Abstract

The differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into unwanted lineages can generate potential problems in clinical trials. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms, involved in this process, would help prevent unexpected complications. Regulation of gene expression, at the post-transcriptional level, is a new approach in cell therapies. PUMILIO is a conserved post-transcriptional regulator. However, the underlying mechanisms of PUMILIO, in vertebrate stem cells, remain elusive. Here, we show that depletion of PUMILIO2 (PUM2) blocks MSC adipogenesis and enhances osteogenesis. We also demonstrate that PUM2 works as a negative regulator on the 3’ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2 via direct binding. CRISPR/CAS9-mediated gene silencing of Pum2 inhibited lipid accumulation and induced excessive bone formation in zebrafish larvae. Our findings reveal novel roles of PUM2 in MSCs and provide potential therapeutic targets for related diseases.

Keywords: PUMILIO2, JAK2, RUNX2, Mesenchymal stem cells, Cell fate decision

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have multipotent differentiation potential and can be used for clinical trials. However, their differentiation into unwanted lineages may generate potential problems. Thus, understanding the mechanisms related to stem cell fate would help prevent differentiation into unwanted lineages. MSCs can be differentiated into osteocytes and adipocytes, which are believed to originate from a common cell source (Benayahu, Wiesenfeld, & Sapir-Koren, 2019; Pino, Rosen, & Rodriguez, 2012) (Figure 1A). The relationship between osteogenesis and adipogenesis is antagonistic and competitive, and the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs may be involved in various human diseases (Chen et al., 2016; James, 2013; Zhou et al., 2017). Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation are associated with mutually decreased differentiation potential, and the reduction of bone mass, by aging or osteoporosis, may be closely related to an increase of fat mass in the bone marrow (Kim & Ko, 2014; Shen et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2014). A recent study reported that stem cell-based bone regeneration can be impaired by adipocyte accumulation in the bone marrow during obesity or aging (Ambrosi et al., 2017). Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms related to the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation would help develop valuable drug targets (C. Wang et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2013).

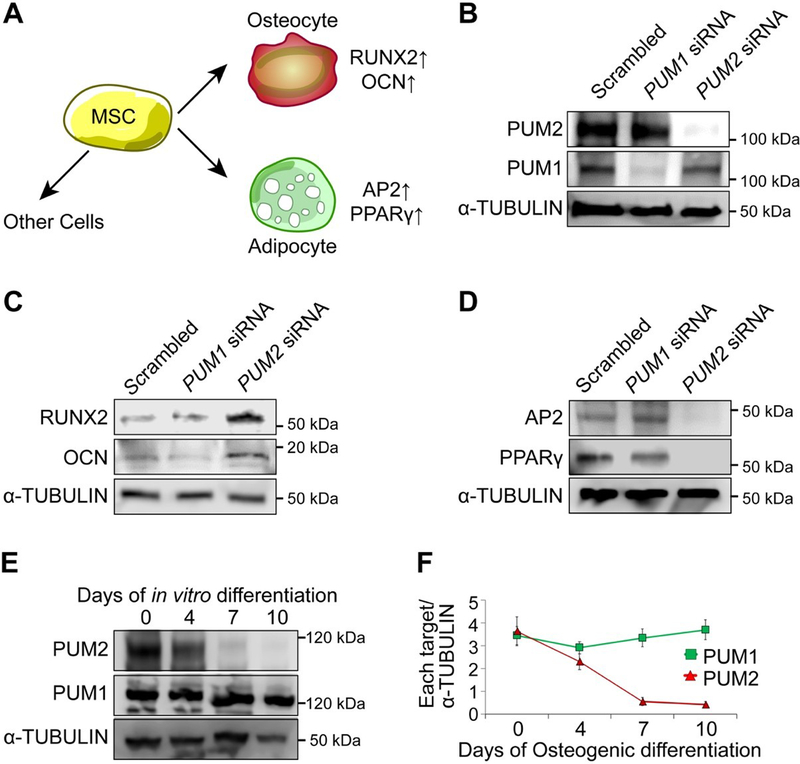

Figure 1. Effects of PUM2 knockdown on MSC differentiation.

A. MSC fate determination and cell fate-specific markers.

B. The protein levels of PUM1 and PUM2 were analysed in MSCs, transfected with non-targeting scrambled, PUM1, or PUM2 siRNA using western blot.

C. The protein levels of RUNX2 and OCN were analysed in MSCs, differentiated into the osteogenic lineage for 7 days using western blot.

D. The protein levels of PPARγ and AP2 were analysed in MSCs, differentiated into the adipogenic lineage for 14 days using western blot.

E. The Protein levels of PUM1 and PUM2 were analysed in MSCs during osteogenic differentiation of MSCs using western blot.

F. Quantification was determined by Image J program (n = 3 experimental replicates). The band intensities were normalized using α-TUBULIN control. ***, p<0.001. See Figure S5 for the original western blots.

Maintenance of stem cell pluripotency and initiation of differentiation require the molecular interplay of transcriptional modulators, epigenetic regulators, and extracellular signalling pathways (Boyer, Mathur, & Jaenisch, 2006; Buganim, Faddah, & Jaenisch, 2013; Yi et al., 2019). Numerous studies have been focused on clarifying the DNA-binding transcription factors and chromatin or protein-modifying enzymes responsible for the fate determination of MSCs (Chambers & Tomlinson, 2009; Hong et al., 2005; Kashyap et al., 2009; Simic et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2014). However, studies on MSC differentiation by post-transcriptional regulatory factors have been lacking. microRNAs (miRNAs) are important post-transcriptional modulators in biological processes (Hobert, 2008). Different miRNAs can function as cell fate determinants to balance the osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in MSCs (Kang & Hata, 2015). Thus, understanding the functions of miRNAs, as post-transcriptional regulators, may provide putative therapeutic targets related to the osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs (Aslani et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019). miRNA-based therapies have disadvantages caused by the instability and off-target effects of mRNAs. Alternatively, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) also bind to RNA molecules to function as post-transcriptional regulators and play roles in such events as mRNA splicing, stabilization, and polyadenylation (Ye & Blelloch, 2014). Some RBPs affect the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, resulting in increased accessibility of the binding targets of miRNAs (Ciafre & Galardi, 2013). Thus, RBPs can function as comprehensive regulators in the post-transcriptional and miRNA-mediated gene regulation. However, little is known about the roles of RBPs in stem cell differentiation, especially in fate determination of MSCs.

The PUMILIO (PUM) proteins are well-conserved eukaryotic RBPs that sequence-specifically bind to the 3’ UTR of their target mRNAs (Wickens, Bernstein, Kimble, & Parker, 2002). The PUM proteins are well-characterized by their highly conserved C-terminal RNA-binding domain, and their binding elements (PBE) are conserved in all eukaryotes (Quenault, Lithgow, & Traven, 2011). PUMILIO1 (PUM1) and 2 (PUM2) have similar structure and can bind to the consensus sequences (UGUAnAUA) present in the 3’ UTR of their target mRNAs, thereby inducing mRNA destabilization or repressing translation (Spassov & Jurecic, 2003b). PUM proteins induce a conformational change in the 3’ UTR region of their target mRNAs to regulate miRNA-mediated gene silencing (Kedde et al., 2010). PUM proteins were first identified as post-transcriptional repressors, regulating the posterior patterning of Drosophila embryos (Murata & Wharton, 1995). In Caenorhabditis elegans, an experimental invertebrate model, the fem-3 binding factor (FBF, a human PUM ortholog) plays an important role in the maintenance of germline stem cells (GSCs) while preventing meiosis and differentiation (Wickens et al., 2002). Thus, the functions of the PUM proteins may be related to stem cell self-renewal (Datla et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the roles of PUM proteins, in vertebrate stem cells, have not been yet delineated. Two human PUM proteins have comparable substrate targets and 88 % of PUM2 targets are also those of PUM1, indicating that PUM1 and PUM2 may function redundantly with respect to binding targets (Galgano et al., 2008). Microarray analyses show that mRNAs, encoding mammalian PUM1 and PUM2, are present in all mammalian stem cells, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs), hematopoietic stem cells, neural stem cells, and MSCs (Sandie et al., 2009), suggesting the conserved role of PUM proteins in stem cells. A few studies have shown that human PUM2 is expressed in the ESCs and germ cells, and it interacts with the deleted in Azoospermia (DAZ), DAZ-like proteins (DAZL), extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK), and p38 (Lee et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2003). Another study, using adipose tissue-derived multipotent stem cells (ACSs) as model system, reports that human PUM2 is involved in the positive regulation of cell proliferation only (Shigunov et al., 2012). However, these studies do not show the mechanistic insights into the functioning of PUM proteins in the regulation of stem cells.

In this study, we show that human PUM2 is involved in fate determination of bone marrow-derived MSCs. Specifically, PUM2 binds to the 3’ UTR of janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) in order to refine the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs. Using zebrafish as our in vivo model system, we confirmed that CRISPR/CAS9-mediated silencing of the Pum2 gene induces excess bone formation and inhibits fat accumulation during larval development. This study reveals a novel role of PUM2 as a post-transcriptional balancer in fate determination of MSCs. PUM2 can be a useful target for diseases such as obesity and osteoporosis with bone marrow adiposity.

RESULTS

The role of PUM2 in MSC differentiation

To evaluate the roles of PUM1 and PUM2 in MSC proliferation and differentiation, we first conducted a siRNA-mediated knockdown study using human bone marrow-derived MSCs. Each siRNA, targeting PUM1 or PUM2, was transfected with MSCs, and then the protein levels of each gene were evaluated by western blot analysis. We confirmed that each siRNA, targeting PUM1 or PUM2, specifically reduced the protein level of each gene (Figure 1B). PUM1 knockdown greatly reduced the proliferation ability of MSCs as previously reported in mammalian stem cells (Naudin et al., 2017; Shigunov et al., 2012; Spassov & Jurecic, 2003a), whereas a PUM2 knockdown did not cause a statistically significant difference in the MSC proliferation ability (data not shown). We next examined the effects of PUM1 or PUM2 knockdown on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs. Early-passage MSCs were transfected with 100 nM of respective siRNAs using Lipofectamine™ 2000 for 6 h, followed by replacing with fresh media. Two days later, the transfected MSCs were then cultured in osteogenic media for 7 days or adipogenic media for 14 days to determine their cell fate-specific differentiation potential using lineage-specific markers (Figure 1A). The protein levels of RUNX2, a major osteogenic transcription factor, and osteocalcin (OCN), a mature differentiation marker of osteogenesis, were higher in PUM2 knockdown MSCs than in PUM1 knockdown MSCs (Figure 1C). By contrast, the protein levels of Adipocyte Protein 2 (AP2), a mature differentiation marker of adipogenesis, and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a major adipogenic transcription factor, were lower only in PUM2 knocked down MSCs (Figure 1D). This result was confirmed by alizarin red S and oil red O staining (data not shown). In light of this observation, it appears that PUM2 knockdown prevented the MSCs from differentiating into the adipogenic lineage. We then checked the changes in protein levels of PUM1 and PUM2 during osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. Although the level of PUM1 protein was not changed during the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, PUM2 level was significantly decreased during the differentiation (Figures 1E and 1F). The expression level of PUM2 protein was maintained until 4 days after osteogenic differentiation, with a gradual decrease over differentiation periods in vitro. Collectively, these results suggest that PUM2 does not have an absolute role in the proliferation of MSCs but may be involved in MSC differentiation.

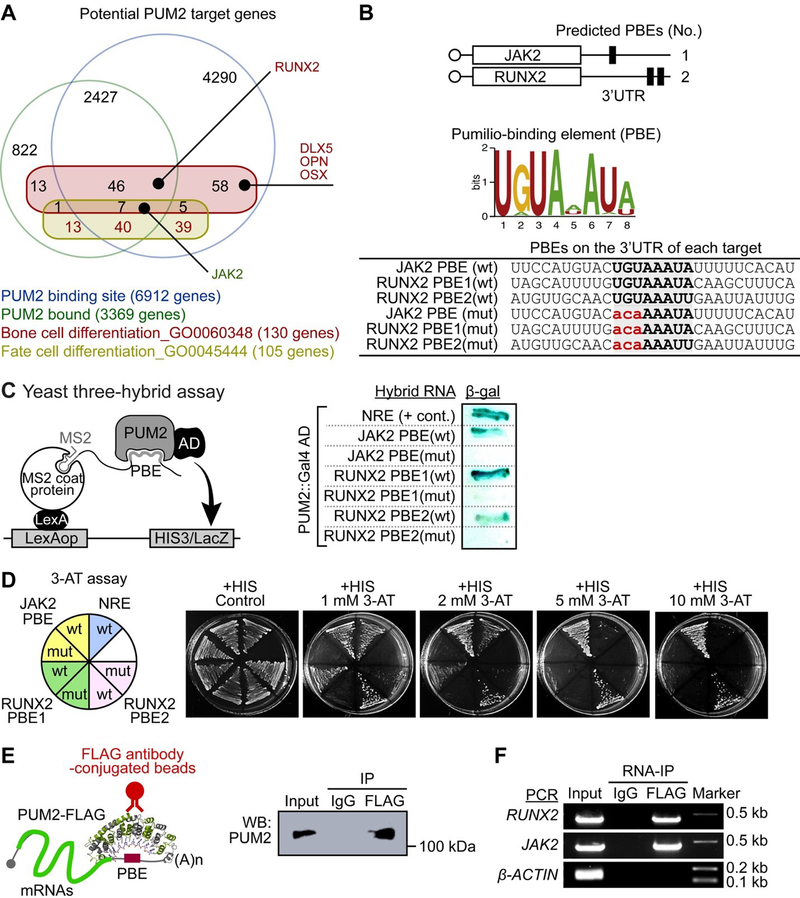

PUM2 is a post-transcriptional regulator of JAK2 and RUNX2

PUM2 was shown to be involved in the balance between MSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation (Figure 1). We preferentially focused on identifying the function of PUM2 in MSC differentiation because the effects of PUM on the self-renewal of stem cells have been well-established (Naudin et al., 2017; Shigunov et al., 2012; Spassov & Jurecic, 2003a). There are, however, no studies on the fate of vertebrate stem cells, especially on the refinement of determination of stem cell lineage. To discover the potential targets of PUM2, we performed gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis (Figure 2A) using the published results and searched the well-known regulators controlling the balance between adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs (Tables S1–S3). Among them, we focused on JAK2 and RUNX2 because they have conserved PBEs on their 3’ UTR (Figure 2B). We assessed whether human PUM2 binds to the 3’ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2 using a yeast three-hybrid system (Figure 2C). The yeast assay confirmed that both JAK2 (wild-type, wt) and RUNX2 (wt) interacted with PUM2 (Figure 2C). However, mutant PBEs (mut) with altered sequences did not (Figures 2B and 2C). The results of the 3-AT assay showed that PUM2 strongly bound to JAK2 and RUNX2 PBEs (wt) (Figure 2D). These results indicate that PUM2 may play important roles in MSC differentiation, balancing the differentiation between osteogenic and adipogenic lineages by sequence-specifically binding to the 3’ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2. To strengthen the evidence for PUM2 binding to the 3ʹ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2 mRNAs, we performed RNA-immunoprecipitation (RNA-IP) in FLAG-tagged vector-transfected MSCs (Figure 2E). Immunoprecipitated FLAG-PUM2 did contain the JAK2 and RUNX2 transcripts (Figure 2F). These data strengthen the evidence for the sequence-specific interaction of PUM2 with JAK2 and RUNX2. Thus, we clearly showed that the PUM2 protein interacts with JAK2 and RUNX2 mRNA by binding to their 3ʹ UTR at the post-transcriptional level.

Figure 2. PUM2 directly interacts with its binding elements (PBE) on the 3’ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2.

A. Gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis using the published results (Bohn et al., 2018; Galgano et al., 2008; Hafner et al., 2010; Morris, Mukherjee, & Keene, 2008) was performed to determine potential PUM2 target. For more details, please see Table S1–S3.

B. Putative PUM binding element (PBE) in JAK2 and RUNX2 3ʹ UTRs and nucleotide sequence of predicted PBE.

C. Yeast three-hybrid assay. RNA-binding activities of the PUM2 protein on the 3ʹ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2 were assayed by measuring β-galactosidase activity using the yeast-three-hybrid system (n = 3 experimental replicates). The consensus UGU PBE sequence was mutated to ACA in all groups (see Figure 2B).

D. Yeast growth, by HIS3 reporter activation, was monitored in the histidine (HIS)+ and HIS- media containing various concentrations of 3-AT (1 mM to 10 mM), a HIS3 competitor (n = 3 experimental replicates).

E. Western blot analysis was performed to confirm IP against FLAG. IP was performed with the anti-FLAG M2 (mouse monoclonal) antibody. Western blot was performed with the anti-PUM2 (rabbit polyclonal) antibody (n = 3 experimental replicates). See Figure S5 for the original western blot.

F. RNA-IP was performed to investigate the direct binding between the PUM2 protein and JAK2 or RUNX2 mRNA. FLAG-PUM2 was immunoprecipitated using the anti-FLAG M2 (mouse monoclonal) antibody in pPLANE-PUM2::FLAG-transfected MSCs; then, RT-PCR was performed, using primers with the 3ʹ UTR containing sequences of JAK2 and RUNX2 mRNA, to confirm the binding between the PUM2 protein and JAK2 and RUNX2 mRNA. β-ACTIN was used as loading control for inputted cDNA (n = 3 experimental replicates).

PUM2 overexpression impairs the osteogenic potential of MSCs and allows adipogenic differentiation of committed MSCs

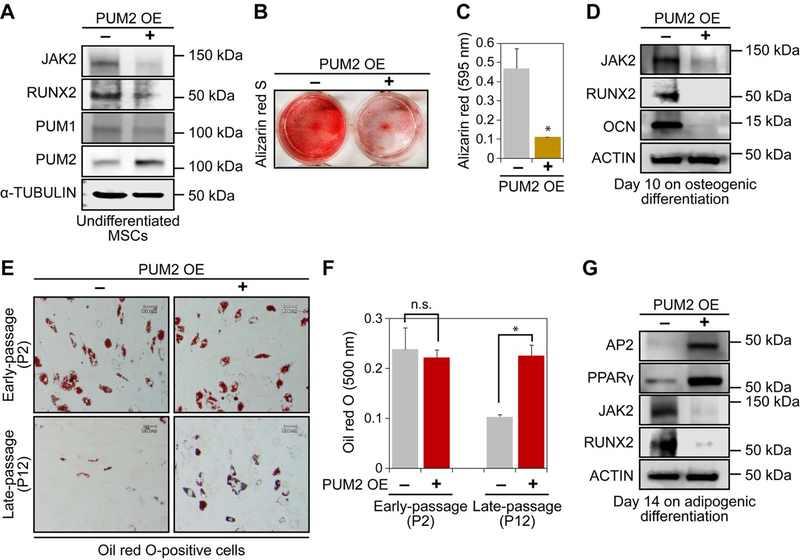

Prior to the PUM2 overexpression study, we confirmed changes in the level of the PUM2 protein during osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs. The levels of PUM2 protein dramatically decreased during differentiation. In particular, the levels of PUM2 were greatly diminished on day 10 of osteogenic differentiation, whereas they were still detectable on day 14 of adipogenic differentiation (Figures S1A and S1B). We employed a FLAG-tagged vector to determine whether an increased expression of PUM2 affected the differentiation potentials of MSCs. PUM2 overexpression was confirmed by western blot; 500 ng per each well of a six-well plate was the ideal concentration for PUM2 overexpression in MSCs (Figure S1C). PUM2 overexpression decreased the levels of JAK2 and RUNX2 in undifferentiated MSCs (Figure 3A). PUM2 overexpression did not affect the colony-forming abilities of MSCs (Figures S1D and S1E) but impaired the osteogenic differentiation potential (Figures 3B and 3C). The levels of JAK2, RUNX2, and OCN were dramatically suppressed by PUM2 overexpression on day 10 of osteogenic differentiation (Figure 3D). Unexpectedly, the adipogenic potential of early-passage MSCs was not altered by overexpression of PUM2 (Figures 3E upper & 3F left). The differentiation potential of late-passage MSCs is committed to osteogenic lineage (Yoon, Kim, Jung, Paik, & Lee, 2011). We asked if the overexpression of PUM2 can rescue the loss of adipogenic potential in late-passage MSCs. The results show that PUM2 overexpression successfully rescued the reduced adipogenic potential of late-passage MSCs (Figures 3E lower & 3F right) and concurrently increased PPARγ and AP2 protein levels (Figure 3G). Therefore, PUM2 acts as a post-transcriptional balancer between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in MSCs.

Figure 3. PUM2 overexpression impairs the osteogenic potential of MSCs and rescues the adipogenic potential of late-passage MSCs that lose their multi-potentiality.

A. Western blot was performed to analyse the protein levels of JAK2, RUNX2, PUM1, and PUM2 in mock- or PUM2-overexpressing, vector-transfected MSCs. The protein expression level of α-TUBULIN was used as a loading control. Each experiment was conducted using MSCs from at least three donors.

B. Each line of vector-transfected MSCs was seeded in 12-well plates (8 × 104 cells per well) to induce osteogenic differentiation. On day 10 of osteogenic differentiation, alizarin red S staining was performed.

C. The stained cells were destained with 10 % cetylpyridinium for quantitative analysis. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm. *P>0.05 compared with mock vector-transfected MSCs.

D. Protein contents of JAK2, RUNX2, and OCN in the MSCs differentiated into osteogenic lineage, were quantified via western blot. The protein expression level of ACTIN was used as a loading control. Each experiment was conducted using MSCs from at least three donors. See Figure S5 for the original western blots.

E. Each line of vector-transfected MSCs was seeded in 12-well plates (8 × 104 cells per well) to induce adipogenic differentiation. On day 14 of adipogenic differentiation, oil red O staining was performed.

F. The stained cells were destained with 100 % isopropanol for quantitative analysis. Absorbance was measured at 500 nm. *P>0.05 compared with mock vector-transfected MSCs.

G. Protein contents of AP2, PPARγ, JAK2, and RUNX2 in the MSCs differentiated into adipogenic lineage, were quantified via western blot. The protein expression level of ACTIN was used as a loading control. See Figure S5 for the original western blots. In C & F, each experiment was conducted using MSCs from at least three donors. The P-values for each experimental group were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test, and the error bars mean s.d.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated silencing of the Pum2 gene inhibits fat accumulation and induces excess bone formation in vivo

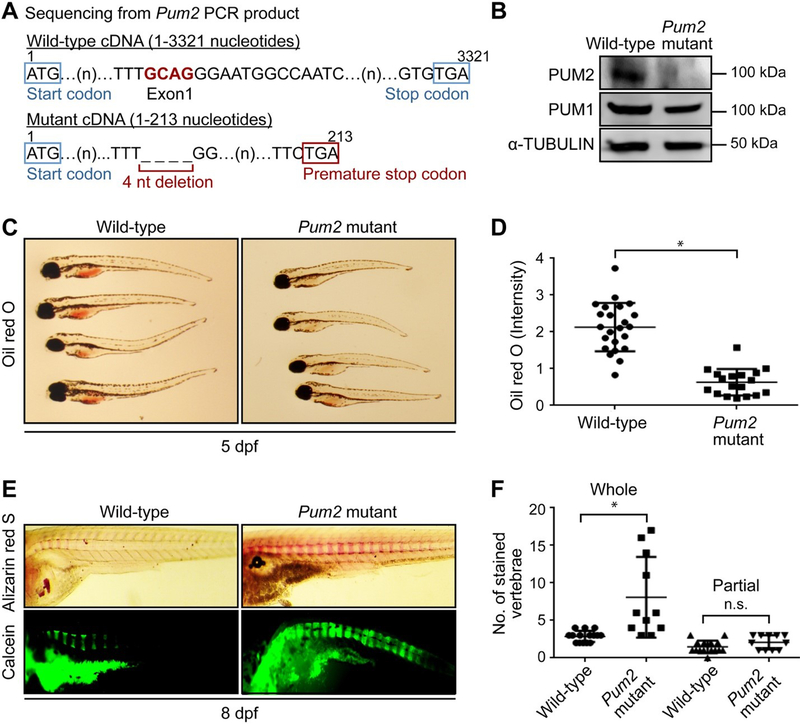

To examine the function of Pum2 during bone development, we obtained zebrafish with the Pum2 gene silenced via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing (Figure S2A). Genomic DNA was amplified by PCR; then, the products were denatured and reannealed to allow for the formation of heteroduplex molecules between wild-type and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated DNA. T7 endonuclease 1 was used to digest the heteroduplex molecules, and we confirmed the resulting cleaved PCR products (Figure S2B). Four nucleotides (GCAG), located in the exon 1 region, were deleted to generate Pum2 deficient zebrafish (Figure S2C). We confirmed the deletion by internal PCR against wild-type Pum2 or mutant Pum2 genomic DNA (Figure S2D). Sequencing of cDNA, obtained from wild-type and Pum2 mutant zebrafish embryos, also showed the deletion of the four nucleotides and generation of a premature stop codon (Figure 4A and S3). Western blot analyses showed that the Pum2 protein was not detected in pum2-mutant zebrafish (Figure 4B). The growth of zebrafish larvae relies entirely on the continuous supply of lipids from their yolk sac during the first few days of development (Carten & Farber, 2009). We compared the degree of fat accumulation in the zebrafish yolk sac, at 5 days post-fertilization (dpf), by using the oil red O stain. CRISPR/CAS9-mediated silencing of Pum2 blocked the accumulation of lipid droplets in the zebrafish yolk sac (Figure 4C). Quantitative results showed that the number of oil red O stained yolk sacs was significantly less in the pum2 mutant larvae than in the wild-type larvae (Figure 4D). At 8 dpf, wild-type larvae exhibited 3 to 4 alizarin red S-positive, and 6 to 8 calcein-positive, whole vertebrae. By contrast, the pum2 mutant showed 3 to 17 alizarin red S-positive whole vertebrae and convergence between calcein-positive segments (Figures 4E and 4F). These results indicate that Pum2 suppresses excessive bone formation and plays a positive role in fat accumulation during the development of zebrafish larvae.

Figure 4. CRISPR/CAS9-mediated gene silencing of Pum2 inhibits fat accumulation and induces excess bone formation in vivo.

A. Sequencing was performed using the cDNA synthesized from the mRNAs of wild-type and putative Pum2 mutant zebrafish embryos. The sequencing result, using cDNA from the Pum2 mutant, shows deletion of four nucleotides (GCAG: 174–177 from the start codon) compared with that of the wild-type, demonstrating that the deletion generates a premature stop codon (TGA: 211–213 from the start codon).

B. Embryos from wild-type and Pum2 mutant zebrafish were collected and used for western blot analysis. The protein levels of zebrafish Pum1 and Pum2 were analysed by western blot. The protein expression level of α-TUBULIN was used as loading control.

C. Oil red O staining was performed on 5 dpf of the wild-type and Pum2 mutant zebrafish larvae. Oil red O clearly stained the yolk sac of the wild-type larvae.

D. Quantitative analysis of the oil red O stained yolk sacs was performed using Image J. *P>0.05 compared with wild-type zebrafish larvae. The P-values were calculated using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, and the error bars mean s.d. n > 20 for each group.

E. Alizarin red S staining and calcein staining were performed on 8 dpf of the wild-type and Pum2 mutant zebrafish larvae.

F. Quantitative analysis for the alizarin red S was performed by counting the numbers of the stained vertebrae (Figure S4). *P>0.05 compared with wild-type zebrafish larvae. The P-values were calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the error bars mean s.d. n > 20 for each group.

In D & F, data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P≤0.05 (ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

Bone marrow adiposity negatively impacts MSC-derived bone regeneration post fracture and hematopoietic reconstitution during aging (Ambrosi et al., 2017). Understating the fate decision of MSCs, residing in the bone marrow, will help provide targets for the treatment of related diseases. Our findings demonstrate that the PUM2 protein is deeply involved in the specification of MSC lineage (Figure 5). Previous studies report that PUM proteins play crucial roles in the proliferation and survival of mammalian stem cells (Naudin et al., 2017; Shigunov et al., 2012; Spassov & Jurecic, 2003a), indicating that the PUM proteins are essential for stem cell maintenance and self-renewal. The founding members of the PUMILIO proteins are Drosophila Pumilio and C. elegans FBF (a mammalian PUMILIO homolog), known as an evolutionarily conserved family of the RBPs (Wickens et al., 2002). Interestingly, Drosophila has only one Pum gene, whereas C. elegans contains 11 pum genes (fbf-1, fbf-2, and puf-3 to puf-11). Most vertebrates, including humans, mice, and zebrafish, have two PUM genes (Spassov & Jurecic, 2002, 2003a). Zebrafish contain an additional Pum gene called puf-A (or Pum3). The C-terminal RNA-binding domain of the Pum3 protein is distinguished from the highly conserved conventional C-terminal RNA-binding domain of other Pum proteins (Kuo et al., 2009). The conserved role of PUM proteins, in most organisms, is to maintain the self-renewal ability of stem cells via maintenance of mitotic cell division and undifferentiated state (Shigunov & Dallagiovanna, 2015). Our results are consistent with the results of previous studies showing that PUM1 is highly involved in the maintenance of MSC self-renewal. Thus, PUM1 may be indispensable in the maintenance of self-renewal capacity of MSCs. However, PUM1 knockdown did not affect the differentiation potential of MSCs, which means that PUM1 is involved only in MSC proliferation. Although we did not clarify why PUM1 is not involved in the differentiation of MSCs, it is possible that PUM1 is not activated in differentiating cells. Kedde et al reported that the RNA-binding activity of PUM1 may be differently modulated in proliferating cells, as opposed to quiescent cells (Kedde et al., 2010). That study suggests that the PUM1 protein is stabilized in cycling cells, and that the phosphorylated PUM1 protein may have strong binding activity with respect to its target.

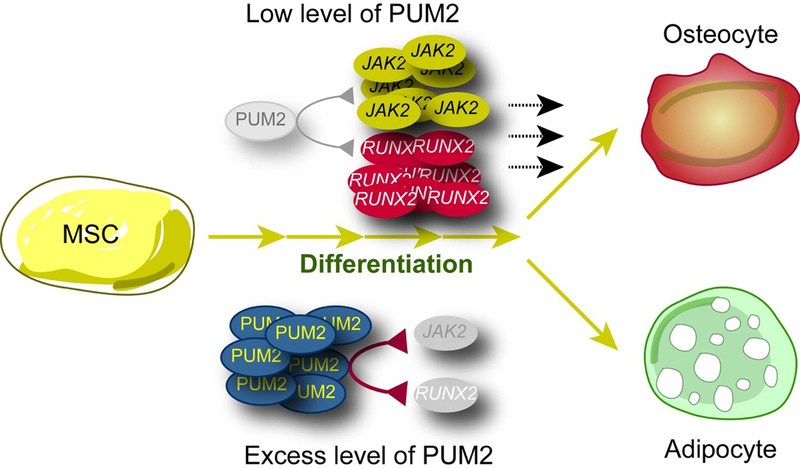

Figure 5. Models representing the roles of PUM2 in promoting osteogenesis and suppressing adipogenesis via binding to its target mRNAs, JAK2 and RUNX2, in MSCs.

PUM2 binds to its PBE sites located at the 3’ UTRs of JAK2 and RUNX2. Depletion of PUM2 enhances JAK2 and RUNX2 expression and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. Thus, targeting PUM2 may enhance the osteogenic potential of MSCs and serve as a target for related diseases.

PUM2 also appears to be involved in the self-renewal of stem cells in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Naudin et al., 2017; Shigunov et al., 2012; Spassov & Jurecic, 2003b). Because PUM modulates self-renewal by suppressing differentiation in germline stem cells (Forbes & Lehmann, 1998; Z. Wang & Lin, 2004), it is possible that PUM2 functions as an inhibitor of stem cell differentiation rather than a modulator of lineage specification. Furthermore, since PUM1 and PUM2 share most of their targets (Galgano et al., 2008), it is possible that they work redundantly with respect to common targets. However, our knockdown study showed that PUM1 and PUM2 act as distinct post-transcriptional regulators that have independent roles in MSC self-renewal and differentiation. Additionally, we observed that PUM2 proteins were still detectable during the adipogenic differentiation of MSCs (Figures S1A and S1B), and that overexpression of PUM2 increased the number of oil red O stained lipid droplets in late-passage human MSCs (Figures 3E and 3F). These findings suggest that PUM2 can work as both a positive and negative regulator of stem cell differentiation. Moreover, PUM2 suppressed the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs (Figures 3B and 3C) but did not affect MSC proliferation (Figures S1D and S1E); this indicates that PUM2 is a balancer that refines differentiation between osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. Understanding the molecular mechanisms, involved in the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation, is important in the study of MSCs because an imbalance between the two lineages can cause various aging and metabolism-related diseases. Although numerous studies have clarified the molecular mechanisms, and found new targets involved in the selection between the two lineages (Chen et al., 2016), more studies are required to fully understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the choice between the two lineages in MSCs. We identified PUM2 as a new regulator that balances the differentiation between the osteogenic and adipogenic lineages (Figure 5). PUM2 interacted with PBEs on the 3’ UTR of JAK2 and RUNX2, a positive regulator of osteogenesis and negative regulator of adipogenesis, respectively (Darvin, Joung, & Yang, 2013; Dieudonne et al., 2013; Ducy, Zhang, Geoffroy, Ridall, & Karsenty, 1997; James, 2013; Joung et al., 2012; Karsenty, Kronenberg, & Settembre, 2009; Komori et al., 1997; Long, 2011; Otto et al., 1997). The knockdown of PUM2 completely suppressed the in vitro and in vivo adipogenesis, while enhancing the in vitro and in vivo osteogenic potential, of MSCs (Figure 1). Importantly, we found that PUM2 functions as an upstream regulator of JAK2 and RUNX2. RUNX2 is a downstream gene of the JAK2-STAT5b pathway (Darvin et al., 2013; Dieudonne et al., 2013; Joung et al., 2012). We thus hypothesized that the PUM2-mediated phenotypes of MSC differentiation may be regulated by RUNX2 under the control of JAK2. Taken together, we conclude that PUM2 is an upstream modulator of the JAK2 and RUNX2 pathways responsible for controlling the balance between osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in MSCs (Figure 5).

In summary, our findings indicate that PUM2 is a molecular switch that negatively regulates RUNX2 and JAK2 to exert opposing effects on the bone and fat formation by MSCs (Figure 5). Thus, our data suggest that targeting PUM2 can be a promising approach for stem cell-mediated regenerative medicine and for the treatment of metabolic diseases such as obesity and osteoporosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Bone marrow-derived MSCs (ATCC PCS-500–041) cell lines were purchased from the Global Bioresource Center (ATCC) and were also provided by Dr. Darwin Prockop’s lab (Texas A&M University – NIH OD011050–15: Preparation and Distribution of Adult Stem Cells). MSCs were maintained in low-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM-LG; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10 % foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island NY, USA) and 1 % antibiotic–antimycotic solution (Invitrogen), at 37°C and 5 % CO2. The MSCs were replated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 and were sub-cultured when they were 80 % confluent.

RNA interference

Scrambled, PUM1 and PUM2 siRNAs were purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, South Korea; http://sirna.bioneer.co.kr/). The information on the siRNAs, used in this study, is listed in the Table S4. Briefly, MSCs were cultured to 70–80% confluence in 6-well plates and transfected with 100 nM of each siRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 6 h of transfection, the media were replaced with fresh media. Two days later, the transfected MSCs were then cultured in osteogenic or adipogenic media to determine their cell fate-specific differentiation potential (see a method for osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation below).

Overexpression of PUM2

The pPLANE (FLAG-tagged) expression vector was kindly provided by the Jamie A. Thomson Laboratory (University of Wisconsin, Madison WI, USA). PUM2 was amplified from human cDNA and cloned into a pPLANE vector. The PUM2::FLAG construct contained a PUM2 protein coding region, plus three copies of FLAG sequences, as has been previously described (Lee et al., 2007). A vector with no insert was used as control in each case. Briefly, MSCs were plated to obtain 70–80 % confluency in 6-well plates and transfected with PUM2 expression vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 6 h of transfection, the media were replaced with fresh media.

Osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation

The differentiation media, used in this study, have been described previously (Yoon et al., 2011). Briefly, BM-MSCs were seeded at 83 × 104 cells/well in 12-well plates. To determine the differentiation activity for each lineage, we used alizarin red S for osteogenic differentiation and oil red O for adipogenic differentiation. Briefly, for alizarin red S staining, after being fixed in ice-cold 70 % ethanol, 1 ml of freshly prepared 3 % alizarin red S solution (wt/vol) (Sigma) was added, and the cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min. For quantitative analysis, the cells were destained with 10 % cetylpyridinium chloride monohydrate (Sigma) for 30 min, and the absorbance of the stained cells was detected at 595 nm. To stain the lipid droplets by oil red O, BM-MSCs were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin, then 1 ml of 0.18 % oil red O solution (Sigma) was added and incubated for 1 h. For quantitative analysis, the stained cells were destained with 100 % isopropanol for 30 min, and the absorbance was detected at 500 nm.

Yeast three-hybrid and 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (AT) assays

Three-hybrid assays were performed as described previously (Lee, Hook, Lamont, Wickens, & Kimble, 2006). The sequences for the 3’ UTR regions of each target, cloned using the PIIIA/MS2–2 vector, are listed in Table S5. These vectors, containing the target sequences of each 3’ UTR, were co-transformed with PUM2 in a pACTII vector into YBZ-1 yeast strain. The levels of β-galactosidase were assayed in at least three independent experiments. The levels of 3-AT resistance were determined by assaying multiple transformants at four different concentrations of 3-AT, from 1 to 10 mM.

RNA-immunoprecipitation (IP) and RT-PCR

RNA-IP and RT-PCR assays were performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2007). Briefly, the MSCs were plated to obtain 70–80 % confluency in 6-well plates and transfected with 3X FLAG-tagged pPLANE-PUM2 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 6 h of transfection, the media were replaced with fresh media. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested for IP. The harvested cells were resuspended in 5 mL of ice-cold PBS, and then 143 μl of 37 % formaldehyde was added to cross-link protein-RNA for 10 min. After adding 685 μl of 2M glycine to block the activity of formaldehyde, the cells were centrifuged. After washing with ice-cold PBS, IP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 0.4 m NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 % tritonX-100, and 10 % glycerol) and a cocktail of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/protease inhibitor/RNase inhibitor were added to the cell pellets. After sonication, the cell lysates were prepared for IP. Blocked FLAG antibody- or IgG-conjugated beads (Sigma) were added to the cell lysates and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads with IP lysis buffer, RIP buffer (IP lysis buffer + 1% SDS) and an RNase inhibitor were added to the beads. After incubating the beads for 1 h at 70°C to reverse the cross-link, RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and reverse-transcribed by an Omniscript kit (Qiagen). PCR was conducted using a cDNA template for JAK2 and RUNX2 in the linear range (40 cycles), with gene-specific primers designed so that one primer spanned an exon-exon junction. PCR products were resolved on a 1 % agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The information on the primers used is presented in the Table S6.

Western blot

MSCs were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA); 30 mg of protein was analysed by 10 % sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Sigma). Transferred membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk (BD, Sparks, MD, USA) or 5 % BSA (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated for approximately 10 h with antibodies against PUM1 (GeneTex, Inc., CA, USA), PUM2 (human; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), PUM2 (zebrafish; Biorbyt Ltd, Cambridge, UK), JAK2 (EMD Millipore, San Diego, CA, USA), OCN (Abcam), RUNX2 (EMD Millipore), PPARγ (EMD Millipore), AP2 (Abcam), and FLAG (Sigma). Membranes were further probed with antibodies against α-TUBULIN (Sigma) or actin (MP Biomedicals, Eschwege, Germany), which served as loading controls.

CRISPR/CAS9-mediated gene silencing and maintenance of zebrafish

Gene editing of Pum2 was performed using the CRISPR/Cas9 system optimized for zebrafish genome editing, as described by Jao et al (Jao, Wente, & Chen, 2013). Briefly, to establish Pum2 mutant zebrafish lines, gRNA, targeting the first exon of Pum2, was designed, and deletion was induced by injection with Cas9 mRNA in the zebrafish embryo. Several mutant lines were established using Pum2 gRNA with the sequence 5’-GGAGGTGGCAGGCAGGTACC; the line used in current study is a four base-pair deletion mutant with a premature stop codon. Details and characterization of this mutant are presented in Figures S2, S3, and Table S7. Zebrafish maintenance was performed as previously described (Liu, Brewer, Chen, Hong, & Zhu, 2017; Zhu et al., 2015).

Oil red O staining in zebrafish larvae

Zebrafish larvae, at 5 dpf, were collected, and then fixed in 3.7 % formaldehyde for 2 h. After washing with PBS, the larvae were placed in 60 % isopropanol for 10 min without additional washing; the larvae were stained with 0.16 % oil red O (Sigma) and dissolved in 60 % isopropanol for 12 h. After washing three times with PBS, the stained larvae were destained with 100 % isopropanol for 30 min. After washing several times, the larvae were stored in glycerol until imaging.

Alizarin red S staining in zebrafish larvae

Zebrafish larvae, at 8 dpf, were collected, and then fixed in 3.7 % formaldehyde. After rocking at room temperature for 2 h, the fixative was removed. The fixed larvae were washed and dehydrated, using 50 % ethanol, while rocking for 10 min. After removing the 50 % ethanol, a 0.5 % alizarin red S (Sigma) solution, dissolved in 70 % ethanol/40 mM MgCl2, was added to the larvae, which was then rocked at room temperature overnight. To remove pigmentation, a bleaching solution (1.5 % H2O2 and 1 % KOH) was added to the larvae and the larvae-containing tubes sat with lids open for 20 min. For clearing, a 20 % glycerol/0.25 % KOH solution was added to the tubes and allowed to rock for 30 min after removing the bleaching solution. The 20 % glycerol / 0.25 % KOH solution was replaced with a 50 % glycerol/0.25 % KOH solution, and then the tubes were rocked at room temperature for 2 h. The cleared larvae were stored in the same solution until imaging.

Calcein staining in zebrafish larvae

For calcein staining, live zebrafish larvae, at 8 dpf, were immersed in 0.2 % calcein (Sigma) solution (pH 7.2) for 10 min. The calcein-stained larvae were immersed in dH2O for 10 min to diffuse the excess calcein out of the tissues. This step was repeated three times. The larvae were anesthetized in 10 % tricaine and then placed on glass slides with glycerol. The mounted larvae were imaged using a filter set for the green fluorescent protein.

Data analysis

For statistical analysis, all experiments were performed in triplicate using samples from at least three donors. Student’s t-tests were used to assess differences between two groups. The statistical significance of the differences among three or more groups was calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Bonferroni correction. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Dongliang Chen (UNC-CH), Dr. Dongteng Liu (ECU), Dr. Young Chul Kwon (ECU), Dr. Dong Suk Yoon (ECU), and Mohammad Alfhili (King Saud University) for Bioinformatic analysis, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Pum2 knockout, MSC culture, and critical reading, respectively.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported in part by the NIH (GM112174-01A1) and the Brody Brothers Grant (21602-664261) to M.H.L. and by the NIH (GM100461-02) to Y.Z.

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosi TH, Scialdone A, Graja A, Gohlke S, Jank AM, Bocian C, . . . Schulz TJ (2017). Adipocyte Accumulation in the Bone Marrow during Obesity and Aging Impairs Stem Cell-Based Hematopoietic and Bone Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslani S, Abhari A, Sakhinia E, Sanajou D, Rajabi H, & Rahimzadeh S (2019). Interplay between microRNAs and Wnt, transforming growth factor-beta, and bone morphogenic protein signaling pathways promote osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol, 234(6), 8082–8093. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayahu D, Wiesenfeld Y, & Sapir-Koren R (2019). How is mechanobiology involved in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation toward the osteoblastic or adipogenic fate? J Cell Physiol, 234(8), 12133–12141. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn JA, Van Etten JL, Schagat TL, Bowman BM, McEachin RC, Freddolino PL, & Goldstrohm AC (2018). Identification of diverse target RNAs that are functionally regulated by human Pumilio proteins. Nucleic Acids Res, 46(1), 362–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Mathur D, & Jaenisch R (2006). Molecular control of pluripotency. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 16(5), 455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buganim Y, Faddah DA, & Jaenisch R (2013). Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Rev Genet, 14(6), 427–439. doi: 10.1038/nrg3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carten JD, & Farber SA (2009). A new model system swims into focus: using the zebrafish to visualize intestinal metabolism in vivo. Clin Lipidol, 4(4), 501–515. doi: 10.2217/clp.09.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I, & Tomlinson SR (2009). The transcriptional foundation of pluripotency. Development, 136(14), 2311–2322. doi: 10.1242/dev.024398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, Jiang M, Cao G, Yang Q, . . . Shi Y (2016). Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ, 23(7), 1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciafre SA, & Galardi S (2013). microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins: a complex network of interactions and reciprocal regulations in cancer. RNA Biol, 10(6), 935–942. doi: 10.4161/rna.24641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvin P, Joung YH, & Yang YM (2013). JAK2-STAT5B pathway and osteoblast differentiation. JAKSTAT, 2(4), e24931. doi: 10.4161/jkst.24931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datla US, Scovill NC, Brokamp AJ, Kim E, Asch AS, & Lee MH (2014). Role of PUF-8/PUF protein in stem cell control, sperm-oocyte decision and cell fate reprogramming. J Cell Physiol, 229(10), 1306–1311. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieudonne FX, Severe N, Biosse-Duplan M, Weng JJ, Su Y, & Marie PJ (2013). Promotion of osteoblast differentiation in mesenchymal cells through Cbl-mediated control of STAT5 activity. Stem Cells, 31(7), 1340–1349. doi: 10.1002/stem.1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, & Karsenty G (1997). Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell, 89(5), 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A, & Lehmann R (1998). Nanos and Pumilio have critical roles in the development and function of Drosophila germline stem cells. Development, 125(4), 679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galgano A, Forrer M, Jaskiewicz L, Kanitz A, Zavolan M, & Gerber AP (2008). Comparative analysis of mRNA targets for human PUF-family proteins suggests extensive interaction with the miRNA regulatory system. PLoS One, 3(9), e3164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, . . . Tuschl T (2010). Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell, 141(1), 129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O (2008). Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science, 319(5871), 1785–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1151651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Hwang ES, McManus MT, Amsterdam A, Tian Y, Kalmukova R, . . . Yaffe MB (2005). TAZ, a transcriptional modulator of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science, 309(5737), 1074–1078. doi: 10.1126/science.1110955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AW (2013). Review of Signaling Pathways Governing MSC Osteogenic and Adipogenic Differentiation. Scientifica (Cairo), 2013, 684736. doi: 10.1155/2013/684736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao LE, Wente SR, & Chen W (2013). Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(34), 13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung YH, Lim EJ, Darvin P, Chung SC, Jang JW, Do Park K, . . . Yang YM (2012). MSM enhances GH signaling via the Jak2/STAT5b pathway in osteoblast-like cells and osteoblast differentiation through the activation of STAT5b in MSCs. PLoS One, 7(10), e47477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, & Hata A (2015). The role of microRNAs in cell fate determination of mesenchymal stem cells: balancing adipogenesis and osteogenesis. BMB Rep, 48(6), 319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty G, Kronenberg HM, & Settembre C (2009). Genetic control of bone formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 25, 629–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap V, Rezende NC, Scotland KB, Shaffer SM, Persson JL, Gudas LJ, & Mongan NP (2009). Regulation of stem cell pluripotency and differentiation involves a mutual regulatory circuit of the NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 pluripotency transcription factors with polycomb repressive complexes and stem cell microRNAs. Stem Cells Dev, 18(7), 1093–1108. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedde M, van Kouwenhove M, Zwart W, Oude Vrielink JA, Elkon R, & Agami R (2010). A Pumilio-induced RNA structure switch in p27–3’ UTR controls miR-221 and miR-222 accessibility. Nat Cell Biol, 12(10), 1014–1020. doi: 10.1038/ncb2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Ko J (2014). A novel PPARgamma2 modulator sLZIP controls the balance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis during mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ, 21(10), 1642–1655. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, . . . Kishimoto T (1997). Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell, 89(5), 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MW, Wang SH, Chang JC, Chang CH, Huang LJ, Lin HH, . . . Yu J (2009). A novel puf-A gene predicted from evolutionary analysis is involved in the development of eyes and primordial germ-cells. PLoS One, 4(3), e4980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Hook B, Lamont LB, Wickens M, & Kimble J (2006). LIP-1 phosphatase controls the extent of germline proliferation in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J, 25(1), 88–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Hook B, Pan G, Kershner AM, Merritt C, Seydoux G, . . . Kimble J (2007). Conserved regulation of MAP kinase expression by PUF RNA-binding proteins. PLoS Genet, 3(12), e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Wu Y, Yang H, Hong P, Fang X, & Hu Y (2019). H19/miR-30a/C8orf4 axis modulates the adipogenic differentiation process in human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DT, Brewer MS, Chen S, Hong W, & Zhu Y (2017). Transcriptomic signatures for ovulation in vertebrates. Gen Comp Endocrinol, 247, 74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long F (2011). Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 13(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm3254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore FL, Jaruzelska J, Fox MS, Urano J, Firpo MT, Turek PJ, . . . Pera RA. (2003). Human Pumilio-2 is expressed in embryonic stem cells and germ cells and interacts with DAZ (Deleted in AZoospermia) and DAZ-like proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 100(2), 538–543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234478100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AR, Mukherjee N, & Keene JD (2008). Ribonomic analysis of human Pum1 reveals cis-trans conservation across species despite evolution of diverse mRNA target sets. Mol Cell Biol, 28(12), 4093–4103. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00155-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, & Wharton RP (1995). Binding of pumilio to maternal hunchback mRNA is required for posterior patterning in Drosophila embryos. Cell, 80(5), 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naudin C, Hattabi A, Michelet F, Miri-Nezhad A, Benyoucef A, Pflumio F, . . . Lauret E (2017). PUMILIO/FOXP1 signaling drives expansion of hematopoietic stem/progenitor and leukemia cells. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-747436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, . . . Owen MJ (1997). Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell, 89(5), 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pino AM, Rosen CJ, & Rodriguez JP (2012). In osteoporosis, differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) improves bone marrow adipogenesis. Biol Res, 45(3), 279–287. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602012000300009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenault T, Lithgow T, & Traven A (2011). PUF proteins: repression, activation and mRNA localization. Trends Cell Biol, 21(2), 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandie R, Palidwor GA, Huska MR, Porter CJ, Krzyzanowski PM, Muro EM, . . . Andrade-Navarro MA. (2009). Recent developments in StemBase: a tool to study gene expression in human and murine stem cells. BMC Res Notes, 2, 39. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Chen J, Gantz M, Punyanitya M, Heymsfield SB, Gallagher D, . . . Gilsanz V (2012). MRI-measured pelvic bone marrow adipose tissue is inversely related to DXA-measured bone mineral in younger and older adults. Eur J Clin Nutr, 66(9), 983–988. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigunov P, & Dallagiovanna B (2015). Stem Cell Ribonomics: RNA-Binding Proteins and Gene Networks in Stem Cell Differentiation. Front Mol Biosci, 2, 74. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigunov P, Sotelo-Silveira J, Kuligovski C, de Aguiar AM, Rebelatto CK, Moutinho JA, . . . Dallagiovanna B (2012). PUMILIO-2 is involved in the positive regulation of cellular proliferation in human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Dev, 21(2), 217–227. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simic P, Zainabadi K, Bell E, Sykes DB, Saez B, Lotinun S, . . . Guarente L (2013). SIRT1 regulates differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by deacetylating beta-catenin. EMBO Mol Med, 5(3), 430–440. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassov DS, & Jurecic R (2002). Cloning and comparative sequence analysis of PUM1 and PUM2 genes, human members of the Pumilio family of RNA-binding proteins. Gene, 299(1–2), 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassov DS, & Jurecic R (2003a). Mouse Pum1 and Pum2 genes, members of the Pumilio family of RNA-binding proteins, show differential expression in fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. Blood Cells Mol Dis, 30(1), 55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassov DS, & Jurecic R (2003b). The PUF family of RNA-binding proteins: does evolutionarily conserved structure equal conserved function? IUBMB Life, 55(7), 359–366. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001603093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Meng H, Wang X, Zhao C, Peng J, & Wang Y (2016). Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Osteoblasts and Adipocytes and its Role in Treatment of Osteoporosis. Med Sci Monit, 22, 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, & Lin H (2004). Nanos maintains germline stem cell self-renewal by preventing differentiation. Science, 303(5666), 2016–2019. doi: 10.1126/science.1093983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Li H, Wang S, Li T, Fan J, Liang X, . . . Zhao RC. (2014). let-7 enhances osteogenesis and bone formation while repressing adipogenesis of human stromal/mesenchymal stem cells by regulating HMGA2. Stem Cells Dev, 23(13), 1452–1463. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M, Bernstein DS, Kimble J, & Parker R (2002). A PUF family portrait: 3’UTR regulation as a way of life. Trends Genet, 18(3), 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Guan M, Jia J, Dai W, Lay YA, Amugongo S, . . . Lane NE (2013). Reversing bone loss by directing mesenchymal stem cells to bone. Stem Cells, 31(9), 2003–2014. doi: 10.1002/stem.1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, & Blelloch R (2014). Regulation of pluripotency by RNA binding proteins. Cell Stem Cell, 15(3), 271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X, Wu P, Liu J, Gong Y, Xu X, & Li W (2019). Identification of the potential key genes for adipogenesis from human mesenchymal stem cells by RNA-Seq. J Cell Physiol. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DS, Choi Y, Jang Y, Lee M, Choi WJ, Kim SH, & Lee JW (2014). SIRT1 directly regulates SOX2 to maintain self-renewal and multipotency in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells, 32(12), 3219–3231. doi: 10.1002/stem.1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DS, Kim YH, Jung HS, Paik S, & Lee JW (2011). Importance of Sox2 in maintenance of cell proliferation and multipotency of mesenchymal stem cells in low-density culture. Cell Prolif, 44(5), 428–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00770.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang S, Qi Q, Yang X, Zhu E, Yuan H, . . . Wang B (2017). Nuclear factor I-C reciprocally regulates adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation via control of canonical Wnt signaling. FASEB J. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600975RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Liu D, Shaner ZC, Chen S, Hong W, & Stellwag EJ (2015). Nuclear progestin receptor (pgr) knockouts in zebrafish demonstrate role for pgr in ovulation but not in rapid non-genomic steroid mediated meiosis resumption. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 6, 37. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.