Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged adults. Yet, these populations are significantly underrepresented in research.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the literature for published reports describing recruitment and retention of individuals from underrepresented backgrounds in ADRD research or underrepresented participants' perspectives regarding ADRD research participation. Relevant evidence was synthesized and evaluated for quality.

Results

We identified 22 eligible studies. Seven studies focused on recruitment/retention approaches, all of which included multifaceted efforts and at least one community outreach component. There was considerable heterogeneity in approaches used, specific activities and strategies, outcome measurement, and conclusions regarding effectiveness. Despite limited use of prospective evaluation strategies, most authors reported improvements in diverse representation in ADRD cohorts. Studies evaluating participant views focused largely on predetermined explanations of participation including attitudes, barriers/facilitators, education, trust, and religiosity. Across all studies, the strength of evidence was low.

Discussion

Overall, the quantity and quality of available evidence to inform best practices in recruitment, retention, and inclusion of underrepresented populations in ADRD research are low. Further efforts to systematically evaluate the success of existing and emergent approaches will require improved methodological standards and uniform measures for evaluating recruitment, participation, and inclusivity.

Keywords: Dementia, Recruitment science, Recruitment and retention, Recruitment interventions, Disparities, Representation in research

Highlights

-

•

There is a limited evidence base to inform applied ADRD recruitment approaches.

-

•

Efforts to improve ADRD research inclusion vary widely in design and evaluation.

-

•

Methodological standards can help inform an applied science of ADRD recruitment.

1. Introduction

The fundamental goal of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer's disease is to prevent and effectively treat Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) by 2025 [1]. A central component of the primary strategy for advancing this goal is to expand clinical trials of interventions that target modifiable disease risk factors with the goal of slowing, delaying, or preventing disease onset and progression [1]. Achieving this goal among the populations most affected will be impossible if enrollment in ADRD research is not expanded, particularly among underrepresented populations, such as racial/ethnic minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status, who have traditionally been underincluded in ADRD research [2,3]. This review focuses on empiric reports of ADRD research recruitment and/or retention within underrepresented populations and the perspectives of these participants regarding ADRD research participation.

Although underrepresentation has resulted in variable estimates of disease risk and disparity [[4], [5], [6], [7]], ample evidence suggests that ADRD disproportionately impacts the same populations that are underrepresented and, in some cases, nearly absent from ADRD research. Dementia-specific health disparities are well documented among several racial/ethnic minority populations, particularly in terms of ADRD incidence, prevalence, diagnosis, disease progression, treatment response, and disease burden [3,5,8]. Modifiable rather than genetic factors plausibly account for these disparities, given that racial/ethnic minority status is a risk marker for multiple ADRD risk factors such as poorer quality of early-life education and undermanaged cardiovascular conditions [3].

It has also been challenging to adequately examine the contributions of distinct mechanistic pathways among racially and ethnically diverse populations, although illumination of mechanisms will be key to successful intervention and treatment. While great progress has been made in advancing our understanding of underlying pathology that contributes to the clinical symptoms of dementia [9], there is growing concern that these findings are not generalizable to underrepresented populations because of insufficient biological and physiological data from racial/ethnic minority populations [10]. In addition, while members of racial/ethnic minority groups are more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged, emerging evidence suggests that exposure to social disadvantage at both the individual and neighborhood level may increase risk for development of ADRD independent of race and ethnicity markers, highlighting the importance of diverse representation across socioeconomic and geographic strata as well as race/ethnic background in research [[11], [12], [13], [14]].

There is growing recognition of this “recruitment crisis” and its implications for addressing ADRD as a public health crisis [15]. However, despite the advancement in novel initiatives to improve outreach and recruitment, ADRD research inclusion rates for racial/ethnic minorities and other historically marginalized populations remain low [15,16]. Theoretical frameworks that contextualize behavior at an individual, network, and/or societal level [17,18] have been used to successfully model, predict, and improve health behaviors, including research participation, in a number of fields such as cardiovascular disease prevention [19], and participation in physical activity [20]. However, the availability and applicability of frameworks that inform recruitment or retention strategies and predict engagement with ADRD research remain unclear [[21], [22], [23]].

The use of developing and disseminating a philosophy, framework, and evidence base for addressing recruitment challenges was endorsed by the National Institute on Aging's recently proposed National Strategy for Research Recruitment and Participation in Alzheimer's and Related Dementias Clinical Research [24]. The strategy identifies core goals toward increasing capacity for improved ADRD research recruitment and highlights the need for an applied science of recruitment to empirically inform the development of best practices for improving recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in ADRD research. The current review aims to highlight priorities and next steps required to advance the science of recruitment for ADRD research by determining the breadth and strength of existing evidence. Specifically, we conducted a systematic review to identify, appraise, and synthesize available evidence for the recruitment and retention of study participants from underrepresented backgrounds, as well as studies reporting these participants' views regarding ADRD research participation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study protocol

We published an a priori study protocol on PROSPERO which details review question, search methodology, and procedures for article screening, review, and synthesis (CRD42019093828). The protocol followed methodological guidance on mixed evidence synthesis from the Cochrane Collaborative [25] (Supplementary Appendix A).

2.2. Search strategy

Following our protocol, we developed a search strategy in collaboration with a health sciences librarian. We searched MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL (EbscoHOST), and PsycINFO (Ovid) using key search terms (Supplementary Appendix B) for relevant studies published after January 1, 2010. This date was selected in consideration of the considerable changes in ADRD research foci, including a major shift toward biomarker-focused research [26], that occurred subsequent to the last systematic evaluation of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation which encompassed ADRD-specific literature [27]. Searches were conducted on March 16, 2018. Because search and MeSH terms are not well established in the recruitment sciences field, we used multiple search strategies (Supplementary Appendix B). We also conducted a manual citation search from all included studies, and of all studies identified through the search that discussed recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in ADRD research, some were excluded because they were not data driven.

2.3. Study selection

We included two types of published reports 1) those that examined research recruitment and/or retention of participants from underrepresented backgrounds in ADRD research and 2) studies that reported on these participants' views regarding ADRD research participation. Studies were screened for inclusion according to the following predetermined eligibility criteria:

-

•

Included individuals from underrepresented backgrounds, defined as members of a racial/ethnic minority group and/or individuals from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Because many studies examine minority participant groups in relation to nonminority groups, studies did not have to focus exclusively on participants from underrepresented backgrounds but had to report focusing on these groups in their approach.

-

•

Published in a peer-reviewed journal after 1/1/2010 and available in English.

-

•

Included primary study data of participant views or evaluation data related to recruitment/retention efforts indicated through systematic reporting of standardized and nonstandardized measures used to characterize success of various recruitment/retention strategies or participant perspectives.

We imported results from each search strategy into EndNote Desktop Software, where duplicate articles were removed. Article screening was conducted using Covidence Systematic Review Software [28] which randomly assigns reviewers to complete duplicate independent reviews, with disagreements being arbitrated by a third reviewer. Authors A.L.G.-B., Y.J., S.F.-B., L.M.B., and M.Z. screened articles. After a title/abstract screen, potentially eligible full-text articles were reviewed to determine eligibility. A postpublication retraction check was performed on included studies on January 11, 2019, revealing that no studies had been retracted after publication.

2.4. Data extraction

Two independent reviewers used standardized data-extraction templates developed from the review protocol, with a third reviewer rectifying areas of disagreement. For all studies, we extracted information regarding study design, participants, setting, study inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant information and sociodemographics, specific measurement instruments or scales used, and findings. For studies reporting on recruitment/retention, we also extracted information about the delivery, modality, frequency and duration, fidelity measures, and resource requirements of specified recruitment/retention approaches (Supplementary Appendix C).

2.5. Assessment of study quality

Two reviewers independently evaluated study quality using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, which classifies a study as being strong, moderate, or weak depending on the study's sample and selection strategy, the study design, confounders, data collection methods, and attrition [29] (Supplementary Appendix D). For qualitative studies, quality was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Qualitative Research [30] (Supplementary Appendix E). Disagreements were arbitrated by a third reviewer.

2.6. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using standardized methods for thematic synthesis of primary study findings outlined by Thomas and Harden [31]. After extraction of primary study data, each study's findings were analyzed and thematically categorized using Excel. The themes were then collated into tables from which patterns and conclusions were identified through independent, duplicate review. A meta-analysis was not attempted because of limited evidence base and substantial heterogeneity in study design, populations, and outcome measures.

3. Results

3.1. Database search results

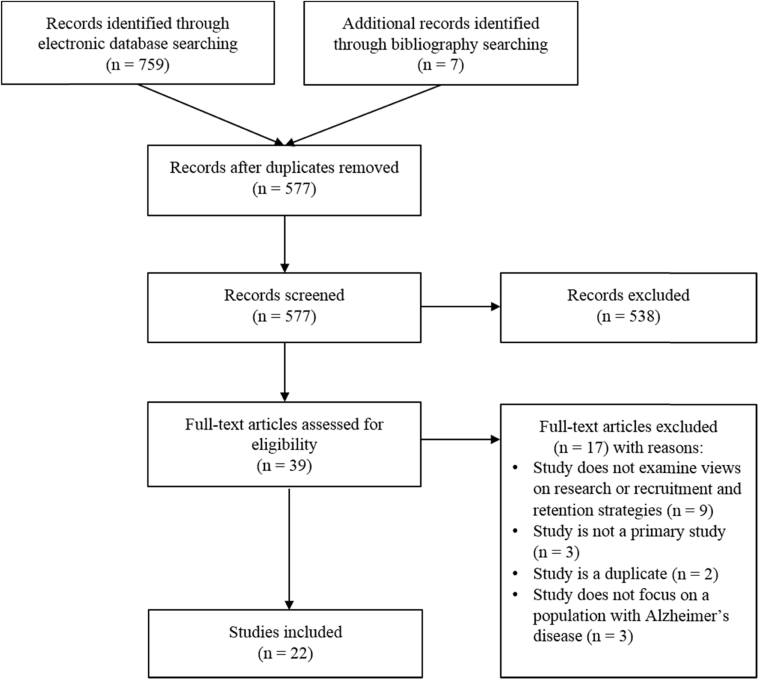

We identified 759 studies through database searches and seven through cross-referencing. After duplicates were removed, 577 studies remained, of which 538 were excluded by title and abstract screening. The remaining 39 studies were assessed for eligibility via full-text screening, 22 of which met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Study information, design, and population

| Study, year | Study aim | Study type or design | Study setting | Sample size | Target population | Does study report demographics? | Does study draw from existing cohort? | Does the study prospectively evaluate recruitment strategies by comparing multiple strategies or groups? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies evaluating recruitment approaches and views/attitudes | ||||||||

| Chao et al., 2011 [32] | To describe the efforts made to promote enrollment of Chinese Americans into research | Nonsystematic recruitment | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 453 | Chinese-American Elders | Yes | No |

|

| Studies evaluating one or more recruitment approaches | ||||||||

| Li et al., 2016 [33] | To evaluate the recruitment of elderly Chinese into clinical research through community lecture, newspaper, word-of-mouth, or clinical services | Outreach/community engagement approach, descriptive analysis | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 98 | Chinese-American Elders | Yes | No |

|

| Morrison et al., 2016 [34] | To evaluate the yield and cost of three recruitment approaches—direct mail, newspaper advertisements, and community outreach—used in nonpharmacologic trials | Retrospective evaluation of recruitment approaches | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 237 dyads | African Americans | “White” and “non-white” reported | No |

|

| Romero et al., 2014 [35] | To recruit ethnically diverse, high-risk individuals for ADRD-prevention research | Community engagement approach to create a registry | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 2311 | Minorities (study did not specify specific population) | Yes | No |

|

| Samus et al., 2015 [36] | To evaluate the effectiveness of five recruitment approaches—community liaison, letters, brochures/flyers, registries, and community outreach activities—used during recruitment for an 18-month RCT on dementia care coordination | Descriptive analysis of recruitment methods for an RCT | Urban community | 303 | Minorities (study did not specify specific population) | Yes | No |

|

| Williams et al., 2011 [37] | To increase enrollment of African Americans in local ADRC studies | Community outreach using social marketing model | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 48 study enrollees and 3451 event attendees 2006-2007 | African Americans | No | No |

|

| Carr, 2010 [20] | To evaluate the effectiveness of recruitment efforts with a community grass-roots outreach event | Direct comparison of recruitment approaches | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 283 (33 providers and 250 community members) | Engaged service providers in underserved, disadvantaged areas | Age and gender reported | No |

|

| Interview-based studies on willingness, views, and/or attitudes around Alzheimer's disease research | ||||||||

| Boise et al., 2017 [38] | To explore beliefs/attitudes about brain donation among African-American, Chinese, Caucasian, and Latino research subjects and their families in focus groups | Focus group interview study; descriptive analysis | Recruitment through registry; population density not reported | 95 | Racial and ethnic minorities | Yes | Yes, longitudinal studies and clinical trials from ADCs | N/A |

| Lambe et al., 2011 [39] | To assess African-American older adult's knowledge & perceptions of brain donation | Focus group interviews, consensual qualitative research strategies | Recruitment through registry; population density not reported | 15 | African Americans | Yes | Yes, ADC research registry | N/A |

| Littlechild et al., 2015 [40] | To offer a critical account of the impact of a participatory approach at different stages of a research project | Interviews; thematic analysis | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 75 | Black and “minority ethnic community” | No | No | N/A |

| Gelman, 2010 [41] | To describe the barriers to research participation for Latino family ADRD caregivers | Qualitative field observations | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 29 | Hispanic and Latinx groups | Yes | No | N/A |

| Williams et al., 2010 [42] | To examine barriers and facilitators to ADRD research and specifically ADRD biomarker research participation among African Americans | Qualitative using focus groups | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 70 | African Americans | Yes | Partial recruitment through ADC | N/A |

| Schnieders et al., 2013 [43] | To identify barriers and incentives to engaging in ADRD research and brain donation for African Americans | Face-to-face interviews | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 91 | African Americans | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Survey-based studies on willingness, views, and/or attitudes around Alzheimer's disease research | ||||||||

| Boise et al., 2017 [44] | To identify predictors of willingness to assent to brain donation for research volunteers from four racial groups | Cross-sectional | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 479 | Racial groups (study did not specify further) | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Danner et al., 2011 [45] | To determine African-American interest in ADRD research participation | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 46 | African Americans | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Hooper et al., 2013 [46] | To explore willingness to undergo revealing genetic testing for experimental interventions | Questionnaire assessing attitudes and willingness to participate in one of four hypothetical research studies | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 34 | Hispanic or Latinx groups; people at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Howell et al., 2016 [47] | To assess relationship between prelumbar puncture perception and the lumbar puncture experience and how perception varied by race | Cross-sectional: observational and survey-based | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 128 | African Americans | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Jefferson et al., 2011 [48] | To discover incentives and barriers to participating in ADRD research studies | Surveys | Recruitment through registry; population density not reported | 235 | Minorities (study did not specify further) | Yes | Yes, ADRC research registry | N/A |

| Jefferson et al., 2011 [49] | To compare how knowledge about brain donation procedures and willingness to participate in brain-donation research vary by race | Mail survey/questionnaire | Recruitment through registry; population density not reported | 464 | African Americans | Yes | Yes, ADC research registry | N/A |

| Jefferson et al., 2013 [50] | To assess changes in attitudes toward medical research before and after participation in the group discussion. | Pre-post study design | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 52 | African Americans | Yes | Yes, ADC research registry | N/A |

| Neugroschl et al., 2016 [51] | To examine how characteristics such as age and education relate to research attitudes among urban minority elders | Survey | Urban community | 123 | African Americans and Hispanic or Latinx groups | Yes | No | N/A |

| Zhou et al., 2017 [52] | To compare willingness to participate in hypothetical preclinical trials between whites and African Americans | Post hoc secondary analysis of interview | Community-dwelling; population density not reported | 125 | African Americans | Yes | Yes | N/A |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; ADRD, Alzheimer's disease and related dementias; ADC, Alzheimer's Disease Center; ADRC, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center.

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

Of the 22 included studies, 15 focused on participant views, attitudes, and willingness to participate in ADRD research and related procedures. Six of the remaining studies reported on recruitment strategies, with one of the six describing use of a retention strategy but none evaluating retention strategies. One study examined both participant views and recruitment strategies. Overall, 18 of the 22 studies reported recruiting participants primarily from community settings, and 12 of 22 reported recruitment through an existing cohort (e.g., an Alzheimer's Disease Center research registry).

Study inclusion criteria most often included participant age (65 years and older), membership in a racial/ethnic minority group (as compared to another dimension of disadvantage), status as a dementia caregiver, and in one study, presence of dementia or mild cognitive impairment diagnosis [36]. Common study exclusion criteria included having dementia [[35], [38], [39], [44], [46], [52]], major or complicated illness [34,45], or auditory or visual impairments [52].

Enrollment and representation of specific targeted populations varied across studies, with some having 100% racial/ethnic minority enrollment and some predominantly sampling racial/ethnic minority groups but also enrolling nonminorities:

-

•

Ten studies focused on reaching African-American participants [35,37,39,42,43,45,47,49,50,52], two on Hispanic/Latinx populations [41,46], two Chinese-American populations [32,33], and one on a nonspecified South-Asian community [40].

-

•

Two studies focused on recruiting African-American, Chinese, Hispanic/Latinx, and white population in their studies [38,44].

-

•

One study specified targeting a racially diverse population, achieving a 29% non-white sample [34].

-

•

Four of 22 studies reported participant income [36,42,44,46], and two studies focused specifically on engaging people from “poor” backgrounds [51] or within “disadvantaged or underserved” areas [20].

-

•

No studies focused on or included Native American/Alaskan Native or Pacific Islander populations.

Four of 22 studies described the use of a theory or conceptual framework which included outreach [36], marketing [37], relational [20], and organizational frameworks [41]. The remaining 18 studies did not explicitly specify the use of a theoretical framework to inform a design of recruitment/retention approaches, explain the effectiveness of these approaches, or predict participation.

3.3. Measurement

Sixteen of the 22 studies used at least one structured measurement tool for data collection and/or outcome measurement. The remaining six were solely interview-based, and data consisted of qualitative evaluations [[38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]]. Most measurement tools consisted of structured questions and items that focused on concepts such as likelihood to enroll in research, attitudes toward ADRD research, potential barriers and facilitators to participating including participant religiosity/spirituality, beliefs about the body, trust in the health-care system, literacy, knowledge regarding ADRD, perceived ADRD risk, and cognitive abilities.

Across the 16 studies that used a measurement tool, seven [35,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51]] used previously tested and validated tools, which included the Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale [52], the Healthcare System Distrust Scale [49], and the AD Center Patient Lumbar Puncture Experience Survey [47]. Four of these seven studies using validated tools also used nonvalidated investigator-designed measurement tools or items [[48], [49], [50],52], and the remaining nine studies used only nonvalidated investigator-designed measurement tools or reported outcomes of a recruitment study [20,[32], [33], [34],36,37,[44], [45], [46]] (Supplementary Appendix D).

3.4. Studies reporting recruitment and retention approaches

Seven studies described recruitment and/or retention approaches. We classified recruitment approaches as (1) unsolicited communications/advertisement, (2) community-oriented events and outreach, (3) recruitment in academic or clinic settings from an existing registry of participants who had previously consented to contact for future research opportunities, and (4) use of “other sources” wherein the recruitment source and activities were not specified. Activities undertaken across these approaches varied considerably and are detailed in Table 2 along with the evaluation methods used and reported outcomes. All seven described recruitment activities and one of the seven studies discussed approaches specific to retention. Studies did not consistently specify whether specific activities related to recruitment or retention efforts.

Table 2.

Synthesis of reported recruitment approaches, activities, outcomes, and strategies

| Approach | Specific activities | Evaluation | Reported outcomes | Duration of activities | Modes of delivery and related strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsolicited communications/advertisements | Brochures, flyers, and/or information sheets | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

|

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Postal mailing | Number of interested participants; number eligible; number of non-white participants; cost |

|

|

||

| Response rate; percent yield of enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Newspaper advertisements | Number of interested participants; number eligible; number of non-white participants; cost |

|

|

||

| Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

|||

| Number of exposures, interested participants, enrollees, staff hours, total cost |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Website | Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

||

| Community-oriented events and outreach | Combination efforts | Number of interested participants; number eligible, number of non-white participants; cost |

|

|

|

| Percent yield of enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Percentage of African Americans participating in specific research activities |

|

|

|||

| Lectures, talks, educational programs on dementia, AD, and/or cognitive aging (a subset involved religiously affiliated organizations) | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|||

| Attendance |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

|||

| Number of exposures, interested participants, enrollees; staff hours, total cost |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Community/public health fairs | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

||

| Attendance |

|

|

|||

| Attendance, mailing list sign-ups, subsequent enrollments |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Community liaison engagement model | Percent yield of enrollees |

|

|

||

| Volunteer organizations | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

||

| Word-of-mouth | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

||

| Percentage of study enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Other | Attendance |

|

|

||

| Recruitment in academic or clinic settings | ADRC-related activities | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

||

| Engagement of clinical providers around ADRD education and recruitment | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

||

| Attendance at educational events |

|

|

|||

| Attendance at educational events; attitudes around recruitment; subsequent enrollment |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

|||

| “Other sources” | Recruitment sources and activities not specified | Percent yield of total registry participants |

|

|

|

| Percent yield of total ADRC enrollees |

|

|

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PIB PET, Pittsburgh compound B positron emission tomography; ADRC, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center.

Studies reported adopting various implementation and delivery strategies across recruitment activities, including employing researchers with congruent racial/ethnic identities and/or language abilities [32,35], engaging in outreach at community centers (primarily through giving lectures and presentations) [20,[32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]], and contacting participants by mail, email, and phone [36].

All studies incorporated at least one community-based approach which ranged from distributing flyers to having former participants refer people via word-of mouth and engaging with community liaison, faith-based organizations, senior centers, and support groups [20,33,37,41]. Descriptions of what constituted a community-based approach, the types, amount and distribution of engagement with various entities, and other approaches used varied considerably. For example, one study described using a “community-engagement approach” consisting of presentations at local health fairs, conferences, and churches; recruitment through active Alzheimer's Disease Research Center studies; use of media and websites; recruitment at health centers; and recruitment via “word of mouth” [35]. Other approaches included recruitment through varying intensities of community lectures, newspaper announcements, “word of mouth,” training with clinical recruitment partners, health fairs, radio and faith-based advertisements, and presentations on ADRD [20,[32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]]. Only one of these seven studies described use of a strategy to bolster both recruitment and retention, specifically through the establishment of community advisory boards to inform their work [37].

3.5. General evaluation of recruitment approaches

Just one of the seven studies described retention activities, and these activities were not systematically evaluated. Across recruitment-focused studies, evaluation methods for recruitment activities varied, including methods for measuring participant exposure to recruitment activities and the outcomes of interest. The predominant method of evaluating the effectiveness of recruitment activities was to track new enrollments by evaluating total number of new participants [20,35], number of new participants from a racial/ethnic minority group [33,37], or both [[34], [35], [36]]. Only one study evaluated more proximal endpoints by capturing total number of new referrals and exposure to recruitment activities (i.e., participants attending workshops) [32].

The duration of recruitment activities varied considerably ranging from four months [20] to three years and nine months [37]. All studies had unequal distributions in the intensity of and exposure to various recruitment activities; for example, one compared over 2000 mailings to 23 newspaper advertisements [34]. No study reported attempts to measure or document fidelity of recruitment activities (i.e., ensuring sessions are delivered similarly across sessions or settings). In all but one study, conclusions were reported without reference to variations in intensity or exposure to specific recruitment events or activities [20].

Among the seven studies evaluating recruitment approaches, only one study clearly delineated a prospective recruitment intervention [20], with the remaining studies reporting an evaluation of closely tracked recruitment methods that were part of a larger outreach project or study. Across studies, five clearly delineated a research question or objective [20,32,34,36,37] and two provided a hypothesis [20,37]. The two providing a hypothesis had specified a goal of identifying which recruitment methods would be most effective [20,37].

Most authors reported improved representation or growth in research cohorts after their recruitment efforts, with some citing success in recruiting a more diverse research cohorts [35,37] and others concluding that the use of newspaper announcements (38,000 made) yielded a slightly higher number of referrals but community lectures (249 delivered) yielded a higher number of enrollees [33]. Some authors did not draw clear conclusions on the success of recruitment according to venue or activity but highlighted the importance of certain components such as offering clinical services [32]. Two studies reported mailings yielded referrals but that in-person community activities such as community lectures or “partnership with community liaisons” yielded higher percentage of enrollees, particularly among minority groups [35,36], and one finding that mailings, when compared with outreach at community health fairs, yielded more referrals and enrollees [34].

3.6. Participant views of ADRD research

Our review identified 16 studies that examined underrepresented participant perspectives regarding ADRD research. Of these studies, 7 focused on participant views around incentives and barriers to joining an ADRD study or registry [32,[40], [41], [42],48,51,52], and the remaining 9 studies focused on specific related research procedures including brain donation [38,39,[43], [44], [45],49,50], genetic testing [46], and lumbar puncture [47]. Methodological approach was heterogeneous across these studies, with 7 studies using surveys or questionnaires, 6 using focus groups or interviews, and 3 using a combination of surveys and interviews. Study questions focused on aspects of religion/spirituality, education, motivation to participate (e.g., altruism), and trust/mistrust in health-care systems that were hypothesized to influence views surrounding participation, particularly in specific research procedures. Synthesized findings from these studies are detailed in Table 3, and they demonstrate that

-

•

Major barriers to research participation identified included fear of injury or complications, mistrust of research or medical staff, or receiving insufficient information about study, procedures, or the research process [32,[38], [39], [40],[42], [43], [44], [45],47,49].

-

•

In one study of four ethnic groups, African Americans, in particular, expressed a concern regarding the history of racism in research [38].

-

•

Major facilitators of research participation include the building of trust and rapport, race- and ethnicity-concordant researchers, and visit locations and timing that were convenient for participants [41,45,51].

-

•

Several studies concluded that education regarding ADRD itself, and the importance of ADRD research, may be valuable as a means of increasing minority recruitment [32,41,43].

Table 3.

Study-reported themes on research participation

| Study target population | General themes on research participation | Facilitators to research participation | Barriers to research participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Findings reported across one or more study populations (African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, Caucasian) |

|

Participant characteristicsResearch study characteristics | Participant characteristicsResearch study characteristics |

| Findings that are specific to one population (African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian) |

|

Participant characteristicsResearch study characteristics | Participant characteristics

|

A majority of the 16 studies used guided interviews based on predetermined sets of questions around major constructs such as education, mistrust, religion, and spiritual beliefs. In those cases, subsequent investigator-identified domains and concepts were necessarily constrained by the prespecified conceptualization (Table 3).

3.7. Quality appraisal

The five solely qualitative studies were rated by the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Qualitative Research. Three met all 10 quality criteria, one met four criteria, and the last met three criteria (Supplementary Appendix E). All studies were deemed to represent participant voices, present conclusions based on aforementioned data and analysis, and show evidence of ethical approval.

Seventeen studies were evaluated by the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, and this included studies examining recruitment approaches and studies examining views and attitudes via surveys. All were given a global rating of “weak.” Nearly all studies demonstrated high risk of bias because of a combination of selection bias (n = 8), poor study design (n = 15), confounders (n = 14), data collection (n = 12), and attrition bias (n = 12) (Supplementary Appendix F).

4. Discussion

We found that despite important efforts and contributions toward enhancing the representativeness of ADRD research cohorts, the overall strength of evidence regarding effective strategies for bolstering recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in ADRD research is both low and limited to specific populations and predominantly large research institutions or Alzheimer's Disease Centers. We found considerable heterogeneity in recruitment approaches and strategies and in measurement of the delivery of these approaches and their outcomes. Ultimately, owing to the limited scope of evidence, methodological limitations in study design, and variability in measurement and evaluation across studies, the existing literature cannot be readily used by other investigators or sites to adapt or implement an effective approach to improve recruitment or retention efforts within their own ADRD research programs. While investigators generally reported that their recruitment efforts were successful, metrics for quantifying effectiveness at this emergent stage are inconsistent, and in some cases, they lack adequate empiric support because of the retrospective nature of much of the current evidence. Findings from studies investigating participant perspectives highlight shared motivators (i.e., altruism) and barriers (i.e., mistrust, financial, or geographic accessibility) to ADRD research participation. However, areas of inquiry in data collection in these studies were largely driven by investigators' predetermined explanations of participation, which may have constrained study findings.

Although a few groups have long focused on the science surrounding research access, inclusion, and participation [[53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58]], we found that recruitment science, as applied to ADRD research engagement, reflects a field in early stages of development, with many creative approaches being adopted to broaden inclusivity. While the present article presents a systematic review of existing evidence, it is possible that additional relevant reports would have been identified through inclusion of more databases, and because of inconsistent reporting surrounding ethnicity, it is unclear how well included studies characterized heterogeneous racial/ethnic populations. Yet, findings from this review clarify the scope of existing empiric evidence and, in particular, illustrate limitations inherent in attempts to draw conclusions based on retrospective evaluation of recruitment activities, which highlights how an applied recruitment science for ADRD research will benefit from incorporation of rigorous prospective designs, standardized measurement, and evaluative approaches.

4.1. Design and measurement considerations for future research

This review also identifies common design-based limitations that reduced confidence in study findings and limited our ability to identify common patterns and features of effective approach. Essentially all studies included in this review were subject to considerable sampling bias in that the represented samples are unlikely to provide results that can be generalized to a larger population. Furthermore, more than half used nonvalidated or nonstandardized instrumentation, thereby increasing the possibility of measurement error. While the use of standard instrumentation not validated within an underrepresented population can also result in measurement error, its absence hinders the reproducibility of the studies in question. These limitations suggest a need to develop sampling and measurement quality metrics specific to recruitment science to evaluate the nuances and complexities of answering questions related to research recruitment, retention, and participation.

Measurement-related weaknesses were not limited to instrumentation as this review also identifies variation in measurement of recruitment activity exposure and outcomes. Most studies included reports of multifaceted and multipronged efforts to enhance outreach, recruitment of specific populations, and nearly all reported improvements in their overall recruitment numbers as a result of their efforts. However, these studies often failed to measure exposure to recruitment activities and did not distinguish recruitment outcomes based on the type or the quantity of specific recruitment strategies to which participants were exposed. Furthermore, our review found that many studies report imbalanced use of recruitment approaches, for instance, mailing thousands of letters and additionally offering a few community presentations, and only one study reported considering the imbalances in these techniques in the conclusions that are drawn regarding effectiveness.

While many retrospective studies reported successful recruitment efforts for underrepresented populations [[34], [35], [36]], it is important to recognize that retrospective reports lack the features of systematic inquiry and scientific process that would allow other teams to evaluate and replicate those successes and achieve the progress required. While these data clearly provide strong anecdotal support for the feasibility of launching successful efforts to improve inclusion of individuals from underrepresented backgrounds in ADRD research, what they do not provide is strong empiric support to direct future recruitment and retention resources, inform targeted activities and procedures, and evaluate progress.

4.2. Dissemination and reporting considerations for future research

There are other omissions in the dissemination process that could be amended to promote progress. Synthesized findings from reports of recruitment and retention approaches highlight common strategies: (1) including a diverse study team with a relationship to target communities [32,33,35,36]; (2) establishing a multiplicity of messaging channels and recruitment venues including community organizations, clinics, and faith-based organizations through passive or active engagement (e.g., participation in adult day/senior centers) [20,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37]]; and, in some cases, (3) developing explicit structures of accountability within study teams which heighten awareness surrounding issues related to trust and relationships such as the ongoing use of a community advisory board [36,37,59]. What is lacking in many reports is a more comprehensive understanding and/or description of the local and community contexts within which these efforts took place. A strong sense of the context in which a given activity was successful, and the rationale for selecting that activity, is central to understanding other situations and contexts within which similar priorities and approaches may be merited.

For example, some scholars have identified racial concordance, termed “symbolic diversity,” insufficient to facilitate adequate recruitment, absent other approaches to establish trust and connection [60,61]. In many instances, these efforts appear to involve not only building teams that are representative of diverse participants but also individuals that represent individual communities [32,33,36,37] and are supported in translating community preferences and values into recruitment plans and activities [36,37]. Absent this understanding, scientists may be led to believe that simply adding a racial/ethnic minority is sufficient to achieve improved inclusion. Similarly, assumptions that members of the same racial or ethnic group hold homogenous preferences regarding research participation or experience the same barriers and facilitators for participation may exacerbate unintended consequences of “symbolic diversity” as ethnic and cultural identities are often multifaceted and heterogeneous. More precise and contextualized description of concepts such as racial concordance can help in clarifying this practice and its value.

Another barrier to the adoption of effective recruitment practices is the lack of sufficiently detailed procedures that operationalize how these concepts are translated into actions and behaviors by study teams. No studies reviewed provided standardized documentation that could be used to guide replication of these activities in their published reports. Examples of such materials might include engagement manuals, detailed descriptions of the delivery and exposure of recruitment interventions/strategies, specification of sequential procedures, resource requirements, and attempts to characterize or evaluate fidelity to established principles or procedures. Absent more sophisticated delineation of recruitment interventions or activities, the multifarious efforts of scientists endeavoring to bolster inclusivity of ADRD research run the risk of stagnating rather than progressing and collectively building an empirically informed evidence base from which to inform best practices in recruitment and retention. To some extent, this is reflective of the unfortunate reality that oftentimes recruitment and retention efforts are a supplement or add-on to achieving scientific output rather than a central part of the research process. While resource and time scarcity undoubtedly contribute to challenges in undertaking more complete documentation of recruitment activities, the lack of an accessible, sufficiently detailed foundation of evidence is a notable limitation to supporting ADRD researchers in improving their own recruitment efforts.

4.3. Opportunities for use of theoretical frameworks to guide recruitment science

Many of the design- and dissemination-based limitations described previously reflect a lack of evidence-based recruitment models observed in the reviewed literature. Only four of the 22 studies explicitly used a conceptual framework/recruitment model to inform their study design or execution. Overwhelmingly, studies investigating the views of individuals from underrepresented backgrounds regarding ADRD research participation relied on explanations related to participant's attitudes, willingness, religiosity, education, and trust. Because most studies had preselected these domains to inform their data collection, findings did largely reflect participant comments and views supporting this theoretical position. Considerable evidence from other research contexts suggests that trust is of central relevance to understanding research participation among some populations, specifically African-American and American-Indian populations [[62], [63], [64]]. However, the assumption that individual-level mistrust, or even participant attitudes toward research more generally, is the largest barrier to participation in ADRD research is not necessarily empirically supported.

Provided the small number of articles explicitly describing the use of a theoretical framework, there is insufficient evidence from the available literature to endorse a specific theoretical perspective for improving recruitment of underrepresented populations in ADRD research. Experts have proposed that more diverse theoretical perspectives are needed to disentangle complex motivators, barriers, and decision-making processes regarding research enrollment and attrition. In addition to advocating for broader understanding of societal experiences of discrimination and trust, some researchers have proposed that, as a form of health behavior, research participation can be investigated through the lens of well-developed theories such as the health belief model [[65], [66], [67]]. In addition, community-based participatory research frameworks, wherein community involvement extends beyond the research subject participant level and take an active role in shaping research questions and process, have been identified as a powerful tool in expanding inclusivity in research particularly among underrepresented populations [22,23]. Findings from this review suggest that continued reliance on a unidimensional perspective of research participation relating to primarily nonmodifiable demographic/identity characteristics or attitude and willingness is likely inadequate to inform sufficiently robust investigation into ADRD and population-specific research participation frameworks. As these recruitment efforts continue to improve and the field begins to advance, it is also imperative to consider who is still missing from the partnerships and engage with communities—and individuals—which remain nearly absent from the reviewed reports and often from the discussion at large.

4.4. Who is excluded?

We also found that despite substantial inclusivity efforts, there remain significant omissions in population, perspective, and settings represented. First, our review found that several populations were minimally represented or entirely absent from this literature, including the American Indians/Alaskan Natives and Pacific Islanders, who, according to reported sample characteristics, were not included in any of the available studies. We also found that few studies focused specifically on persons from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and inclusion of socioeconomically disadvantaged populations in included studies was low. We also found that despite substantial inclusivity efforts, there remain significant omissions in population, perspective, and setting. It is worth noting that 27% (6 out of 22) of studies excluded individuals with dementia. It is concerning that the intended beneficiaries of ADRD research are so often systematically excluded from studies that relate directly to them [68]. There are undoubtedly many challenges to including people with symptomatic ADRD in research; however, through adaptations and additional protections, it is often feasible to interview and collect data from people with mild to moderate ADRD [[69], [70], [71]]. The importance of increasing representation of the perspectives of people with ADRD in research has been highlighted as a priority by the National Institute on Aging National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers and by advocacy organizations [72].

Finally, the vast majority of studies focused recruitment efforts on primary care settings and community settings. No study facilitated recruitment through settings providing acute illness care, such as urgent care or emergency department settings, despite evidence that many underrepresented populations disproportionately rely on acute illness care to meet basic and primary care needs and are less likely to have and use primary care [[73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78]]. While these settings present challenges for recruitment, extensive work from emergency medicine, cancer, and palliative care research demonstrate that recruitment surrounding acute illness care is feasible and, as a result, may represent a missed opportunity for ADRD research recruitment efforts [74,[79], [80], [81]].

A final concern related to inclusivity, and generalizability of findings concerns the preponderance of evidence coming from Alzheimer's Disease Center participants. Much of the evidence reviewed is constrained to the context of established research centers and has, in most cases, been generated with research participants who have already engaged in established longitudinal cohort studies or affiliated with Alzheimer's Disease Centers. As a result, many of these studies have tended to focus on minority populations of particular relevance to the geographic regions surrounding their research centers. For several studies, participants were drawn from established cohorts, suggesting that many of these study findings reflect views of individuals who are generally more familiar with the concept of ADRD and research than the general public.

5. Conclusions

It is imperative that the ADRD field continue to expand research participation through efforts that are inclusive and that ensure accessibility for populations that are historically underincluded despite experiencing disproportionate disease impact. It is also imperative that inclusive research be scientifically valid and findings generalizable to the target population. Despite commendable efforts made by scientists to bolster inclusion of members from underrepresented groups in ADRD research, there are considerable scientific gaps that limit the use of these substantial efforts for informing future ADRD recruitment efforts in an evidence-based manner. Future efforts should generate empirically derived strategies with potential for broad dissemination. Our findings reveal that important prerequisites to these efforts will include the development of standardized design principles, including thoroughly operationalized outcomes and validated instrumentation that can be prospectively adapted for and used across institutions, settings, and populations, and will be guided by established methodological standards for recruitment science. Provided the importance of local contexts and diversity in values and norms across cultures and regions, development of locally relevant measures and standards may also be merited. And finally, while a majority of ADRD research is generated by established Alzheimer's Disease Centers and the foundation of ADRD recruitment science is likely to reflect Alzheimer's Disease Center's cohort characteristics and infrastructure, a national, interdisciplinary effort to address ADRD will require establishing the effectiveness of similar strategies for institutions and communities that are currently unconnected to Alzheimer's Disease Center resources.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The authors used traditional sources to uncover and review recent literature evaluating Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) recruitment or related topics. The current recruitment crisis in ADRD studies stifles scientific progress and ability to evaluate ADRD in underrepresented populations.

-

2.

Interpretation: The study of recruitment, retention, and participation in ADRD research is in its early stages. Our findings illustrate the current status of research on ADRD recruitment and retention and underrepresented participant views around ADRD research, revealing low quantity and quality of evidence. Our review provides an understanding of approaches used and gaps to be addressed.

-

3.

Future directions: We propose the following for future scientific inquiry: development of methodological standards for recruitment science; standardized assessment and quality metrics for evaluation of ADRD research participation; prospective examination of recruitment and retention approaches with rigorously reported procedures; and improved conceptualization of concepts related to recruitment, retention, participation, and inclusion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Senior Academic Librarian Mary E. Hitchcock, MA, MLS, for support with database search methodology and Jennifer Morgan and Clark Benson for assistance with study review and manuscript formatting.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number (K76AG060005 [A.L.G.-B.] and K24AG05560 [M.N.S.]), as well as the African Americans Fighting Alzheimer's in Midlife grant (R01 AG054059 [C.G.]) and the Alzheimer's Association (AARF-18-562958 [M.Z.]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.National Plan to Address Alzheimer's Disease. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington D.C., Maryland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olin J.T., Dagerman K.S., Fox L.S., Bowers B., Schneider L.S. Increasing ethnic minority participation in Alzheimer disease research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:S82–S85. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes L.L., Bennett D.A. Alzheimer's disease in African Americans: risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:580–586. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green R.C., Cupples L.A., Go R., Benke K.S., Edeki T., Griffith P.A. Risk of dementia among White and African American relatives of patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayeda E.R., Glymour M.M., Quesenberry C.P., Whitmer R.A. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick A.L., Kuller L.H., Ives D.G., Lopez O.L., Jagust W., Breitner J.C.S. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graff-Radford N.R., Besser L.M., Crook J.E., Kukull W.A., Dickson D.W. Neuropathologic differences by race from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faison W.E., Schultz S.K., Aerssens J., Alvidrez J., Anand R., Farrer L.A. Potential ethnic modifiers in the assessment and treatment of Alzheimer's disease: challenges for the future. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:539–558. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700511X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frozza R.L., Lourenco M.V., De Felice F.G. Challenges for Alzheimer's disease therapy: insights from novel mechanisms beyond memory defects. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:37. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes L.L. Biomarkers for Alzheimer dementia in diverse racial and ethnic minorities—A public health priority biomarkers in diverse racial and ethnic minorities editorial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:251–253. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wight R.G., Aneshensel C.S., Miller-Martinez D., Botticello A.L., Cummings J.R., Karlamangla A.S. Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaffe K., Falvey C., Harris T.B., Newman A., Satterfield S., Koster A. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: prospective study. BMJ. 2013;347:f7051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang I.A., Llewellyn D.J., Langa K.M., Wallace R.B., Huppert F.A., Melzer D. Neighborhood deprivation, individual socioeconomic status, and cognitive function in older people: analyses from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeki Al Hazzouri A., Haan M.N., Osypuk T., Abdou C., Hinton L., Aiello A.E. Neighborhood socioeconomic context and cognitive decline among older Mexican Americans: results from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:423–431. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fargo K.N., Carrillo M.C., Weiner M.W., Potter W.Z., Khachaturian Z. The crisis in recruitment for clinical trials in Alzheimer's and dementia: an action plan for solutions. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1113–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy R.E., Cutter G.R., Wang G., Schneider L.S. Challenging assumptions about African American participation in Alzheimer disease trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25:1150–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Painter J.E., Borba C.P.C., Hynes M., Mays D., Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:358–362. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishbein M., Yzer M.C. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theor. 2003;13:164–183. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winter S.J., Sheats J.L., King A.C. The use of behavior change techniques and theory in technologies for cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment in adults: a comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr S.A., Davis R., Spencer D., Smart M., Hudson J., Freeman S. Comparison of recruitment efforts targeted at primary care physicians versus the community at large for participation in Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:165–170. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181aba927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frerichs L., Lich K.H., Dave G., Corbie-Smith G. Integrating systems science and community-based participatory research to achieve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:215–222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallerstein N., Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De las Nueces D., Hacker K., DiGirolamo A., Hicks L.S. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:1363–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Together We Make the Difference: National Strategy for Recruitment and Participation in Alzheimer's and Related Dementias Clinical Research. National Institute on Aging; Bethesda, Maryland: 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochrane Collaborative. https://www.cochrane.org/ Accessed February 13, 2019.

- 26.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George S., Duran N., Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; 2019.

- 29.Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C.R., Hagen N.A., Biondo P.D., Cummings G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute J.B. Joanna Briggs Institute in Adelaide; Australia: 2017. Checklist for Qualitative Research; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chao S.Z., Lai N.B., Tse M.M., Ho R.J., Kong J.P., Matthews B.R. Recruitment of Chinese American elders into dementia research: the UCSF ADRC experience. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S125–S133. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li C., Neugroschl J., Umpierre M., Martin J., Huang Q., Zeng X. Recruiting US Chinese elders into clinical research for dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30:345–347. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison K., Winter L., Gitlin L.N. Recruiting community-based dementia patients and caregivers in a nonpharmacologic randomized trial: what works and how much does It cost? J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35:788–800. doi: 10.1177/0733464814532012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero H.R., Welsh-Bohmer K.A., Gwyther L.P., Edmonds H.L., Plassman B.L., Germain C.M. Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer disease prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:269–274. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samus Q.M., Amjad H., Johnston D., Black B.S., Bartels S.J., Lyketsos C.G. Adaptive approach for the recruitment of diverse community-residing elders with memory impairment: the MIND at home experience. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams M.M., Meisel M.M., Williams J., Morris J.C. An interdisciplinary outreach model of African American recruitment for Alzheimer's disease research. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S134–S141. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boise L., Hinton L., Rosen H.J., Ruhl M. Will my soul go to heaven if they take my brain? Beliefs and worries about brain donation among four Ethnic Groups. Gerontologist. 2017;57:719–734. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambe S., Cantwell N., Islam F., Horvath K., Jefferson A.L. Perceptions, knowledge, incentives, and barriers of brain donation among African American elders enrolled in an Alzheimer's research program. Gerontologist. 2011;51:28–38. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Littlechild R., Tanner D., Hall K. Co-research with older people: Perspectives on impact. Qual Social Work. 2015;14:18–35. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelman C.R. Learning from recruitment challenges: barriers to diagnosis, treatment, and research participation for Latinos with symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontological Soc Work. 2010;53:94–113. doi: 10.1080/01634370903361847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams M.M., Scharff D.P., Mathews K.J., Hoffsuemmer J.S., Jackson P., Morris J.C. Barriers and facilitators of African American participation in Alzheimer disease biomarker research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:S24–S29. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f14a14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnieders T., Danner D.D., McGuire C., Reynolds F., Abner E. Incentives and barriers to research participation and brain donation among African Americans. Am J Alzheimer's Dis other Demen. 2013;28:485–490. doi: 10.1177/1533317513488922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boise L., Hinton L., Rosen H.J., Ruhl M.C., Dodge H., Mattek N. Willingness to be a brain donor: a survey of research volunteers from 4 racial/ethnic groups. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:135–140. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darnell K.R., McGuire C., Danner D.D. African American participation in Alzheimer's disease research that includes brain donation. Am J Alzheimer's Dis other Demen. 2011;26:469–476. doi: 10.1177/1533317511423020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hooper M., Grill J.D., Rodriguez-Agudelo Y., Medina L.D., Fox M., Alvarez-Retuerto A.I. The impact of the availability of prevention studies on the desire to undergo predictive testing in persons at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Howell J.C., Parker M.W., Watts K.D., Kollhoff A., Tsvetkova D.Z., Hu W.T. Research lumbar punctures among African Americans and Caucasians: perception predicts experience. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:296. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jefferson A.L., Lambe S., Chaisson C., Palmisano J., Horvath K.J., Karlawish J. Clinical research participation among aging adults enrolled in an Alzheimer's Disease Center research registry. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2011;23:443–452. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jefferson A.L., Lambe S., Cook E., Pimontel M., Palmisano J., Chaisson C. Factors associated with African American and White elders' participation in a brain donation program. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25:11–16. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f3e059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jefferson A.L., Lambe S., Romano R.R., Liu D., Islam F., Kowall N. An intervention to enhance Alzheimer's disease clinical research participation among older African Americans. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2013;36:597–606. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neugroschl J., Sewell M., De La Fuente A., Umpierre M., Luo X., Sano M. Attitudes and perceptions of research in aging and dementia in an Urban Minority Population. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;53:69–72. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Y., Elashoff D., Kremen S., Teng E., Karlawish J., Grill J.D. African Americans are less likely to enroll in preclinical Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimer's Dement (N Y) 2017;3:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dilworth-Anderson P., Cohen M.D. Beyond diversity to inclusion: recruitment and retention of diverse groups in Alzheimer research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:S14–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Passmore S.R., Fryer C.S., Butler J., 3rd, Garza M.A., Thomas S.B., Quinn S.C. Building a “Deep Fund of Good Will”: reframing research engagement. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:722–740. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quinn S.C., Butler J., 3rd, Fryer C.S., Garza M.A., Kim K.H., Ryan C. Attributes of researchers and their strategies to recruit minority populations: results of a national survey. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin-Wells V., McDougall G.J., Becker H. Recruiting and retaining and ethnically diverse sample of older adults in a longitudinal intervention study. Educ Gerontol. 2006;31:159–170. doi: 10.1080/03601270500388190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ballard E.L., Gwyther L.P., Edmonds H.L. Challenges and opportunities: recruitment and retention of African Americans for Alzheimer's disease research: lessons learned. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:S19–S23. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDougall G.J., Simpson G., Friend M.L. Strategies for research recruitment and retention of older racial and ethnic minorities. J Gerontological Nurs. 2015;41:14–23. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20150325-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yancey A.K., Ortega A.N., Kumanyika S.K. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dilworth-Anderson P. Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fryer C.S., Passmore S.R., Maietta R.C., Petruzzelli J., Casper E., Brown N.A. The symbolic value and limitations of racial concordance in minority research engagement. Qual Health Res. 2016;26:830–841. doi: 10.1177/1049732315575708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennedy B.R., Mathis C.C., Woods A.K. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers. 2007;14:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smirnoff M., Wilets I., Ragin D.F., Adams R., Holohan J., Rhodes R. A paradigm for understanding trust and mistrust in medical research: the Community VOICES study. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018;9:39–47. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2018.1432718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scharff D.P., Mathews K.J., Jackson P., Hoffsuemmer J., Martin E., Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rollins L., Sy A., Crowell N., Rivers D., Miller A., Cooper P. Learning and action in community health: using the health belief model to assess and educate African American community residents about participation in clinical research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garza M.A., Quinn S.C., Li Y., Assini-Meytin L., Casper E.T., Fryer C.S. The influence of race and ethnicity on becoming a human subject: factors associated with participation in research. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;7:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lincoln K.D., Chow T., Gaines B.F., Fitzgerald T. Fundamental causes of barriers to participation in Alzheimer's clinical research among African Americans. Ethn Health. 2018:1–15. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1539222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor J.S., DeMers S.M., Vig E.K., Borson S. The disappearing subject: exclusion of people with cognitive impairment and dementia from geriatrics research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:413–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mayo A.M., Wallhagen M.I. Considerations of informed consent and decision-making competence in older adults with cognitive impairment. Res gerontological Nurs. 2009;2:103–111. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090401-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holden T.R., Keller S., Kim A., Gehring M., Schmitz E., Hermann C. Procedural framework to facilitate hospital-based informed consent for dementia research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:2243–2248. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slaughter S., Cole D., Jennings E., Reimer M.A. Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14:27–40. doi: 10.1177/0969733007071355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gitlin L.N., Maslow K., Khillan R. 2018. Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer's Research, Care and Services. National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and their Caregivers. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saadi A., Himmelstein D.U., Woolhandler S., Mejia N.I. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology. 2017;88:2268–2275. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Glickman S.W., Anstrom K.J., Lin L., Chandra A., Laskowitz D.T., Woods C.W. Challenges in enrollment of minority, pediatric, and geriatric patients in emergency and acute care clinical research. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:775–780.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rust G., Ye J., Baltrus P., Daniels E., Adesunloye B., Fryer G.E. Practical barriers to timely primary care access: impact on adult use of emergency department services. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1705–1710. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Behr J.G., Diaz R. Emergency department frequent utilization for non-emergent presentments: results from a regional Urban Trauma Center Study. PloS One. 2016;11:e0147116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knowlton A., Weir B.W., Hughes B.S., Southerland R.J., Schultz C.W., Sarpatwari R. Patient demographic and health factors associated with frequent use of emergency medical services in a midsized city. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:1101–1111. doi: 10.1111/acem.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mayberry R.M., Mili F., Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:108–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sygna K., Johansen S., Ruland C.M. Recruitment challenges in clinical research including cancer patients and their caregivers. A randomized controlled trial study and lessons learned. Trials. 2015;16:428. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0948-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]