Abstract

Mapping the circuits underlying the generation and propagation of seizures is critically important for understanding their pathophysiology. We review evidence to suggest that circuits engaged in secondarily generalized seizures are likely to be more complex than those currently proposed. Focal seizures have been proposed to engage canonical thalamocortical circuits that mediate primary generalized absence seizures, leading to secondarily generalized tonic clonic seizures. In addition to traveling through the canonical thalamocortical circuits, secondarily generalized seizures could also travel through the striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra reticulata, and corpus callosum to the contralateral hemisphere. Recruitment of principal neurons in superficial layers 2/3 of the cortex can play a critical role in cortico-cortical seizure spread. Understanding the neuronal structures engaged in generating secondarily generalized seizures could provide novel targets for neuromodulation for the treatment of seizures. Furthermore, these sites may be loci of neuronal plasticity facilitating epileptogenesis.

Keywords: Secondarily generalized seizures, motor cortex, corpus callosum, striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra reticulata, thalamocortical

• Introduction

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCSs) are very dangerous because they increase the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and injuries [1]. SUDEP is a sudden, unexpected, nontraumatic and nondrowning death in patients with epilepsy, with or without evidence of seizures and excluding documented status epilepticus, in which postmortem examination does not reveal toxicologic or anatomic cause of death [2]. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures or the absence of seizure freedom are the major risk factors for SUDEP. For example, people who have three GTCSs per year have a 15-fold increased risk for SUDEP [3]. Forceful convulsions that are associated with GTCSs can also lead to falls and severe injuries [4]. To understand the pathophysiology of generalized seizures, the circuits generating and propagating the seizures must be delineated.

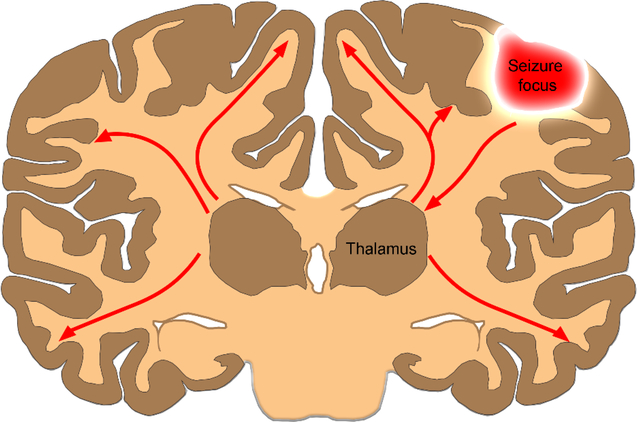

During secondary generalization of seizures, focal seizures have been proposed to spread from the cortex to the thalamus and then engage the thalamocortical circuits [5] (Fig. 1). Thalamocortical oscillations play a critical role in generating primary generalized seizures. However, unlike primarily generalized absence seizures, secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures affect the motor cortex, giving rise to convulsions. Motor cortex anatomy and the afferent and efferent connections are quite distinct from those of the somatosensory cortex, which is engaged in absence seizures. We propose that secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures not only engage the canonical thalamocortical circuit but also travel through the striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra pars reticulata, and the fibers of the corpus callosum, engaging the superficial cortical layers ahead of the deep layers.

Fig. 1.

The canonical thalamocortical circuit. Focal seizures spread from the cortex to the thalamus, engaging the thalamocortical circuit as a mechanism for secondary generalization.

• Seizure circuits

• The thalamocortical circuit underlies primarily generalized seizures

Sleep circuits mediate primary generalized absence or petit mal seizures. During natural sleep, the thalamus generates spindle oscillations of 7 to 14 Hz, which are the result of network interactions between the reticular thalamic nucleus (RTN), thalamocortical neurons, and cortical pyramidal neurons [6]. Intracellular in vivo recordings show that the burst firing of GABAergic reticular thalamic neurons induces inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) of the thalamocortical neurons, which leads to deinactivation of the low-threshold Ca2+ current (IT) and rebound bursts in thalamocortical neurons [7]. The mechanism of these natural spindle oscillations is thought to underlie the spike-and-wave discharges observed in generalized absence seizures [8]–[11]. During absence seizures, inhibitory reticular thalamic neurons drive the excitatory behavior in the ventrobasal thalamic nucleus (VB, which consists of the ventroposterior medial and lateral nuclei, VPM/VPL) and layer 4 of the somatosensory cortex, which receives projections from the VB through deinactivation of T-type Ca2+ channels. The effectiveness of GABAB antagonists to decrease seizure frequency in genetic absence epilepsy rats and drugs such as ethosuximide, T-type calcium channel blocker, in the treatment of absence seizures supports the thalamocortical mechanism of primarily generalized absence seizures [12], [13].

The circuits that underlie secondarily generalized tonic clonic seizures have not been studied in detail. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) studies in human patients during secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures as well as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)-induced generalized tonic-clonic seizures in patients with refractory depression indicate that recruitment of the thalamus supports its proposed role in seizure generalization [14], [15]. 2-Deoxyglucose (DG) metabolic mapping studies also indicate thalamic activation; however, these studies also show activation of structures outside of the thalamocortical circuit, such as the substantia nigra [16], [17].

• Secondarily generalized seizures affect the motor cortex

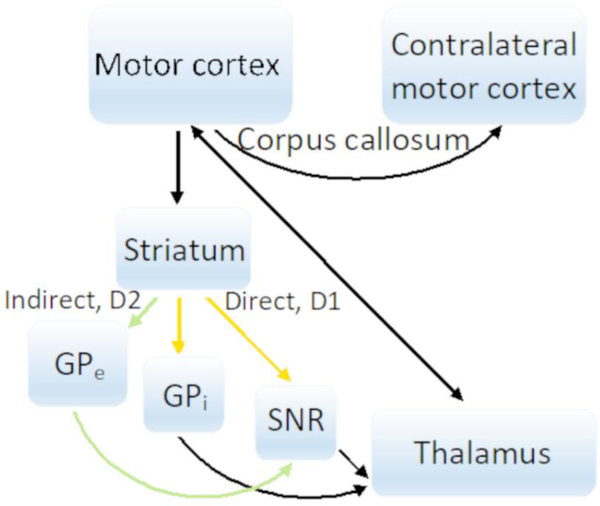

Convulsions during secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures are the result of seizures affecting the motor cortex. Hughlings Jackson first recognized that convulsions are the result of seizures affecting the contralateral motor cortex [18]. Unlike the somatosensory cortex, the motor cortex does not contain layer 4, and as seizures that affect the motor cortex and convulsions appear, there are no direct thalamic projections from the VPM/VPL to layer 4. The subcortical and intralaminar circuits that underlie those seizures are less clear. Motor thalamic nuclei such as the ventroanterior (VA), ventrolateral (VL), and ventromedial (VM) nuclei project directly to layers 2–6 of the motor cortex [19]. The motor cortex projects back to these thalamic nuclei from layers 5B and 6. The motor cortex also sends projections across the corpus callosum and to the striatum, which in turn projects to the globus pallidus and substantia nigra reticulata [20], [21] (Fig. 2). The canonical thalamocortical theory of seizure spread disregards the purpose of the corpus callosum during secondary generalization of seizures from one hemisphere to the other, and it does not explain why manipulation of the basal ganglia can affect seizures.

Fig. 2.

The proposed circuit of secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. As seizures affect the motor cortex, they spread through the fibers of the corpus callosum, striatum, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra reticulata (either via the direct or indirect circuit), as well as through the thalamocortical projections.

• Anatomy of the motor cortex and activity spread through its subcortical connections

In the motor cortex, there are three types of principal neurons that project cortico-cortically as well as subcortically [19], [22]. IT-type neurons are intratelencephalic neurons located in all cortical layers 2/3, 5A/B, and 6. These neurons project to the identical contralateral cortex across the corpus callosum, to the striatum, and cortico-cortically. PT-type neurons are the pyramidal tract neurons in layer 5B. These neurons project to the brainstem and spinal cord, sending collaterals to the striatum and thalamus. CT-type neurons are corticothalamic neurons in layer 6 and send their projections to the thalamus.

IT-type neurons of all cortical layers and the collaterals of PT-type neurons of layer 5B exit the motor cortex to enter the striatum. IT-type neurons go to both the ipsilateral and contralateral striatum, whereas PT-type neurons go to the ipsilateral striatum only. The striatum is divided into ventral and dorsal parts [23]. The ventral striatum consists of the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle, and the dorsal striatum includes the caudate and putamen. Axons from the motor cortex enter the striatum at the dorsal part, whereas those from sensory cortical areas enter at the ventral part. Almost 90% of all striatal neurons are inhibitory GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs). Two main output areas of the striatum are the globus pallidus (GP), which is subdivided into the internal (GPi) and external (GPe) segments, and the substantial nigra reticulata (SNR).

As fibers travel from the motor cortex into the striatum, they go either through the direct or indirect circuit. In the direct circuit, after passing the striatum, axons go to the GPi or to SNR, after which they enter the VA and VL nuclei in the thalamus. Medium spiny neurons in the direct path contain dopamine 1 (DRD1) receptors. In the indirect circuit, the striatum projects to the GABAergic neurons of the GPe that go to the subthalamic nucleus (STN), which sends excitatory glutamatergic projections to the SNR to enter the VA/VL nuclei in the thalamus as well. Neurons in the indirect pathway are distinguished by containing dopamine type 2 (DRD2) receptors.

It would be surprising if seizure activity traveled through the sea of inhibition of the striatal GABAergic neurons after affecting the motor cortex. However, the Turski group demonstrated that application of the dopamine agonist apomorphine in the anterior parts of the striatum protects rats from pilocarpine-induced seizures [24]. Specifically, these authors found that only D2 agonist LY-171555 protects animals from seizures, whereas the application of D1 agonist SKF-38393 in the striatum has no effect. The application of haloperidol, a D2 receptor antagonist, blocked the anticonvulsant actions of the D2 agonist and apomorphine.

Modulation of dopamine receptors in humans changes seizure susceptibility. Treatments with atypical antipsychotics, which are serotonin and dopamine-receptor antagonists, increase seizure risk [25], [26]. Groups treated with either clozapine or olanzapine, which are both dopamine, serotonin, histamine, adrenergic, and muscarinic receptor antagonists, with olanzapine having higher affinity for D2 receptors than clozapine, showed a 3.5% and 0.9% incidence of seizures, respectively, compared to placebo-treated groups during phase II-III clinical trials [27], [28].

As the motor cortex projects to the striatum, one of the major output structures of the striatum is the substantia nigra reticulata (SNR). Activation of the SNR has been found during generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 2-deoxyglucose mapping studies [16], [17], [29]. Additionally, previous decades of research have shown that stimulation of the SNR leads to suppression of seizures, and microinfusion of bicuculine (GABAA antagonist) into the SNR has a proconvulsant effect [30].

Motor cortical pyramidal neurons also send their axons across the corpus callosum, where 80% of callosal fibers come from layer 2/3, 20% from layer 5, and a small amount from layer 6 pyramidal neurons [31]. The corpus callosum is the largest commissure of the brain that connects the two hemispheres, and many studies have shown that seizures utilize it for their spread to the contralateral hemisphere [32], [33]. Oligodendroglioma lesions that are directly connected to the genu of the corpus callosum have been shown to be significantly more likely to cause generalized tonic-clonic seizures than lesions in other brain regions, whereas no correlation was observed between tumor size and generalized seizure frequency [34]. A corpus callosotomy study indicated that seizures were reduced by 50% in 79% of patients who underwent callosotomy [35], and in another study, two-thirds of patients experienced total cessation of generalized tonic-clonic seizures and drop attacks [36].

• Intralaminar seizure propagation through the motor cortex

In previous studies, slice recordings indicated that layers 4 and 5 of the somatosensory cortex play an important role in cortical seizure initiation and cortico-cortical propagation [37], [38], which makes intralaminar seizure spread within the motor cortex less clear. The canonical circuit indicates that excitation of the deep layers 4/5 drives the excitation in the superficial layers 2/3 [39]–[41]. However, as seizures affect the motor cortex, the absence of layer 4 in the motor cortex suggests that seizures likely utilize different laminar circuits.

Shepherd and colleagues proposed a top-down laminar organization of the motor cortex, where layers 2/3 drive the excitation within the deep layers [42]. In this study, glutamate uncaging by laser photostimulation of presynaptic neurons in one layer and electrophysiological recording of postsynaptic neurons in another layer were used to determine the layer-specific wiring of the motor cortex. The results indicated that the strongest excitatory pathway is from L2/3 descending to L5A/B. A weaker ascending pathway is also present from L5A to 2/3. The horizontal pathways are the strongest in L2, followed by those in L5A/B through L5B/6, and the weakest is in L3/5A and 6. These results indicate that the flow of excitation in the motor cortex is downwardly oriented from L2. Laminar epileptogenicity was also measured, which was expressed as a likelihood of an event per stimulus. Even under strongly excitable conditions with high stimulus intensities and unblocked NMDA receptors, a stimulus in L5B remains nonepileptogenic, with a local stimulus failing to spread through the network, whereas L2 demonstrates downward excitability and recurrent excitation.

Yuste and colleagues used two-photon microscopy to determine through which cortical layers seizures propagate in vivo [43]. These investigators recorded from the somatosensory cortex using 4-AP or picrotoxin application in layer 5 to evoke ictal activity. The results indicated that ictal recruitment of layer 2/3 occurs ahead of that of L5. Another finding was a vertical delay in the lateral spread of seizures with layer 2/3 recruitment occurring before the recruitment of layer 5.

• Conclusions

More evidence now suggests that the spread of secondarily generalized seizures is more complex than that of primarily generalized absence seizures. Not only does manipulation of the basal ganglia affect seizure initiation and generalization, but corpus callosotomies also decrease the frequency of secondarily generalized seizures in patients. The canonical thalamocortical model of seizure generalization alone does not explain these findings, which indicates that the spread of secondarily generalized seizures is more complex than previously thought.

Understanding the circuit that secondarily generalized seizures affect has a potential for indicating novel targets for neuromodulation. The structures targeted by secondarily generalized seizures could also be loci of neuronal plasticity, with first seizures consolidating the circuit for future seizures.

These and future studies are necessary because ignoring the complexity of the network and reducing it to simple thalamocortical oscillations provide a danger of missing novel clinical therapies for people who suffer from these devastating seizures.

Highlights.

Circuits of secondarily generalized seizures are more complex than those of primary

After affecting the motor cortex, seizures spread to the striatum

Modulation of the substantia nigra reticulata affects seizures

The corpus callosum aids in seizure generalization

Superficial layer 2/3 can play a critical role in cortico-cortical seizure spread

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Tomson T, Nashef L, Ryvlin P. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: current knowledge and future directions. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:1021–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nashef L, So EL, Ryvlin P, Tomson T. Unifying the definitions of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012;53:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline summary: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors. Neurology 2017;88:1674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Asadi-Pooya AA, Nikseresht A, Yaghoubi E, Nei M. Physical injuries in patients with epilepsy and their associated risk factors. Seizure 2012;21:165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Westbrook GL. Seizures and epilepsy In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Thomas MJ, Siegelbaum SA, Hudspeth AJ, editors. Principles of neural science. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2013. p. 1116–39. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Steriade M, Mccormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 1993;262:679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cain SM, Snutch TP. Voltage-gated calcium channels in epilepsy In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, et al. , editors. Jasper’s basic mechanisms of the epilepsies. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kellaway P Sleep and epilepsy. Epilepsia 1985;26:S15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Steriade M Interneuronal epileptic discharges related to spike-and-wave cortical seizures in behaving monkeys. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1974;37:247–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kostopoulos G, Gloor P, Pellegrini A, Gotman J. A study of the transition from spindles to spike and wave discharge in feline generalized penicillin epilepsy: microphysiological features. Exp Neurol 1981;73:55–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Avoli M, Gloor P, Kostopoulos G, Gotman J. An analysis of penicillin-induced generalized spike and wave discharges using simultaneous recordings of cortical and thalamic single neurons. J Neurophysiol 1984;50:819–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu Z, Vergnes M, Depaulis A, Marescaux C. Involvement of intrathalamic GABAB neurotransmission in the control of absence seizures in the rat. Neuroscience 1992;48:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Norden AD, Blumenfeld H. The role of subcortical structures in human epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2002;3:219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Blumenfeld H, Varghese GI, Purcaro MJ, et al. Cortical and subcortical networks in human secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Brain 2009;132:999–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Enev M, McNally KA, Varghese G, Zubal IG, Ostroff RB, Blumenfeld H. Imaging onset and propagation of ECT-induced seizures. Epilepsia 2007;48:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lothman EW, Collins RC. Kainic acid induced limbic seizures: metabolic, behavioral, electroencephalographic and neuropathological correlates. Brain Res 1981;218:299–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Engel J, Wolfson L, Brown L. Anatomical correlates of electrical and behavioral events related to amygdaloid kindling. Ann Neurol 1978;3:538–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jackson JH. The lumleian lectures on convulsive seizures. Lancet 1890;135:685–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hooks BM, Mao T, Gutnisky DA, Yamawaki N, Svoboda K, Shepherd GM. Organization of cortical and thalamic input to pyramidal neurons in mouse motor cortex. J Neurosci 2013;33:748–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Menezes JR, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007;8:427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shepherd GM. Corticostriatal connectivity and its role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:278–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shepherd GM, Rowe TB. Neocortical lamination: insights from neuron types and evolutionary precursors. Front Neuroanat 2017;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2016;18:7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Turski L, Cavalheiro EA, Bortolotto ZA, Ikonomidou-Turski C, Kleinrok Z, Turski WA. Dopamine-sensitive anticonvulsant site in the rat striatum. J Neurosci 1988;8:4027–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Behere RV, Anjith D, Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Olanzapine-induced clinical seizure: a case report. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009;32:297–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Uvais NA, Sreeraj VS. Seizure associated with olanzapine. J Family Med Prim Care 2018;7:1090–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Koch-Stoecker S Antipsychotic drugs and epilepsy: indications and treatment guidelines. Epilepsia 2002;43:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Alper K, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL, Khan A. Seizure incidence in psychopharmacological clinical trials: an analysis of food and drug administration (FDA) summary basis of approval reports. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Collins RC, Santori EM, Der T, Toga AW, Lothman EW. Functional metabolic mapping during forelimb movement in rat. I. Stimulation of motor cortex. J Neurosci 1986;6:448–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Velíšková J, Moshé SL. Update on the role of substantia nigra pars reticulata in the regulation of seizures. Epilepsy Curr 2006;6:83–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fame RM, Macdonald JL, Macklis JD. Development, specification, and diversity of callosal projection neurons. Trends Neurosci 2011;34:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Van Wagenen WP, Herren RY. Surgical division of commissural pathways in the corpus callosum. Relation to spread of an epileptic attack. Arch NeurPsych 1940;44:740–59. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rappaport ZH, Lerman P. Corpus callosotomy in the treatment of secondary generalizing intractable epilepsy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1988;94:10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wieshmann UC, Milinis K, Paniker J, et al. The role of the corpus callosum in seizure spread: MRI lesion mapping in oligodendrogliomas. Epilepsy Res 2015;109:126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Unterberger I, Bauer R, Walser G, Bauer G. Corpus callosum and epilepsies. Seizure 2016;37:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tanriverdi T, Olivier A, Poulin N, Andermann F, Dubeau F. Long-term seizure outcome after corpus callosotomy: a retrospective analysis of 95 patients. J Neurosurg 2009;110:332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Connors BW. Initiation of synchronized neuronal bursting in neocortex. Nature 1984;310:685–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Telfeian AE, Connors BW. Layer-specific pathways for the horizontal propagation of epileptiform discharges in neocortex. Epilepsia 1998;39:700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Douglas RJ, Martin KA. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004;27:419–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Petersen CC. The functional organization of the barrel cortex. Neuron 2007;56:339–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Thomson AM, Lamy C. Functional maps of neocortical local circuitry. Front Neurosci 2007;1:19–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Weiler N, Wood L, Yu J, Solla SA, Shepherd GM. Top-down laminar organization of the excitatory network in motor cortex. Nat Neurosci 2008;11:360–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wenzel M, Hamm JP, Peterka DS, Yuste R. Reliable and elastic propagation of cortical seizures in vivo. Cell Rep 2017;19:2681–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]