Abstract

Recent research suggests combining putative reinforcers for problem behavior into a single, synthesized contingency may increase efficiency in identifying behavioral function relative to traditional functional analysis (FA; Slaton, Hanley, & Raftery, 2017). Other research suggests potential shortcomings (e.g., false-positive outcomes; Fisher, Greer, Romani, Zangrillo, & Owen, 2016 ) of synthesized contingency analysis (SCA). In prior comparisons of traditional FAs and SCAs investigators could not ascertain with certainty the true function(s) of the participants’ problem behavior for use as the criterion variable. We conducted a translational study to circumvent this limitation by training a specific function for a surrogate destructive behavior prior to conducting a traditional FA and SCA. The traditional FA correctly identified the established function of the target response in all six cases and produced no iatrogenic effects. The SCA produced differentiated results in all cases and iatrogenic effects in three of six cases. We discuss these finding in terms the mechanisms that may promote iatrogenic effects.

Keywords: behavioral assessment, functional analysis, iatrogenic effects, induction of novel functions, interview informed synthesized contingency analysis

The first line intervention for severe problem behavior typically involves the prescription of psychoactive medications (30% to 70% of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) receive psychoactive medications and approximately 30% receive two or more medications; Goin-Kochel, Meyers, & Mackintosh, 2007; Mandell et al., 2008; Oswald & Sonenklar 2007; Rosenberg et al. 2010). One effective alternative or adjunct to medication is function-based intervention in which the behavior analyst conducts a functional analysis (FA) and then uses the results to prescribe a treatment that matches the function of the individual’s problem behavior (Beavers, Iwata, & Lerman, 2013; Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003). Functional analysis allows clinicians to identify the variables that evoke and maintain destructive behavior, and FA has increased the prevalence of reinforcement-based interventions and decreased the prevalence of punishment procedures(e.g., Greer, Fisher, Saini, Owen, & Jones, 2016), as well as decreased the reliance on medications to treat problem behavior (e.g., Aman et al., 2009). Nevertheless, few children with problem behavior who could benefit from FA actually receive it (Roane, Fisher, & Carr, 2016).

Traditional FA methods (i.e., methods first described by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman, 1982/1994) use controlled, single-case experimental designs to manipulate systematically and independently variables that potentially reinforce problem behavior, such as attention (e.g., Fisher, DeLeon, Rodriguez‐Catter, & Keeney, 2004), escape (e.g., LaRue, Stewart, Piazza, Volkert, Patel, & Zeleny, 2011; Zarcone et al., 1993), or access to tangibles (e.g., Briggs, Akers, Greer, Fisher, & Retzlaff, 2018; Hagopian, Wilson, & Wilder, 2001). This allows clinicians to (a) determine the influence of each environmental variable on problem behavior and (b) develop efficacious and individualized treatment (Betz & Fisher, 2011).

Researchers have recommended that practitioners use FA to guide treatment selection for problem behavior whenever possible rather than indirect or direct assessments (e.g., Iwata & Dozier, 2008). This is because multiple studies have shown indirect assessments to be unreliable, and because descriptive assessments, though generally more reliable than indirect methods, do not distinguish well between positive and negative reinforcement and often implicate attention as a reinforcer when it is a correlated but nonfunctional consequence of problem behavior (Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Thompson & Iwata, 2007). Despite the limitations of indirect and descriptive assessments, most practitioners continue to use these methods rather than FA, in part because they view FA procedures as overly time consuming and requiring highly-trained staff (Oliver, Pratt, & Normand, 2015).

Recently, researchers have recommended that practitioners use an efficient alternative to traditional FA in which the behavior analyst develops a synthesized contingency analysis (SCA) based on a caregiver interview (Hanley, 2012), and in some cases, informal observations under conditions similar to an FA (Hanley, Jin, Vanselow, & Hanratty, 2014; Jessel, Ingvarsson, Metras, Kirk, & Whipple, 2018). Based on the results of these preassessments, the behavior analyst then develops a single test condition that combines all of the identified putative reinforcers for problem behavior (e.g., escape to tangibles) and a single control condition in which the same putative reinforcers are provided freely and continuously (e.g., no demands and free access tangibles). A number of studies have shown that treatment packages based on outcomes from an interview-informed SCA (IISCA) have produced marked reductions in problem behavior (Hanley et al., 2014; Ghaemmaghami, Hanley, Jin, & Vanselow, 2016; Santiago, Hanley, Moore, & Jin, 2016). Additionally, Slaton and Hanley (2018) reviewed synthesis during FA and treatment of problem behavior and found an average reduction of 90% from baseline responding in the final phase when a synthesized treatment was used. Although these outcomes are promising, practitioners must consider the potential benefits of an assessment (e.g., time saved) in conjunction with its potential risks.

Combining multiple putative reinforcers into a single contingency has at least two potential risks. First, there is a risk for false-positive outcomes because the putative reinforcers of an IISCA are selected based on an indirect assessment of unknown reliability and validity (Hanley, 2012; also see the discussion of conflicting informant reports during the IISCA on pp. 259–260 in Slaton et al., 2017). Fisher, Greer, Romani, Zangrillo, and Owen (2016) evaluated this potential risk of an IISCA by examining the results of a traditional FA and an IISCA in five consecutive patients admitted to a university-based program for the treatment of severe problem behavior. The IISCA identified multiple consequences that did not maintain problem behavior when those consequences were evaluated in isolation during the traditional FA (i.e., false-positive outcomes). Fisher et al. also tested whether the results of the FA and the IISCA supported the assumption of a traditional FA that problem behavior is typically reinforced by contingencies operating independently, or the assumption of an SCA that multiple simultaneous consequences interactively reinforced problem behavior. Findings would support an interactive effect if higher levels of aggression occur when aggression simultaneously produces attention and escape than when it produces either of these consequences in isolation. Four participants showed sensitivity to an individual contingency (e.g., tangible reinforcement), but not increased levels of problem behavior or more differentiated results when the investigators combined multiple reinforcers (e.g., escape to tangible items) using an IISCA. However, a ceiling effect may have prevented identification of interactive effects between the synthesized contingencies, given that participants responded at efficient levels during the individual contingency test conditions in the traditional FA. Nevertheless, the results showed that the individual contingency proved sufficient to maintain destructive behavior at high levels throughout the assessment for four of five participants. The fifth participant never displayed problem behavior during either the traditional FA or the IISCA. Greer, Mitteer, Briggs, Fisher, & Sodawasser (conditionally accepted) replicated and extended these findings with 12 consecutive cases.

The second potential risk of an SCA is that combining a functional reinforcer (e.g., escape) with a nonfunctional, but highly preferred stimulus (e.g., an iPad) has the potential to induce a novel function (e.g., teaching the individual to access the iPad via problem behavior). In medicine, the term iatrogenic effect is used when the implementation of a procedure results in a new symptom or condition (Centorrino et al., 2004). Researchers have examined the risk of inducing a novel function during FA within the context of traditional FA. Shirley, Iwata, and Kahng (1999) conducted a traditional FA, and found automatic reinforcement and tangible reinforcement, in the form of access to preferred stimuli such as a puzzle, maintained a participant’s hand mouthing. However, observation of the individual in the natural environment indicated that caregivers only delivered a towel contingent upon hand mouthing. When Shirley et al. provided access to a towel contingent on hand mouthing in the tangible test condition of a traditional FA, hand mouthing decreased, suggesting that the original finding of a tangible function represented a false positive or an iatrogenic effect. Other researchers have suggested iatrogenic effects may be most likely during FA if a tangible condition is included (Rooker, Iwata, Harper, Fahmie, & Camp, 2011). However, Jessel, Hausman, Schidt, Darnell, and Kahng (2014) reported a case of a potential iatrogenic effect during the escape condition of a traditional FA.

Synthesized contingency analyses may be more susceptible to an iatrogenic effect in the form of inducing a novel function of problem behavior than a traditional FA because a previously nonfunctional, but preferred stimulus may be delivered multiple times contingent on problem behavior if it is included in the combined contingency. For example, if the target behavior is actually maintained by escape alone, and the test condition of an SCA arranges escape to computer as the consequence, then introduction of demands would likely evoke the target behavior. Once the target behavior occurs, both escape and access to the computer would be delivered leading to multiple deliveries of access to the computer immediately following the target behavior. By contrast, the nonfunctional, but preferred stimulus is not likely to be delivered multiple times contingent on problem behavior in a traditional FA. In a traditional FA, introduction of a single putative establishing operation should primarily evoke responses that have produced the individual consequence in the past. For example, introduction of demands should primarily evoke problem behavior if escape from demands has previously reinforced problem behavior. Whereas if removal of the tangible item is not an establishing operation for problem behavior, then problem behavior would not be evoked during the tangible test condition. Therefore, the nonfunctional, but preferred, stimulus would not be delivered contingent upon problem behavior.

An unavoidable limitation of previous comparisons of SCAs with traditional FAs is that it is not possible to know with surety what the true function of problem behavior was in the participants’ natural environment prior to conducting the analyses. One way to address this limitation is through a translational investigation in which the researchers program particular functions for a novel response which had no history of reinforcement prior to conducting the comparison. The experimenters then know the history of reinforcement and the true function of the target response at the outset of the investigation. In the current investigation, we used this approach to evaluate (a) the extent to which a traditional FA accurately identified the function programmed by the researchers for the target response and (b) whether the traditional FA or SCA induced new functions for the target response after exposure to consequences not previously correlated with the target response.

Method

Participants

Six children diagnosed with ASD who attended a university-based, early intervention program participated in this study. These participants typically complied with therapist instructions and did not display clinically significant levels of destructive behavior (i.e., occurring during more than 25% of waking hours and/or at an intensity that resulted in visible markings). Molly, a 7-year-old female, and Tylor, a 4-year-old male, each communicated using 2- to 3-word phrases. Bobby, a 9-year-old male, Doug, a 4-year-old male, Adam, a 4-year-old male, and Kathy, a 6-year-old female each communicated using multi-word sentences.

Setting and Materials

We conducted sessions at an early intervention clinic in small cubicles (approximately 2.5 m by 1.8 m) or in individual therapy rooms (approximately 3 m by 3 m). Each space contained a small table, chairs, and work or leisure items relevant to the condition.

We identified preferred leisure items based on therapist nomination and a paired-stimulus preference assessment (Fisher, Piazza, Bowman & Amari, 1996; Fisher, et al, 1992). We included these items in certain conditions of the traditional FA and SCA (as specified below). High-preference tangible items included an iPad (Molly, Doug, and Adam), an Angry Birds sticker book (Bobby), coloring materials (Kathy), and puzzles and animal figurines (Tylor). Low-preference tangible items included a dollhouse (Molly and Kathy), a toy treehouse and an Angry Birds stuffed animal (Bobby), books (Doug), an iPad (Tylor), and a soccer ball (Adam). We also identified demand materials based on therapist nomination, which we included in relevant test conditions (as specified below). Demands included receptive-object identification (Molly, Tylor, and Adam), site-word reading (Bobby), answering intraverbal questions (Doug and Kathy), gross-motor imitation (Tylor and Adam), and expressive-object identification (Tylor and Adam). We created two small, rectangular foam cushions (19 cm x 21 cm) covered with colored felt to serve as the target for the surrogate destructive response.

Measurement

Data collectors used laptop computers with a specialized data-collection program (Bullock, Fisher, & Hagopian, 2017) to collect frequency data on the surrogate destructive behavior and actual destructive behavior, which we later converted to rate measures (i.e., responses per minute). The surrogate destructive behavior was defined as the participant’s palm contacting the top of the colored cushion from a distance of 7.6 cm or greater. Destructive behavior included aggression, disruptions, and self-injurious behavior (SIB). Aggression included hitting or kicking the therapist from a distance of 15.2 cm or greater. Disruptions included swiping or throwing work materials and hitting or kicking furniture from a distance of 15.2 cm or greater. Self-injurious behavior included self-hitting from a distance of 7.6 cm or greater, but no instance of SIB were observed.

A second observer collected data from recorded video on at least 34% of all sessions to assess interobserver agreement. The second data collector was blind to the purpose and hypotheses of the study for at least 42% of these observations for each participant with the exception of Adam. For Adam, the primary data collector was blind to the purpose and hypotheses of the study for all sessions, however the secondary data collector was never blind to the purpose and hypotheses of the study. We divided each session into 10-s intervals and recorded an agreement for each interval in which both observers measured the same number of responses (i.e., exact agreement within the interval). We then divided the number of agreement intervals by the total number of intervals of the session and converted the resulting quotient to a percentage. Agreement coefficients for the surrogate destructive behavior averaged 99% or greater for each participant. Agreement coefficients averaged 99.9% for aggression and 99.6% for disruptions across all participants.

Design

We used a multielement design to compare the test and control conditions during the traditional FA and the SCA. We introduced the SCA following the initial traditional FA in accordance with a nonconcurrent, multiple-baseline design across participants. We staggered introduction of the SCA to ensure that various lengths of the traditional FA were evaluated. We used a reversal design (ABCB) to evaluate whether the traditional FA and SCA produced iatrogenic effects (with A = pretraining an operant function, B = traditional FA, and C = SCA). The traditional FA tested for multiple functions in isolation which allows for detection of any newly established functions (e.g., attention function trained; tangible function emerges as indicated by high levels of responding in the tangible condition compared to the control condition). The contingencies in an SCA are combined so it is not possible to determine if the SCA induced any new functions simply based on the SCA data. Therefore, another traditional FA occurred following the SCA to determine whether any new functions of the surrogate target response emerged following exposure to the SCA.

Procedures

Pretraining an operant function.

We quasi-randomly assigned each participant to one of three common social functions (i.e., tangible, attention, escape) such that two participants were assigned to each common social function. We used a progressive-prompt delay to teach the participant to engage in a response (i.e., touching a cushion) that served as the surrogate destructive behavior to access either a tangible item (Bobby and Kathy), adult attention (Tylor and Adam), or escape from demands (Molly and Doug). Sessions consisted of ten 30-s trials. Each trial began with the presentation of the establishing operation (i.e., removing attention or the high-preference tangible item, or presenting demands) until the participant engaged in the response. We used physical guidance to teach the response and progressively delayed (up to 20 s) the presentation of physical guidance to establish independent responding.

Two response options (i.e., two different colored cushions) were present. One response was correlated with extinction and the other with a fixed-ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement. Once the participant independently engaged in the response producing reinforcement for 90% of trials for two consecutive sessions, the contingencies were reversed. Pretraining ended when the participant independently engaged in the response producing reinforcement for 90% of trials for two consecutive sessions following the reversal of contingencies.

During the traditional FA and SCA (described below), we included a single pad (i.e., the most recently reinforced response option). For Doug, we conducted a booster session prior to Session 15 to re-establish the surrogate destructive behavior since a few weeks had elapsed since his prior session. The booster session consisted of 10 trials with faded within-session response prompts progressing from 0 s to 10 s.

Traditional FA.

The traditional FA was designed based on the procedures described by Iwata et al. (1982/1994) with the modifications suggested by Fisher, Piazza, and Chiang (1996). The traditional FA continued for at least three series and until the FA resulted in differentiated responding according to the structured criteria described by Saini, Fisher, and Retzlaff (2018). The traditional FA was extended beyond the number of necessary series for some participants to ensure we evaluated traditional FAs of various lengths. All sessions lasted 5 min. There were no programmed consequences for destructive behavior (i.e., extinction) during the traditional FA. The therapist wore a uniquely colored smock during each condition for all participants except Kathy (due to therapist error).

Attention.

Prior to the attention condition, the therapist provided attention to the child for approximately 30 s. The session began with the therapist stating, “I have some work to do” and beginning to read a magazine (i.e., restricted attention). The therapist provided 20-s access to attention (i.e., interactive play) after each instance of the surrogate destructive behavior. Throughout attention sessions, the participant had continuous access to a low-preference tangible item.

Toy play.

The therapist provided continuous access to attention and a high-preference tangible item in the toy-play condition. No demands were presented and there were no programmed consequences for the surrogate destructive behavior (i.e., extinction).

Escape.

For tasks involving motor behavior, the therapist presented successive vocal, model, and physical prompts until the participant displayed compliance or the surrogate destructive behavior. For demands requiring a vocal response (e.g., reading aloud), the therapist repeat the model prompt until the participant either (a) displayed compliance or (b) engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior. The therapist provided descriptive praise for compliance following the vocal or the first model prompt (e.g., “You’re right, that is the dog!”). The therapist provided a 20-s break from demands by saying, “Okay you don’t have to”, removing any demand materials, and turning away from the participant after each instance of the surrogate destructive behavior.

Tangible.

Prior to the session, the child had access to the preferred tangible item for approximately 30 s. The session began with the therapist saying, “My turn” while simultaneously restricting access to the item. While access was restricted, the therapist interacted with the item (e.g., played games on the iPad) but did not allow the participant to engage with the item or view the screen (iPad only). The therapist provided 20-s access to the preferred item after each instance of the surrogate destructive behavior.

Synthesized Contingency Analysis.

Synthesized contingency analyses described in the extant literature generally develop the test and control conditions based on a combination of caregiver report and observation of the individual (e.g., Hanley et al., 2014). These children did not engage in destructive behavior according to caregiver report and learned a new response with a controlled history. Thus, the typical applied procedures could not be used in this translational preparation (i.e., caregiver report and observation could not be used to construct the synthesized test condition). Therefore, we examined published examples of SCAs in order to create a representative standard synthesized test condition. Jessel, Hanley, & Ghaemmaghami (2016) reported on 30 SCAs and found 23 of the 30 analyses included both a positive- and negative-reinforcement contingency. Additionally, at least 16 of the 30 analyses included multiple positive reinforcers, indicating the majority of SCAs included all three common social functions of destructive behavior (i.e., escape, access to attention, and access to tangibles). Thus, all three common social functions were included in the synthesized test condition to represent a common form of published SCA.

During the SCA, all sessions lasted 5 min and included no programmed consequence for destructive behavior (i.e., extinction). The therapist wore a uniquely colored smock for each condition for all participants except Kathy (due to therapist error).

Control.

The therapist provided continuous access to attention and a high-preference item. We programmed no consequence for the surrogate destructive behavior (i.e., extinction).

Test.

Prior to the SCA test condition, the therapist provided attention and access to the high-preference item for approximately 30 s. The session began with therapist simultaneously removing access to the preferred item, terminating the attention delivery, and presenting demands using the same procedures described for the escape condition of the traditional FA. The therapist provided a 20-s break from demands by saying, “Okay you don’t have to” and removing any demand materials after each instance of the surrogate destructive behavior. During the escape interval, the therapist delivered continuous attention and access to the preferred item.

Results

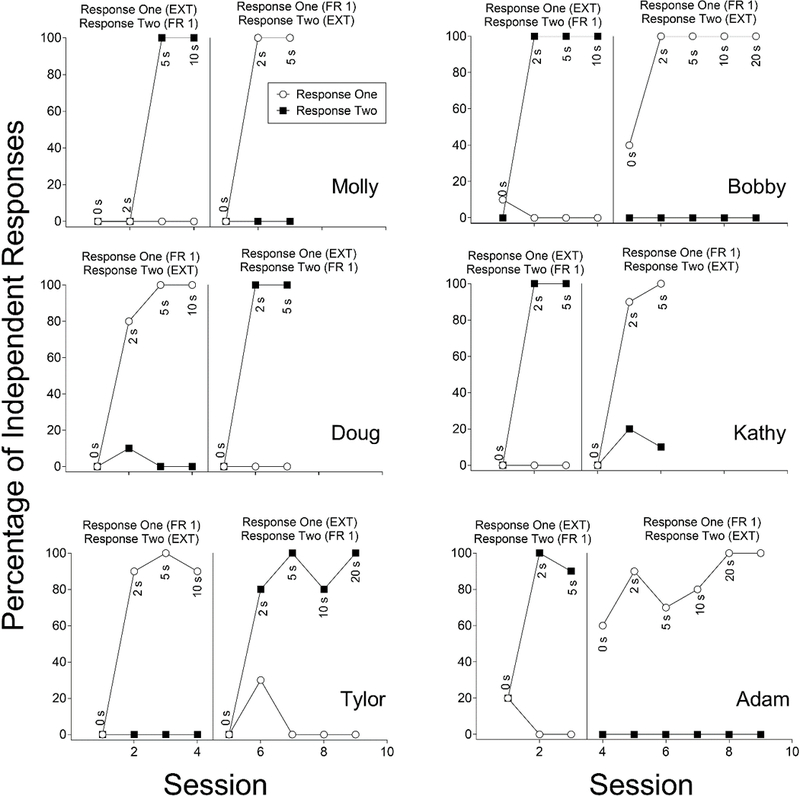

Figure 1 shows the percentage of independent responses for each response option during pretraining sessions. Each participant engaged in the response associated with reinforcement almost exclusively. All participants completed the pretraining phase in less than 10 sessions.

Figure 1.

Percentage of independent responses for Response One (open circles) and Response Two (closed squares) for all participants during pretraining an operant function. The data labels indicate the progressive prompt delay to physical guidance. Note for Adam and Bobby independent responses sometimes occurred during the 0-s prompt delay due to the participant engaging in the response as the therapist was introducing the establishing operation. EXT = extinction, FR 1 = fixed ratio 1

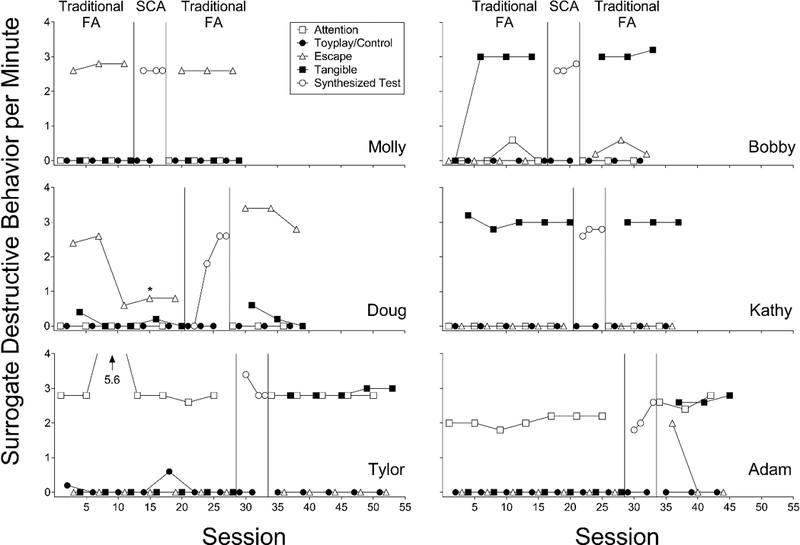

Figure 2 shows the surrogate destructive behaviors per minute across sessions for each participant. Molly learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to escape demands. During the initial traditional FA, Molly reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during the escape condition and did not engage in the response during any other condition. During the SCA, Molly reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition. Following the SCA, the traditional FA was reintroduced to determine whether any new functions emerged following exposure to the SCA. Molly again emitted the surrogate destructive behavior only during the escape condition. These results identified escape as the only function of the surrogate destruction behavior according to the structured criteria from Saini et al. (2018). The same structured criteria indicated that the SCA test condition differed from the control condition (i.e., escape, tangible, and attention combined to reinforce the surrogate destructive behavior). Thus, for Molly we observed no iatrogenic effects of the traditional FA or SCA in the form of induction of novel functions of the target response.

Figure 2.

Surrogate destructive behavior per minute across sessions for each participant during the initial functional analysis (FA), the synthesized contingency analysis (SCA), and the second FA. A booster session occurred prior to the session marked with an asterisk for Doug.

Bobby learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to access the high-preference item. During the initial traditional FA, Bobby reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during the tangible condition and rarely engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior in any other condition. During the SCA, Bobby reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition. During the second traditional FA, Bobby engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior most often during the tangible condition. Bobby also reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during the escape condition, albeit at lower rates than during the tangible condition. The structured criteria from Saini et al. (2018) identified tangible reinforcement as the only function of the surrogate destructive behavior in the first traditional FA. These structured criteria identified both tangible and escape as functions of the surrogate destructive behavior during the second traditional FA, suggesting induction of one novel function (i.e., escape) following exposure to the SCA. According to the structured criteria the SCA test condition differed from the control condition (i.e., escape, tangible, and attention combined to reinforce the surrogate destructive behavior). For Bobby, the SCA appears to have produced an iatrogenic effect in the form of induction of a new function (i.e., escape) not taught during the pretraining and not observed during the initial traditional FA.

Doug learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to escape demands. During the initial traditional FA, Doug reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during the escape condition, never emitted the response in the attention condition, and rarely (i.e., 3 instances across 5 sessions) emitted the response during the tangible condition. The structured criteria indicated escape as the function of the response during the initial traditional FA. During the SCA, Doug engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition, and the structured criteria indicated the SCA test condition differed from the control. During the second traditional FA, Doug reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during the escape condition, and the structured criteria identified an escape function of the response. During the second traditional FA, Doug engaged in higher rates of the surrogate destructive behavior during the escape condition compared to the initial traditional FA. This increase in rate reflects an increase in response efficiency (i.e., during the second FA Doug reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior almost immediately following the initial instruction), as well as an increase in responding during the break interval during Sessions 30 and 34 (separated data not shown). Thus, for Doug we observed no significant iatrogenic effects in the form of induction of novel functions of the target response for either the traditional FA or the SCA.

Kathy learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to access the high-preference item. During the initial FA, Kathy reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during the tangible condition and did not engage in the surrogate destructive behavior during any other condition. During the SCA, Kathy reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition. When we reintroduced the FA, Kathy again only engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during the tangible condition. The structured criteria identified a tangible function during both traditional FAs and indicated the SCA test condition differed from the control condition (i.e., escape, tangible, and attention combined to reinforce the surrogate destructive behavior). Thus, for Kathy we observed no iatrogenic effects of either the traditional FA or the SCA in the form of induction of novel functions of the target response.

Tylor learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to access attention from the therapist. During the initial traditional FA, Tylor reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during the attention condition and only engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior on three occasions in the toy-play condition. During the SCA, Tylor reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition. During the second traditional FA, Tylor reliably engaged in surrogate destructive behavior during both the attention and tangible conditions. When we applied the structured criteria to Tylor’s first traditional FA, the criteria identified attention as the only function of the surrogate destructive behavior. When we applied the same structured criteria to Tylor’s second traditional FA, the criteria identified both attention and tangible reinforcement as functions of the surrogate destructive behavior, suggesting induction of one novel function (i.e., tangible) after exposure to the SCA. The same structured criteria indicated that the SCA test condition differed from the control condition (i.e., escape, tangible, and attention combined to reinforce the surrogate destructive behavior). Thus, the results for Tylor suggest that exposure to the SCA produced an iatrogenic effect in the form of induction of a new function (i.e., tangible) not taught during the pretraining and not observed during the initial traditional FA.

Adam learned to engage in the surrogate destructive behavior to access attention from the therapist. During the initial traditional FA, Adam reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during the attention condition and never engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior during any other condition. During the SCA, Adam reliably engaged in the surrogate destructive behavior only during the test condition. During the second traditional FA, Adam emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during the initial escape session, and reliably emitted the surrogate destructive behavior during both the attention and tangible conditions. The structure criteria indicated attention as the function of the response during the initial traditional FA. The same criteria identified the SCA test condition differed from the control condition, and indicated attention and tangible as the function of the response during the second traditional FA. Thus, the results for Adam suggest that exposure to the SCA produced an iatrogenic effect in the form of induction of a new function (i.e., tangible) not taught during the pretraining and not observed during the initial FA.

In addition to measuring the frequency of the surrogate destructive behavior, we also measured the frequency of each participant’s (actual) destructive behavior (data available upon request). Molly, Doug, and Kathy engaged in zero instances of destructive behavior during the study, consistent with parental report. Bobby rarely engaged in destructive behavior during the initial traditional FA and never engaged in destructive behavior during the SCA. However, Bobby began to engage in increasing rates of destructive behavior during the escape condition of the second traditional FA, which resulted in us terminating Bobby’s participation in the study and initiating clinical treatment of his destructive behavior. Tylor rarely engaged in destructive behavior during the initial FA and never engaged in destructive behavior during the SCA. However, Tylor reliably engaged in destructive behavior during the escape condition of the second FA, despite never contacting a break for the surrogate destructive behavior or destructive behavior in the escape condition of either the first or the second traditional FA. Adam engaged in variable levels of destructive behavior throughout the initial and second FA. The majority of instances of destructive behavior were disruptions (i.e., kicking the wall) and occurred in escape sessions.

Discussion

In this translational investigation, we trained an escape (n = 2), an attention (n = 2), and a tangible (n = 2) function for a surrogate destructive behavior in six children with ASD, and then evaluated this preprogrammed response using a traditional FA and an SCA. The initial traditional FA identified the specific function of the surrogate destructive behavior in all six cases, and the initial traditional FA did not show iatrogenic effects in the form of induction of new functions. These results provide evidence for the validity of the traditional FA. By contrast, after exposing the surrogate destructive behavior to an SCA, three of the six participants showed an iatrogenic effect in the form of induction of a new function of the surrogate destructive behavior during the second traditional FA.

The purpose of this translational investigation was to evaluate the potential for iatrogenic effects during traditional FA and SCAs. We selected a translational preparation to ensure that the initial function of the target response was known, because without a known function of the target response, the presence or absence of iatrogenic effects could not be obtained with certainty. Although useful for this purpose, the translational preparation also means the external validity of the findings remains untested. We took care to arrange our translational preparation to approximate traditional FAs typically conducted within the clinic settings we have experienced. However, the use of a standardized SCA test and control condition does not mirror the majority of published IISCAs, which are individualized to a client’s learning history based on caregiver report and observation. Future research is needed to determine the degree to which the findings obtained from this translational study are similar to outcomes obtained during applied analyses with the full IISCA procedure.

Two of the three participants who showed an iatrogenic effect following exposure to the SCA showed induction of a tangible function. Previous investigations have produced parallel results, except in previous research a tangible function emerged during a traditional FA. For example, Rooker et al. (2011) showed that when they applied the contingencies of a traditional FA to a novel response, five of six participants showed greater sensitivity to tangible reinforcement than to the other programmed contingencies (Study 1). Similarly, these investigators showed that when they superimposed tangible contingencies identified via a preference assessment on stereotypy maintained by automatic reinforcement, new, tangible functions emerged for all three participants (Study 2). Shirley et al. (1999) observed similar effects when hand mouthing maintained by automatic reinforcement also produced a highly preferred tangible.

The same operant mechanism may be responsible for the induction of new functions observed in Study 2 of Rooker et al. (2011), Shirley et al. (1999), and the current investigation. In each case a preexisting contingency maintained the target response (i.e., automatic reinforcement in Rooker et al. and Shirley et al., a pretrained social function in the current investigation). Next, the investigators combined that preexisting reinforcement contingency with one or more additional preferred contingencies (e.g., adding a tangible consequence to automatic reinforcement, adding escape and tangible consequences to attention during the SCA). We hypothesize that adding a nonfunctional, but preferred consequence, to a preexisting reinforcement contingency that maintains high levels of the target response ensures the target response will contact the new, preferred contingency. These multiple response-reinforcer contacts then have the potential to induce a new function of the target response.

If this hypothesis is correct, the traditional FA may be most susceptible to iatrogenic effects in the form of the induction of new functions when automatic reinforcement maintains the target response and the analysis exposes the response to additional preferred contingencies. That is, the only time a traditional FA should combine two or more putative reinforcement contingencies in a single test condition is when automatic reinforcement maintains the target response (e.g., behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement occurs in the tangible test condition and the therapist then provides access to a preferred item following that behavior). By contrast, SCAs may be susceptible to iatrogenic effects in the form of a new function of destructive behavior whenever any single reinforcement contingency maintains the target response and the analysis exposes the response to one or more additional putative reinforcement contingencies (i.e., the synthesized contingency). Although there is risk of an iatrogenic effect with an SCA, we observed iatrogenic effects only with a subset of participants. Future research should examine the conditions under which an iatrogenic effect is most likely to occur during an actual SCA conducted under clinically relevant conditions rather than in a translational preparation.

A potential remedy for the risk of iatrogenic effects hypothesized above for the traditional FA is to conduct a screen for automatic reinforcement using the procedures described by Querim et al. (2013). This screen rules in or out automatic reinforcement through the persistence or extinction of problem behavior during repeated alone or ignore sessions. If the screen identifies problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement through persistence of responding, the behavior analyst could proceed to treatment of that automatic function rather than exposing the response to additional contingencies in a full traditional FA. If the screen rules out problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement through extinction of the response, the behavior analyst could proceed to a traditional FA to test for social positive and negative reinforcement contingencies (attention, escape, and tangible, if indicated). By following this model, the behavior analyst may minimize the risk of iatrogenic effects during traditional FA.

The risk for an iatrogenic effect following an SCA may be increased when the target behavior is maintained by a single contingency (e.g., escape), but multiple contingencies are included in the SCA test condition (e.g., escape to tangible). It may be that constructing SCAs based on information obtained from a client’s caregiver and direct observation decreases the potential risk of iatrogenic effects of SCAs because the IISCA may be less likely to include nonfunctional contingencies than the standard SCA used in this study. Slaton and Hanley (2018) reviewed synthesis during FA and found that over 90% of published SCAs included escape to some positive reinforcer and that 25% of published SCAs included escape to attention and preferred items. Greer et al. (conditionally accepted) found that when the informed test condition was based on caregiver interview and/or a structured observation, 50% (i.e., 6 out of 12 cases) of informed test conditions were identical to a standard test condition which included escape to attention and preferred items. As Slaton and Hanley pointed out, most published IISCAs did not include a comparison to traditional FA, and therefore the necessity of synthesis remains unknown in many cases. However, these findings suggest that often times in applied settings the interview-informed test condition is similar or equivalent to the standard SCA test condition used in our study. Future research using procedures similar to Thompson and Iwata (2007) is needed to determine how often IISCAs include nonfunctional or unnecessary contingencies. Additionally, further research is needed to determine if the risk of iatrogenic effects are mitigated by ensuring the SCA is developed using caregiver report and observation.

The current investigation taught a single, social function of the target response for each participant that represents a subset of behavior referred for assessment and treatment in clinical settings (comprehensive reviews suggests that control by a single contingency occurs in 81% to 85% of cases; Beavers et al., 2013; Hanley et al., 2003). Thus, future research also should test for iatrogenic effects during FA and SCA after training the response using synthesized contingencies (e.g., escape to tangible), multiple isolated contingencies (e.g., training an escape function as well as an attention function for the same participant), and automatic reinforcement to better approximate clinical practice. Continued investigation into the benefits and potential risks associated with all types of functional-analysis procedures is crucial to ensure that clinicians are making informed decisions regarding when and how to use each type of analysis.

Acknowledgments

Grants 5R01HD079113, 5R01HD083214, and 1R01HD093734 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provided partial support for this research. This study was conducted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE. Jessica A. Akers is now at Baylor University.

References

- Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Handen B, Arnold LE, Johnson C, … & Sukhodolsky DD (2009). Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 1143–1154. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bfd669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavers GA, Iwata BA, & Lerman DC (2013). Thirty years of research on the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 1–21. doi: 10.1002/jaba.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz AM, & Fisher WW (2011). Functional analysis: History and methods In Fisher WW, Piazza CC, & Roane HS (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Akers JS, Greer BD, Fisher WW, & Retzlaff BJ (2018). Systematic changes in preference for schedule-thinning arrangements as a function of relative reinforcement density. Behavior Modification, 42, 472–497. doi: 10.1177/0145445517742883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock CE, Fisher WW, & Hagopian LP (2017). Description and validation of a computerized behavioral data program: “BDataPro.” The Behavior Analyst, 40, 275–285. doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0079-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centorrino F, Goren JL, Hennen J, Salvatore P, Kelleher JP, & Baldessarini RJ (2004). Multiple versus single antipsychotic agents for hospitalized psychiatric patients: case-control study of risks versus benefits. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 700–706. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, DeLeon IG, Rodriguez‐Catter V, & Keeney KM (2004). Enhancing the effects of extinction on attention‐maintained behavior through noncontingent delivery of attention or stimuli identified via a competing stimulus assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 171–184. 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Greer BD, Romani PW, Zangrillo AN, Owen TM (2016). Comparisons of synthesized and individual reinforcement contingencies during functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49, 596–616. doi: 10.1002/jaba.314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, & Amari A (1996). Integrating caregiver report with systematic choice assessment to enhance reinforcer identification. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 101, 15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, & Slevin I (1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, & Chiang CL (1996). Effects of equal and unequal reinforcer duration during functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 117–120. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami M, Hanley GP, Jin SC, & Vanselow NR (2016). Affirming control by multiple reinforcers via progressive treatment analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 31, 70–86. doi: 10.1002/bin.1425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goin-Kochel RP, Myers BJ, & Mackintosh VH (2007). Parental reports on the use of treatments and therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer BD, Fisher WW, Saini V, Owen TM, Jones JK (2016). Functional communication training during reinforcement schedule thinning: An analysis of 25 applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49, 105–121. doi: 10.1002/jaba.265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer BD, Mitteer DR, Briggs AM, Fisher WW, & Sodawasser AJ (conditionally accepted). On the accuracy of synthesized contingency analysis for determining behavioral function and the utility of the assessments informing synthesis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Wilson DM, & Wilder DA (2001). Assessment and treatment of problem behavior maintained by escape from attention and access to tangible items. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34, 229–232. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP (2012). Functional assessment of problem behavior: Dispelling myths, overcoming implementation obstacles, and developing new lore. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5, 54–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03391818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, & McCord BE (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Jin CS, Vanselow NR, & Hanratty LA (2014). Producing meaningful improvements in problem behavior of children with autism via synthesized analyses and treatments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47, 1636. doi: 10.1002/jaba.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, & Richmond GS (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197–209. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982). doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA & Dozier CL (2008). Clinical application of functional analysis methodology. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1, 3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03391714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessel J, Hanley GP, & Ghaemmaghami M (2016). Interview-informed synthesized contingency analyses: Thirty replications and reanalysis. Journal of Applied Behavior, 49, 576–595. doi: 10.1002/jaba.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessel J, Hausman NL, Schmidt JD, Darnell LC, & Kahng S (2014). The development of false-positive outcomes during functional analyses of problem behavior. Behavioral Interventions, 29, 50–61. doi: 10.1002/bin.1375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jessel J, Ingvarsson ET, Metras R, Kirk H, & Whipple R (2018). Achieving socially significant reductions in problem behavior following the interview-informed synthesized contingency analysis: A summary of 25 outpatient applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51, 130–157. doi: 10.1002/jaba.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRue RH, Stewart V, Piazza CC, Volkert VM, Patel MR, & Zeleny J (2011). Escape as reinforcement and escape extinction in the treatment of feeding problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 719–735. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC & Iwata BA (1993). Descriptive and experimental analyses of variables maintaining self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26, 293–319. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, & Polsky DE (2008). Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 121, e441–e448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver AC, Pratt LA, & Normand MP (2015). A survey of functional behavior assessment methods used by behavior analysts in practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48, 817–829. doi: 10.1002/jaba.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald DP & Sonenklar NA (2007). Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 17, 348–355. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.17303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querim AC, Iwata BA, Roscoe EM, Schlichenmeyer KJ, Ortega JV, & Hurl KE (2013). Functional analysis screening for problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 47–60. doi: 10.1002/jaba.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roane HS, Fisher WW, & Carr JE (2016). Applied behavior analysis as treatment for autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooker GW, Iwata BA, Harper JM, Fahmie TA, & Camp EM (2011). False-positive tangible outcomes of functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 737–745. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE, Mandell DS, Farmer JE, Law JK, Marvin AR, & Law PA (2010). Psychotropic medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders enrolled in a national registry, 2007–2008. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 342–351. doi: 10.1007/s10801-009-0878-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V, Fisher WW, & Retzlaff BJ (2018). Predictive validity and efficiency of ongoing visual-inspection criteria for interpreting functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51, 303–320. doi: 10.1002/jaba.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago JL, Hanley GP, Moore K, & Jin CS (2016). The generality of interview-informed functional analyses: Systematic replications in school and home. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 797–811. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2617-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaton JD & Hanley GP (2018). Nature and scope of synthesis in functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51, 943–973. doi: 10.1002/jaba.498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaton JD, Hanley GP, & Raftery KJ (2017). Interview‐informed functional analyses: A comparison of synthesized and isolated components. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50, 252–277. doi: 10.1002/jaba.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MJ, Iwata BA, & Kahng S (1999). False-positive maintenance of self-injurious behavior by access to tangible reinforcers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32, 201–204. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, & Iwata BA (2007). A comparison of outcomes from descriptive and functional analyses of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 333–338. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.56-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarcone JR, Iwata BA, Vollmer TR, Jagtiani S, Smith RG, & Mazaleski JL (1993). Extinction of self‐injurious escape behavior with and without instructional fading. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26, 353–360. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]