were excluded.21

Results

Included Trials

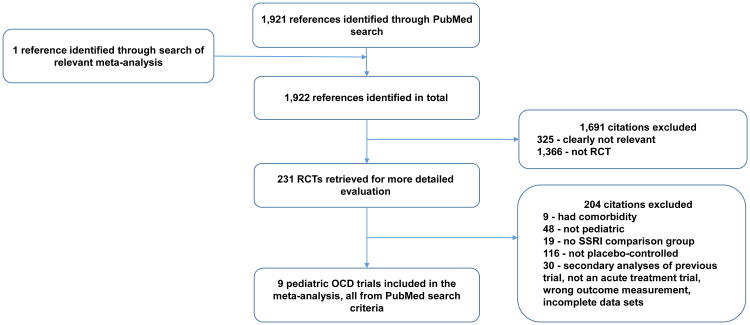

Figure 1 depicts the procedure for selection of trials. We identified 9 trials of SRIs involving 801 children and adolescents that were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis. Table 1 depicts the characteristics of included trials. Seven trials examined efficacy of SSRIs, and 2 trials examined the efficacy of clomipramine. Only 4 different SSRIs have been studied in placebo-controlled trials in children: fluvoxamine (k=1, n= 120), fluoxetine (k=3, n= 159), paroxetine (k=1, n=203), and sertraline (k=2, n=243). Table S1 (available online) describes the characteristics of trials of SSRIs utilized in the adult comparison group.21

Figure 1.

Selection of studies. Note: OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Table 1. Characteristics of 9 Randomized, Controlled Trials Used in a Meta-Analysis of Pharmacotherapy Responses Over Time for Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

| Author | Year | Na | Medication | Doseb | Imipramine Dose Equivalent (mg) | Duration | Titration schedule | Number of Sites | Industry (I) or Publically Funded (P) | Recruitment start year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March29 | 1990 | 16 | Clomipramine | 200 | 240 | 10 | Initial dose 25mg for 4 days then 25mg BID for 3 days then flexible titration | 1 | I | Not reported |

| Riddle30 | 1992 | 13 | Fluoxetine | 20 | 100 | 8 | Fixed 20mg dose | 1 | P | 1988 |

| DeVeaugh-Geiss23 | 1992 | 60 | Clomipramine | 200 | 200 | 8 | Initial dose 25mg for 4 days titrated to 75-100mg by end of week 2 then flexible titration | 5 | I | 1991 |

| March28 | 1998 | 187 | Sertraline | 200 | 240 | 12 | Minimum starting dose was 25 mg. Increased by 50 mg weekly to maximum daily dose by week 4 | 12 | I | 1991 |

| Riddle 22 | 2001 | 120 | Fluvoxamine | 200 | 200 | 10 | Starting dose 25 mg. Increased by 25 mg every 3 or 4 days to maximum daily dose of 200 mg by week 3 | 17 | I | 1991 |

| Geller25 | 2001 | 103 | Fluoxetine | 60 | 300 | 13 | Initial dose 10 mg daily, increased to 20 mg daily by week 3. Flexible dosing thereafter. | 21 | I | 1999 |

| Liebowitz27 | 2002 | 43 | Fluoxetine | 80 | 400 | 16 | Initial dose 20 mg, increased to 40 mg daily at week 3 and 60mg daily at week 5, possible further titration to 80mg after week 6. | 2 | I/P | 1991 |

| Geller26 | 2004 | 203 | Paroxetine | 50 | 250 | 10 | Initial dose 10mg daily, increased in 10mg increments every week to maximal dose. | 36 | I | 2000 |

| POTS study24 | 2004 | 56 | Sertraline | 200 | 240 | 12 | Initial dose 25 mg/daily, increased in 25mg increments to maximum dose by week 6 | 3 | P | 1997 |

Note: CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale; SSRI = Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor.

Maximum number of participants randomized to either an SSRI or placebo group in the respective study. Participants randomized to non-SSRI treatment groups were not included in this total estimate.

Represents the fixed dose or maximum dose to which a study medication was titrated if study had flexible dosing regimen.

Time Course of SSRI Response in Pediatric OCD compared to Placebo

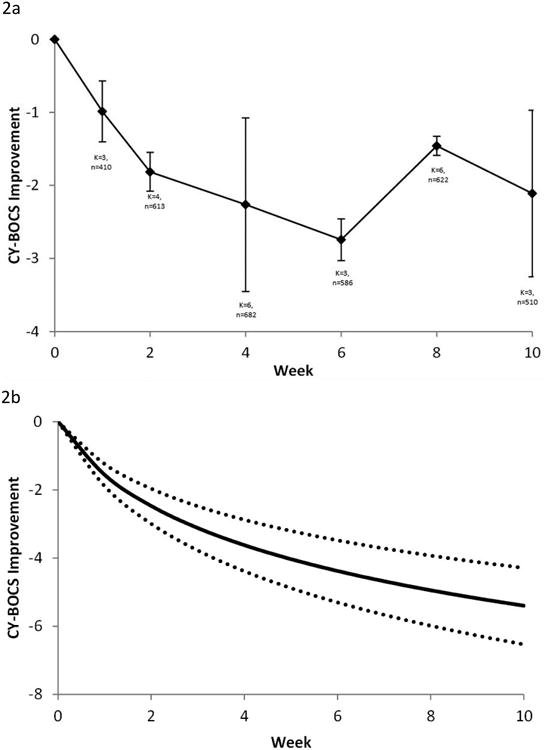

Overall, seven trials with a total of 725 participants (placebo: n= 351 and SSRI: n=374) provided data for analysis across multiple weekly points to assess the trend of OCD symptom improvement (Table 1). The actual (pooled) weighted mean differences in CY-BOCS scores per week for all SSRI trials is shown in Figure 2A. A significant benefit of SSRI compared to placebo was observed as early as 2 weeks after the initiation of treatment in pediatric OCD. Over 85% of the improvement observed on SSRI compared to placebo in pediatric OCD trials was observed by week 2.

Figure 2.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Differences in CY-BOCS ratings across time between patients treated with SSRIs and placebo. A) Weighted mean difference in CY-BOCS between SSRIs and placebo at time points. Error bars represent standard error. B) Best-fit model (logarithmically decreasing treatment response) for the weighted mean difference between groups. Dotted lines represent 95% CIs.

Based on the Aikaike information criterion, the best fitting model for treatment response to SSRIs was a logarithmic model. A logarithmic model indicates that improvement in OCD symptoms compared to placebo was greatest initially, and the rate of improvement compared to placebo declined over successive weeks. The estimate of treatment effect for SSRIs compared to placebo in the best-fitting logarithmic model was 2.25 (95% CI: 1.79-2.72); p<.001. The best-fitting treatment response curve of SSRIs vs. placebo in pediatric OCD over time is shown in Figure 2B.

The logarithmic model was significantly better than the alternative models with a constant and ramp effect (χ2=8.8, p<.001), a constant effect (χ2=23.2, p<.001), a ramp effect (χ2=30.5, p<.001), and an exponential effect (χ2=61.8, p<.001). The logarithmic model had a better fit than model with a square root function (χ2=1.7, p=.19), but not to a statistically significant degree. A model using a square root transformation of week is associated with a similar decreasing treatment effect with time as the logarithmic model.

Logarithmic models also provided the best fit for describing the improvement from baseline in CY-BOCS in the placebo and SSRI treatment groups. Figure 2C provides data from meta-analysis of individual time point data in placebo and SSRI treatment groups, and Figure 2D depicts the best-fit model for improvement in CY-BOCS from baseline in each group.

Effects of Different SSRI Agents

Models failed to demonstrate any significant differences between individual SSRI agents, consistent with previous literature.12 There was no significant difference between fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, and paroxetine.

Effect of SSRI Dose

Meta-analysis demonstrated no effect of maximum SSRI dosing on therapeutic response in pediatric OCD. In the best fit model, there was neither a significant effect of time or of the interaction of dose with time (log[week+]=0.-40 [95%CI: -3.48-2.67], p=.79; interaction=0.005 [95%CI: -0.007-0.017], p=.38). Figure S1 (available online) depicts the non-significant improvement in SSRI response with maximum titrated dosing in pediatric OCD. Models in which the effects of SSRI dose were delayed did not improve the overall fit of the model.

Effect of Publication Year

Later publication year was associated with significantly decreasing treatment effect of SSRI compared to placebo. There was a significant effect of time and interaction between time and publication year in the best fit model (interaction=-0.22 [95% CI: -0.41 to -0.03]; p=.02; log[week+1]=444 [95% CI: 64-824] p=.02). Benefits of SSRIs compared to placebo became negligible in trials published towards the end of the date range of SSRI trials for pediatric OCD. Figure S2A (available online) depicts the declining measured efficacy of SSRIs compared to placebo by publication year.

Effect of Trial Start Date

Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant association between recruitment start date and measured efficacy of SSRI pharmacotherapy (interaction= -0.12 [95% CI: -0.24 to 0.01]; p=.06; loge[week+1]=237 [95%CI: -20 to 494], p=.06) (Figure S2B, available online). However, there was a trend towards trials with a later recruitment start date demonstrating smaller benefits of SSRIs (p=.06).

Effect of Number of Trial Sites

The number of recruitment sites in pediatric SSRI trials was not significantly associated with measured treatment effects of SSRIs compared to placebo (interaction = 0.006 [95% CI: -0.05 to 0.06]; p = .8; log[week+1] = 0.79 [95% CI: -0.38 to 1.98]; p = .17).

Comparison of SSRI Response in Children Compared to Adults with OCD

Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference between SSRI response in children and adults with OCD. The best-fit model indicated a significant effect of time (log [week+1] = 1.33 [95% CI: 1.13 to 1.54]; p<.0001) and children demonstrated a lesser response compared to adults, but not to a statistically significant degree (interaction=-0.41[95% CI: -0.93 to 0.1]; p=.11). Figure S3 (available online) depicts the SSRI response compared to placebo in adults and children with OCD.

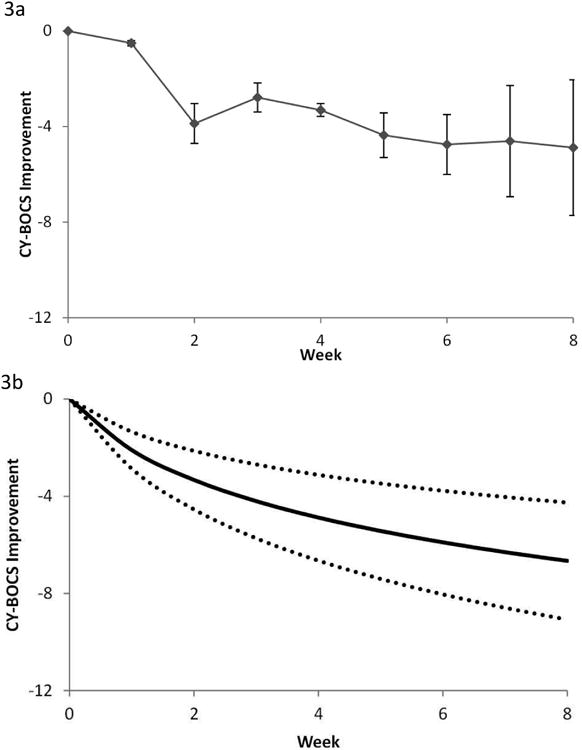

Time Course of Clomipramine Response in Pediatric OCD Compared to Placebo

Overall, only 2 trials with a total of 76 participants (placebo n= 37, clomipramine n= 39) provided data for analysis across multiple weekly points to assess OCD symptom improvement using clomipramine. The actual (pooled) weighted mean differences in CY-BOCS scores per week for all clomipramine trials is shown in Figure 3A. Over 75% of the improvement in OCD symptoms observed with clomipramine compared to placebo in pediatric OCD trials was evident by 2 weeks.

Figure 3.

Clomipramine response in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Differences in Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) ratings across time between patients treated with clomipramine and placebo. A) Weighted mean difference in CY-BOCS between clomipramine and placebo at time points. Error bars represent standard error. B) Best-fit model (logarithmically decreasing treatment response) for the weighted mean difference between groups. Dotted lines represent 95% CIs. These figures are based on data from 2 studies involving 76 participants.

Based on the Aikaike information criterion, the logarithmic model remained the best fit model. A logarithmic model indicates that improvement as measured by a change in CY-BOCS was greatest initially, followed by a declining rate of improvement in successive weeks. The root effect model, which also models a decreasing treatment effect with time, did not separate statistically from the logarithmic model (χ2=1.6, p=.2). A model with a constant and ramp effect (χ2=1.8, p=.17) also did not statistically separate from the logarithmic model. The logarithmic model had a significantly better fit than the constant effect (χ2=3.8, p=.05), the ramp effect (χ2=15.6, p<.0001), and an exponential effect (χ=32.5, p<.0001) models. The best fitting treatment response curve comparing clomipramine to placebo over time is shown in Figure 3B (log [week+1]=3.03 [95% CI: 1.94 to 4.13], p<.0001).

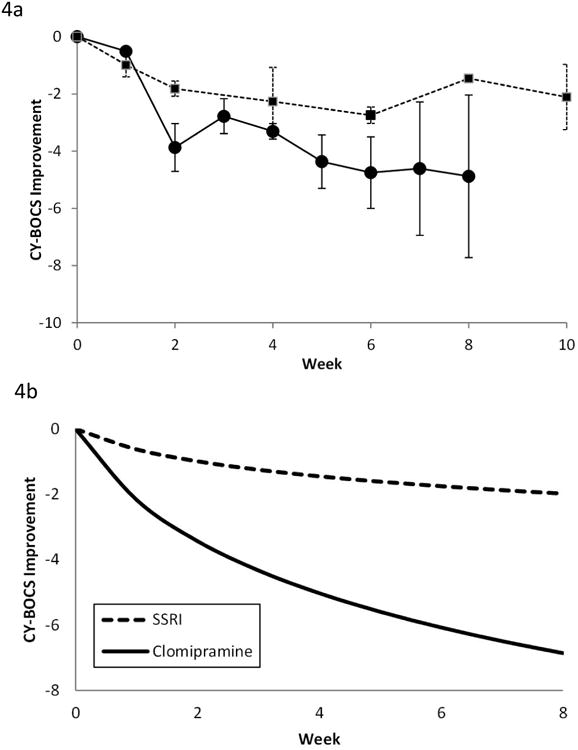

Comparison of Treatment Effect of Clomipramine to SSRIs in Children with OCD

Meta-analysis demonstrated a large and statistically significant difference favoring clomipramine compared to SSRIs. In the model there was a significant effect of time on the improvement in OCD symptoms experienced on both medications compared to placebo (log[week+1]=0.90 [95% CI: 0.38-1.41], p= .001) and a significantly larger effect of clomipramine compared to SSRI (interaction=2.22 [95%CI: 0.4-4.03], p=.01). Figure 4A depicts the actual improvement of pediatric participants with OCD on clomipramine and SSRIs relative to placebo. Figure 4B depicts the best fit model of the comparative efficacy of clomipramine and SSRIs relative to placebo.

Figure 4.

Comparison of clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: A) Comparison of weighted mean difference in Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) of clomipramine and SSRIs when compared to placebo at time points. Error bars represent standard error. Clomipramine response is depicted with a solid line. SSRI response is depicted with a dotted line. B) Best-fit model (logarithmically decreasing treatment response) for the weighted mean difference between SSRIs and clomipramine compared to placebo. Clomipramine was associated with a significantly greater treatment effect than SSRIs.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis demonstrated several important findings in the pharmacotherapy of pediatric OCD: (1) benefit from SSRIs and clomipramine was greatest in the first few weeks of treatment in pediatric OCD and was minimal after the 6th week of treatment similar to the SSRI response pattern observed in depression32,36; (2) there were no significant differences in magnitude of response to serotonergic medications between children and adults with OCD; (3) there were no significant differences in treatment responses between SSRI agents; but (4) clomipramine demonstrated a significantly greater response when compared to placebo than SSRIs; and (5) there is no evidence for increased benefit with higher maximum dosages of SSRIs as compared to lower maximum dosages in the pediatric OCD trials.

Previous meta-analyses of SSRIs in adults with OCD demonstrated a significant dosing effect of SSRIs, demonstrating that higher doses of SSRIs were associated with a significantly greater therapeutic response.16,21 We did not replicate this finding in children. Higher doses of SSRIs were associated with a marginally and not statistically significantly increased SSRI response in pediatric OCD. We believe that the lack of dosing effect seen in children with OCD may be attributable to the design of trials and the paucity of trials in pediatric OCD. Pediatric OCD studies, in contrast to adult OCD trials, were performed to demonstrate a treatment benefit at the maximum tolerated dose of SSRIs rather than being fixed-dose finding trials that examined the efficacy of agents across multiple different dosing regimens. Six out of seven pediatric OCD trials examining SSRIs used near maximally recommended doses of SSRI medications. These six trials involved 98% of participants included in our meta-analysis examining SSRI efficacy. Also, there are very few pediatric OCD trials compared to the adult literature. Therefore, our meta-analysis had limited power to replicate the SSRI dosing effect observed in adult OCD trials in pediatric OCD. Another possibility is that there exists no dose response relationship for SSRIs in pediatric OCD. We similarly did not demonstrate a dose response relationship in pediatric depression.37 Reduced tolerability of high dose SSRI pharmacotherapy in children due to side-effects (possibly behavioral activation, irritability, anxiety, insomnia etc.) could explain the absence of a dosing effect.

Our meta-analysis also demonstrated a larger benefit of clomipramine than SSRIs when both agents were compared to placebo. Our finding of increased measured efficacy of clomipramine compared to SSRIs is consistent with several previous meta-analyses in children and adults with OCD.1,5,7,12 These results are not surprising given that the list of included trials in this meta-analysis is nearly identical to a previous meta-analysis in pediatric OCD with similar findings using endpoint data only.12 Despite this finding, there are several reasons to be skeptical that clomipramine is more effective than SSRIs for OCD. Specifically, clomipramine trials were performed earlier on likely less refractory pediatric patients with OCD, and this could account for much of the increased efficacy. When meta-analysis was restricted to examining SSRI agents, there was a significant relationship between measured efficacy of SSRIs and publication year (and a trend towards a significant association with trial start date), suggesting that there may be diminishing measured effects of serotoninergic agents with time. This result suggests that children enrolled in later pediatric OCD trials were more refractory to these medications. This result is not surprising considering that many families enrolled in later SSRI placebo-controlled trials would have previously failed to achieve symptom relief on other similar medications available by prescription. Clomipramine, by contrast, was the first effective agent available for OCD, and trials of this agent would have thus enrolled a study population completely naïve to serotonergic agents. Arguing against these explanations is that the benefit of clomipramine over SSRIs was still significant when publication year and/or dose were controlled for in the meta-analysis. Additionally, there is a more significant side-effect burden with clomipramine: weight gain, anticholinergic side effects, and arrhythmias.9-11 These side effects not only affect compliance but also decrease the effectiveness of blinding in trials (e.g. if the child has side-effects on the pill, both the family and the study investigator may be more likely to believe that the participant is on active medication). This additional bias in the clomipramine trials may inflate their estimates of efficacy. The definitive way to examine the relative efficacy of clomipramine and SSRIs would be through head-to-head trials, and thus far none of the few trials examining this issue demonstrated superiority of clomipramine.12 Nonetheless, regardless of the actual superiority of clomipramine over SSRIs in pediatric OCD, we would not recommend it as the first-line pharmacological treatment for OCD because of its poor tolerability. Additionally, current practice guidelines recommend using CBT monotherapy in mild-to-moderate pediatric OCD cases and combined (SSRI and CBT) treatment for more severe pediatric cases.13

There were several limitations to our meta-analysis, including the small number of placebo-controlled trials in OCD, which limited our ability or power to conduct some comparisons, especially when examining clomipramine. Furthermore, it is possible that the shape of response curve for SSRIs and clomipramine over time is in some way determined by the design of the trials that contributed the data. In particular, the user of last observation carried forward analysis to account for missing data, which has become standard in trials of pharmaceutical treatments for depression and was used in some of the trials in this study, could make a constant effect appear logarithmic. Also, the shape of the response curve was likely influenced by the varying titration schedules of included trials. Nonetheless, this limitation would not detract from the observation that the greatest incremental treatment gains were observed early in SRI pharmacotherapy. We also had limited ability to examine the dose effects of SSRI within pediatric populations due to the paucity of trials and the absence of fixed-dose ranging studies in the pediatric population. Many participants also did not receive the maximal possible dose administered in the trials. Additionally, the generalizability of the pediatric OCD clinical population (with exclusion for several psychiatric comorbidities) to the clinical population of pediatric OCD is unclear. Increased psychiatric comorbidity has been previously associated with poor treatment response to SSRIs in pediatric OCD.38 Lastly, uncontrolled, open-label extension phases of SSRIs for pediatric OCD have suggested that there may be continued long-term benefits of medication beyond the initial timeframe observed in randomized controlled trials.39 Using data from this meta-analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility that children with OCD may be some additional improvement in symptoms that occurs beyond the timeframe of the acute treatment trials.

This meta-analysis establishes that in pediatric OCD, SSRI treatment gains are greatest early in treatment and detectable statistically within 2 weeks after the initiation of medication. This logarithmic pattern of SSRI response is similar to that of children and adults with major depressive disorder32,37 and OCD.21 Current American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Practice Parameters in pediatric OCD define an adequate SRI trial as a minimum of 10 weeks in duration with at least 3 weeks at a maximum tolerated dose.15 The AACAP Practice Parameters are similar to the American Psychiatric Association guidelines and indicate that pharmacotherapy with SSRIs is first line (along with CBT) and should be continued for 8-12 weeks, including 4-6 weeks at a maximum tolerable dose.15 CBT is the preferred initial treatment option in children with mild to moderate OCD.15 The meta-analysis may possibly suggest that pharmacotherapy trials of 8-12 weeks may not be necessary and that if a child shows no improvement with SRI treatment, trial durations could potentially be shorter. However, before a change in guidelines is considered, there needs to be more OCD pharmacological research that focuses on the prognostic utility of early SSRI response data on individual patient outcomes. Previous adult studies have suggested that early improvement with SSRIs and clomipramine is associated with response in short-term trials.40,41 Additionally, more effective, evidence-based treatments for SRI-refractory pediatric patients with OCD are needed, as there is limited guidance for further treatments once SRIs and CBT prove unhelpful.14 Further research is needed to identify these novel agents.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Dose effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Each line represents separate isoquants in fluoxetine-equivalent SSRI doses. Meta-analysis demonstrated no effect of maximum SSRI dosing on therapeutic response in pediatric OCD. In the best fit model, there was neither a significant effect of time nor of the interaction of dose with time (log[week+]=0.-40 [95%CI: -3.48-2.67], p=.79; interaction=0.005 [95%CI: -0.007-0.017], p=.38). CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Figure S2: Effect of publication year and recruitment year. Note: Figure S2A depicts the association between publication year and measured efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications. Later publication year was associated with significantly decreasing treatment effect of SSRI compared to placebo. There was a significant effect of time and interaction between time and publication year in the best fit model (interaction=-0.22 [95% CI: -0.41 to -0.03]; p=.02; log[week+1]=443 [95% CI: 64.16-823.78] p=.02). Figure S2B depicts the relationship between trial start date and measured efficacy of SSRI medications. Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant association between recruitment start date and measured efficacy of SSRI pharmacotherapy (interaction= -0.11 [95% CI: -0.24 to 0.01]; p=.06; loge[week+1]=237 [95%CI: -19.7 to 494], p=.06). CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Figure S3: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response curve in children as compared to adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference between SSRI response in children and adults with OCD. The best fit model indicated a significant effect of time (log [week+1] = 1.33 [95% CI: 1.13 to 1.54]; p<.0001), and children demonstrated a lesser response compared to adults, but not to a statistically significant degree (interaction=-0.41[95% CI: -0.93 to 0.1]; p=.11). Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Table S1. Characteristics of 23 Randomized, Controlled Trials Used in a Meta-Analysis of Pharmacotherapy Responses Over Time for Adult Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder21

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation for their funding of medical student fellowship programs in child psychiatry at Yale University and Vermont that helped foster the authors initial meeting and collaboration.

Funding: Dr. Bloch gratefully acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (K23MH091240 and R25MH077823) and from the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024139), a component of the National Institutes of Health, and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Bloch also acknowledges support from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Patterson Foundation, and the Tourette Association of America.

Dr. Bloch has received grant or research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Tourette Association of America, NARSAD, and the Patterson Foundation. He has served as a consultant to Therapix Biosciences and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Varigonda and Mr. Jakubovski report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Anjali L. Varigonda, University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington.

Mr. Ewgeni Jakubovski, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, CT.

Dr. Michael H. Bloch, Yale Child Study Center and Yale University.

References

- 1.Stein DJ, Spadaccini E, Hollander E. Meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10:11–18. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, Oakley-Browne M. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001765. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001765.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccinelli M, Pini S, Bellantuono C, Wilkinson G. Efficacy of drug treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A meta-analytic review. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(4):424–443. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ, Henk HJ. Behavioral versus pharmacological treatments of obsessive compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacol. 1998;136:205–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Katzelnick DJ, Serlin RC. Efficacy and tolerability of serotonin transport inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:53–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130053006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox BJ, Swinson RP, Morrison B, Lee PS. Clomipramine, fluoxetine, and behavior therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1993;24:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(93)90043-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman DL, Greenland S. Multivariate meta-analysis of controlled drug studies for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:309–317. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a quantitative review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:44–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puig-Antich J, Perel JM, Lupatkin W, et al. Imipramine in prepubertal major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(1):81–89. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800130093012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puig-Antich J, Perel JM, Lupatkin W, et al. Plasma levels of imipramine (IMI) and desmethylimipramine (DMI) and clinical response in prepubertal major depressive disorder: a preliminary report. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1979;18(4):616–627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)62210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biederman J. Sudden death in children treated with a tricyclic antidepressant. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(3):495–498. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, et al. Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):1919–1928. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;51(1):98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloch MH, Storch EA. Assessment and management of treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015 Apr;54(4):251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Simpson HB. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7 Suppl):5–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF, Pittenger C. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:850–5. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Kelmendi B, Coric V, Bracken MB, Leckman JF. A systematic review: antipsychotic augmentation with treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;11(7):622–632. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;46(11):1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;46(11):1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, et al. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jun;36(6):844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Issari Y, Jakubovski E, Bartley CA, Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Meta-Analysis: Early Onset of Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e605–11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riddle MA, Reeve EA, Yaryura-Tobias JA, et al. Fluvoxamine for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:222–229. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Moroz G, Biederman J, et al. Clomipramine hydrochloride in childhood and adolescent obsessive-compulsive disorder--a multicenter trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geller DA, Hoog SL, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Fluoxetine treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 Jul;40(7):773–779. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geller DA, Wagner KD, Emslie G, et al. Paroxetine treatment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004 Nov;43(11):1387–1396. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000138356.29099.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liebowitz MR, Turner SM, Piacentini J, et al. Fluoxetine in children and adolescents with OCD: a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(12):1431–1438. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.March JS, Biederman J, Wolkow R, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1752–1756. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.March JS, Johnston H, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Greist JH. Do subtle neurological impairments predict treatment resistance to clomipramine in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1990;1(2):133–140. doi: 10.1089/cap.1990.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riddle MA, Scahill L, King RA, et al. Double-blind, crossover trial of fluoxetine and placebo in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollini P, Pampallona S, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Effectiveness of antidepressants. Meta-analysis of dose-effect relationships in randomised clinical trials. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:297–303. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Geddes JR, Bhagwagar Z. Early onset of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant action: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1217–23. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst E, Resch KL. Concept of true and perceived placebo effects. Bmj. 1995;311:551–553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7004.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung AH, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in youth depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(7):735–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reyes MM, Panza KE, Martin A, Bloch MH. Time-lag bias in trials of pediatric antidepressants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Coughlin C, Bloch MH. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Early Treatment Response of Selective-Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Pediatric Major Depressive Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:557–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Coughlin C, Bloch MH. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Early Treatment Responses of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Pediatric Major Depressive Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, et al. Impact of comorbidity on treatment response to paroxetine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: is the use of exclusion criteria empirically supported in randomized clinical trials? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:S19–29. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook EH, Wagner KD, March JS, et al. Long-term sertraline treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1175–81. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ackerman DL, Greenland S, Bystritsky A. Use of receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate predictors of response to clomipramine therapy. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32:157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Conceicao Costa DL, Shavitt RG, Castro Cesar RC, et al. Can early improvement be an indicator of treatment response in obsessive-compulsive disorder? Implications for early-treatment decision-making. J Psychiatric Res. 2013;47:1700–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Dose effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Each line represents separate isoquants in fluoxetine-equivalent SSRI doses. Meta-analysis demonstrated no effect of maximum SSRI dosing on therapeutic response in pediatric OCD. In the best fit model, there was neither a significant effect of time nor of the interaction of dose with time (log[week+]=0.-40 [95%CI: -3.48-2.67], p=.79; interaction=0.005 [95%CI: -0.007-0.017], p=.38). CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Figure S2: Effect of publication year and recruitment year. Note: Figure S2A depicts the association between publication year and measured efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications. Later publication year was associated with significantly decreasing treatment effect of SSRI compared to placebo. There was a significant effect of time and interaction between time and publication year in the best fit model (interaction=-0.22 [95% CI: -0.41 to -0.03]; p=.02; log[week+1]=443 [95% CI: 64.16-823.78] p=.02). Figure S2B depicts the relationship between trial start date and measured efficacy of SSRI medications. Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant association between recruitment start date and measured efficacy of SSRI pharmacotherapy (interaction= -0.11 [95% CI: -0.24 to 0.01]; p=.06; loge[week+1]=237 [95%CI: -19.7 to 494], p=.06). CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Figure S3: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) response curve in children as compared to adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Note: Meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference between SSRI response in children and adults with OCD. The best fit model indicated a significant effect of time (log [week+1] = 1.33 [95% CI: 1.13 to 1.54]; p<.0001), and children demonstrated a lesser response compared to adults, but not to a statistically significant degree (interaction=-0.41[95% CI: -0.93 to 0.1]; p=.11). Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale.

Table S1. Characteristics of 23 Randomized, Controlled Trials Used in a Meta-Analysis of Pharmacotherapy Responses Over Time for Adult Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder21